Abstract

Animal development relies on a sequence of specific stages that allow the formation of adult structures with a determined size. In general, juvenile stages are dedicated mainly to growth, whereas last stages are devoted predominantly to the maturation of adult structures. In holometabolous insects, metamorphosis marks the end of the growth period as the animals stops feeding and initiate the final differentiation of the tissues. This transition is controlled by the steroid hormone ecdysone produced in the prothoracic gland. In Drosophila melanogaster different signals have been shown to regulate the production of ecdysone, such as PTTH/Torso, TGFß and Egfr signaling. However, to which extent the roles of these signals are conserved remains unknown. Here, we study the role of Egfr signaling in post-embryonic development of the basal holometabolous beetle Tribolium castaneum. We show that Tc-Egfr and Tc-pointed are required to induced a proper larval-pupal transition through the control of the expression of ecdysone biosynthetic genes. Furthermore, we identified an additional Tc-Egfr ligand in the Tribolium genome, the neuregulin-like protein Tc-Vein (Tc-Vn), which contributes to induce larval-pupal transition together with Tc-Spitz (Tc-Spi). Interestingly, we found that in addition to the redundant role in the control of pupa formation, each ligand possesses different functions in organ morphogenesis. Whereas Tc-Spi acts as the main ligand in urogomphi and gin traps, Tc-Vn is required in wings and elytra. Altogether, our findings show that in Tribolium, post-embryonic Tc-Egfr signaling activation depends on the presence of two ligands and that its role in metamorphic transition is conserved in holometabolous insects.

Subject terms: Developmental biology, Morphogenesis, Biological metamorphosis

Introduction

Animal development consists of a number of stage-specific transitions that allows the growth of the organism and the proper morphogenesis of adult structures. Whereas growth mostly takes place during juvenile stages, final adult differentiation and sexual maturity occurs mainly by tissue remodeling. Thus, the transition from juvenile to adult stage determines the final size of the animal. Examples of this particular transition are puberty in humans and metamorphosis in insects. Despite its importance, however, the precise mechanisms underlying the regulation of this developmental transition are far from being clearly understood.

Holometabolous insects are a paradigm for the study of the precise control of the transition between the immature larva and the adult, which happens through a transitional metamorphic stage, the pupa. In these insects, a pulse of the steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E) at the end of the larval period triggers the onset of metamorphosis1,2. Biosynthesis of ecdysone, the precursor of 20E, takes place in a specialized organ called the prothoracic gland (PG) and is controlled by the restricted expression of several biosynthetic enzymes encoding genes collectively referred to as the Halloween genes. These include the Rieske-domain protein neverland (nvd)3,4, the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase shroud (sro)5 and the P450 enzymes spook (spo), spookier (spok), phantom (phm), disembodied (dib) and shadow (sad)6–11. Work carried out in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster revealed that the proper function of the PG at the metamorphic transition, including the timely expression of the Halloween genes, involves the integrated activity of different signaling pathways such as TGFß/activin12, Insulin receptor (InR)13–16, and PTTH/Torso pathways17–19. Whereas insulin and PTTH/Torso pathways promote the up-regulation of the Halloween genes at the appropriate developmental time to trigger metamorphosis2, TGFß/activin signaling regulates insulin and PTTH/Torso pathways in the PG by controlling the expression of their respective receptors12. In addition to these pathways, we have recently shown that the activation of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (Egfr) signaling pathway in PG cells is also critical for ecdysone production at the metamorphic transition20. Thus, Egfr pathway activation controls Halloween gene expression and ecdysone vesicle secretion during the last larval stage. Importantly, it has been shown that the control of the metamorphic transition by TGFß/activin, Insulin receptor (InR), and PTTH/Torso pathways is conserved in other non-dipteran holometabolous insects21–28. However, the grade of conservation of the Egfr signaling pathway in this process has not been well established.

In Drosophila, Egfr is activated by four ligands with a predicted Egf-like motif: the TGF-like proteins Gurken (Grk), Spitz (Spi) and Keren (krn), and the neuregulin-like protein Vein (Vn). The specific expression and activity of these ligands in different tissues appear to be responsible for different levels of EGF signaling activation in particular developmental contexts29,30. For example, Krn acts redundantly with Spi in the embryo, during eye development and in adult gut homeostasis31–33, whereas Grk is specific of the germline, where it acts to establish egg polarity34,35. In contrast, Vn acts as the main ligand in the wing, in muscle attachment sites, during the air sac primordium development and in the patterning of the distal leg region36–40. Once Egfr is activated by any of its ligands, the signal is relayed through the sequential activation of the MAPK/ERK kinase pathway to the nucleus, where is finally mediated by the transcription factor Pointed (Pnt)41,42.

In the present work, we aim to study the role of Egfr signaling pathway in the control of the metamorphic transition in the more basal holometabolous insect, the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum, which diverged from Drosophila ∼ 250 million years ago. Despite the early divergence between both species, the role of this pathway in the control of several developmental processes has been revealed to be conserved. For example, it induces the encapsulation of the oocyte by the somatic follicle cell layer and establishes the polarity of the egg chambers and the D–V axis of the embryo during oogenesis43. It also controls the formation and patterning of the legs and the proper development of the abdomen and Malpighian tubules during embryogenesis43–45, and regulates distal development of most appendages such as leg, antenna, maxilla and labium, and promotes axis elongation of the mandibles46–48. Despite this functional conservation, a remarkable difference between Drosophila and Tribolium is found in the number of Egfr ligands identified, for only a single TGF-EGF ligand, Tc-Spi, has been found in the beetle44.

In here, we confirm that Tc-Egfr signaling is required for a normal ecdysone-dependent transition from larval to pupal stages in Tribolium. We found that inactivation of Tc-Egfr signaling in the last larval stage results in the arrest of larval development at the larval-pupal transition, with arrested larvae presenting reduced levels of the Halloween gene Tc-phm, as well as of the ecdysone-dependent transcription factors Tc-Hr3, Tc-E75 and Tc-Broad Complex (Tc-Br-C). Importantly, we provided evidence of the existence of an additional Tc-Egfr ligand in Tribolium, the neuregulin-like protein Tc-Vein (Tc-Vn). We show that Tc-Vn and Tc-Spi act redundantly in the control of larval-pupal transition, while functioning separately during pupal morphogenesis. Taken together, our results strongly suggest that Egfr signaling pathway plays a conserved central role in the control of the ecdysone-dependent larval-pupal transition and during the morphogenesis of the pupa in holometabolous insects.

Results

Egfr signaling is required for larval-pupal transition in Tribolium

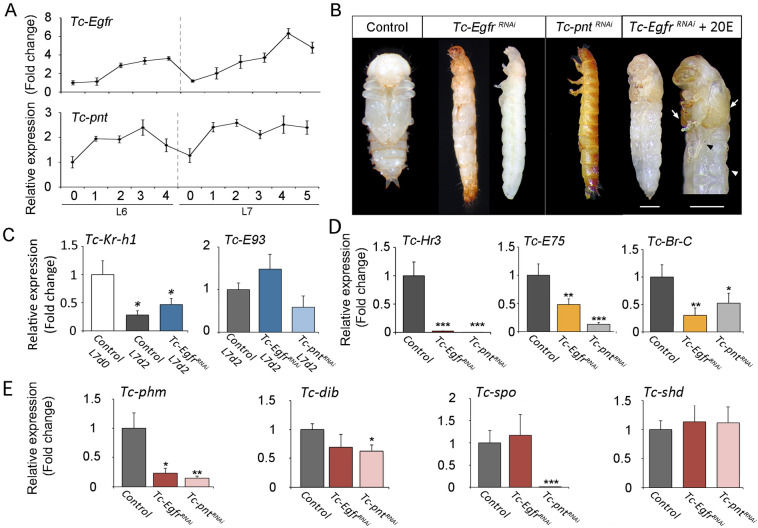

As a first step towards the characterization of Egfr signaling in post-embryonic Tribolium, we measured mRNA levels of Tc-Egfr and Tc-pnt by RT-qPCR in staged penultimate (L6) and last (L7) instar larvae. Expression of Tc-Egfr and Tc-pnt was low at the onset of both instars, and then steadily increased to reach the maximal level at the final part of each instar, which suggests a role of Egfr signaling during stage transitions (Fig. 1A). To examine this possibility, we analyzed the functions of both factors depleting Tc-Egfr and Tc-pnt by injecting dsRNAs for each transcript in L6 instar larvae (Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-pntRNAi animals). Specimens injected with dsMock were used as negative controls (Control animals). All Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-pntRNAi L6 larvae molted to normal L7 larvae but then failed to pupate at the ensuing molt, as did Control larvae. Instead, they arrested development during the larval-pupal transition (Fig. 1B and S1 Table). Remarkably, removing the larval cuticle of these animals revealed a larval-like morphology (Fig. 1B and S1 Table). To discard a possible effect in the nature of the affected transition in the arrested animals, from larva to pupa, we analyzed the expression levels of the juvenile hormone transducer Kruppel homolog 1 Tc-Kr-h149 and the metamorphosis-triggering factor Tc-E9350. As Fig. 1C shows, arrested Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-pntRNAi animals showed the proper downregulation of Tc-Kr-h1 and upregulation of Tc-E93 that is characteristic of larvae being in the last larval instar, thus indicating that lack of Egfr signaling did not affect the nature of the larval-pupal transition (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Egfr signalling controls larval-pupal transition in Tribolium. (A) Tc-Egfr and Tc-pnt mRNA levels measured by qRT-PCR in penultimate (L6) and ultimate (L7) instar larvae. Transcript abundance values are normalized against the Tc-Rpl32 transcript. Fold changes are relative to the expression of Tc-Egfr and Tc-pnt in day 0 of L6 larvae, arbitrarily set to 1. Error bars indicate the SEM (n = 5). (B) L6 larvae were injected with dsMock (Control) or with dsTc-Egfr (Tc-EgfrRNAi), and dsTc-pnt (Tc-pntRNAi) and left until the ensuing molts. Ventral views of a Control pupa, Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-pntRNAi larvae with and without cuticle, arrested at the larval-pupal transition and Tc-EgfrRNAi larvae after injection of 20E. Scale bar represents 0.5 mm. (C–E) Transcript levels of Tc-Kr-h1 and Tc-E93 at the indicated stages (C), and Tc-Hr3, Tc-E75 and TcBr-C (D) and biosynthetic ecdysone genes Tc-phm, Tc-dib, Tc-spok and Tc-shd (E) measured by qRT-PCR in 5-day-old L7 Control, Tc-EgfrRNAi, and Tc-pntRNAi larvae. Transcript abundance values were normalized against the Tc-Rpl32 transcript. Average values of three independent datasets are shown with standard errors (n = 6). Asterisks indicate differences statistically significant at *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.001 (t-test).

Since Tc-Egfr and Tc-pnt were also expressed in L6, we studied whether Egfr signaling was also required in earlier larval-larval transitions. To this aim, we injected dsRNA of Tc-Egfr in antepenultimate L5 larvae. Under these conditions, all L5-Tc-EgfrRNAi larvae developed normally and underwent two successive molts until reaching L7 (S2 Table), when larvae arrested development before pupation confirming that Egfr signaling is only required for the last larval transition.

Since the larval-pupal transition is ecdysone-dependent, the phenotype presented by Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-pntRNAi larvae is consistent with an ecdysone-signaling deficiency. To assess this hypothesis, we injected the active form 20E into Egfr-depleted larvae. Ectopic addition of 20E partially rescued the developmental arrest phenotype as animals underwent pupation although showing morphological defects in elytra, wings and legs, probably due to the pleiotropic effect of the Egfr signaling (Fig. 1B and S1 Table). To confirm the action of Egfr pathway on ecdysone biosynthesis, we measured mRNA expression levels of the direct ecdysone-dependent genes Tc-Hr3, Tc-E75 and Tc-Br-C in late L7 larvae, which are commonly used as proxies for ecdysone levels17,51,52. As Fig. 1D shows, Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-pntRNAi larvae presented significantly reduced expression levels of these genes compared to Controls. Consistently, the expression of the Halloween gene phm was also decreased in Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-pntRNAi larvae (Fig. 1E). However, the expression of three other Halloween genes, Tc-dib, Tc-spo and Tc-shd, was not affected by the absence of Tc-Egfr (Fig. 1E), indicating that the downregulation of Tc-phm is specific and not due to a general transcriptional effect. Interestingly, in addition to the transcriptional regulation of Tc-phm, the gene expression levels of Tc-dib and Tc-spo were also downregulated in Tc-pntRNAi larvae compared to Controls (Fig. 1E), indicating a stronger inactivation of Tc-Egfr signalling upon depletion of this transcription factor. Taken together, these results indicate that Tc-Egfr signaling is specifically required for a proper ecdysone-dependent larval-pupal transition in Tribolium.

Identification of the Tc-Egfr ligand Tc-Vein in Tribolium

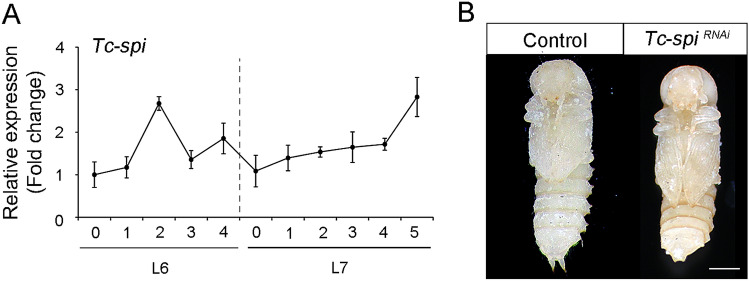

The next question was to determine which EGF ligand was responsible for the activation of the Tc-Egfr pathway during the larval-pupal transition. As stated before, the TGFα-like protein Tc-Spi is the only Tc-Egfr ligand identified in Tribolium44. Expression analysis of Tc-spi during the last two larval instars revealed that it is expressed in a similar pattern to Tc-Egfr (Fig. 2A), which suggests that Tc-Spi might act as the Tc-Egfr ligand during the transition. We studied this possibility by injecting dsTc-spi into L6 larvae (Tc-spiRNAi animals). Unexpectedly, and in contrast to Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-pntRNAi larvae, all L7-Tc-spiRNAi larvae molted to L7 and then to pupa on a normal schedule (Fig. 2B and S3 Table), suggesting the occurrence of different Tc-Egfr ligands during the post-embryonic development of Tribolium.

Figure 2.

Tc-Spi is not the sole ligand of Tc-Egfr signaling during larval-pupal transition in Tribolium. (A) Tc-spi mRNA levels measured by qRT-PCR in penultimate (L6) and ultimate (L7) instar larvae. Transcript abundance values are normalized against the Tc-Rpl32 transcript. Fold changes are relative to the expression of Tc-Egfr and Tc-pnt in day 0 of L6 larvae, arbitrarily set to 1. Error bars indicate the SEM (n = 5). (B) L6 larvae were injected with dsMock (Control) or with dsTc-spi (Tc-spiRNAi) and left until the ensuing molts. Ventral views of Control and Tc-spiRNAi pupae. Scale bar represents 0.5 mm.

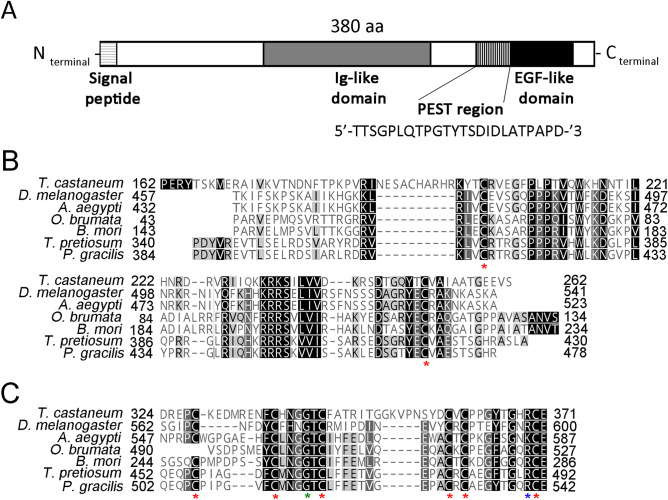

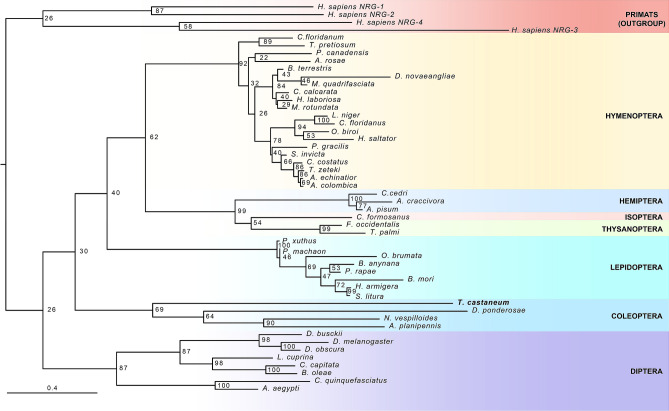

In Drosophila four different Egf ligands have been identified: Dm-Grk, Dm-Ker and Dm-Spi are TGF-like proteins, whereas Dm-Vn belongs to the neuregulin-like family29. Tc-Spi is highly similar to the three Drosophila genes Dm-Grk, Dm-Spi and Dm-Ker being the only TGF-like ligand that activates Egfr in Tribolium31,53. In contrast, no neuregulin-like protein has been identified in Tribolium. To investigate the presence of a neuregulin-like Egf ligand, we performed a detailed Tblastn search in the beetle genome database with the Dm-Vn sequence of Drosophila. This search revealed the presence of a Tc-Vn orthologue in Tribolium. The predicted Tc-Vn protein has 380 amino acids and presents conserved EGF-like and neuregulin Ig-like domains as well as a PEST region, all of which are characteristic of Vn proteins54 (Fig. 3A and S1 Fig). Additionally, Tc-Vn contains a hydrophobic region at the amino terminus that is typical of a signal sequence, a feature that is consistent with Tc-Vn being a secreted protein. The neuregulin Ig-like domain consists of 100 amino acids and presents the two invariant cysteine residues typical of the domain (Fig. 3B and S1 Fig). The EGF-like domain is 47 amino acids long and presents the six invariant cysteines and highly conserved glycine and arginine residues characteristic of the motif (Fig. 3C and S1 Fig. 55,56). Finally, Tc-Vn contains a 24 amino acid long PEST region, characteristic of proteins with short half-lives, that localizes between the EGF-like and neuregulin Ig-like domains (Fig. 3A and S1 Fig). Phylogenetic analysis of Vn protein sequences showed that Tc-Vn grouped with others coleopteran sequences, confirming that Tc-Vn belongs to neuregulin Ig-like family (Fig. 4 and S4 Table). Altogether, these data confirmed that Tribolium possesses two Egf ligands, the TGF-like Spitz and the neuregulin-like Vein.

Figure 3.

The structure of Tribolium Tc-Vn protein. (A) Predicted amino acid sequence of Tc-Vn. The signal peptide is shown in horizontal striped box. Two highly conserved protein domains Ig-like (grey box) and EGFR-like (black box) are indicated. The PEST region is represented by vertical striped box. (B) Protein alignment of Ig-like domain and (C) Egfr-like domain. Asterisks in red indicate the invariant highly conserved cysteines, in green the conserved Glycine and in blue the conserved Arginine from IG-like and Egfr-like domains.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of Vn proteins. Phylogenetic tree based in Vn protein sequences from 44 different insect taxa including the Tc-Vn sequence of Tribolium described in this study. Four primate Hs-Vn sequences are used as outgroup. Tribolium is shown in bold. The different insect orders are indicated in right part of the phylogenetic tree.

Tc-Vn and Tc-Spi have redundant functions in larval-pupal transition

Since Tc-Vn is a newly identified protein, we wanted to determine the role of this ligand in Tribolium. Tc-Egfr signaling has been already involved in the regulation of key processes in embryonic, metamorphic and adult stages43–48. Thus, parental depletion of Tc-Spi, Tc-Egfr, and Tc-Pnt severely reduced egg production, and also resulted in embryos with shorter appendages and problems in the development of thoracic and abdominal segments43,44. To study the function of Tc-Vn in adult and embryonic stages, we injected dsTc-vn into adult females (Tc-vnRNAi animals) and found that, in contrast to what is observed in Tc-Egfr-depleted animals, their ovaries developed properly, and eggs were laid normally (S2A–D Fig). Likewise, the resulting embryos developed as normal and eclosed on a regular schedule (data not shown). Consistent with this finding, whereas the relative expression of Tc-spi was strongly detected in ovaries and embryos the levels of Tc-vn were almost absent, supporting the idea that Tc-vn is dispensable for Tc-Egfr activation in adult and embryonic stages (S2E Fig).

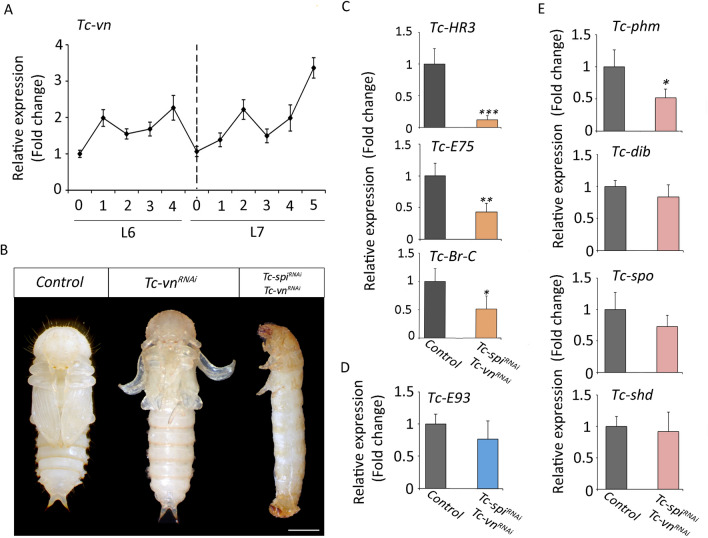

To characterize Tc-Vn during post embryonic stages we next analyzed its expression pattern during the last two larval instars. As Fig. 5A shows, Tc-vn is up-regulated at the first day of L6 and its expression is maintained until the beginning of L7 when it declined. Then, Tc-vn is up-regulated again to reach the highest levels in the prepupal stage similarly to Tc-spi expression. To ascertain the role of the ligand, we next injected dsTc-vn in L6 larvae. Similar to the Tc-spiRNAi phenotype, L6-Tc-vnRNAi animals molted to normal L7 larvae and then to pupae although with some morphological defects (Fig. 5B and S5 Table and Fig. 6). These results demonstrate that Tc-Vn is able to activate the Egfr signaling pathway during the larval-pupal transition.

Figure 5.

Tc-Vn and Tc-Spi activate redundantly the larval-pupal transition in Tribolium. (A) Tc-vn mRNA levels measured by qRT-PCR in penultimate (L6) and ultimate (L7) instar larvae. Transcript abundance values are normalized against the Tc-Rpl32 transcript. Fold changes are relative to the expression of Tc-vn in day 0 of L6 larvae, arbitrarily set to 1. Error bars indicate the SEM (n = 5). (B) L6 larvae were injected with dsMock (Control), dsTc-spi (Tc-spiRNAi) or both dsTc-spi and dsTc-vn simultaneously (Tc-spiRNAi + Tc-vnRNAi) and left until the ensuing molts. Ventral views of Control and Tc-spiRNAi pupae and a Tc-spiRNAi + Tc-vnRNAi larva arrested at the larval-pupal transition. Scale bar represents 0.5 mm. (C) Transcript levels of Tc-Hr3, Tc-E75 and TcBr-C, (D) Tc-E93 and (E) biosynthetic ecdysone genes Tc-phm, Tc-dib, Tc-spok and Tc-shd measured by qRT-PCR in 5-day-old Control, and Tc-spiRNAi + TcvnRNAi L7 larvae. Transcript abundance values were normalized against the Tc-Rpl32 transcript. Average values of three independent datasets are shown with standard errors (n = 7). Asterisks indicate differences statistically significant at *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.001 (t-test) ***p < 0.0001 (t-test).

Figure 6.

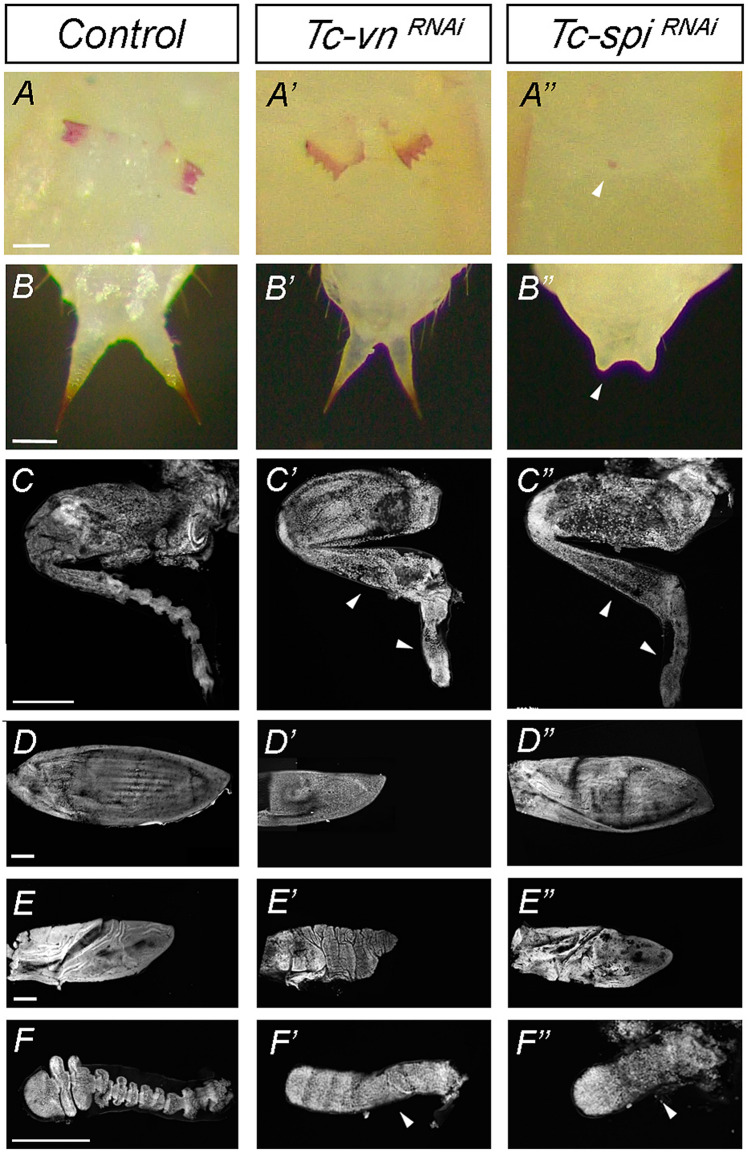

Differential role of Tc-Vn and Tc-Spi in the morphogenesis of pupal structures. Comparison of the external morphology of pupal appendages between (A–F) Control, (A’–F’) Tc-vnRNAi and (A’’–F’’) Tc-spiRNAi pupae. The pupal structures are (A–A’’) Gin traps, (B–B’’) urogomphi, (C–C’’) hindlegs, (D–D’’) elytra, (E–E’’) wing and (F–F’’) antenna. The scale bars represent 0.1 mm in (A–A’’), 0.3 mm in (B–B’’) and 500 μm in (C–C’’), (D–D’’), (E–E’’) and (F–F’’).

The fact that the depletion of neither Tc-vn nor Tc-spi prevents larval-pupal transition raises the possibility that both ligands might redundantly activate the Egfr signaling pathway at this stage of development. To address this question, we interfered Tc-vn and Tc-spi simultaneously in penultimate L6 larvae (Tc-vnRNAi + Tc-spiRNAi animals). Interestingly, all Tc-vnRNAi + Tc-spiRNAi animals molted to L7 but then arrested development at the end of the last larval stage, as Tc-Egfr or Tc-pnt larvae (Fig. 5B and S5 Table). This observation was further confirmed by the analysis of Tc-HR3, Tc-E75, Tc-Br-C mRNA levels, which were strongly reduced in Tc-vnRNAi + Tc-spiRNAi larvae compared to the Control (Fig. 5C). Likewise, the expression of Tc-E93 was not significantly affected indicating that depletion of both ligands does not influence to nature of molt as when the Tc-Egf receptor was depleted (Figs. 1C, 5D). Furthermore, the expression of Tc-phm was also decreased in double knockdown animals whereas the expression levels of Tc-dib, Tc-spok and Tc-shd were not affected (Fig. 5E). Altogether, these results demonstrate that Tc-vn and Tc-spi can act redundantly in the control of the metamorphic transition in Tribolium.

Tc-Spi and Tc-Vn control different aspects of Tribolium metamorphosis

As previously showed, Tc-vnRNAi and Tc-spiRNAi animals were able to pupate, although with morphological defects (compare Figs. 2B, 5B). Interestingly, some of those defects were ligand specific. For example, Tc-spiRNAi pupae lacked gin traps and well developed urogomphi, whereas Tc-vnRNAi pupae showed normal gin traps and urogomphi (Fig. 6A–B”) but presented curved and smaller elytra and wings compared to Tc-spiRNAi animals (Fig. 6D–E’’). In contrast, both knockdown pupae showed similar morphological defects in the segmentation of the distal part of the legs and the antenna (Fig. 6C–C’’,F–F’’). These results suggest that Tc-Vn and Tc-Spi activate the Egfr signaling pathway in a tissue specific manner during the pupal transformation.

Discussion

Egfr signaling in insects is involved in the regulation of multiple processes during organism development such as cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. In addition to these functions, it has been recently shown in Drosophila that regulates the metamorphic transition by controlling ecdysone biosynthesis in the PG20. Interestingly, our study suggests that this role is conserved in the more basal holometabolous insect Tribolium, as the activity of this pathway is specifically required for the larval-pupal transition in this beetle. Furthermore, our study revealed the existence of an additional EGF ligand in Tribolium, the neuroglianin Tc-Vn, which, together with the already described Tc-Spi ligand, activates Egfr in a redundant manner for the induction of the metamorphic transition. In contrast, we report different requirements of both ligands for the formation of pupal structures, such as wings, elytra or gin traps, suggesting a ligand-specific activation of Egfr signaling during metamorphosis.

Egfr signaling regulates larval-pupal transition in Tribolium

In Drosophila Egfr signaling regulates larval-pupal transition through the control of PG size and the expression of ecdysone biosynthetic genes in this gland20. Our results in Tribolium suggest that such regulation might be general feature of holometabolous insects. Several evidences support this possibility: (1) depletion of both Tc-Egfr ligands, Tc-vn and Tc-spi, is required to induce the arrested development phenotype whereas individual depletion of each ligand results in pupa formation with specific morphological defects; (2) depletion of the main transductor of the Egfr signaling Tc-pnt results in the same phenotype; (3) the requirement of Egfr signaling is restricted to the last larval stage as larval-larval molting is unaffected upon inactivation of Tc-Egfr in early larval stages, and (4) depletion of Tc-Egfr or its ligands results in reduced levels of the Halloween gene Tc-phm as well as of several 20E-dependent genes during the larva-pupa transition. However, we need to take into consideration that the use of systemic RNAi to inactivate Tc-Egfr signaling in Tribolium cannot discard an indirect effect on ecdysone production. In this regard, further studies in other holometabolous group of insects would help confirm this evolutionarily conserved trait.

It is interesting to note that 20E controls not only the metamorphic switch but also all the previous larval-larval transitions. The fact that Egfr signaling is involved specifically in triggering pupa formation suggests that other factors might control the production of ecdysone in the previous transitions. In this sense, several transcription factors such as Ventral veins lacking (Vvl), Knirps (Kni) and Molting defective (Mld) have been shown to be involved in the control of ecdysone production during early larval stages in Drosophila57. Orthologues of Drosophila kni and vvl have been identified in Tribolium, showing conserved functions during embryogenesis58,59. Interestingly Tc-vvl has been shown to be a key factor coordinating ecdysteroid biosynthesis as well as molting in larval stages60, supporting the idea that Tc-Vvl also exerts similar function in the PG during early larval development. Nevertheless, further studies are required to confirm the role of these genes and to elucidate ecdysone biosynthesis regulation in all larval transitions.

Then, why is Egfr signaling specifically required during the larva-pupa transition? One possibility is that the peak of 20E required to trigger metamorphosis demands the growth of PG cells to increase the biosynthetic enzyme transcription. Interestingly, this process has recently been related to the nutritional state of the animal. In fact, it has been shown in Drosophila that surpassing a critical weight checkpoint that occurs at the onset of the last larval instar is required for the growth of the PG cells and the increase of ecdysone production1,2,61,62, which implies that PG cells must reach a certain size to produce enough ecdysone to trigger metamorphosis. Similarly, in Tribolium exists a correlation between the attainment of a threshold size, defined as the mass that determines that the animal is in the last larval instar, and the upregulation of key metamorphic genes that induce the metamorphic transition63. Therefore, it is plausible that Egfr signaling is particularly required once the animal reaches the threshold size that determines the initiation of metamorphosis at the ensuing molt. Such activation will ensure the proper increase of ecdysone production to induce the formation of the pupa. In this sense, it is interesting to note that the highest expression of Tc-Egfr is detected at the last larval stage. Similarly, the expression of both ligands Tc-spi and Tc-vn are up-regulated during the late part of the last larval instar, supporting the fact that both ligands are required for Egfr signaling at this stage.

Tribolium possesses two Egfr ligands

To date, a single Tc-Egfr ligand with high sequence similarity to Drosophila Dm-Spi had been identified in the genome of Tribolium probably due to incomplete annotation of the beetle genome and the fact that its depletion in the embryo phenocopied Tc-Egfr knockdown. However, our in silico analysis has revealed the presence of a second Tc-Egf ligand, the neurogulin Tc-Vn, revealing that Tribolium, in contrast to Drosophila, possesses only two EGF ligands. We have confirmed the identity of Tc-Vn in Tribolium by analyzing its protein sequence and its role during development. Phylogenetic analysis clustered Tc-Vn with its coleopteran orthologous proteins. Interestingly, based on the length of the phylogenetic arm, Tc-Vn presents a high range of change, probably due to its minor role on oogenesis and embryogenesis that has reduced the evolutive pressure on Tc-Vn ligand. In contrast, a lower divergence of Tc-Spi is observed, clustering closely to the Drosophila Dm-Egf ligands Dm-Krn and Dm-Spi. This observation is consistent with Tc-Spi exerting a key role during early development as main activator of Tc-Egfr signaling.

Our results indicate that both Egf ligands Tc-Vn and Tc-Spi function redundantly in the control of larval-pupal transition in Tribolium similarly to what occurs in Drosophila. In contrast, the requirement of each ligand is specific for the development of different structures during the pupal stage. Thus, Tc-Vn is required for the formation of wings and elytra, whereas Tc-Spi is responsible of the proper development of gin traps and the urogomphi as well as the mouthpart. In addition, depletion of either Tc-spi or Tc-vn produce distinct defects on the distal part of the leg and the antenna suggesting again a different role on the activation of Egfr signaling in these structures. This different ligand requirement is similar to what has been described in Drosophila. Thus, Dm-Vn is required for wing identity during early imaginal disc development64, whereas later on, the combination of Dm-Spi and Dm-Vn are necessary for vein formation65. Similarly, both ligands Dm-Spi and Dm-Vn control leg patterning and growth37, although Dm-Vn seems to have a predominant role in the formation of the tarsus, the most distal part of the leg40,66. In addition, our data also show that the activation of the Tc-Egfr pathway in oogenesis relay entirely on Tc-Spi. In this context, the similarity of Tc-Spi to the Dm-Egf Drosophila ligand Dm-grk35, a dedicated ligand specific of the ovaries, might explain this exclusive requirement in this process in Tribolium. Therefore, our results confirmed that Egfr signaling is activated by at least two different ligands in most of the holometabolous insects in morphogenetic processes. The different expression and activity of those ligands probably has favored the co-option of Egfr signaling in different processes, from oogenesis to the biosynthesis of ecdysone, contributing to the generation of new organ and shapes along evolution.

Materials and methods

Tribolium castaneum

The enhancer-trap line pu11 of Tribolium (obtained from Y. Tomoyasu, Miami University, Oxford, OH) was reared on organic wheat flour containing 5% nutritional yeast and maintained at 29 °C in constant darkness.

Conserved domains analysis and alignment of Vein sequences

Tc-Vn (TC014604) amino acid sequence was analyzed by different online applications to detect its protein domains. Thus, peptide signal was predicted by SignalP 4.1 software that detect the presence and the location of signal peptide cleavage site67. Conserved sequences of EGF-like and IG-like domains were detected by NCBI's Conserved Domain Database68. PEST region was predicted using EPESTFIND online software that detects PEST motifs as potential proteolytic cleavage sites. Multiple alignment was performed by ClustalW software69. Vein sequence of D. melanosgaster (CG10491), Aedes aegypti (XP_021697922), Operophtera brumata (KOB67206), Bombix mori (XP_004925912), Trichogramma pretiosum (XP_023315843) and Periophthalmus gracilis (XP_020280346), which were used for the alignments, were obtained from GenBank database.

Phylogenetic analysis of Tc-Vn

To understand the phylogenetic relationship of Vein proteins, amino acid sequences from Vein proteins were collected from different insect taxa, including that of Tribolium as well as from four primates species as an outgroup (S3 Table) and aligned using MAFFT70 v7.130b. Ambiguously aligned positions were trimmed using trimAlv1.271, with the parameters –gt 80 and –cons 20. A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using RAXML v8.0.1772 with the PROTGAMMAWAG model.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from individual larva of Tribolium was extracted using the GenElute™ Mammalian Total RNA kit (Sigma). cDNA synthesis was carried out as previously described73,74. Relative transcript levels were determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), using Power SYBR Green PCR Mastermix (Applied Biosystems). To standardize the quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) inputs, a master mix that contained Power SYBR Green PCR Mastermix and forward and reverse primers was prepared to a final concentration of 100 µM for each primer. The qPCR experiments were conducted with the same quantity of tissue equivalent input for all treatments, and each sample was run in duplicate using 2 µl of cDNA per reaction. As a reference, same cDNAs were subjected to qRT-PCR with a primer pair specific Tribolium Ribosomal Tc-Rpl32. All the samples were analyzed on the iCycler iQReal Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences used for qPCR for Tribolium are:

Tc-EGFR-F: 5′-TCACGAGCATGTGGTTATGAT-3′

Tc-EGFR-R: 5′-CTCATTCTCGAGCTGGAAGT-3′

Tc-Pnt-F: 5′-AGAGTTCTCCCTCGAATGCAT-3′

Tc-Pnt-R: 5′-TCTGCAACAACTCCAAGTGCT-3′

Tc-Spi-F: 5′-AACATCACATTCCACACGTAC-3′

Tc-Spi-R: 5′-TCTGCACACTCGCAATTGTAT-3′

Tc-Vn-F: 5′-GAAGTCCAAGACACACAACTC-3′

Tc-Vn-R: 5′-CTTGTATAGGTACCAGGTGTCT-3′

Tc-Kr-h1-F: 5′‐AATCCTCCTGCTCATCCAGCACTA-3′

Tc-Kr-h1-R: 5′‐CAGGATTCGAACTAGGAGGTGTTA-3′

Tc-E93-F: 5′-CTCTCGAAAACTCGGTTCTAAACA-3′

Tc-E93-R: 5′-TTTGGGTTTGGGTGCTGCCGAATT-3′

Tc-HR3-F: 5′-TCACAGAGTTCAGTTGTAAACT-3′

Tc-HR3-R: 5′-TCTCGCTGCTTCTTCGACAT-3′

Tc-E75-F: 5′-CGGTCCTCAATGGAAGAAAA-3′

Tc-E75-R: 5′-TGTGTGGTTTGTAGGCTTCG-3′

Tc-Br-C-F: 5′-TCGTTTCTCAAGACGGCTGAAGTG-3′

Tc-Br-C-R: 5′-CTCCACTAACTTCTCGGTGAAGCT-3′

Tc-Phm-F: 5′-TGAACAAATCGCAATGGTGCCATA-3′

Tc-Phm-R: 5′-TCATGGTACCTGGTGGTGGAACCTTAT-3′

Tc-Rpl32-F: 5′-CAGGCACCAGTCTGACCGTTATG-3′

Tc-Rpl32-R: 5′-CATGTGCTTCGTTTTGGCATTGGA-3′

Larva and adult RNAi injection

Tc-Egfr dsRNA (IB_00647), Tc-Pnt dsRNA (IB_02295), Tc-Spi dsRNA (IB_03555) and Tc-Vn dsRNA (IB_05654) were synthesized by the Eupheria Biotech Company. Control dsRNA consisted of a non-coding sequence from the pSTBlue-1 vector (dsMock). A concentration of 1 µg/µl dsRNA was injected into larvae from penultimate instar and antepenultimate instar. In case of co-injection of two dsRNAs, the same volume of each dsRNA solution was mixed and applied in a single injection. A dose of 1 µg/µl dsRNA was injected into 40 female adults in the abdominal body cavity laterally to avoid damaging genitals as previously described75. Both Tc-EgfrRNAi and Tc-VnRNAi injected females were crossed with wild-type males in order to obtain knockdown embryos.

20E injection

20E (Abcam, ab142425) dissolved in absolute ethanol at a concentration of 1 mg/ml was diluted with distilled water to obtain an optimal concentration of 200 ng /100 nl to inject into Tribolium, as previously reported76. Penultimate staged larvae treated with Egfr dsRNA were injected with a dose of 1 µg of 20E upon molting to the last larval stage.

Microscopy analysis

All ovaries were dissected in PBS, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS and incubated with Phalloidin. The stained ovaries were mounted in Vectashiled with DAPI for epifluorescence microscopy. Dissected pupal appendages, were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI to visualized the nucleus. All pictures were obtained with AxioImager.Z1 (ApoTome 213 System, Zeiss) microscope, and images were subsequently processed using Fuji and Adobe photoshop.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to specially thank Lidia Escoda for technical assistance in the phylogenetic analysis. Support for this research was provided by the Spanish MINECO (Grants CGL2014-55786-P and PGC2018-098427-B-I00 to D.M. and X.F-M.) and by the Catalan Government (2014 SGR 619 to D.M. and X.F-M.). The research has also benefited from FEDER funds. S.C. is a recipient of a pre-doctoral research Grant from the MINECO.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the project was done by S.C., D.M. and X.F-M. S.C. and X.F.-M. performed the experiments. The analysis of the data was conducted by S.C., D.M. and X.F.-M. X.F.-M. wrote the manuscript and S.C. and D.M. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

David Martín, Email: david.martin@ibe.upf-csic.es.

Xavier Franch-Marro, Email: xavier.franch@ibe.upf-csic.es.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-98334-9.

References

- 1.Mirth CK, Riddiford LM. Size assessment and growth control: How adult size is determined in insects. BioEssays. 2007;29:344–355. doi: 10.1002/bies.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamanaka N, Rewitz KF, O’Connor MB. Ecdysone control of developmental transitions: Lessons from drosophila research. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013;58:497–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshiyama T, Namiki T, Mita K, Kataoka H, Niwa R. Neverland is an evolutionally conserved Rieske-domain protein that is essential for ecdysone synthesis and insect growth. Development. 2006;133:2565–2574. doi: 10.1242/dev.02428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshiyama-Yanagawa T, et al. The conserved Rieske oxygenase DAF-36/Neverland is a novel cholesterol-metabolizing enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:25756–25762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.244384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niwa R, et al. Non-molting glossy/shroud encodes a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase that functions in the 'Black Box' of the ecdysteroid biosynthesis pathway. Development. 2010;137:1991–1999. doi: 10.1242/dev.045641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Namiki T, et al. Cytochrome P450 CYP307A1/Spook: A regulator for ecdysone synthesis in insects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;337:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niwa R, et al. CYP306A1, a cytochrome P450 enzyme, is essential for ecdysteroid biosynthesis in the prothoracic glands of Bombyx and Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:35942–35949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404514200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ono H, et al. Spook and Spookier code for stage-specific components of the ecdysone biosynthetic pathway in Diptera. Dev. Biol. 2006;298:555–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rewitz KF, Rybczynski R, Warren JT, Gilbert LI. Identification, characterization and developmental expression of Halloween genes encoding P450 enzymes mediating ecdysone biosynthesis in the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;36:188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warren JT, et al. Molecular and biochemical characterization of two P450 enzymes in the ecdysteroidogenic pathway of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:11043–11048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162375799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren JT, et al. Phantom encodes the 25-hydroxylase of Drosophila melanogaster and Bombyx mori: A P450 enzyme critical in ecdysone biosynthesis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;34:991–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbens YY, Warren JT, Gilbert LI, O’Connor MB. Neuroendocrine regulation of Drosophila metamorphosis requires TGFβ/Activin signaling. Development. 2011;138:2693–2703. doi: 10.1242/dev.063412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colombani J, et al. Antagonistic actions of ecdysone and insulins determine final size in Drosophila. Science. 2005;310:667–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1119432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirth C, Truman JW, Riddiford LM. The role of the prothoracic gland in determining critical weight for metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1796–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Layalle S, Arquier N, Léopold P. The TOR pathway couples nutrition and developmental timing in drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldwell PE, Walkiewicz M, Stern M. Ras activity in the Drosophila prothoracic gland regulates body size and developmental rate via ecdysone release. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1785–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBrayer Z, et al. Prothoracicotropic hormone regulates developmental timing and body size in drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:857–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rewitz KF, Yamanaka N, Gilbert LI, O’Connor MB. The insect neuropeptide PTTH activates receptor tyrosine kinase torso to initiate metamorphosis. Science. 2009;326:1403–1405. doi: 10.1126/science.1176450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimell MJ, et al. Prothoracicotropic hormone modulates environmental adaptive plasticity through the control of developmental timing. Development. 2018;145:deva59699-13. doi: 10.1242/dev.159699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruz J, Martín D, Franch-Marro X. Egfr signaling is a major regulator of ecdysone biosynthesis in the drosophila prothoracic gland. Curr. Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He LL, et al. Mechanism of threshold size assessment: Metamorphosis is triggered by the TGF-beta/Activin ligand Myoglianin. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith WA, Lamattina A, Collins M. Insulin signaling pathways in lepidopteran ecdysone secretion. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:19. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemirembe K, Liebmann K, Bootes A, Smith WA, Suzuki Y. Amino acids and TOR signaling promote prothoracic gland growth and the initiation of larval molts in the tobacco hornworm manduca sexta. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatem NE, Wang Z, Nave KB, Koyama T, Suzuki Y. The role of juvenile hormone and insulin/TOR signaling in the growth of Manduca sexta. BMC Biol. 2015;13:1–2. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu SH, Lin JL, Lin PL, Chen CH. Insulin stimulates ecdysteroidogenesis by prothoracic glands in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009;39:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith, W. & Rybczynski, R. Prothoracicotropic Hormone. in Insect Endocrinology 1–62 (Elsevier, 2012). 10.1016/B978-0-12-384749-2.10001-9.

- 27.Uchibori-Asano M, Kayukawa T, Sezutsu H, Shinoda T, Daimon T. Severe developmental timing defects in the prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH)-deficient silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017;87:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z, Liu X, Yu Y, Yang F, Li K. The receptor tyrosine kinase torso regulates ecdysone homeostasis to control developmental timing in Bombyx mori. Insect Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman M. Complexity of EGF receptor signalling revealed in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1998;8:407–411. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80110-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shilo BZ. Regulating the dynamics of EGF receptor signaling in space and time. Development. 2005;132:4017–4027. doi: 10.1242/dev.02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reich A, Shilo B-Z. Keren, a new ligand of the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor, undergoes two modes of cleavage. EMBO J. 2002;21:4287–4296. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang H, Edgar BA. EGFR signaling regulates the proliferation of Drosophila adult midgut progenitors. Development. 2009;136:483–493. doi: 10.1242/dev.026955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown KE, Kerr M, Freeman M. The EGFR ligands Spitz and Keren act cooperatively in the Drosophila eye. Dev. Biol. 2007;307:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roth S, Shira Neuman-Silberberg F, Barcelo G, Schüpbach T. cornichon and the EGF receptor signaling process are necessary for both anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral pattern formation in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;81:967–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzâlez-Reyes A, Elliott H, St Johnston D. Polarization of both major body axes in drosophila by gurken-torpedo signalling. Nature. 1995;375:654–658. doi: 10.1038/375654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simcox AA, et al. Molecular, phenotypic, and expression analysis of vein, a gene required for growth of the Drosophila wing disc. Dev. Biol. 1996;177:475–489. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell G. Distalization of the Drosophila leg by graded EGF-receptor activity. Nature. 2002;418:781–785. doi: 10.1038/nature00971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yarnitzky T, Min L, Volk T. The Drosophila neuregulin homolog Vein mediates inductive interactions between myotubes and their epidermal attachment cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2691–2700. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cruz J, Bota-Rabassedas N, Franch-Marro X. FGF coordinates air sac development by activation of the EGF ligand Vein through the transcription factor PntP2. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1. doi: 10.1038/srep17806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galindo MI, Bishop SA, Greig S, Couso JP. Leg patterning driven by proximal-distal interactions and EGFR signaling. Science. 2002;297:256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1072311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Neill EM, Rebay I, Tjian R, Rubin GM. The activities of two Ets-related transcription factors required for drosophila eye development are modulated by the Ras/MAPK pathway. Cell. 1994;78:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunner D, et al. The ETS domain protein Pointed-P2 is a target of MAP kinase in the Sevenless signal transduction pathway. Nature. 1994;370:386–389. doi: 10.1038/370386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynch JA, Peel AD, Drechsler A, Averof M, Roth S. EGF signaling and the origin of axial polarity among the insects. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1042–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grossmann D, Prpic NM. Egfr signaling regulates distal as well as medial fate in the embryonic leg of Tribolium castaneum. Dev. Biol. 2012;370:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King B, Denholm B. Malpighian tubule development in the red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum) Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2014;43:605–613. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Angelini DR, Kikuchi M, Jockusch EL. Genetic patterning in the adult capitate antenna of the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev. Biol. 2009;327:240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Angelini DR, Smith FW, Aspiras AC, Kikuchi M, Jockusch EL. Patterning of the adult mandibulate mouthparts in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Genetics. 2012;190:639–654. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.134296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Angelini DR, Smith FW, Jockusch EL. Extent with modification: Leg patterning in the beetle tribolium castaneum and the evolution of serial homologs. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2012;2:235–248. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minakuchi C, Namiki T, Shinoda T. Krüppel homolog 1, an early juvenile hormone-response gene downstream of Methoprene-tolerant, mediates its anti-metamorphic action in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev. Biol. 2009;325:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ureña E, Manjón C, Franch-Marro X, Martín D. Transcription factor E93 specifies adult metamorphosis in hemimetabolous and holometabolous insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:7024–7029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401478111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilbert LI, Rybczynski R, Warren JT. Control and biochemical nature of the ecdysteroidogenic pathway. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2002;47:883–916. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.King-Jones K, Thummel CS. Nuclear receptors: A perspective from Drosophila. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:311–323. doi: 10.1038/nrg1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urban S, Lee JR, Freeman M. A family of rhomboid intramembrane proteases activates all Drosophila membrane-tethered EGF ligands. EMBO J. 2002;21:4277–4286. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yarnitzky T, Min L, Volk T. The Drosophila neuregulin homolog Vein mediates inductive interactions between myotubes and their epidermal attachment cells. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:2691–2700. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Groenen LC, Nice EC, Burgess AW. Structure-function relationships for the EGF/TGF-alpha family of mitogens. Growth Factors. 1994;11:235–257. doi: 10.3109/08977199409010997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schnepp B, Grumbling G, Donaldson T, Simcox A. Vein is a novel component in the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor pathway with similarity to the neuregulins. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2302–2313. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Danielsen ET, et al. Transcriptional control of steroid biosynthesis genes in the drosophila prothoracic gland by ventral veins lacking and knirps. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cerny AC, Grossmann D, Bucher G, Klingler M. The Tribolium ortholog of knirps and knirps-related is crucial for head segmentation but plays a minor role during abdominal patterning. Dev. Biol. 2008;321:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burns KA, Gutzwiller LM, Tomoyasu Y, Gebelein B. Oenocyte development in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Dev. Genes Evol. 2012;222:77–88. doi: 10.1007/s00427-012-0390-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ko C, Chaieb A, Koyama L, Sarwar T. The POU factor ventral veins lacking/drifter directs the timing of metamorphosis through ecdysteroid and juvenile hormone signaling. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:1004425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Callier V, Nijhout HF. Body size determination in insects: A review and synthesis of size- and brain-dependent and independent mechanisms. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2013;88:944–954. doi: 10.1111/brv.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rewitz KF, Yamanaka N, O’Connor MB. Developmental checkpoints and feedback circuits time insect maturation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2013;103:1–33. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385979-2.00001-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chafino S, et al. Upregulation of E93 gene expression acts as the trigger for metamorphosis independently of the threshold size in the beetle tribolium castaneum. Cell Rep. 2019;27:1039–1049.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang SH, Simcox A, Campbell G. Dual role for Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in early wing disc development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2271–2276. doi: 10.1101/gad.827000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Celis JF. Pattern formation in the Drosophila wing: The development of the veins. BioEssays. 2003;25:443–451. doi: 10.1002/bies.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Galindo MI, Bishop SA, Couso JP. Dynamic EGFR-Ras signalling in Drosophila leg development. Dev. Dyn. 2005;233:1496–1508. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Petersen TN, Brunak S, Von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: Discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D200–D203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cruz J, et al. Quantity does matter: Juvenile hormone and the onset of vitellogenesis in the German cockroach. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;33:1219–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mané-Padrós D, et al. The hormonal pathway controlling cell death during metamorphosis in a hemimetabolous insect. Dev. Biol. 2010;346:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tomoyasu Y, Denell RE. Larval RNAi in Tribolium (Coleoptera) for analyzing adult development. Dev. Genes Evol. 2004;214:575–578. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tatun N, Kumdi P, Tungjitwitayakul J, Sakurai S. Effects of 20-hydroxyecdysone on the development and morphology of the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Eur. J. Entomol. 2018;115:424–431. doi: 10.14411/eje.2018.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.