Abstract

Background

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics is a public health problem in low-income and middle-income countries. Although the association of antibiotics with atopic and allergic diseases has been established, most studies focused on prenatal exposure and the occurrence of disease in infants or young children.

Objective

To investigate the association of preschool use of antibiotics with atopic and allergic skin diseases in young adulthood.

Design

Population-based retrospective cohort.

Setting and participants

The first-year college students (n=20 123) from five universities were investigated. The sampled universities are located in Changsha, Wuhan, Xiamen, Urumqi and Hohhot, respectively.

Methods

We conducted a dermatological field examination and a questionnaire survey inquiring the participants about the frequency of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and the preschool antibiotics use (prior to 7 years old). The two-level probit model was used to estimate the associations, and adjusted risk ratio (aRR) and 95% CI were presented as the effect size.

Results

A total of 20 123 participants with complete information was included in the final analysis. The frequent antibiotics use intravenously (aRR 1.36, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.62) and orally (aRR 1.18, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.38) prior to 7 years old was significantly associated with atopic dermatitis in young adulthood. Similar trends could be observed in allergic skin diseases among those who use antibiotics orally and intravenously, with RRs of 1.16 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.34) and 1.33 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.57), respectively.

Conclusions

Preschool URTI and antibiotics use significantly increases the risk of atopic and allergic skin diseases in young adulthood.

Keywords: allergy, adult dermatology, eczema

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main outcomes were diagnosed by specialists instead of self-report.

This study provides a relatively large and representative sample, and sufficient variations in geographical regions and sociodemographic subgroups, as well as the random effect at the university level, was fitted by the two-level models, resulting in an unbiased estimation of associations.

Recall bias in the measurement of exposure to antibiotics might have been introduced, which could not be ignored in most retrospective studies.

We lacked the information about the type and dose of antibiotics, and there might be a reversed causal relationship because antibiotics could be used in the treatment of atopic dermatitis and other conditions accompanied by a bacterial infection.

Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of atopic and allergic conditions such as asthma, allergic rhinitis (AR), food allergies and atopic dermatitis (AD) among the worldwide population have significantly increased during the past several decades.1–3 An area of environmental change that may be responsible for the increase of allergic and atopic diseases is the growing use of medications that may alter the development of the human microbiome.4 It also seems that the use of some antibiotics, which can directly cause intestinal dysbiosis and affect the human microbiome and increase the risk for allergy development, is of particular concern in light of accumulating evidence.5–7

Furthermore, overuse and misuse of antibiotics is a severe public health problem worldwide, especially in low-income and middle-income countries. In the last decade, prescriptions of broad-spectrum antibiotics increased by 49% in children under 5 years and doubled in children aged 5–17 years, concomitant with the increasing prevalence of allergic diseases.8 9 In China, 70% of outpatients attending primary care facilities with colds were inappropriately treated with antibiotics, often by intravenous infusion. The situation is even worse in children because many parents demand treatment with antibiotics.10 However, most upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) in children are viral, for which antibiotics are unnecessary.11–13

The association between the use of antibiotics and atopic and allergic diseases has been observed in longitudinal studies. But most studies focused on antibiotics use during pregnancy or infancy when early colonisation is initiated by maternal microbes.14–17 With the childhood microbiome transition owing to alterations in food and exposure to more diverse microbes in external environments, children in preschool age (<7 years) are at higher risks of URTI infection and antibiotics treatment. However, the effect of antibiotics used during this period on atopic and allergic skin diseases that occurred in their young adulthood is not clear. The objective of this study was to evaluate the hypothesis that exposure to antibiotics in preschool age is associated with an increased risk of allergic and atopic skin diseases in young adulthood. We tested this hypothesis by conducting a retrospective study in college students.

Materials and methods

Study setting and design

This was a retrospective cohort study based on the data from the China College Student Skin Health Study.18 The first-year college students from five universities were investigated. They underwent a health examination and completed a questionnaire survey. The sampled universities are located in Changsha, Wuhan, Xiamen, Urumqi and Hohhot, respectively.

Exposure assessment

Two semiquantitative questions served as the proxy measures of the frequency of antibiotics exposure in preschool age, with detailed explanations for the definitions of URTI and antibiotics. In our study, the definition of URTI refers to a series of acute illnesses that have an effect on the upper respiratory system including the common cold, acute otitis media, tonsillitis/tonsillopharyngitis, sinusitis and recurrent sinusitis.19 The first question was ‘How often did you have URTI in your preschool-age or before 7 years old’, with three potential responses: ‘≤1 time/year’, ‘2–3 times/year’, and ‘4 or more times/year’. The second question was ‘How often did you receive antibiotics treatment when you had a URTI’, with four responses: ‘rare’, ‘occasional’, ‘often, orally’ and ‘often, intravenously’.

Outcome assessment

Diagnosis of skin diseases and inquiry of disease history were performed by dermatologists during the field survey. All subjects underwent skin examination by resident doctors in dermatology, and the diagnoses were further validated by senior dermatologists. Clinical manifestation, disease history and family history were inquired about and inspections were conducted to diagnose skin diseases. For recurrent skin diseases, only those with current symptoms and cutaneous lesions were diagnosed as cases. AD was diagnosed according to the Williams criteria.20 Hand eczema was diagnosed according to eczema (rash) on the fingers, finger webs, palms or back of hands, which had appeared once and continued for at least 2 weeks or had appeared several times or had been persistent. Allergies and urticaria were diagnosed by clinical manifestations, potential triggers, and histories. Asthma, AR and allergic conjunctivitis were self-reported according to doctors’ diagnoses. We also combined some of the outcomes. Atopic march is an apparent progression of allergic diseases from AD, to allergic asthma (AA) to AR and allergic conjunctivitis.21 22 We include the conditions of AD, AA, AR and allergic conjunctivitis for the outcome of the atopic march. Allergic skin disease includes allergic reactions to food/drug/light, contact dermatitis and urticaria. Participants with a history of atopic/allergic conditions but without the current disease are excluded.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status (annual family income and parental highest educational level), family history, behavioural factors (dietary, passive smoking and bathing habits) were inquired by the questionnaire. The questionnaire used in the study was shown in online supplemental material 1.

bmjopen-2020-047768supp001.pdf (223.6KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as number (%), and the between-group difference was tested using the χ2 test. Two-level probit regression models (individual as level 1 and university as level 2) were used to estimate the associations of preschool exposure to antibiotics with atopic skin diseases in young adulthood, adjusting for level-1 covariates (gender, ethnicity, annual household income and parental education) and level-2 random effects. The effect size was presented as relative risk (RR) and 95% CI. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. Statistical analysis was performed in SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute).

Patient and public involvement statement

This is a retrospective cohort study based on the data from the China College Student Skin Health Study (CCSSHS). The first-year college students from five universities were recruited and investigated. They underwent a health examination and completed a questionnaire survey, and the results will be disseminated to study participants by a medical examination report. Participants were not involved in the design and implementation of the study.

Results

A total of 27 144 registries for new enrolment was identified; among them, 21 086 (77.7%) consented to participate, and 20 123 (74.1%) who underwent the health examination and completed the online questionnaire survey were included in the final analyses. The mean age was 18.3±0.8 years and 10 283 (51.1%) were men. The characteristics of participants in the study are shown in table 1. The prevalence rates of chronic urticaria, allergic reactions to food/drug/light, hand eczema and AD were 1.89%, 2.27%, 3.35% and 3.86%, respectively. The prevalence rates of AD and allergic skin disease were 3.86% and 4.14%, respectively (figure 1 and online supplemental table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the present study (N=20 123)

| Characteristics | N | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 10 283 | 51.1 |

| Female | 9840 | 48.9 |

| Income (CNY) | ||

| <¥10 000 | 2168 | 10.8 |

| ¥10 000–¥29 999 | 4376 | 21.7 |

| ¥30 000–¥49 999 | 3465 | 17.2 |

| ¥50 000–¥99 999 | 4417 | 22.0 |

| ¥100 000–¥199 999 | 4063 | 20.2 |

| ≥¥200 000 | 1634 | 8.1 |

| Parental highest education | ||

| Primary school | 1320 | 6.6 |

| Middle school | 5316 | 26.4 |

| High school | 5021 | 24.9 |

| College and above | 8466 | 42.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Han Chinese | 16 218 | 80.6 |

| Other ethnicities | 3905 | 19.4 |

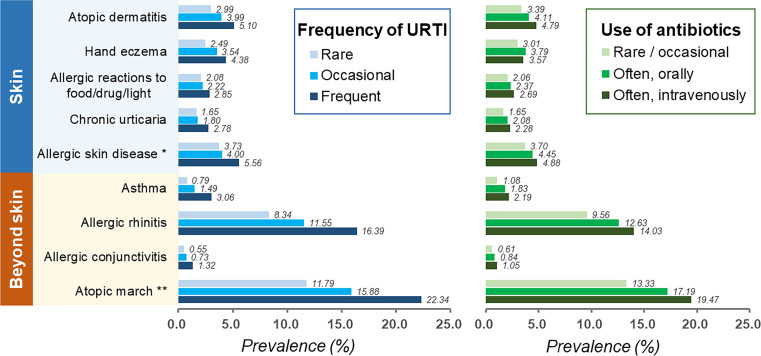

Figure 1.

The prevalence of atopic and allergic diseases in exposure vs non-exposure group of antibiotics and URTI. URTI, upper respiratory tract infection. *Allergic skin disease includes allergic reactions to food/drug/light, contact dermatitis and urticaria. **Atopic march refers to atopic dermatitis, allergic asthma, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis.

In general, URTI and the use of antibiotics were significantly associated with atopic and allergic diseases dose-dependently (figure 1 and online supplemental table 1). For example, the prevalence of AD increased from 3.39% to 4.11% and 4.79% in participants who reported rare or occasional use, frequent oral use and frequent intravenous use of antibiotics, respectively. Consistent trends could be observed in all atopic and allergic diseases and their combinations.

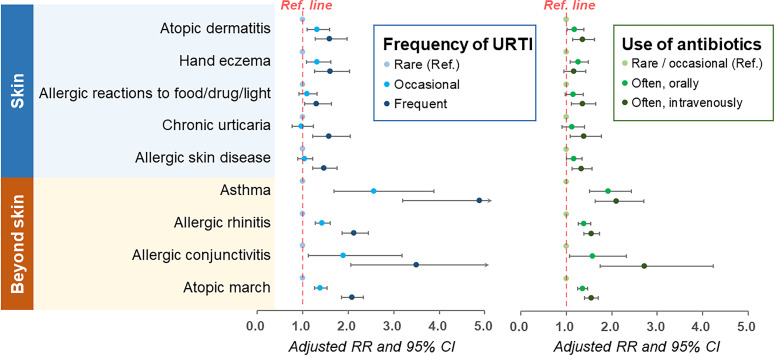

After adjustments for sociodemographic factors (figure 2 and online supplemental table 2), URTI and the use of antibiotics were significantly associated with atopic/allergic skin diseases in dose-response manners. For instance, compared with those reporting rare or occasional use of antibiotics, the RRs for AD in participants who reported frequent oral administration and intravenous injection of antibiotics was 1.18 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.39) and 1.36 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.62), respectively. For other allergies or atopic diseases of skin or beyond skin, the correlations were highly consistent despite some variations in the magnitude of the association.

Figure 2.

Association of early-life exposure to antibiotics with the risk of atopic/allergic diseases later in life. RR, risk ratio; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

Furthermore, we have provided the data on the health-seeking behaviour dealing with a cold or fever in preschool age (shown in table 2), and we found there were 66.2% among participants with the atopic march and 64.7% among participants with allergic skin disease showed that they/their parents would like to seek antibiotics treatment when they had a cold/fever in their preschool age. In those without atopic/allergic diseases, this proportion ratio was 61.5%. Indeed, we found a moderate but significant difference in the seeking behaviour of antibiotic treatment between those with allergic skin disease/atopic march and healthy participants (p=0.001). Similar trends could be seen in AD patients and non-patients (p=0.034).

Table 2.

Health-seeking behaviour when dealing with a cold or fever in the preschool age*

| Disease condition | Total | Health seeking behaviour, n (%)† | ||||

| Ignore them | Drink water or have a rest | Receive antibiotics orally or intravenously | Receive chinese traditional medicine orally | Unknown | ||

| Skin | ||||||

| Atopic dermatitis | 776 | 20 (2.6) | 370 (47.6) | 512 (65.9) | 194 (25.0) | 3 (0.3) |

| Hand eczema | 675 | 32 (4.7) | 343 (50.8) | 430 (63.7) | 149 (22.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Allergic reactions to food/drug/light | 456 | 9 (2.0) | 227 (49.7) | 286 (62.7) | 95 (20.8) | 1 (0.2) |

| Chronic urticaria | 381 | 8 (2.1) | 158 (41.4) | 257 (67.4) | 100 (26.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| Allergic skin disease‡ | 833 | 17 (2.0) | 384 (46.0) | 539 (64.7) | 194 (23.2) | 2 (0.2) |

| Beyond skin | ||||||

| Atopic march§ | 3139 | 66 (2.1) | 1542 (49.1) | 2081 (66.2) | 728 (23.1) | 12 (0.3) |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 153 | 4 (2.6) | 83 (54.2) | 107 (69.9) | 36 (23.5) | 0 (0) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 2273 | 42 (1.8) | 1135 (49.9) | 1515 (66.6) | 532 (23.4) | 8 (0.4) |

| Asthma | 303 | 7 (2.3) | 154 (50.8) | 206 (67.9) | 70 (23.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| Without atopic/allergic diseases | 16 343 | 597 (3.7) | 7761 (47.4) | 10 057 (61.5) | 3058 (18.7) | 76 (0.4) |

*Multiple selections are allowed in the questionnaire.

†Proportion ratios in populations.

‡Allergic skin disease includes allergic reactions to food/drug/light, contact dermatitis and urticaria.

§Atopic march refers to atopic dermatitis, allergic asthma, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis.

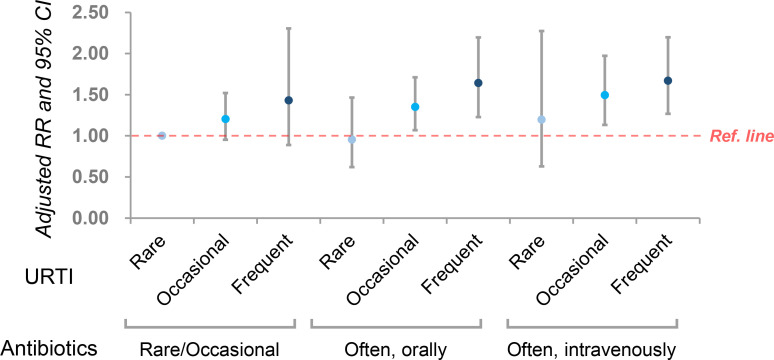

Besides, because our study was not a prospective cohort, it was difficult to know if antibiotic use was ahead of suffering from AD. We further evaluated the joint effect of URTI and antibiotics on AD by including an interaction term in the model. As shown in figure 3, in each category of antibiotic use, the frequency of URTI was positively associated with the risk of AD. Vice versa, in each category of URTI, antibiotic use was positively associated with AD according to the effect size, despite some insignificant results in categories with a small sample size.

Figure 3.

The joint effect of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and antibiotics on AD after including an interaction term in the model. AD, atopic dermatitis; RR, risk ratio.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study demonstrated that preschool exposure to antibiotics, either through oral administration or intravenous infusion, was associated with increased risks of having allergic and atopic skin diseases in young adulthood. Participants who reported frequent URTI in preschool-age also had higher risks of allergies and atopy.

Similar trends were identified in previous observational studies that early-life antibiotic use was associated with an increased risk of eczema, but there were still some inconsistent results.23 24 Meta-analysis including 22 studies with 394 517 patients concluded that children with antibiotics exposure in the first 2 years had increased odds of atopic eczema with an OR of 1.26 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.37). Notably, the onset age of the outcomes in the included studies was the period of childhood (<12 years old).7 A large population-based retrospective cohort study in twins showed that antibiotic use was also associated with an increased risk of eczema. However, the relationship between early-life antibiotic use and eczema was likely to be confounded by shared familial environment and genetic factors.25 However, current data lacked the information regarding the atopic and allergic skin diseases occurred in late adolescence to early adulthood, while we first investigated the effects of preschool antibiotic in a retrospective study and revealed a positive association. Chinese parents were found to pay close attention to the preschool health of children and keep a non-exclusion attitude to antibiotics use. Using antibiotics at home, seeking medical care and use antibiotics in the hospital for children was pervasive in China when parents dealing with children’s respiratory tract infections. However, the results should be discussed with caution as a doctor seeking behaviour varies a lot in populations. In this setting, children with AD will seek a doctor frequently and more likely get a URTI diagnosis if they also have a cold. Equally, children with asthma and wheezing will more frequently get a URTI diagnosis and are more likely to get an antibiotic.

Evidence showed that AD was the first manifestation of an atopic phenotype that begins in early childhood and the progression from AD to the diseases such as food allergy, asthma, and AR were more likely to be shown in adolescence.22 26 27 The mechanisms behind the march from AD to allergic airway diseases and allergic conjunctivitis likely arise from initial epicutaneous allergen sensitisation inducing robust local and systemic type 2 immune responses with increased production of type 2 cytokines including interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, IL-31 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin.28 29 Most studies were prone to make these responses responsible for the commonly shared pathogenesis of cutaneous, airway and conjunctiva inflammation, supporting the view that AD is not merely a disease confined to the skin, but is in fact, a systemic disease.30 31 Therefore, it could be explained that the increased risks beyond skin manifestations in young adulthood were consistent with those of skin diseases and some with even greater effect sizes. While not fully understood, the underlying mechanism of the association between antibiotics and atopic and allergic diseases can be elucidated by microbial diversity. The gut microbial community is dynamic and variable during the first 3 years of life, before stabilising to an adult-like state.32 Studies have demonstrated continued development through childhood into the teenage years.33 34 Dietary intake plays a key role in the development period of the gut microbiome. Breast-fed infants have microbiota enriched in Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus and Bifidobacterium. Studies have shown that human milk isolates contain symbiotic and potentially probiotic microbes and supplementation of Bifidobacteria was found to be effective in the primary prevention of allergic diseases.35–37 But among children of preschool age, the dominance of Bifidobacterium diminishes with the alteration in dietary intake.15 On the other hand, the high prevalence of antibiotic use may also lead to a concurrent increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria.38 39 Antibiotic-treated children have a less diverse gut microbiota and less stable communities. Antibiotic therapy affects microbiome variety and thus may increase the risk of atopic diseases.40 41

In our study, increased risks of atopic march or allergic diseases were observed in students who reported frequent URTI. Another potential explanation was related to the infections which could also affect microbial conditions. Except for the change in diet, children of preschool age tend to be exposed to more diverse microbes and infectious diseases including URTI in kindergarten or external environments. Respiratory viral infections, in particular, have been shown to initiate a cascade of host immune responses altering microbial growth in the respiratory tract and gut,42 which could further shape atopic microenvironments.

Several limitations should be noted, and the results should be interpreted with caution. First, recall bias in the measurement of exposure to antibiotics might have been introduced. While recall bias on the frequency of antibiotics use and URTIs should not be ignored, this is a limitation in most retrospective studies. Besides, selection bias might also be introduced as students with skin conditions might be more interested to participate and recall carefully. We are not able to validate the medical records because China does not have a registry system for primary care, and a large number of patients with mild conditions also visit doctors in secondary and tertiary hospitals. While participants could obtain the information from their parents, but unfortunately, we could not evaluate the extent of recall bias. Similarly, for the conditions of the disease including asthma, AR, and allergic conjunctivitis, which we collected based on both clinical diagnosis and questionnaire data, we could not ignore the atopic conditions in the past that might not be existing anymore, though in previous studies, the ‘atopic march’ referred to the sequential development of symptoms and was considered to be not strictly limited by the occurring time.43 44 Those will be in our further consideration in future studies.

Second, there was a lack of information about the type and dose of antibiotics, as well as some antibiotic use for the treatment of low respiratory tract infection, skin infections and other infections, which was not collected while could also affect the microbiome. So we could not attribute the associations to specific antibiotics use. Third, we noticed that some factors related to the allergic/atopic conditions in preschool age could be ignored, such as prematurity, the doctor seeking behaviour, etc, and we had difficulty in fully collecting of related information and need to explain the results with caution. Last but not least, there might be a reversed causal relationship because antibiotics could be used in the treatment of AD and other conditions accompanied by bacterial infection. We assessed the role of URTI and antibiotics separately, because the two variables were significantly correlated (contingency coefficient=0.4, p<0.001) and were therefore not included in the same model to avoid collinearity and biased estimation of parameters. It is possible that the association of URTI with AD and allergies is confounded by antibiotics and vice-versa.

However, both infection and antibiotics may be correlated with allergies/atopies, with different mechanisms. Although under the hygiene hypothesis, exposure to pathogens during infancy and early childhood has been proposed to explain the lower prevalence of asthma and other atopic diseases among children in developing countries,45 46 some studies showed that early respiratory infections could not protect against atopic eczema or recurrent wheezing, but could drive the development of atopic disease.47–51 Atopic sensitisation, a process of generation of specific immunoglobulin E (sIgE) when exposed to an innocuous antigen, was common to all allergic diseases. As preschool URTI most probably represents viral infections in the majority of cases, some studies investigated a potential mechanistic explanation for how a respiratory viral infection could drive the development of atopic sensitisation and disease. Martorano and Grayson52 used a Sendai virus to establish the mouse model mimicking a human limited respiratory syncytial virus infection and found that Sendai virus infection could promote the crosslinking of high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) on the lung conventional dendritic cells, which led to the production of the CC chemokine ligand (CCL) 28, recruiting IL-13 and driving the development of mucous cell metaplasia and airway hyperreactivity. Another animal study found that except for the increase of sIgE against Sendai virus in mice, there was also a large increase in total IgE and it remained elevated long after the viral infection being resolved.53 This notion has further been fuelled by findings that mice infected with the influenza virus developed virus-specific mast cell degranulation in the skin, indicating a possible pathway of viral infections that could mediate allergic symptoms.54 Besides, the respiratory viral infections were shown to initiate a cascade of host immune responses altering microbial growth in the respiratory tract and gut.42 55 However, we cannot ignore that infections that do not require antibiotics are not captured in our design, such that it is difficult to assess whether the observed association is caused by a specific infection or antibiotics because they occur simultaneously in many cases.

Our study also has strengths. The primary strength is that the sample size for the retrospective cohort study was large. Second, the outcomes were diagnosed by specialists. In contrast, some previous studies used self-reported diagnoses that might introduce misclassification bias. Third, the study had a relatively large and representative sample, and sufficient variations in geographic regions and sociodemographic subgroups. The random effect at the university level was fitted by the 2-level models, resulting in an unbiased estimation of associations.

To conclude, preschool children exposed to URTI or antibiotics may be at higher risks of atopic and allergic skin diseases in their young adulthood, especially among those who frequently had URTI or received antibiotics by intravenous infusion. Our study implies that unnecessary antibiotics treatment in children should be avoided to prevent the occurrence of atopic and allergic diseases in their later life. Prospective studies that consider the type and dose of antibiotics are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals and institutions who have made substantial contribution to the establishment of the cohort: Central South University (Lei Cai, Duling Cao, Qin Cao, Chao Chen, Liping Chen, Menglin Chen, Mengting Chen, Xiang Chen, Qing Deng, Xin Gao, Yihuan Gong, Jia Guo, Yeye Guo, Rui Hu, Xin Hu, Chuchu Huang, Huining Huang, Kai Huang, Xiaoyan Huang, Yuzhou Huang, Danrong Jing, Xinwei Kuang, Li Lei, Jia Li, Jiaorui Li, Jie Li, Keke Li, Peiyao Li, Yajia Li, Yayun Li, Yangfan Li, Dan Liu, Dihui Liu, Fangfen Liu, Nian Liu, Panoan Liu, Runqiu Liu, Hui Lu, Wenhua Lu, Yan Luo, Zhongling Luo, Manyun Mao, Mengping Mao, Yuyan Ouyang, Shiyao Pei, Qunshi Qin, Ke Sha, Lirong Tan, Ling Tang, Ni Tang, Yan Tang, Ben Wang, Yaling Wang, Tianhao Wu, Yun Xie, Siyu Yan, Sha Yan, Bei Yan, Xizhao Yang, Lin Ye, Hu Yuan, Taolin Yu, Yan Yuan, Yi Yu, Rui Zhai, Jianghua Zhang, Jianglin Zhang, Mi Zhang, Xingyu Zhang, Zhibao Zhang, Shuang Zhao, Yaqian Zhao, Kuangbiao Zhong, Lei Zhou, Youyou Zhou, Zhe Zhou, Susi Zhu); Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Xiangjie An, Siqi Da, Yaqi Dong, Yangxue Fu, Lixie Gao, Han Han, Biling Jiang, Jiajia Lan, Jun Li, Xiaonan Li, Yan Li, Liquan Liu, Yuchen Lou, Pu Meng, Yingli Nie, Gong Rao, Shanshan Sha, Xingyu Su, Huinan Suo, Rongying Wang, Jun Xie, Yuanxiang Yi, Jia Zhang, Qiao Zhang, Li Zhu, Yanming Zhu); Xiamen University (Zhiming Cai, Lina Chen, Xiaozhu Fu, Hongjun Jiang, Guihua Luo, Jianbing Xiahou, Binxiang Zheng); People's Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Jianxia Chen, Xiaomin Chen, Xinqi Chen, Li Dai, Yanyan Feng, Fanhe Jiang, Lan Jin, Qingyu Ma, Qun Shi, Hongbo Tang, Fang Wang, Zhen Wang, Xiujuan Wu, Kunjie Zhang, Yu Zhang); Xinjiang Medical University (Huagui Li, Jianguang Li, Lei Shi); Inner Mongolia Medical University (Chao Tian, Wei Wang, Rina Wu, Hongjun Xing, Baogui Yang).

Footnotes

Contributors: YX is the corresponding author and have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept: YX. Design: MS and YX. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: YL, DJ and YH. Drafting of the manuscript: YL. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: MS, XK and YL. Administrative, technical or material support: JS, JL, JT, SS, XW, XK and BW. Supervision: XC.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key Research & Development Project ‘Precision Medicine Initiative’ of China (2016YFC0900802) and the Programme of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (111 Project, No. B20017).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted according to the guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki. All procedures involving patients were approved by the institutional research ethics boards of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (Changsha, China) (#201709993). Informed consent was obtained from all the students before the investigation.

References

- 1.Pawankar R. Allergic diseases and asthma: a global public health concern and a call to action. World Allergy Organ J 2014;7:12. 10.1186/1939-4551-7-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platts-Mills TAE. The allergy epidemics: 1870-2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:3–13. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: Isaac phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006;368:733–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitre E, Susi A, Kropp LE, et al. Association between use of Acid-Suppressive medications and antibiotics during infancy and allergic diseases in early childhood. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172:e180315. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J-Y, Liu L-F, Chen C-Y, et al. Acetaminophen and/or antibiotic use in early life and the development of childhood allergic diseases. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1087–99. 10.1093/ije/dyt121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DH, Han K, Kim SW. Effects of antibiotics on the development of asthma and other allergic diseases in children and adolescents. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2018;10:457–65. 10.4168/aair.2018.10.5.457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmadizar F, Vijverberg SJH, Arets HGM, et al. Early-Life antibiotic exposure increases the risk of developing allergic symptoms later in life: a meta-analysis. Allergy 2018;73:971–86. 10.1111/all.13332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee GC, Reveles KR, Attridge RT, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States: 2000 to 2010. BMC Med 2014;12:96. 10.1186/1741-7015-12-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Versporten A, Bielicki J, Drapier N, et al. The worldwide antibiotic resistance and prescribing in European children (ARPEC) point prevalence survey: developing hospital-quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing for children. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:1106–17. 10.1093/jac/dkv418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biezen R, Grando D, Mazza D, et al. Dissonant views - GPs' and parents' perspectives on antibiotic prescribing for young children with respiratory tract infections. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20:46. 10.1186/s12875-019-0936-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei X, Zhang Z, Walley JD, et al. Effect of a training and educational intervention for physicians and caregivers on antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in children at primary care facilities in rural China: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e1258–67. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30383-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Song X, Yang T, et al. A systematic review of antibiotic prescription associated with upper respiratory tract infections in China. Medicine 2016;95:e3587. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding L, Sun Q, Sun W, et al. Antibiotic use in rural China: a cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitudes and self-reported practices among caregivers in Shandong Province. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:576. 10.1186/s12879-015-1323-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smith C, et al. Early exposure to infections and antibiotics and the incidence of allergic disease: a birth cohort study with the West Midlands general practice research database. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;109:43–50. 10.1067/mai.2002.121016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kundu P, Blacher E, Elinav E, et al. Our gut microbiome: the evolving inner self. Cell 2017;171:1481–93. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida S, Ide K, Takeuchi M, et al. Prenatal and early-life antibiotic use and risk of childhood asthma: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2018;29:490–5. 10.1111/pai.12902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusel MMH, de Klerk N, Holt PG, et al. Antibiotic use in the first year of life and risk of atopic disease in early childhood. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:1921–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen M, Xiao Y, Su J, et al. Prevalence and patient-reported outcomes of noncommunicable skin diseases among college students in China. JAAD Int 2020;1:23–30. 10.1016/j.jdin.2020.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Johnston M, et al. Applying psychological theories to evidence-based clinical practice: identifying factors predictive of managing upper respiratory tract infections without antibiotics. Implement Sci 2007;2:26. 10.1186/1748-5908-2-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams HC, Burney PG, Pembroke AC, et al. The U.K. working party's diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. III. independent hospital validation. Br J Dermatol 1994;131:406–16. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic March. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:S118–27. 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill DA, Spergel JM. The atopic March: critical evidence and clinical relevance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;120:131–7. 10.1016/j.anai.2017.10.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metzler S, Frei R, Schmaußer-Hechfellner E, et al. Association between antibiotic treatment during pregnancy and infancy and the development of allergic diseases. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2019;30:423–33. 10.1111/pai.13039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsakok T, McKeever TM, Yeo L, et al. Does early life exposure to antibiotics increase the risk of eczema? A systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2013;169:983–91. 10.1111/bjd.12476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slob EMA, Brew BK, Vijverberg SJH, et al. Early-Life antibiotic use and risk of asthma and eczema: results of a discordant twin study. Eur Respir J 2020;55. 10.1183/13993003.02021-2019. [Epub ahead of print: 23 04 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson E, Hershey GKK. Contribution of an impaired epithelial barrier to the atopic March. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;120:118–9. 10.1016/j.anai.2017.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belgrave DCM, Granell R, Simpson A, et al. Developmental profiles of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis: two population-based birth cohort studies. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001748. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akei HS, Brandt EB, Mishra A, et al. Epicutaneous aeroallergen exposure induces systemic Th2 immunity that predisposes to allergic nasal responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118:62–9. 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cianferoni A, Spergel J. The importance of TSLP in allergic disease and its role as a potential therapeutic target. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2014;10:1463–74. 10.1586/1744666X.2014.967684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asada Y, Nakae S, Ishida W, et al. Roles of epithelial cell-derived type 2-Initiating cytokines in experimental allergic conjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:5194–202. 10.1167/iovs.15-16563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han H, Xu W, Headley MB, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)-mediated dermal inflammation aggravates experimental asthma. Mucosal Immunol 2012;5:342–51. 10.1038/mi.2012.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 2012;486:222–7. 10.1038/nature11053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hollister EB, Riehle K, Luna RA, et al. Structure and function of the healthy pre-adolescent pediatric gut microbiome. Microbiome 2015;3:36. 10.1186/s40168-015-0101-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agans R, Rigsbee L, Kenche H, et al. Distal gut microbiota of adolescent children is different from that of adults. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2011;77:404–12. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01120.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heikkilä MP, Saris PEJ. Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus by the commensal bacteria of human milk. J Appl Microbiol 2003;95:471–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bäckhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe 2015;17:852. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enomoto T, Sowa M, Nishimori K, et al. Effects of bifidobacterial supplementation to pregnant women and infants in the prevention of allergy development in infants and on fecal microbiota. Allergol Int 2014;63:575–85. 10.2332/allergolint.13-OA-0683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiltunen T, Virta M, Laine AL. Antibiotic resistance in the wild: an eco-evolutionary perspective[J]. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1712;2017:372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawkey PM, Jones AM. The changing epidemiology of resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;64 Suppl 1:i3–10. 10.1093/jac/dkp256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penders J, Stobberingh EE, van den Brandt PA, et al. The role of the intestinal microbiota in the development of atopic disorders. Allergy 2007;62:1223–36. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01462.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abrahamsson TR, Jakobsson HE, Andersson AF, et al. Low diversity of the gut microbiota in infants with atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:434–40. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanada S, Pirzadeh M, Carver KY, et al. Respiratory viral infection-induced microbiome alterations and secondary bacterial pneumonia. Front Immunol 2018;9:2640. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wahn U. What drives the allergic March? Allergy 2000;55:591–9. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spergel JM. From atopic dermatitis to asthma: the atopic March. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;105:99–106. 10.1016/j.anai.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. The immunology of the allergy epidemic and the hygiene hypothesis. Nat Immunol 2017;18:1076–83. 10.1038/ni.3829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haspeslagh E, Heyndrickx I, Hammad H, et al. The hygiene hypothesis: immunological mechanisms of airway tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol 2018;54:102–8. 10.1016/j.coi.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kramer MS, Guo T, Platt RW, et al. Does previous infection protect against atopic eczema and recurrent wheeze in infancy? Clin Exp Allergy 2004;34:753–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peebles RS. Viral infections, atopy, and asthma: is there a causal relationship? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113:S15–18. 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinez FD. Viruses and atopic sensitization in the first years of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:S95–9. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.supplement_2.ras-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nafstad P, Brunekreef B, Skrondal A, et al. Early respiratory infections, asthma, and allergy: 10-year follow-up of the Oslo birth cohort. Pediatrics 2005;116:e255–62. 10.1542/peds.2004-2785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dharmage SC, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, et al. Antibiotics and risk of asthma: a debate that is set to continue. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45:6–8. 10.1111/cea.12424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martorano LM, Grayson MH. Respiratory viral infections and atopic development: from possible mechanisms to advances in treatment. Eur J Immunol 2018;48:407–14. 10.1002/eji.201747052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheung DS, Ehlenbach SJ, Kitchens T, et al. Development of atopy by severe paramyxoviral infection in a mouse model. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;105:437–43. 10.1016/j.anai.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grunewald SM, Hahn C, Wohlleben G, et al. Infection with influenza A virus leads to flu antigen-induced cutaneous anaphylaxis in mice. J Invest Dermatol 2002;118:645–51. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Culley FJ, Pennycook AMJ, Tregoning JS, et al. Differential chemokine expression following respiratory virus infection reflects Th1- or Th2-biased immunopathology. J Virol 2006;80:4521–7. 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4521-4527.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-047768supp001.pdf (223.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.