Abstract

Intracranial abscesses are uncommon, serious and life-threatening infections. A brain abscess is caused by inflammation and collection of infected material, coming from local or remote infectious sources. Patients with chronic kidney disease on dialysis are prone to invasive bacterial infections like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) especially in the presence of central venous catheters or arteriovenous grafts. However, intracranial abscess formation due to MRSA is rare. Here, we present a case of MRSA brain abscess with an atypical clinical presentation in the absence of traditional risk factors.

Intracranial abscesses are uncommon, serious, and life-threatening infections. A Brain abscess is caused by inflammation and collection of infected material, coming from local or remote infectious sources. Patients with chronic kidney disease on dialysis are prone to invasive bacterial infections like methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) especially in the presence of central venous catheters or arterio-venous grafts. However intracranial abscess formation due to MRSA is rare. Here we present a case of MRSA brain abscess with an atypical clinical presentation in the absence of traditional risk factors. A 46-year-old male with chronic kidney disease (CKD) secondary to chronic glomerulonephritis, on haemodialysis for 4 years through a left brachio-cephalic AVF developed an episode of generalised tonic-clonic seizures lasting 2 min during his scheduled dialysis session. He reported no complaints before entry to the dialysis. On clinical examination, he was drowsy with the absence of any focal motor deficits. His blood pressure was recorded to be 200/120 mm Hg. He was managed in the intensive care unit with mechanical ventilation, intravenous nitroglycerine for blood pressure control, levetiracetam for seizures and empirical vancomycin. Radiological evaluation showed a brain abscess in the midline involving bosth basi-frontal lobes. After medical optimization, the abscess was drained surgically, and the pus cultured. As culture grew Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus, he was treated with intravenous vancomycin for 6 weeks. On follow up, the abscess had resolved and the patient recovered without any neurological deficits.

Keywords: chronic renal failure, dialysis, infection (neurology), neurosurgery

Background

Haemodialysis is now substantially safer than it was initially, and risks directly related to the dialysis procedure are rare.1 Infections are an important cause of morbidity and mortality for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD)2 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections are seen in haemodialysis patients commonly secondary to bloodstream invasion by indwelling central venous catheters or arteriovenous grafts (AVG).3 These may be easier to diagnose as patients present with features of sepsis in the setting of a central venous catheter (CVC) or AVG use. Patients also present with metastatic complications like endocarditis, osteomyelitis or meningitis.4 Intracranial abscesses in haemodialysis patients have rarely been reported in the literature.5 Moreover clinical presentation of patients with a state of immune dysfunction like ESKD may be atypical.6 We describe a case of an intracranial abscess due to MRSA in an ESKD patient on haemodialysis through an upper limb arteriovenous fistula (AVF) presenting with hypertension and seizures during a scheduled haemodialysis session. Intradialytic hypertension occurs when there is a paradoxical increase in blood pressure during or immediately after haemodialysis and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.7 8 Intradialytic seizure is an uncommon but serious complication. It may be a manifestation of disequilibrium syndrome, intradialytic hypertension leading to posterior reversible encephalopathy or a manifestation of a cerebrovascular accident affecting the cerebral cortex.9

Case presentation

A 46-year-old man with chronic kidney disease (CKD) secondary to chronic glomerulonephritis, on haemodialysis for 4 years through a left brachiocephalic AVF developed an episode of generalised tonic-clonic seizures lasting 2 min during his scheduled dialysis session. He reported no complaints before entry to the dialysis. On clinical examination, he was drowsy with the absence of any focal motor deficits. His blood pressure was recorded to be 200/120 mm Hg. He was managed in the intensive care unit with mechanical ventilation, intravenous nitroglycerine for blood pressure control and levetiracetam for seizures.

Investigations

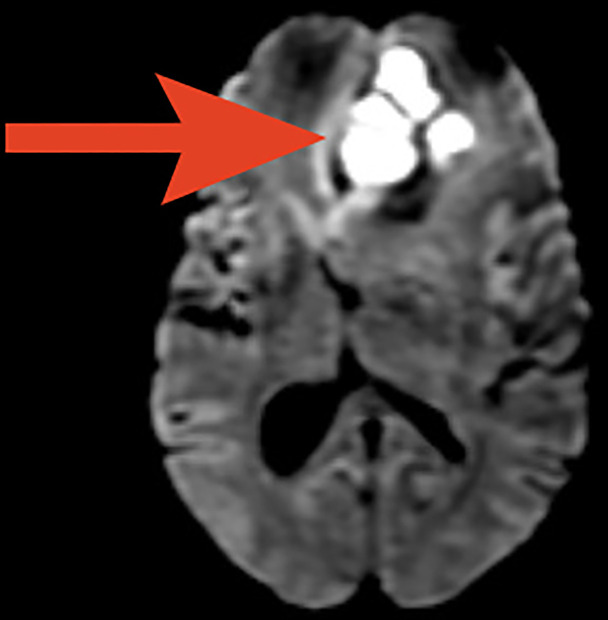

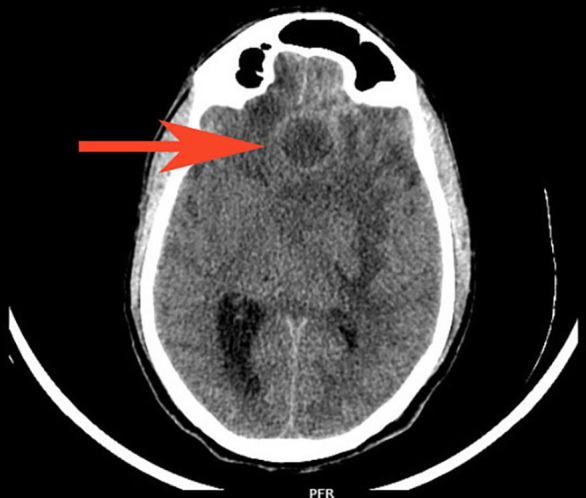

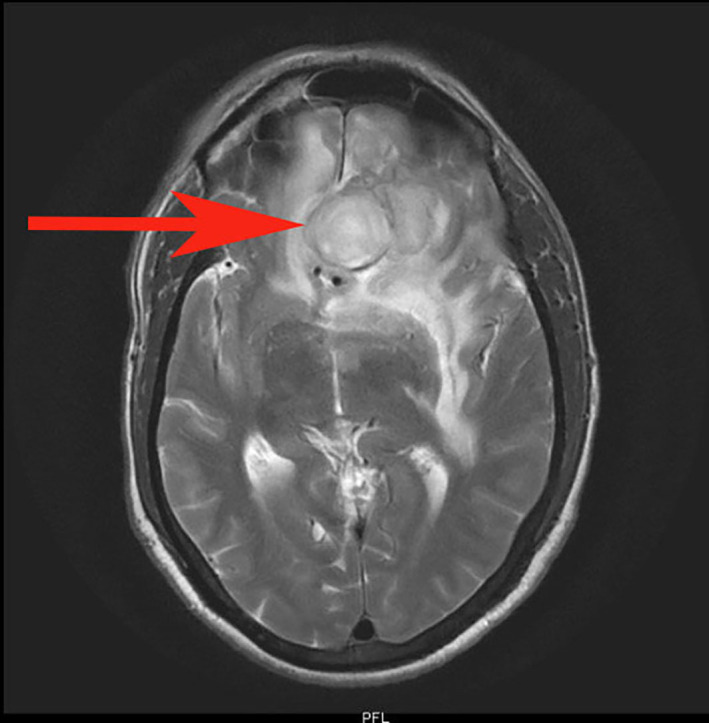

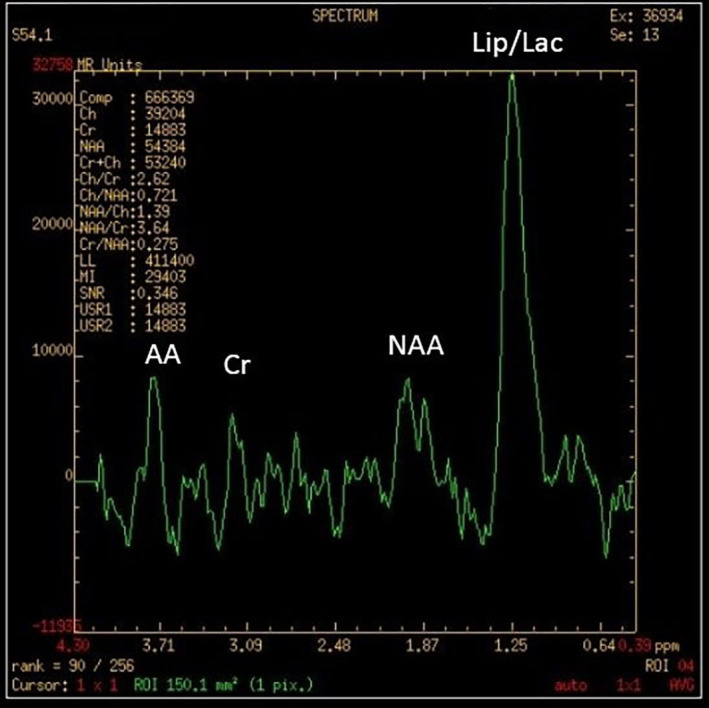

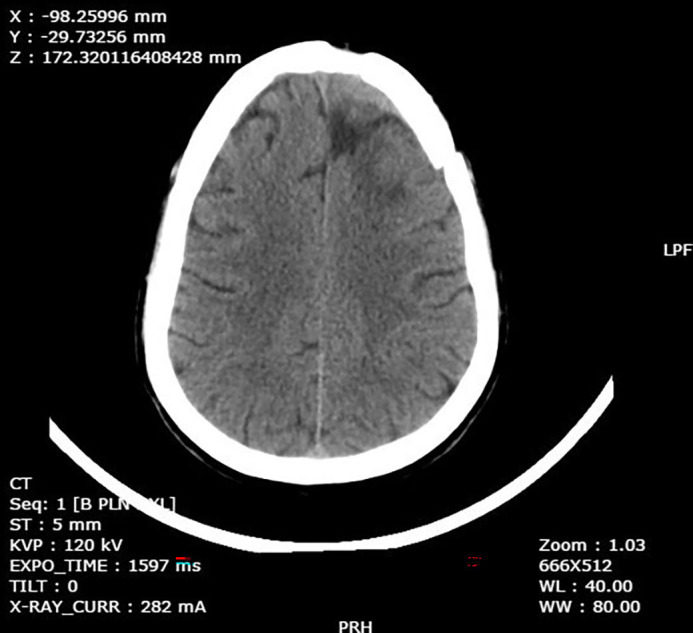

The metabolic panel was normal for electrolytes including calcium, magnesium, and ammonia. CT of the brain showed a well-defined rounded hypodense intra-axial lesion (~2.5×2.3×2.3 cm) (CC (craniocaudal)×TR (transverse)×AP (anteroposterior) with an isohyperdense rim in midline involving both the basifrontal lobes with mass effect (figure 1). MRI of the brain showed few conglomerated, altered-intensity lesions in the left basifrontal lobe with central diffusion restriction and significant perilesional oedema and mass effect (figures 2 and 3). An MRI with contrast was avoided as the patient had ESKD. Magnetic Resonance (MR) spectroscopy showed elevated lipid/lactate and amino acid peaks with reduced N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) levels and no choline peak within the lesion suggestive of a brain abscess (figure 4).

Figure 1.

CT brain showed a well-defined rounded hypodense intra-axial lesion of ~2.5×2.3 x2.3 cm (CC×TR×AP) with isohyperdense rim (red arrow) in the midline involving both the basifrontal lobes with mass effect in form effacement of frontal horn and body of left lateral ventricle, third ventricle and midline shift to right by 1.2 cm with subfalcine herniation and dilatation of right lateral ventricle. AP, Anterposterior; CC, Craniocaudal; PFR, Posterior Foot Right; TR: Transverse.

Figure 2.

T2-weighted axial MRI showing conglomerated altered intensity lesion (red arrow) of ~2.5×2.3×2.3 cm (CC×TR×AP) in the left basifrontal lobe. AP, Anterposterior; CC, Craniocaudal; PFR, Posterior Foot Right; TR: Transverse.

Figure 3.

Axial diffusion-weighted MRI showing central diffusion restriction in the area of the abscess (red arrow) with significant perilesional oedema and mass effect.

Figure 4.

MR spectroscopy showing elevated lipid/lactate (Lip/Lac) and amino acid (AA) peaks with reduced N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) levels and no choline peak within the lesion. Cr, creatinine.

Differential diagnosis

Based on the clinical presentation of a generalised tonic-clinic seizure with accelerated hypertension, a possibility of hypertensive encephalopathy or cerebrovascular accident was entertained. However, after obtaining a non-contrast CT of the brain, an intracranial space-occupying lesion was suspected, which could have been primary or secondary tumours, infections like tuberculoma or brain abscesses.

Treatment

On basis of the CT and MRI reports, a diagnosis of brain abscess was made. The patient was started on empirical vancomycin, following which he underwent an urgent craniotomy and abscess drainage. Pus and tissue cultures from the brain abscess grew MRSA. He received intravenous vancomycin for a total of 6 weeks. There was no evidence of infective endocarditis, middle ear infection or evidence of sinusitis. A dental evaluation was normal. At follow-up after 6 weeks, the patient was asymptomatic. A repeat CT brain showed gliotic changes in the same area (figure 5). The patient was continued on antiepileptics.

Figure 5.

Repeat CT after drainage and antibiotic treatment showing resolution at 6 weeks. KVP, Kilo Volt Power; PRH, Posterior Right Head; ST, Slice Thickness; WL, Window Length; WW, Window Width.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient recovered from this illness without any residual neurological deficits.

Discussion

Infections are the second most common cause for mortality in patients with CKD), cardiovascular causes being first.10–12 ESKD is a stage of acquired immunodeficiency due to alterations in both innate and adaptive immunity predisposing them to infections. Persistent low-grade inflammation is caused by disturbances of innate immunity due to inadequate monocyte and neutrophil function. Disturbances of the adaptive immune responses result in a decrease in antigen-presenting function, T-cell-mediated immune response and immunological memory13 14

S. aureus is—as for the general population15–17—the single leading pathogen causing severe infections in dialysis patients, responsible for 27%–39% of all bacteraemia in dialysis patients.16 18 The risk of invasive MRSA infection is 100 times greater in dialysis patients than in the general population19 20 However, the incidence of S. aureus causing brain abscess is rare. In a study by Lu et al, a high proportion (28.6%) of dialysis patients were found to have MRSA carriage and subsequently developed MRSA infections.21 According to a study by Bahubali et al of 21 subjects, the most common symptoms of an MRSA brain abscess are fever, followed by a headache. Focal neurological deficits were also noted in a few of the patients (visual deficits in two, hemiparesis in two, hemiplegia in two and ataxia in two). Isolated presentation with seizures is rare.22

Neuroimaging plays an important role in the diagnosis of brain abscess. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging are important modalities in the diagnosis of brain abscess.23 24 However, gadolinium-based scans are avoided in patients with end-stage renal disease due to the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.25 The role of H-MR (Proton (H) Magnetic Resonance) spectroscopy26 in establishing the diagnosis of an intracranial abscess and differentiating it from other look-alike ring-enhancing lesions has been adequately explored in the literature.27 28 However, the sensitivity and the specificity of 1 H-MR spectroscopy have not been established. Hence it is used only as adjunct modality rather than standard of care. In a study by Fountas et al, in metastatic tumours, there was a high concentration of choline but a total absence of phosphocreatine-creatinine (Pcr-Cr), NAA and lactate. Meningiomas showed a high concentration of choline, decreased Pcr-Cr and NAA, and the presence of lipids. Abscesses showed an absence of choline, Pcr-Cr NAA and by the presence of lipids and lactate. Succinate was not detected in any of these patients with cerebral abscesses.29 The presence of amino acids on in vivo H-MR spectroscopy is a sensitive marker of a pyogenic abscess, but its absence does not rule out a pyogenic aetiology. An anaerobic bacterial origin is signified by the presence of acetate with or without succinate.30

Management of a brain abscess usually requires a multidisciplinary and individualised approach31 with a combination of antibiotics and surgical drainage; the latter useful for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.24 There is no hard evidence that guides decision making on the modality of treatment based on the size of the abscess. However, a size >2.5 cm has been suggested as a cut-off to prompt a neurosurgical intervention.32 33 In addition, the presence of mass effect, impending brain herniation, lack of response to initial medical therapy and absence of any microbiological diagnosis to guide antibiotics, should prompt either a stereotactic aspiration or excision drainage.24

Most abscesses are treated with penicillin G (10–20 million units/day) along with chloramphenicol (3–4 g/day).34 However, the increasing emergence of infections with penicillin-resistant organisms has highly limited the usage of penicillin.35 Hence, a combination of metronidazole (0.5 g intravenous every 8 hours) and cefotaxime (3 g intravenous every 8 hours) is preferred due to their high penetration power, antimicrobial action (which is at par with chloramphenicol) and smaller side effect profile.36 However, in the case of S. aureus, vancomycin should be included until culture and susceptibility results are available. If it is methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, vancomycin should be discontinued and nafcillin or oxacillin should be started. In the case of MRSA, vancomycin (15–20 mg/kg ntravenous every 8–12 hours) should be continued.37 Linezolid (600 mg two times per day) along with rifampicin (600 mg daily) can also be used.38

The duration of antibiotics for brain abscesses is prolonged, usually 4–8 weeks.32 The duration of therapy should be guided by follow-up assessment of clinical course and imaging studies; antibiotic therapy is continued until there are a good clinical response and substantial improvement of imaging findings.39 Needle aspiration and surgical excision have both been used to treat brain abscesses and are also required for diagnosis, before the initiation of antibiotic therapy if possible. Needle aspiration is generally preferable to surgical excision as it is less invasive and thus reduces the neurological sequelae.40 41 A burr hole is placed and then needle aspiration is performed under CT or ultrasonography guidance42 The course of intravenous antibiotic therapy can be shortened to 4 weeks following excision compared with drainage. Excised lesions are less likely to relapse than lesions that have only been drained.43 The use of steroids as an adjunct to control the cerebral oedema caused by an abscess is controversial with some evidence to suggest decreased penetration of antibiotics through blood–brain barrier in addition to the risk of flaring up of the infection.24 A study by Maxwell et al, however, has found dexamethasone highly effective.44 45 A systematic review and meta-analysis showed no effect of dexamethasone on mortality in patients with brain abscess.46 Nevertheless, steroids are to be used prudently and are recommended perioperatively to avoid acute brain herniation in patients with signs of meningitis or disproportionate cytotoxic oedema.39 47

Brain abscess prognosis has significantly improved in the past couple of years, but patient monitoring is necessary considering potential long-term consequences and the risk of recidivism.48 According to available literature, the mortality rate is usually less than 15% without the data on the mortality rate of patients on dialysis.49

The novelty in our case was the atypical presentation of the patient with a hypertensive emergency with generalised tonic-clonic seizures, without features like fever, headache and focal neurological deficits. Intradialytic hypertension may have been a consequence of the seizure episode which may be due to stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system and release of catecholamines.50 Probably a net state of immunosuppression due to the uraemic state played a role in the suppression of symptoms. MR spectroscopy provided an important clue to the aetiology being infective. No obvious source for the metastatic infection could be identified. Despite comorbidities and having a higher risk of adverse outcomes, the patient recovered with no residual deficits or further seizures.51

Learning points.

Infections are an important cause of morbidity and mortality for patients with end-stage kidney disease.

Infections in patients with chronic kidney disease on haemodialysis may have atypical presentations.

In a patient on dialysis with a hypertensive emergency and seizures, a diagnosis of hypertensive encephalopathy should not be presumed and further evaluation with a CT imaging of the brain as a screening test may need to be done.

A high index of suspicion with a prompt investigation, treatment may make a difference in reducing morbidity or mortality.

Acknowledgments

Dr Srikanth Prasad, Registrar (former), Department of Nephrology, Kasturba Medical College Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education. Dr Girish Menon, Professor, Department of Neurosurgery, Kasturba Medical College Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education.

Footnotes

Twitter: @shraddha158

Contributors: The case discussed in this report is of a patient who was attended by SM as an intern in Kasturba Medical College Manipal, under the direct supervision of SVS, Assistant Professor, Department of Nephrology, Kasturba Medical College Manipal. The patient was admitted under the care of RAP, Professor, Department of Nephrology, who also oversaw patient care and treatment. SPN is Professor and Head of Department of Nephrology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal who consulted in the process of treatment.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA. Hemodialysis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2010;363:1833–45. 10.1056/NEJMra0902710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mix T-CH, St peter WL, Ebben J, et al. Hospitalization during advancing chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;42:972–81. 10.1016/j.ajkd.2003.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasch O, Ayats J, Angeles Dominguez M. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infection: secular trends over 19 years at a university hospital. Med 2011;90:319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Friedman JY, O'Neal BF, O’Neal BF, et al. Outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus infection in hemodialysis-dependent patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:428–34. 10.2215/CJN.03760708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barczyk MP, Łebkowski WJ, Mariak Z, et al. Brain abscess as a rare complication in a hemodialysed patient. Med Sci Monit 2001;7:1329–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syed-Ahmed M, Narayanan M. Immune dysfunction and risk of infection in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2019;26:8–15. 10.1053/j.ackd.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.K/DOQI Workgroup . K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;45:S49–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park J, Rhee CM, Sim JJ, et al. A comparative effectiveness research study of the change in blood pressure during hemodialysis treatment and survival. Kidney Int 2013;84:795–802. 10.1038/ki.2013.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabbari B, Vaziri ND. The nature, consequences, and management of neurological disorders in chronic kidney disease. Hemodial Int 2018;22:150–60. 10.1111/hdi.12587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davenport A. Intradialytic complications during hemodialysis. Hemodial Int 2006;10:162–7. 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2006.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pendse S, Singh AK. Complications of chronic kidney disease: anemia, mineral metabolism, and cardiovascular disease. Med Clin North Am 2005;89:549–61. 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murabito S, Hallmark BF. Complications of kidney disease. Nursing Clinics of North America 2018;53:579–88. 10.1016/j.cnur.2018.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato S, Chmielewski M, Honda H, et al. Aspects of immune dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:1526–33. 10.2215/CJN.00950208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoen B, Paul-Dauphin A, Hestin D, et al. EPIBACDIAL: a multicenter prospective study of risk factors for bacteremia in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:869–76. 10.1681/ASN.V95869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang F-Y, MacDonald BB, Peacock JE, et al. A prospective multicenter study of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: incidence of endocarditis, risk factors for mortality, and clinical impact of methicillin resistance. Medicine 2003;82:322–32. 10.1097/01.md.0000091185.93122.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaller MA, Jones RN, Doern GV, et al. Bacterial pathogens isolated from patients with bloodstream infection: frequencies of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (United States and Canada, 1997). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998;42:1762–70. 10.1128/AAC.42.7.1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mylotte JM, Tayara A. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: predictors of 30-day mortality in a large cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:1170–4. 10.1086/317421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowler VG, Olsen MK, Corey GR, et al. Clinical identifiers of complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2066–72. 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among dialysis patients--United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:197–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh K, Raju V, Nikalji R, et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Patients With Renal Disorders: A Review. World J Nephrol Urol 2019;8:8–13. 10.14740/wjnu384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu P-L, Chin L-C, Peng C-F, et al. Risk factors and molecular analysis of community methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:132–9. 10.1128/JCM.43.1.132-139.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahubali VKH, Vijayan P, Bhandari V, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus intracranial abscess: An analytical series and review on molecular, surgical and medical aspects. Indian J Med Microbiol 2018;36:97–103. 10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_17_41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy JS, Mishra AM, Behari S, et al. The role of diffusion-weighted imaging in the differential diagnosis of intracranial cystic mass lesions: a report of 147 lesions. Surg Neurol 2006;66:246–50. 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, McKhann GM, et al. Brain abscess. N Engl J Med 2014;371:447–56. 10.1056/NEJMra1301635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyd AS, Zic JA, Abraham JL. Gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:27–30. 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pal D, Bhattacharyya A, Husain M, et al. In vivo proton MR spectroscopy evaluation of pyogenic brain abscesses: a report of 194 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31:360–6. 10.3174/ajnr.A1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai PH, Ho JT, Chen WL, et al. Brain abscess and necrotic brain tumor: discrimination with proton MR spectroscopy and diffusion-weighted imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:1369–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapsalaki EZ, Gotsis ED, Fountas KN. The role of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the diagnosis and categorization of cerebral abscesses. Neurosurg Focus 2008;24:E7. 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/6/E7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Gotsis SD, et al. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of brain tumors. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2000;74:83–94. 10.1159/000056467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg M, Gupta RK, Husain M, et al. Brain abscesses: etiologic categorization with in vivo proton MR spectroscopy. Radiology 2004;230:519–27. 10.1148/radiol.2302021317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvis Miranda H, Castellar-Leones SM, Elzain MA, et al. Brain abscess: current management. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2013;4:S67–81. 10.4103/0976-3147.116472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arlotti M, Grossi P, Pea F, et al. Consensus document on controversial issues for the treatment of infections of the central nervous system: bacterial brain abscesses. Int J Infect Dis 2010;14 Suppl 4:S79–92. 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mamelak AN, Mampalam TJ, Obana WG, et al. Improved management of multiple brain abscesses: a combined surgical and medical approach. Neurosurgery 1995;36:76–86. 10.1227/00006123-199501000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Infection in Neurosurgery Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy . The rational use of antibiotics in the treatment of brain abscess. Br J Neurosurg 2000;14:525–30. 10.1080/02688690020005527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brook I. Microbiology and treatment of brain abscess. J Clin Neurosci 2017;38:8–12. 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lonsdale DO, Udy AA, Roberts JA, et al. Antibacterial therapeutic drug monitoring in cerebrospinal fluid: difficulty in achieving adequate drug concentrations. J Neurosurg 2013;118:297–301. 10.3171/2012.10.JNS12883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:e18–55. 10.1093/cid/ciq146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito N, Aoki K, Sakurai T, et al. Linezolid treatment for intracranial abscesses caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus--two case reports. Neurol Med Chir 2010;50:515–7. 10.2176/nmc.50.515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muzumdar D, Jhawar S, Goel A. Brain abscess: an overview. Int J Surg 2011;9:136–44. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratnaike TE, Das S, Gregson BA, et al. A review of brain abscess surgical treatment--78 years: aspiration versus excision. World Neurosurg 2011;76:431–6. 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.03.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meng X-H, Feng S-Y, Chen X-L, et al. Minimally invasive image-guided keyhole aspiration of cerebral abscesses. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng PY, Seow WT, Ong PL. Brain abscesses: review of 30 cases treated with surgery. Aust N Z J Surg 1995;65:664. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1995.tb00677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mampalam TJ, Rosenblum ML. Trends in the management of bacterial brain abscesses: a review of 102 cases over 17 years. Neurosurgery 1988;23:451–8. 10.1227/00006123-198810000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maxwell RE, Long DM, French LA. The Clinical Effects of a Synthetic Gluco-Corticoid used for Brain Edema in the Practice of Neurosurgery. In: Reulen HJ, Schürmann K, eds. Steroids and brain edema. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wallenfang T, Reulen HJ, Schürmann K. Clinical Use of Steroids in Cerebral Abscesses. In: Hartmann A, Brock M, eds. Treatment of cerebral edema. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simjian T, Muskens IS, Lamba N, et al. Dexamethasone Administration and Mortality in Patients with Brain Abscess: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2018;115:257–63. 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee T-H, Chang W-N, Su T-M, et al. Clinical features and predictive factors of intraventricular rupture in patients who have bacterial brain abscesses. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:303–9. 10.1136/jnnp.2006.097808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel K, Clifford DB. Bacterial brain abscess. Neurohospitalist 2014;4:196–204. 10.1177/1941874414540684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bokhari MR, Mesfin FB. Brain abscess. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simon RP, Aminoff MJ, Benowitz NL. Changes in plasma catecholamines after tonic-clonic seizures. Neurology 1984;34:255–7. 10.1212/WNL.34.2.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menon S, Bharadwaj R, Chowdhary A, et al. Current epidemiology of intracranial abscesses: a prospective 5 year study. J Med Microbiol 2008;57:1259–68. 10.1099/jmm.0.47814-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]