Abstract

Objectives

To report the impact of burosumab on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and ambulatory function in adults with X-linked hypophosphataemia (XLH) through 96 weeks.

Methods

Adults diagnosed with XLH were randomised 1:1 in a double-blinded trial to receive subcutaneous burosumab 1 mg/kg or placebo every 4 weeks for 24 weeks (NCT02526160). Thereafter, all subjects received burosumab every 4 weeks until week 96. PROs were measured using the Western Ontario and the McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) and Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), and ambulatory function was measured with the 6 min walk test (6MWT).

Results

Subjects (N=134) were randomised to burosumab (n=68) or placebo (n=66) for 24 weeks. At baseline, subjects experienced pain, stiffness, and impaired physical and ambulatory function. At week 24, subjects receiving burosumab achieved statistically significant improvement in some BPI-SF scores, BFI worst fatigue (average and greatest) and WOMAC stiffness. At week 48, all WOMAC and BPI-SF scores achieved statistically significant improvement, with some WOMAC and BFI scores achieving meaningful and significant change from baseline. At week 96, all WOMAC, BPI-SF and BFI achieved statistically significant improvement, with selected scores in all measures also achieving meaningful change. Improvement in 6MWT distance and percent predicted were statistically significant at all time points from 24 weeks.

Conclusions

Adults with XLH have substantial burden of disease as assessed by PROs and 6MWT. Burosumab treatment improved phosphate homoeostasis and was associated with a steady and consistent improvement in PROs and ambulatory function.

Trial registration number

Keywords: therapeutics, patient reported outcome measures, outcome assessment, healthcare

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

In a phase 3 trial, burosumab significantly increased serum phosphate concentrations compared with placebo over 24 weeks, with a sustained effect on phosphate homoeostasis over time, and significantly improved patient-reported outcomes (PROs) from baseline to 48 weeks.

What does this study add?

We further characterise the cumulative symptom burden of X-linked hypophosphataemia (XLH), showing that adults with XLH experience substantial pain, stiffness, fatigue and impairment in physical and ambulatory function.

Rapid and persistent improvements in phosphate homoeostasis with burosumab treatment are associated with a consistent reduction in the burden of disease associated with XLH, with statistically significant improvements from baseline in PROs and ambulatory function seen as early as week 24 and at week 96, achieving meaningful change from baseline in some pain, stiffness and fatigue scores.

How might this impact on clinical practice or further developments?

The sustained positive outcomes over time indicate that, despite the long-term cumulative complications and physical impairments associated with XLH, burosumab improves symptoms that are clinically meaningful to adults with XLH, suggesting a role for long-term use of burosumab in improving physical function and quality of life.

Introduction

X-linked hypophosphataemia (XLH) is a rare, genetic, progressive, lifelong phosphate wasting disease caused by loss-of-function mutations in the PHEX gene (phosphate-regulating endopeptidase homologue, X-linked), which results in excess circulating levels of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23).1 2 The resultant chronic hypophosphataemia and osteomalacia in combination with the irreversible skeletal deformities acquired in childhood are associated with morbidities that develop and progress in adulthood, including osteoarthritis, enthesopathies, fractures, pseudofractures and spinal stenosis,3–5 causing bone and joint pain, stiffness, impaired mobility and diminished physical function. These morbidities ultimately decrease health-related quality of life, limit activities of daily living and have a negative psychosocial impact.5–10

Until recently, the only treatment for XLH has been conventional therapy with oral phosphate replacement combined with active vitamin D. Relief of bone pain and healing of pseudofractures has been described in a small number of cases in a non-interventional study.11 However, due to the lack of robust trial data evaluating the efficacy of treatment with conventional therapy in adults, along with the known risks of treatment, a frequent practice has been to treat all children but only treat symptomatic adults.12 In a multinational, online survey 49% of adults with XLH were being treated with oral phosphate and 64% with active vitamin D metabolites, with 47% receiving both.5

Burosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds to excess circulating FGF23 and directly inhibits its activity, thereby correcting the aberrant phosphate homoeostasis in adults with XLH. The efficacy of burosumab has been demonstrated in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial with open-label extension in adults with XLH.13 14 The primary endpoint analysis demonstrated a statistically significant effect of burosumab relative to placebo in increasing serum phosphate concentrations from baseline to week 24.14 Results from the treatment continuation period with all subjects receiving burosumab demonstrated that the effect of burosumab to improve phosphate homoeostasis was sustained over 48 weeks.13

Reporting of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and ambulatory function was limited to the three key secondary endpoints (Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) worst pain, Western Ontario and the McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function subscale, WOMAC stiffness subscale) and one exploratory endpoint (change from baseline in 6 min walk test (6MWT) distance walked) in the week 24 and week 48 analyses.13 14 Burosumab was associated with improvement in the four patient-relevant endpoints when compared with the placebo-treated group at week 24, however, with Hochberg multiplicity adjustment, only the difference in reduction in WOMAC stiffness was significant between treatments (p=0.012).14 Portale et al13 reported that in both groups, burosumab was associated with clinically significant and sustained improvement from baseline to week 48 in scores for the same four patient-relevant endpoints (p<0.001).

To extend the initial report of the impact of burosumab on PROs and ambulatory function in adults with XLH, we report a change from baseline analysis through week 96 on a wider range of PRO endpoints, using WOMAC, BPI-SF, Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) and ambulatory function according to 6MWT, and assess if the change reaches XLH-specific meaningful change benchmarks.

Methods

Design

The design of this international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study (NCT02526160) has been reported elsewhere and is only briefly described here.13 14

Patient and public involvement

Data collected from adults with XLH via an online survey and through interviews provided insights that informed the decision of which PRO measures to include in the clinical trial.5 6 The XLH Network, a patient advocacy group, was consulted in the development of the survey questions. These data indicated that pain, stiffness and impaired physical function and mobility were substantial issues for adults with XLH, and that the BPI-SF and WOMAC were appropriate to measure deficits. As a result, the decision was made for BPI-SF worst pain score, WOMAC stiffness and WOMAC physical function to be key secondary efficacy endpoints.

Focus groups, in collaboration with The XLH Network, were held with adults with XLH to solicit input regarding the proposed duration of the study, number of site visits required, travel requirements and perceived burden of the assessments to be performed. The XLH Network also distributed recruitment materials to their members to increase awareness of the study. The results of the study were presented by physician speakers to the patient community at The XLH Network events.

Participants

Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in Insogna et al.14 Major inclusion criteria were adults (18–65 years old) with a confirmed diagnosis of XLH, biochemical findings consistent with XLH, and the presence of skeletal pain attributed to XLH or osteomalacia. Major exclusion criteria included recent history of traumatic fracture or orthopaedic surgery. For adults receiving therapies affecting phosphate metabolism, these therapies must have been stopped prior to enrolment. Subjects were characterised according to enthesopathies, osteoarthritis, pseudofractures and use of opioids or pain medication at baseline.14

Treatment groups

Eligible subjects were randomised 1:1 to receive burosumab (1.0 mg/kg) or placebo administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks for 24 weeks in a double-blinded trial. Thereafter, all subjects entered an open-label treatment continuation period for a further 24 weeks and received burosumab (1.0 mg/kg every 4 weeks). Subjects continued to receive burosumab for an additional 48 weeks during the open-label treatment extension period until week 96.

Subjects randomised to burosumab are referred to as the burosumab–burosumab group, and those randomised to placebo as the placebo–burosumab group. Subjects remained blinded to their original treatment assignment throughout the first 48 weeks of the study.

PROs and ambulatory function endpoints

The objective of the present analysis was to evaluate the effect of burosumab on physical function, stiffness, pain and fatigue (at week 24, 48 and 96; secondary endpoints), and ambulatory function (at week 24, 48 and 72; exploratory endpoint) compared with baseline.

The WOMAC index, BPI-SF and BFI were used for PRO assessments. The WOMAC index, completed at on-site study visits, is a self-reported questionnaire designed to assess pain, stiffness and physical function in subjects with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip, and has been validated in XLH.15 16 The BPI-SF is a self-reported, pain-specific questionnaire measuring pain severity and interference that has been validated in XLH.17 18 Subjects completed all BPI-SF items at the study visit on the day of treatment administration; additionally, subjects also completed the four BPI-SF pain severity items daily in a written diary to more fully characterise pain variability. The BFI is a self-reported, fatigue-specific questionnaire measuring fatigue severity and interference that has been validated in XLH.19 20 Subjects completed the three BFI fatigue severity items in a daily diary and completed the full instrument at the study visit. WOMAC, BPI-SF and BFI endpoints were prespecified, with the exceptions of WOMAC total score, BPI worst pain (greatest), BFI worst fatigue (greatest) and BFI fatigue interference, all of which were post hoc. Table 1 summarises how the score for each PRO instrument was determined in this analysis, including how to interpret XLH-specific meaningful change.21

Table 1.

Patient-reported instruments used in the clinical trial

| Feature | WOMAC15 | BPI-SF18 | BFI19 |

| Number of items | 24 | 15* | 9 |

| Response format | 5-point scale: none, mild, moderate, severe, extreme | 0–10 numerical rating scale (10 indicates worst pain severity/interference) | 0–10 numerical rating scale (10 indicates worst fatigue severity/interference) |

| Scores reported (number of items) | Pain (n=5) Stiffness (n=2) Physical function (n=17) Total score (n=24) |

Worst pain (average) (n=1)† Worst pain (greatest) (n=1)† Pain severity (n=4) Pain interference (n=7) |

Worst fatigue (average) (n=1)‡ Worst fatigue (greatest) (n=1)‡ Fatigue severity (n=3) Fatigue interference (n=6) Global fatigue (n=9) |

| Recall period | 48 hours | 24 hours | 24 hours |

| XLH-specific meaningful change (MCIDs)§ | ≥−10.0 total score ≥−11.0 pain ≥−10.0 stiffness ≥−8.0 physical function16 |

≥−1.72 worst pain ≥−1.0 pain interference17 |

≥−1.5 worst fatigue ≥−1.2 global fatigue ≥−1.2 fatigue interference20 |

*BPI-SF has 15 items in total, 11 items contribute to the scores reported in this analysis.

†BPI-SF question 3 asks subjects to rate their pain at its worst in the last 24 hours on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as you can imagine). This study reports worst pain (average score for question 3 over 8 days) and worst pain (greatest score for question 3 over 8 days).18 27 28

‡BFI question 3 asks subjects to rate their fatigue at its worst in the last 24 hours on a scale of 0 (no fatigue) to 10 (fatigue as bad as you can imagine). This study reports worst fatigue (average score over 8 days) and worst fatigue (greatest score over 8 days).19

§A guide for interpreting the mean in a group of subjects rather than a change in an individual.21

BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; WOMAC, Western Ontario and the McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; XLH, X-linked hypophosphataemia.

The 6MWT, used to assess ambulatory function, was administered by a trained clinician in accordance with principles set out in the American Thoracic Society guidelines.22 Subjects were instructed to walk the length of a premeasured course for six consecutive minutes. The total distance walked was recorded in metres; the percent predicted value for the 6MWT was calculated using published normative data based on age, sex and height.23 Here, we report the prespecified endpoints of 6MWT distance walked and 6MWT percent predicted for age and gender.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted for all randomised subjects who received at least one dose of either placebo or burosumab. Continuous variables are summarised using the mean (SD) and categorical variables using number and percentage of subjects. Baseline impairment is described at the item level for all PRO instruments, and the use and type of pain medication being taken at baseline was recorded in subjects’ pain medication diaries.

For the change from baseline analysis, secondary and exploratory endpoints were analysed at a significance level of 5% using a generalised estimating equations (GEE) repeated-measures analysis. Treatment visit and treatment-by-visit interaction were included as categorical variables. Baseline stratification was performed for BPI average pain (>6.0, ≤6.0). The GEE model was applied through week 96 for PRO endpoints and week 72 for 6MWT; the model included p value assessment for within-group change from baseline. Data are presented as least squares mean (SE) change from baseline. Missing data were handled according to the guidelines for each of the three questionnaires and the 6MWT. SAS V.9.4 or higher (SAS Institute) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

In total, 163 subjects were screened, and 134 were enrolled and randomised to burosumab (n=68) or placebo (n=66), with 133 subjects completing the placebo-controlled period; 126 subjects (94.0%) completed week 48 of the treatment continuation period and entered the open-label treatment extension period13; and 119 subjects (88.8%) completed the treatment extension period (48–96 weeks). All 134 subjects were included in the present analysis of PROs and ambulatory function.

Mean (SE) exposure to burosumab was 771 (22) days (range 167–957) for the burosumab–burosumab group and 626 (19) days (range 165–844) in the placebo–burosumab group.

Overall, the demographics were similar between treatment groups, as well as between subjects who completed the treatment extension period (n=119) and the total cohort enrolled (N=134) (table 2).

Table 2.

Patient baseline characteristics and patient-reported outcome and ambulatory function scores at baseline

| Characteristic/outcome | Burosumab (n=68) | Placebo (n=66) | Total cohort (N=134) | Treatment extension cohort (n=119)* |

| Baseline characteristic | ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 41.3 (11.6) | 38.7 (12.8) | 40.0 (12.2) | 40.5 (12.2) |

| Range | 20.0–63.4 | 18.5–65.5 | 18.5–65.5 | 18.5–65.5 |

| Female, n (%) | 44 (64.7) | 43 (65.2) | 87 (64.9) | 77 (64.7) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||||

| North America/Europe | 58 (85.3) | 58 (87.9) | 116 (86.6) | 101 (84.9) |

| Asia | 6 (8.8) | 5 (7.6) | 18 (13.4) | 18 (15.1) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD)† | 152.2 (9.5) | 152.7 (11.8) | 152.4 (10.7) | 152.1 (11.0) |

| BMI, mean (SD)† | 30.0 (7.5) | 30.6 (7.8) | 30.3 (7.6) | 30.6 (7.8) |

| Serum phosphate (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.3) |

| WOMAC, mean (SD) | ||||

| Total score | 51.8 (18.3) | 46.2 (17.7) | 49.1 (18.2) | 49.2 (18.4) |

| Physical functioning | 50.8 (19.7) | 43.9 (19.9) | 47.4 (20.0) | 47.6 (20.3) |

| Stiffness | 64.7 (20.3) | 61.4 (20.8) | 63.1 (20.5) | 62.6 (20.8) |

| Pain | 50.7 (18.0) | 48.0 (15.5) | 49.3 (16.8) | 49.3 (16.8) |

| Pain scores | ||||

| BPI-SF worst pain (average) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.8 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.4) |

| ≤6.0, n (%) | 15 (22.1) | 23 (34.8) | 38 (28.4) | 33 (27.7) |

| >6.0, n (%) | 53 (77.9) | 43 (65.2) | 96 (71.6) | 86 (72.3) |

| BPI-SF worst pain (greatest) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.1 (1.2) | 8.0 (1.5) | 8.0 (1.3) | 8.0 (1.3) |

| BPI-SF pain interference, mean (SD) | 5.2 (2.2) | 4.8 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.2) | 5.1 (2.2) |

| Any pain medication use, n (%) | 47 (69.1) | 44 (66.7) | 91 (67.9) | 81 (68.1) |

| Opioid use, n (%) | 17 (25.0) | 13 (19.7) | 30 (22.4) | 26 (21.8) |

| Fatigue scores, mean (SD) | ||||

| BFI global fatigue | 5.4 (2.0) | 4.9 (1.9) | 5.1 (2.0) | 5.1 (2.0) |

| BFI worst fatigue (average) | 6.9 (1.7) | 6.7 (1.5) | 6.8 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.6) |

| BFI worst fatigue (greatest) | 8.2 (1.4) | 8.2 (1.3) | 8.2 (1.3) | 8.2 (1.4) |

| BFI fatigue interference | 5.0 (2.3) | 4.5 (2.3) | 4.8 (2.3) | 4.8 (2.3) |

| Ambulatory function, mean (SD) | ||||

| 6MWT distance walked, m | 356.8 (109.5) | 367.4 (103.4) | 362.0 (106.3) | 358.9 (108.3) |

| 6MWT percentage predicted distance, % | 51.4 (15.8) | 52.3 (14.9) | 51.8 (15.3) | 51.5 (15.7) |

WOMAC range, 0–100, where 0 represents best health; BPI-SF range, 0–10, with 10 indicating worst pain; BFI range, 0–10, with 10 indicating worst fatigue.

*Subjects who completed the 96-week study extension period.

†Height and BMI were not recorded at baseline for one participant in each group.

6MWT, 6 min walk test; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; BMI, body mass index; BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; WOMAC, Western Ontario and the McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Baseline impairment

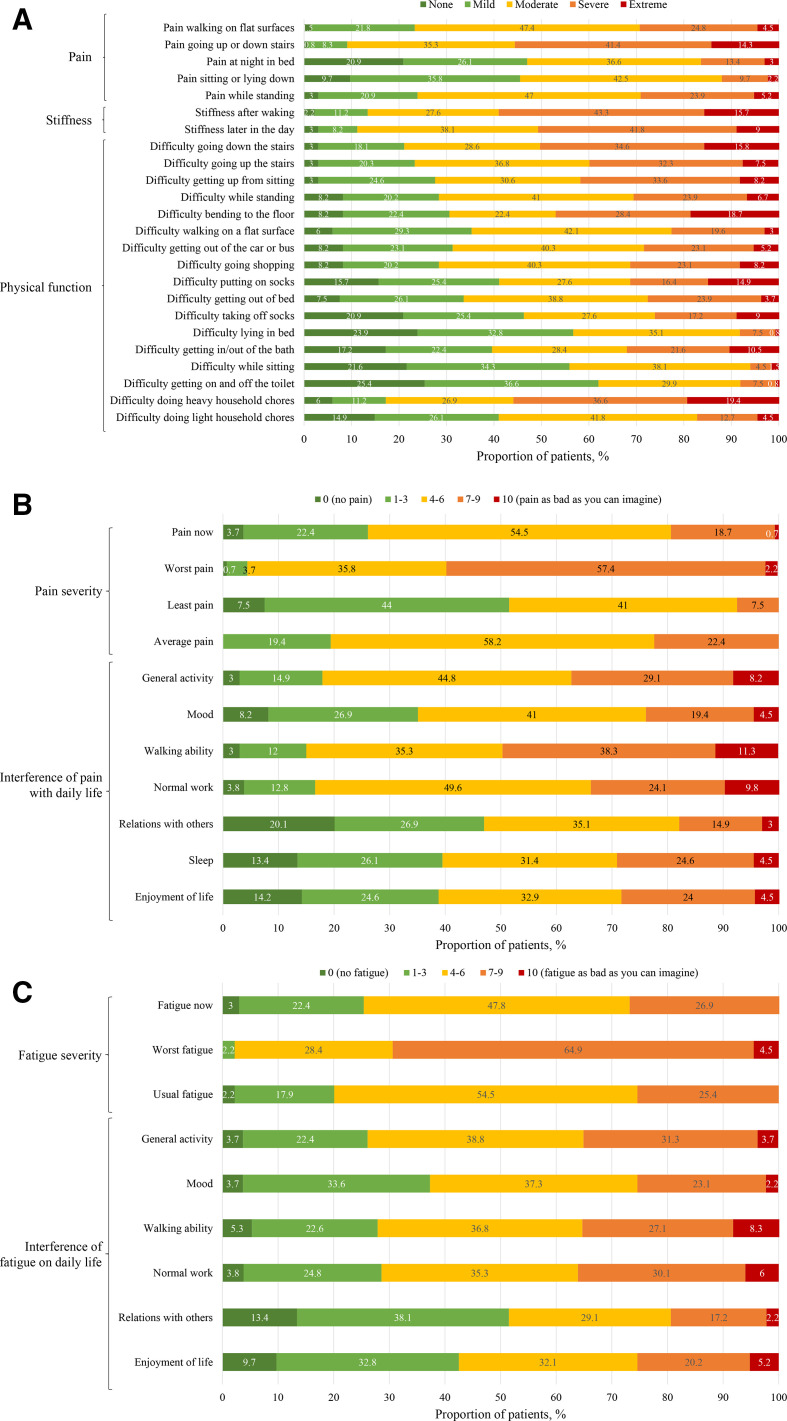

At baseline, subjects reported impairment in WOMAC total, physical function, stiffness and pain scores (table 2). Subjects reported notable difficulty going down stairs (50.4% had severe/extreme impairment) and doing heavy household chores (56.0% (severe/extreme)) with stiffness after waking (59% (severe/extreme)) and pain when going up or down stairs (55.6% (severe/extreme)) (figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Proportion of adults reporting (A) WOMAC, (B) BPI-SF and (C) BFI item level scores at baseline (N=134). Interference of pain on walking ability and normal work were not recorded at baseline for one participant in each group. BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; WOMAC, Western Ontario and the McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis.

Subjects reported pain and pain interference at baseline, with most subjects (71.6%) having a baseline BPI-SF worst pain (average) score >6.0 (severe) (table 2). The BPI-SF pain interference score showed moderate disruption in activities of daily living due to pain; severe pain when walking, during general activity and during normal work completely interfered with daily life for 11.2%, 8.2% and 9.7% of subjects, respectively (figure 1B).

Subjects reported mean worst fatigue (average) score >6.0 at baseline (table 2). The greatest overall impact was reported for the BFI interference items of walking ability, normal work and enjoyment of life, with the highest fatigue interference scores observed in walking ability (8.3% reported complete interference with daily living) (figure 1C).

Mean 6MWT distance walked was approximately half of the predicted distance based on age and sex, indicating impaired ambulation at baseline (table 2).

Change from baseline

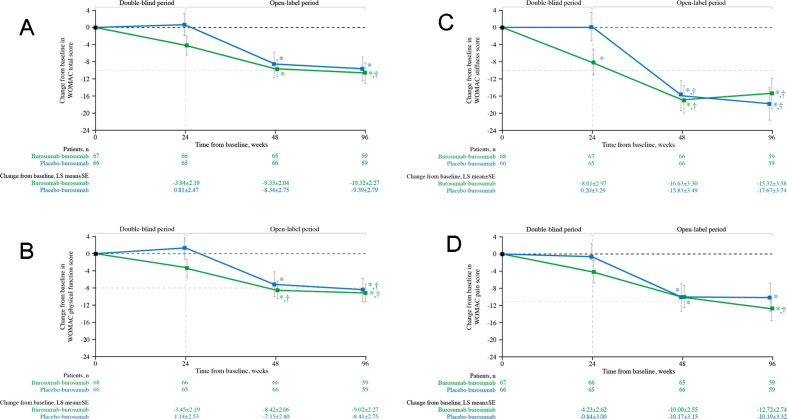

Subjects randomised to receive burosumab in the double-blind period had statistically significant improvements from baseline WOMAC stiffness scores at week 24 (p=0.007; figure 2C). At week 48, after the placebo group had been crossed over to receive burosumab for 24 weeks, the burosumab–burosumab and placebo–burosumab groups had significant improvements from baseline for all WOMAC scores (total score, figure 2A; physical function, figure 2B; stiffness, figure 2C and pain, figure 2D; all p<0.05); similarly at week 96, significant improvements from baseline were evident for all WOMAC scores (all p<0.05). Meaningful change was achieved for WOMAC stiffness in both treatment groups at weeks 48 and 96. For WOMAC physical function, meaningful change was achieved in the burosumab–burosumab group at week 48 and in both treatment arms at week 96. Meaningful change (see table 1 for definition) was also achieved at week 96 in the burosumab–burosumab group for WOMAC total score and WOMAC pain.

Figure 2.

Change from baseline in WOMAC (A) total score, and (B) physical function, (C) stiffness and (D) pain scores (N=134). Data show LS mean (±SE); lower scores indicate better health. *p<0.05 for LS mean change from baseline. †Indicates the minimal clinically important differences from baseline (≥−10.0 total score, ≥−8.0 physical function, ≥−10.0 stiffness, ≥−11.0 pain, shown by the pale grey horizontal line). LS, least squares; WOMAC, Western Ontario and the McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis.

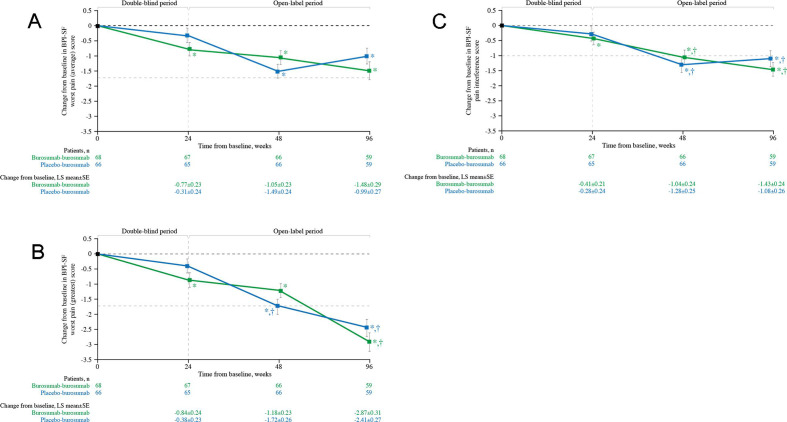

Subjects randomised to burosumab had significant improvements from baseline at week 24 in BPI-SF worst pain (average) (p<0.001; figure 3A), BPI-SF worst pain (greatest) (p<0.001; figure 3B) and BPI-SF pain interference (p=0.05; figure 3C). At weeks 48 and 96, improvements from baseline were significant for the burosumab–burosumab and placebo–burosumab groups for all BPI-SF scores (figure 3A–C; all p<0.001). Meaningful change was achieved for worst pain (greatest) in the placebo–burosumab group at week 48 and in both groups at week 96 (figure 3B). For pain interference, meaningful change was achieved in both treatment groups at weeks 48 and 96 (figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Change from baseline in BPI-SF (A) worst pain (average), (B) worst pain (greatest) and (C) pain interference scores (N=134). Data show LS mean (±SE); lower scores indicate lower pain severity and less pain interference. *p<0.05 for LS mean change from baseline. †Indicates minimal clinically important differences from baseline (≥−1.72 worst pain (average, greatest), ≥−1.0 pain interference, shown by the pale grey horizontal line). BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; LS, least squares.

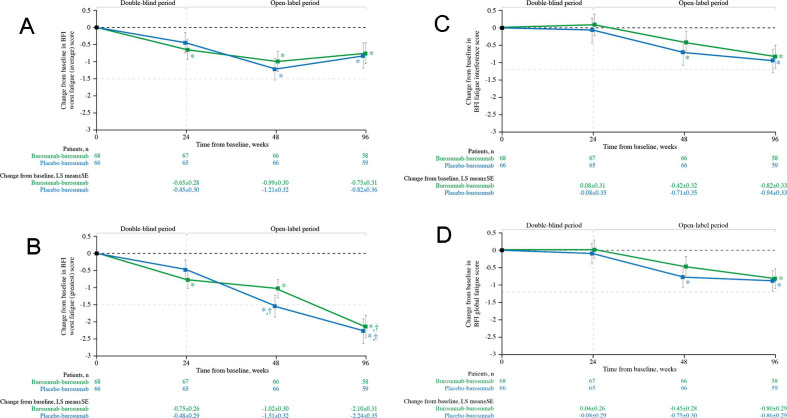

Subjects randomised to burosumab had significant improvements from baseline at week 24 in BFI worst fatigue (average) (p=0.020; figure 4A) and BFI worst fatigue (greatest) (p=0.004; figure 4B). At week 48, improvements from baseline in worst fatigue (average and greatest) were significant for the burosumab–burosumab and placebo–burosumab groups (both p<0.001; figure 4A and B); for fatigue interference and global fatigue, significant improvements were observed in the placebo–burosumab group at week 48 (all p<0.05; figure 4C and D). At week 96, significant improvement was observed for all fatigue parameters in both groups (all p<0.05). Meaningful change from baseline was achieved for BFI worst fatigue (greatest) at week 48 in the placebo–burosumab group and at week 96 in both groups.

Figure 4.

Change from baseline in BFI (A) worst fatigue (average), (B) worst fatigue (greatest), (C) global fatigue and (D) fatigue interference scores (N=134). Data show LS mean (±SE); lower scores indicate lower fatigue severity and less fatigue interference. *p<0.05 for LS mean change from baseline. †Indicates the minimal clinically important difference from baseline (≥−1.5 worst fatigue (average, greatest), ≥−1.2 global fatigue, ≥−1.2 fatigue interference, shown by the pale grey horizontal line). BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; LS, least squares.

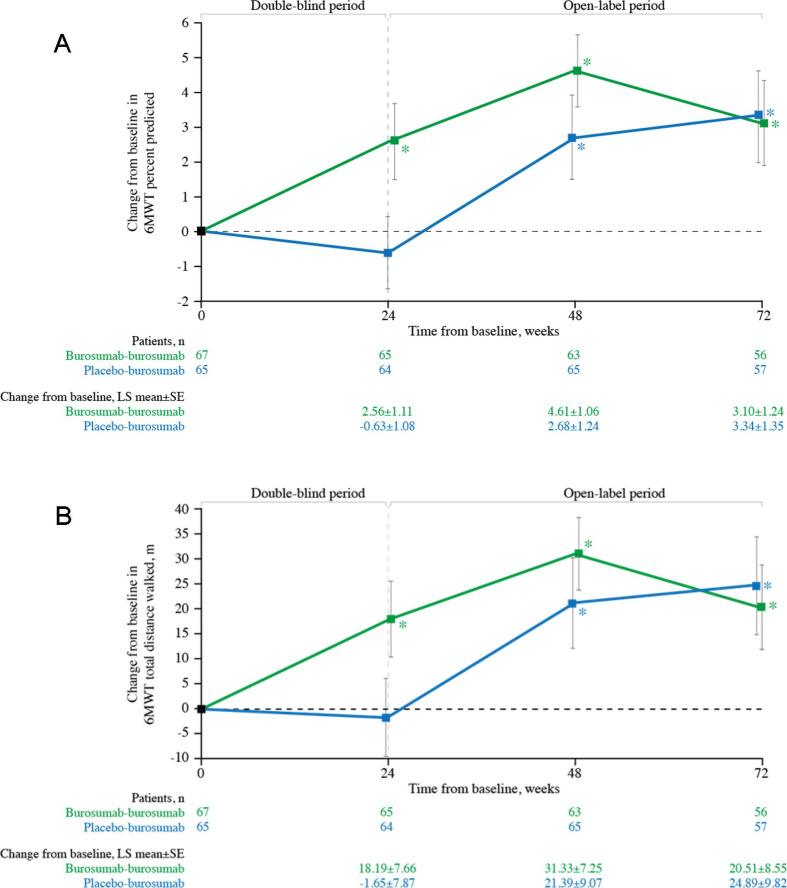

Subjects randomised to burosumab had significant improvements from baseline in 6MWT distance walked (p=0.018; figure 5A) and percent predicted (p=0.021; figure 5B) at week 24. Once all subjects were receiving burosumab at week 48, improvements from baseline in both 6MWT distance walked and percent predicted were observed in the burosumab–burosumab and placebo–burosumab groups (both p<0.05); statistical significance was also observed at week 72 for both treatment groups (both p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Change from baseline in 6MWT (A) distance walked (metres) and (B) percentage predicted (%) (n=132). Data show LS mean (±SE); higher scores indicate better ambulatory function. *p<0.05 for LS mean change from baseline. 6MWT, 6 min walk test; LS, least squares.

Discussion

In adults with XLH, further morbidities develop in addition to those that manifest in childhood, including osteoarthritis, enthesopathies, fractures, pseudofractures and spinal stenosis, which can diminish mobility, physical function and quality of life.5–10 In this extended analysis of a previously reported phase 3 trial of burosumab in adults with XLH, we describe the high level of impairment at baseline and determine the impact of burosumab treatment on a wide range of PRO and ambulatory function endpoints through week 96 and assess clinical meaningfulness to provide a more complete evaluation of the benefit of burosumab for adults with XLH.

Due to the inclusion criteria requiring a BPI-SF worst pain score ≥4, the baseline pain observed in the current study is consistent with or higher than that reported in populations of adults with XLH.5 7 8 In an online survey of 232 adults with XLH,5 the mean BPI-SF worst pain score was 5.1, indicating pain of moderate severity, with a higher worse pain score of 5.6 for adults who reported a history of fracture. Furthermore, 67% of adults reported using pain medication at least once a week and 21% reported prescription pain medication use.5 The mean WOMAC pain score at baseline in the present study was greater than that reported in people with rheumatoid arthritis in a population-based survey (49.3 vs 14.9).24 These data collectively demonstrate that, with current treatment options, pain is a major issue in adults with XLH.

With burosumab treatment, significant improvement from baseline was seen in pain scores as early as week 24; meaningful change was observed at week 48 for pain interference and at week 96 for worst pain (greatest) and pain interference. The mean age of subjects in this study was 40 years and most had XLH-related musculoskeletal morbidities causing chronic pain, including osteomalacia, osteoarthritis, pseudofractures, fractures and enthesopathies.13 14 While pain may be expected to improve with burosumab treatment with the healing of osteomalacia and fractures, some causes of pain may not be amenable to therapies that target FGF23 and thus may not correct the aberrant phosphate homoeostasis in adults with XLH. Osteophytes, osteoarthritis and enthesopathy are structural changes that are unlikely to be affected by treatment with burosumab, thus resulting in residual pain.25 However, these data indicate that adults with pain due to XLH benefit from burosumab treatment, irrespective of their symptoms and baseline radiographic damage, although within the confines of the study inclusion/exclusion criteria requiring the presence of pain and in a population with a mean age of 40 years.

Pain and stiffness associated with XLH can cause significant disability in adults with XLH.5 The baseline mean WOMAC stiffness score indicates that adults in this trial experience substantial stiffness compared with the general population.5 With burosumab, WOMAC stiffness showed significant improvement from baseline as early as week 24. Importantly, meaningful improvement was observed with burosumab at week 48 and at week 96.

The improvements in PROs observed through to 96 weeks highlight the potential benefits of continued burosumab treatment over time. Despite the long-term cumulative complications and physical impairments, maintenance of treatment with burosumab improves symptoms that are clinically meaningful to adults with XLH. This is the first randomised placebo-controlled trial to show therapeutic improvement of patient-relevant musculoskeletal symptoms in adults with XLH over 96 weeks using PRO endpoints that have not been previously reported and with an evaluation of whether observed change from baseline achieved XLH-specific minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs).

This present analysis has several limitations. The subjects of the trial were adults with XLH who were symptomatic despite prior exposure to conventional therapy. After 24 weeks, burosumab treatment was given open label to all subjects; however, subjects and investigators remained blinded to the original treatment assignments until the week 48 analysis was completed to minimise bias. Furthermore, the trial was designed vs placebo to week 24; therefore, analysis of this trial is unable to provide data on the efficacy of conventional therapy on patient-relevant outcomes.

In the trial, there was no radiographical follow-up for the subjects, and as such it is not possible to correlate the PRO changes with some of the potential structural changes.

Subjects were required to maintain a stable dose and schedule of pain medication up to week 24, after which time pain medication could be adjusted as necessary. Although data were collected on change in pain medication use at 24–48 weeks, the analysis and interpretation of the use of pain medication in a clinical trial and over a short time frame is challenging and contrived. The utilisation of pain medication with burosumab treatment should be investigated in the future using real-world evidence from observational studies.26

Finally, although XLH-specific MCIDs have been calculated and published,16 17 20 these are preliminary, and additional work is required to derive MCIDs in larger samples of subjects with XLH and XLH-specific MCIDs for 6MWT distance.

In conclusion, adults with XLH experience substantial burden of disease as a result of musculoskeletal morbidities that have developed despite current treatment options, causing symptoms of pain, stiffness and fatigue, as well as impairment in physical and ambulatory function. Statistically significant improvements from baseline in PROs and ambulatory function were observed early and persisted up to week 96 with burosumab treatment, with predefined meaningful changes observed in pain, stiffness and fatigue. Together, these findings demonstrate that the rapid and sustained improvement in phosphate homoeostasis induced by burosumab treatment is associated with sustained reduction in the substantial burden of disease that has accumulated over the lifetime in adults with musculoskeletal pain related to XLH and suggest that long-term use of burosumab has a role in improving these outcomes in adults with XLH.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants, caregivers and healthcare professionals who participated in this study. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by OPEN Health Medical Communications, with funding provided by Kyowa Kirin International; the authors retain full editorial control over the content and the decision to publish.

Footnotes

Contributors: KB, AAP, MLB, TOC, HIC, MC-S, RKC, RE, YI, SI, KI, NI, SJdB, MKJ, PK, RK, TK, RHL, FP, PP, SHR, YT, HT, TJW, H-WY and EAI were investigators on the study. MN and AN conducted change from baseline statistical analysis of the data with overview by WS. AN and AW drafted the initial manuscript, with support from OPEN Health Medical Communications. All authors provided critical feedback on the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: The trial was funded by Kyowa Kirin International.

Competing interests: The following authors served as clinical investigators for one or more studies, including this trial, sponsored by Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical Inc. in partnership with Kyowa Kirin International: KB, AAP, MLB, TOC, HIC, MC-S, RKC, RE, YI, EAI, SI, NI, SJdB, MKJ, PK, RK, TK, RHL, FP, PP, SHR, YT, HT, TJW, H‑WY and KI. AAP and FP have also received honoraria from Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical for serving as an advisory board member or for lectures. PP has received research funding from Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical and is currently an employee of Ascendis Pharma. SHR has received grants from Kyowa Kirin International and Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical during the conduct of the study. During the conduct of the study, TJW also reports honoraria and travel support from Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical. AW and WS are employees of Kyowa Kirin International plc. AN and MN are employees of Chilli Consultancy and have received consultancy fees from Kyowa Kirin International to support the development of this manuscript and for projects outside this submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Requests for individual deidentified participant data and the clinical study report from this study will be available after product approval to researchers providing a methodologically sound proposal that is in accordance with the Ultragenyx data sharing commitment (www.ultragenyx.com/pipeline/clinical-trial-transparency). To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access and use agreement. Data will be shared via secured portal. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan for this study will be available on the relevant clinical trial registry websites with the tabulated results.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Yale University Institutional Review Board (study approval number: HIC/HSC# 1509016462). The institutional review board or ethics committee of each site approved the study protocol. Investigators obtained written informed consent from each study participant.

References

- 1.HYP Consortium . A gene (PEX) with homologies to endopeptidases is mutated in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. The Hyp Consortium. Nat Genet 1995;11:130–6. 10.1038/ng1095-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsson KB, Zahradnik R, Larsson T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 in oncogenic osteomalacia and X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1656–63. 10.1056/NEJMoa020881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linglart A, Biosse-Duplan M, Briot K, et al. Therapeutic management of hypophosphatemic rickets from infancy to adulthood. Endocr Connect 2014;3:R13–30. 10.1530/EC-13-0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy DC, Murphy WA, Siegel BA, et al. X-linked hypophosphatemia in adults: prevalence of skeletal radiographic and scintigraphic features. Radiology 1989;171:403–14. 10.1148/radiology.171.2.2539609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skrinar A, Dvorak-Ewell M, Evins A, et al. The lifelong impact of X-linked hypophosphatemia: results from a burden of disease survey. J Endocr Soc 2019;3:1321–34. 10.1210/js.2018-00365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theodore-Oklota C, Bonner N, Spencer H, et al. Qualitative research to explore the patient experience of X-linked hypophosphatemia and evaluate the suitability of the BPI-SF and WOMAC® as clinical trial end points. Value Health 2018;21:973–83. 10.1016/j.jval.2018.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Che H, Roux C, Etcheto A, et al. Impaired quality of life in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia and skeletal symptoms. Eur J Endocrinol 2016;174:325–33. 10.1530/EJE-15-0661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forestier-Zhang L, Watts L, Turner A, et al. Health-related quality of life and a cost-utility simulation of adults in the UK with osteogenesis imperfecta, X-linked hypophosphatemia and fibrous dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016;11:160. 10.1186/s13023-016-0538-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo SH, Lachmann R, Williams A, et al. Exploring the burden of X-linked hypophosphatemia: a European multi-country qualitative study. Qual Life Res 2020;29:1883–93. 10.1007/s11136-020-02465-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferizović N, Marshall J, Williams AE, et al. Exploring the burden of X-linked Hypophosphataemia: an opportunistic qualitative study of patient statements generated during a technology appraisal. Adv Ther 2020;37:770–84. 10.1007/s12325-019-01193-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid IR, Hardy DC, Murphy WA, et al. X-linked hypophosphatemia: a clinical, biochemical, and histopathologic assessment of morbidity in adults. Medicine 1989;68:336–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haffner D, Emma F, Eastwood DM, et al. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of X-linked hypophosphataemia. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019;15:435–55. 10.1038/s41581-019-0152-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portale AA, Carpenter TO, Brandi ML, et al. Continued beneficial effects of burosumab in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia: results from a 24-week treatment continuation period after a 24-week double-blind placebo-controlled period. Calcif Tissue Int 2019;105:271–84. 10.1007/s00223-019-00568-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Insogna KL, Briot K, Imel EA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial evaluating the efficacy of Burosumab, an anti-FGF23 antibody, in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia: week 24 primary analysis. J Bone Miner Res 2018;33:1383–93. 10.1002/jbmr.3475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellamy N. WOMAC osteoarthritis index user guide. Version X. Australia: Brisbane, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skrinar A, Theodore-Oklota C, Bonner N. Confirmatory psychometric validation of the Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Inventory (WOMAC) in adult X-linked hypophosphataemia (XLH). Presentation PRO152 at the 2019 ISPOR conference, 2–6 November. Copenhagen, Denmark 2019.

- 17.Skrinar A, Theodore-Oklota C, Bonner N. Confirmatory psychometric validation of the brief pain inventory (BPI-SF) in adult X-linked hypophosphataemia (XLH). Presentation PRO154 at the 2019 ISPOR conference, 2–6 November. Copenhagen, Denmark 2019.

- 18.Cleeland CS. The brief pain inventory. User guide, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer 1999;85:1186–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nixon A, Williams A, Theodore-Oklota C. Psychometric validation of the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) in adult X-linked hypophosphataemia (XLH). Presentation PRO80 at the 2020 ISPOR conference, 18–20 May. Virtual meeting 2020.

- 21.Wyrwich KW, Norquist JM, Lenderking WR, et al. Methods for interpreting change over time in patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2013;22:475–83. 10.1007/s11136-012-0175-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories . ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7. 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbons WJ, Fruchter N, Sloan S, et al. Reference values for a multiple repetition 6-minute walk test in healthy adults older than 20 years. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2001;21:87–93. 10.1097/00008483-200103000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pincus T, Castrejon I, Yazici Y, et al. Osteoarthritis is as severe as rheumatoid arthritis: evidence over 40 years according to the same measure in each disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imel EA. Enthesopathy, osteoarthritis, and mobility in X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:e2649–51. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suvarna VR. Real world evidence (RWE) - Are we (RWE) ready? Perspect Clin Res 2018;9:61–3. 10.4103/picr.PICR_36_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21. 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith SM, Dworkin RH, Turk DC, et al. Interpretation of chronic pain clinical trial outcomes: IMMPACT recommended considerations. Pain 2020;161:2446–61. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Requests for individual deidentified participant data and the clinical study report from this study will be available after product approval to researchers providing a methodologically sound proposal that is in accordance with the Ultragenyx data sharing commitment (www.ultragenyx.com/pipeline/clinical-trial-transparency). To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access and use agreement. Data will be shared via secured portal. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan for this study will be available on the relevant clinical trial registry websites with the tabulated results.