Abstract

Objectives

Knowledge on the impact of heated tobacco product (HTP) use in pregnant women with associated maternal and neonatal risks for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) and low birth weight (LBW) is limited. We aimed to assess the status of HTP use among pregnant women in Japan and explore the association of HTP use with HDP and LBW.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Data from the Japan ‘COVID-19 and Society’ Internet Survey study, a web-based nationwide survey.

Participants

We investigated 558 postdelivery and 365 currently pregnant women in October 2020.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Information on HDP and LBW was collected from the postdelivery women’s Maternal and Child Health Handbooks (maternal and newborn records). We estimated the age-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs of ever HTP smokers for HDP and LBW and compared them with those of never HTP smokers in a logistic regression analysis.

Results

The prevalence of ever and current HTP use were 11.7% and 2.7% in postdelivery women and 12.6% and 1.1% in currently pregnant women, respectively. Among currently pregnant women who were former combustible cigarette smokers, 4.4% (4/91) were current HTP smokers. Among postdelivery women, ever HTP smokers had a higher HDP incidence (13.8% vs 6.5%, p=0.03; age-adjusted OR=2.48, 95% CI 1.11 to 5.53) and higher LBW incidence (18.5% vs 8.9%, p=0.02; age-adjusted OR=2.36, 95% CI 1.16 to 4.87).

Conclusions

In Japan, the incidence of ever HTP use exceeded 10% among pregnant women, and HTP smoking may be associated with maternal and neonatal risks.

Keywords: COVID-19, fetal medicine, maternal medicine, public health, toxicology, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study covered all heated tobacco products (HTPs) available during the study period.

All participants were asked to base their responses on information in their Maternal and Child Health Handbooks, a well-established home-based maternal and neonatal record of pregnancy.

The web-based, self-reported, cross-sectional study had a small sample size and thus involved a selection bias and reduced statistical precision, and causal mechanisms could not be examined.

The lack of information on HTP smoking during pregnancy limited the assessment of the direct impact of HTP use on pregnancy outcomes.

The participants’ relevant medical histories were not assessed.

Introduction

The use of heated tobacco products (HTPs) is an emerging public health concern.1 Since the initial marketing of HTPs in 2014, the prevalence of HTP use has increased in Japan, with a registered prevalence above 15% in the young population aged 20–39 years in 2019.2 This prevalence remained above 15% during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.3 The use of HTPs is increasing worldwide, particularly in the younger population; the prevalence of HTP use among Guatemala adolescents was 2.9% in 2020.4

Although the advertisement of HTPs (eg, reduced harmfulness and a smoke-free image) promotes the impression that HTPs are healthy alternatives to combustible cigarettes,5 HTP-related unfavourable health outcomes, including acute respiratory and cardiovascular risks, are likely to occur.6 7 However, existing knowledge on HTP use and its association with maternal and neonatal risks in pregnant women is limited. The two most common life-threatening maternal and neonatal risks are hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) and low birth weight (LBW).8 9 Although there are controversial reports on the association between HDP and combustible cigarette use,10 combustible cigarettes are known to increase various maternal and neonatal risks in Japan.11 12 Therefore, in this study, we focused on the association of HTP use with HDP and LBW, which are partly linked to other perinatal risks such as preterm birth.

This study aimed to assess the status of HTP use among pregnant women in Japan and explore HTP-associated perinatal risks, in particular the risk of HDP and LBW, by analysing data from a nationwide web-based survey in Japan that contained information on pregnancy, behavioural factors (eg, HTP use and combustible cigarette smoking) and social background.

Materials and methods

Study design, data setting and participants

This cross-sectional internet-based study is part of the Japan COVID-19 and Society Internet Survey (JACSIS) study. The JACSIS study comprises three surveys in the following three target populations: (1) young people and adults aged 15–79 years, (2) currently pregnant and postdelivery women, and (3) adults living in a single-parent household. The study samples for each survey were retrieved from the pooled panels of an internet research agency (Rakuten Insight, which had approximately 2.2 million panellists in 2019).13 We used data from currently pregnant and postdelivery women, which were collected in October 2020.

The internet research agency initially identified 21 896 eligible women who gave birth after October 2019 or who were expected to give birth by March 2021; however, our target sample size was 1000 women due to the available study budget. Using a computer algorithm, the internet research agency randomly selected 4373 women to reach the target sample size of 1000. Quality control methods for the sampling of panellists and other policies for panellists by the internet research agency have been described elsewhere.14 An invitation email was sent to the selected 4373 women; they were to complete the questionnaire through a designated website containing the survey questionnaire (made up of 61 questions, one question per page). Data collection started on 15 October 2020, and ended on 25 October 2020, when the target sample size of 1000 by natural course (response rate, 22.9%) was met. Next, we obtained deidentified data from 1000 women from the internet research agency, and the study population was stratified by delivery date as follows: (1) 600 postdelivery women who delivered in October 2019–October 2020 (the number for October 2019–March 2020, April–May 2020 and June–October 2020 was 200 each) and (2) 400 currently pregnant women who were expected to deliver in October 2020–March 2021.

Seventy-seven (42 postdelivery and 35 currently pregnant women) participants who provided irrelevant or conflicting information were excluded, like it was done in previous studies of the same research agency.15 A total of 923 (558 postdelivery and 365 currently pregnant women) participants were included in the analysis. Informed consent was obtained electronically before the study participants answered the web-based questionnaire.

Definition of HDP and LBW

Data on HDP and LBW were extracted from the web-based self-reported questionnaires. The incidence of HDP was based on whether the study participants had been diagnosed with HDP or pre-eclampsia during pregnancy. The criteria for HDP diagnosis in Japan were derived from the criteria of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ie, systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg after the 20th week of gestation).16 The incidence of LBW was defined on the basis of the diagnosis of LBW (birth weight <2500 g). All municipalities issue a handbook to all pregnant women in which medical professionals record the health information of the mother and child, including clinical outcomes (eg, blood pressure and birth weight) and incident diagnoses (eg, HDP and LBW) during pregnancy; this is part of a national maternal and child health policy. Mothers seldom lose their Maternal and Child Health Handbooks (losing rate, <1%).17

All participants were asked to provide information from their Maternal and Child Health Handbooks. Although the definitions of HDP and LBW were based on diagnosis only (treatment information was not obtained), the information was reliable, since Maternal and Child Health Handbooks are well-established integrated home-based records of maternal, newborn and child health.17 18

HTP and cigarette smoking and other covariates

In the questionnaire, study participants were asked to indicate their smoking status (never, once or a few times (trial smoking and not habitual), former, sometimes (habitual) or every day) for each HTP that was available in the study period (Ploom Tech, Ploom Tech plus, Ploom S, IQOS, glo, glo sens and PULZE). Participants who answered ‘never’ for all HTPs were considered as never HTP smokers; the remaining participants were considered as ever HTP smokers. Therefore, the ever HTP smoking group included those who used HTPs before pregnancy and during pregnancy altogether. We could not specifically distinguish the impacts of HTP smoking during pregnancy from that of HTP smoking before pregnancy.

The status of combustible cigarette smoking was classified as never smoker and ever smoker. It was impossible to further classify the smokers into former or dual smokers due to the nature of the study. The other covariates included age, educational attainment (≤12 years (high school) or ≥13 years (college or university)), occupation (manager or others), household income (<2 million JPY [approximately US$20 000], ¥2 to <¥6 million and ≥¥6 million) and comorbidity (having hypertension or diabetes).19

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed and compared using the t-test or χ2 test. The prevalence of ever HTP smokers was assessed among the postdelivery and currently pregnant women. Additionally, the HTP smoking status was cross-classified according to the combustible cigarette smoking status of the currently pregnant and postdelivery women.

To assess the potential association between HTP smoking and perinatal risk of HDP and LBW, the sample was reduced to 558 postdelivery women who could complete all the assessments during their pregnancy (table 1). In the multivariable logistic regression analyses, the OR and 95% CI of ever HTP smokers for HDP risk were estimated after adjustment for age (model 1, the main model in this study). The never HTP smokers comprised the reference group. In model 2, full adjustments for other explanatory variables (combustible cigarette smoking, educational attainment, occupation, household income and comorbidity) were performed, and 64 participants with missing information on household income were excluded. The same analyses were performed for LBW.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 558 postdelivery women and 365 currently pregnant women

| Characteristics | N (%) or mean (SD) | |||

| Postdelivery women | Currently pregnant women | |||

| Never HTP smokers | Ever HTP smokers | Never HTP smokers | Ever HTP smokers | |

| Overall | n=493 | n=65 | n=319 | n=46 |

| Maternal and neonatal risk | ||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 32 (6.5) | 9 (13.8)* | NA | NA |

| Low birth weight <2500 g | 44 (8.9) | 12 (18.5)* | NA | NA |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks | 19 (3.9) | 4 (6.2) | NA | NA |

| Imminent preterm birth | 82 (16.6) | 18 (27.7)* | NA | NA |

| Age | 32.4 (4.1) | 30.9 (4.2)** | 31.9 (4.3) | 31.3 (4.7) |

| Ever combustible cigarette smoking | 82 (16.6) | 55 (84.6)*** | 54 (16.9) | 41 (89.1)*** |

| Educational attainment ≥13 years | 410 (83.2) | 37 (56.9)*** | 278 (87.1) | 31 (67.4)** |

| Managerial workers | 19 (3.9) | 5 (7.7) | 16 (5.0) | 2 (4.3) |

| Comorbidity of hypertension or diabetes | 35 (7.1) | 4 (6.2) | 4 (1.3) | 4 (8.7)** |

| Household income | n=436 | n=58 | n=263 | n=41 |

| <¥200 million | 13 (3.0) | 3 (5.2) | 6 (2.3) | 1 (2.4) |

| ¥200 to <¥600 million | 200 (45.9) | 30 (51.7) | 115 (43.7) | 19 (46.3) |

| ≥¥600 million | 223 (51.1) | 25 (43.1) | 142 (54.0) | 21 (51.2) |

| Never combustible cigarette smokers | n=411 | n=10 | n=265 | n=5 |

| Maternal and neonatal risk | ||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 26 (6.3) | 1 (10.0) | NA | NA |

| Low birth weight <2500 g | 34 (8.3) | 3 (30.0)* | NA | NA |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks | 17 (4.1) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Imminent preterm birth | 69 (16.8) | 3 (30.0) | NA | NA |

| Age | 32.2 (4.0) | 33.3 (2.3) | 31.7 (4.3) | 30.2 (1.8) |

| Educational attainment ≥13 years | 348 (84.7) | 7 (70) | 235 (88.7) | 4 (80.0) |

| Managerial workers | 16 (3.9) | 1 (10) | 14 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Comorbidity of hypertension or diabetes | 24 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

| Household income | n=361 | n=9 | n=219 | n=5 |

| <¥200 million | 10 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (2.3) | 0 (0) |

| ¥200 to <¥600 million | 160 (44.3) | 4 (44.4) | 97 (44.3) | 3 (60.0) |

| ≥¥600 million | 191 (52.9) | 5 (55.6) | 117 (53.4) | 2 (40.0) |

| Ever combustible cigarette smokers | n=82 | n=55 | n=54 | n=41 |

| Maternal and neonatal risk | ||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 6 (7.3) | 8 (14.5) | NA | NA |

| Low birth weight <2500 g | 10 (12.2) | 9 (16.4) | NA | NA |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks | 2 (2.4) | 4 (7.3) | NA | NA |

| Imminent preterm birth | 13 (15.9) | 15 (27.3) | NA | NA |

| Age | 33.5 (4.3) | 30.5 (4.3)*** | 32.9 (4.2) | 31.4 (5.0) |

| Educational attainment ≥13 years | 62 (75.6) | 30 (54.5)** | 43 (79.6) | 27 (65.9) |

| Managerial workers | 3 (3.7) | 4 (7.3) | 2 (3.7) | 2 (4.9) |

| Comorbidity of hypertension or diabetes | 11 (13.4) | 4 (7.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (9.8)* |

| Household income | n=75 | n=49 | n=44 | n=36 |

| <¥200 million | 3 (4.0) | 3 (6.1) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.8) |

| ¥200 to <¥600 million | 40 (53.3) | 26 (53.1) | 18 (40.9) | 16 (44.4) |

| ≥¥600 million | 32 (42.7) | 20 (40.8) | 25 (56.8) | 19 (52.8) |

*P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 for χ2 test or t-test.

HTP, heated tobacco product; NA, not applicable.

For the sensitivity analysis, a stratified analysis with respect to combustible cigarette smoking (never/ever) was performed. In addition, using a different reference group that included those who never smoked any form of tobacco (HTPs and combustible cigarettes), the ORs of ever HTP smokers for HDP and LBW risks were estimated.

Alpha was set at 0.05, and all p values were two sided. Data were analysed using STATA/MP V.13.1 (StataCorp).

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public was involved.

Results

Among 558 postdelivery women, the incidences of HDP and LBW were 7.3% (n=41) and 10.0% (n=56), respectively, and the prevalence of ever HTP smokers was 11.7% (n=65, table 1). Furthermore, among the 365 currently pregnant women, the prevalence of ever HTP smokers was 12.6% (n=46), which did not differ from that of HTP smokers among postdelivery women (p=0.66).

Among the currently pregnant women, 4.4% (4/91 participants) of the former combustible cigarette smokers reported smoking HTPs during pregnancy (table 2), corresponding to 1.1% (4/365 participants) of currently pregnant women. In addition, 36.3% (33/91 participants) of former combustible cigarette smokers quitted HTP smoking during pregnancy, corresponding to 11.5% (42/365 participants) of currently pregnant women.

Table 2.

Smoking status and use of heated tobacco products cross-classified according to combustible cigarette smoking status

| Characteristics | HTP smoking status | |||

| Never (%) | Former (%) | Current (%) | Total (%) | |

| Postdelivery women, total | 493 (88.4) | 50 (9.0) | 15 (2.7) | 558 (100) |

| Never combustible cigarette smokers | 411 (97.6) | 9 (2.1) | 1 (0.2) | 421 (100) |

| Former combustible cigarette smokers | 79 (64.2) | 32 (26.0) | 12 (9.8) | 123 (100) |

| Current combustible cigarette smokers | 3 (21.4) | 9 (64.3) | 2 (14.3) | 14 (100) |

| Currently pregnant women, total | 319 (87.4) | 42 (11.5) | 4 (1.1) | 365 (100) |

| Never combustible cigarette smokers | 265 (98.1) | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 270 (100) |

| Former combustible cigarette smokers | 54 (59.3) | 33 (36.3) | 4 (4.4) | 91 (100) |

| Current combustible cigarette smokers | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) |

HTP, heated tobacco product;

Among the postdelivery women, the HDP incidence was higher in ever HTP smokers than in never HTP smokers (13.8% (n=9) vs 6.5% (n=35), p=0.03; table 1). Similarly, the incidence of LBW was higher among ever HTP smokers than among never HTP smokers (18.5% (n=12) vs 8.9% (n=44), p=0.02; table 1). When stratified by combustible cigarette smoking, a similar pattern was observed among never and ever combustible cigarette smokers (table 1).

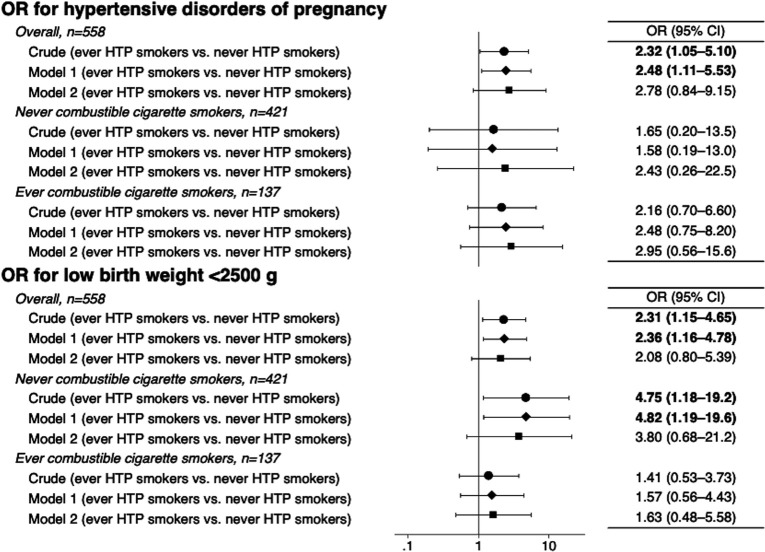

In the regression analysis, the age-adjusted ORs for HDP and LBW were elevated in ever HTP smokers (model 1); the ORs for HDP and LBW were 2.48 (95% CI 1.11 to 5.53) and 2.36 (95% CI 1.16 to 4.78), respectively. However, the elevated ORs were not significant after adjusting for other covariates (model 2, figure 1). In the same regression analyses (model 2), while ever combustible cigarette smokers were not associated with perinatal outcomes, the ORs of managerial workers for HDP and LBW were 3.92 (95% CI 1.16 to 13.2) and 3.74 (95% CI 1.41 to 9.93), respectively.

Figure 1.

OR of ever heated tobacco product (HTP) smokers with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and low birth weight, compared with never HTP smokers. Age was adjusted in model 1, and other covariates (combustible cigarette smoking, educational attainment, occupation, household income and comorbidity) were additionally adjusted in model 2. The samples for each analysis in model 2 were as follows: n=494 (overall), n=370 (never combustible cigarette smokers), and n=124 (ever combustible cigarette smokers) for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; and n=478 (overall), n=310 (never combustible cigarette smokers) and n=118 (ever combustible cigarette smokers) for low birth weight.

In the sensitivity analyses, when stratified by combustible cigarette smoking, a similar pattern was observed independently in never and ever combustible cigarette smokers (figure 1). For instance, among never combustible cigarette smokers, the age-adjusted OR of HTP use for LBW was 4.82 (95% CI 1.19 to 19.6). A further analysis comparing 65 ever HTP smokers in the postdelivery group and 411 never tobacco smokers showed similar results: compared with those who never smoked any form of tobacco, the age-adjusted ORs of ever HTP smokers for HDP and LBW were 2.56 (95% CI 1.13 to 5.80) and 2.52 (95% CI 1.22 to 5.20), respectively (model 1). However, after adjusting for other covariates (model 2), the ORs were not significant due to the small sample size: the ORs for HDP and LBW were 2.40 (95% CI 0.27 to 21.2) and 3.59 (95% CI 0.66 to 19.5), respectively.

Discussion

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, the incidence of HTP use among pregnant women exceeded 10%, and there was a suspected association of HTP use and perinatal risk of HDP and LBW. However, after adjusting for potential explanatory factors, there was no significant association, which may be due to the weak statistical power because of the small sample size.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a potential association between HTP use and perinatal risks. Although smoking plays a controversial role,10 recent evidence suggests that combustible cigarette smoking is associated with increased HDP risk.11 12 Although the biological and genetic pathways (eg, CYP2A6 and nicotine) underlying the associations observed in different phenotypes of HDP (eg, pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension) have not been elucidated,20 HDP is recognised as a systemic disease attributable to placental circulatory dysfunction.21 In experimental research, aerosol from HTPs was found to damage vascular endothelial function in rats.6 Therefore, the association between HDP risk and HTP use may involve acute and chronic vascular damage, irrespective of combustible cigarette smoking. Furthermore, as concluded in a recent systematic review, smoking is a strong risk factor for LBW.22 Thus, given the fact that HTPs are smoking devices, our observed results are in line with established reports.

Although HTP-related unfavourable health outcomes (eg, acute respiratory and cardiovascular risks) are likely to occur,6 7 the impression of HTPs as a healthy alternative is promoted by HTP use advertisements.5 The Japanese HTP market share accounted for 21% of total tobacco sales in 2018, and the weak restrictions on tobacco advertisements and promotion in this country contribute to increased HTP use.23 Among currently pregnant women, approximately 4% of former combustible cigarette smokers reported smoking HTPs in the present study. This result might explain the change from combustible cigarettes to HTP smoking during pregnancy. In a setting of weak tobacco restrictions such as Guatemala, even though the prevalence of HTP use is low (2.9%) among adolescents, a high prevalence is anticipated.4 However, our findings imply that HTP use is not a healthy alternative. Evidence for unfavourable HTP-related health outcomes is still insufficient, particularly among reproductive age women. In addition, the impact of multidimensional factors of the COVID-19 pandemic (eg, the infection, mental health and socioeconomic factors) and the smoking behaviours of others (eg, partners and family) on the association between HTP use and perinatal risks remains unknown. The ongoing JACSIS study may provide updates in this regard.

Our study has limitations. First, this web-based, self-reported, cross-sectional study had a small sample size, which may thus involve a selection bias and weak statistical precision, and it cannot provide an explanation of the causal mechanisms between HTP use and perinatal risks. Due to the lack of information on HTP smoking during the pregnancy, the direct impact of HTP smoking on pregnancy outcomes could not be assessed. Furthermore, details on the participants’ medical histories including relevant comorbidities, and detailed smoking information such as smoking intensity and duration of smoking abstinence were not available. In addition, electronic cigarette use was not assessed. However, the prevalences of HDP and HTP smokers were mostly parallel to the general population in Japan.2 3 16 The incidence of HTP use did not differ between postdelivery and currently pregnant women in our study. Second, recall and reporting bias of HTP use could not be discarded, as suggested in a study on combustible cigarette and electronic cigarette smoking.4 Because self-report-based smoking status among pregnant women tends to misclassify ever smokers as never smokers,24 our estimates might be biased toward the null. Third, the perinatal clinical information was self-reported and not based on medical charts, thereby limiting the precision of the results. However, all participants were asked to base their responses on information in their Maternal and Child Health Handbooks, a well-established home-based maternal and neonatal record during pregnancy.18 Therefore, this limitation might not have affected our results, or at least not largely. Despite these limitations, all HTPs that were available during the study period were assessed. This is the first report on the status of HTP use among pregnant women in Japan, and it highlights the potentially elevated maternal and neonatal risks associated with HTP use. Additionally, to date, besides the present study, no other human studies have assessed the potential effect of the maternal use of new tobacco products (ie, e-cigarettes and HTPs) on perinatal health.25 Therefore, our findings shed light and motivate further investigations to assess the life-threatening perinatal risks associated with new tobacco products.

In conclusion, the incidence of HTP use seems to exceed 10% among pregnant women, and HTP smoking may be associated with increased maternal and neonatal risks in Japan. Undoubtedly, smoking in reproductive age women can cause unfavourable perinatal outcomes.26 Hence, efforts should be made to investigate the risk of HTP use in reproductive age women, to prevent life-threatening perinatal complications and deaths.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Twitter: @TakahiroTabuchi

MZ and YH contributed equally.

Contributors: MZ and TT designed the study. TT supervised the study. MZ, YH and SO developed the methodology. SO, AH and TT created the dataset. MZ and YH analysed the data. MZ and YH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SO, AH, GK and TT commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was partly supported by Health, Labour and Welfare Sciences Research Grants (20FA1005) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI JP18K17351).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request. However, restrictions apply to the availability of these data due to personal identification; research data are not shared. If any person wishes to verify our data, they are most welcome to contact the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Osaka International Cancer Institute approved the study (Protocol Number 20084).

References

- 1.Tabuchi T, Gallus S, Shinozaki T, et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco product use in Japan: its prevalence, predictors and perceived symptoms from exposure to secondhand heat-not-burn tobacco aerosol. Tob Control 2018;27:e25–33. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hori A, Tabuchi T, Kunugita N. Rapid increase in heated tobacco product (HTP) use from 2015 to 2019: from the Japan 'Society and New Tobacco' Internet Survey (JASTIS). Tob Control 2020 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055652. [Epub ahead of print: 05 Jun 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odani S, Tabuchi T. Prevalence of heated tobacco product use in Japan: the 2020 JASTIS study. Tob Control 2021. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056257. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Mar 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottschlich A, Mus S, Monzon JC, et al. Cross-sectional study on the awareness, susceptibility and use of heated tobacco products among adolescents in Guatemala City, Guatemala. BMJ Open 2020;10:e039792. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hair EC, Bennett M, Sheen E, et al. Examining perceptions about IQOS heated tobacco product: consumer studies in Japan and Switzerland. Tob Control 2018;27:s70–3. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nabavizadeh P, Liu J, Havel CM, et al. Vascular endothelial function is impaired by aerosol from a single IQOS HeatStick to the same extent as by cigarette smoke. Tob Control 2018;27:s13–19. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonavicius E, McNeill A, Shahab L, et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: a systematic literature review. Tob Control 2019;28:582–94. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duley L. The global impact of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Semin Perinatol 2009;33:130–7. 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa J, Sekizawa A, Tanaka H, et al. Current status of pregnancy-related maternal mortality in Japan: a report from the maternal death exploratory Committee in Japan. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010304. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.England L, Zhang J. Smoking and risk of preeclampsia: a systematic review. Front Biosci 2007;12:2471–83. 10.2741/2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi K, Matsuda Y, Kawamichi Y, et al. Smoking during pregnancy increases risks of various obstetric complications: a case-cohort study of the Japan perinatal registry network database. J Epidemiol 2011;21:61–6. 10.2188/jea.JE20100092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka K, Nishigori H, Watanabe Z, et al. Higher prevalence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in women who smoke: the Japan environment and children's study. Hypertens Res 2019;42:558–66. 10.1038/s41440-019-0206-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rakuten Insight Inc . Rakuten. Available: https://insight.rakuten.co.jp/en/aboutus.html [Accessed 26 Jun 2021].

- 14.Rakuten Insight Inc . Policies, 2019. Available: https://member.insight.rakuten.co.in/policies [Accessed 26 Jun 2021].

- 15.Tabuchi T, Shinozaki T, Kunugita N, et al. Study Profile: The Japan "Society and New Tobacco" Internet Survey (JASTIS): A Longitudinal Internet Cohort Study of Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Products, Electronic Cigarettes, and Conventional Tobacco Products in Japan. J Epidemiol 2019;29:444–50. 10.2188/jea.JE20180116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umesawa M, Kobashi G. Epidemiology of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: prevalence, risk factors, predictors and prognosis. Hypertens Res 2017;40:213–20. 10.1038/hr.2016.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimoto S, Nakamura Y, Ikeda M, et al. [Utilization of maternal and child health handbook in Japan]. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2001;48:486–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osaki K, Hattori T, Toda A, et al. Maternal and child health Handbook use for maternal and child care: a cluster randomized controlled study in rural Java, Indonesia. J Public Health 2019;41:170–82. 10.1093/pubmed/fdx175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Igarashi A, Aida J, Kusama T, et al. Heated tobacco products have reached younger or more affluent people in Japan. J Epidemiol 2021;31:187–93. 10.2188/jea.JE20190260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakajima M, Yamagishi S, Yamamoto H, et al. Deficient cotinine formation from nicotine is attributed to the whole deletion of the CYP2A6 gene in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000;67:57–69. 10.1067/mcp.2000.103957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshihara T, Zaitsu M, Kubota S, et al. Pool walking may improve renal function by suppressing the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in healthy pregnant women. Sci Rep 2020;10:2891. 10.1038/s41598-020-59598-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abraham M, Alramadhan S, Iniguez C, et al. A systematic review of maternal smoking during pregnancy and fetal measurements with meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170946. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craig LV, Yoshimi I, Fong GT, et al. Awareness of marketing of heated tobacco products and cigarettes and support for tobacco marketing restrictions in Japan: findings from the 2018 international tobacco control (ITC) Japan survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:8418. 10.3390/ijerph17228418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishihama Y, Nakayama SF, Tabuchi T, et al. Determination of urinary cotinine cut-off concentrations for pregnant women in the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:5537. 10.3390/ijerph17155537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larcombe AN. Early-life exposure to electronic cigarettes: cause for concern. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:985–92. 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30189-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atrash HK, Johnson K, Adams M, et al. Preconception care for improving perinatal outcomes: the time to act. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:3–11. 10.1007/s10995-006-0100-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request. However, restrictions apply to the availability of these data due to personal identification; research data are not shared. If any person wishes to verify our data, they are most welcome to contact the corresponding author.