Abstract

The RAD54 gene has an essential role in the repair of double-strand breaks (DSBs) via homologous recombination in yeast as well as in higher eukaryotes. A Drosophila melanogaster strain deficient in the RAD54 homolog DmRAD54 is characterized by increased X-ray and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) sensitivity. In addition, DmRAD54 is involved in the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links, as is shown here. However, whereas X-ray-induced loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) events were completely absent in DmRAD54−/− flies, treatment with cross-linking agents or MMS resulted in only a slight reduction in LOH events in comparison with those in wild-type flies. To investigate the relative contributions of recombinational repair and nonhomologous end joining in DSB repair, a DmRad54−/−/DmKu70−/− double mutant was generated. Compared with both single mutants, a strong synergistic increase in X-ray sensitivity was observed in the double mutant. No similar increase in sensitivity was seen after treatment with MMS. Apparently, the two DSB repair pathways overlap much less in the repair of MMS-induced lesions than in that of X-ray-induced lesions. Excision of P transposable elements in Drosophila involves the formation of site-specific DSBs. In the absence of the DmRAD54 gene product, no male flies could be recovered after the excision of a single P element and the survival of females was reduced to 10% compared to that of wild-type flies. P-element excision involves the formation of two DSBs which have identical 3′ overhangs of 17 nucleotides. The crucial role of homologous recombination in the repair of these DSBs may be related to the very specific nature of the breaks.

Double-strand breaks (DSBs) are important DNA lesions that, if left unrepaired, can lead to broken chromosomes and cell death and, if repaired improperly, can result in chromosomal rearrangements. In cells of higher organisms, the formation and repair of DSBs are intrinsic to a number of biological processes such as meiotic recombination, V(D)J recombination in differentiating lymphocytes, and transposition of certain mobile DNA elements. Furthermore, DSBs can be induced upon exposure to exogeneous factors such as ionizing radiation and may arise indirectly after treatment with chemical agents such as methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) and cross-linking agents. In eukaryotes, repair of DSBs can occur by at least two pathways: (i) nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and (ii) repair via homologous recombination (recombinational repair).

Repair of DSBs by NHEJ was first studied in higher eukaryotes by using rodent cell mutants (11, 44). Genes known to be involved in this pathway are DNA-PKcs, Ku80, Ku70, XRCC4, and Ligase IV. Cell lines with defects in NHEJ are impaired in V(D)J rearrangement and are sensitive to ionizing radiation. Homologs of Ku70, Ku80, XRCC4, and Ligase IV have been identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (6, 16, 23, 35, 43, 45). Yeast mutants defective in one of these genes are hardly sensitive to ionizing radiation. A contribution of NHEJ can be detected only in the absence of recombinational repair, indicating that recombinational repair is the predominant mechanism for DSB repair in yeast (7, 28, 38). The homolog of Ku70 in Drosophila melanogaster, DmKu70, is encoded by the mus309 gene (1, 2, 24). Flies with mutations of this gene are hypersensitive to MMS (9).

Repair of DSBs through homologous recombination has been extensively studied in the yeast S. cerevisiae and is dependent on the RAD52 group genes (RAD50, RAD51, RAD52, RAD54, RAD55, RAD57, RAD59, MRE11 [RAD58/XRS4], XRS2, and RDH54/TID1) (references 25 and 37; reviewed in references 18 and 30). Yeast strains deficient in one of these genes have an increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation; rad51, rad52, and rad54 mutants have the most severe phenotype. Furthermore, these three mutants have defects in spontaneous and induced mitotic recombination and mating type switching, rad51 and rad52 mutants are also impaired in meiotic recombination, and the formation of viable spores is almost completely blocked. Rad51 is the eukaryotic homolog of RecA and has limited pairing and strand exchange activities (39). The strand exchange activities of Rad51 are stimulated by Rad52 or by a heterodimer of Rad55 and Rad57 by overcoming the inhibitory effects of replication protein A (29, 36, 40, 41). The Rad54 protein, which has a double-stranded DNA-dependent ATPase activity, also stimulates the Rad51-dependent formation of heteroduplex DNA (33).

During the past few years, homologs of the RAD52 group genes have been identified in higher eukaryotes. Both structurally and functionally these homologs resemble their counterparts from yeast (18, 32). Recently, we have identified the RAD54 homolog in D. melanogaster, DmRAD54 (26). Flies with mutations in this gene are characterized by an increased sensitivity of the larvae to X rays and MMS. Furthermore, the DmRAD54 mutant is defective in X-ray-induced recombination in somatic cells. Similar results have been reported for RAD54-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells and chicken DT40 cells (5, 15). In contrast to RAD54−/− mice, DmRAD54-deficient flies have meiotic defects. Mutant males are fertile, but females are sterile due to inviability of the eggs. Defects in meiotic recombination, which occurs only in females in Drosophila, possibly affects patterning during oogenesis, as was recently shown by Ghabrial et al. (19). Together, the analysis of RAD54-deficient fly strains and mouse and chicken cells demonstrates that, besides NHEJ, recombinational repair contributes to the repair of DSBs in higher eukaryotes.

In the present study we have examined the role of DmRAD54 in DSB repair in more detail. One important source of site-specific DSBs in Drosophila is the excision of P transposable elements. Full-length P elements are 2.9 kb in length and contain 31-bp terminal inverted repeats (31). The P-element-encoded transposase binds to inverted repeats and introduces two site-specific DSBs with identical 17-nucleotide 3′ extensions (3). Genetic studies have shown that repair of the breaks can occur by gene conversion using the sister chromatid, the homologous chromosome, or an ectopically located homologous sequence as a template, indicating an important role for the recombinational-repair mechanism (14). To study the role of DmRAD54 in this process, we introduced a DmRAD54 mutation in flies containing all the elements required for P-element excision. The results obtained indicate an important role for DmRad54 in the repair of DSBs after P-element excision.

The involvement of recombinational repair in overcoming cross-links in the DNA was examined by determining the larval sensitivity of DmRAD54 mutant flies to the cross-linking agents mitomycin C (MMC) and cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (cisDDP). Simultaneously, we examined the levels of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in somatic cells after treatment with these agents or MMS. To investigate the relative contributions of NHEJ and recombinational repair in Drosophila, a DmRAD54 mutation was combined with a mutation in the DmKu70 gene. Survival experiments suggest a strong synergism between recombinational repair and NHEJ in the repair of X-ray damage but not in the repair of MMS-induced DNA damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains and chromosomes.

The DmRAD54-deficient fly strain DmRAD54A17-11 cn bw/Df(2L)JS17 has been described previously (26). Briefly, the A17-11 mutation is a GC-to-AT transition at the splice acceptor site of the second intron in the DmRAD54 gene. The DmRAD54A17-11 allele is referred to below as A17-11, and deficiency chromosome Df(2L)JS17 is referred to as JS17. From the experiment that resulted in the isolation of the A17-11 mutant, a second DmRAD54 mutant, called DmRAD54A19-10 cn bw (referred to below as A19-10), was isolated. This mutant contains an AT-to-GC transition mutation resulting in a V146D amino acid alteration. The valine at this position is also present in Rad54 proteins from yeast and mammals. Hemizygous mutants A19-10/JS17 and heteroallelic homozygous A19-10/A17-11 mutants have the same MMS and X-ray hypersensitivity as the A17-11/JS17 mutant strain, and the females in both mutant strains are sterile.

For the construction of a DmRAD54/mus309(DmKu70) double mutant, balancer chromosomes with visible dominant marker mutations were used; Cy and Pm indicate the second chromosome balancers SM5 and In(2LR)bwV1, respectively, and Ubx and Sb indicate the third chromosome balancers TM2 and TM3, respectively (27). These chromosomes suppress meiotic recombination and can be monitored directly in the F1 generation due to the presence of the visible dominant markers. The DmRAD54−/− mutant was made by combining the allele A17-11 with the allele A19-10. JS17 was not used for the construction of the double mutant, since strains with this deletion combined with a mus309 allele and two balancer chromosomes showed very poor viability. Two alleles, mus309D2 and mus309D3, had to be combined to obtain a homozygous mus309 mutant, since both chromosomes contain additional recessive lethal mutations. The final cross that was made to determine the sensitivities of the single mutants and the double mutant to ionizing radiation was A17-11 cn bw/Cy; mus309D2/Ubx × A19-10 cn bw/Pm; mus309D3/Sb and resulted in 16 different phenotypes in the F1 offspring. According to Mendelian laws, nine types of flies are homozygous or heterozygous wild type for both genes, three types are homozygous mus309 mutants, three types are homozygous DmRAD54 mutants, and only one type is a double mutant.

The somatic mutation and recombination test (SMART) was performed as described previously (26). For each point in the assay, at least 200 eyes were scored.

Drosophila strains y wa spl and y whd spl; P[walter]25F/CyO were kindly provided by Carlos Flores and William R. Engels. The wa allele results from a copia- element insertion in the second intron of the white gene. The mus309 alleles D2 and D3 as well as the Df(2L)JS17 strain, were kindly provided by Jeff Sekelsky. Other strains were obtained from the Drosophila Stock Center in Bloomington, Ind., and are described by Lindsley and Zimm (27) and in FlyBase (17).

P-element excision assay.

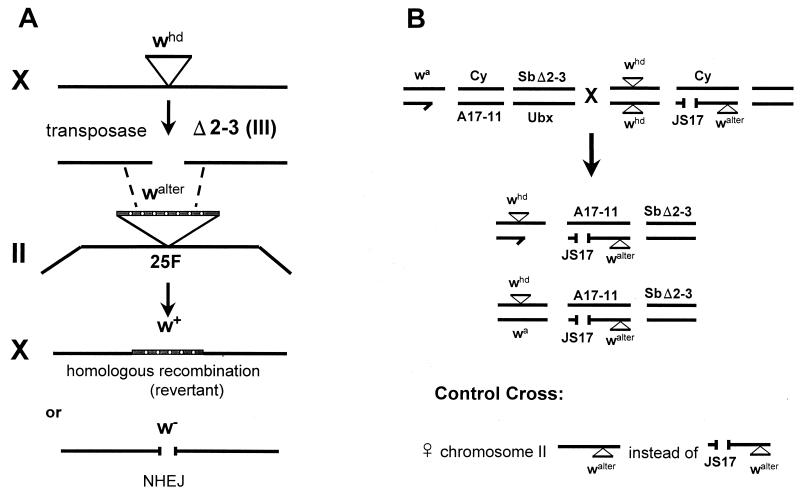

To study DSB repair after P-element excision, the whd (whd80617) element was used. This mutant allele of the X-chromosome-linked white gene carries a small P element of 629 bp in exon 6 (20). P[walter] was incorporated in the system as a template for recombination. The P[walter] element contains an altered white minigene in a P-element vector located in region 25F of the second chromosome (20). Although the white minigene carries 12 base pair substitutions, it encodes a wild-type white gene product. Due to position effects at the site of integration at 25F, the walter gene is hardly expressed. By standard genetic crosses a recombinant second chromosome was obtained, carrying the JS17 deletion, which uncovers the DmRAD54 gene together with walter. The transposase required for excision of the whd element is encoded by the P[ry+Δ2-3] element (abbreviated as Δ2-3) at position 99B on the third chromosome (24). To combine all the elements required for P-element excision and repair, y wa spl; A17-11 cn bw/Cy; Sb P[ry+Δ2-3]/Ubx males were crossed to whd/whd; JS17 walter/Cy females. In the DmRAD54-proficient control cross, whd/whd; walter/Cy females were used (see Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

(A) Mechanism of induction and repair of a single DSB after P-element excision. The whd element has an internal deletion and does not code for a functional P-element transposase. It is excised by the transposase encoded by the Δ2-3 element on the third chromosome, leaving behind a DSB. In males this DSB can be repaired via homologous recombination using the walter template, located at position 25F on the second chromosome, resulting in a functional white gene. Repair via NHEJ will in most cases result in a nonfunctional white gene. Females can also use the wa allele on the other X chromosome as a template. (B) Cross to combine the whd transposition system with a DmRAD54-deficient background. Cy and Ubx are dominant marker mutations on the second and third balancer chromosomes, respectively. The third chromosome, carrying the Δ2-3 element, is marked by the dominant Sb mutation. The males used in this cross carry the wa mutation on the X chromosome to ensure a white-eye background in the female offspring. In the control cross, DmRAD54-proficient females carrying a second chromosome containing only the walter construct were used.

Treatment of Drosophila with DNA-damaging agents.

Sensitivity to different DNA-damaging agents is dependent on the developmental stage of Drosophila, and therefore larvae of different stages were used for the various treatments. To obtain optimal results, 0- to 24-h embryos were X-ray irradiated, 24- to 48-h larvae were treated with 0.2 ml of MMS in water, and 48- to 72-h larvae were treated with 0.2 ml of MMC in water or 0.2 ml of cis-DDP in 0.4% dimethylformamide. Untreated larvae of the same parents were used as controls. Unless noted otherwise, A17-11/Cy females were crossed to JS17/Cy males. Fly cultures were grown at 25°C, and the offspring was analyzed after 12 to 18 days. To calculate the relative sensitivity, the ratio between homozygous mutants A17-11/JS17 and heterozygous A17-11/Cy and JS17/Cy flies was determined. This ratio is theoretically 0.5 in untreated samples, according to Mendelian laws. If the sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents is increased, this ratio of 0.5 will decrease as the dose increases. The relative sensitivity can be calculated by dividing the ratio of the untreated sample by the ratio of the treated sample. In the case of the DmRAD54/mus309 double mutant, the ratio between homozygous or heterozygous wild-type flies, mus309 mutants, DmRAD54 mutants, and double-mutant flies is 9:3:3:1 according to Mendelian laws. After treatment the number of flies of each class is corrected for these ratios before the relative sensitivities are calculated.

RESULTS

DmRAD54 is crucial for DSB repair after P-element transposition.

One of the first steps in P-element transposition in Drosophila is the formation of two staggered DSBs at the P-element termini. Reversion of the donor site to wild type is dependent on the presence of sequence information on the homologous chromosome or an ectopic template. To investigate the role of DmRAD54 in this process, DSB repair after P-element excision was studied in a DmRAD54−/− background. The whd allele of white, which carries a small P-element insertion in exon 6, was used as a detection system for correct repair. Flies homozygous for the whd mutation have bleached white eyes. The walter sequence on the second chromosome can be used as a template for recombinational repair. The transposase required for excision of the whd element is supplied by crossing whd females to male flies carrying the Δ2-3 element on the third chromosome, which provides the transposase protein for induction of site-specific DSBs (34). A second chromosome, carrying only the walter element and not the JS17 deletion, was used as a DmRAD54-proficient control. Figure 1B shows the cross that was used and the two types of flies (male and female) that emerge from this cross carrying all the necessary components. According to Mendelian laws, in the offspring of the DmRAD54-deficient as well as the DmRAD54-proficient cross, half of the flies that are recovered carry the transposase source (marked by the dominant Sb mutation). Excision of whd by the transposase during development may give rise to cells expressing a wild-type white gene as a result of recombinational repair using walter as a template. Clonal expansion results in spots of wild-type colored tissues against a colorless background in the eyes of the adult flies. Male flies from the initial cross (Fig. 1B) carried the mutant whiteapricot (wa) allele. As a result the female offspring also have white eyes. In females the wa allele can also be used as a template for homologous recombination in addition to walter. Table 1 shows the numbers of the most indicative flies that emerged from the cross and the numbers of eyes from these flies that contained one or more spots. In the DmRAD54-proficient control, the different groups of flies hatched in equal ratios. Flies without the transposase (indicated by the Ubx marker) did not have red spots, as expected, and a majority of the eyes in flies with the transposase contained one or more red spots. However, from the DmRAD54-deficient cross, only flies without the transposase emerged in a normal ratio. Male DmRAD54−/− larvae in which P-element excision was induced did not survive at all, and the proportion of female DmRAD54−/− flies was reduced to 10% relative to the females that did not have the transposase. Furthermore, the frequency of red spots in the DmRAD54−/− female flies that did emerge was reduced fivefold compared to that in the corresponding DmRAD54+/− female group. These results clearly show a crucial role for DmRAD54 in the repair of P-element transposase-induced DSBs.

TABLE 1.

Survival and reversion frequency after P-element excision

| Sex | Phenotype |

DmRAD54+/−

|

DmRAD54−/−

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of flies | No. of eyes with spots | No. of flies | No. of eyes with spots | ||

| Male | No transposasea | 76 | 0 | 99 | 0 |

| Transposaseb | 69 | 97 | 0 | ||

| Female | No transposasea | 71 | 0 | 96 | 0 |

| Transposaseb | 77 | 132 | 9 | 3 | |

Third chromosome marked with Ubx.

Third chromosome marked with Sb and containing the Δ2-3 transposase source.

DmRAD54 is involved in the repair of DNA cross-links.

Recently, we showed that DmRAD54 is involved in the repair of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation and MMS. To determine if homologous recombination is involved in cross-link repair, the sensitivity of the DmRAD54−/− mutant to MMC and cisDDP was tested. Heterozygous DmRAD54+/− flies were crossed, and the offspring were treated as 48- to 72-h-old larvae with increasing doses of MMC or cisDDP. The relative sensitivities were calculated using the ratios of emerging DmRAD54−/− flies and DmRAD54+/− flies with or without treatment as described in Materials and Methods. Table 2 shows a dose-dependent increase in sensitivity to both agents for the DmRAD54−/− flies. At a dose of 0.3 mM MMC, the sensitivity was increased by a factor of 6.8. In the case of treatment with 1 mM cisDDP, the DmRAD54−/− larvae were 6.4 times more sensitive than the DmRAD54+/− control larvae. After exposure to higher doses, or at an earlier stage of development, the sensitivities increased further, but these doses were too toxic for the control group and sensitivities could not be calculated accurately any more.

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity to cross-linking agents

| Agent | Concn (mM) | No. of flies

|

Ratioa | Sensitivityb of DmRAD54−/− flies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DmRAD54−/− | DmRAD54+/− | ||||

| MMC | 0 | 481 | 1,012 | 0.48 | |

| 0.05 | 371 | 1,074 | 0.34 | 1.4 | |

| 0.2 | 98 | 374 | 0.26 | 1.8 | |

| 0.3 | 88 | 530 | 0.07 | 6.8 | |

| cisDDP | 0 | 378 | 866 | 0.44 | |

| 0.04 | 88 | 198 | 0.44 | 1.0 | |

| 0.2 | 54 | 158 | 0.34 | 1.3 | |

| 1.0 | 12 | 173 | 0.07 | 6.4 | |

Number of DmRAD54−/− flies divided by the number of DmRAD54+/− flies.

Obtained by dividing the ratio of the treated sample by the ratio of the untreated sample.

Somatic recombination induced by cross-linking agents or MMS occurs at a reduced level in DmRAD54-deficient flies.

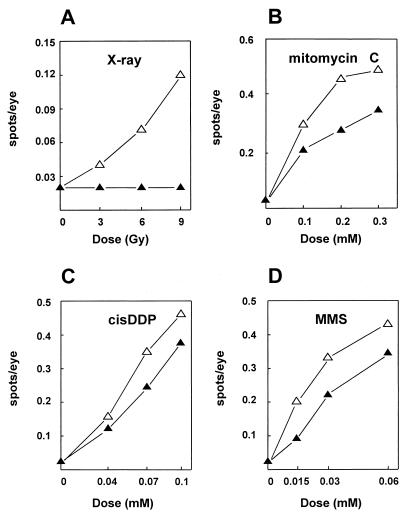

It has previously been shown that somatic recombination induced by X rays was completely absent in DmRAD54−/− flies (26). This system measures the LOH of both wild-type genes for cinnabar (cn) and brown (bw) in a heterozygous (cn bw/++) larval eye precursor cell due to a mutagenic event. Clonal expansion results in a colorless spot against a wild-type red background in the eyes of adult flies. The sensitivity to the alkylating agent MMS and to the cross-linking agents MMC and cisDDP raised the question whether the induction of LOH events by these agents is also affected. Figure 2 shows that treatment with each mutagen resulted in a dose-dependent increase in the number of spots per eye in DmRAD54-proficient flies. In the DmRAD54−/− flies, no induction of spots was seen after exposure to ionizing radiation (Fig. 2A). However, after exposure to MMS, MMC, or cisDDP, induction of spots is still possible in DmRAD54 mutant flies, although at a reduced level compared to that in the control group (Fig. 2B through D). Apparently, the majority of LOH events induced by these chemical agents occur in a DmRAD54-independent way.

FIG. 2.

Somatic recombination induced by DNA-damaging agents in a DmRAD54-deficient background. DmRAD54-proficient control larvae (▵) and DmRAD54-deficient larvae (▴) were treated with increasing doses of ionizing radiation (A), the cross-linking agent MMC (B) or cisDDP (C), or the alkylating agent MMS (D). Twelve to 18 days after treatment, the eyes of the adult flies were scored for colorless spots. Each spot is caused by one LOH event. Results are presented as spots per eye; for each point, at least 200 eyes were scored.

DmRAD54 and DmKu70 act synergistically in the repair of X-ray damage but not in the repair of damage induced by MMS.

To examine the relative contributions of recombinational repair and NHEJ in Drosophila, a double mutant was generated. For this purpose DmRAD54+/−/DmKu70+/− heterozygous females and males were crossed, and the larvae obtained were treated with X rays or MMS. From this cross double-mutant flies, both single mutants, and homozygous or heterozygous wild-type control flies were obtained, allowing a direct comparison of the sensitivities of the various mutants to DNA-damaging agents. Table 3 shows the numbers of each type after mock treatment or treatment with 6 Gy of X rays or 0.06 mM MMS. The numbers of the flies recovered were normalized for the Mendelian ratios and used to calculate the relative sensitivity of each group. In the untreated sample, the ratio of 9:4:3.4:1.2 deviates only slightly from the expected ratio of 9:3:3:1. After irradiation, a decrease in the ratios was observed for both single mutants and a very strong decrease was observed for the double mutant. At a dose of 6 Gy of X rays, the DmKu70 mutant flies showed threefold-enhanced sensitivity and the DmRAD54 mutant flies showed sevenfold-enhanced sensitivity. The radiation sensitivity of the DmRAD54/DmKu70 double mutant was increased 40-fold (see Table 3). Statistical analysis showed that the 95% confidence interval for this increase in sensitivity has a minimum of a factor of 17. Therefore, the conclusion is that DmRAD54 and Ku70 mutations cause a clear synergistic effect. This synergism in X-ray sensitivity indicates that the DmRAD54 and DmKu70 genes are involved in separate DSB repair pathways and that X-ray-inflicted damage can be repaired by both recombinational repair and NHEJ. However, a synergistic effect was not observed after treatment of the double mutant with MMS: the DmKu70 single mutant was hardly sensitive to 0.06 mM MMS (a twofold increase), the sensitivity of the DmRAD54 single mutant was increased eightfold, and an intermediate increase in sensitivity (sixfold) was observed in the DmRAD54/DmKu70 double mutant. The 95% confidence interval for the sensitivity of the double mutant to MMS is between a minimum of 3-fold and a maximum of 12-fold, indicating that the effect could be additive but is not synergistic.

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity of a DmRAD54−/−/DmKu70−/− double mutant to X rays and MMS

| Agent and dose | Genotype | Total no. of fliesa | Ratiob | Sensitivityc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Wild type | 767 | 9 | |

| DmKu70−/− | 341 | 4 | ||

| DmRAD54−/− | 294 | 3.4 | ||

| DmRAD54−/−/DmKu70−/− | 105 | 1.2 | ||

| X rays (6 Gy) | Wild type | 546 | 9 | |

| DmKu70−/− | 76 | 1.2 | 3 | |

| DmRAD54−/− | 31 | 0.5 | 7 | |

| DmRAD54−/−/DmKu70−/− | 2 | 0.03 | 40 | |

| MMS (0.06 mM) | Wild type | 373 | 9 | |

| DmKu70−/− | 73 | 1.8 | 2 | |

| DmRAD54−/− | 16 | 0.4 | 8 | |

| DmRAD54−/−/DmKu70−/− | 10 | 0.2 | 6 |

Number of flies recovered.

Ratio of the number of flies of each genotype relative to the others, with the value for wild-type (heterozygous and homozygous) flies set at 9 for comparison with the Mendelian ratio of 9:3:3:1 (wild type to DmKu70−/− to DmRAD54−/− to DmRAD54−/−/DmKu70−/− flies).

Obtained by dividing the ratio of the untreated sample by the ratio of the treated sample.

DISCUSSION

Homologous recombination is the major pathway for the repair of DSBs in yeast. The Rad54 protein, a member of the Snf2/Swi2 subfamily of DNA-dependent ATPases (21), is one of the main factors in this pathway. The analysis of mouse and chicken cells deficient in RAD54 and of a Drosophila strain with a mutation in DmRAD54 indicated that recombinational repair contributes significantly to the repair of DSBs in higher eukaryotes (5, 15, 26). A DmRAD54 null mutant shows increased larval sensitivity to ionizing radiation and MMS, defects in X-ray-induced recombination in somatic cells, and female sterility. During development the DmRAD54 gene is not essential, as evidenced by the fact that DmRAD54−/− flies can be readily obtained after heterozygous males and females are crossed. It is possible, therefore, that maternally deposited DmRAD54 mRNA contributes to the repair of exogenously induced DNA damage during early development. The increase in sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, therefore, could be underestimated.

In the past, the transposition mechanism of P transposable elements has been extensively studied in Drosophila. Recently, it has been shown that the first step in the transposition event involves the formation of two site-specific DSBs (3). Repair of these breaks can occur by recombination. To examine whether DmRAD54 plays a part in this process, we determined the somatic reversion to wild type of whd in DmRAD54+/− and DmRAD54−/− flies. Heterozygous DmRAD54 larvae hatched as adults in a normal Mendelian ratio, with a reversion frequency of one or more red spots per eye in 70% of the male flies carrying the Δ2-3 transposase gene and 85% of the females (see Table 1). The females that emerged from both crosses contain the wa allele on the second X chromosome. This mutant allele of white may be used as a template for recombination in addition to the walter element on the second chromosome. This could explain the increase in the frequency of spot-containing eyes in repair-proficient females in comparison with male flies. The effect of the DmRAD54 mutation was so great that male larvae in which P-element excision had occurred did not survive at all. The survival of female larvae was reduced to 10% in comparison with females from the same cross that did not have the transposase gene. In the flies that did hatch, the relative spot frequency was reduced fivefold compared to that in the control group. The difference in survival between males and females may be explained by the presence of the wa allele on the second X chromosome, which may give rise to a low level of DmRAD54-independent recombination in females. The results obtained in repair-deficient flies demonstrate that DmRAD54 is crucial for the repair of the DSBs after excision of a P element. Furthermore, the results suggest that NHEJ compensates only partially for the absence of DmRAD54, or only in certain cell types. P-element excision has also been studied in DmKu70 mutant flies. With the X-linked snw system, the survival of males is reduced sixfold in a Ku70-deficient background (2). For the females, the reduction in survival was less than twofold. These data suggest that in the presence of a duplicate sequence, recombinational repair is the preferred mechanism. Most likely, due to the absence of a template for recombination, the effect was much stronger in the males used by Beall and Rio (2) than in the females. The conclusion that recombinational repair is the most important repair mechanism after P-element excision is supported by studies with a mus209 mutant which is deficient in proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (22). In the absence of a functional PCNA product, mobilization of P elements results in lethality, presumably due to the essential role of PCNA in DNA repair synthesis during recombination. The prevalence of repair of DSBs by homologous recombination after P-element excision may be related to the specific nature of the breaks, which have identical 3′-single-stranded regions of 17 nucleotides. Possibly, repair of these breaks by NHEJ is not very efficient.

Cross-linking agents such as MMC and cisDDP produce a variety of DNA lesions, including cross-links. Repair of these lesions in Escherichia coli is dependent on both nucleotide excision repair (NER) and recombinational repair (12, 13). In mammalian cells the NER pathway is also involved in cross-link repair. Experiments of Bessho et al. using cell extracts or a reconstituted excision nuclease indicated that two incisions are made 22 to 28 nucleotides apart, both 5′ of the cross-link (4). In Drosophila the mei9 and mus201 mutants, which are defective in the incision step in NER, also display larval sensitivity to the cross-linking agent nitrogen mustard (8, 10). To determine if the recombinational repair pathway also participates in cross-link repair in Drosophila, wild-type and DmRAD54-deficient larvae were treated with MMC and cisDDP. The sixfold increase in larval sensitivity to both agents (Table 2) at the highest doses used demonstrates that, as in E. coli and mammals (12, 13, 15), recombinational repair is also involved in the repair of cross-links in Drosophila.

LOH was studied by using a SMART. Loss of both cn and bw marker genes on the second chromosome results in regions of mutant tissue in the eyes of adult flies, which can be scored as colorless spots. Treatment with X rays, MMS, MMC, or cisDDP resulted in a dose-dependent increase in LOH events in wild-type flies (see Fig. 2). As previously described, no induction of spots was observed after X-ray treatment of DmRAD54-deficient flies (26). Apparently, most of the X-ray-induced LOH events are due to a DmRAD54-dependent mechanism. In the absence of DmRAD54, treatment with MMS, MMC, and cisDDP resulted in a dose-dependent induction of spots in the eyes, although the spot frequencies were reduced in comparison with those in DmRAD54-proficient flies. These results indicate that the chemical agents used induce DmRAD54-dependent and -independent events. The DmRAD54-dependent events are probably due to homologous recombination, as has been previously described for ionizing radiation. DSBs are induced directly by ionizing radiation but only indirectly by MMS, MMC, and cisDDP as a consequence of repair and/or replication. It is feasible that these DSBs, or some of them, result in DmRAD54-independent LOH events.

To examine the relative contributions of homologous recombination and NHEJ in DSB repair, a DmRAD54/DmKu70 double mutant was generated. Both single mutants showed a slight increase in sensitivity to 6 Gy of X rays (seven- and threefold, respectively). The small difference in hypersensitivity for both single mutants could indicate that both mechanisms contribute more or less equally to the repair of X-ray-induced DSBs. These data, however, do not exclude the possibility that the relative contributions differ for the various cell types in the larvae. In the DmRAD54/mus309 double mutant, a clear synergistic effect was observed. At a dose of 6 Gy, the sensitivity was increased 40-fold. The small increase in radiation sensitivity seen in both single mutants in comparison with the double mutant strongly suggests overlap between recombinational repair and NHEJ at the larval stage of development. The significant increase in X-ray sensitivity in the double mutant suggests that repair by other mechanisms is not very efficient. In yeast, NHEJ is possible at a reduced level in the absence of Ku70 and involves the introduction of deletions at the site of the break (7). The same phenomenon has been observed in Drosophila by Beall and Rio (2). Another possibility is the presence of a second RAD54 homolog in Drosophila, as has been described in yeast (25, 36), which can substitute for DmRAD54.

In contrast to X rays, treatment with MMS did not result in a synergistic increase in sensitivity in the double mutant in comparison with both single mutants (see Table 3). This result differs from the results of survival experiments using Ku70−/−/RAD54−/− chicken DT40 cells, which showed a moderate sensitivity to ionizing radiation as well as to MMS in comparison with both single mutants (42). Exposure to MMS does not result in the direct induction of DSBs in DNA but possibly leads indirectly to the occurrence of DSBs as a consequence of repair or bypass of single-strand breaks during replication. Recent studies with Ku70−/−/RAD54−/− chicken DT40 cells indicated that during the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, DSBs are repaired predominantly by recombinational repair. In G1-phase cells, NHEJ is the prevalent mechanism (42). Therefore, preferential repair by homologous recombination during the S and G2 phases seems the most likely explanation for the absence of a strong synergistic increase in sensitivity in the Ku70−/−/DmRAD54−/− flies after MMS treatment. With ionizing radiation, DSBs are induced at every stage of the cell cycle, leading to a drastic increase in sensitivity in the double mutant. An alternative explanation for the absence of a drastic increase in MMS sensitivity in the double mutant could be the formation of single-strand gaps as a result of repair or replicational bypass of MMS-induced lesions. These gaps may not be a substrate for the Ku-dependent pathway, resulting in comparable MMS sensitivities in the Ku70/DmRAD54 double mutant and the DmRAD54 single mutant.

In conclusion, the Drosophila DmRAD54 gene is involved in recombinational repair of DSBs, induced by the endogenous P-element transposase or exogenous factors such as ionizing radiation, MMS, and cross-linking agents, in addition to its function in meiotic cells. The synergistic increase in X-ray sensitivity in a Ku70−/−/DmRAD54−/− double mutant and the absence of such an increase in sensitivity to MMS suggest that the stage of the cell cycle is an important factor in determining the relative contribution of each DSB repair pathway. Another important factor may be the nature of the DSB itself, as shown by the requirement for DmRAD54 in the repair of DSBs with identical 3′ overhangs, generated as a result of P-element excision.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work described in this paper was supported by the Dutch Cancer Foundation (project RUL94-774) and by the J. A. Cohen Institute, Interuniversity Research Institute for Radiopathology and Radiation Protection (IRS; project 4.4.12).

We thank Niels de Wind for critical reading of the manuscript and Koos Zwinderman for statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beall E L, Admon A, Rio D C. A Drosophila protein homologous to the human p70 Ku autoimmune antigen interacts with the P transposable element inverted repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12681–12685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beall E L, Rio D C. Drosophila IRBP/Ku p70 corresponds to the mutagen-sensitive mus309 gene and is involved in P-element excision in vivo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:921–33. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beall E L, Rio D C. Drosophila P-element transposase is a novel site-specific endonuclease. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2137–2151. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bessho T, Mu D, Sancar A. Initiation of DNA interstrand cross-link repair in humans: the nucleotide excision repair system makes dual incisions 5′ to the cross-linked base and removes a 22- to 28-nucleotide-long damage-free strand. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6822–6830. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bezzubova O, Silbergleit A, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Takeda S, Buerstedde J-M. Reduced X-ray resistance and homologous recombination frequencies in a RAD54−/− mutant of the chicken DT40 cell line. Cell. 1997;89:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulton S J, Jackson S P. Identification of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ku80 homologue: roles in DNA double-strand break rejoining and in telomeric maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4639–4648. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulton S J, Jackson S P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ku70 potentiates illegitimate DNA double-strand break repair and serves as a barrier to error-prone DNA repair pathways. EMBO J. 1996;15:5093–5103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd J B, Golino M D, Setlow R B. The mei-9a mutant of Drosophila melanogaster increases mutagen sensitivity and decreases excision repair. Genetics. 1976;84:527–544. doi: 10.1093/genetics/84.3.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd J B, Golino M D, Shaw K E, Osgood C J, Green M M. Third-chromosome mutagen-sensitive mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1981;97:607–623. doi: 10.1093/genetics/97.3-4.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd J B, Snyder R D, Harris P V, Presley J M, Boyd S F, Smith P D. Identification of a second locus in Drosophila melanogaster required for excision repair. Genetics. 1982;100:239–257. doi: 10.1093/genetics/100.2.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu G. Double strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24097–24100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole R S. Repair of DNA containing interstrand crosslinks in Escherichia coli: sequential excision and recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:1064–1068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.4.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole R S, Sinden R R. Repair of cross-linked DNA in Escherichia coli. Basic Life Sci. 1975;5B:487–495. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-2898-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engels W R, Johnson-Schlitz D M, Eggleston W B, Sved J. High-frequency P element loss in Drosophila is homolog dependent. Cell. 1990;62:515–525. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Essers J, Hendriks R W, Swagemakers S M, Troelstra C, de Wit J, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers J H, Kanaar R. Disruption of mouse RAD54 reduces ionizing radiation resistance and homologous recombination. Cell. 1997;89:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldmann H, Winnacker E L. A putative homologue of the human autoantigen Ku from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12895–12900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FlyBase Consortium. 1998. FlyBase—a Drosophila Database, http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/ Nucleic Acids Res. 26:85–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Siede W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghabrial A, Ray R P, Schüpbach T. okra and spindle-B encode components of the RAD52 DNA repair pathway and affect meiosis and patterning in Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2711–2723. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gloor G B, Nassif N A, Johnson-Schlitz D M, Preston C R, Engels W R. Targeted gene replacement in Drosophila via P element-induced gap repair. Science. 1991;253:1110–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1653452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Helicases: amino acid sequence comparison and structure-function relationships. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:419–429. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson D S, Glover D M. Chromosome fragmentation resulting from an inability to repair transposase-induced DNA double-strand breaks in PCNA mutants of Drosophila. Mutagenesis. 1998;13:57–60. doi: 10.1093/mutage/13.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrmann G, Lindahl T, Schar P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae LIF1: a function involved in DNA double-strand break repair related to mammalian XRCC4. EMBO J. 1998;17:4188–4198. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacoby D B, Wensink P C. Yolk protein factor 1 is a Drosophila homolog of Ku, the DNA-binding subunit of a DNA-dependent protein kinase from humans. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11484–11491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein H L. RDH54, a RAD54 homologue in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is required for mitotic diploid-specific recombination and repair and for meiosis. Genetics. 1997;147:1533–1543. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.4.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kooistra R, Vreeken K, Zonneveld J B, de Jong A, Eeken J C, Osgood C J, Buerstedde J-M, Lohman P H M, Pastink A. The Drosophila melanogaster RAD54 homolog, DmRAD54, is involved in the repair of radiation damage and recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6097–6104. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsley D L, Zimm G G. The genome of Drosophila melanogaster. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milne G T, Jin S, Shannon K B, Weaver D T. Mutations in two Ku homologs define a DNA end-joining repair pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4189–4198. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.New J H, Sugiyama T, Zaitseva E, Kowalczykowski S C. Rad52 protein stimulates DNA strand exchange by Rad51 and replication protein A. Nature. 1998;391:407–410. doi: 10.1038/34950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nickoloff J A, Hoekstra M F. Double-strand break and recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Nickoloff J A, Hoekstra M F, editors. DNA damage and repair. I. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1998. pp. 335–362. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Hare K, Rubin G M. Structures of P transposable elements and their sites of insertion and excision in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Cell. 1983;34:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petrini J H J, Bressan D A, Yao M S. The RAD52 epistasis group in mammalian double strand break repair. Semin Immunol. 1997;9:181–188. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petukhova G, Stratton S, Sung P. Catalysis of homologous DNA pairing by yeast Rad51 and Rad54 proteins. Nature. 1998;393:91–94. doi: 10.1038/30037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson H M, Preston C R, Phillis R W, Johnson-Schlitz D M, Benz W K, Engels W R. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;118:461–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schar P, Herrmann G, Daly G, Lindahl T. A newly identified DNA ligase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in RAD52-independent repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1912–1924. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinohara A, Ogawa T. Stimulation by Rad52 of yeast Rad51-mediated recombination. Nature. 1998;391:404–407. doi: 10.1038/34943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shinohara M, Shita-Yamaguchi E, Buerstedde J-M, Shinagawa H, Ogawa H, Shinohara A. Characterization of the roles of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD54 gene and a homologue of RAD54, RADH54/TID1, in mitosis and meiosis. Genetics. 1997;147:1545–1556. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.4.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siede W, Friedl A A, Dianova I, Eckardt-Schupp F, Friedberg E C. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ku autoantigen homologue affects radiosensitivity only in the absence of homologous recombination. Genetics. 1996;142:91–102. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sung P. Catalysis of ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange by yeast RAD51 protein. Science. 1994;265:1241–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.8066464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung P. Function of yeast Rad52 protein as a mediator between replication protein A and the Rad51 recombinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28194–28197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sung P. Yeast Rad55 and Rad57 proteins form a heterodimer that functions with replication protein A to promote DNA strand exchange by Rad51 recombinase. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1111–1121. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.9.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takata M, Sasaki M S, Sonoda E, Morrison C, Hashimoto M, Utsumi H, Yamguchi-Iwai Y, Shinohara A, Takeda S. Homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways of DNA double strand break repair have overlapping roles in the maintainance of chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:5497–5508. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teo S-H, Jackson S P. Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA ligase IV: involvement in DNA double-strand break repair. EMBO J. 1997;16:4788–4795. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsukamoto Y, Ikeda H. Double-strand break repair mediated by DNA end-joining. Genes Cells. 1998;3:135–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson T E, Grawunder U, Lieber M R. Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates non-homologous DNA end joining. Nature. 1997;388:495–498. doi: 10.1038/41365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]