Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the topmost causes of death in males in Saudi Arabia. In females, it was also within the top five cancer types. CRC is heterogeneous in terms of pathogenicity and molecular genetic pathways. It is very important to determine the genetic causes of CRC in the Saudi population. BRAF is one of the major genes involved in cancers, it participates in transmitting chemical signals from outside the cells into the nucleus of the cells and it is also shown to participate in cell growth. In this study, we mapped the spectrum of BRAF mutations in 100 Saudi patients with CRC. We collected tissue samples from colorectal cancer patients, sequenced the BRAF gene to identify gene alterations, and analyzed the data using different bioinformatics tools. We designed a three-dimensional (3D) homology model of the BRAF protein using the Swiss Model automated homology modeling platform to study the structural impact of these mutations using the Missense3D algorithm. We found six mutations in 14 patients with CRC. Four of these mutations are being reported for the first time. The novel frameshift mutations observed in CRC patients, such as c.1758delA (E586E), c.1826insT (Q609L), c.1860insA and c.1860insA/C (M620I), led to truncated proteins of 589, 610, and 629 amino acids, respectively, and potentially affected the structure and the normal functions of BRAF. These findings provide insights into the molecular etiology of CRC in general and to the Saudi population. BRAF genetic testing may also guide treatment modalities, and the treatment may be optimized based on personalized gene variations.

Keywords: BRAF gene, Colorectal cancer, Mutational Screening, Nucleotide variants, Swiss Model, Homology modeling

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the most common cancer type in men and the third most common cancer type in women in Saudi Arabia (Alsanea et al., 2015). Worldwide, it is also one of the major cancers and the leading cause of death, with 1,849,518 new cases and 880,792 deaths approximately every year (Caputo et al., 2019). Geographically, CRC incidence and mortality are more common in industrialized countries (Bray et al., 2018). However, many other countries, especially those located in Latin America, Asia, and Eastern Europe, have seen higher incidence and mortality rates of CRC (Caputo et al., 2019). Currently, many CRC cases are diagnosed at an early age due to diagnosis improvement and are immediately treated with curative surgery; however, a very high number of CRC patients progressively develop synchronous or metachronous metastatic disease, which is very alarming, with a five-year survival rate of only nearly 13% (American Cancer Society, 2016). Due to the advancement of new therapeutic approaches, the overall mortality rates are decreasing worldwide; however, the mortality rates in the young population (<50 years) are rising rapidly (Lucente and Polansky, 2018, Ducreux et al., 2019). In the United States, the incidence of new CRC cases has surged by approximately 22% in recent years since 2000, in less than 50 years of age population group (Siegel et al., 2017). The number of CRC cases has been constantly declining (32% reduction in new cases) in more than 50 years of age, which may be due to different factors such as increased and improved screening strategies and removal of precancerous polyps at an early stage before they develop cancerously (Siegel et al., 2017, Bailey et al., 2015). The other problem currently is that not only is the young population record more incidences of CRC, but the cancer is more often diagnosed at a more advanced stage (Lucente and Polansky, 2018). The causes of these increase in number are still subject of debate and no conclusive evidence has been served but the broadly known risk factors include the genetic and familial causes (the patients with a family history of cancer shown to have more risk associated with developing cancer than others), as the hereditary forms of colon cancer such as Lynch syndrome (Provenzale et al., 2018). Although the occurrence of CRC is approximately 20% of all CRC cases in the context of family history, it is still very low and only about 2%–4% have been described in the context of hereditary cancer syndromes (Provenzale et al., 2018). The second most common factor maybe be related to lifestyle and food choices in the young population. In the past decade, lifestyle and food habits have changed drastically. Obesity (high BMI index) coupled with processed food, red meat and alcohol intake, tobacco smoking, and a sedentary lifestyle also contributes to an increased risk of developing CRC in the younger population (Bailey et al., 2015). Therefore, more scientific investigations are needed to conclusively determine the effect of the shift in demographics in increasing CRC in different age groups. Currently, early detection seems to be the most effective in reducing mortality rates, especially when a patient reports symptoms such as melena, abdominal and pelvic pain, sudden weight loss, alteration in bowel movements, and anemic conditions (Ahnen et al., 2014). Clinicians should be more suspicious in these conditions to start an early investigation to rule out CRC, and patients should also be more educated to report such symptoms in earlier stages (Lucente and Polansky, 2018).

The advent of new molecular biology techniques has led us to study cancers at the molecular level. This advancement has enhanced our knowledge of cancers at the molecular level because now we know that more genetic and epigenetic events are involved in tumorigenesis, which has enabled us to choose and develop therapeutics more accurately (Clarke and Kopetz, 2015). BRAF (proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase) is an important molecular genetic marker that is currently used for CRC diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment modalities (Kudryavtseva et al., 2016).

In this study, we aimed to identify the BRAF mutational spectrum in the Saudi population to determine the genetic heterogeneity associated with CRC and to better understand the disease manifestation in the local population.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection and extraction of DNA

We collected 100 tumor tissue samples from CRC patients. Complete clinical information was obtained from patients and clinicians. The tissue samples were transported to the CEGMR and stored in a bio bank until further molecular analysis. The study was approved by the ethical committee of CEGMR, King Abdulaziz University, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants of the study. Each patient sample was given unique ID and kept in secured place.

2.2. DNA extraction, sequencing, and analysis of BRAF gene

DNA was extracted from tumor tissue of 100 CRC samples using the DNeasy® kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The quantity of DNA was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. The quality of DNA was assessed by running it through a 1% agarose gel in a horizontal gel tank apparatus and visualized under a UV illuminator. After confirmation of the quantity and quality of DNA, we sequenced the BRAF gene using Big Dye Terminator® on an ABI 3730xl sequencer. To read sequence peaks, we used the BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor Version 7.2.5.

2.3. BRAF three-dimensional structure and mutation analysis

A three-dimensional (3D) homology model of the BRAF protein was designed using the Swiss model automated homology modeling platform (Waterhouse et al., 2018). The FASTA sequence of BRAF was downloaded from the UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProt ID: P15056, conforming to a 766 amino acid transcript (Ensembl ID: ENSMUSG00000002413) (The UniProt Consortium, 2017). A template search with BLAST and HHblits was performed against the SWISS-MODEL template library (SMTL, last update: 2021-05-26, last included PDB release: 2021-05-21). The target sequence was searched against the primary amino acid sequence contained in the SMTL (Bienert et al., 2017). An initial HHblits profile was built (Steinegger et al., 2019, Mirdita et al., 2017) and was searched against all profiles of the SMTL. A total of 5350 templates were identified. Models were built based on target-template alignment using ProMod3 (Studer et al., 2021). The global and per-residue model quality was assessed using the QMEAN scoring function (Studer et al., 2020). The MolProbity score was assessed for the BRAF homology model using a previously described method (Chen et al., 2010). The Ramachandran plot of the BRAF homology model was used to identify residues in the favored region, outlier region, rotamer outliers, C-beta deviations, bad bonds, and bad angles (Ramachandran et al., 1963). The quaternary structure annotation of the template was used to model the oligomeric form of the target sequence based on a previously described method (Bertoni et al., 2017).

2.4. BRAF mutation analysis

The impact of each mutation listed in able 1 on the BRAF homology model was evaluated by investigating the structural features available in the Missense3D algorithm (Ittisoponpisan et al., 2019) like disulfide bond breakage, buried proline introduction, clash, buried hydrophilic residue introduction, buried charge introduction, secondary structure alteration, buried charge switch, allowed phi/psi, buried charge replacement, buried glycine replacement, buried H-bond breakage, buried salt bridge breakage, cavity alteration, buried/exposed switch, crest replacement, glycine, and replacement in a bend.

3. Results

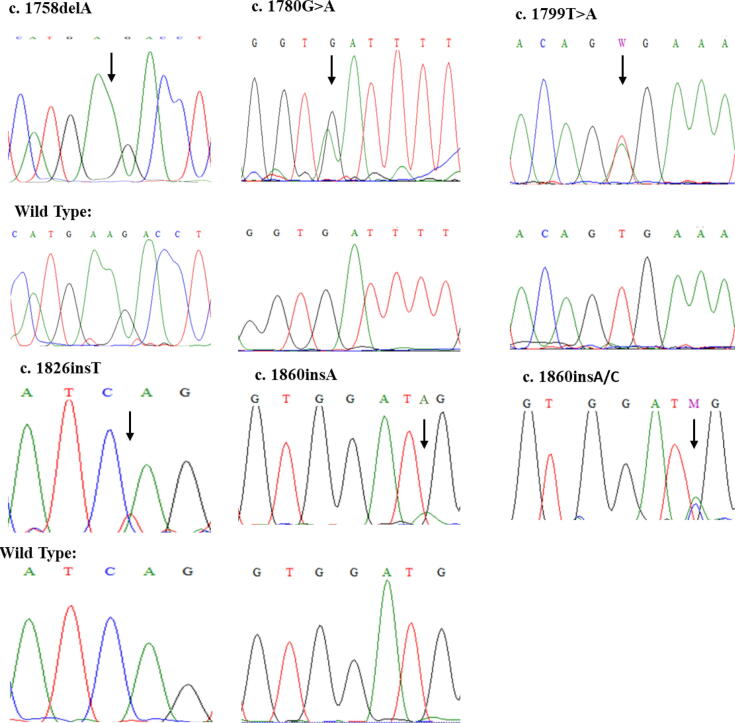

Sanger sequencing revealed many known and novel mutations in the Saudi population. The results of the sequencing of the BRAF gene are summarized in Table 1, and representative chromatograms are shown in Fig. 1. Of the 100 CRC samples, we found mutations in 14 samples (14%). The most common mutation was at c.1799 T > A (V600E) in five samples. Second, we identified c.1758delA in four patients. Third, a couple of patients had a mutation at c.1860insA/C. Furthermore, at fourth, fifth, and sixth we had a mutation in one patient each at c.1780G > A; D594N, c.1826insT, and c.1860insA, respectively. The age of the patients, Gender and tumor location are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Spectrum of BRAF gene mutations in colorectal cancer in the Saudi population.

| S. No | No. of patients | Nucleotide change | Protein change | Reported or Novel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | c. 1758delA | p. E586E | Novel. Resulting in frameshift and truncated protein of 589 amino acids. |

| 2 | 1 | c. 1780 G > A | p. D594N | Reported (Zheng et al., 2015) |

| 3 | 5 | c. 1799 T > A | p. V600E | Reported (Davies et al., 2002) |

| 4 | 1 | c. 1826insT | p. Q609L | Novel. Resulting in frameshift and truncated protein of 610 amino acids. |

| 5 | 1 | c. 1860insA | p. M620I | Novel. Resulting in frameshift and truncated protein of 629 amino acids. |

| 6 | 2 | c. 1860insA/C | p. M620I | Novel. Resulting in frameshift and truncated protein of 629 amino acids. |

Fig. 1.

Sanger’s sequencing chromatograms of 6 mutations identified in this study.

Table 2.

Tumor location, age and gender of the patients with BRAF gene mutations.

| S. No. | Sample ID | Mutation | Age | Gender | Tumor Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CRC-388 | p. E586E | 72 | male | Right |

| 2 | CRC-1296 | p. E586E | 76 | female | Left |

| 3 | CRC-82 | p. E586E | 58 | female | Left |

| 4 | CRC-524 | p. E586E | 78 | male | Rectal |

| 5 | CRC-210 | p. D594N | 42 | female | Right |

| 6 | CRC-706 | p. V600E | 82 | male | Right |

| 7 | CRC-778 | p. V600E | 69 | female | Left |

| 8 | CRC-450 | p. V600E | 75 | female | Right |

| 9 | CRC-4204 | p. V600E | 50 | female | Right |

| 10 | CRC-12 | p. V600E | 63 | male | Right |

| 11 | CRC-462 | p. Q609L | 53 | female | Rectal |

| 12 | CRC-2162 | p. M620I | 46 | male | Right |

| 13 | CRC-2160 | p. M620I | 54 | male | Left |

| 14 | CRC-440 | p. M620I | 60 | female | Rectal |

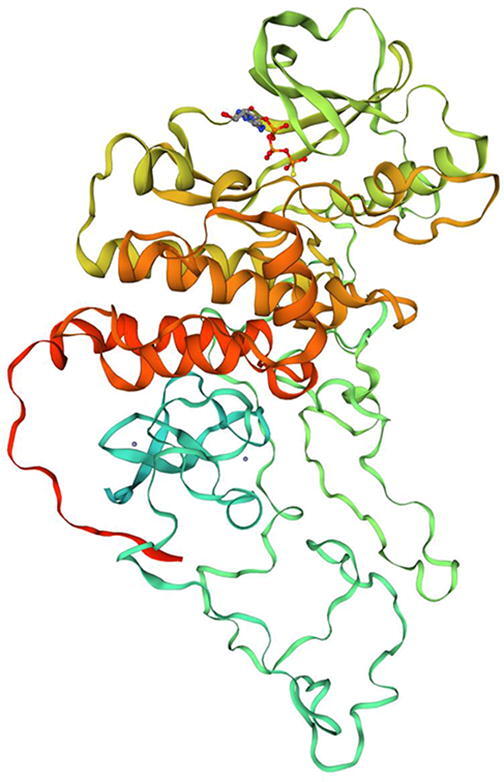

To generate a homology model for the wild-type (WT) BRAF protein, the target sequence obtained from UniProt was searched using BLAST against the primary amino acid sequence contained in the SMTL (Camacho et al., 2009). An initial HHblits profile was built (Steinegger et al., 2019) and was searched against all profiles of the SMTL. However, 50 suitable templates were found for homology modeling of BRAF. A further 5,231 templates were found that were considered to be less suitable for modeling than the filtered list. The BRAF homology model was built using the top protein template, 6nyb.1. A tertiary complex of BRAF/MEK1/14–3-3 with an MEK inhibitor (Park et al., 2019). The wild type 3D homology model of BRAF is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

BRAF Homology Model. A three-dimensional (3D) homology model of the BRAF protein was designed using the Swiss Model homology modeling platform.

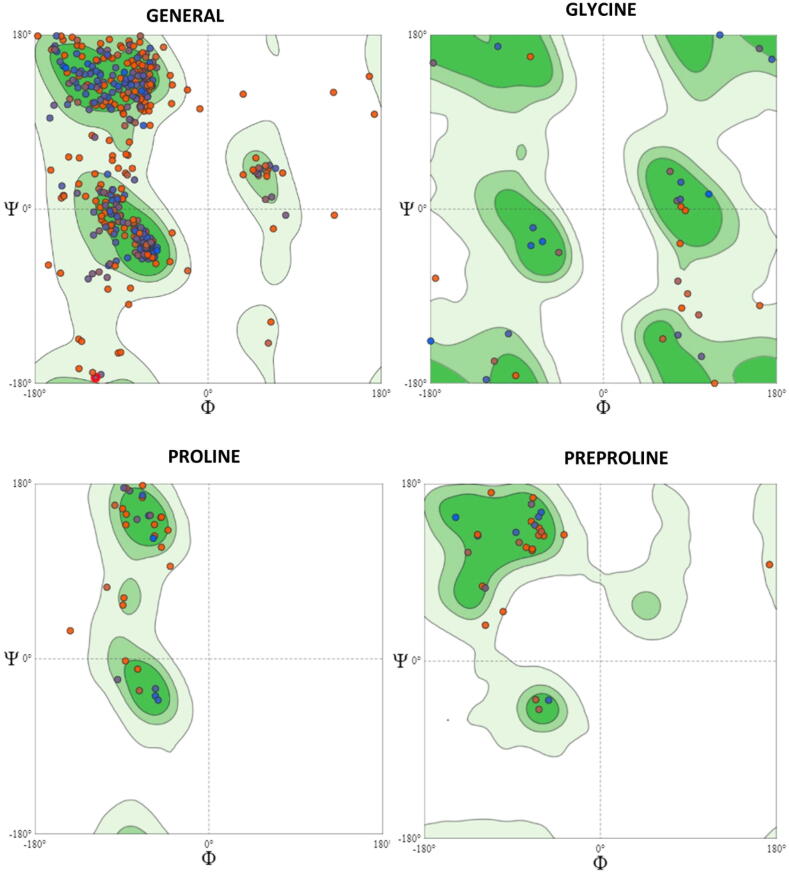

The MolProbity Score for the BRAF model was 2.2, with a Clash Score of 3.25. The Ramachandran plot of the BRAF homology model showed that 84.2% of residues were in the favored region, 3.97% were in the outlier region, rotamer outliers were 3.81%, C-beta deviations were 9, bad bonds were 10 out of 4140, and bad angles were 62 out of 5578 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Ramachandran Plots for BRAF Homology Model. The Mol Probity Score for the BRAF model is 2.2 with a Clash Score of 3.25. Ramachandran plot of BRAF homology model showed that 84.2% of residues were in the favored region, 3.97% were in the outlier region, Rotamer Outliers were 3.81%, C-Beta Deviations were 9, Bad Bonds were 10 out of 4140, and Bad Angles were 62 out of 5578.

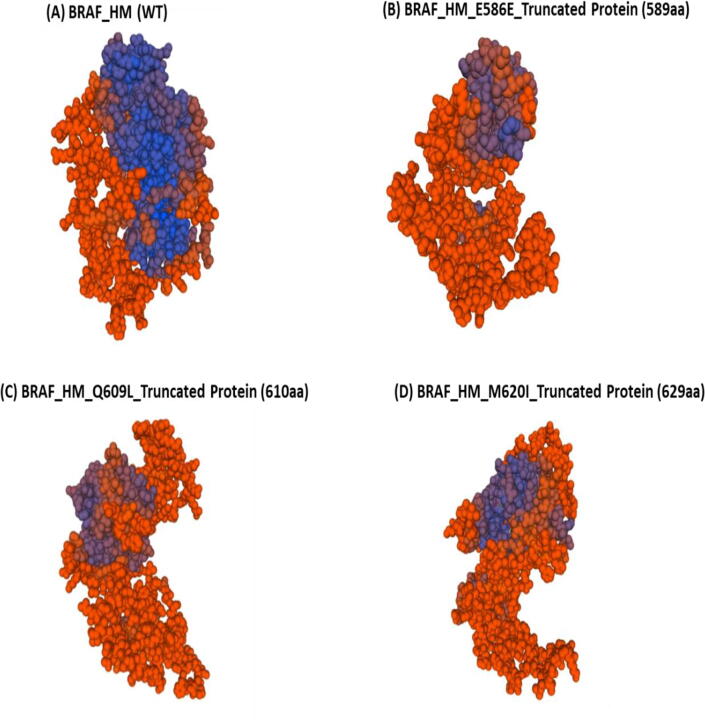

The BRAF homology model was tested using the well-known V600E mutation using the Missense 3D algorithm to assess the accuracy of the model. A damaging effect was predicted in the BRAF structure by Missense 3D such as F01: disulfide breakage: N|F02: buried Pro introduced: N|F03:Clash: N|F04:Buried hydrophilic introduced: Y|F05:Buried charge introduced: Y|F06:Secondary structure altered: N|F07:Buried charge switch: N|F08:Disallowed phi/psi: N|F09:Buried charge replaced: N|F10:Buried Gly replaced: N|F11:Buried H-bond breakage: N|F12:Buried salt bridge breakage: N|F13:Cavity altered: N|F14:Buried / exposed switch: N|F15:Cis pro replaced: N|F16:Gly in a bend: N|. However, no structural changes were observed in the BRAF homology model of the mutation D595N. On the other hand, the frameshift mutations observed in CRC patients, such as E586E, Q609L, and M620I, led to truncated proteins 589aa, 610aa, and 629 aa, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Homology models for normal and truncated BRAF. The structures of (A) wild type and (B - C) mutant homology models. The frame-shift mutations observed in the CRC patients such as E586E, Q609L, and M620I led to truncated proteins 589aa, 610aa, and 629aa respectively.

4. Discussion

Colorectal cancer is a heterogeneous disease and can be characterized by various genetic and epigenetic alterations. Many pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of CRC. The first pathway is called the classic or adenoma-to-carcinoma pathway or chromosomal instability pathway and occurs most widely and is caused by loss of APC with or without p53 tumor suppressor genes, leading to chromosomal instability (Vogelstein et al., 1988). The second pathway involves disruption of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, as widely seen in germline mutations of MMR genes in Lynch syndrome (Thibodeau et al., 1998). The third pathway is the serrated/methylator pathway, in which BRAF plays a major role (Weisenberger et al., 2006). This pathway involves the silencing of important tumor suppressor genes through the methylation of CpG islands and is also referred to as CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) tumors (Clarke and Kopetz, 2015).

BRAF (B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase) is a member of the rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF) family that regulates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway, which affects cell division, differentiation, and secretion (Kudryavtseva et al., 2016). In the MAPK pathway, BRAF acts downstream of KRAS. RAF activation in normal cells is a very complex process that requires frequent dephosphorylation events exhibiting regulatory features, binding of proteins and ligands, and conformational changes (Avruch et al., 2001). BRAF mutations cause the transformation of epithelia into serrated adenomas at an early stage of carcinogenesis (Barras, 2015). Hence, we considered oncogenic driver genes. BRAF constitutive activation induces a disturbance in the polarity of epithelial cells by activating Myc expression, and therefore plays a vital role in CRC progression and metastasis (Magudia et al., 2012). Several studies have shown that BRAF mutations are present in about 5–15% of all CRC cases and most mutations appear in the right-sided colon cancer (Chiu et al., 2018).

In our study, we also found BRAF mutations in 14% of patients with CRC. Of these, 5% of the mutations were only found in the V600E position, which is considered to be a hot spot of the BRAF gene mutations, as most previous studies have also found the same mutation and have extensively studied this mutation (Caputo et al., 2019). These mutations are more commonly found in females than in males and present more on the right side of the colon. In our study we also found V600E more in females, where we have mutation in three female as compared to two males. The tumor was also located more on right side of colon (4 patients had tumor on right side of colon whereas one had on left side). The second most common mutation was the deletion of A at c.1758 bp, resulting in frameshift and truncated protein of 589 amino acids only. We found this mutation in 4 patients. At third place we found heterozygous insertion of A/C at c.1860 bp in two patients and in one patient we found only insertion of A. This insertion leads to frameshift and stop codon after 629aa. We found a mutation in a patient at c.1780G > A (D594N). This mutation has been reported and studied previously in colon cancer patients (Zheng et al., 2015). Then we found a mutation in a patient at c.1826insT, that results in frame shift and leads to truncated protein of 610 amino acids.

The mutations c.1758delA, c.1826insT, c.1860insA and 1860insA/C are novel and we are reporting them for the first time in CRC patients. Therefore, we confirmed using Homology modeling of BRAF with frameshift mutations E586E, Q609L, and M620I and found that these mutations were damaging and led to truncated and defective BRAF proteins. These frameshift mutations thus predict the worst clinical prognosis, impaired response to therapy, and other clinical consequences in patients with CRC. To the best of our knowledge, our research has led to many novel mutations in BRAF gene in CRC patients, and further studies are needed to correlate these mutations with treatment outcomes.

5. Conclusion

Early and better-quality diagnosis can save the life of patients with CRC; therefore, it is very important to diagnose CRC at an early stage of the disease. BRAF gene alterations and other precise molecular and genetic profiling should also be investigated as soon as the patient is diagnosed with CRC. The accurate identification of known and novel mutations and their clinical implications are warranted to predict the prognosis and determine personalized treatment options. In our research study we found novel mutations in BRAF gene at c.1758delA, c.1826insT, c.1860insA and c.1860insA/C in CRC patients from Saudi Arabia. However, further in vitro and in vivo experiments are warranted to correlate the newly identified mutations in our study with different drug regimens and survival outcomes.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant No. (DF-527-142-1441). The authors, therefore, gratefully acknowledge DSR technical and financial support.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Ahnen D.J., Wade S.W., Jones W.F., Sifri R., Mendoza Silveiras J., Greenamyer J., Guiffre S., Axilbund J., Spiegel A., You Y.N. The increasing incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer: a call to action. Mayo. Clinic Proc. 2014;89(2):216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsanea N., Abduljabbar A.S., Alhomoud S., Ashari L.H., Hibbert D., Bazarbashi S. Colorectal cancer in Saudi Arabia: incidence, survival, demographics and implications for national policies. Ann. Saudi Med. 2015;35(3):196–202. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2015.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society, 2016. Cancer Facts & Figures; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA.

- Avruch J., Khokhlatchev A., Kyriakis J.M., Luo Z., Tzivion G., Vavvas D., Zhang X.F. Ras activation of the Raf kinase: tyrosine kinase recruitment of the MAP kinase cascade. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 2001;56:127–155. doi: 10.1210/rp.56.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C.E., Hu C.Y., You Y.N., Bednarski B.K., Rodriguez-Bigas M.A., Skibber J.M., Cantor S.B., Chang G.J. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975–2010. JAMA. Surgery. 2015;150(1):17–22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barras D. BRAF Mutation in Colorectal Cancer: An Update. Biomarkers Cancer. 2015;7(Suppl 1):9–12. doi: 10.4137/BIC.S25248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni M., Kiefer F., Biasini M., Bordoli L., Schwede T. Modeling protein quaternary structure of homo- and hetero-oligomers beyond binary interactions by homology. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09654-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienert S., Waterhouse A., de Beer T.P., Tauriello G., Studer G., Bordoli L., Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository - new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D313–D319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C., Coulouris G., Avagyan V., Ma N., Papadopoulos J., Bealer K., Madden T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinf. 2009;10(1):421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo F., Santini C., Bardasi C., Cerma K., Casadei-Gardini A., Spallanzani A. BRAF-Mutated Colorectal Cancer: Clinical and Molecular Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(21):5369. doi: 10.3390/ijms20215369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen V.B., Arendall W.B., Headd J.J., Keedy D.A., Immormino R.M., Kapral G.J., Murray L.W., Richardson J.S., Richardson D.C. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66(1):12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu J.W., Krzyzanowska M.K., Serra S., Knox J.J., Dhani N.C., Mackay H., Hedley D., Moore M., Liu G., Burkes R.L., Brezden-Masley C., Roehrl M.H., Craddock K.J., Tsao M.-S., Zhang T., Yu C., Kamel-Reid S., Siu L.L., Bedard P.L., Chen E.X. Molecular Profiling of Patients With Advanced Colorectal Cancer: Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Experience. Clin. Colorectal Cancer. 2018;17(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C.N., Kopetz E.S. BRAF mutant colorectal cancer as a distinct subset of colorectal cancer: clinical characteristics, clinical behavior, and response to targeted therapies. J. Gastrointestinal Oncol. 2015;6(6):660–667. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H., Bignell G.R., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S., Teague J. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducreux M., Chamseddine A., Laurent-Puig P., Smolenschi C., Hollebecque A., Dartigues P., Samallin E., Boige V., Malka D., Gelli M. Molecular targeted therapy of BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer. Therap. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2019;11 doi: 10.1177/1758835919856494. 175883591985649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittisoponpisan S., Islam S.A., Khanna T., Alhuzimi E., David A., Sternberg M. Can Predicted Protein 3D Structures Provide Reliable Insights into whether Missense Variants Are Disease Associated? J. Mol. Biol. 2019;431(11):2197–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtseva A.V., Lipatova A.V., Zaretsky A.R., Moskalev A.A., Fedorova M.S., Rasskazova A.S., Shibukhova G.A., Snezhkina A.V., Kaprin A.D., Alekseev B.Y., Dmitriev A.A., Krasnov G.S. Important molecular genetic markers of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(33):53959–53983. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucente P., Polansky M. Colorectal cancer rates are rising in younger adults. JAAPA: Off. J. Am. Acad. Phys. Assistants. 2018;31(12):10–11. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000547755.61546.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magudia K., Lahoz A., Hall A. K-Ras and B-Raf oncogenes inhibit colon epithelial polarity establishment through up-regulation of c-myc. J. Cell Biol. 2012;198(2):185–194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201202108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirdita M., von den Driesch L., Galiez C., Martin M.J., Söding J., Steinegger M. Uniclust databases of clustered and deeply annotated protein sequences and alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D170–D176. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E., Rawson S., Li K., Kim B.W., Ficarro S.B., Pino G.G., Sharif H., Marto J.A., Jeon H., Eck M.J. Architecture of autoinhibited and active BRAF-MEK1-14-3-3 complexes. Nature. 2019;575(7783):545–550. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1660-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzale D., Gupta S., Ahnen D.J., Markowitz A.J., Chung D.C., Mayer R.J. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Colorectal Cancer Screening, Version 1.2018. J. Natl. Comprehensive Cancer Netw.: JNCCN. 2018;16(8):939–949. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran G.N., Ramakrishnan C., Sasisekharan V. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J. Mol. Biol. 1963;7(1):95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(63)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fedewa S.A., Ahnen D.J., Meester R., Barzi A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2017;67(3):177–193. doi: 10.3322/caac.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinegger M., Meier M., Mirdita M., Vöhringer H., Haunsberger S.J., Söding J. HH-suite3 for fast remote homology detection and deep protein annotation. BMC Bioinf. 2019;20:473. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-3019-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer G., Rempfer C., Waterhouse A.M., Gumienny G., Haas J., Schwede T. QMEANDisCo - distance constraints applied on model quality estimation. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:1765–1771. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer G., Tauriello G., Bienert S., Biasini M., Johner N., Schwede T., Schneidman-Duhovny D. ProMod3 - A versatile homology modelling toolbox. PLOS Comp. Biol. 2021;17(1):e1008667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium, 2017. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D158–D169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Thibodeau S.N., French A.J., Cunningham J.M., Tester D., Burgart L.J., Roche P.C. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer: different mutator phenotypes and the principal involvement of hMLH1. Cancer Res. 1998;58(8):1713–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B., Fearon E.R., Hamilton S.R., Kern S.E., Preisinger A.C., Leppert M., Smits A.M.M., Bos J.L. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. New England J. Med. 1988;319(9):525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S., Studer G., Tauriello G., Gumienny R., Heer F.T., de Beer T.A.P., Rempfer C., Bordoli L., Lepore R., Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisenberger D.J., Siegmund K.D., Campan M., Young J., Long T.I., Faasse M.A., Kang G.H., Widschwendter M., Weener D., Buchanan D., Koh H., Simms L., Barker M., Leggett B., Levine J., Kim M., French A.J., Thibodeau S.N., Jass J., Haile R., Laird P.W. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 2006;38(7):787–793. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G., Tseng L.-H., Chen G., Haley L., Illei P., Gocke C.D., Eshleman J.R., Lin M.-T. Clinical detection and categorization of uncommon and concomitant mutations involving BRAF. BMC cancer. 2015;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1811-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]