Abstract

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is associated with neuronal growth and reduced BDNF has been implicated in depression. A recent meta-analysis documented reliable effects of exercise on BDNF levels (Szuhany et al., 2015); although, few studies included participants with mental health conditions. In this study, we examine whether increased exercise was associated with enhanced BDNF response in depressed patients, and whether this change mediated clinical benefits. A total of 29 depressed, sedentary participants were randomized to receive either behavioral activation (BA) plus an exercise or stretching prescription. Blood was collected prior to (resting BDNF levels) and following an exercise test (pre- to post-exercise BDNF change) at four points throughout the study. Participants also completed depression and exercise assessments. BDNF increased significantly across all assessment points (p<0.001, d=0.83). Changes in BDNF from pre- to post-exercise were at a moderate effect for the interaction of exercise and time which did not reach significance (p=0.13, d=0.53), with a similar moderate, non-significant effect for resting BDNF levels (p=0.20, d=0.49). Contrary to hypotheses, change in resting BDNF or endpoint change in BDNF was not associated with changes in depression. In an intervention that included active treatment (BA), we could not verify an independent predictive effect for changes in BDNF across the trial. Overall, this study adds to the literature showing reliable effects of acute exercise on increasing BDNF and extends this research to the infrequently studied depressed population, but does not clarify the mechanism behind exercise benefits for depression.

Clinical Trials Registry (clinicaltrials.gov): NCT02176408, “Efficacy of Adjunctive Exercise for the Behavioral Treatment of Major Depression”

Keywords: brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF, depression, exercise, physical activity

Introduction

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a protein largely found in certain brain regions, such as the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and cerebellum, as well as in the peripheral nervous system. BDNF plays a role in neuronal growth and differentiation and in reducing neuro-degeneration and increasing neuroplasticity. Given its role in neuronal growth, studies have shown that decreased levels of BDNF are associated with impairments in memory consolidation, storage, and long-term memory (Cirulli et al., 2004; Roig et al., 2013).

As BDNF and exercise have similar effects on improving cognition (McMorris and Hale, 2012; Smith et al., 2010), BDNF may be the pathway by which exercise exerts its effects (Erickson et al., 2012). A recent meta-analysis aiming to explicate the first component of this pathway--the effect of exercise on BDNF—showed BDNF elevations after a single bout of exercise and after a program of regular exercise (Szuhany et al., 2015). Specifically, results indicated a moderate effect of a acute exercise on an increase in pre- to post-exercise BDNF, which was replicated in a meta-analysis of 55 studies of healthy adults (Dinoff et al., 2017). This pre- to post-exercise BDNF increase was intensified following a program of regular exercise. Resting BDNF also increased following regular exercise, but at a small effect size. Results from this study suggest reliable BDNF increases following both acute and regular exercise.

Concerning the second half of the potential causal pathway between exercise and depression, few studies have examined whether BDNF changes from exercise predict changes in depression symptoms. Few studies in the meta-analysis included participants with psychiatric conditions, and only three included depressed participants (Gustafsson et al., 2009; Laske et al., 2010; Toups et al., 2011). A recent meta-analysis only identified six studies of exercise effects on resting BDNF in patients with MDD (Dinoff et al., 2018). However, within these studies, conflicting results of the effect of BDNF change on depression exist; some suggest BDNF increases in depressed patients as depression improves (Gourgouvelis et al., 2018) and some suggest BDNF is not a factor in depression changes (Toups et al., 2011).

Yet, other research has implicated BDNF in pathways affecting depression. For example, studies have indicated that depressed patients show lower resting levels of serum and plasma BDNF than healthy controls (Bocchio-Chiavetto et al., 2010; Brunoni et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2007). Additionally, meta-analyses and reviews (Russo-Neustadt and Chen, 2005; Sen et al., 2008) have shown that antidepressant treatment significantly increases BDNF from pre- to post-treatment in depressed patients, though the relative degree of increase depends on the specific antidepressant (Zhou et al., 2017).

In the current study, we evaluate the change in BDNF after exercise in depressed outpatients and examine the link between these changes and treatment outcome. Specifically, this was a secondary analysis of possible mediating effects of BDNF in a pilot randomized controlled trial which examined the effects of exercise in combination with psychosocial treatment on depression symptoms (Szuhany and Otto, 2019). In accordance with meta-analytic results, we hypothesized that resting BDNF levels would increase following an exercise program and that the pre- to post-increase in BDNF would intensify over time. We also hypothesized that the increases in resting and pre- to post-exercise BDNF levels would be associated with the degree of improvement in depression symptoms.

Material and Methods

Participants

Participants were sedentary adults ages 18–65 with a principal diagnosis of MDD or persistent depressive disorder (PDD) with a current major depressive episode. As this was a secondary analysis, screening procedures and extended psychiatric and medical inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in greater detail elsewhere (Szuhany and Otto, 2019). Briefly, exclusion criteria were designed for safety (e.g., low to moderate exercise risk; low suicide risk) and generalizability (e.g., no concurrent cognitive behavioral therapy, no history of psychosis or bipolar disorder). Individuals taking psychotropic medications at ≥8 weeks stable dose prior to entry were included. Participants provided informed consent after procedures were fully explained. All procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board and carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

A total of 29 participants were able to provide at least 1 blood sample. Two individuals were excluded from the full sample (n=31) due to inability to draw blood. Of these 29 participants, 15 provided samples pre- and post-exercise across all four time points. Other participants dropped out prior to study completion (n=10) or were unable to provide a sample on a visit (n=4). All 29 participants were included in intent-to-treat analyses, with 14 randomized to the exercise condition and 15 to stretching. Overall, 59% of participants (n=17) reported taking psychiatric medications at baseline (13 on antidepressants, 3 on benzodiazepines, and 2 on stimulants); the other 41% were not taking any psychiatric medications.

Assessments

Participants completed a maximal exercise test using a Balke protocol consisting of 2-min stages in which speed and grade were increased over time. BDNF collection occurred immediately prior to test completion (resting serum BDNF) and immediately following test completion (changes in BDNF following acute exercise). After blood sample collection, the red top test tube was allowed to clot for 25±5 minutes at room temperature before being centrifuged at 3000 RPM for 15 minutes. The resulting serum was pipetted into 5 microtubules and stored in a −80 degree freezer. Results were batch processed at the Albert Einstein School of Medicine using Quantikine ELISA assay kits for total serum BDNF from R&D Systems. All serum BDNF results are in units of ng/ml. The Quantikine ELISA assay has specificity to assess mature BDNF with marginal reactivity to pro-BDNF (Polacchini et al., 2015).

Clinician and self-report depression ratings were made using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery and Asberg, 1979) and the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996), respectively. Exercise was assessed via the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (PAR; Blair et al., 1985), an interviewer-administered, timeline follow-back measure of minutes of vigorous and moderate intensity exercise and stretching. Metabolic equivalents (METs) were calculated for a combined variable of vigorous- and moderate-intensity exercise.

Assessments were completed at baseline, Week 4, Week 8, and Week 16 (1-month follow-up).

Intervention

The interventions are described in greater detail in the primary paper (Szuhany and Otto, 2019). In short, participants were randomized to either a brief behavioral activation (BA) treatment (9 sessions over 12 weeks) plus an adjunctive exercise or stretching control intervention. Stretching was designed to control for attention to bodily movement, but utilized movement at a lower intensity level hypothesized to not affect depression symptoms or BDNF levels. Exercise and stretching interventions included motivational strategies to enhance initiating and maintaining exercise/stretching regimens and planning at-home exercise/stretching with a goal of completing 150 minutes of exercise/stretching per week.

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted using mixed-effects linear regression models with likelihood-based estimation methods where follow-up assessments were entered as repeated dependent variables. For the analysis of acute changes in BDNF, treatment groups were combined to replicate meta-analytic comparisons (Szuhany et al., 2015). For subsequent models, treatment group, time, and their interaction were included as independent variables. Cross-time correlations were freely estimated using an unstructured variance-covariance matrix. Models were analyzed with both resting BDNF levels and change in BDNF levels from pre- to post-exercise as dependent variables. All analyses used SPSS Version 24.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline demographics are described in Table 1. Average resting BDNF levels at baseline were 28690 (±6870) ng/ml and average change score from pre- to post-exercise was 5265 (±10993) ng/ml. There was no significant difference between intervention conditions in total METs of exercise (t(29)=0.22, p=0.83, d=0.08) as reported in the primary paper (Szuhany and Otto, 2019), with both groups demonstrating significant increases in METs of exercise across treatment. Table 2 includes clinical, exercise, and BDNF measures by time point.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the randomized sample.

| BA + EX (n = 14) | BA + STR (n = 15) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 31.0 (13.0) | 37.2 (13.9) | .23 |

| Gender (%, n) | .18 | ||

| Female | 64% (9) | 87% (13) | |

| Male | 36% (5) | 13% (2) | |

| Race (%, n) | .05 | ||

| Caucasian | 50% (7) | 73% (11) | |

| African American | 0% (0) | 7% (1) | |

| Asian | 21% (3) | 20% (3) | |

| Other | 29% (4) | 0% (0) | |

| Ethnicity (%, n) | .96 | ||

| Hispanic | 7% (1) | 7% (1) | |

| Non-hispanic | 93% (13) | 93% (14) | |

| Principal Diagnosis (%, n) | .90 | ||

| MDD | 64% (9) | 67% (10) | |

| PDD | 36% (5) | 33% (5) | |

| Co-principal Diagnosis (%, n) | .54 | ||

| GAD | 14% (2) | 20% (3) | |

| Social anxiety | 14% (2) | 7% (1) |

Note. p values derived from χ2 tests for race and t-tests for all other comparisons. BA=behavioral activation, EX=exercise, STR=stretching, MDD=major depressive disorder, PDD=persistent depressive disorder, GAD= generalized anxiety disorder. .

Table 2.

Clinical, exercise, and BDNF measures at each assessment point.

| BA + EX (n =14) | BA + STR (n = 15) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 16 | Baseline | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 16 | |

| n=14 | n=12 | n=10 | n=8 | n=15 | n=12 | n=12 | n=11 | |

| METs (M, SD) | 265.1 (381.4) | 690.3 | 946.2 | 739.5 | 456.0 | 492.3 | 889.5 | 578.2 |

| (583.1) | (471.5) | (476.5) | (445.7) | (639.7) | (474.7) | (511.0) | ||

| MADRS (M, SD) | 23.9 (7.6) | 19.0 (8.2) | 20.8 (9.1) | 12.0 (7.7) | 26.5 (8.2) | 19.1 (9.0) | 20.3 (10.3) | 15.6 (9.9) |

| BDI-II (M, SD) | 24.9 (9.7) | 21.5 (10.1) | 21.1 (12.5) | 9.8 (9.5) | 27.5 (10.2) | 19.4 (10.8) | 18.4 (10.2) | 13.1 (10.1) |

| Resting BDNF | 27289.9 | 28222 | 29229.7 | 25996.9 | 29998.3 | 29664.4 | 27350.6 | 26601.1 |

| (M, SD) | (6779.1) | (5436.6) | (6880.6) | (3807.4) | (6924.0) | (10946.2) | (10479.5) | (9237.3) |

| BDNF Change | 7540.4 | 11261.1 | 6610.1 | 7784.7 | 2802.0 | 2279.3 | 6859.7 | 9778.3 |

| (M, SD) | (12636.6) | (13255.5) | (13642.6) | (15027.9) | (8761.7) | (12640.7) | (14989.7) | (15774.1) |

Note. BA = behavioral activation, EX = exercise, STR = stretching, MADRS=Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, BDI II=Beck Depression Inventory-II, METs=metabolic equivalents; METs are calculated for combined vigorous & moderate intensity activity; BDNF measured in ng/mL.

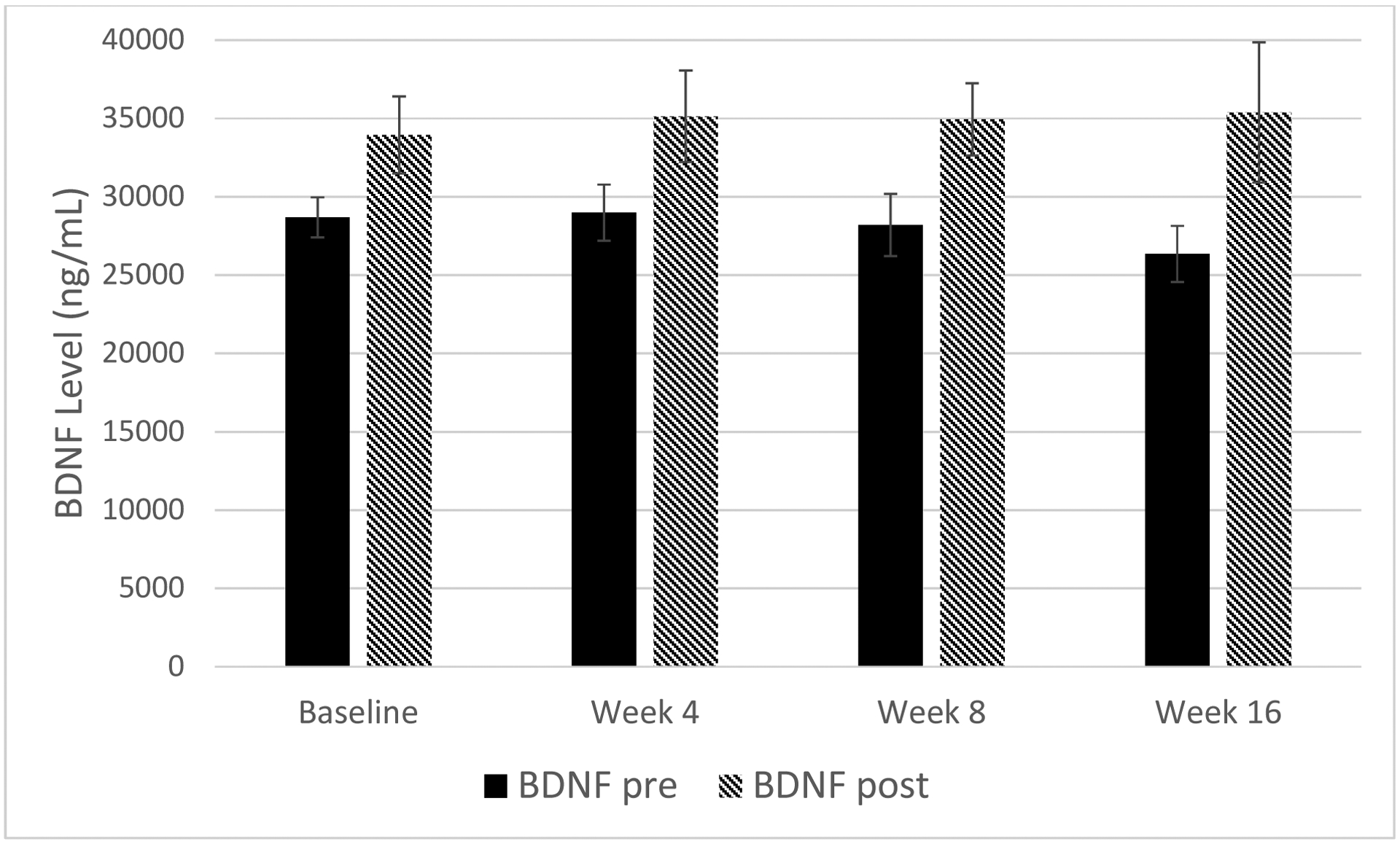

Effects on BDNF changes across an individual exercise session

In a one-sample t-test, BDNF change scores across assessment points during the study were shown to significantly increase (t(80)=4.61, p<0.001, d=0.83), as hypothesized. At each assessment point, BDNF levels increased significantly across an individual exercise session as evaluated by repeated measures t-test: baseline: t(24)=2.40, p=0.025, d=0.96; Week 4: t(20)=2.24, p=0.037, d=1.01; Week 8: t(19)=2.15, p=0.044, d=1.00; Week 16: t(14)=2.33, p=0.036, d=1.16. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean BDNF changes from pre- to post-exercise across all groups.

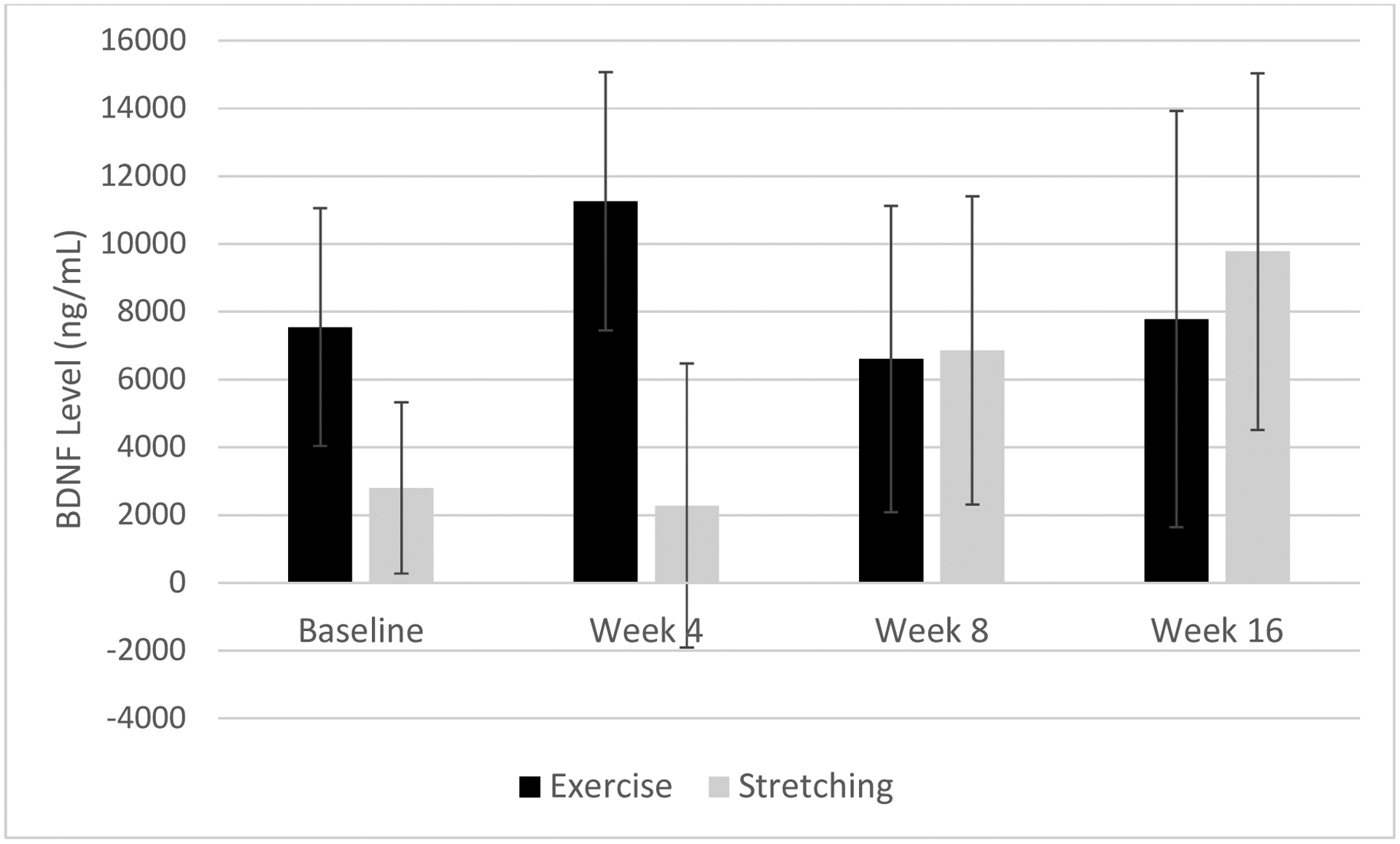

In a mixed effects model, main effects of time or condition (all p>0.46) and their interaction (p=0.74) were non-significant, consistent with the absence of differences in exercise between conditions as described in the primary paper (Szuhany and Otto, 2019). When METs of moderate and vigorous exercise were substituted for intervention condition, all effects remained non-significant (all p>0.13); however, the interaction between METs and time increased to a moderate effect size (F(3, 25)=2.06, p=0.13, d=0.53). See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Differences in pre- to post-exercise change in BDNF levels by augmentation condition (exercise or stretching) across the trial.

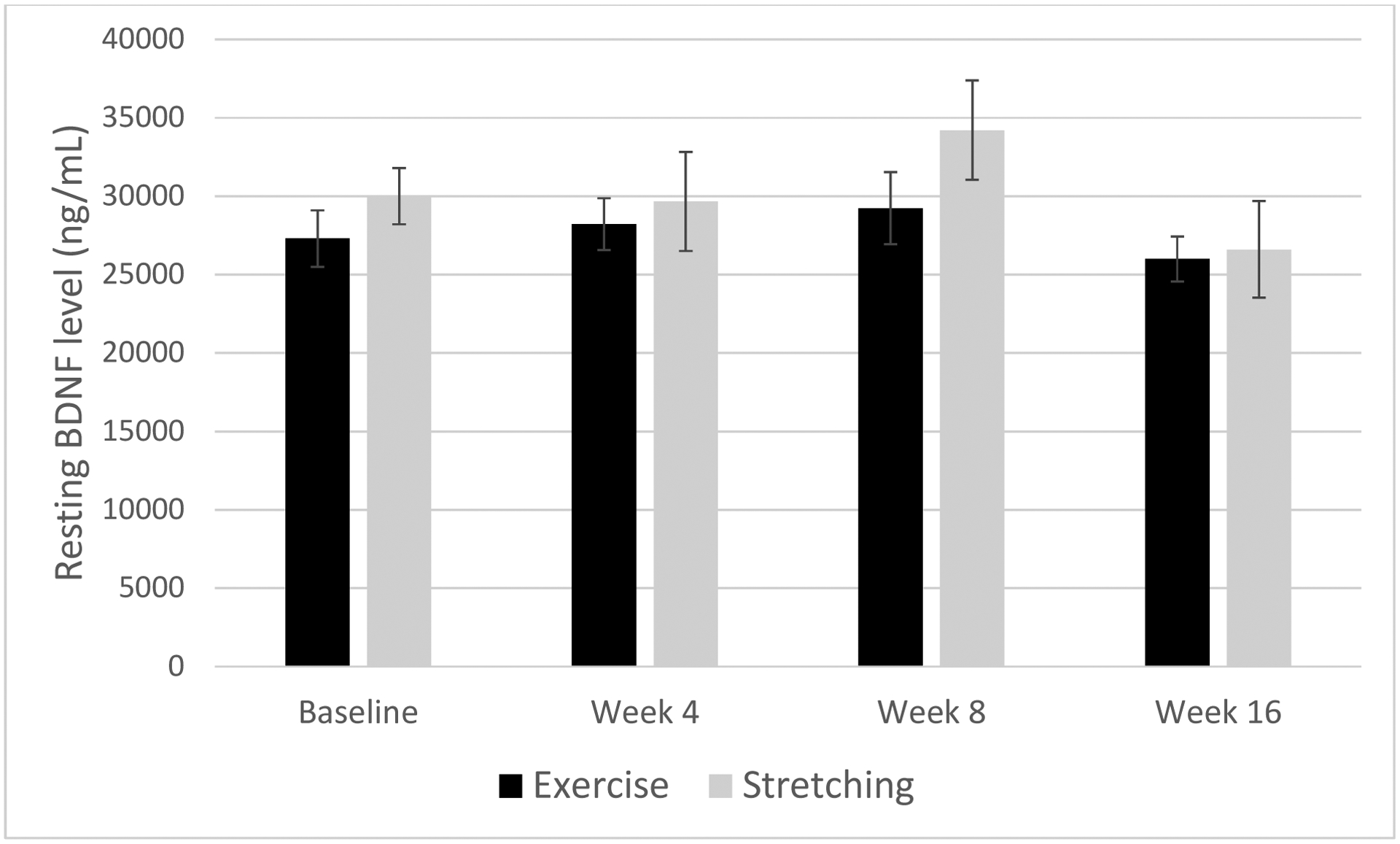

Effects on resting BDNF levels

A similar mixed effects model was conducted on resting BDNF levels. Results indicated no significant main effects of time or condition (all p>0.71) or interaction (p=0.75). When replacing condition with METs of moderate and vigorous exercise, all results were non-significant; however, the interaction between METs and time increased to a moderate effect size (F(3, 28)=1.64, p=0.20, d=0.49). See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Differences in resting BDNF by augmentation condition (exercise or stretching) across the trial.

Effects of BDNF on depression

The change in resting BDNF across the study period (baseline to endpoint) was not associated with depression changes as assessed by the MADRS (r=−0.19, p=0.49) or the BDI-II (r=0.25, p=0.34), and reflected effect sizes in the small to medium range. Likewise, the endpoint change in BDNF across exercise was not associated with depression changes on the MADRS (r=0.35, p=0.21) or BDI-II (r=−0.26, p=0.35), but reflected effect sizes in the small to medium range.

Discussion

Recent meta-analytic review (Szuhany et al., 2015) showed reliable moderate effects for increases in pre- to post-exercise BDNF levels following both acute and programs of exercise, but poorly represented individuals with psychiatric disorders. The current study, albeit underpowered, contributes effect size estimates of pre- to post-exercise BDNF changes across an exercise program. Consistent with the meta-analysis, depressed outpatients showed significant increases in BDNF across a single exercise session at each assessment point. Though non-significant, this study found a moderate effect (d=0.53) for the interaction between amount of exercise and time on BDNF changes from pre- to post-exercise. This effect size is consistent with that (Hedges’ g=0.58) found in the meta-analysis. We also found a non-significant, but moderate effect (d=0.49) for the interaction between amount of exercise and time on resting BDNF, an effect somewhat larger than that found in the Szuhany et al. (2015) meta-analysis (Hedges’ g=0.28), but similar to that of the Dinoff et al. (2018) meta-analysis (SMD=0.43). Hence, though the study was underpowered to reach significance for effects of this size, effects were generally consistent with those documented in quantitative reviews.

Previous research on the effect of acute exercise on BDNF has focused primarily on physically and mentally healthy individuals (Dinoff et al., 2017), though BDNF changes may be particularly important for depressed populations. This study found a significant change in the range of a large effect size (d=0.83) in BDNF at each of the four assessments from pre- to post-exercise. These results are consistent with meta-analytic results for diverse samples of participants (Hedges’ g=0.46, Szuhany et al., 2015), as well as two previous studies assessing BDNF change across a single exercise session in depressed patients (Gustafsson et al., 2009; Laske et al., 2010). Gustafsson and colleagues (2009) noted a larger change in BDNF in males (487 pg/ml to 1627 pg/ml) than females (367 pg/ml to 642 pg/ml).

In this study, BDNF changes were not associated with changes in depression, but reflected effect sizes in the small to medium range (r=0.25–0.35). Though this result was contrary to original hypotheses, at least three other studies from a recent meta-analysis (Dinoff et al., 2018) have found lack of correspondence between BDNF and depression changes (Kerling et al., 2017; Salehi et al., 2016; Toups et al., 2011), with only one finding an association (Gourgouvelis et al., 2018; R squared=0.50). It is unclear why some studies of depressed patients show an association between changes in BDNF and depression following an exercise program while others do not. Conflicting results may be due to small sample sizes or may suggest that BDNF is not the most sophisticated biomarker for acute antidepressant effects. Future research may also consider collecting data on depression age of onset or number of depressive episodes, as evidence with plasma BDNF shows these could be important mediating factors of the association between BDNF and depression changes, particularly for certain BDNF genotypes (Colle et al., 2017).

Several factors may have limited this study’s ability to produce results corresponding to previous literature. First, sample size was limited both by the pilot nature of the study and inability to obtain blood samples from some participants. Limited sample size may have interfered with the ability to find significant interactions of exercise and time on BDNF as well as BDNF associations with depression. Second, pre- and post-exercise BDNF levels were collected following a maximal exercise test. Individuals self-identify when to end this test when they feel they have reached their “maximum” capacity, thus varying length of test and possibly contributing to variable BDNF effects. Additionally, the exercise test was not administered post-intervention (Week 12); therefore, BDNF was not collected at this assessment point. Third, and perhaps most importantly, participants had two potential sources of benefit to depression symptoms: BA and exercise. Thus, the mechanism of improvement may have been diffused. Primary results indicated that BA appeared to be the stronger source of antidepressant benefit as there were no differential effects between adjunctive conditions (Szuhany and Otto, 2019).

The limitations of this study reveal methodological considerations important for future study planning. First, this includes standardizing the exercise test and recruiting a larger study sample. Given the small to moderate effect of the association between BDNF and depression changes, a sample of at least 85 participants would provide adequate power (r=0.30). We also recommend recruiting comparable samples of men and women to assess for moderation effects as past studies have indicated that BDNF responds differently in the sexes (Dinoff et al., 2017; Szuhany et al., 2015).

Of particular note for future research pertains to the assay for BDNF. BDNF is first synthesized as a pre-proneurotrophin (pro-BDNF) of 32KDa, which then cleaves into mature BDNF (14 KDa) or a truncated form of 28 KDa (Foltran and Diaz, 2016; Hempstead, 2015). Recent comparisons across the literature have noted discrepancies across BDNF studies, which may be due to the assays measuring BDNF (Polacchini et al., 2015). For example, the Quantikine assay used for this study has specificity to mature BDNF; whereas other assays measure both mature and pro-BDNF. Future studies should be careful to note the assay used and the type of BDNF measured.

In sum, this study provides additional data suggesting that BDNF response to acute exercise documented for healthy participants (Dinoff et al., 2017; Szuhany et al., 2015) extends to depressed outpatients. However, the effect sizes indicate that studies of approximately 85 participants may be needed to obtain significant associations between BDNF response and depression outcome when exercise is not the exclusive treatment method.

Highlights.

BDNF increases after acute exercise in a sedentary, depressed population

BDNF changes across acute exercise did not intensify during an exercise program

Resting BDNF levels did not change across an exercise program

BDNF changes were not associated with changes in depression symptoms

Future studies may require larger sample sizes given small effect sizes

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of M. Alexandra Kredlow and Josephine Lee for serving as study therapists; Bonnie Brown for drawing blood samples; Elijah Patten, Leslie Unger, Stephen Lo, Emily Carl, Melanie Watkins, and Abraham Eastman for serving as independent evaluators; and Gabrielle Figueroa, Sarah Oppenheimer, Ani Keshishian, Daniel Reichling, and Benjamin Woodward for help with data entry. BDNF processing was completed by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine with aid from grants: ICTR Einstein-Montefiore CTSA (UL1TR001073) and Diabetes Research Center (DK020541).

Role of the funding source

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health [F31 MH100773]. The funding source did not have any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest

In addition to Federal grant support, Dr. Otto receives royalties from multiple publishers (including royalties for books on exercise for mood) and receives speaker support from Big Health. Dr. Szuhany declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK, 1996. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX, 78204–72498. [Google Scholar]

- Blair SN, Haskell WL, Ho P, Paffenbarger RS Jr., Vranizan KM, Farquhar JW, Wood PD, 1985. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. American journal of epidemiology 122(5), 794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchio-Chiavetto L, Bagnardi V, Zanardini R, Molteni R, Nielsen MG, Placentino A, Giovannini C, Rillosi L, Ventriglia M, Riva MA, Gennarelli M, 2010. Serum and plasma BDNF levels in major depression: a replication study and meta-analyses. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 11(6), 763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunoni AR, Lopes M, Fregni F, 2008. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 11(8), 1169–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli F, Berry A, Chiarotti F, Alleva E, 2004. Intrahippocampal administration of BDNF in adult rats affects short-term behavioral plasticity in the Morris water maze and performance in the elevated plus-maze. Hippocampus 14(7), 802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colle R, Trabado S, David DJ, Brailly-Tabard S, Hardy P, Falissard B, Feve B, Becquemont L, Verstuyft C, Corruble E, 2017. Plasma BDNF Level in Major Depression: Biomarker of the Val66Met BDNF Polymorphism and of the Clinical Course in Met Carrier Patients. Neuropsychobiology 75(1), 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinoff A, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Gallagher D, Lanctot KL, 2018. The effect of exercise on resting concentrations of peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of psychiatric research 105, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinoff A, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Lanctot KL, 2017. The effect of acute exercise on blood concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in healthy adults: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Neuroscience. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Miller DL, Roecklein KA, 2012. The aging hippocampus: interactions between exercise, depression, and BDNF. The Neuroscientist 18(1), 82–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltran RB, Diaz SL, 2016. BDNF isoforms: a round trip ticket between neurogenesis and serotonin? Journal of neurochemistry 138(2), 204–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourgouvelis J, Yielder P, Clarke ST, Behbahani H, Murphy BA, 2018. Exercise Leads to Better Clinical Outcomes in Those Receiving Medication Plus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Major Depressive Disorder. Frontiers in psychiatry 9, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson G, Lira CM, Johansson J, Wisen A, Wohlfart B, Ekman R, Westrin A, 2009. The acute response of plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a result of exercise in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry research 169(3), 244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempstead BL, 2015. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: Three Ligands, Many Actions. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association 126, 9–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerling A, Kuck M, Tegtbur U, Grams L, Weber-Spickschen S, Hanke A, Stubbs B, Kahl KG, 2017. Exercise increases serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of affective disorders 215, 152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laske C, Banschbach S, Stransky E, Bosch S, Straten G, Machann J, Fritsche A, Hipp A, Niess A, Eschweiler GW, 2010. Exercise-induced normalization of decreased BDNF serum concentration in elderly women with remitted major depression. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 13(5), 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Kim H, Park SH, Kim YK, 2007. Decreased plasma BDNF level in depressive patients. Journal of affective disorders 101(1–3), 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorris T, Hale BJ, 2012. Differential effects of differing intensities of acute exercise on speed and accuracy of cognition: a meta-analytical investigation. Brain and cognition 80(3), 338–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M, 1979. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry 134, 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacchini A, Metelli G, Francavilla R, Baj G, Florean M, Mascaretti LG, Tongiorgi EJ, 2015. A method for reproducible measurements of serum BDNF: comparison of the performance of six commercial assays. Scientific Reports 5, 17989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roig M, Nordbrandt S, Geertsen SS, Nielsen JB, 2013. The effects of cardiovascular exercise on human memory: a review with meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 37(8), 1645–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo-Neustadt AA, Chen MJ, 2005. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and antidepressant activity. Current pharmaceutical design 11(12), 1495–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi I, Hosseini SM, Haghighi M, Jahangard L, Bajoghli H, Gerber M, Puhse U, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Brand S, 2016. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and aerobic exercise training (AET) increased plasma BDNF and ameliorated depressive symptoms in patients suffering from major depressive disorder. Journal of psychiatric research 76, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S, Duman R, Sanacora G, 2008. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and antidepressant medications: meta-analyses and implications. Biological psychiatry 64(6), 527–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Hoffman BM, Cooper H, Strauman TA, Welsh-Bohmer K, Browndyke JN, Sherwood A, 2010. Aerobic exercise and neurocognitive performance: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosomatic medicine 72(3), 239–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW, 2015. A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Journal of psychiatric research 60, 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szuhany KL, Otto MW, 2019. Efficacy evaluation of exercise as an augmentation strategy to brief behavioral activation treatment for depression: a randomized pilot trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toups MS, Greer TL, Kurian BT, Grannemann BD, Carmody TJ, Huebinger R, Rethorst C, Trivedi MH, 2011. Effects of serum Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor on exercise augmentation treatment of depression. Journal of psychiatric research 45(10), 1301–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Zhong J, Zou B, Fang L, Chen J, Deng X, Zhang L, Zhao X, Qu Z, Lei Y, Lei T, 2017. Meta-analyses of comparative efficacy of antidepressant medications on peripheral BDNF concentration in patients with depression. PloS one 12(2), e0172270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]