Abstract

Replacement of wild insect populations with genetically modified individuals unable to transmit disease provides a self-perpetuating method of disease prevention, but requires a gene drive mechanism to spread these traits to high frequency [1–3]. Drive mechanisms requiring that transgenes exceed a threshold frequency in order to spread are attractive because they bring about local, but not global replacement, and transgenes can be eliminated through dilution of the population with wild-type individuals [4–6]. These features are likely to be important in many social and regulatory contexts [7–10]. Here we describe the first creation of a synthetic threshold-dependent gene drive system, designated maternal-effect lethal underdominance (UDMEL), in which two maternally expressed toxins, located on separate chromosomes, are each linked with a zygotic antidote able to rescue maternal-effect lethality of the other toxin. We demonstrate threshold-dependent replacement in single- and two-locus configurations in Drosophila. Models suggest that transgene spread can often be limited to local environments. They also show that in a population in which single-locus UDMEL has been carried out, repeated release of wild-type males can result in population suppression, a novel method of genetic population manipulation.

Keywords: Gene drive, selfish genetic element, vector control, Medea, Mosquito, malaria, dengue

Results and Discussion

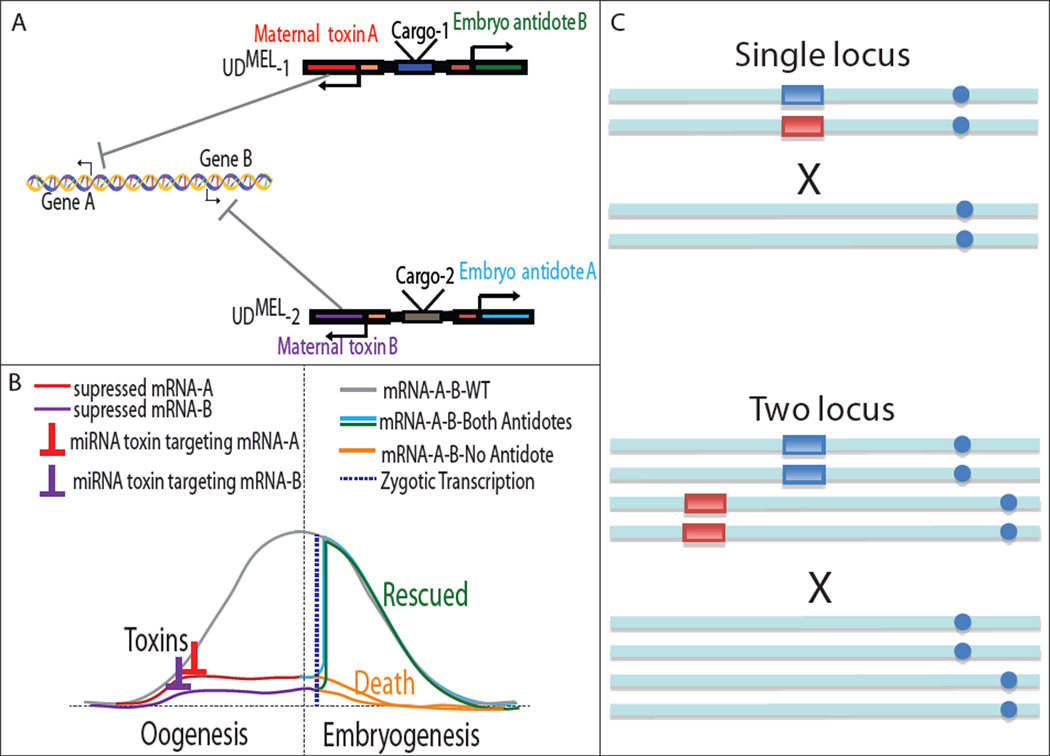

Threshold-dependent, chromosomal gene drive can occur when transgene-bearing chromosomes experience frequency-dependent changes in fitness with respect to non-transgene-bearing homologs such that the former have lower fitness at low frequency, and higher fitness at high frequency. These systems behave as a bistable switch, with the transgene-bearing chromosomes spreading to genotype fixation (the transgene is present in all individuals), and in some cases allele fixation (transgenes are present on all versions of the chromosome in the population), when present above a threshold frequency, while being lost from the population if their frequency falls below this threshold [4–6, 11, 12]. [4, 5, 11–15], Most threshold-dependent gene drive mechanisms have not been implemented; for those that have, such as translocations, large fitness costs and the practical difficulty in tightly linking genes of interest to the translocation breakpoint through inclusion within an inversion kept the system from further development [16, 17]. The threshold-dependent gene drive system described here, known as maternal-effect lethal underdominance (UDMEL), bears some similarity to an earlier proposed form of purely zygotic engineered underdominance [13]. The UDMEL system utilizes two constructs, each consisting of a maternally expressed toxin and a zygotically expressed antidote. Each antidote is linked with a toxin whose activity it does not rescue (toxin A linked with antidote B and visa versa). As a result, the survival of embryos from mothers carrying one (UDMEL-1) or both (UDMEL-1 and UDMEL-2) kinds of UDMEL chromosomes requires that they inherit the other (UDMEL-2) or both kinds of UDMEL chromosomes, respectively, in order to achieve zygotic rescue (Figure 1A,B; Figure S1). The likelihood of this happening is frequency-dependent, and represents a form of underdominant (heterozygous disadvantage) behaviour. Finally, because the toxins are only active when present in adult females, UDMEL chromosomes can be passed from males to viable offspring at normal Mendelian ratios. Each construct, consisting of a toxin-antidote pair, can be located at the same position on homologous chromosomes (single-locus UDMEL) (Figure 1C). In this configuration viable transgenics are always trans-heterozygotes, with half the progeny dying in each generation, as with some naturally-occurring balanced lethal systems [18, 19] (Figure S1A). Alternatively, UDMEL constructs can be located on non-homologous chromosomes (two-locus UDMEL) Figure 1C), in which case many more genotypes are viable (Figure S1B).

Figure 1. Schematic of the UDMEL drive system and illustration of how UDMEL rewires developmental gene expression.

The UDMEL system is composed of two constructs. UDMEL-1 consists of maternal toxin A (red) and zygotic antidote B (green) and UDMEL-2 consists of maternal toxin B (purple) and zygotic antidote A (light blue) (A). In wildtype mothers, maternal transcripts from gene A and gene B (gray line) are required for normal embryonic development. The toxins, multimers of miRNAs, degrade one or both of these mRNAs (red line for UDMEL-1 toxin A targeting Gene A, and purple line for UDMEL-2 toxin B targeting Gene 2), to which they are complementary. Embryos lacking one or both mRNAs and/or their products (orange lines), depending on whether the mother is heterozygous or transheterozygous, respectively, for the miRNA multimers, die. Progeny inheriting the other construct, or both constructs, respectively, survive because they express miRNA-resistant versions of the mRNAs (blue and green) in the early zygote at levels sufficient to rescue embryonic development. Dashed line (dark blue) corresponds to the initiation of zygotic transcription(B). Single- and two-locus UDMEL configurations are illustrated, with the two different constructs being indicated by the blue and red boxes, and homologous and non-homologous chromosomes indicated by the positions of their centromeres (blue circles). Wildtype chromosomes lack boxes (C).

We used a simple difference equation framework to model the spread of single and two-locus UDMEL through a randomly mating population. To investigate the confinement properties of single and two-locus UDMEL we follow the framework of Marshall and Hay [6], assuming a metapopulation model consisting of two populations, each of which exchanges a fraction, μ, of its population with the other each generation (Figure 2A). This model assumes that population size is constant, being limited by the carrying capacity of the environment, not the number of viable offspring produced per mating pair, as is observed with a majority of agricultural pests and disease vectors [20, 21]. Transgenic insects are introduced into population A, while population B initially consists of wildtype individuals.

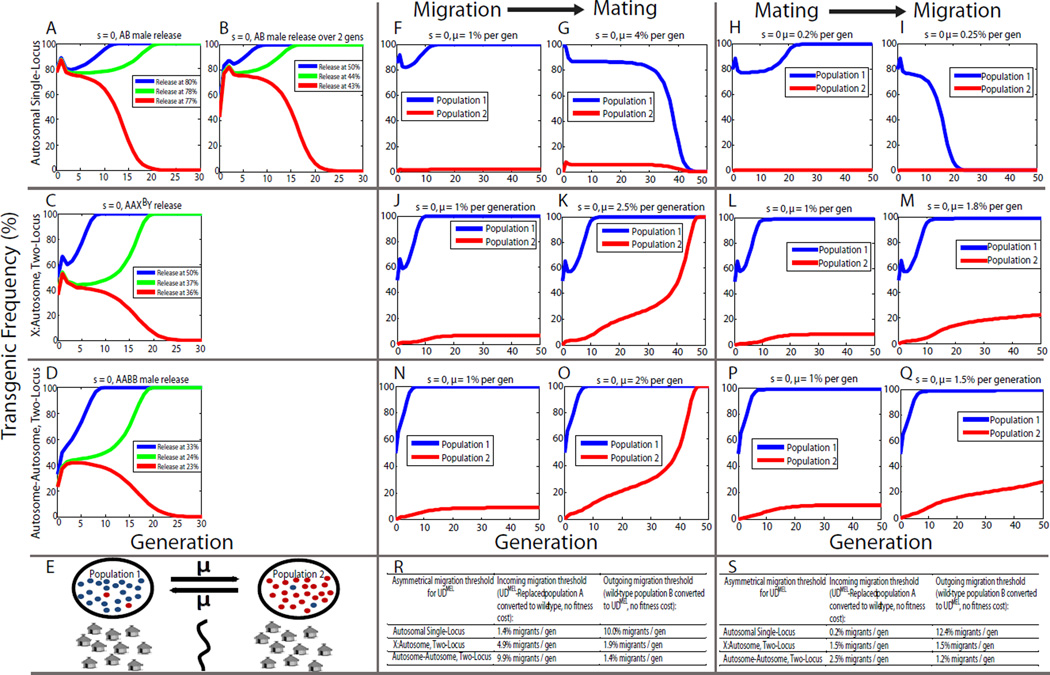

Figure 2. UDMEL single- and two-locus systems are predicted to show threshold-dependent gene drive and bring about local population replacement.

The threshold frequency above which a UDMEL drive system spreads into a population, and below which it is eliminated from the population, was calculated using a deterministic model and graphed. Release thresholds are calculated for two single locus scenarios: a single, all-male release of transheterozygotes (A) and two all male releases of transheterozygotes in the first and second generation (B), for elements with zero fitness cost (s). For X-autosome two-locus UDMEL (C) and autosome-autosome two-locus UDMEL (D) single releases of doubly homozygous males are illustrated. Introduction frequencies/transgene frequencies represent the fraction of individuals in the total population carrying at least one UDMEL construct. Two-way migration occurs between population 1, illustrated as a group village of houses, which has undergone population replacement, and population 2, which is separated from population 1 by a barrier (vertical line), and is initially all wildtype (E). Plots depict the dynamics of single- and two-locus UDMEL under two-population models in which migrants are exchanged between population 1 (blue line), which has been seeded with transgenics, and population 2 (red line), which initially consists only of wildtypes (F–Q). Migration occurs either prior to mating (F,G,J,K,N,O) or after mating (H,I,L,M,P,Q). For single-locus UDMEL, when migration occurs before mating and the migration rate is 1%, transgenics spread to high levels in population 1, and reach a frequency of 2.0% in population 2 (F); when the migration rate is 4%, transgenes are ultimately eliminated from both populations (G). When mating occurs before migration and the migration rate is 0.2%, transgenics spread to high frequency in population 1, and reach a frequency of ~1% in population 2 (H); a migration rate of 0.25% or higher results in loss of transgenes from both populations (I). For X-autosome two-locus UDMEL, when migration occurs before mating and the migration rate is 1%, transgenics spread to high frequency in population 1, and reach a frequency of 8% in population 2 (J); a migration rate of 1.8% or higher (2.5% is illustrated), results in spread to fixation in both populations (K). When mating occurs before migration and the migration rate is 1%, transgenics spread to high frequency in population 1 and reach a frequency of 8% in population 2 (L); a migration rate of 1.7% or higher (1.8% is illustrated) results in spread to fixation in both populations (M). For autosome-autosome, two-locus UDMEL, when migration occurs before mating and the migration rate is 1%, transgenics spread to high frequency in population 1, and reach a frequency of 8.8% in population 2 (N); a migration rate of 1.65% or higher (2% is illustrated), results in spread to fixation in both populations (O). When mating occurs before migration and the migration rate is 1%, transgenics spread to high frequency in population 1 and reach a frequency of 11% in population 2 (P); a migration rate of 1.4% or higher (1.5% is illustrated) results in spread to fixation in both populations (Q).

In the absence of other fitness costs, the single-locus system has a release threshold for trans-heterozygous males equivalent to 78% of the total (transgenic and +/+) population (6.5:1 transgenic males: wild males and females) (Figure 2B). This threshold decreases to a much more reasonable 44% (0.78:1) if releases are spread over two generations (figure 2C). In contrast, the threshold for a single release of males carrying two copies of an autosomal element and one copy of an X-linked element, a form of two-locus UDMEL, is significantly lower, 37% (Figure 2D). A single release of males doubly homozygous for two locus autosomal UDMEL has an even lower threshold, 24% (Figure 2E). Elements with an additive fitness cost can still drive, though as expected they have somewhat increased introduction thresholds (illustrated in Figure S2A–D for a 10% cost). Interestingly, for all reasonable fitness costs (up to 50% in the two-locus systems, data not shown), when spread occurs, it results in fixation of the transgenic allele (illustrated in Figure S3A–D for a 10% fitness cost).

In a system such as UDMEL, in which progeny survival depends on parental and progeny genotypes, it matters whether mating occurs before (ma-mi) or after (mi-ma) migration because the genotype distributions within the two populations will often be quite different. Here we consider the two extreme cases, in which all mating occurs before or after migration, to illustrate the range of possible outcomes. In single locus UDMEL, when migration precedes mating, and occurs at a rate of 1% per generation (the migration rate of Anopheles gambiae between neighboring villages in Mali [22]), transgenes spread to near-fixation at the release site (the failure to fix reflecting back migration of wildtypes from population 2), and transgenics reach a frequency of 2.0% in neighbouring populations (Figure 2F). Higher migration rates, up to 3.9% per generation, also fail to show drive in neighbouring populations, with the frequency of transgenics peaking at 7.1% for a migration rate of 3.5% per generation. When the migration rate is 4% or higher, transgenics are eliminated from both populations (Figure 2G) because migration of wild-type individuals into the release population results in the frequency of transgenics falling below the threshold required for spread. When mating precedes migration, the dynamics are qualitatively similar (Figure 2H, I), but the threshold for loss from both populations decreases dramatically, to 0.25% (Figure 2I), with transgenics reaching a maximum frequency of 0.1% in population 2. In consequence, the single-locus system is highly confineable; and is only able to show drive in isolated populations.

In two-locus X-autosome UDMEL, when migration precedes mating, and occurs at a rate of 1% per generation, transgenes spread to near-fixation at the release site, and transgenics reach a frequency of 8% in neighbouring populations (Figure 2J; also ~8% when ma-mi, Figure 2L). However, in contrast to the case of single-locus UDMEL, two-locus X-autosome UDMEL shows (in the absence of fitness costs) a clear migration threshold, above which the system becomes established in both populations (2% when mi-ma, Figure 2K; 1.7% when ma-mi, Figure 2M). Two-locus autosome-autosome UDMEL shows characteristics similar to those of two-locus Xautosome UDMEL, though higher frequencies of transgenics are found in neighboring populations (8.8% when mi-ma, Figure 2N; 11% when ma-mi, Figure 2P), and the migration threshold is lower (~1.65% when mi-ma, Figure 2O; 1.4% when ma-mi, Figure 2Q). Thus, while versions of two-locus UDMEL can be confined to isolated populations with low migration rates, the thresholds for spread are relatively low, and a more-detailed demographic analysis will be necessary to predict actual thresholds for spread in specific ecological settings.

Since migration may often be asymmetrical, either into or out of a replaced population, we also examined two limit cases: the incoming wildtype migration rate needed to convert a replaced population back to wildtype, and the outgoing transgenic migration rate needed to bring about replacement of a neighboring wildtype population (mi-ma, Figure 2 R; ma-mi, Figure 2S). Replacement with single-locus UDMEL is disrupted by low rates of wildtype migration into a replaced population, while high levels of migration from a single-locus UDMEL-replaced population are required for successful invasion of a neighboring wildtype population. In contrast, both versions of two-locus UDMEL shows the opposite behavior, with higher levels of wildtype migration being required to disrupt a UDMEL replaced population, and lower levels of UDMEL migration being sufficient to bring about replacement of a neighboring population.

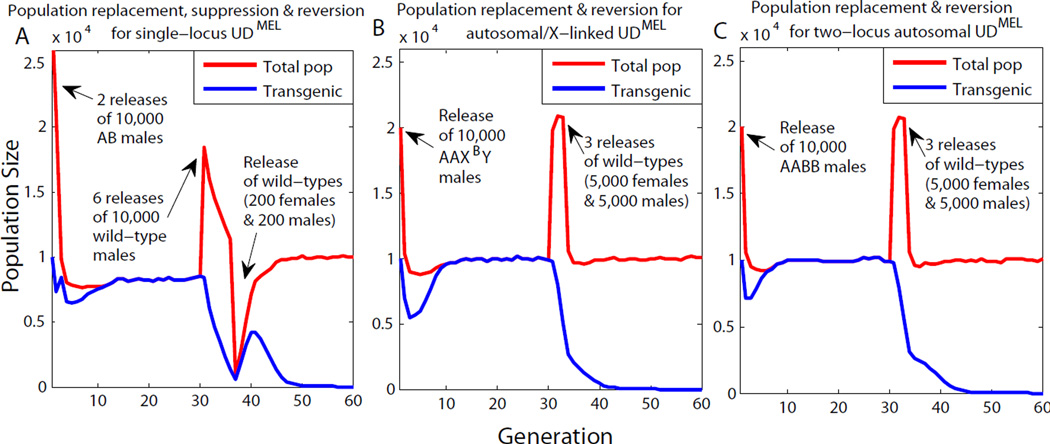

Finally, we note that single-locus and two-locus UDMEL provide realistic opportunities for transgene removal from the population (transgene recall), and/or population suppression. Thus, single-locus UDMEL, as well as several versions of single locus zygotic underdominance [4, 5, 13] (data not shown), have the property that when replacement has gone to allele fixation, repeated introductions of wild-type males can bring about suppression of the replaced population. This occurs because matings between UDMEL females and wildtype males produce only progeny with the wrong antidote, which are therefore inviable. This results in a population suppression effect similar to that seen in sterile male release programs [20]. If suppression is then followed by reintroduction of wildtype males and females, the population recovers, but the transgenes are lost because their frequency is now below that required for drive (Figure 3A). Population suppression cannot be carried out through a similar mechanism for X-autsome and autosome-autosome versions of two-locus UDMEL. However, three consecutive releases of wildtype males and females, totalling ~3X the wild population, are sufficient to drive the frequency of the UDMEL chromosomes below the threshold for spread, resulting in transgene elimination and reversion to a wildtype population (Figure 3B,C).

Figure 3. Introduction of wildtype individuals into UDMEL-replaced populations can result in population suppression, and/or loss of transgenes from the population.

Two releases of 10,000 males transheterozygous for single-locus UDMEL constructs with no fitness cost into a wildtype population of 10,000 results in UDMEL transgene fixation at ~ generation 12 (blue line). Six releases of 10,000 wildtype males into this population during generations 31–36 results in a population crash. Subsequent release of 200 wildtype males and females into the wild at generation 37 results in recovery of the total population to its wildtype, pre-transgenic numbers within 12 generations (red line). This is associated with loss of the UDMEL chromosomes, which have fallen below their threshold frequency for spread (A). One release of 10,000 AAXB Y males (B), or AABB males (C), into a wildtype population of 10,000, results in population replacement. Releases of 5,000 males and 5,000 females into the replaced population during generations 31 and 33 results in loss of transgenes from the population, but does not lead to population suppression.

Each toxin in the UDMEL system consists of a maternal-germline-specific promoter driving the expression of a multimer of synthetic miRNAs designed to silence expression of one or the other of three different genes: discontinuous actin hexagons (dah, CG6157), required for cellular blastoderm formation [23], O-fucosyltransferase 1 (o-fut1, also known as neurotic, CG12366), required for Notch signalling [24, 25], or myd88 (CG2078), required for Toll-dependent embryonic dorso-ventral pattern formation [26, 27]. Each of these genes is expressed maternally, with the product being essential for normal early embryonic development but not oogenesis. Zygotic rescue is achieved using versions of these transcripts, recoded so as to be invisible to the synthetic maternally-expressed miRNAs, and expressed under the control of a transient, early zygote-specific promoter.

One version of UDMEL utilizes silencing and rescue of dah and -myd88 (chromosomes bearing constructs UDMEL-dahT-myd88Aor UDMEL-myd88T-dahA) and is implemented in a single locus format on chromosome three. The second utilizes silencing and rescue of dah and o-fut1 (chromosomes bearing constructs UDMEL-dahT-o-fut1AorUDMEL-o-fut1T-dahA) and is implemented in a two-locus format on chromosomes two and three.

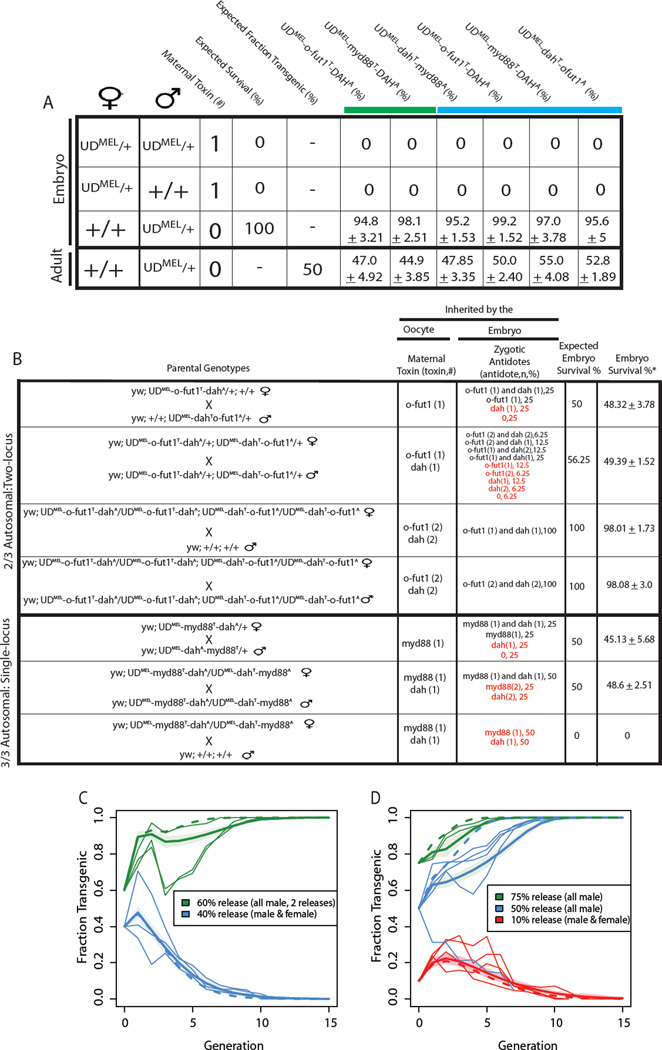

Matings between males heterozygous for each of the four UDMEL constructs (UDMEL /+) and homozygous +/+ females resulted in high levels of embryo viability and ~50% of the adult progeny carried the UDMEL construct, as expected for an element with Mendelian segregation and high fitness throughout the fly lifecycle (Figure 4A). In contrast, when UDMEL /+ females were mated with +/+ males, or with UDMEL /+ males heterozygous for the same construct, all progeny died as unhatched embryos or (very rarely) as early first instar larvae (Figure 4A). This indicates that a single maternal copy of each UDMEL construct is sufficient to bring about complete maternal-effect killing of progeny in the absence of the appropriate antidote. Trans-heterozygotes for the single- and two-locus UDMEL systems were generated through crosses between UDMEL /+ individuals heterozygous for the two different constructs. Approximately 50% of all embryos from these crosses hatched, and all adult progeny were transgenic, again indicating that one copy of the toxin is sufficient to kill, and that one copy of the appropriate antidote is sufficient for rescue (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Synthetic UDMEL chromosomes show maternal-effect lethal and zygotic rescue, underdominant behavior, and drive population replacement.

Crosses between parents of specific genotypes, either widltype or heterozygotes for the same UDMEL construct (indicated in the two leftmost columns) were carried out, and progeny survival to crawling first instar larvae quantified (rightmost 6 columns). The + indicates wildtype. The chromosome each UDMEL construct is inserted on is indicated by colour of the horizontal line (second chromosome, green; third chromosome, blue) (A). Crosses between parents of different genotypes (indicated to the left) were carried out. The maternal copy number of BicC-driven miRNAs targeting myd88, dah, or o-fut1 (toxin, n), and the zygote copy number of the bnk-driven, miRNA-resistant versions of myd88, dah, or o-fut1 (antidote, n) are indicated, as are the predicted and observed rates of embryo survival. The genotypes of embryos expected to survive are indicated in black, and those of embryos expected to die in red (B). *(embryo survival data were normalized to those of wild-type (w1118), which was 93.80± 3.19. Plots depict frequency of transgenics over generations in populations of +/+ (wildtypes) into which single-locus UDMEL transheterozygous (C) or two-locus UDMEL double homozygotes (D) were introduced. The % release indicates the fraction of the total population, post release, consisting of UDMEL individuals. All populations were followed for 15 generations, or until transgenic individuals were lost from the population. Thin lines represent experimental data. The thick line and surrounding shading represent a best-fit analysis of the data. The dashed line represents the predicted behavior of elements carrying no fitness cost.

For single locus UDMEL, surviving adults from a cross between UDMEL /+ individuals carrying different UDMEL chromosomes should be trans-heterozygous for the two UDMEL constructs. Consistent with this, crosses between transgenic female progeny of such a cross and +/+ resulted in no viable progeny. Importantly, however, crosses between putative trans-heterozygotes (in which females express two distinct toxins) resulted in ~50% progeny survival.

For two-locus UDMEL, crosses between trans-heterozygotes for both constructs resulted in ~50% embryo survival, close to the expected frequency, indicating that both antidotes are sufficient to rescue lethality due to expression of both toxins in mothers. This point is reinforced by the observation that in a cross between females doubly homozygous for both UDMEL constructs and +/+ males, in which mothers express two copies of both toxins and all progeny inherit one copy of each antidote, embryo survival is close to 100%. Finally, crosses between doubly homozygous UDMEL males and females also resulted in high levels of embryo viability, indicating that inheritance of two copies of each antidote does not compromise embryo survival (Figure 4B).

We initiated population replacement (drive-in) and transgene recall (drive-out) experiments by combining single-locus trans-heterozygotes, and two-locus double homozygotes, with ‘wild-type’ (+/+) individuals in several different ways (Figure 4C,D). We released only transgene-bearing males for super-threshold drive-in experiments, since for many insect vectors it is only females that bite and transmit disease. For drive-out experiments we utilized populations consisting of transgene-bearing males and females because an established transgenic population in the field will consist of both sexes. For single-locus UDMEL, we released males twice, during the first two generations, each time at a frequency of 60% with respect to the total post release population (1.5:1 trans-heterozygous males: +/+ males and females; predicted release threshold of 44%). Population replacement occurred in each of three experiments such that within 11 generations all individuals in the population were transgenic (Figure 4C). For the drive out experiments, trans-heterozygous males and females were combined with +/+ males and females in a ratio of 2:3, equivalent to releasing 60% +/+ into the replaced transgenic population. Both males and females were released because wildtype females are needed in order for the population to produce non-transgenic progeny. In each of three replicates the transgenes were completely lost from the population by generation 11 (figure 4C).

For two-locus UDMEL we initiated two super-threshold release experiments: with transgenic males provided at a frequency of 75% (a 3:1 ratio of doubly homozygous UDMEL males: +/+ males and females, 2 replicates), or 50% (a 1:1 ratio, 5 replicates). Population replacement occurred in all cages but one, in which the frequency of transgenics decreased rapidly in the second generation, perhaps due to poor mating efficiency with +/+ females. For the four replicate drive-out experiments, double homozygous males and females were combined with +/+ at a ratio of 1:9 (a double homozygote release ratio of 10%). In each case the population was rendered transgene free within 15 generations (Figure 4D).

Conclusions

Here we describe the first fully synthetic, threshold-dependent gene drive mechanism, UDMEL, able to bring about local and reversible population replacement. Modelling predicts that both single-locus and two-locus UDMEL drive systems should spread to transgene fixation and be confineable to local populations when migration rates are low. Our gene drive experiments support these predictions, and demonstrate clear threshold-dependence, implying that population replacement with UDMEL is reversible. Transgene removal can be achieved by dilution with wildtype males and females, as illustrated by the experiments described in Figure 4. Modeling suggests that it can also be accomplished in single-locus UDMEL through a combined strategy in which wild males are released first, to drive down population numbers through killing of heterozygotes, followed by the release of small numbers of wildtype males and females to restore the wild population, if desired (Figure 3).

The components needed to generate the UDMEL system - maternally expressed genes whose products are required for embryogenesis but not oogenesis, maternal- and early-zygote-specific promoters, and miRNAs - are also needed to build synthetic Medea selfish genetic elements, which have been shown to drive population replacement in Drosophila [28] [29], and are predicted to function as an invasive gene drive mechanism [30]. Genes and promoters with the desired characteristics are likely to exist in all insects, but largely remain to be identified in pest species of interest. Our work suggests that, once in hand, these components could be used to create a range of gene drive systems that are more or less confinable, and reversible through dilution with wildtypes, with single-locus UDMEL > X-autosome two-locus UDMEL > autosome-autosome two-locus UDMEL > Medea. This diversity may prove useful in allowing, to some extent, drive characteristics to be tailored to specific social, regulatory, and physical environments in which population replacement is being considered.

Finally, as the intrinsic introduction thresholds for the above drive mechanisms increase, so does the selection for mutations that silence toxin expression and/or activity, which would allow the reappearance of wildtypes. An important challenge is to identify molecular strategies that can best forestall the eventual breakdown of these elements, and allow for cycles of replacement when failure occurs. Multimerization of toxin-encoding genes, and the toxin-encoding miRNAs expressed by each gene (which will prevent the inactivation of individual miRNA units, or polymorphisms at their target sites, from preventing killing) provides one strategy. In addition, since second-generation UDMEL elements can in principal be generated that utilize toxin-antidote combinations distinct from those of first generation elements, it may be possible to carry out multiple cycles of population suppression if first-generation elements fail. Nonetheless, even with these and other strategies in place, it is possible that the use of very high threshold drive mechanisms such as single-locus UDMEL, will be limited to populations that are relatively small, and/or for which replacement or suppression is only needed temporarily.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A threshold-dependent gene drive system, UDMEL, is created. Transgenes can be removed from a replaced population by dilution with wildtypes. Modelling identifies contexts in which UDMEL-dependent drive can be confined. Releasing wildtype males into a replaced population can lead to population suppression.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants to BAH from the NIH (DP10D003878) and the Weston Havens Foundation, and to JMM from the Medical Research Council, UK

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, and three figures.

References

- 1.Braig HR, Yan G. The spread of genetic constructs in natural insect populations. In: Letourneau DK, Burrows BE, editors. Genetically Engineered Organisms: Assessing Environmental and Human Health Effects. CRC Press; 2001. pp. 251–314. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinkins SP, Gould F. Gene drive systems for insect disease vectors. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:427–435. doi: 10.1038/nrg1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay BA, Chen CH, Ward CM, Huang H, Su JT, Guo M. Engineering the genomes of wild insect populations: challenges, and opportunities provided by synthetic Medea selfish genetic elements. J Insect Physiol. 2010;56:1402–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altrock PM, Traulsen A, Reed FA. Stability properties of underdominance in finite subdivided populations. PLoS computational biology. 2011;7:e1002260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altrock PM, Traulsen A, Reeves RG, Reed FA. Using underdominance to bi-stably transform local populations. J Theor Biol. 2010;267:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall JM, Hay BA. Confinement of gene drive systems to local populations: a comparative analysis. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2012;294:153–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knols BG, Bossin HC, Mukabana WR, Robinson AS. Transgenic mosquitoes and the fight against malaria: managing technology push in a turbulent GMO world. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:232–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall JM. The Cartagena Protocol and genetically modified mosquitoes. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:896–897. doi: 10.1038/nbt0910-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mumford JD. Science, regulation, and precedent for genetically modified insects. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall JM, Toure MB, Traore MM, Famenini S, Taylor CE. Perspectives of people in Mali toward genetically-modified mosquitoes for malaria control. Malar J. 2010;9:128. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis CF. Possible use of translocations to fix desirable genes in insect pest populations. Nature. 1968;218:368–369. doi: 10.1038/218368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall JM, Hay BA. General principles of single construct chromosomal gene drive. Evolution. 2012;66:2150–2166. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis S, Bax N, Grewe P. Engineered underdominance allows efficient and economical introgression of traits into pest populations. J Theor Biol. 2001;212:83–98. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall JM, Hay BA. Inverse Medea as a novel gene drive system for local population replacement: a theoretical analysis. J Hered. 2011;102:336–341. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esr019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall JM, Pittman GW, Buchman AB, Hay BA. Semele: a killer-male, rescue-female system for suppression and replacement of insect disease vector populations. Genetics. 2011;187:535–551. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.124479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson AS. Progress in the use of chromosomal translocations for the control of insect pests. Biol. Rev. 1976;51:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1976.tb01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asman SM, McDonald PT, Prout T. Field studies of genetic control systems for mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1981;26:289–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.26.010181.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holsinger KE, Ellstrand NC. The evolution and ecology of permanent translocation heterozygotes. The American Naturalist. 1984;124:48–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace H. The balanced lethal system of crested newts. Heredity. 1994;73:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyck VA, Hendrichs J, Robinson AS, editors. Sterile Insect Technique: Principles and Practice in Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dye C. Models for the population dynamics of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. J. Anim. Ecol. 1984;53:247–268. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor C, Toure YT, Carnahan J, Norris DE, Dolo G, Traore SF, Edillo FE, Lanzaro GC. Gene flow among populations of the malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae, in Mali, West Africa. Genetics. 2001;157:743–750. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.2.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang CX, Lee MP, Chen AD, Brown SD, Hsieh T. Isolation and characterization of a Drosophila gene essential for early embryonic development and formation of cortical cleavage furrows. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:923–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasamura T, Sasaki N, Miyashita F, Nakao S, Ishikawa HO, Ito M, Kitagawa M, Harigaya K, Spana E, Bilder D, et al. neurotic, a novel maternal neurogenic gene, encodes an O-fucosyltransferase that is essential for Notch-Delta interactions. Development. 2003;130:4785–4795. doi: 10.1242/dev.00679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okajima T, Irvine KD. Regulation of notch signaling by o-linked fucose. Cell. 2002;111:893–904. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charatsi I, Luschnig S, Bartoszewski S, Nusslein-Volhard C, Moussian B. Krapfen/dMyd88 is required for the establishment of dorsoventral pattern in the Drosophila embryo. Mech Dev. 2003;120:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kambris Z, Bilak H, D'Alessandro R, Belvin M, Imler JL, Capovilla M. DmMyD88 controls dorsoventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:64–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CH, Huang H, Ward CM, Su JT, Schaeffer LV, Guo M, Hay BA. A synthetic maternal-effect selfish genetic element drives population replacement in Drosophila. Science. 2007;316:597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1138595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akbari OS, Chen C-H, Marshall JM, Huang H, Antoshechkin I, Hay BA. Novel synthetic Medea selfish genetic elements drive population replacement in Drosophila, and a theoretical exploration of Medea-dependent population suppression. ACS Synthetic Biology. 2012 doi: 10.1021/sb300079h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward CM, Su JT, Huang Y, Lloyd AL, Gould F, Hay BA. Medea selfish genetic elements as tools for altering traits of wild populations: a theoretical analysis. Evolution. 2011;65:1149–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.