Abstract

Aims: To evaluate the prevalence and risk factors of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) from 2000-2020 in various parts of Nepal. Methods: PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Google Scholar were searched using the appropriate keywords. All Nepalese studies mentioning the prevalence of T2DM and/or details such as risk factors were included. Studies were screened using Covidence. Two reviewers independently selected studies based on the inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software v.3. Results: Total 15 studies met the inclusion criteria. The prevalence of T2DM, pre-diabetes, and impaired glucose tolerance in Nepal in the last two decades was 10% (CI, 7.1%- 13.9%), 19.4% (CI, 11.2%- 31.3%), and 11.0% (CI, 4.3%- 25.4%) respectively. The prevalence of T2DM in the year 2010-15 was 7.75% (CI, 3.67-15.61), and it increased to 11.24% between 2015-2020 (CI, 7.89-15.77). There were 2.19 times higher odds of having T2DM if the body mass index was ≥24.9 kg/m 2. Analysis showed normal waist circumference, normal blood pressure, and no history of T2DM in a family has 64.1%, 62.1%, and 67.3% lower odds of having T2DM, respectively. Conclusion: The prevalence of T2DM, pre-diabetes, and impaired glucose tolerance in Nepal was estimated to be 10%, 19.4%, and 11% respectively.

Keywords: Blood Pressure, Body Mass Index, Diabetes Mellitus Type 2, Nepal

Introduction

In 2019, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimated that 463 million adults worldwide had diabetes 1. The statistics showed that these individuals were in the age range of 20 to 79, have diabetes, and 79.4% were from low- and middle-income countries 1. Additionally, IDF estimates that the global prevalence of diabetes will be 578.4 million by 2030, with this rising to 700.2 million by 2045 among adults aged between 20 to 79 years 1 In the region of Southeast Asia, the prevalence of diabetes was 8.8% in 2019, and this is projected to increase to 9.7% by 2030 2. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) still remains a major cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality, which leads to complications such as neuropathy, nephropathy, stroke, and coronary artery disease 3. In 2017, over 10, 000 individuals died due to T2DM or diabetes-related complications in Nepal, which is the 11th most common cause of disability in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (1226 DALYs per 10,000 population) 4. In 2020, the prevalence of T2DM in Nepal was 8.5% (95% CI 6.9–10.4%), which was higher than that of 8.4% (95% CI 6.2–10.5%) in 2014 5, 6. Similarly, in 2020 the prevalence of pre-diabetes was 9.2% (95% CI 6.6 – 12.6%) compared to 2014, which was 10.3% (95% CI 6.1–14.4%) 5, 6. In the advent of growing non-communicable diseases, a Multi-Sectoral Action Plan has been adopted by the government of Nepal to prevent and control non-communicable diseases including T2DM 7. However, there have not been many studies that evaluate the risk factors of T2DM in Nepal, which can be helpful for the prevention and control of this disease. We conducted this review to evaluate the prevalence and risk factors of pre-diabetes and T2DM in Nepal over the past 20 years, by pooling the studies done in various parts of the country.

Methods

Protocol registration

The systematic review is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020215247). It is documented as per the guidelines of the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) 8, 9.

Information sources and search strategy

Electronic databases such as PubMed, PubMed Central, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Embase were used to search relevant articles ( Extended data file 1 10). Published articles from 2000 to 2020 were searched with the use of the appropriate keywords such as “diabetes mellitus”, “high blood sugar”, “type 2 diabetes”, “prevalence”, “risk factor” and “Nepal” along with relevant Boolean operators.

Eligibility criteria

All published studies that took place in Nepal from 2000–2020 were included in this review. These studies comprised of cross-sectional studies, case series that reported on more than 50 patients, cohort study, randomized control trial (RCTs) that were based on prevalence of T2DM and/or its related issues such as risk factors, outcome, and outcome predictors.

Editorials, commentaries, viewpoint articles without adequate data on T2DM and its related issues were excluded. Furthermore, studies that took place before 1999, outside of Nepal, as well as those that were on Type 1 and gestational diabetes were excluded.

Study selection

The studies were selected with the use of Covidence 11. The title and abstract were screened based on the inclusion criteria independently by two authors (SL, SN). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus obtained from the third author (AM). Further full-text review (SN, AM) was done independently, and discrepancies (SL) were resolved.

Data collection process and data extraction

Three authors (SL, AM, and SN) were independently involved in the data extraction and adding that to a standardized form in Excel. The accuracy and completion of each other's work was verified by all the reviewers. The characteristics extracted for each selected study included, first author, year, study design, sample size, study location, prevalence rate, and risk factors of T2DM such as Body Mass Index (BMI), exercise (moderate to high level of exercise (≥ 30 minutes/days) is taken as adequate), waist circumference (≥85 cm in females, and ≥90 cm in males were defined as high), family history, fruit and vegetable serving per day, alcohol, smoking/tobacco, literacy, and increased blood pressure (BP) (≥140/90 mmHg is taken as hypertensive) (Please see Underlying data 12).

Data analysis

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (CMA) v.3 was used to analyze the extracted data.

Definition of the condition

T2DM was defined as a fasting blood glucose (FBG) of ≥ 126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/l) or a 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) blood glucose level of ≥ 200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l). Prediabetes was defined as FBG level between 100 (5.6 mmol/l) and 125 mg/dL (< 7 mmol/l) or a 2-h OGTT blood glucose level between 140 (7.8 mmol/l) and 199 mg/dl (11 mmol/l). Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) was defined as two-hour glucose levels of 140 to 199 mg per dL (7.8 to 11.0 mmol) on the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test 13.

Bias assessment

Bias assessment of the included studies was done by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool ( Table 1) 14.

Table 1. JBI checklist for bias assessment.

| Author/year | Was the

sample frame appropriate to address the target population? |

Were study

participants sampled in an appropriate way? |

Was the

sample size adequate? |

Were the

study subjects and the setting described in detail? |

Was the

data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? |

Were valid

methods used for the identification of the condition? |

Was the

condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? |

Was there

appropriate statistical analysis? |

Was the

response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharma B 16 et al. 2019 | yes | yes | No | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Gyawali B 17 et al. 2018 | yes | yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Sharma SK 18 et al. 2011 | yes | yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Sharma SK 19 et al. 2013 | yes | yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Chhetri MR 20 et al. 2009 | yes | yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Paudyal G 21 et al. 2008 | yes | yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Bhandari GP 22 et al. 2014 | yes | yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Karki P 23 et al. 2000 | yes | yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Paudel S 24 et al. 2020 | yes | yes | Yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Koirala S 25 et al. 2018 | yes | yes | yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Ranabhat K 26 et al. 2016 | no | yes | no | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Mehta KD 27 et al. 2011 | yes | yes | yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Shrestha UK 28 et al. 2006 | yes | yes | yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Dhimal M 29 et al. 2019 | yes | no | yes | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Kushwaha A 30 et al. 2020 | no | yes | no | Yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

Assessment of heterogeneity

The heterogeneity in the included studies was assessed based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews by the I 2 statistics (I 2>50%) 15. Thus, a random-effects model with the inverse variance heterogeneity model was performed. If I²>50% significant heterogeneity random effect model was preferred. If I²<50% then fixed effect model was preferred.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding studies that did not show any significant difference in the prevalence of T2DM.

Result

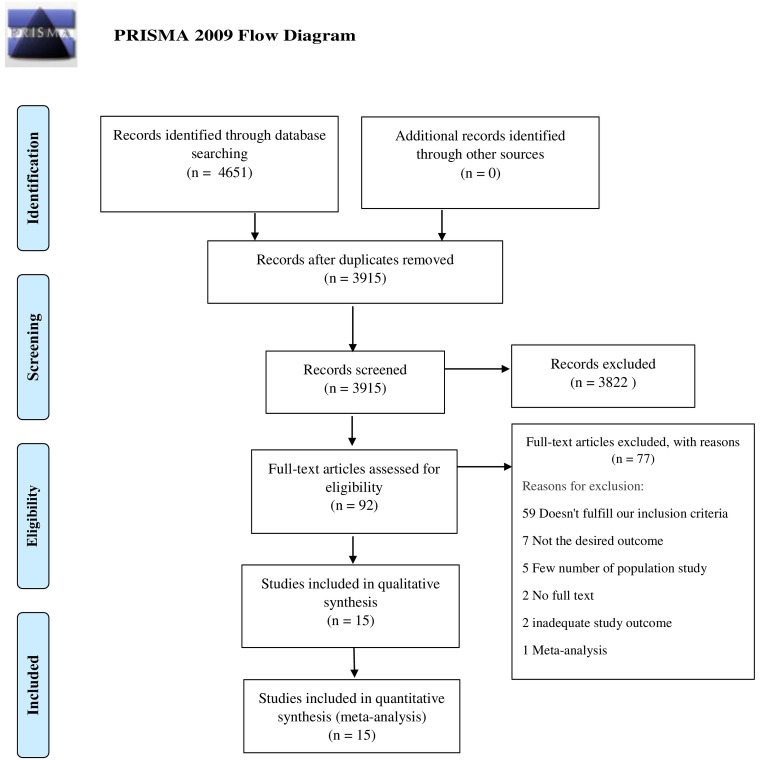

A total of 4651 studies were analyzed after thorough database search, of which 736 were identified as duplicates and removed. Title and abstracts of 3915 studies were screened and 3822 studies were excluded. The full-text eligibility of 92 studies was assessed and 77 studies were excluded for definite reasons. A total of 15 studies were included in the qualitative and quantitative analysis. The following information is depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram ( Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Qualitative summary

A qualitative summary of the individual study is presented in ( Table 2).

Table 2. Qualitative summary.

| Author/s | Study

Year |

Study Design | Sample Size | Study Area | Pre-diabetes | T2DM | IGT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhimal M 29 et al. 2019 | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | 12557 | 72 districts (all provinces) | 1067/12557 | ||

| Shrestha UK 28 et al. 2006 | 2006 | Cross-sectional study | 1012 | Seven wards of metropolitan and

sub-metropolitan of Nepal |

192/1012 | 107/1012 | |

| Kushwaha A 30 et al. 2020 | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | 114 | Community Hospital | 5/114 | ||

| Sharma B 16 et al. 2019 | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | 320 | Morang | 55/320 | 38/320 | 57/320 |

| Gyawali B 17 et al. 2018 | 2018 | Cross-sectional study | 2310 | Lekhnath municipality | 302/2310 | 271/2310 | |

| Sharma SK 18 et al. 2011 | 2011 | Cross-sectional study | 14425 | Eastern Nepal | 889/14008 | ||

| Sharma SK 19 et al. 2013 | 2013 | Cross-sectional study | 3218 | Dharan | 242/3218 | ||

| Chhetri MR 20 et al. 2009 | 2009 | Cross-sectional study | 1633 | Kathmandu valley | 422/1633 | ||

| Paudyal G 21 et al. 2008 | 2008 | Cross-sectional study | 1475 | Mulpani ,Gothar Kathmandu valley | 60/1475 | 34/1475 | |

| Bhandari G 22 et al. 2014 | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | 11901 | 31 selected hospital institutions

(28 non-speciality and 3 speciality) |

391/11901 | ||

| Karki P 23 et al. 2000 | 2000 | Cross-sectional Study | 1,840 | Outpatient clinic of BPKIHS | 116/1840 | ||

| Paudel S 24 et al. 2020 | 2020 | Secondary analysis of

the data |

1977 | Across Nepal | 179/1977 | ||

| Koirala S 25 et al. 2018 | 2018 | Cross-sectional study | 188(85M/103F) | Mustang district | 59/188 | 9/188 | |

| Ranabhat K 26 et al. 2016 | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | 154 (80M/74F) | Tribhuwan University Teaching

Hospital of Nepal |

66/154 | ||

| Mehta KD 27 et al. 2011 | 2011 | Cross-sectional study | 2006(1096M/910F) | Sunsari , Eastern Nepal | 422/2006 | 80/289 |

BPKIHS, B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences; F, female; IGT, Impaired Glucose Test; M, Male.

Quantitative synthesis

A total of 15 studies were included in the quantitative analysis.

Prevalence of T2DM

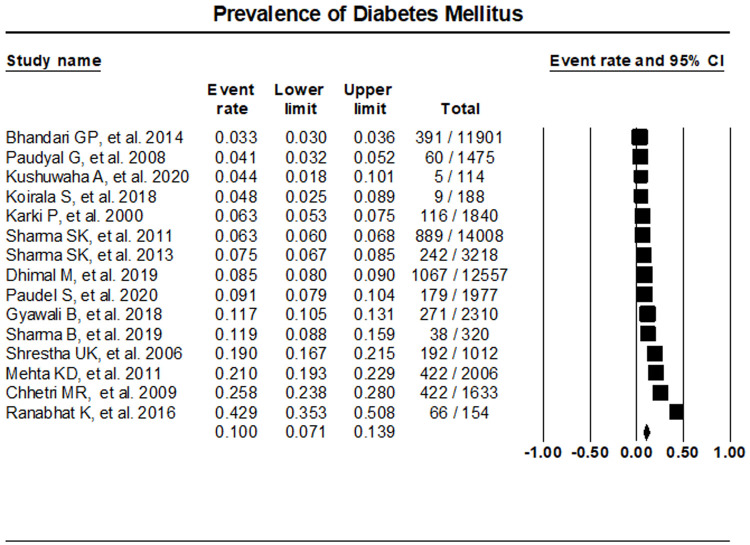

The random effects meta-analysis assessment of 15 studies indicated T2DM prevalence at 10% (95% CI, 7.1%- 13.9%) ( Figure 2). Sensitivity analysis was performed with the exclusion of individual studies which resulted in no significant differences in the prevalence of T2DM ( Extended data file 2, Figure 1 10)

Figure 2. Prevalence of T2DM in Nepal.

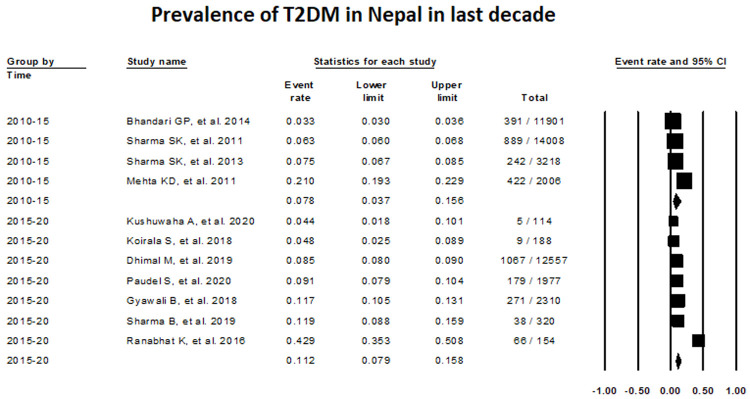

The assessment of T2DM prevalence between 2010–2015 with the use of random-effects meta-analysis was 7.75% (Proportion, 0.0775; 95% CI, 0.0367-0.1561; studies: 4; I 2:99.62), while this value increased to 11.24%, between 2015–2020 (Proportion, 0.1124; 95% CI, 0.0789-0.1577; I 2: 96.74) ( Figure 3).

Figure 3. Prevalence of T2DM in Nepal taking consideration of time frame from 2010–2020.

In relation to the study setting, the re-analysis of the data with the use of the random-effects model showed that 10.4% among surveyed adult population based on community-based studies had T2DM (Proportion, 0.1040; 95% CI, 0.0668-0.1596) ( Extended data file 2, Figure 2), while 9.23% among hospital/Directly observed, treatment short-course (DOTS) center-based studies have this disease (Proportion, 0.0923; 95% CI, 0.0509-0.1617) ( Extended data file 2, Figure 3 10).

Pre-diabetes was present in 19.4% (Proportion, 0.194; 95% CI, 11.2%- 31.3%) ( Extended data file 2, Figure 4) and IGT in 11.0% (Proportion, 0.110; 95% CI, 4.3%- 25.4%) ( Extended data file 2, Figure 5 10).

Risk factors of T2DM

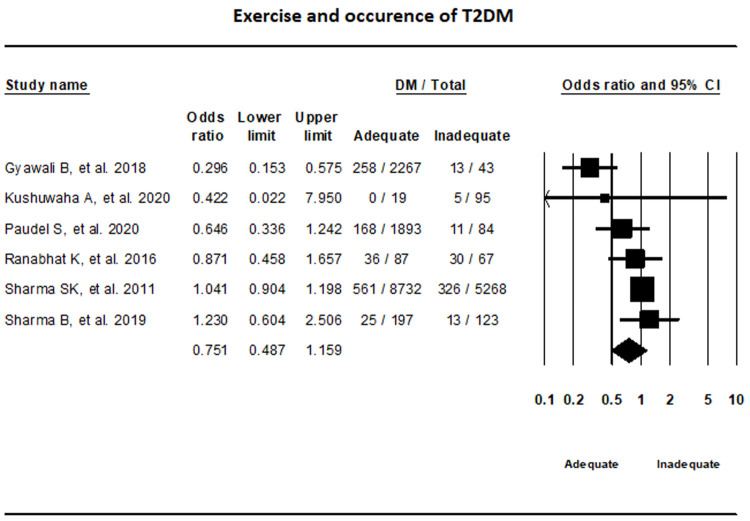

Exercise. Random-effects model that incorporated data from six studies on exercise showed that the difference in T2DM status between adequate and inadequate exercise groups were not statically significant (OR, 0.75, 95% CI, 0.49-1.16; I 2, 67.85%) ( Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot showing exercise status and T2DM in Nepal.

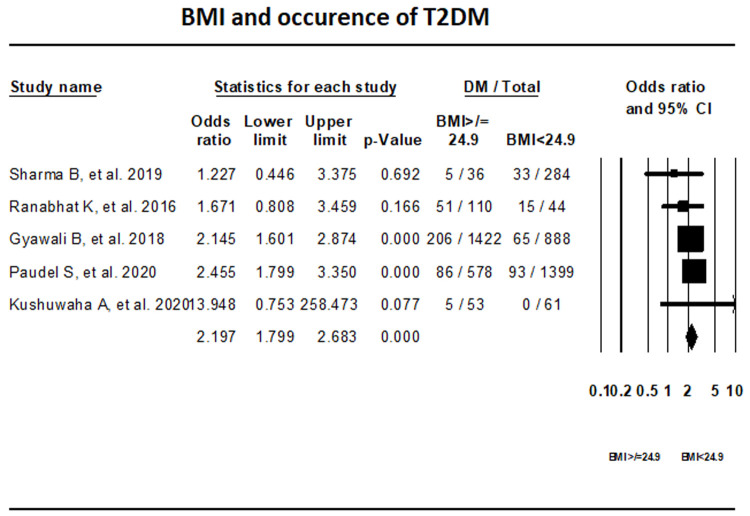

BMI. Fixed-effect meta-analysis of five studies that reported on the BMI indicated that with a BMI ≥24.9 kg/m 2 the odds of having T2DM is 2.19 times higher than with BMI <24.9 kg/m 2 (OR, 2.197; 95% CI, 1.799-2.683) ( Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot showing BMI category and T2DM in Nepal.

Waist circumference. Individuals with healthy waist circumference had 64.1% lower odds of having T2DM compared with those with high waist circumference (OR, 0.361; 95% CI, 0.284-0.460; I 2, 0%) ( Extended data file 2, Figure 4 10).

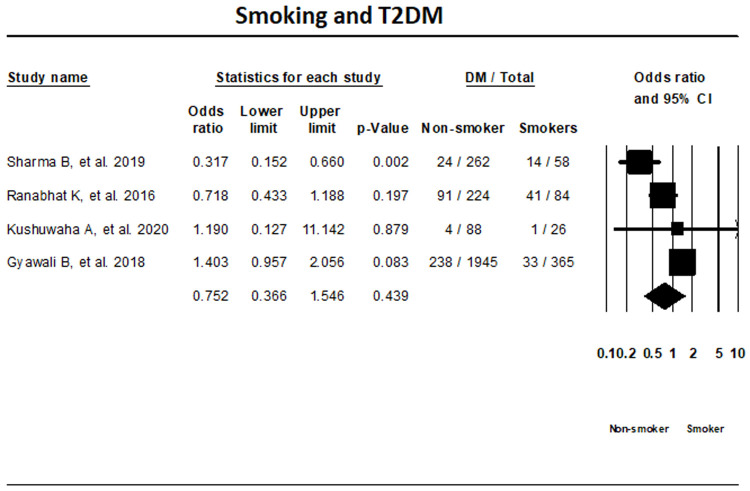

Smoking status. The random-effects meta-analysis of four T2DM studies based on smoking status indicated that the differences in T2DM status among smokers and non-smoker were not significant (OR, 0.752; 95% CI, 0.366-1.546; I 2; 87.2%) ( Figure 6).

Figure 6. Forest plot showing smoking status and T2DM in Nepal.

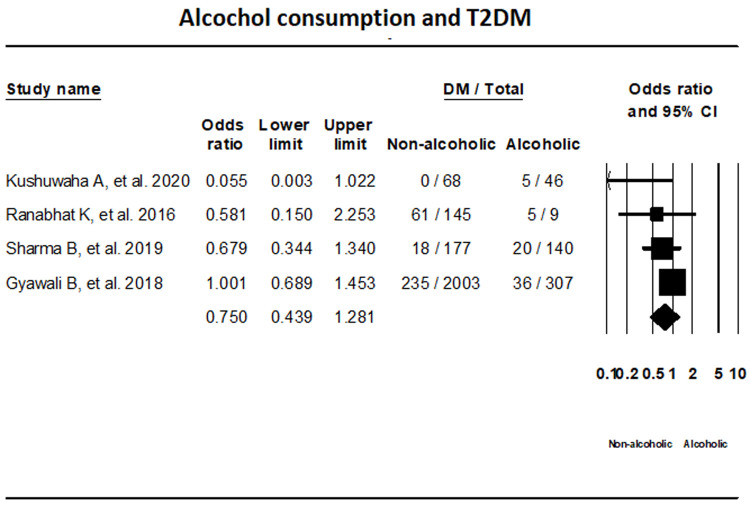

Alcohol consumption. T2DM status in relation with alcohol consumption was assessed by four studies with the use of random-effects model. The results showed that T2DM status among alcoholic and non-alcoholic groups were not statistically significant (OR, 0.750; 95% CI, 0.439-1.281 I 2; 37.72%) ( Figure 7).

Figure 7. Forest plot showing alcohol consumption status and T2DM in Nepal.

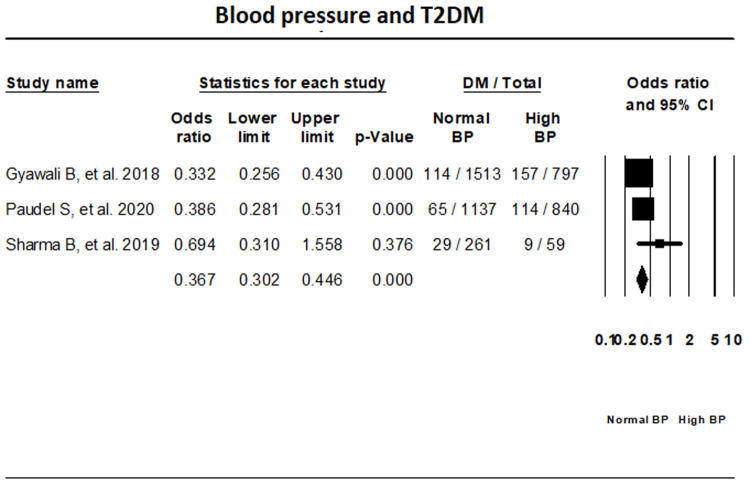

BP. Fixed-effect meta-analysis of three studies that have reported on T2DM status in relation with BP has indicated that the odds of individuals with normal BP having T2DM is 62.1% lower than those with high BP (OR, 0.379; 95% CI, 0.290-0.495) ( Figure 8).

Figure 8. Forest plot showing blood pressure status and T2DM in Nepal.

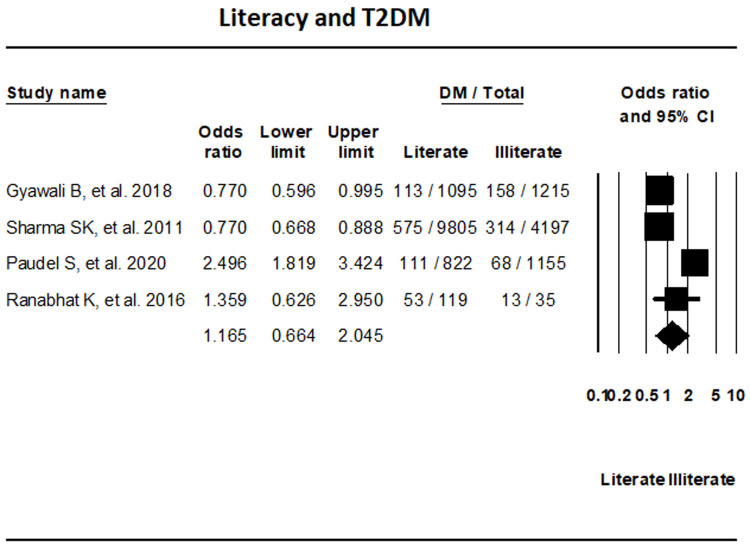

Literacy. The assessment of four studies that reported on T2DM based on literacy status did not show any significant differences in T2DM between literate and illiterate groups (OR, 1.165; 95% CI, 0.664-2.045; I 2, 93.61%) ( Figure 9).

Figure 9. Forest plot showing literacy status and T2DM in Nepal.

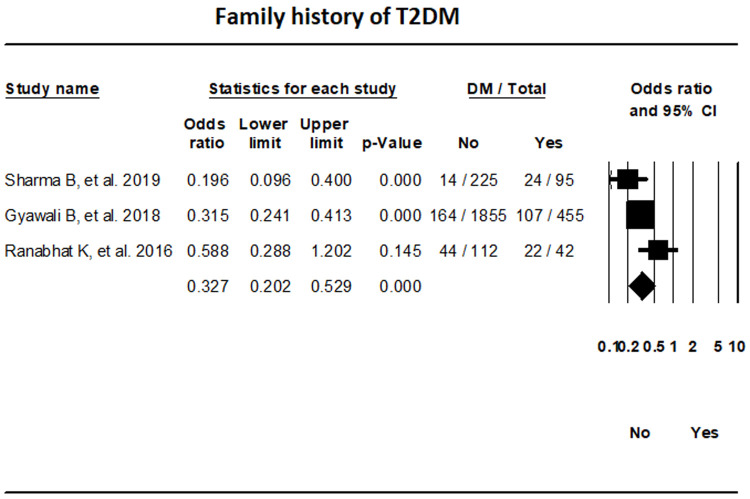

Family history. The random-effects meta-analysis of three studies indicated that the odds of T2DM in individuals without a family history of T2DM were 67.3% lower in comparison to those with a family history (OR, 0.327; 95% CI, 0.202-0.529; I 2, 56.62%) ( Figure 10).

Figure 10. Forest plot showing the family history of T2DM and Diabetes status in patients in Nepal.

Fruits and vegetables intake. The data assessment of the two studies that had reported on T2DM status in relation to fruits and vegetable intake did not reach a significant difference (OR, 0.933; 95% CI, 0.441-1.976; I 2, 78.72%). ( Extended data file 2, Figure 7 10).

Publication bias. Publication bias among the included studies were tested with the use of Egger’s test and was presented in a Funnel plot. The prevalence of T2DM in the Funnel plot showed an asymmetric distribution of studies, which suggested publication bias ( Extended data file 2, Figure 8 10).

Discussion

The prevalence of T2DM, pre-diabetes, and IGT in Nepal was found to be 10%, 19.4%, and 11% respectively. Our results show that in Nepal obesity is the highest risk factor for T2DM, while individuals with normal waist circumference and lack of family history of T2DM had lower risk of T2DM.

The estimated prevalence of T2DM was higher than that reported in WHO STEP wise approach to Surveillance (STEPS) survey in 2013 (3.6%), and previous meta-analyses (8.4% and 8.5%) 5, 6, 31. Similarly, the estimated prevalence of pre-diabetes in our study was almost double than what has been reported in other studies 5, 6. One explanation for this finding can be the rapid urbanization, and migration from rural to urban areas which has promoted a sedentary lifestyle among individuals, along with consumption of unhealthy foods 32. As per our study, high BMI was the main cause of T2DM in Nepal. In South Asia, lifestyle factors such as poor diet, and increased sedentary behaviors with limited physical activities have contributed to the rise of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents 33. Rapid development of the economic situation in developing countries like Nepal has resulted in a change of diet rich in cereal and vegetables to one with animal products and processed food with high fat and sugar content 34. In a study by Hills et al. the prevalence of overweight in Nepal was estimated to be 16.7%, with a higher prevalence in women (19.6%) compared to men (13.6%) 34. Obesity is closely linked with premature onset of T2DM and cardiovascular disease 35. A similar increasing trend of T2DM led by obesity is seen in Africa as well 36. It is important to target T2DM risk factors in order to take control of this disease in Nepal. Our finds highlight the importance of exercise and a healthy diet to prevent the increased morbidity among individuals with T2DM in this country. Shrestha et al. found that the T2DM awareness to be low, with nearly half of the population unaware of the fact that they had this disease 6. Increasing public awareness about non-communicable diseases like T2DM and hypertension, and the need to implement a healthy lifestyle is of paramount importance given that our results indicated that individuals with normal blood pressure had less chance of developing T2DM compared to those with hypertension. Increased intake of oily foods, reusing cooking oils which can cause increased conversion of unsaturated fats to trans fats, and low consumption of fruits and vegetables have been found throughout South Asia 37, 38. These unhealthy dietary habits lead to increased risks of non-communicable diseases like T2DM and hypertension. Thus, interventions are needed to better manage the overweight and obesity epidemic. This can be achieved through various measures such as opening public parks in the cities for exercise, educating the population about what a healthy lifestyle entails such as decreasing the intake of oily foods, increasing the intake of fruits and vegetable, as well as improving the quality of food. Our study has several strengths. Firstly, we performed comprehensive literature search to pool the results of fifteen studies over the last twenty years to evaluate the prevalence of T2DM in Nepal. In addition, no prior meta-analysis has evaluated the risk factors for T2DM, specifically IGT in Nepal, prior to our study. We also analyzed data based on a time frame, where significant increase in T2DM prevalence was observed in Nepal when comparing 2010–2015 with 2015–2020. Our study had some limitations. There was heterogeneity in the studies due to variation in the T2DM diagnostic criteria, different demographics of the population, etc. Most of the included studies were based on specific areas such as province 1 and 3, and not enough studies have been done on a national scale. Finally, risk factors for T2DM were not reported in all the studies that were included.

Conclusion

The prevalence of T2DM, pre-diabetes and IGT in Nepal was estimated to be 10%, 19.4% and 11% respectively. Obesity is the major risk factor of T2DM in Nepal and people with normal waist circumference, normal blood pressure and lack of family history of T2DM had lower odds of developing this disease.

Data availability statement

Underlying data

Figshare: Diabetes Mellitus in Nepal from 2000 to 2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14706648.v1 12

The project contains the following underlying data:

Dataset: Quantitative data, glycemic control, socio-economic status, BMI, exercise, T2DM prevalence, waist circumference, family history, fruit and vegetable serving per day, alcohol consumption, smoking, education, and BP)

Extended data

Figshare: Diabetes Mellitus in Nepal from 2000 to 2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14854065.v1 10

The project contains the following underlying data:

Data file 1: Electronic search details

Data file 2: Additional analysis

Data file 3: PRISMA checklist

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

Authors' contributions

DBS, PB, and YRS contributed to the concept and design, analysis, and interpretation of data. DBS, PB, AM, SL, SN, AA, and AP contributed to the literature search, data extraction, review, and initial manuscript drafting. YRS, SN, and AA interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final manuscript.

All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; peer review: 3 approved with reservations]

References

- 1.IDF Diabetes Atlas 9th edition.2019; [cited 2021 Mar 29]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, et al. : Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9 th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yau JWY, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. : Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):556–64. 10.2337/dc11-1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanal P, Nielsen MO: Is foetal programming by mismatched pre- And postnatal nutrition contributing to the prevalence of obesity in Nepal? Prev Nutr Food Sci.Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition;2019;24(3):235–44. 10.3746/pnf.2019.24.3.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyawali B, Sharma R, Neupane D, et al. : Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Nepal: a systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000 to 2014. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):29088. 10.3402/gha.v8.29088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shrestha N, Mishra SR, Ghimire S, et al. : Burden of Diabetes and Prediabetes in Nepal: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Ther.Adis;2020;11(9):1935–46. 10.1007/s13300-020-00884-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra SR, Kallestrup P, Neupane D: Country in Focus: confronting the challenge of NCDs in Nepal. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.Lancet Publishing Group;2016;4(12):979–80. 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30331-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. : Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budhathoki P, Shrestha D, Marahatta A, et al. : Diabetes Mellitus in Nepal, A Meta-Analysis of prevalence and risk factor studies.PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020215247. [cited 2021 May 19]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Sedhai YR, et al. : Extended data- Diabetes Mellitus in Nepal from 2000 to 2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis.2021; [cited 2021 Jun 27]. 10.6084/m9.figshare.14854065.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. [cited 2021 May 13]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Sedhai YR, et al. : Diabetes Mellitus in Nepal from 2000 to 2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis. figshare. 2021; [cited 2021 Jun 27]. 10.6084/m9.figshare.14706648.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care.American Diabetes Association;2009;32 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S62–7. 10.2337/dc09-S062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.critical-appraisal-tools - Critical Appraisal Tools.Joanna Briggs Institute. [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 15.9.5.2 Identifying and measuring heterogeneity. [cited 2020 Dec 18]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma B, Khanal VK, Jha N, et al. : Study of the magnitude of diabetes and its associated risk factors among the tuberculosis patients of Morang, Eastern Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1545. 10.1186/s12889-019-7891-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyawali B, Hansen MRH, Povlsen MB, et al. : Awareness, prevalence, treatment, and control of type 2 diabetes in a semi-urban area of Nepal: Findings from a cross-sectional study conducted as a part of COBIN-D trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206491. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma SK, Ghimire A, Radhakrishnan J, et al. : Prevalence of hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome in Nepal. Int J Hypertens. 2011;2011:821971. 10.4061/2011/821971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma SK, Dhakal S, Thapa L, et al. : Community-based screening for chronic kidney disease, hypertension and diabetes in dharan. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2013;52(189):205–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chhetri MR, Chapman RS: Prevalence and determinants of diabetes among the elderly population in the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2009;11(1):34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paudyal G, Shrestha MK, Meyer JJ, et al. : Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy following a community screening for diabetes. Nepal Med Coll J.Nepal Pediatric Ocular Diseases Study View project Reconstructing Nepali Population History View project Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy following a community screening for diabetes.2008;10(3):160–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhandari GP, Angdembe MR, Dhimal M, et al. : State of non-communicable diseases in Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):23. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karki P, Baral N, Lamsal M, et al. : Prevalence of non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in urban areas of eastern Nepal: a hospital based study. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31(1):163–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paudel S, Tran T, Owen AJ, et al. : The contribution of physical inactivity and socioeconomic factors to type 2 diabetes in Nepal: A structural equation modelling analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30(10):1758–67. 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koirala S, Nakano M, Arima H, et al. : Current health status and its risk factors of the Tsarang villagers living at high altitude in the Mustang district of Nepal. J Physiol Anthropol. 2018;37(1):20. 10.1186/s40101-018-0181-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranabhat K, Mishra SR, Dhimal M, et al. : Type 2 Diabetes and Its correlates: A Cross Sectional Study in a Tertiary Hospital of Nepal. J Community Health. 2017;42(2):228–34. 10.1007/s10900-016-0247-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta KD, Karki P, Lamsal M, et al. : Hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, hypertension and socioeconomic position in eastern Nepal. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011;42(1):197–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrestha UK, Singh DL, Bhattarai MD: The prevalence of hypertension and diabetes defined by fasting and 2-h plasma glucose criteria in urban Nepal. Diabet Med. 2006;23(10):1130–5. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01953.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhimal M, Karki KB, Sharma SK, et al. : Prevalence of Selected Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases in Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2019;17(3):394–401. 10.33314/jnhrc.v17i3.2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kushwaha A, Kadel AR: Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among people attending medical camp in a community hospital. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2020;58(225):314–7. 10.31729/jnma.4953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aryal KK, Mehata S, Neupane S, et al. : The burden and determinants of non communicable diseases risk factors in Nepal: Findings from a nationwide STEPS survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134834. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adhikari B, Mishra SR: Culture and epidemiology of diabetes in South Asia. J Glob Health. 2019;9(2):020301. 10.7189/jogh.09.020301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misra A, Khurana L: Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11 Suppl 1):S9–30. 10.1210/jc.2008-1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hills AP, Arena R, Khunti K, et al. : Epidemiology and determinants of type 2 diabetes in south Asia. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.Lancet Publishing Group;2018;6(12):966–78. 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30204-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta N, Goel K, Shah P, et al. : Childhood obesity in developing countries: Epidemiology, determinants, and prevention. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(1):48–70. 10.1210/er.2010-0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC): Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1377–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhardwaj S, Passi SJ, Misra A, et al. : Effect of heating/reheating of fats/oils, as used by Asian Indians, on trans fatty acid formation. Food Chem. 2016;212:663–70. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanungsukkasem U, Ng N, Van Minh H, et al. : Fruit and vegetable consumption in rural adults population in indepth hdss sites in asia. Glob Health Action. 2009;2(1):35–43. 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]