Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Inflammation is increasingly recognized as a target to reduce residual cardiovascular risk. Colchicine is an anti-inflammatory drug that was associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes. However, its effect on stroke reduction was not consistent across studies. Therefore, the aim of this study-level meta-analysis was to evaluate the influence of colchicine on stroke in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).

METHODS:

Electronic databases were searched through October 2020, to identify randomized controlled trials using colchicine in patients with CAD. The incidence of clinical endpoints such as stroke, death, myocardial infarction (MI), study-defined major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and atrial fibrillation (AF) was compared between colchicine and placebo groups.

RESULTS:

A total number of 11,594 (5,806 in the colchicine arm) patients from 4 eligible studies were included in the final analysis. Stroke incidence was lower in the colchicine arm compared to placebo (rate ratio [RR] 0.48 [95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29–0.78], P = 0.003) whereby no significant difference was observed in the incidence of AF (odds ratio [OR] 0.86 [95% CI, 0.69–1.06], P = 0.16). Furthermore, a significant effect of colchicine on MACE [RR 0.65 (95% CI, 0.51–0.83), P = 0.0006] and MI (RR 0.65 (95% CI, 0.54–0.95], P = 0.02) was detected, with no influence on all-cause mortality (RR 1.04 [95% CI, 0.61–1.78], P = 0.88).

CONCLUSIONS:

This meta-analysis confirms a significant influence of colchicine on stroke in CAD patients. Despite its neutral effect on AF occurrence, other mechanisms related to plaque stabilization are plausible. The concept seems to be supported by contemporaneous MI reduction and posits that anti-inflammatory properties of colchicine may translate into a reduction of stroke risk.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, colchicine, inflammation, stroke

Introduction

Despite the dynamic progress in controlling cardiovascular risk factors alongside the significant improvements in its treatment, stroke remains one of the leading causes of death and long-term disability worldwide.[1] A significant proportion of patients remains at high risk of cardiovascular events, including stroke, even when guideline-directed treatment targets are achieved with estimated annual risk of recurrent stroke of 2.5%–4%.[2,3,4] This underscores the importance of atherosclerotic residual risk, with inflammation representing one of the key drivers for future cardiovascular events.

Inflammation plays a pivotal role in the development of atherosclerosis and has been considered a fundamental target for potential therapies aimed at diminishing the risk of adverse cardiovascular events.[2] Recently, the canakinumab antiinflammatory thrombosis outcome study confirmed the “inflammation hypothesis” by demonstrating that anti-inflammatory treatment with canakinumab, a human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-1β, translated into a lower risk of cardiovascular events.[5] These promising results fuelled research on therapies altering inflammatory pathways with colchicine gaining ever-increasing interest as a medication reducing future cardiovascular events in a wide spectrum of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).[6,7,8,9] The agent has a wide range of anti-inflammatory activities by inhibiting neutrophil function and altering NALP3 inflammasome – a shared pathway with canakinumab.[10]

Large randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have reported stroke reduction in response to colchicine given on a background of guideline-directed treatment, although these results were not consistent among studies.[6,7,8,9] Importantly, these trials were not powered to detect differences in individual endpoints, including stroke. Therefore, first, we sought to conduct a study-level meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of colchicine on the incidence of stroke in a wide spectrum of CAD patients. Second, given that AF is the second-most common cause of stroke and that inflammation is considered to be one of the mechanisms of AF initiation and maintenance, we aimed to assess whether a potential reduction of stroke incidence is related to differences in new-onset/recurrent AF.

Methods

The meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) guidelines.[11] Online databases (MEDLINE and Web of Science) were searched from their inception till October 2020 using the following keywords: colchicine, stroke, CAD, acute coronary syndrome, randomized control trial, and inflammation. Full reports were retrieved after screening citations at title/abstract level and were included when considered relevant. Using prespecified inclusion criteria, two authors (MA and MK) made the initial assessment and any disagreement was resolved by consensus. The results were also cross-checked by reviewing systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the use of colchicine treatment.

Clinical trials were included if they met the following three inclusion criteria: (1) RCT of colchicine versus placebo; (2) recruited patients with CAD; and (3) major cardiovascular outcomes as the primary endpoint of the trial. Studies evaluating blood biomarkers, such as troponin or high-sensitivity CRP, or angiographic data like stent restenosis as their primary endpoints were excluded from the analysis. Similarly, studies investigating the role of colchicine in other inflammatory diseases, for example, pericarditis or gout, were also excluded. The primary endpoint was the incidence of ischemic stroke as defined in the included studies. Other clinical endpoints such as death, myocardial infarction (MI), atrial fibrillation (AF), and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (as defined by each study) were also included. Gastrointestinal (GI) side effects were also compared between colchicine and placebo groups as reported in each study.

After data extraction, pooled rate ratio (RR) (for stroke, MI, MACE, and all-cause mortality), odds ratio (OR) (for AF), and 95% confidence interval (CI) between colchicine and placebo were calculated using a random-effects model based on the inverse variance method. The presence of heterogeneity across the studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Q test and quantified using the Higgins I2 test. The statistical analysis was performed using the RevMan software version 5.3 and P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

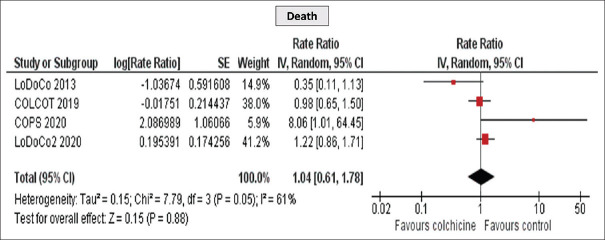

Thousand one hundred and four citations from the online databases were identified and matched the prespecified inclusion criteria. A flow diagram of the studies screen, assessed for eligibility, and included in the meta-analysis along with reasons for exclusions is shown in Figure 1. Ultimately, four RCT enrolling 11,594 patients (5,806 in the colchicine arm) were included. The clinical characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Colchicine dose was similar across the included studies (0.5 mg once daily), except for the Colchicine in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome (COPS) (0.5 mg twice daily for 1 month followed by 0.5 mg once daily for 11 months). Two RCTs included patients with stable CAD. Clinical characteristics of included studies are presented in [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow chart

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the included studies

| Included studies | Nidorf et al., 2013 LoDoCo trial | Tardif et al., 2019 COLCOT trial | Tong et al., 2020 COPS trial | Nidorf et al., 2020 LoDoCo2 trial | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 532 | 4745 | 795 | 5522 | ||||

| Study population | Patients with stable CAD | Patients with a recent MI (recruited within 30 days after MI) | Patients with ACS and angiographic evidence of CAD | Patients with chronic CAD (stable for at least 6 months before enrollment) | ||||

| Protocol | Colchicine/placebo=0.5 mg once daily | Colchicine/placebo=0.5 mg once daily | Colchicine/placebo=0.5 mg twice daily for first month, then 0.5 mg once daily for 11 months | Colchicine/placebo=0.5 mg once daily | ||||

| Primary endpoint | The composite incidence of ACS, OHCA, or noncardioembolic ischemic stroke | The composite of death from cardiovascular causes, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina leading to coronary revascularization | The composite of all-cause mortality, ACS, ischemia-driven (unplanned) urgent revascularization and non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke | The composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous (nonprocedural) MI, ischemic stroke, or ischemia-driven coronary revascularization | ||||

| Follow-up | Median of 36 months | Median of 22.6 months | Median of 371 days | Median of 28.6 months | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Treatment | Colchicine | Placebo | Colchicine | Placebo | Colchicine | Placebo | Colchicine | Placebo |

|

| ||||||||

| Mean age | 66±9.6 | 67±9.2 | 60.6±10.7 | 60.5±10.6 | 59.7±10.2 | 60.0±10.4 | 65.8±8.4 | 65.9±8.7 |

| Male | 251 (89) | 222 (89) | 1894 (80.05) | 1942 (81.6) | 322 (81) | 310 (78) | 2305 (83.5) | 2371 (86) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 92 (33) | 69 (28) | 462 (19.5) | 479 (20.9) | 75 (19) | 76 (19) | 632 (22.9) | 662 (24) |

| Smoking | 10 (4) | 14 (6) | 708 (29.9) | 708 (29.8)* | 128 (32) | 149 (37) | 318 (11.5) | 330 (12) |

| Previous MI or unstable angina | 64 (23) | 61 (24) | 370 (15.6) | 397 (16.7) | 59 (15) | 59 (15) | 2323 (84.1) | 2335 (84.6) |

| CABG | 62 (22) | 39 (16) | 69 (2.9) | 81 (3.4) | 15 (4) | 19 (5) | 319 (11.5) | 391 (14.2) |

| PCI | 169 (60) | 138 (55) | 392 (16.6) | 406 (17.1) | 51 (13) | 50 (13) | 2100 (75.0) | 2077 (75.3) |

| HTN | NR | NR | 1185 (50.1) | 1236 (52) | 201 (51) | 199 (50) | 1421 (51.4) | 1387 (50.3) |

| Stroke or TIA | NR | NR | 55 (2.3) | 67 (2.8) | 5 (1) | 11 (3) | NR | NR |

| High dose statin | 271 (96) | 235 (94) | 2339 (98.9) | 2357 (99.1) | 389 (98) | 397 (99) | 2594 (93.9) | 2594 (94) |

ACS: Acute coronary syndrome, CAD: Coronary artery disease, MI: Myocardial infarction, OHCA: Our-of-hospital cardiac arrest, NR: Not reported, TIA: Transient ischemic attack, PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention, HTN: Hypertension, CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting

There was no significant publication bias based on the symmetry of the reconstructed funnel plot of the standard error of the log RR against the RR.

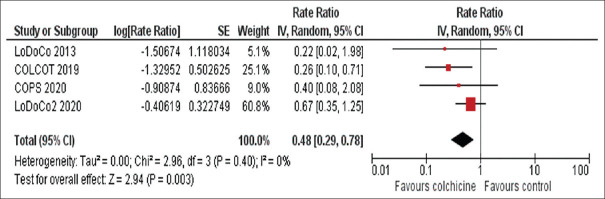

Colchicine was associated with a 52% risk reduction in the incidence of stroke as compared to placebo (RR 0.48 [95% CI, 0.29–0.78], P = 0.003) [Figure 2]. The effect of colchicine was consistent regardless of whether patients presented as stable angina (RR 0.61 [95% CI 0.33–1.12], P = 0.11) or as acute coronary syndrome (RR 0.30 [95% CI 0.13–0.69], P = 0.005) (P = 0.17 for interaction). An influence analysis showed that the reduction of stroke was consistent and was not driven by a single study, including the withdrawal of the COLCOT trial (RR0.58 [95% CI 0.33–1.03], P = 0.06).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of stroke events of included studies. Rate ratios and 95%. confidence intervals of colchicine versus placebo in patients with coronary artery disease

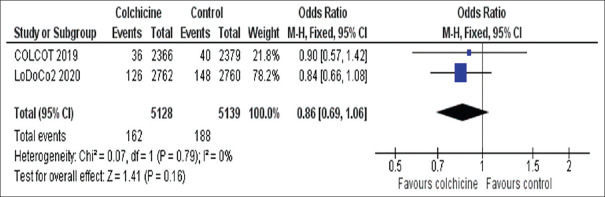

AF was assessed as an outcome in 2 of the included RCTs (COLCOT and LoDoCo2) and the present meta-analysis revealed a comparable incidence of AF in both groups (OR 0.86 [95% CI, 0.69–1.06], P = 0.16) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis from the two studies reporting atrial fibrillation events. Rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals of colchicine versus placebo in patients with coronary artery disease

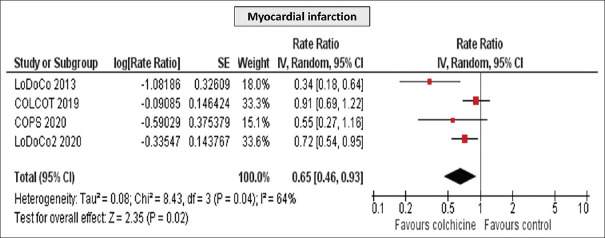

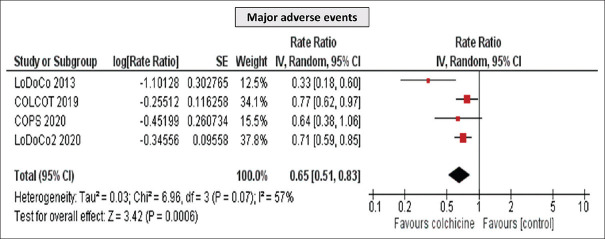

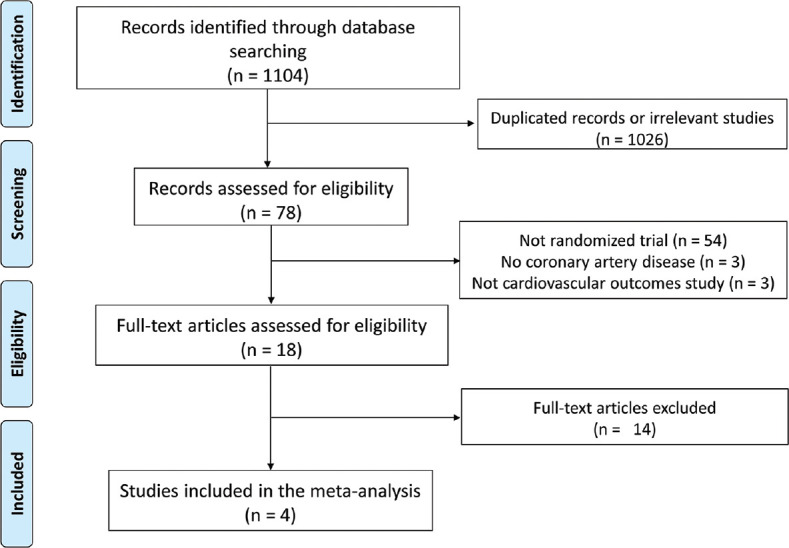

Furthermore, a significant reduction in MI (RR 0.65 [95% CI, 0.54–0.95], P = 0.02) and MACE (RR 0.65 [95% CI, 0.51–0.83], P = 0.0006) was detected [Figures 4 and 5], while no difference was observed in all-cause mortality (RR 1.04 [95% CI, 0.61–1.78], P = 0.88) [Figure 6]. Importantly, the incidence of GI side effects did not differ between the studied groups (RR 0.65 [95% CI, 0.51–0.83], P = 0.81).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of myocardial infarction of the included studies. Rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals of colchicine versus placebo in patients with coronary artery disease

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of major adverse cardiovascular event of the included studies. Rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals of colchicine versus placebo in patients with coronary artery disease

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of Death of the included studies. Rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals of colchicine versus placebo in patients with coronary artery disease

Discussion

The present meta-analysis revealed that colchicine is an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for preventing stroke in a high-risk population with established CAD. Colchicine was associated with a 52% relative risk reduction in the incidence of stroke compared to placebo. Previous meta-analyses reported on the benefits of colchicine for the prevention of stroke. However, they included observational studies that are subjective to bias and hinder their ability to assess causation, despite statistical adjustment for known confounders. Since RCTs are the gold standard in evaluating interventions, we performed the meta-analysis including exclusively RCTs which target CAD patients treated with colchicine. Apart from stroke risk reduction, a significant effect of colchicine on MACE and MI was detected, with no influence on all-cause mortality. Our findings confirm that addressing residual cardiovascular risk beyond optimal medical therapy is of vital significance and translates into improved clinical outcomes.[2,12]

Inflammation is central in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis which is the main underlying pathological cause of cardiovascular diseases such as CAD and stroke. Both clinical entities not only share a common atherothrombotic mechanism, risk factors and therapeutic strategies, but also a considerable cross-risk between these two conditions exists.[13,14,15,16] Therefore, there is a significant association between CAD and the risk of stroke which provides a rationale for conducting research on novel interventions by targeting inflammation to address this clinical issue.[17]

Previous experimental studies on animal models have demonstrated that the NLRP3 inflammasome has a significant role in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke and postischemic inflammation.[18] Furthermore, inhibiting upstream and downstream pathways of NLRP3 signaling might represent an important therapeutic target to reduce effects of ischemic stroke such as infarct size.[19,20,21] Moreover, it has been suggested that inhibition of NLRP3 might also prevent ischemic stroke.[22,23] Whether colchicine exerts its benefits on stroke reduction is yet to be determined, nonetheless, results from experimental studies are in line with the findings of the meta-analysis.

The potential role of colchicine in the prevention of stroke has been a matter of recent interest. LoDoCo trial was the first study showing a beneficial role of colchicine in the reduction of cardiovascular events, however, without influence on the incidence of stroke.[6] Results of the previous meta-analyses were also inconclusive and importantly they included heterogeneous populations hindering the applicability of colchicine in this setting.[24,25] Subsequently, few meta-analyses evaluated the influence of colchicine specifically on the incidence of stroke.[26,27,28] The results across these meta-analyses have not been consistent and their statistical precision may have been influenced by including observational studies.[26,27,28] Moreover, these analyses did not include the more recent published studies such as COPS and LoDoCo2 trials.[8,9] Our meta-analysis exclusively incorporates RCTs, including the most recently published COPS and LoDoCo2 trials, and evaluates the effect of colchicine on stroke risk reduction in a relatively homogeneous population of CAD patients.

In addition to the anti-inflammatory properties of colchicine described above, it has been postulated that colchicine might reduce stroke incidence by reducing episodes of AF as suggested by the efficacy of colchicine in preventing AF in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.[29] However, our meta-analysis does not support this mechanism as colchicine did not have influence on the incidence of new-onset/recurrent AF. Importantly, the included studies did not differentiate between the two AF subtypes. Unlike new-onset AF, recurrent AF cannot be reliably used as a surrogate of heightened stroke risk since patients were already receiving oral anticoagulation. While Type II error remains a possibility, our conclusion was driven from the two largest trials of using colchicine in CAD, including more than 10,000 patients. Changes in plaque characteristics in response to colchicine have been recently suggested using computed tomography.[30] The stabilizing effect of colchicine on coronary plaques leading to reduction in MI could be inferred into carotid and aortic plaques, although this hypothesis needs further confirmation. Moreover, it was shown that colchicine can inhibit platelet aggregation in vitro which potentially could reduce thrombus formation and platelet microembolization.[31]

Finally, the lack of significant difference in GI side effects between colchicine and placebo arms reaffirms that colchicine is a well-tolerated medicine which has proven to be safe. This should potentially encourage physicians to prescribe this agent and expecting good tolerance from patients.

Several limitations of the meta-analysis need to be acknowledged. First, the results of the present meta-analysis should be interpreted cautiously as they are derived from the study-level, rather than the patient-level meta-analysis. Second, since all of the RCTs included in the meta-analysis enrolled only a small number of patients with a prior history of transient ischemic attack or stroke, the role of colchicine as secondary prevention following stroke needs to be evaluated in the future. The CONVINCE trial (NCT02898610) will provide further insights into the role of colchicine following stroke. Finally, there was heterogeneity across the included studies when reporting stroke types. The LoDoCo and COPS trials reported the incidence of noncardioembolic strokes, and the stroke mechanism was not specified in the COLCOT or LoDoCo2 trials.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis confirms a statistically significant reduction of stroke in patients with CAD and supports the notion that colchicine is a promising anti-inflammatory agent in preventing strokes when given on a background of optimal medical therapy. Considering its neutral effect on AF occurrence, the clinical benefit is presumably achieved by attenuating inflammation and stabilizing atherosclerotic plaques, although further mechanistic studies are required to confirm these findings.

Declaration of ethical approval and patient consent

This manuscript was exempted from institutional ethical review given it was a meta-analysis. Similarly, patient consent form was not obtained as the published data did not involve individual patients data.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Phipps MS, Cronin CA. Management of acute ischemic stroke. BMJ. 2020;368:l6983. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhalil M. Mechanistic Insights to Target Atherosclerosis Residual Risk. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;46:100432. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhalil M. A promising tool to tackle the risk of cerebral vascular disease, the emergence of novel carotid wall imaging. Brain Circ. 2020;6:81–6. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_65_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caso V, Mas JL. Optimization of stroke prevention: Colchicine may be an option. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1099. doi: 10.1111/ene.14262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1119–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nidorf SM, Eikelboom JW, Budgeon CA, Thompson PL. Low-dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:404–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2497–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nidorf SM, Fiolet AT, Mosterd A, Eikelboom JW, Schut A, Opstal TS, et al. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1838–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong DC, Quinn S, Nasis A, Hiew C, Roberts-Thomson P, Adams H, et al. Colchicine in patients with acute coronary syndrome: The Australian COPS randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2020;142:1890–900. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridker PM, Lüscher TF. Anti-inflammatory therapies for cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1782–91. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajala ON, Everett BM. Targeting inflammation to reduce residual cardiovascular risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020;22:66. doi: 10.1007/s11883-020-00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coca A, Messerli FH, Benetos A, Zhou Q, Champion A, Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. Predicting stroke risk in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease: A report from the INVEST. Stroke. 2008;39:343–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.495465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons LA, Simons J, Friedlander Y, McCallum J. A comparison of risk factors for coronary heart disease and ischaemic stroke: The Dubbo study of Australian elderly. Heart Lung Circ. 2009;18:330–3. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzemczak M, Białek-Ławniczak P, Torzyńska K, Janowska-Kulińska A, Miechowicz I, Kramer L, et al. Comparison of baseline heart rate variability in stable ischemic heart disease patients with and without stroke in long-term observation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:2526–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soler EP, Ruiz VC. Epidemiology and risk factors of cerebral ischemia and ischemic heart diseases: Similarities and differences. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2010;6:138–49. doi: 10.2174/157340310791658785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobiczewski W, Wirtwein M, Trybala E, Gruchala M. Severity of coronary atherosclerosis and stroke incidence in 7-year follow-up. J Neurol. 2013;260:1855–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6892-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng YS, Tan ZX, Wang MM, Xing Y, Dong F, Zhang F. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome: A prospective target for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:155. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrington J, Lemarchand E, Allan SM. A brain in flame; do inflammasomes and pyroptosis influence stroke pathology? Brain Pathol. 2017;27:205–12. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alishahi M, Farzaneh M, Ghaedrahmati F, Nejabatdoust A, Sarkaki A, Khoshnam SE. NLRP3 inflammasome in ischemic stroke: As possible therapeutic target. Int J Stroke. 2019;14:574–91. doi: 10.1177/1747493019841242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma C, Liu S, Zhang S, Xu T, Yu X, Gao Y, et al. Evidence and perspective for the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway in ischemic stroke and its therapeutic potential (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2018;42:2979–90. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridker PM. Interleukin-1 inhibition and ischaemic stroke: Has the time for a major outcomes trial arrived? Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3518–20. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong Y, Ding ZH, Zhan FX, Cai L, Yin X, Ling JL, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome and stroke. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:4787–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemkens LG, Ewald H, Gloy VL, Arpagaus A, Olu KK, Nidorf M, et al. Cardiovascular effects and safety of long-term colchicine treatment: Cochrane review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2016;102:590–6. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma S, Eikelboom JW, Nidorf SM, Al-Omran M, Gupta N, Teoh H, et al. Colchicine in cardiac disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:96. doi: 10.1186/s12872-015-0068-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masson W, Lobo M, Molinero G, Masson G, Lavalle-Cobo A. Role of colchicine in stroke prevention: An updated meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:104756. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katsanos AH, Palaiodimou L, Price C, Giannopoulos S, Lemmens R, Kosmidou M, et al. Colchicine for stroke prevention in patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:1035–8. doi: 10.1111/ene.14198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khandkar C, Vaidya K, Patel S. Colchicine for stroke prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2019;41:582–90.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lennerz C, Barman M, Tantawy M, Sopher M, Whittaker P. Colchicine for primary prevention of atrial fibrillation after open-heart surgery: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017;249:127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaidya K, Arnott C, Martínez GJ, Ng B, McCormack S, Sullivan DR, et al. Colchicine therapy and plaque stabilization in patients with acute coronary syndrome: A CT coronary angiography study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:305–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cimmino G, Tarallo R, Conte S, Morello A, Pellegrino G, Loffredo FS, et al. Colchicine reduces platelet aggregation by modulating cytoskeleton rearrangement via inhibition of cofilin and LIM domain kinase 1. Vascul Pharmacol. 2018;111:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]