Abstract

Many Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) clinics implemented alternatives to in-person service delivery in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including virtual visits and electronic document sharing. The objective of this cross-sectional study was to describe WIC participants’ experiences with remote service delivery and recertification during the pandemic. Participants included mothers and infants who participated in a WIC-based intervention between June 2019-August 2020. All participants (N = 246) were invited to complete a follow-up survey between November 2020-February 2021; 185 mothers completed the survey. The survey assessed sociodemographics, employment, food security, experiences with remote WIC recertification and service delivery, and experiences with obtaining WIC foods during the pandemic. Average age for mothers was 29.2 ± 6.3 years and for infants was 17.7 ± .2 months; 80% (n = 147) identified as Hispanic. Approximately 34% (n = 62) of participants reported very low or low food security and 40% (n = 64) had difficulties buying WIC foods during the pandemic. Among participants who recalled providing documentation of income and address virtually, the majority felt comfortable providing information via email (60%) and text messaging (72%). Participants reported high levels of satisfaction with remote methods of service delivery, as well as overall satisfaction with the WIC program during the pandemic. While ~ 25% of study participants preferred for all WIC services to remain remote, 75% still desired at least some in-person contact with WIC staff after the pandemic. In conclusion, remote methods of WIC service delivery addressed existing barriers to WIC participation and were well-received by study participants.

Keywords: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); COVID-19 pandemic; Program retention; Low-income; Nutrition assistance

Introduction

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is a United States Department of Food and Agriculture (USDA)-funded, critical safety net for low-income pregnant women, new mothers, and their infants and children up to age 5 years [1]. A primary goal of the WIC program is to mitigate nutritional risk during critical windows of development among these vulnerable groups. Traditionally, the WIC program achieves this goal by mandating participants engage in frequent visits to WIC clinics to receive vouchers for healthy foods, nutrition assessments, nutrition education and counseling, and referrals to healthcare and other community services. In the past 5 years, the majority of states converted WIC benefits from paper vouchers to electronic benefits.

Many WIC clinics closed for in-person services indefinitely in March 2020 in response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Stay-at-home and social distancing mandates aimed at mitigating the spread of the disease led to wide-spread closures of businesses and public spaces, including many public services. Within Los Angeles County, California—home to the largest Local Agency WIC Program in the country—all WIC benefits and services transitioned to remote delivery. This change was facilitated by several time-sensitive and temporary federal policy changes enabled by waivers including: (1) the waiving of the physical presence requirement, (2) the ability to remotely issue WIC benefits, and (3) the expansion of the WIC-eligible food list allowed by the USDA.

Although initiated in response to the pandemic, these changes targeted many barriers to WIC participation highlighted by previous, pre-pandemic research [2, 3]. For example, WIC-eligible women are less likely to participate in the WIC program when significant structural barriers are present, such as lack of access to transportation or inabilities to take time off work [3]. In addition, families are required to provide ongoing documentation of their eligibility status (income, address, and nutrition risk) to annually recertify for the WIC program every 12 months. The recertification period when the infant reaches age 1 year is a time when many families do not recertify in WIC, with smaller drops in recertification when children reach ages 2, 3, and 4 years [4]. It is possible that pandemic-related changes to WIC service delivery and recertification processes positively impacted WIC participants by removing barriers, reducing disruptions to food access, and promoting retention within the WIC program during a time of high social and economic distress. However, it is also possible that WIC participants still struggled with accessing WIC-eligible foods and services, as well as with broader significant stressors, such as loss of income due to pandemic-related furloughs, lack of childcare, contraction of COVID-19, and systemic racism. Research is needed to understand mothers’ experiences with pandemic-related changes to WIC service delivery and recertification.

The specific aim of the present study was to understand perceived impacts of WIC policy changes and federal waivers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic on WIC participation, and the nutrition, health, and wellness of mothers and their 1-year-old infants enrolled in the WIC program. Data for this study came from a cohort of mother-infant dyads who participated in a policy, systems, and environmental change (PSE) intervention to promote responsive bottle-feeding among WIC participants. This study was ongoing both prior to and during the pandemic, with study participants’ 1-year recertification period (i.e., when their infant reached 1 year of age) occurring after WIC’s transition to fully remote services. Specifically, in June 2019, 246 WIC mothers with newborn infants were enrolled and provided detailed data about health indicators and WIC experiences at birth and when infants were 3, 6, and 11 months of age. These mothers participated in an additional follow-up assessment during the pandemic (between November 2020–February 2021) to explore the following research questions: (1) What were the perceived impacts of WIC policy changes and federal waivers in response to the pandemic, including waiving requirements for physical presence, issuing benefits remotely, and expanding the WIC-eligible food list, on WIC participation, nutrition, food security, and health outcomes of families with 1-year-olds? and (2) What aspects of these policy changes contributed to improved WIC program access and retention and, if retained, might support ongoing program access post-pandemic?

Methods

Participants

Participants included mothers and infants who participated in a PSE intervention between June 2019 and August 2020. For more details see Ventura et al. [5]. In brief, three WIC clinics were selected to be the clinics within which PSE strategies to support healthy bottle-feeding were implemented (PSE clinics) and three WIC clinics were selected as controls; control clinics were matched to PSE clinics based on WIC participant race/ethnicity, clinic size, and prevalence of breastfeeding. A total of 246 mothers enrolling their newborns into WIC were recruited between June and August 2019 by staff at the participating WIC clinics: 124 dyads were recruited from the 3 PSE clinics (~ 40 per site) and a comparable sample of 122 dyads were recruited from 3 control clinics (~ 40 per site). Eligibility criteria included mothers who were 18 years and older with a newborn, singleton infant born at full-term. Both English and Spanish speaking mothers were included. Exclusion criteria included caregivers to foster children and children who experienced growth faltering, or infants born pre-term. All participants were followed through age 11 months during the parent study; the current study was a fifth survey added in response to the COVID-19 pandemic when infants were 15–22 months in age. All participants, therefore, had to experience the WIC recertification process remotely during the period surrounding their infant’s 1st birthday. This study was reviewed and approved by the California State Committee for Protection of Human Subjects (https://oshpd.ca.gov/data-and-reports/data-resources/cphs/; protocol #: 2019-044-Public Health Foundation Enterprise [PHFE] WIC) and the California Polytechnic State University Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent prior to study participation.

Measures

Data for the present study were collected via Qualtrics, an online survey platform. Participants responded to the survey between November 2020 and February 2021. In addition, WIC administrative data were queried to determine the rate of recertification with WIC among all participants who enrolled in the parent study, regardless of whether they participated in the present study. Because participation in Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) confer adjunctive eligibility in WIC, or the ability of WIC participants to establish income eligibility by simply showing proof of enrollment in other public assistance programs (rather than providing documentation of income and address), WIC administrative data were also queried to determine participation in these programs.

Within the present study, participants reported family demographics, including ethnicity, mothers’ age, education level, marital status, family income level, number of people living in their household, and mothers’ and fathers’ employment status. Participants also reported changes to employment in recent months and whether these changes were due to the pandemic. In addition, participants completed the USDA 6-item Household Food Security Screener [6] to document food security status when the federal waivers in place.

To assess perceived impacts of policy changes and waivers on participation in nutrition assistance programs, participants were queried about whether their family participated in SNAP, when they enrolled in SNAP, whether their child was still enrolled in WIC and, if not, reasons for discontinuation. The research team partnered with the California State Department of Public Health WIC Program to develop a series of questions that assessed participants’ experiences with remote recertification within the WIC program and remote engagement with WIC services. Questions focused on mothers’ experiences with remote WIC recertification, including how comfortable participants felt providing documentation of income and address via various remote methods (e.g., email, text messaging, video conference). Participants also reported their levels of satisfaction with remote methods of WIC service delivery, including phone appointments, interactive texting, online education, and email, as well as overall satisfaction with and perceived quality of WIC during the pandemic. Participants reported their ideal frequency of visiting WIC after the pandemic, as well as the services they most looked forward to receiving in-person. To assess perceived impacts of policy changes and waivers on food security, participants were queried about experiences with obtaining WIC-eligible foods during the pandemic, their knowledge and understanding of expanded WIC food lists made possible through federal waivers, and whether this list or the California WIC App helped with access to food during the pandemic. Survey questions are available upon request.

Statistical Analysis

All 246 participants in the original sample were invited to participate in the COVID follow-up survey; 185 completed the survey. All analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize participants’ responses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 represents sample characteristics. Participants were primarily Hispanic. Average age for mothers was 29.2 ± .3 years and for their infants was 17.7 ± .2 months. Most mothers reported that they had some college or an associate’s, undergraduate, or graduate degree (61%) and a majority were married (60%). Approximately 37% of mothers reported a family income of < $1200 per month and 8% of the mothers reported they had two to six people living in their household.

Table 1.

Frequency (%) for demographic characteristics of low-income mothers who participated in the WIC program during their first year postpartum (n = 185)

| Ethnicity | |

| Not Hispanic | 35 (18.9) |

| Hispanic | 147 (79.5) |

| Not reported | 3 (1.6) |

| Preferred language | |

| English | 155 (83.8) |

| Spanish | 30 (16.2) |

| Education level | |

| Less than high school | 25 (13.5) |

| High school degree | 47 (25.4) |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 88 (47.6) |

| College or graduate degree | 25 (13.5) |

| Presence of partner/spouse | |

| Had partner or spouse | 110 (59.5) |

| Did not have partner or spouse | 74 (40.0) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.5) |

| Family income level | |

| < $1200/monthly | 69 (37.3) |

| $1200 to $1800/monthly | 50 (27.0) |

| $1800 to $2400/monthly | 36 (19.5) |

| < $2400/monthly | 12 (6.5) |

| Not known | 18 (9.7) |

| Number of people in household | |

| 2 to 6 people | 150 (81.0) |

| 7 to 12 people | 21 (11.4) |

| Not reported | 14 (7.6) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 37 (20.0) |

| Part-time | 41 (22.2) |

| Not working | 107 (57.8) |

| Employment status of partner/spousea | |

| Full-time | 50 (45.5) |

| Part-time | 32 (29.1) |

| Not working | 25 (22.7) |

| Not reported | 3 (2.7) |

| Food security | |

| Very low food security | 21 (11.4) |

| Low food security | 41 (22.1) |

| Moderate to high food security | 122 (65.9) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.5) |

| Participating in SNAP | |

| Yes | 71 (38.4) |

| No | 106 (57.3) |

| Not reported | 8 (4.3) |

SNAP Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, WIC Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

an = 110

42% (n = 78) of participants reported they were employed part- or full-time and 39% (n = 73) worked in an industry considered an essential service during the pandemic. Approximately 8% (n = 14) of participants reported they were working more during the pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic, 50% (n = 92) reported working less, and 41% (n = 76) about the same. Among the 58% (n = 107) of participants who reported they were not working, 41% (n = 44) reported they were not working because of reasons related to the pandemic. Participants also reported their spouse or partner’s employment status; 75% (n = 82) of participants with a spouse or partner reported their spouse/partner was employed part- or full-time, with 7% (n = 8) of spouse/partners working more during the pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic, 53 % (n = 58) working less, and 32% (n = 35) working about the same. 23% (n = 25) of participants reported their partners were not working, with 80% (n = 20) of unemployed partners not working because of reasons related to the pandemic. Approximately 34% (n = 62) of participants reported their family was experiencing very low or low food security. 38% (n = 71) of participants reported they also participated in SNAP; 59% (n = 42) of these participants reported they enrolled in SNAP prior to the pandemic, whereas 35% (n = 25) reported they enrolled after the pandemic.

Experiences with Recertification with WIC During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Of the 246 participants who enrolled in the parent study, 4 no longer qualified for WIC and 4 moved out of state and their WIC status was unknown. Of the remaining 238 participants, 85% (n = 202) recertified their infants at 1 year and 15% (n = 36) did not. 68% (n = 138) were enrolled in other public assistance programs, thus recertified via adjunctive eligibility.

Among the subset of 185 participants who completed the COVID follow-up survey, 88% (n = 163) reported their child still received WIC benefits at the time they completed the survey and 7% (n = 13) reported their child no longer received WIC benefits; 5% (n = 9) of participants did not respond to this question. Among the 13 participants who reported their children were no longer receiving WIC, reasons for discontinuation of WIC participation included: not needing WIC anymore (n = 3), not being able to reach WIC due to pandemic-related site closures (n = 1), not feeling comfortable sharing personal information over the phone or by text/email (n = 2), no longer qualifying for WIC (n = 3), and moving to a new area or out of state (n = 2).

Slightly over one-third of participants (36%, n = 63) recalled providing documentation of income and address to WIC since March 2020, when WIC sites physically closed. Table 2 reports the methods by which participants provided documentation of income and address (e.g., email, text messaging) during the pandemic, as well as participants’ comfort levels with sharing their information via these methods. Among participants who reported sharing information via email and text messaging, the majority reported feeling comfortable or somewhat comfortable providing information via email (87%) and text messaging (83%). Only 4 participants reported feeling somewhat uncomfortable and no participants reported being uncomfortable with email or text messaging to share personal information. Only one participant reported sharing information via video conference and this participant reported feeling somewhat comfortable with this method.

Table 2.

Frequency (%) for reported method and level of comfort with WIC income documentation methods during the COVID-19 pandemic for low-income mothers (n = 63)

| n (%) experiencing each method | Level of comfort with each method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfortable | Somewhat comfortable | Somewhat uncomfortable | Uncomfortable | ||

| 15 (23.8) | 9 (60.0) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | |

| Text messages | 29 (46.0) | 21 (72.4) | 6 (20.7) | 2 ( 6.9) | 0 |

| Video conference | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Other methods | 14 (22.2) | 11 (78.6) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) |

COVID-19 coronavirus-19; WIC Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Experiences with WIC Service Delivery Methods During the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the pandemic, many WIC services that would typically be delivered in-person were instead delivered via a wide variety of remote methods, including phone appointments, interactive texting with WIC staff, online education, email, and video appointments. Table 3 reports participants’ reported levels of satisfaction with these various WIC service delivery methods. Among participants experiencing each method of service delivery, most reported high levels of satisfaction with phone appointments (96%), interactive texting (96%), online education (94%), email (93%), and video appointments (80%).

Table 3.

Frequency (%) for reported experiences and level of satisfaction with WIC service delivery methods during the COVID-19 pandemic for low-income mothers (n = 185)

| n (%) experiencing each method | Level of satisfaction with each method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very or mostly satisfied | Neutral | Not very or not at all satisfied | ||

| Phone appointment | 160 (86.5) | 153 (95.6) | 4 (2.5) | 3 (1.8) |

| Interactive texting | 151 (81.6) | 145 (96.0) | 3 (2.0) | 3 (1.9) |

| Online education | 139 (75.1) | 130 (93.5) | 7 (5.0) | 2 (1.2) |

| 106 (57.3) | 98 (92.5) | 4 (3.8) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Video appointment | 76 (41.1) | 61 (80.3) | 10 (13.2) | 5 (3.1) |

WIC Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Regarding overall satisfaction with WIC during the pandemic, most participants (85%, n = 157) reported that they felt satisfied with WIC most of the time or always. Most participants (84%, n = 156) rated the quality of WIC services as being the same or better since before the pandemic. Most participants whose infants were still participating in WIC (n = 154/163, 94%) reported they were somewhat or very likely to continue their WIC participation when WIC centers reopened for in-person services and most (n = 143/163, 88%) also reported they would keep coming back to WIC until their child reached 4 or 5 years of age.

Desire for In-Person WIC Services After the COVID-19 Pandemic

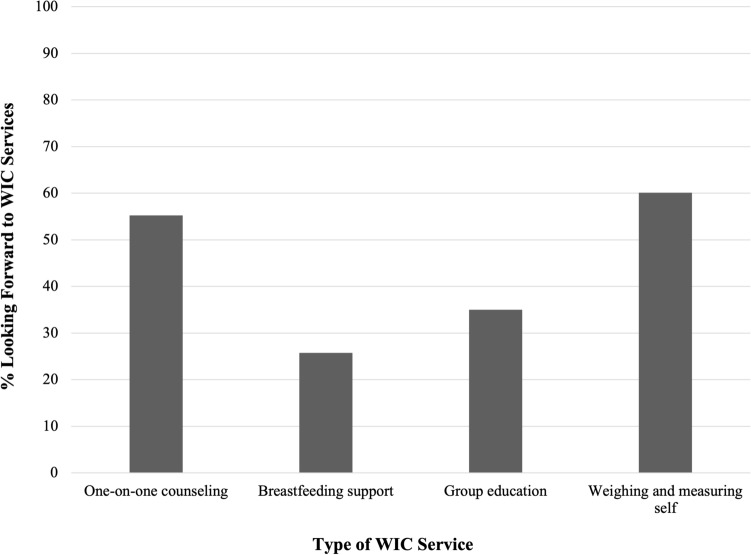

41% of participants whose infants were still participating in WIC (n = 67/163) indicated their ideal frequency of visiting WIC centers to receive in-person services would be every 3 months. 24% (n = 39) indicated they would prefer for services to remain remote. 17% (n = 28) preferred every 6 months, 9% (n = 15) every month, and 2% (n = 3) every year. Figure 1 presents the percentage of these participants who reported they looked forward to receiving the different in-person WIC services when safe to do so. 60% (n = 98) of participants reported they looked forward to weighing and measuring themselves and 55% (n = 90) looked forward to receiving one-on-one counseling in-person services. Fewer participants reported looking forward to group education (35%, n = 57) and breastfeeding support (26%); only 18% (n = 33) of participants were still breastfeeding their infant at the time of the survey.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of WIC participants looking forward to receiving in-person services when safe

Experiences with Purchasing WIC Foods During the COVID-19 Pandemic

At the onset of the pandemic in the U.S., WIC temporarily modified and expanded WIC-eligible foods. Participants who reported their infants were still receiving WIC (n = 163) reported their experiences purchasing WIC food during the pandemic. Most participants reported that they purchased WIC-approved foods in large stores (54%, n = 83) and WIC-stores (41%, n = 67); only 7% (n = 12) of participants reported they purchased WIC-approved foods in small stores. Many participants (58%, n = 94) reported that they did not experience difficulties purchasing WIC foods because they were not available at the store; however, 40% (n = 64) of participants experienced challenges buying WIC foods currently (10%, n = 16) or in the past (29%, n = 48). Regarding WIC food benefits, most participants (81%, n = 132) reported not having any problems understanding when their WIC benefits were available for their use. Most participants (82%, n = 133) reported that the CA WIC App helped them understand which foods they could buy with their WIC card. Some participants reported that the app was helpful, but they could not purchase things on their card (n = 19), 4 participants reported that the app was not useful, and 7 participants did not use the app.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic created novel challenges to addressing food insecurity through nutrition assistance programs, such as WIC. Stay-at-home and social distancing mandates disrupted traditional methods of service delivery, including in-person clinic visits and sharing of physical documents for program recertification. In response, many WIC clinics implemented under-utilized alternatives to in-person service delivery, such as virtual visits and electronic document sharing, which allowed for quick adaptation to the disruptions imposed by the pandemic. A potential benefit of these alternatives is that they addressed existing barriers to WIC participation; thus, the pandemic provided a unique opportunity to evaluate WIC participants’ experiences with and reactions to alternative forms of WIC service delivery. To this end, the present study aimed to evaluate WIC participants’: (1) perceived impacts of pandemic-related changes to WIC service delivery and (2) experiences and satisfaction with WIC program access during the pandemic.

A distinctive feature of this study is that it captured WIC participants’ experiences with the recertification process during a historical time of crisis and transition. Per federal regulations, WIC participants are required to recertify their infant into the WIC program at 1 year of age. Prior to the pandemic, WIC participants recertified during an in-person meeting with WIC staff wherein they provided proof of income and address or proof of enrollment in other public assistance programs. However, this imposed many barriers to WIC participation, such as the need for transportation, potentially long wait times, and the need to take time away from work [7, 8]. Slightly over one-third of study participants recalled providing documentation of income and address after pandemic-related shut-downs; the research team verified via WIC administrate data that all study participants who reported their infant still received WIC benefits provided documentation of eligibility virtually, but the majority did so via adjunctive eligibility, or the ability of WIC participants to establish income eligibility by showing proof of enrollment in other public assistance programs, such as Medicaid, TANF, or SNAP [9, 10]. Given most WIC families are also enrolled in Medicaid, the ability of WIC Information Systems to interface directly with Medicaid records is an important tool for reducing barriers to ongoing WIC participation [9, 11].

For the one-third of participants who recalled providing documentation of income and address, the majority felt comfortable sharing their information through virtual methods, including sharing information via email, text messaging, or video conferencing. These perceptions are promising and consistent with previous research illustrating adults generally feel comfortable sharing personal information virtually to receive benefits or services [12]. Given the omnipresence of digital technology and virtual modes of communication [13], sharing of personal information via virtual methods is likely a common experience for many adults. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that WIC participants will continue to feel comfortable with sustained use of virtual methods for recertification after the pandemic. These virtual methods also likely reduced barriers to WIC participation that existed prior to the pandemic.

Indeed, over 80% of participants in the parent study and almost 90% of participants in the present study reported their child still received WIC benefits. Although this probably reflects greater levels of need due to pandemic-related job losses and food insecurity, these high rates of recertification also suggest that alternative modes of recertification and service delivery implemented in response to the pandemic did not negatively impact rates of WIC participation. This high prevalence of recertification is promising and consistent with other reports of relatively higher rates of recertification during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic [14]. Prior to the pandemic, WIC caseloads were declining with particularly concerning declines in coverage rates, defined as the prevalence of eligible infants and toddlers participating in WIC [15, 16]. In 2017, only ~ 50% of eligible 1-year-olds were participating in WIC, meaning that a large portion of children in need were not experiencing the well-documented benefits of WIC [3, 17–20]. Striking increases in WIC recertification in California during the pandemic suggest families in need remained in WIC at higher rates than usual, which may have decreased gaps in coverage rates. In addition, findings from the present study suggest that efforts to make WIC more accessible during the pandemic were well-received by these families.

Most study participants indicated that they were satisfied with new modes of WIC engagement, including phone appointments, interactive texting, online education, email, and video conferencing. 85% of study participants reported they were satisfied with their experiences with WIC during the pandemic and most thought the quality of services was the same or better. Given satisfaction with WIC is a strong predictor of WIC retention [21], these perceptions likely underlined study participants’ reports that they were likely to continue with WIC after the pandemic and until their child’s 4th or 5th birthday. Continued efforts to assess and promote participants’ feelings of satisfaction with WIC are imperative. Efforts to promote satisfaction should consider maintenance of these alternative modes of WIC engagement given study participants’ favorable views of and experiences with them.

About 25% of study participants reported they would prefer for WIC services to remain fully remote; thus, it is notable that three-quarters of study participants still desired some in-person contact with WIC staff after the pandemic. Services that participants looked forward to receiving in-person included the ability to weigh and measure themselves and their children and engaging in one-on-one counseling services. That fewer participants reported looking forward to group education and breastfeeding support may reflect the fact that WIC already offered extensive online nutrition education before the pandemic and that very few participants in this sample were still breastfeeding. Taken together, these perceptions suggest that study participants responded favorably to remote service and still perceived value in in-person visits. Further research is needed to identify the specific aspects of in-person visits that are most valuable to WIC participants so these aspects can be promoted and preserved to enhance WIC participants’ experiences and satisfaction.

Prior to the pandemic, a primary driver of WIC participants’ satisfaction with WIC was their ability to access WIC-eligible foods. WIC participants often experience challenges finding WIC-eligible foods when shopping at grocery stores and face stigmatization when attempting to use their WIC benefits during store checkout [22, 23]. At the onset of the pandemic, disruptions to food supply chains and availability likely compounded challenges to WIC participants’ abilities to access WIC-eligible foods. In the present study, 60% of study participants reported that they did not experience difficulties purchasing WIC foods because they were not available at the store. However, it is concerning that a significant proportion (40%) experienced challenges buying WIC foods during the pandemic. In addition, approximately one-third of participants reported their family experienced very low or low food security during the pandemic and most participants and/or their spouses were working less than usual or not at all because of the pandemic. Thus, like much of the world, participants in the present study experienced negative impacts of the pandemic on their employment, financial, and food security [24]. Taken together, these findings underline the need for robust measures to protect WIC participants’ abilities to access WIC foods within retail settings, especially during times of economic and public health instability. Fortunately, most participants did not report they had difficulty understanding when their WIC benefits were available for their use. Most also reported that the California WIC App helped them understand which foods they could buy with their WIC card. These findings suggest the tools provided by WIC are effective for helping participants understand their benefits and liaison between WIC and food retailers may be necessary to ensure that all WIC participants can easily access WIC-eligible foods during their retail experiences.

A strength of this study was the use of an existing cohort of WIC families who had participated in WIC since the infant’s birth and had previously been engaged in a research study, which facilitated the ability to collect additional information after the unexpected changes to WIC during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was also well-positioned to examine the point in the WIC eligibility window (the infant’s 1st birthday) where the most substantial drop-off in WIC participation has been documented [4]. An additional study strength was the use of both survey and WIC administrative data: while 75% of the sample responded to the survey, the research team could account for the WIC participation status, recertification, and use of other public assistance programs for all but 8 of the original sample of 246. Limitations included those that are common to survey-based research, most importantly the fact that many participants did not recall that they had to report their income and address information virtually and therefore were not asked about their experiences with providing that information remotely. Although this may able been attributable to adjunctive eligibility, it may also reflect recall bias. However, if due to recall bias, it is promising that participants remote provision of income and address documentation was not a memorably negative experience or significant barrier for WIC participants. Finally, this sample was predominantly Hispanic and lived in California, so results are not necessarily representative of the entire WIC population.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

California experienced an unprecedented increase in WIC participation at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic [14]. Findings from the present study suggest remote services, made possible due to Federal Waivers from the USDA, helped facilitate ongoing WIC participation for families in need of supplemental food for their 1-year-old infants. In addition, provision of remote services in response to the COVID-19 pandemic was essential for low-income families to maintain access to healthy WIC foods. While approximately one-quarter of study participants reported they preferred for WIC services to remain remote, three-quarters still desired some in-person contact with WIC staff after the pandemic. This speaks to the need for a hybrid model of WIC service delivery as the pandemic resolves, with some services continuing remotely and others provided in-person, as it becomes safe to do so. While the pandemic brought significant challenges to low-income families, the opportunities it afforded by requiring service delivery in new and creative ways are many. Now is the time to continue to expand upon these opportunities and continue to modernize WIC service delivery for the 21st century.

Acknowledgements

We thank the mothers and infants who participated in this study. We also thank Martha Meza, Elizabeth Rodriguez, Jocelyn Gee, Abigail Ecal, Basia Mierzwinski, and Karina Silva Garcia for their technical assistance. Permission was received from all named.

Author Contributions

AKV and SW designed the study, oversaw all aspects of data collection, management, and analysis, and reviewed, revised, and finalized the manuscript. CEM assisted with study design and execution, data collection and data management and reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding

The project described was supported by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Healthy Eating Research grant (Grant No. 76293).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code Availability

All study code is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the California State Committee for Protection of Human Subjects (https://oshpd.ca.gov/data-and-reports/data-resources/cphs/; protocol #: 2019-044-Public Health Foundation Enterprise [PHFE] WIC) and the California Polytechnic State University Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided informed consent prior to study participation.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alison K. Ventura, Email: akventur@calpoly.edu

Catherine E. Martinez, Email: CatherineM@phfewic.org

Shannon E. Whaley, Email: shannon@phfewic.org

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Frequently asked questions. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/frequently-asked-questions. Accessed 19 July 2021.

- 2.Gilbert D, Nanda J, Paige D. Securing the safe net: Concurrent participation in income eligible assistance programs. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2014;95:128–132. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu CH, Liu H. Concerns and structural barriers associated with WIC participation among WIC-eligible women. Public Health Nursing. 2016;33(5):395–402. doi: 10.1111/phn.12259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2019). National and state-level estimates of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) eligibility and WIC program reach in 2017. Alexandria, VA: USDA Food and Nutrition Service. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/national-and-state-level-estimates-wic-eligibility-and-wic-program-reach-2017. Accessed 3 June 2021.

- 5.Ventura AK, Silva Garcia K, Meza M, Rodriguez E, Martinez CE, Whaley SE. Promoting responsive bottle-feeding within WIC: Evaluation of a Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change Approach. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickel, G., Nord, M., Price, C., Hamilton, W., & Cook, J. (2000). Guide to measuring household food security, revised 2000. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Alexandria, VA. https://alliancetoendhunger.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/USDA-guide-to-measuring-food-security.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2021.

- 7.Woelfel ML, Abusabha R, Pruzek R, Stratton H, Chen SG, Edmunds LS. Barriers to the use of WIC services. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104(5):736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekhobo JP, Peck SR, Byun Y, et al. Use of a mixed-method approach to evaluate the implementation of retention promotion strategies in the New York State WIC program. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2017;63:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National WIC Association. (2015). WIC and adjunctive eligibility. Washington, D.C.: National WIC Association. https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws.upl/nwica.org/wic-adjunctive-eligibilitya.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2021.

- 10.National Research Council . Estimating eligibility and participation for the WIC Program: Final report. National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson, S., Neuberger, Z., & Rosenbaum, D. (2017). WIC participation and costs are stable. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wic-participation-and-costs-are-stable. Accessed 19 July 2021.

- 12.Rainie, L., & Duggan, M. (2016). Privacy and information sharing: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/01/14/privacy-and-information-sharing/. Accessed 5 June 2021.

- 13.Anderson, M. (2019). Mobile technology and home broadband, 2019. https://www.pewinternet.org/2019/06/13/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2019/. Accessed 5 June 2021.

- 14.Whaley SE, Anderson CE. The importance of federal waivers and technology in ensuring access to WIC during COVID-19. American Journal of Public Health. 2021;111(6):1009–1012. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2021.306211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Food and Nutrition Service, United States Department of Agriculture. (2017). WIC 2017 eligibility and coverage rates. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic-2017-eligibility-and-coverage-rates. Accessed 19 July 2021.

- 16.Oliveira, V. (2017). WIC participation continues to decline: Economic Research Services, United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2017/june/wic-participation-continues-to-decline/. Accessed 19 July 2021.

- 17.Bitler MP, Currie J. Does WIC work? The effects of WIC on pregnancy and birth outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2005;24(1):73–91. doi: 10.1002/pam.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gai F, Feng L. Effects of federal nutrition program on birth outcomes. International Atlantic Economic Society. 2012;40(1):61–83. doi: 10.1007/s11293-011-9294-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nestor B, McKenzie J, Hasan N, AbuSabha R, Achterberg C. Client satisfaction with the nutrition education component of the California WIC program. Journal of Nutrition Education. 2001;33:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen AL, Owen GM. Twenty years of WIC: A review of some effects of the program. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1997;97:777–782. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(97)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food Research & Action Center. (2019). Making WIC work better: Strategies to reach more wome and children to strengthen benefits use. Washington, DC: Food Research & Action Center. https://frac.org/research/resource-library/making-wic-work-better-strategies-to-reach-more-women-and-children-and-strengthen-benefits-use. Accessed 19 July 2021.

- 22.Chauvenet C, De Marco M, Barnes C, Ammerman AS. WIC recipients in the retail environment: A qualitative study assessing customer experience and satisfaction. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2019;119(3):416–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almeida R, Alvarez Gutierrez S, Whaley SE, Ventura AK. A qualitative study of breastfeeding and formula-feeding mothers’ perceptions of and experiences in WIC. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2020;52(6):615–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Congressional Research Service. (2021). Unemployment rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Washington, D.C.R46554. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R46554.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

All study code is available upon request to the corresponding author.