Abstract

Background

Physical activity among children and adolescents is associated with lower adiposity, improved cardio‐metabolic health, and improved fitness. Worldwide, fewer than 30% of children and adolescents meet global physical activity recommendations of at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day. Schools may be ideal sites for interventions given that children and adolescents in most parts of the world spend a substantial amount of time in transit to and from school or attending school.

Objectives

The purpose of this review update is to summarise the evidence on effectiveness of school‐based interventions in increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity and improving fitness among children and adolescents 6 to 18 years of age.

Specific objectives are:

• to evaluate the effects of school‐based interventions on increasing physical activity and improving fitness among children and adolescents;

• to evaluate the effects of school‐based interventions on improving body composition; and

• to determine whether certain combinations or components (or both) of school‐based interventions are more effective than others in promoting physical activity and fitness in this target population.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, BIOSIS, SPORTDiscus, and Sociological Abstracts to 1 June 2020, without language restrictions. We screened reference lists of included articles and relevant systematic reviews. We contacted primary authors of studies to ask for additional information.

Selection criteria

Eligible interventions were relevant to public health practice (i.e. were not delivered by a clinician), were implemented in the school setting, and aimed to increase physical activity among all school‐attending children and adolescents (aged 6 to 18) for at least 12 weeks. The review was limited to randomised controlled trials. For this update, we have added two new criteria: the primary aim of the study was to increase physical activity or fitness, and the study used an objective measure of physical activity or fitness. Primary outcomes included proportion of participants meeting physical activity guidelines and duration of moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time (new to this update). Secondary outcomes included measured body mass index (BMI), physical fitness, health‐related quality of life (new to this update), and adverse events (new to this update). Television viewing time, blood cholesterol, and blood pressure have been removed from this update.

Data collection and analysis

Two independent review authors used standardised forms to assess each study for relevance, to extract data, and to assess risk of bias. When discrepancies existed, discussion occurred until consensus was reached. Certainty of evidence was assessed according to GRADE. A random‐effects meta‐analysis based on the inverse variance method was conducted with participants stratified by age (children versus adolescents) when sufficient data were reported. Subgroup analyses explored effects by intervention type.

Main results

Based on the three new inclusion criteria, we excluded 16 of the 44 studies included in the previous version of this review. We screened an additional 9968 titles (search October 2011 to June 2020), of which 978 unique studies were potentially relevant and 61 met all criteria for this update. We included a total of 89 studies representing complete data for 66,752 study participants. Most studies included children only (n = 56), followed by adolescents only (n = 22), and both (n = 10); one study did not report student age. Multi‐component interventions were most common (n = 40), followed by schooltime physical activity (n = 19), enhanced physical education (n = 15), and before and after school programmes (n = 14); one study explored both enhanced physical education and an after school programme. Lack of blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors and loss to follow‐up were the most common sources of bias.

Results show that school‐based physical activity interventions probably result in little to no increase in time engaged in moderate to vigorous physical activity (mean difference (MD) 0.73 minutes/d, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.16 to 1.30; 33 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence) and may lead to little to no decrease in sedentary time (MD ‐3.78 minutes/d, 95% CI ‐7.80 to 0.24; 16 studies; low‐certainty evidence). School‐based physical activity interventions may improve physical fitness reported as maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) (MD 1.19 mL/kg/min, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.82; 13 studies; low‐certainty evidence). School‐based physical activity interventions may result in a very small decrease in BMI z‐scores (MD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.09 to ‐0.02; 21 studies; low‐certainty evidence) and may not impact BMI expressed as kg/m² (MD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.01; 50 studies; low‐certainty evidence). We are very uncertain whether school‐based physical activity interventions impact health‐related quality of life or adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

Given the variability of results and the overall small effects, school staff and public health professionals must give the matter considerable thought before implementing school‐based physical activity interventions. Given the heterogeneity of effects, the risk of bias, and findings that the magnitude of effect is generally small, results should be interpreted cautiously.

Plain language summary

Do school‐based physical activity interventions increase moderate to vigorous physical activity and improve physical fitness among children and adolescents?

Key messages

School‐based interventions may improve physical fitness but may have little to no impact on body mass index (which is used to assess whether body weight is in a healthy range), although we do not have confidence in the evidence.

Very few studies have reported on any potential harmful effects.

Careful consideration is needed about the type of school‐based physical activity programme to be implemented, and future studies should seek to identify the best types of physical activity interventions for school settings.

Why is it important to promote physical activity in children?

It is estimated that as many as 5.3 million deaths worldwide are caused by not getting enough exercise (physical inactivity), and this is a big risk factor leading to most long‐lasting diseases and cancers. This is a topic of concern, particularly because it is known that physical activity patterns in childhood can lead to similar patterns in adulthood. Programmes that encourage children to exercise while at school are thought to be a way to increase activity levels of all children, regardless of other factors such as parent behaviours and social or financial factors of a child’s early lifetime.

What did we find?

We found 89 studies that looked at the effects of programmes in schools that focused on increasing physical activity, which included 66,752 children and adolescents (between the ages of 6 and 18) from around the world. The length of programme time varied from 12 weeks to 6 years. No two school‐based physical activity programmes used the same combination of intervention parts. How often and how long each part of a programme was run varied a lot across studies.

Across all included studies, only very small changes were noted in the number of students undertaking physical activity or in minutes per day of moderate to vigorous physical activity or sedentary time, although these programmes were found to improve students’ physical fitness. These programmes were found to have little to no impact on measurements used to assess whether body weight is in a healthy range. Not many studies reported on any potential harmful effects, such as injury or psychological harm.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We have little confidence in the evidence because studies were done in different ways and interventions were delivered and assessed in different ways. Also, people in the studies may have been aware of which interventions they were getting, and this can sometimes affect the outcomes reported. In addition, not all studies provided data about everything we were interested in.

How up‐to‐date is the evidence?

The evidence is up‐to‐date to June 2020 (although we did run a new search for studies in February 2021 and found studies that may be included in a future update and are now described in the “Studies awaiting classification” table).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. School‐based physical activity programmes for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years.

| School‐based physical activity programmes for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years | ||||

|

Population: children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years Settings: primarily within the school setting Intervention: educational, health promotion, counselling, and management strategies focused on promotion of physical activity and fitness Comparison: standard, currently existing physical education programmes in schools | ||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated effects (95% CI) | No. of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with control | Risk with intervention | |||

|

% of participants physically active

[follow‐up: 12 weeks to 12 months] |

% physically active ranged from 2% to 50% | % physically active ranged from 1.11% lower to 12.22% higher. | 6,068 (5) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa |

|

Moderate to vigorous physical activity (minutes/d) [follow‐up: 12 weeks to 3 years] |

‐3.63 (‐5.03 to ‐2.23) | MD 0.73, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.30 | 20,614 (33) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb |

| Sedentary time (minutes/d) [follow‐up: 12 weeks to 28 months] | 27.77 (‐21.34 to 76.88) | MD ‐3.78, 95% CI ‐7.80 to 0.24 | 11,914 (16) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowc |

| Physical fitness (VO₂ max, mL/kg/min) [follow‐up: 12 weeks to 1 year] | ‐1.00 (‐1.59 to ‐0.41) | MD 1.19, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.82 | 3,980 (13) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd |

| BMI (z‐score) [follow‐up: 12 weeks to 4 years] | ‐0.01 (‐0.08 to 0.06) | MD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.09 to ‐0.02 | 22,948 (21) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowe |

| BMI (kg/m²) [follow‐up: 12 weeks to 4 years] | ‐0.35 (‐1.06 to 0.36) | MD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.01 | 34,337 (50) |

|

|

Health‐related quality of life [follow‐up: 15 weeks to 12 months] |

Not estimable; insufficient data reported within studies | 4,687 (7) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowf |

|

|

Adverse events [follow‐up: 12 weeks to 3 years] |

Not estimable; only 3 studies reported any adverse events | 11,698 (16) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowg |

|

| BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; min/d: minutes per day; VO₂max: maximal oxygen uptake. | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the effect estimate. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||

aDowngraded by one level each for inconsistency (large variation in effects across studies), imprecision (wide confidence intervals), and risk of bias (high or unclear in most studies).

bDowngraded by one level for inconsistency (visual inspection of forest plots and I² value from meta‐analysis).

cDowngraded by one level for imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals) and risk of bias (high or unclear in many studies).

dDowngraded by one level for inconsistency (visual inspection of forest plots and I² value from meta‐analysis) and indirectness (estimated vs measured VO₂ peak).

eDowngraded by one level for inconsistency (visual inspection of forest plots and I² value from meta‐analysis), risk of bias (high or unclear in most studies).

fDowngraded by one level for inconsistency (large variation across studies), risk of bias (high or unclear in most studies), publication bias (most studies not reporting on health‐related quality of life or describing full results).

gDowngraded by one level for inconsistency (large variation across studies), publication bias (most studies not reporting on adverse events or methods for monitoring), risk of bias (high or unclear in most studies).

Background

Description of the condition

International public health and health promotion organisations have identified health risks across the lifespan associated with physical inactivity. Recent estimates suggest that 5.3 million deaths per year throughout the world are attributable to physical inactivity (Lee 2012a). Globally, physical inactivity has been identified as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality (6% of all deaths), following high blood pressure, tobacco use, and high blood glucose, and overweight and obesity are responsible for 5% of deaths globally (Warburton 2017; WHO 2008). Physical inactivity is estimated to cause 10% of the burden of disease from breast cancer and colon cancer, as well as 7% from type 2 diabetes, and 6% from coronary heart disease (Lee 2012a). The burden of these and other chronic diseases has rapidly increased in recent decades (WHO 2008). In fact, physical activity was labelled as “today's best buy in public health” almost three decades ago (Morris 1994). Recent estimates suggest that physical inactivity cost healthcare systems $ (INT$) 53.8 billion worldwide in 2013 (Ding Ding 2016). In addition, the literature indicates that an elevated body mass index (BMI) places children and adolescents at greater risk for cardiovascular disease as adults, and that diet and physical activity are important factors in maintaining a healthy BMI range (Hills 2011). Longitudinal data have shown that for each weekday that adolescents of normal weight participated in physical education (PE), the odds of becoming overweight in adulthood decreased by 5% (Menschik 2008).

Previous reports have concluded that the intensity, frequency, and duration of physical activity contribute to overall physical health status and suggest that a 'threshold' must be maintained to produce positive health effects (CDC 1999; Shephard 1997; Tolfrey 2000). In fact, a positive linear association between duration of physical activity and positive health effects has been established, with longer duration associated with improved physical health (Carson 2017; Janssen 2010; Shephard 1997). Maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) is a standard measure associated with fitness levels, with increasing values expected as fitness level improves, and is an important indicator of successful physical activity interventions. Recent analyses have shown a dose‐response relationship between physical activity behaviours (minutes/week of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA)) and fitness levels (measured by VO₂max) and measures of cardio‐metabolic health, including measures of body composition, blood pressure, and blood cholesterol (Nevill 2020; Sriram 2021).

Current guidelines suggest that children and adolescents should engage in at least 60 minutes of MVPA per day, along with muscle and bone strengthening activities at least 3 days per week (Chaput 2020). Examples of moderate to vigorous activities include brisk walking, jogging, stair climbing, basketball, racquet sports, soccer, dance, lap swimming, skating, strength training, cross‐country skiing, and cycling. In the most recently released global physical activity guidelines, evidence suggests that time spent in sedentary behaviour is associated with poorer health outcomes in both children and adolescents, and it is recommended that children and adolescents limit sedentary time, especially when sedentary time is combined with recreational screen time (Chaput 2020). Research suggests that the best primary strategy for improving the long‐term health of children and adolescents through exercise may involve creating a lifestyle pattern of regular MVPA that will carry over to the adult years (Freedson 1992; Telama 2005; Twisk 2000). Despite this, the Global Matrix 3.0 Physical Activity Report Card Grades for Children and Youth on physical levels of children and youth from 49 countries revealed a mean letter grade of C for the percentage of children and youth meeting the physical activity recommendation of 60 minutes of MVPA per day, representing 27% to 33% of children and youth (Aubert 2018). Therefore it is of primary importance to identify approaches that will be effective in increasing and sustaining activity levels of children and adolescents in places where they spend long periods of time, such as schools.

Description of the intervention

To ensure sustained progress towards major improvements in chronic disease prevention, the World Health Organization (WHO) has called on public health organisations within and between countries to work collaboratively with key partners, including educators and health professional bodies, educational institutions, consumer groups, researchers, and the private sector, to provide a comprehensive strategy to promote physical activity among children and adolescents (WHO 2008). The school setting is an ideal environment for population‐based physical activity interventions, as no other institution has as much influence on children during their first two decades of life (Naylor 2009; Story 2009). Recognising the unique opportunity that exists to formulate and implement an effective strategy to substantially reduce deaths and disease burden worldwide by improving diet and promoting physical activity, the WHO has adopted the Health Promoting School (HPS) framework to promote healthy living, learning, and working conditions. An HPS encourages moving beyond individual behaviour change and considering and addressing the whole‐school environment (IUHPE 2010). The WHO specifically identified schools as a target setting for promotion of physical activity among children and youth and suggested that schools implement opportunities and programming for physical activity and provide safe and appropriate spaces that facilitate participation in physical activity (WHO 2008).

Schools are considered an ideal setting for promoting physical activity among children due to their broad reach and multiple opportunities to promote physical activity over the course of the school week, including physical education classes, before and after school programmes, recess programming, active school travel, and classroom‐based physical activity (Singh 2017; Watson 2017a). To effectively promote MVPA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that schools engage in comprehensive approaches to develop, implement, and evaluate physical activity policies and practices; establish school environments that support physical activity; implement a quality physical activity programme with quality physical education as a cornerstone; implement health education that provides students with the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed for physical activity; provide students with health, mental health, and social services to promote physical activity and prevent chronic disease; partner with families and community members in development and implementation of physical activity policies; provide a school employee wellness programme that includes physical activity services for all school staff members; and employ qualified persons and provide professional development opportunities for physical education and physical activity (CDC 2011).

Studies conducted to date have generally utilised different combinations of physical activity promotion interventions in schools, including before and after school programmes, multi‐component physical activity interventions, enhanced PE, and schooltime physical activity, such as physically active lessons. Generally, interventions focused on providing students with information about the benefits of physical activity and healthy nutrition, the risks associated with inactivity and unhealthy food choices, and the importance of increasing the amount of time students were engaged in MVPA during the school day, as well as ensuring that they expend greater amounts of energy during physical activity sessions. Interventions targeted the school curriculum (related to PE classes specifically and to the whole curriculum generally), teacher training, educational materials, changes in the format of the school day, and accessibility to exercise equipment. Interventions included training sessions for teachers (to learn more effective ways to promote physical activity and to incorporate it into curricula) and training materials including kits, packages of materials to be used in curricula, and materials to be given to students and parents. Packages included teaching notes on exercise, how the body works, and healthy eating and nutrition. Interventions also targeted PE classes by increasing the level of activity students engaged in during these classes, introducing activities geared to the age and level of development of the child, and putting greater emphasis on games. Students were encouraged to be more active outside of school during leisure time. The curriculum focused on creating a positive self‐image through awareness of physical activity benefits. Curriculum changes were implemented in other courses as well, such as science courses, which incorporated discussions of healthy eating and physical activity. Some interventions included changes in the food provided in school cafeterias, so as to increase the number of healthy food choices. Other strategies included a risk factor assessment of students to identify students with established risk factors and development of a plan to reduce student risk through increased physical activity, healthy nutrition, and goal attainment.

How the intervention might work

Given that school‐aged children spend a significant amount of their wakeful time in transit to or in the school setting, and that almost all children in many countries attend school until they reach adolescence, school‐based physical activity promotion interventions have the potential to reduce population‐wide chronic disease (Macnab 2014). In fact, several published systematic reviews have highlighted the benefits of physical activity among healthy children (Brown 2009; Cesa 2014; Granger 2017; Janssen 2010; Kriemler 2011a; Marker 2016; Poitras 2016). School‐based interventions can target simultaneously children at risk and children not at risk for future chronic disease and can increase both knowledge and behaviour conducive to healthier lifestyles. School‐based strategies targeting all students through curriculum ensure that 100% of students are exposed to the intervention, thereby increasing the reach of these interventions. Increased physical activity is an essential public health and health promotion strategy to improve child health (WHO 2008).

The intent of school‐based physical activity interventions is to increase the overall percentage of children and adolescents engaged in MVPA each day while increasing the duration of MVPA engaged in on a weekly basis. The aim of these interventions is to create a school environment that is conducive to achieving a greater proportion of children and adolescents who meet physical activity guidelines, while increasing time spent engaged in MVPA. Generally, this means that significant changes to the school curriculum are needed to support increased time for physical activity as well as increased levels of activity during this time. School‐based interventions offer an important opportunity to improve knowledge of how to prevent non‐communicable disease, and to provide both knowledge about the importance of physical activity and the opportunity for students to be more active before, during, and after school hours, thereby helping them develop healthier behaviours that may track into adulthood (Hayes 2019).

Why it is important to do this review

This systematic review was first published in 2009, with an update provided in 2013. Although the benefits of physical activity for healthy children have been documented, at the time the original review was conducted no other reviews had systematically examined the effectiveness of various combinations of school‐based interventions in promoting physical activity and fitness among children. Since that time, several new trials have been published (and are included in this update) and methodological advances have been made (e.g. using accelerometers rather than relying on self‐report data). The purpose of this update is to synthesise new data on the effectiveness of school‐based physical activity interventions with data included in the original review. This update includes evaluations of published studies indexed up to and including 1 June 2020.

Given that school‐aged children spend a significant amount of time in the school setting, and that many barriers prevent participation in physical activity outside of the school setting (e.g. resources, availability, cost), it is particularly important to understand the extent to which school‐based physical activity promotion interventions are effective in increasing activity and improving fitness levels. It is important to evaluate how these types of interventions may impact (positively or negatively) students' overall well‐being and health‐related quality of life and to discern any potential adverse events or harms. When school‐based interventions are combined with broader community‐based interventions, it is difficult to ascertain the impact of school‐based strategies. However, in developing comprehensive physical activity or chronic disease prevention strategies, it is crucial to incorporate effective school‐based strategies. Therefore, it is timely, given low worldwide participation in regular physical activity, that a review focused solely on the effectiveness of school‐based physical activity interventions be conducted and regularly updated.

Objectives

The purpose of this review update is to summarise the evidence on effectiveness of school‐based interventions in increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity and improving fitness among children and adolescents 6 to 18 years of age.

Specific objectives are:

to evaluate the effects of school‐based interventions on increasing physical activity and improving fitness among children and adolescents;

to evaluate the effects of school‐based interventions on improving body composition; and

to determine whether certain combinations or components (or both) of school‐based interventions are more effective than others in promoting physical activity and fitness in this target population.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

In accordance with the last update, we included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or cluster‐RCTs with a minimum intervention duration of 12 weeks. There are four unique departures from the protocol of this update in comparison to the original review.

Due to growing availability and use of technology‐based assessments of physical activity and sedentary time via accelerometers, and known limitations of self‐report physical activity data for children in particular, we limited this review to studies that included a device‐based measure of physical activity or sedentary time (e.g. with accelerometers). This resulted in exclusion of measures related to TV watching time from the review, replaced by overall measures of sedentary time. This change in inclusion criteria resulted in exclusion from this update of several studies that included only self‐report measures that were included in the original review.

Studies not primarily aimed at increasing levels of physical activity were excluded from this update. This resulted in exclusion of some studies that were primarily focused on nutrition or reducing/preventing obesity.

Outcomes of blood pressure and pulse rate were excluded from this update. Again, this resulted in exclusion of a very small number of studies that included only these outcomes.

For included studies, we extracted outcomes related to health‐related quality of life and adverse events when reported. This did not result in any change to inclusion or exclusion criteria.

The review authors are aware that post hoc questions are susceptible to bias (Higgins 2011); however, in light of the growing body of literature on the effectiveness of school‐based physical activity promotion interventions, we believe the changes in inclusion and exclusion criteria were necessary to ensure inclusion in this update of the most rigorous evidence related to the research question.

Types of participants

Studies that included school‐attending children and adolescents between the ages of 6 and 18 years were included in this review. This included all otherwise healthy children and adolescents, whether they were overweight or obese, or were not. We excluded studies in which participants received a physical activity intervention as part of a treatment regimen for a specific critical illness or comorbidity (e.g. diabetes). Study participants were categorised as children (age 6 to < 12) or adolescents (age 12 to 18) based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention categories (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021).

Types of interventions

Interventions

We included any school‐based physical activity programme that aimed to increase physical activity and/or fitness among children and adolescents. We defined school‐based physical activity programmes as any that implemented educational, health promotion, counselling, and/or management strategies focused on promotion of physical activity and/or fitness. The range of interventions included changes to school curriculum, training for teachers about incorporating physical activity into school curriculum and routines, and educational materials for teachers, students, and parents. In some instances, the intervention included strategies to engage parents in the intervention, as well as community‐based strategies, mass media, policy development, and environmental changes. We included studies for which interventions were targeted primarily within the school setting. In some instances, interventions were implemented in the community and in the home, in addition to school‐based interventions, although the primary focus needed to be the school setting. Included studies must have fallen within public health practice (meaning the focus was on health promotion from an individual or population‐wide perspective and was not physician or clinic based) and must have been able to be implemented, facilitated, or promoted by staff in local public health units or by public health professionals.

Comparators

The comparison could be no intervention, usual care, or a concomitant intervention. Concomitant interventions had to be the same in both intervention and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

Minimum duration of intervention

The minimum duration of follow‐up was 12 weeks. Given the abundance of literature, this criterion was added during the last update to focus on interventions that were most likely to result in meaningful and sustainable changes in the school setting (Dobbins 2013). We extracted data on extended follow‐up periods. We defined extended follow‐up periods as follow‐up of participants that occurred once the original trial, as specified in the trial protocol, had been terminated (Buch 2011; Megan 2012).

Summary of specific exclusion criteria

We excluded studies in which participants received a physical activity intervention as part of a treatment regimen for a specific critical illness or comorbidity (e.g. diabetes), studies in which the intervention was conducted entirely outside the school setting (e.g. community setting, public place, recreation facility, physician office, camp setting), and studies in which the intervention could be delivered only by a specific health professional (e.g. physician) or fitness expert.

Types of outcome measures

To be included, studies had to report one or more of the following outcomes, presented as post‐intervention measurement and standard deviation or confidence intervals, or as change from baseline with standard deviation or confidence intervals.

Primary outcomes

Proportion of students meeting recommendations for moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA)

Duration of MVPA

Sedentary time

Secondary outcomes

Physical fitness

Body mass index (BMI)

Health‐related quality of life

Adverse events

Method and timing of outcome measurement

Outcomes were primarily measured at baseline and immediately post intervention. In a small subset of studies, outcomes were measured at 6 months, at 9 months, and at 12 months, and in one study, up to 4 years post intervention.

MVPA: assessed by accelerometers during school time or non‐school (or both) time. The proportion of students who met physical activity guidelines was presented as reported or calculated by dividing the number of students engaged in 60 minutes/d of MVPA by the total number of students allocated to either the intervention group or the control group; duration of physical activity was measured as total minutes per day or weeks spent engaged in MVPA.

Sedentary time: measured as time spent sedentary in total minutes or hours per day or per week, measured via accelerometers.

BMI (kg/m²or BMI z‐score): measured by trained health professionals using calibrated scales; however, differences existed across studies in terms of which clothes were worn by participants during measurement and whether height and weight were measured during school time.

Physical fitness: measured in different ways by trained professionals. In some instances, actual maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) was measured; in many, a field‐based test such as a shuttle run or a step test was used to estimate VO₂max.

Health‐related quality of life: quantified with a validated instrument (e.g. Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory). Assessments completed by both students and parent proxies were eligible.

Adverse events: any as reported by study authors were noted, as were specific statements of no adverse events occurring.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The search for this update was conducted from the date of our last search (October 2011) to 1 June 2020. Some minor changes were made to the search strategy, such as using validated search filters for RCTs that were not available at the time of our last search and adding terms for sedentary time. Validated search filters were used within MEDLINE Ovid (Lefebvre 2019), Embase Ovid (Glanville 2019a), and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Glanville 2019b). We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library.

MEDLINE Ovid.

Embase Ovid.

CINAHL EBSCO.

PsycINFO Ovid.

BIOSIS Web of Science.

SPORTDiscus EBSCO.

Sociological Abstracts ProQuest.

For detailed search strategies, see Appendix 1. We placed no restrictions on language of publication when searching electronic databases or reviewing reference lists of identified trials.

Searching other resources

We tried to identify other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications, including trial registries, by handsearching the reference lists of all included trials and relevant systematic reviews and meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports that were identified in our search. We contacted authors of included trials to request additional information on retrieved trials and to determine if further trials exist, which we may have missed.

We did not use abstracts or conference proceedings for data extraction because this information source does not fulfil the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) requirements, which call for "an evidence‐based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomised trials" (CONSORT 2018 Scherer 2007). However, we specified trial details in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table, and we contacted study authors to determine whether further publications exist.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

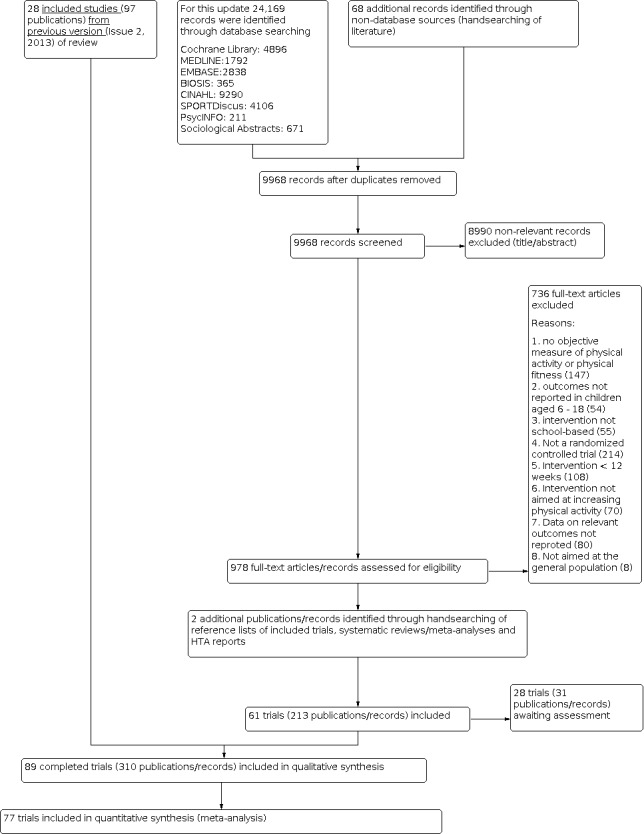

For this update, two review authors (SNS, HC) independently screened abstract, title, or both, for every record retrieved in the literature searches, to determine which trials should be assessed further. We obtained the full text of all potentially relevant records. We resolved disagreements through consensus or by recourse to a third review author (MD). If we could not resolve a disagreement, we categorised the trial as a 'study awaiting classification' and contacted trial authors for clarification. We prepared an adapted PRISMA flow diagram to show the process of trial selection (Figure 1) (Liberati 2009). We listed all articles excluded after full‐text assessment in the Characteristics of excluded studies table and provided reasons for exclusion.

1.

Trial flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

For trials that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, two review authors (SNS, HC) independently extracted key participant and intervention characteristics. We reported data on efficacy outcomes and adverse events using standardised data extraction sheets. We resolved disagreements by discussion, or, if required, we consulted a third review author (MD) (for details, see Characteristics of included studies; Table 2; Appendix 2; Appendix 3). We provided information including trial identifiers for potentially relevant ongoing trials in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

1. Overview of study populations.

| Trial ID (design) | Interventions and comparators | Screened/eligible (N) | Randomised (N) | Finishing trial (N) | Randomised finishing trial (%) |

| Breheny 2020 | I: Daily Mile | —/— | 1153 | 1107 | 96.0 |

| C: usual school routine | 1127 | 1070 | 94.9 | ||

| total: | 2280 | 2177 | 95.5 | ||

| Ketelhut 2020 | I: high‐intensity interval training during PE | —/— | — | 22 | — |

| C: usual PE | 24 | ||||

| total: | — | 46 | |||

| — | |||||

| Belton 2019 (cluster‐RCT) | I: multi‐component PE, whole‐school and parent‐targeted intervention | 564/534 | 275 | 123 | 44.7 |

| C: usual care | 259 | 126 | 48.6 | ||

| total: | 534 | 249 | 46.6 | ||

| Corepal 2019 (cluster‐RCT) | I: pedometer challenge | —/— | 142 | 136 | 95.8 |

| C: usual school | 82 | 81 | 98.8 | ||

| total: | 224 | 217 | 96.9 | ||

| Ickovics 2019 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: PA school wellness policy | —/756 | 413 | 330 | 79.9 |

| I2: PA + nutrition school wellness policy | |||||

| C1: nutrition school wellness policy | 305 | 265 | 86.9 | ||

| C2: delayed control | |||||

| total: | 718 | 595 | 82.9 | ||

| Jago 2019 (cluster‐RCT) | I: Action 3:30R after‐school PA club | 1139/1125 | 170 | 113 | 66.5 |

| C: — | 165 | 139 | 84.2 | ||

| total: | 335 | 252 | 75.2 | ||

| Leahy 2019 (cluster‐RCT) | I: Burn2Learn, multi‐component high‐intensity interval training | —/68 | 38 | 32 | 84.2 |

| C: usual school activities | 30 | 29 | 96.7 | ||

| total: | 68 | 61 | 89.7 | ||

| Lonsdale 2019a (cluster‐RCT) | I: teacher PE training | —/1806 | 693 | 630 | 90.9 |

| C: standard teaching | 728 | 628 | 86.3 | ||

| total: | 1421 | 1258 | 88.5 | ||

| Müller 2019 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: PA only | 1009/944 | — | 265 | — |

| I2: PA + health education | |||||

| I3: PA + health education + nutrition | |||||

| C1: health education + nutrition | — | 398 | — | ||

| C2: no PA | |||||

| total: | 944 | 663 | 70.2 | ||

| Ordóñez Dios 2019 | I: 2 x 45‐minute PE sessions per week and daily run | —/— | — | 45 | — |

| C: 2 x 45‐minute PE sessions per week | — | 44 | — | ||

| total: | — | 89 | — | ||

| Seibert 2019 | I: 4 core strategies to increase PA | —/— | 2495 | — | — |

| C: usual PE | 2399 | — | — | ||

| total: | 4894 | — | — | ||

|

Seljebotn 2019

(cluster‐RCT) |

I: physically active lessons, active homework, physically active recess | —/473 | 228 | 224 | 98.2 |

| C: continued normal routine, approximately 135 minutes/week of PA | 219 | 218 | 99.5 | ||

| total: | 447 | 442 | 98.9 | ||

| Zhou 2019 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: modified PE | —/— | 204 | 163 | 79.9 |

| I2: after school PA programme | 200 | 180 | 90.0 | ||

| I3: modified PE and after school PA programme | 178 | 168 | 94.4 | ||

| C: regular PE | 176 | 170 | 96.6 | ||

| total: | 758 | 681 | 89.8 | ||

| Adab 2018 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 30 minutes of additional MVPA on each school day, cooking workshops, a 6‐week healthy eating programme, information sheets for families | —/— | 1134 | 660 | 58.2 |

| C: ongoing Year 2 health‐related activities and education resources, excluding topics related to healthy eating and PA | 1328 | 732 | 55.1 | ||

| total: | 2462 | 1392 | 56.5 | ||

| Carlin 2018 (cluster‐RCT) | I: brisk walking intervention | —/— | 101 | 100 | 99.0 |

| C: continued with normal PA habits | 98 | 97 | 99.0 | ||

| total: | 199 | 197 | 99.0 | ||

| Harrington 2018 (cluster‐RCT) | I: support for PA, PE, and school sport culture and practices with support of the Youth Sport Trust and a hub school | —/1753 | 867 | 735 | 84.8 |

| C: usual practice of PE and sport | 885 | 626 | 70.7 | ||

| total: | 1752 | 1361 | 77.7 | ||

| Have 2018 (cluster‐RCT) | I: active math lessons | —/557 | 294 | 268 | 91.2 |

| C: regular classroom instruction | 211 | 182 | 86.3 | ||

| total: | 505 | 450 | 89.1 | ||

| Pablos 2018 (cluster‐RCT) | I: lunchtime extracurricular PA | —/210 | 100 | 82 | 82.0 |

| C: continued with daily activities | 90 | 76 | 84.4 | ||

| total: | 190 | 158 | 83.2 | ||

| Robbins 2018 (cluster‐RCT) | I: an after school PA club, counselling, interactive Internet‐based sessions | 4192/1543 | 766 | 706 | 92.2 |

| C: no additional after school programming | 777 | 680 | 87.5 | ||

| total: | 1543 | 1386 | 89.8 | ||

| Siegrist 2018 (cluster‐RCT) | I: weekly lifestyle lessons | 792/— | 331 | 243 | 73.4 |

| C: usual activities | 257 | 191 | 74.3 | ||

| total: | 588 | 434 | 73.8 | ||

| Ten Hoor 2018 (cluster‐RCT) | I: strength training and motivational interviewing | —/808 | 353 | 262 | 74.2 |

| C: usual curriculum | 342 | 246 | 71.9 | ||

| total: | 695 | 508 | 73.1 | ||

| Donnelly 2017 (cluster‐RCT) | I: Academic Achievement and Physical Activity Across the Curriculum lessons, 160 minutes/week of MVPA | —/698 | 316 | 244 | 77.2 |

| C: traditional classroom instruction and typical PE schedule | 268 | 204 | 76.1 | ||

| total: | 584 | 448 | 76.7 | ||

| Farmer 2017 (cluster‐RCT) | I: school‐specific playground action plan | —/— | 812 | 344 | 42.4 |

| C: no change to school play spaces | 851 | 325 | 38.2 | ||

| total: | 1663 | 669 | 40.2 | ||

| Sutherland 2017 (cluster‐RCT) | I: modified Supporting Children's Outcomes using Rewards, Exercise and Skills programme | —/1959 | 571 | — | — |

| C: delivered school PA practices according to the curriculum | 568 | — | — | ||

| total: | 1139 | — | — | ||

| Torbeyns 2017 (RCT) | I: cycling desks | —/— | 28 | 21 | 75.0 |

| C: no lifestyle change | 28 | 23 | 82.1 | ||

| total: | 56 | 44 | 78.6 | ||

| Daly 2016 (cluster‐RCT) | I: specialist‐taught PE intervention | —/— | 457 | 273 | 59.7 |

| C: usual PE programme | 396 | 267 | 67.4 | ||

| total: | 853 | 540 | 63.3 | ||

| de Greeff 2016 (cluster‐RCT) | I: physically active mathematics and language lessons | —/— | — | 181 | — |

| C: usual curriculum | — | 195 | — | ||

| total: | 388 | 376 | 96.9 | ||

| Drummy 2016 (cluster‐RCT) | I: teacher‐led activity break | —/150 | — | 54 | — |

| C: normal daily routine | — | 53 | — | ||

| total: | 120 | 107 | 89.2 | ||

| Jarani 2016 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: group circuit training‐based PE | —/767 | 261 | 253 | 96.9 |

| I2: games‐based PE | 251 | 243 | 96.8 | ||

| C: traditional PE school | 255 | 240 | 94.1 | ||

| total: | 767 | 736 | 96.0 | ||

| Kocken 2016 (cluster‐RCT) | I: theory and practical lessons on nutrition and PA | —/— | 615 | 367 | 59.7 |

| C: regular school programme or curriculum on nutrition and PA | 497 | 496 | 99.8 | ||

| total: | 1112 | 863 | 77.6 | ||

| Lau 2016 (RCT) | I: Xbox 260 Kinect gaming sessions after school | 152/84 | 40 | 40 | 100.0 |

| C: regular PA and PE class | 40 | 40 | 100.0 | ||

| total: | 80 | 80 | 100.0 | ||

| Resaland 2016 (cluster‐RCT) | I: physically active Norwegian, mathematics, and English lessons on the playground; PA breaks and PA homework | 1395/1202 | 620 | 593 | 95.6 |

| C: curriculum‐prescribed PE and PA | 582 | 530 | 91.1 | ||

| total: | 1202 | 1123 | 93.4 | ||

| Sutherland 2016 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 7 PA intervention strategies and 6 implementation strategies | —/1468 | 696 | 250 | 35.9 |

| C: only measurement components of the trial: regular PA and PE | 537 | 191 | 35.6 | ||

| total: | 1233 | 441 | 35.8 | ||

| Tarp 2016 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 60 minutes of PA during schooltime, PA homework | 869/855 | 215 | 194 | 90.2 |

| C: normal practice | 490 | 438 | 89.4 | ||

| total: | 705 | 632 | 89.6 | ||

| Cohen 2015 (cluster‐RCT) | I: teacher learning, PA policies, school‐community linkages | —/— | 199 | 166 | 83.4 |

| C: usual PE and school sport programmes | 261 | 217 | 83.1 | ||

| total: | 460 | 383 | 83.3 | ||

| Jago 2015 (cluster‐RCT) | I: after school dance classes | —/663 | 284 | — | — |

| C: provided data only | 287 | — | — | ||

| total: | 571 | 508 | 89.0 | ||

| Madsen 2015 (cluster‐RCT) | I: nutrition education curriculum, Playworks structured recess before or after school activities, PA and games implemented by teachers | —/— | 583 | 446 | 76.5 |

| C: — | 296 | 230 | 77.7 | ||

| total: | 879 | 676 | 76.9 | ||

| Muros 2015 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: extracurricular PA sessions | 242/162 | 28 | 28 | 100.0 |

| I2: PA and nutrition | 21 | 21 | 100.0 | ||

| I3: PA and nutrition and extra virgin olive oil during the final month | 25 | 25 | 100.0 | ||

| C1: nutrition and lifestyle education sessions | 41 | 41 | 100.0 | ||

| C2: usual activities | |||||

| total: | 135 | 135 | 100.0 | ||

| Suchert 2015 (cluster‐RCT) | I: multi‐level intervention targeting students, classrooms, schools, and parents | —/1489 | 790 | 702 | 88.9 |

| C: no intervention | 506 | 460 | 90.9 | ||

| total: | 1296 | 1162 | 89.7 | ||

| Andrade 2014 (cluster‐RCT) | I: ACTIVITAL individual‐ and environment‐based intervention | —/— | 700 | 550 | 78.6 |

| C: standard curriculum | 740 | 533 | 72.0 | ||

| total: | 1440 | 1083 | 75.2 | ||

| Jago 2014 (cluster‐RCT) | I: Action 3:30 activity club | —/— | 284 | 153 | 53.9 |

| C: schools provided data only | 255 | 157 | 61.6 | ||

| total: | 539 | 310 | 57.5 | ||

| Kipping 2014 (cluster‐RCT) | I: PA education intervention | 2242/2221 | 1064 | — | — |

| C: continued standard education provision | 1157 | — | — | ||

| total: | 2221 | 1252 | 56.4 | ||

| Kobel 2014 (cluster‐RCT) | I: teacher training, PA education, active breaks | 3159/1968 | — | — | — |

| C: no intervention | — | — | — | ||

| total: | 1964 | 1724 | 87.8 | ||

| Martinez‐Vizcaino 2014 (cluster‐RCT) | I: MOVI‐2 extracurricular PA programme | —/— | 769 | 420 | 54.6 |

| C: standard PE curriculum | 823 | 492 | 59.8 | ||

| total: | 1592 | 912 | 57.3 | ||

| Nogueira 2014 (cluster‐RCT) | I: high‐intensity capoeira sessions | 341/339 | 185 | 176 | 95.1 |

| C: usual school activities | 154 | 135 | 87.7 | ||

| total: | 339 | 138 | 40.7 | ||

| Santos 2014 (cluster‐RCT) | I: healthy buddies, healthy living lessons, structured aerobic exercise | —/— | 340 | 310 | 91.2 |

| C: standard curriculum | 347 | 273 | 78.7 | ||

| total: | 687 | 583 | 84.9 | ||

| Toftager 2014 (cluster‐RCT) | I: physical and organisational environmental changes | —/— | 623 | 551 | 88.4 |

| C: — | 725 | 608 | 83.9 | ||

| total: | 1348 | 1159 | 86.0 | ||

| Fairclough 2013 (cluster‐RCT) | I: weekly lesson plans, worksheets, homework tasks, lesson resources | 420/318 | 166 | 117 | 70.5 |

| C: normal instruction | 152 | 89 | 58.6 | ||

| total: | 318 | 196 | 61.6 | ||

| Ford 2013 (RCT) | I: accumulated brisk walking programme | —/174 | — | 77 | — |

| C: normal school lessons | — | 75 | — | ||

| total: | 174 | 152 | 87.4 | ||

| Grydeland 2013 (cluster‐RCT) | I: structured lessons, PA breaks, PA promotion | —/— | 784 | 519 | 66.2 |

| C: — | 1381 | 945 | 68.4 | ||

| total: | 2165 | 1464 | 67.6 | ||

| Melnyk 2013 (cluster‐RCT) | I: goal‐setting, education, PA homework | 1560/807 | 374 | 286 | 76.5 |

| C: Healthy Teens attention control curriculum was intended to promote knowledge of common adolescent health topics and health literacy | 433 | 341 | 78.8 | ||

| total: | 807 | 627 | 77.7 | ||

| Sacchetti 2013 (cluster‐RCT) | I: daily PA in schoolyard and classroom | 521/521 | 247 | 212 | 85.8 |

| C: standard programme of PE | 250 | 216 | 86.4 | ||

| total: | 497 | 428 | 86.1 | ||

| Siegrist 2013 (cluster‐RCT) | I: JuvenTUM educational and environmental intervention | —/902 | 486 | 427 | 87.9 |

| C: continued with usual school activities | 340 | 297 | 87.4 | ||

| total: | 826 | 724 | 87.7 | ||

| Aburto 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: basic intervention of environmental and policy‐level changes | —/— | 262 | 241 | 92.0 |

| I2: plus intervention adding additional resources and daily morning exercise | 264 | 242 | 91.7 | ||

| C: no change to standard practices | 338 | 216 | 63.9 | ||

| total: | 864 | 699 | 80.9 | ||

| Ardoy 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: 4 sessions/week of PE | 70/67 | 26 | 25 | 96.2 |

| I2: 4 sessions/week of PE with emphasis on increasing intensity | 23 | 23 | 100.0 | ||

| C: 2 sessions/week of PE | 18 | 18 | 100.0 | ||

| total: | 67 | 66 | 98.5 | ||

| de Heer 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I: Bienstar intervention of health education and 45 to 60 minutes of after school PA | 1720/901 | 292 | 242 | 82.9 |

| C1: Grade 4 health workbooks and incentives | 251 | 236 | 94.0 | ||

| C2: spillover control group | 354 | 326 | 92.1 | ||

| total: | 897 | 804 | 89.6 | ||

| Jago 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I: education, social marketing, food environment, PE curriculum, equipment provision | —/11158 | 5571 | 2060 | 37.0 |

| C: recruitment and data collection only | 5587 | 2003 | 35.9 | ||

| total: | 11158 | 4063 | 36.4 | ||

| Jansen 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 3 PE sessions/week, additional after school sport and play, classroom education, parent health promotion | —/— | 1271 | 1149 | 90.4 |

| C: continued with usual curriculum | 1499 | 1267 | 84.5 | ||

| total: | 2770 | 2416 | 87.2 | ||

| Magnusson 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I: students engaged in PA during PE lessons, during recess, and during classes; schools had access to PA equipment to use in school lessons; teaching materials promoting PA were provided | —/321 | 151 | 138 | 91.4 |

| C: followed the general PA curriculum | 170 | 116 | 68.2 | ||

| total: | 321 | 254 | 79.1 | ||

| Okely 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I: PA action plan | —/1769 | 771 | 566 | 73.4 |

| C: continuation of usual programmes | 747 | 633 | 84.7 | ||

| total: | 1518 | 1199 | 79.0 | ||

| Thivel 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 120 minutes of additional supervised PE | —/— | 229 | 229 | 100.0 |

| C: habitual 2 hours of PE/week | 228 | 228 | 100.0 | ||

| total: | 457 | 457 | 100.0 | ||

| Wilson 2011 (cluster‐RCT) | I: Active by Choice Today programme, PA homework, in‐school PA, motivational skills training | 729 | 673 | 92.3 | |

| C: General Health Education Programme | 693 | 635 | 91.6 | ||

| total: | 1422 | 1308 | 92.0 | ||

| Kriemler 2010 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 2 additional 45‐minute PE lessons/week, activity breaks, PA homework | 305 | 297 | 97.4 | |

| C: usual mandatory PE lessons | 235 | 205 | 87.2 | ||

| total: | 540 | 502 | 93.0 | ||

| Neumark‐Sztainer 2010 (cluster‐RCT) | I: New Moves curriculum (nutrition and self‐empowerment, motivational interviewing, lunch meetings, parent outreach) | 687 | 182 | 177 | 97.3 |

| C: participation in all‐girls PE class | 174 | 159 | 91.4 | ||

| total: | 356 | 336 | 94.4 | ||

| Angelopoulos 2009 (cluster‐RCT) | I: educational intervention covering self‐esteem, body image, nutrition, PA, fitness, and environmental issues, with motivational methods to increase knowledge, skills, self‐efficacy, self‐monitoring, and social influence | — | 321 | — | |

| C: — | — | 325 | — | ||

| total: | — | 646 | — | ||

| Donnelly 2009 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 90 minutes/week of moderate to vigorous physically active academic lessons | 814 | 792 | 97.3 | |

| C: regular classroom instruction | 713 | 698 | 97.9 | ||

| total: | 1527 | 1490 | 97.6 | ||

| Dorgo 2009 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: PE manual resistance training programme | 141 | 93 | 66.0 | |

| I2: PE manual resistance training plus cardiovascular endurance training | |||||

| C: regular PE programme that followed the usual school curriculum | 232 | 129 | 55.6 | ||

| total: | 373 | 222 | 59.5 | ||

| Gentile 2009 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 'Switch' programme: promoted healthy lifestyles targeting family, school, and community | 670 | — | — | |

| C: no intentional exposure to the Switch programme | 653 | — | — | ||

| total: | 1323 | 1029 | 77.8 | ||

| Neumark‐Sztainer 2009 (cluster‐RCT) | I: after school theatre sessions, booster sessions, family outreach | 56 | 51 | 91.1 | |

| C: a theatre‐based control condition | 52 | 45 | 86.5 | ||

| total: | 108 | 96 | 88.9 | ||

| Peralta 2009 (RCT) | I: curriculum and peer‐facilitated lunchtime PA session, parent newsletters | 16 | 16 | 100.0 | |

| C: PA curriculum | 17 | 16 | 94.1 | ||

| total: | 33 | 32 | 97.0 | ||

| Walther 2009 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 1 unit of physical exercise (45 minutes) with at least 15 minutes of endurance training/school day, plus lessons on healthy lifestyle once/ month | 112 | 109 | 97.3 | |

| C: German standards, 2 units (each 45 minutes) of PE/week, 12 units (45 minutes/ unit) of high‐level endurance exercise training/week plus participation in competitive sporting events | 76 | 73 | 96.1 | ||

| total: | 188 | 182 | 96.8 | ||

| Reed 2008 (cluster‐RCT) | I: Action Schools!BC whole‐school PA approach | 178 | 156 | 87.6 | |

| C: regular programme of PE and school‐based PA | 90 | 81 | 90.0 | ||

| total: | 268 | 237 | 88.4 | ||

| Salmon 2008 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 1, 2, 3 behavioural modification group; fundamental motor skills group; combined behavioural modification and fundamental motor skills group | 233 | 213 | 91.4 | |

| C: usual classroom lessons | 62 | 55 | 88.7 | ||

| total: | 295 | 268 | 90.8 | ||

| Wang 2008 (cluster‐RCT) | I: 'FitKid' after school intervention sessions | 603 | 260 | 43.1 | |

| C: — | 584 | 265 | 45.4 | ||

| total: | 1187 | 525 | 44.2 | ||

| Webber 2008 (cluster‐RCT) | I: health education lessons to enhance behavioural skills known to influence PA participation (self‐monitoring, setting goals for behaviour change) | — | — | — | |

| C: — | — | — | — | ||

| total: | 3502 | 3378 | 96.5 | ||

| Weeks 2008 (RCT) | I: directed jumping activity at the beginning of every PE class | 52 | 43 | 82.7 | |

| C: regular PE warm‐ups and stretching at the beginning of every PE class | 47 | 38 | 80.9 | ||

| total: | 99 | 81 | 81.8 | ||

| Barbeau 2007 (RCT) | I: after school PA programme | — | — | 81 | |

| C: — | — | — | 84 | ||

| total: | — | — | — | ||

| Williamson 2007 (cluster‐RCT) | I: Healthy Eating and Exercise programme to increase PA during the school day and at home | 313 | 282 | 90.1 | |

| C: Alcohol/Drug/Tobacco abuse prevention programme | 348 | 304 | 87.4 | ||

| total: | 661 | 586 | 88.7 | ||

| Haerens 2006 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: a computer‐tailored intervention to increase MVPA to 60 minutes/d, increase fruit consumption, increase water consumption, and reduce fat | 2105 | — | — | |

| I2: group 1 plus parental involvement | |||||

| C: no PA and nutrition intervention | 735 | — | — | ||

| total: | 2840 | 2434 | 85.7 | ||

| Young 2006 (RCT) | I: PE curriculum taught 5 days/week and family | 116 | 111 | 95.7 | |

| C: standard PE class | 105 | 99 | 94.3 | ||

| total: | 221 | 210 | 95.0 | ||

| Bayne‐Smith 2004 (RCT) | I: Physical Activity and Teenage Health programme, education sessions plus 20 to 25 minutes of PA | — | 310 | — | |

| C: same frequency or duration of PE classes, but without lecture or discussion | — | 132 | — | ||

| total: | — | 442 | — | ||

| Simon 2004 (cluster‐RCT) | I: an educational component focusing on PA and sedentary behaviours and new opportunities for PA during and after school hours | — | 475 | — | |

| C: — | — | 479 | — | ||

| total: | 1046 | 954 | 91.2 | ||

| Trevino 2004 (cluster‐RCT) | I: health programming regarding 3 health behaviour messages associated with diabetes mellitus control and goal‐setting | 969 | 619 | 63.9 | |

| C: — | 1024 | 602 | 58.8 | ||

| total: | 1993 | 1221 | 61.3 | ||

| Stone 2003 (cluster‐RCT) | I: food service, skills‐based classroom curricula, family, and PE | 879 | 644 | 73.3 | |

| C: — | 825 | 653 | 79.2 | ||

| total: | 1704 | 1297 | 76.1 | ||

| Burke 1998 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: standard PA and nutrition programme including classroom lessons, fitness sessions daily, and nutrition programme | — | — | — | |

| I2: I1 plus a PA enrichment programme for higher‐risk children | |||||

| C: no programme | — | — | — | ||

| total: | 800 | 720 | 90.0 | ||

| Ewart 1998 (RCT) | I: 50‐minute 'Project Heart' aerobic exercise classes | 45 | 44 | 97.8 | |

| C: 50‐minute standard PE classes | 54 | 44 | 81.5 | ||

| total: | 99 | 88 | 88.9 | ||

| Luepker 1996 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: school food service modifications, PE interventions, and Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health curricula | 3651 | 3297 | 90.3 | |

| I2: I1 plus a family‐based programme | |||||

| C: usual health curricula, PE, and food service programmes | 1455 | 722 | 49.6 | ||

| total: | 5106 | 4019 | 78.7 | ||

| Bush 1989 (cluster‐RCT) | I1: 'Know Your Body' curriculum focusing on nutrition, fitness, prevention of smoking, a personalised health screening, and results on a 'health passport' for parentsg | — | — | — | |

| I2: 'Know Your Body' curriculum and health screening, but students do not receive the results of their screening; only parents receive the results | |||||

| C: health screening only | — | — | — | ||

| total: | 892 | 431 | 48.3 | ||

| Walter 1988 (cluster‐RCT) | I: special curriculum targeting voluntary changes in risk behaviour in the areas of diet, PA, and smoking | — / 3388 | 2075 | 1104 | 53.2 |

| C: — | 1313 | 665 | 50.6 | ||

| total: | 3388 | 1769 | 52.2 | ||

| Grand total | All interventions | 46 073 | 28 089 | ||

| All comparators | 40 566 | 23 639 | |||

| All interventions and comparators b | 96 740 | 66 752 | |||

—: denotes not reported.

aFollow‐up under randomised conditions until end of trial (= duration of intervention + follow‐up post intervention or identical to duration of intervention); extended follow‐up refers to follow‐up of participants once the original trial was terminated as specified in the power calculation.

bNote that numbers from all interventions and all interventions and comparators are greater than the sum of interventions only and comparators only, as some studies reported only the total number of included participants and did not note numbers within each group.

C: comparator; I: intervention; MVPA: moderate to vigorous physical activity; NA: not applicable; PA: physical activity; PE: physical education; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

We emailed all authors of included trials to enquire whether they would be willing to answer questions regarding their trials. We thereafter sought relevant missing information on the trial from the primary trial author(s), if required.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents, or multiple reports of a primary trial, we maximised the information yield by collating all available data, and we used the most complete data set aggregated across all known publications. We listed duplicate publications, companion documents, multiple reports of a primary trial, and trial documents of included trials (such as trial registry information) as secondary references under the study identifier (ID) of the included trial. Furthermore, we listed duplicate publications, companion documents, multiple reports of a trial, and trial documents of excluded trials (such as trial registry information) as secondary references under the study ID of the excluded trial.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this review, all newly included studies were assessed independently for risk of bias by two review authors (SNS, HC) according to six domains (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting) using the ‘Risk of Bias 1’ tool in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assign assessment of low, high, or unclear risk of bias (for details, see Appendix 4) (Higgins 2017). Incomplete outcome data were rated separately for (1) device‐based measures of physical activity and sedentary time, and (2) BMI and fitness, due to the large proportion of missing data that is often seen in studies using accelerometers. For studies that used a cluster‐randomised design, four additional domains (recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, and incorrect analysis) were assessed. All disagreements were resolved through discussion. If adequate information was unavailable, trial authors were contacted to request missing data on ‘Risk of bias’ items.

Two main changes were made to the assessment of risk of bias for this update. First, due to changes to Cochrane recommendations, blinding is now assessed separately for participants and personnel, and outcome assessors. Previously included studies were re‐assessed for this domain. In this update, we do not include assessment for control for confounders or reliability and validity of data collection methods. Second, previously included studies that utilised a cluster‐randomised design were appraised for the four new cluster‐randomised trial domains. Finally, assessment of 'other' risk of bias has been removed.

Risk of bias for an outcome across trials and across domains

These are the main summary assessments that we incorporated into our judgements about quality of evidence in Table 1. We defined outcomes as at low risk of bias when most weight in the meta‐analysis comes from trials at low risk of bias, unclear risk when most weight in the meta‐analysis comes from trials at low or unclear risk of bias, and high risk when a sufficient proportion of information comes from trials at high risk of bias. We defined single studies as having low risk of bias when all but one domain was assessed to be at low risk of bias, or when all but two domains were assessed at low risk of bias, one of which was 'blinding of participants and personnel', as adequate blinding of study participants is nearly impossible to do well in school‐based physical activity interventions. We defined single studies to be at high risk of bias when at least three domains were assessed as having unclear or high risk of bias, or when four domains were assessed as having unclear or high risk of bias, one of which was 'blinding of participants and personnel'.

Measures of treatment effect

When at least five included trials were available for comparison of a given outcome measured on the same scale (e.g. MVPA in minutes/d), we combined effects into a meta‐analysis. When available, we extracted data on post‐intervention values adjusted for baseline differences, along with confidence intervals or standard deviation. When only changes from baseline were reported, these differences, along with confidence intervals or standard deviations, were extracted. Both were combined in meta‐analyses, with the calculator function in RevMan 5.4 used to calculate adjusted between‐group difference, as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2021).

When possible, we combined multiple study groups into a single pairwise comparison using formulae for combining continuous data from multiple groups as provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions when separate data were presented for each group, or when between‐group comparisons from multiple group had independent control groups (e.g. when results were presented separately for boys and girls or by grade level) (Higgins 2017). When between‐group differences were reported between multiple intervention groups and the same control group, we did not include these data in the meta‐analysis, so as not to double‐count participants in control groups.

Unit of analysis issues

We considered the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome. If more than one comparison from the same trial was eligible for inclusion in the same meta‐analysis, we used the end of intervention comparison.

Standard errors for cluster‐RCTs that were not appropriately adjusted for potential clustering of participants within clusters in analyses were adjusted using the design effect (1 + (M‐1) × ICC), where M is the average cluster size, and ICC is the intraclass correlation coefficient (Higgins 2017). The ICC was estimated at 0.01, as has been previously reported (Murray 2006).

Dealing with missing data

If possible, we obtained missing data from authors of included trials. We carefully evaluated important numerical data such as screened, randomly assigned participants, as well as intention‐to‐treat and as‐treated and per‐protocol populations. We investigated attrition rates (e.g. dropouts, losses to follow‐up, withdrawals), and we critically appraised issues concerning missing data and use of imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward). When included trials did not report sufficient data for inclusion in the meta‐analysis (e.g. provided only P values) and we did not receive requested information from trial authors, we did not include these studies in the meta‐analysis; however, we included them in the narrative tables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We identified heterogeneity (inconsistency) by visually inspecting forest plots and by using a standard Chi² test with a significance level of α = 0.1 (Deeks 2021). In view of the low power of this test, we also considered the I² statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across trials to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003). When we found heterogeneity, we attempted to determine possible reasons for this by examining individual trial and subgroup characteristics in the narrative summary.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we included 10 or more trials that investigated a particular outcome, we planned to use funnel plots to assess small‐trial effects. Several explanations may account for funnel plot asymmetry, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to trial size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small trials), and publication bias (Sterne 2017).

Data synthesis

We planned to undertake (or display) a meta‐analysis only if we judged participants, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes to be sufficiently similar to ensure an answer that is clinically meaningful. We used random‐effects meta‐analyses to calculate the mean of the effects of included studies (Borenstein 2017a; Borenstein 2017b; Higgins 2009). We performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2021).

When studies could not be included in the meta‐analysis, for example, because they did not report the required data or they measured the outcome in a format that was incompatible with other studies, we summarised results from each study under Results and in table form. We used vote counting based on the direction of effect to determine whether the majority of studies found a positive or negative effect (McKenzie 2021).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Given the differences between children and adolescents with respect to school setting, types of interventions, etc., we explored the effects of interventions on these two age groups separately, using the subgroup function in Review Manager 5.4.

Given the substantial heterogeneity in types of interventions included, we conducted secondary analyses to synthesise results with respect to each outcome type by subcategories of intervention types. For this purpose, we broadly categorised each intervention type as primarily focused on (1) before or after school physical activity programmes, for example, after school dance clubs, walk to school programmes; (2) enhanced PE classes that focused on increasing the frequency, duration, intensity, or types of activities above and beyond the usual PE classes; (3) multi‐component interventions that typically included a whole‐school approach and utilised multiple strategies including environmental changes to increase physical activity, and often promoted healthy eating or healthy weight amongst students; and (4) schooltime physical activity interventions, such as active academic lessons or cycling desk interventions that focused on integrating physical activity throughout the school day itself rather than restricting physical activity to recess or PE classes.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed no sensitivity analyses.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to assess overall certainty of evidence for each of the primary and secondary outcome measures. GRADE takes into account issues related to both internal and external validity to state how confident we are in the effect estimates presented. Two review authors (SNS, HC) independently rated the certainty of evidence for each outcome. We resolved differences in assessment by discussion. For each outcome, we rated evidence certainty as very low, low, moderate, or high based on the GRADE domains as described in Chapter 14 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2021). As only RCTs were included, the starting point for certainty of evidence was high. Then we considered each GRADE domain to determine whether downgrading of certainty was needed based on:

risk of bias ‐ based on critical appraisal using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool;

inconsistency of results ‐ based on visual inspection of forest plots and I² in meta‐analyses and consistency of effects reported across narrative syntheses;

indirectness ‐ based on the validity of outcome measures used and how directly they measured the outcome of interest, for example, studies that measure VO₂ peak as a direct measure of fitness provide greater certainty than studies that report estimated fitness based on functional tests;

publication bias ‐ based on a small number of studies or indication of publication bias based on funnel plots; and

imprecision ‐ based on width of the confidence intervals, and whether they include the possibility of a small or null effect.

We presented a summary of the evidence in Table 1. This provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of effect as absolute differences for each relevant comparison, numbers of participants and trials addressing each important outcome, and a rating of overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the 'Summary of findings' table using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2021), along with Review Manager (RevMan 5.4) table editor (RevMan 2014). We reported the following outcomes, listed according to priority.

MVPA (proportion meeting guidelines, duration).

Sedentary time.

Physical fitness.

BMI.

Health‐related quality of life.

Adverse events.

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of trials, see Table 2, Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies sections.

Results of the search

A total of 16,219 records related to physical activity interventions with children and adolescents were identified for the last update. Of these, 587 studies were assessed for eligibility, and 44 were deemed to meet the criteria for inclusion in the review. The most common reasons studies were judged as not relevant were data on relevant outcomes not reported, studies not RCTs, and studies not relevant to public health.

For this update, when the new inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (i.e. only studies in which the primary aim was to increase levels of physical activity and that included an objective measure of physical activity, physical fitness, or body composition), 16 of the original 44 studies were excluded: 11 included only self‐report measures (Araujo‐Soares 2009a; Colin‐Ramirez 2010; Dishman 2004; Haerens 2006; Jones 2008; Kipping 2008; Lubans 2009; McManus 2008; Petchers 1988; Singhal 2010; Verstraete 2006); three did not include any measure of physical activity or physical fitness (Li 2010; Martinez 2008; Stephens 1998); and two did not have a primary objective to increase physical activity (Robinson 1999; Singh 2009). Therefore, this update includes 28 of the 44 studies included in the last update (Angelopoulos 2009; Barbeau 2007; Bayne‐Smith 2004; Burke 1998; Bush 1989; Donnelly 2009; Dorgo 2009; Ewart 1998; Gentile 2009; Haerens 2006; Kriemler 2010; Luepker 1996; Neumark‐Sztainer 2009; Neumark‐Sztainer 2010; Peralta 2009; Reed 2008; Salmon 2008; Simon 2004; Stone 2003; Trevino 2004; Walter 1988; Walther 2009; Wang 2008; Webber 2008; Weeks 2008; Williamson 2007; Wilson 2011; Young 2006).

The search strategy for this update from October 2011 to June 2020 yielded 9968 records. Of these, 978 unique full texts were assessed for eligibility. A total of 61 studies met all relevance criteria and were included in this update (Aburto 2011; Adab 2018; Andrade 2014; Ardoy 2011; Belton 2019; Breheny 2020; Carlin 2018; Cohen 2015; Corepal 2019; Daly 2016; de Greeff 2016; de Heer 2011; Donnelly 2017; Drummy 2016; Fairclough 2013; Farmer 2017; Ford 2013; Grydeland 2013; Harrington 2018; Have 2018; Ickovics 2019; Jago 2011; Jago 2014; Jago 2015; Jago 2019; Jansen 2011; Jarani 2016; Ketelhut 2020; Kipping 2014; Kobel 2014; Kocken 2016; Lau 2016; Leahy 2019; Lonsdale 2019a; Madsen 2015; Magnusson 2011; Martinez‐Vizcaino 2014; Melnyk 2013; Müller 2019; Muros 2015; Nogueira 2014; Okely 2011; Ordóñez Dios 2019; Pablos 2018; Resaland 2016; Robbins 2018; Sacchetti 2013; Santos 2014; Seibert 2019; Seljebotn 2019; Siegrist 2013; Siegrist 2018; Suchert 2015; Sutherland 2016; Sutherland 2017; Tarp 2016; Ten Hoor 2018; Thivel 2011; Toftager 2014; Torbeyns 2017; Zhou 2019). The most common reasons studies were judged as not relevant were (1) studies were not RCTs; (2) no device‐based measure of physical activity or physical fitness was included; and (3) the intervention lasted < 12 weeks. This update includes 89 studies (28 from the last review and 61 from this update). A flow diagram depicting these results is presented in Figure 1.

A total of 84 authors were contacted for missing information, and 126 responses were received (median 1 response, range 0 to 4). In most cases, study authors were able to provide clarification on risk of bias or study characteristics, but few of them provided updated outcome data.

Included studies

In addition to information included in the Characteristics of included studies table, we have presented greater detail for each study in Table 2 (overview of study populations) and in Appendix 2 (baseline characteristics). The following is a succinct overview.

Trial design