Abstract

Previous research on culture and emotion regulation has focused primarily on comparing participants from individualistic and collectivistic backgrounds (e.g., European Americans vs. Asians/Asian Americans). However, ethnic groups that are equally individualistic or collectivistic can still vary notably in cultural norms and practices regarding emotion regulation. The present study examined the association between expressive suppression and well-being in two collectivistic ethnic groups (i.e., Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans). Results indicated that suppression of positive emotions was related to lower hedonic and eudaimonic well-being among Mexican Americans but not among Chinese Americans. Moreover, post hoc analysis revealed that Mexican Americans with a stronger collective identity reported lower eudaimonic well-being when suppressing positive emotions than Mexican Americans with a weaker collective identity. Suppression of negative emotions, by contrast, was unrelated to hedonic and eudaimonic well-being for both ethnic groups. Overall, our findings underscore the importance of taking into account the role that culture and the characteristics of emotion (e.g., valence) may play in the link between emotion regulation and well-being.

Keywords: culture, expressive suppression, well-being, Chinese Americans, Mexican Americans

There is an abundance of empirical data linking expressive suppression (i.e., the inhibition of the outward expressive manifestation of emotional experiences; Gross, 1998) to negative psychological outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and lower life satisfaction (Gross & John, 2003; Gross & Levenson, 1997). However, evidence from several recent studies suggests that the negative impact of suppression on psychological outcomes may be weaker or less prevalent in collectivistic than individualistic cultural contexts (Cheung & Park, 2010; Soto, Perez, Kim, Lee, & Minnick, 2011; Su, Lee, & Oishi, 2013). For example, Cheung and Park (2010) found a weaker association between anger suppression and self-reported depressive symptoms among Asian American college students than their European American counterparts. Because most cross-cultural studies involving collectivistic cultural groups have focused on Asians and Asian Americans, it is unknown whether the link between suppression and psychological functioning is similar among other collectivistic cultural groups, such as Mexican Americans.

Prior research has also tended to focus on suppression, broadly speaking, without determining how suppression and its associated outcomes might vary depending on the type of emotions expressed (for exceptions, see Gross, Richards, & John, 2006; Su et al., 2013; Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, Freire-Bebeau, & Przymus, 2002). Specifically, the differentiation between positive and negative emotions has rarely been the focus of cross-cultural research on suppression and its link to psychological outcomes. Positive emotions (e.g., happiness, contentment, or excitement) and negative emotions (e.g., fear, anger, or sadness) denote feeling states that tend to be evaluated as psychologically pleasant or unpleasant, respectively (Watson & Tellegen, 1985; Westbrook, 1976). Some cultures encourage the suppression of both positive and negative emotions, whereas others are concerned primarily with the suppression of negative emotions. These culture-specific norms and practices may, in turn, determine the outcome associated with suppression (Consedine, Magai, & Bonanno, 2002). For example, previous findings indicate that Asian Americans tend to suppress positive emotions more than European Americans (Gross et al., 2006; Tsai et al., 2002). Greater opportunities to practice this type of suppression, in turn, make it easier for Asian Americans to suppress positive emotions spontaneously compared with European Americans, who tend to use it less regularly in daily life (Gross et al., 2006).

Suppression in Collectivistic Cultural Contexts

Most cross-cultural studies have focused on suppression and its psychological consequences among Asians/Asian Americans and European Americans, who are often used as the prototypical representatives of collectivistic and individualistic cultural groups, respectively. Theoretical arguments have been advanced for why suppression might vary across these groups. For example, suppression of emotions is generally considered maladaptive in individualistic cultural contexts (where the personal needs of the individual are given priority over group allegiances and obligations; Hofstede, 2001) because this emotion regulation strategy tends to discourage individualistically-oriented behaviors such as self-assertion and authenticity (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In contrast, suppression may be more valued in collectivistic cultural contexts (where the needs of one’s group is valued over one’s own personal needs; Bedford & Hwang, 2003) because this emotion regulation strategy is helpful for achieving social harmony and other group goals (Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Wierzbicka, 1994).

Despite the contributions of past research, an exclusive focus on differences in the consequences of suppression between Asians/Asian Americans and European Americans is likely to impede knowledge about individuals who fall outside of these two broad cultural groups. For instance, research focused on Asian culture as the lone exemplar of a collectivist context may overlook the potential for important differences among collectivistic cultures that may influence the use of suppression and its outcomes. Although some studies have included multiple groups in their studies (e.g., Gross & John, 2003), few have examined variation within two collectivistic ethnic groups (for an exception, see Soto, Levenson, & Ebling, 2005). To address this issue, we conducted a study comparing suppression and its association with well-being among Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans, both of whom have been characterized as collectivistic (Soto et al., 2005).

Chinese Americans and Emotion

Discourse regarding the value of emotional restraint can be found in many influential sources of Chinese cultural traditions, including Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism (Hwang & Chang, 2009; Li & Jia, 2004). Confucian philosophy, for example, views emotional self-control as essential for achieving important life goals such as self-cultivation and the maintenance of social harmony (Chen & Swartzman, 2001). Traditionally, Chinese families tend to promote emotional restraint in their children (Bond & Hwang, 1986; Wu, 1996). Chinese emotional reactions during parent–child interactions have been described as inhibited and infrequent (Chen et al., 1998; Lin & Fu, 1990).

As a result of differences in emotion-related norms and practices, it is not surprising that compared with many ethnic groups, the Chinese, in general, tend to control the expression of their emotions. For example, Chinese Americans have been found to report less intense emotions during emotion-eliciting tasks compared with Mexican Americans (Soto et al., 2005) and European Americans (Tsai & Levenson, 1997). Compared with European Americans, Chinese and Asian Americans tend to report both greater suppression of emotions in general (Cheung & Park, 2010; Gross & John, 2003; Soto et al., 2011), and greater suppression of positive emotions in particular (Gross et al., 2006; Tsai & Levenson, 1997).

Within the Chinese cultural context, the observed association between suppression and negative outcomes has been fairly weak. A recent study by Soto and colleagues (2011) found that suppression was unrelated to life satisfaction and depressive symptomolgy among Hong Kong Chinese. These results were corroborated by another cross-national study that showed no association between suppression of positive emotions and psychological functioning among Chinese in Singapore (Su et al., 2013). Findings from other studies also indicate that suppression of negative emotions is weakly related to negative outcomes among Asian Americans (Cheung & Park, 2010) and those holding Asian cultural values (Butler, Lee, & Gross, 2007). Nonetheless, one major issue concerns whether the patterns observed among Chinese and individuals from other Asian ethnic groups can be generalized to other collectivistic ethnic groups, such as Mexican Americans.

Mexican Americans and Emotion

Mexican and other Latino Americans have generally been found to endorse collectivistic attitudes to a greater extent compared with European Americans (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002; Shkodriani & Gibbons, 1995; Triandis, Marín, Lisansky, & Betancourt, 1984). According to Mexican cultural norms and values, great emphasis is placed on being agreeable and emotionally responsive in order to promote interpersonal harmony and cohesion. The Latino cultural value of simpatia creates normative expectations among Mexicans and other Latinos to foster and maintain positive social relationships through the expression of positive emotions and the downplaying of negative emotions (Ramírez-Esparza, Gosling, & Pennebaker, 2008; Triandis et al., 1984). In contrast to the Chinese, who are socialized to suppress emotions in general (i.e., both positive and negative emotions), there is normative expectation within Mexican American communities to suppress negative emotions but to express positive emotions for the sake of group harmony. This cultural difference is consistent with a recent study showing that Mexicans tend to value expressive, high-arousal positive emotions (e.g., excitement or delight) than controlled, low-arousal positive emotions (e.g., calmness or serenity); the opposite pattern was observed among Chinese and other East Asians (Ruby, Falk, Heine, Villa, & Silberstein, 2012). However, the theorized patterns for Mexicans with respect to the suppression of negative versus positive emotions have not been empirically documented, precluding definitive conclusions regarding the link between suppression and psychological functioning among individuals of Mexican descent.

Investigations into the link between suppression and psychological well-being among Mexican Americans would be highly relevant and important for understanding factors that play important roles in the psychological functioning of individuals who belong to this ethnic group. Because the expression of positive emotions is highly valued in Mexican culture, individuals who fail to meet this cultural expectation may be prone to experiencing negative mental health consequences, such as low psychological well-being. If that is the case, then chronic suppression of positive emotions may serve as a psychological risk factor for Mexican Americans.

The Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to compare Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans on the relation between suppression and psychological well-being. Current conceptualizations of psychological well-being mostly fall under two broad traditions of research: the hedonic approach and the eudaimonic approach. Evidence from past research indicates that hedonic and eudaimonic well-being are related, and yet distinct, types of experience (for review, see Ryan & Deci, 2001). Hedonic well-being refers to the extent to which a person experiences subjective pleasure or happiness. It focuses on individuals’ affective and cognitive appraisals of their life experiences, and includes life satisfaction as a primary index of well-being (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999). By contrast, eudaimonic well-being refers to the extent to which a person is living in accordance with his or her true nature (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Eudaimonic well-being taps into individuals’ experiences of purpose, growth, and personally enriching activities that may or may not be accompanied by pleasant feelings (Ryff & Singer, 1998, 2000). According to the eudaimonic perspective, well-being cannot be equated with subjective pleasure or happiness. Commonly used indices of eudaimonic well-being include personal growth and having a sense of purpose and meaning in life (Ryan & Deci, 2001).

Much of the existing research on culture and suppression has employed indexes of hedonic well-being (e.g., life satisfaction, positive affect, negative affect) as the outcome variables of interest, providing a limited view of positive psychological functioning. Following the perspective that the optimal human experience is best conceptualized as a multidimensional phenomenon that includes both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Waterman, 1993), we examined the link of suppression to both aspects of well-being.

The present study sought to improve upon previous research on cultural differences in the link between suppression and psychological well-being in three major ways. First, it focused on suppression in two collectivistic groups that have rarely been compared side by side in emotion regulation research (for an exception, see Soto et al., 2005). Even though both Chinese and Mexican Americans emphasize collectivistic values over individualistic values, each group tends to use different emotion regulation strategies to fulfill important collective tasks, such as the maintenance of social harmony. Second, past research has mostly been concerned with how suppression relates to positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction—the hedonic aspects of well-being. Guided by a broader conceptualization of well-being, we wanted to explore whether suppression would have similar associations to eudaimonic well-being.

Because Chinese culture tends to discourage the expression of positive emotions and Mexican culture tends to value the expression of positive emotions as means of achieving interpersonal harmony, it stands to reason that suppression of positive emotions would be associated with lower hedonic and eudaimonic well-being among Mexican Americans but not Chinese Americans. Therefore, we hypothesized that Mexican Americans would suppress positive emotions less than Chinese Americans (Hypothesis 1), and that suppression of positive emotions would be associated with lower hedonic and eudaimonic well-being among Mexican Americans but not among Chinese Americans (Hypothesis 2). Given that both Chinese and Mexican cultural scripts emphasize the downplaying of negative emotions, we predicted that Mexican Americans and Chinese Americans would not differ in the extent to which they suppress negative emotions, and that suppression of negative emotions would be unrelated to hedonic and eudaimonic well-being for both groups.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The sample consisted of 193 Chinese American and 146 Mexican American college students between the ages of 18 and 23 years. The main sociodemographic characteristics of each sample are presented in Table 1. Compared with the Mexican American sample, the Chinese American sample was older in age and had a higher proportion of male (vs. female) and foreign-born (vs. U.S.-born) participants. A relatively greater percentage of Mexican Americans reported an annual family income below $30,000, and a relatively greater percentage of Chinese American participants reported an annual family income above $100,000. There were no ethnic group differences in the number of years spent in college.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics on Sociodemographic Variables for Total Sample, Chinese Americans, and Mexican Americans

| Total (n = 339) | Chinese Americans (n = 193) | Mexican Americans (n = 146) | t/χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 7.42 | 0.01 | |||

| Male | 36.0% (121) | 42.2% (81) | 27.8% (40) | ||

| Female | 64.0% (215) | 57.8% (111) | 72.2% (104) | ||

| Unknown | 0.9% (3) | ||||

| Age in years | 19.40 (1.34) | 19.55 (1.37) | 19.21 (1.27) | 2.33 | 0.02 |

| Born in United States | 35.75 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 74.0% (251) | 61.7% (119) | 90.4% (132) | ||

| No | 26.0% (88) | 38.3% (74) | 9.6% (14) | ||

| Years in college | 1.93 (1.13) | 2.01 (1.15) | 1.83 (1.10) | 1.43 | 0.15 |

| Family income/year | 9.25 | 0.03 | |||

| Less than $30,000 | 32.4% (110) | 28.0% (52) | 40.3% (58) | ||

| $30,000–$50,000 | 26.8% (91) | 26.3% (49) | 29.2% (42) | ||

| $50,000–$100,000 | 22.4% (76) | 25.8% (48) | 19.4% (28) | ||

| Above $100,000 | 15.6% (53) | 19.9% (37) | 11.1% (16) | ||

| Unknown | 2.7% (9) |

Data reported in the current study were collected from 20 colleges and universities across the United States between January and October 2009, as part of a large research collaborative called the Multi-Site University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC). A number of papers using MUSIC data have been published (e.g., Park, Schwartz, Lee, Kim, & Rodriguez, 2013; Schwartz et al., 2010; for a detailed description of MUSIC, please see Weisskirch et al., 2013). Participants were recruited from courses in education, family studies, human nutrition, psychology, business, and sociology. Those who chose to take part in the study completed an online survey that included the measures described in the next section. As compensation for taking the survey, course credits were given to the participants.

Measures

Expressive suppression.

Items from the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003) were used to measure the extent to which individuals reported hiding or restraining the expression of positive and negative emotions. The item that assessed the suppression of positive emotions reads, “When I am feeling positive emotions, I am careful not to express them.” The item that assessed the suppression of negative emotions reads, “When I am feeling negative emotions, I am careful not to express them.” Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater use of suppression. Single-item measures have been shown to offer important benefits and to be useful in research across a variety of topic areas (Burisch, 1984; Robins, Hendin, & Trzesniewski, 2001). Both items have been used in previous studies involving different ethnic groups, including Chinese (Soto et al., 2011; Su et al., 2013) and Latinos (Gross & John, 2003).

Life satisfaction.

The five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) was used to measure participants’ level of hedonic well-being in terms of global life satisfaction. One of the items from the SWLS reads, “I am satisfied with my life.” Each item was rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). This measure has been validated for use in the United States (Diener et al., 1985) and around the world (Kuppens, Realo,& Diener, 2008). In the current study, the SWLS score has an internal reliability (alpha) of .85 and .86 for Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans, respectively.

Eudaimonic well-being.

The 21-item Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being (QEWB; Waterman et al., 2010) was used to measure participants’ level of eudaimonic well-being. One of the items from the QEWB reads, “My life is centered around a set of core beliefs that give meaning to my life.” Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This measure has been validated on large ethnically diverse samples of college students in the United States (Waterman et al., 2010). In the current study, the QEWB scale score has an internal reliability (alpha) of .81 and .85 for Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans, respectively.

Sociodemographic background.

Participants’ ethnicity, age, gender, number of years spent in college, annual family income, and nativity status (i.e., whether they were born in the United States or not) were examined in this study.

Data Analytic Approach

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to examine ethnic differences in the extent to which positive and negative emotions are suppressed. To test whether ethnicity moderated the relation between suppression and well-being, we used multivariate multiple regression analysis, wherein life satisfaction and eudaimonic well-being were entered as criterion variables and the following variables were entered as predictors: suppression of positive emotions, suppression of negative emotion, ethnicity (dummy coded “0” for Chinese American and “1” for Mexican American), the interaction between suppression of positive emotions and ethnicity, and the interaction between suppression of negative emotions and ethnicity.

Criterion variables that showed statistically significant relationships to the predictors were examined further in univariate hierarchical regression analyses. In Step 1 of the univariate hierarchical regression, suppression of positive emotions and suppression of negative emotions were entered as the main effects of interest. In Step 2, the moderator variable, ethnicity (dummy coded “0” for Chinese American and “1” for Mexican American), was entered. In Step 3, the two-way interaction terms (Suppression of Positive Emotions × Ethnicity; Suppression of Negative Emotions × Ethnicity) were entered to test for the moderating effect of ethnicity on the association between suppression and well-being (life satisfaction or eudaimonic well-being). Raw scale scores for the predictor variables were mean-centered to reduce collinearity between the main effect and the interaction term (Aiken & West, 1991; Cronbach, 1987).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

First, multiple-group confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to examine measurement invariance between the two ethnic groups for each multi-item scale used in cross-ethnic comparisons. For the SWLS, we kept the five items as indicators because it is a five-item scale. We created four parcels for the QEWB (21 items) by first ranking factor loadings and then successively pairing items with the highest and lowest factor loadings in each parcel to equalize the average loadings across parcels (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). Results from the multiple-group confirmatory factor analyses are shown in Table 2. Model 0 is the baseline model with all parameters freely estimated. Model 1 constrained all factor loadings to be equal across the two groups. Model 2 constrained all factor loadings and intercepts to be equal across the two groups. A nonsignificant chi-square difference between Model 0 and Model 1 indicated invariance of the factor loadings, providing evidence for metric equivalence. A nonsignificant chi-square difference between Model 1 and Model 2 indicated invariance of the factor loadings and intercepts, providing evidence for both metric and scalar equivalence. As can be seen in Table 2, the nonsignificant chi-square difference test between Model 0 and Model 1 suggested that that the factor loadings were invariant for Chinese and Mexican Americans on both the SWLS and the QEWB. The chi-square difference test between Model 1 and Model 2 was nonsignificant only for the QEWB, implying that the factor loadings and intercepts were invariant for Chinese and Mexican Americans on the QEWB but not on the SWLS. Previous scholars (e.g., Ham, Wang, Kim, & Zamboanga, 2013; Widaman & Reise, 1997) have noted that intercept invariance is important for making mean-level comparisons, whereas factor loadings invariance is important for examining differences in relationships across groups. Because the goal of our study was about testing group differences in the relation between suppression and psychological well-being, establishing factor loading invariance was more important than establishing intercept invariance.

Table 2.

Measurement Invariance Tests Between Chinese Americans and Mexicans Americans for Life Satisfaction, Eudaimonic Well-Being, and Acculturation

| Models | df | Scaled χ2 | p | CFI | RMSEA (90% CI) | Δχ2(df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS (life satisfaction) | |||||||

| Model 0 | 10 | 16.57 | .09 | .99 | .06 [.00, .11] | ||

| Model 1 | 15 | 21.22 | .13 | .99 | .05 [.00, .09] | 3.53 (5) | .62 |

| Model 2 | 19 | 49.58 | .00 | .95 | .09 [.07, .13] | 35.16 (4) | .00 |

| QEWB (eudaimonic well-being) | |||||||

| Model 0 | 4 | 2.07 | .72 | 1.00 | .00 [.00, .08] | ||

| Model 1 | 8 | 6.31 | .61 | 1.00 | .00 [.00, .08] | 4.27 (4) | .37 |

| Model 2 | 11 | 8.58 | .66 | 1.00 | .00 [.00, .07] | 2.25 (3) | .52 |

| SMAS (acculturation) | |||||||

| Model 0 | 4 | 2.45 | .65 | 1.00 | .00 [.00, .09] | ||

| Model 1 | 8 | 3.10 | .93 | 1.00 | .00 [.00, .03] | 0.86 (4) | .93 |

| Model 2 | 11 | 12.43 | .33 | .99 | .03 [.00, .09] | 11.68 (3) | .01 |

Note. N = 339. Model 0 based on freely estimated factor loadings. Model 1 based on factor loadings constrained to be equal. Model 2 based on factor loadings and intercepts constrained to be equal). Criteria for acceptable fit have ranged from CFI ≥ .90 and RMSEA ≤ .10 to more conservative criteria of CFI ≥ .95 and RMSEA ≤ .06 (e.g., Hu & Bentler, 1999). CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA); CI = confidence interval; SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale; QEWB = Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being; SMAS = Stephenson Multigroup Acculturation Scale.

Next, because participants were nested within colleges and universities, we computed the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to determine whether participants’ scores on two sets of dependent variables (Set 1: suppression of positive emotions and suppression of negative emotions; Set 2: life satisfaction and eudaimonic well-being) varied systematically by site. Using mixed model analysis in Predictive Analytics SoftWare Statistics 18, we derived between-and within-group variance at the level of colleges/universities and then calculated the ICC based on the following formula (Hox, 2010): , where ρ is the ICC, represents between-groups variance, and represents within-group variance. Multilevel modeling is recommended if an ICC value reaches 0.05 or higher (Bliese & Hanges, 2004; Hox, 2010). The computed ICC value was under 0.05 (<0.001 for suppression of positive emotions and for suppression of negative emotions, 0.004 for life satisfaction, and 0.033 for eudaimonic well-being), eliminating the need to use multilevel modeling in the present study.

Because our Chinese and Mexican American samples differed on age, gender, income, and nativity, we tested for demographic differences on the key dependent variables using multivariate analyses of variance. No significant multivariate main effects were detected for the same sets of dependent variables examined in the ICC analyses (i.e., suppression of positive emotions and suppression of negative emotions in the first set; life satisfaction and eudaimonic well-being in the second set). We therefore excluded these demographic variables from subsequent analyses.

Mean Ethnic Differences on Use of Suppression

Table 3 presented the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the main variables for each ethnic group. Multivariate regression analysis involving the two suppression variables revealed a significant effect of ethnicity (Wilks’ λ = .98, F[2, 335] = 3.68, p = .03). There were significant ethnic differences on suppression of positive emotions, F(1, 336) = 7.11, p = .01, , with Chinese Americans (M = 3.37, SE = .10) reporting greater suppression of positive emotions than Mexican Americans (M = 2.95, SE = .12). Chinese Americans (M = 4.25, SE = .11) and Mexican Americans (M = 4.21, SE = .13) did not differ in the extent to which they suppressed negative emotions, F(1, 336) = .06, p = .80.

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among the Main Variables

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Americans (n = 184) | |||||

| 1. Suppression of positive emotions | 3.35 | 1.41 | — | ||

| 2. Suppression of negative emotions | 4.23 | 1.46 | .21* | — | |

| 3. Life satisfaction | 3.68 | 1.06 | .05 | .03 | — |

| 4. Eudaimonic well-being | 3.37 | 0.44 | −.08 | .11 | .31* |

| Mexican Americans (n = 136) | |||||

| 1. Suppression of positive emotions | 2.89 | 1.43 | — | ||

| 2. Suppression of negative emotions | 4.17 | 1.52 | .31** | — | |

| 3. Life satisfaction | 3.94 | 1.15 | −.24* | −.06 | |

| 4. Eudaimonic well-being | 3.52 | 0.46 | −.35** | −.07 | .45** |

p < .01.

p < .001.

Test of Moderation Effects

A Wilks’ lambda of .89, F = 3.66, p < .001 indicated that the overall multivariate multiple regression model was statistically significant. Multivariate regression results were not significant for suppression of positive emotions (Wilks’ λ = .99, F[2, 313] = 1.55, p = .21), suppression of negative emotions (Wilks’ λ = .99, F[2, 313] = 1.57, p = .21), or ethnicity (Wilks’ λ = .98, F[2,313] = 2.94, p = .05). However, a significant multivariate result was found for the interaction between suppression of positive emotions and ethnicity (Wilks’ λ = .97, F[2, 313] = 4.45, p = .01). The interaction between suppression of positive emotions and ethnicity had a significant effect on both life satisfaction, F(1, 314 = 6.35, p = .01,, and eudaimonic well-being, F(1, 314) = 5.67, p = .02, (see Table 4 for detailed results from these univariate regression analyses). Multivariate regression results were not significant for the suppression of negative emotions (Wilks’ λ = .99, F[2, 313] = 1.57, p = .21) or for the interaction between suppression of negative emotions and ethnicity (Wilks’ λ = .99, F[2, 313] = .27, p = .76).

Table 4.

The Moderating Effect of Ethnicity on the Relation Between Expressive Suppression and Psychological Well-Being

| Regression steps | B | SE B | ββ | ΔR2 | ΔF(df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion = Life satisfaction | |||||

| Step 1 (predictors) | .01 | 1.63 (2,317) | |||

| Suppression of positive emotions | −0.12 | 0.06 | −.10 | ||

| Suppression of negative emotions | 0.02 | 0.06 | .01 | ||

| Step 2 (moderator) | .01 | 3.36 (1,316) | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.23 | 0.13 | .10 | ||

| Step 3 (two-way interactions) | .02 | 3.51* (2,314) | |||

| Suppression of Positive Emotions × Ethnicity | −0.33* | 0.13 | −.19* | ||

| Suppression of Negative Emotions × Ethnicity | −0.01 | 0.13 | −.01 | ||

| Criterion = Eudaimonic well-being | |||||

| Step 1 (predictors) | .06 | 9.32** (2,317) | |||

| Suppression of positive emotions | −0.11** | 0.03 | −.24** | ||

| Suppression of negative emotions | 0.04 | 0.03 | .09 | ||

| Step 2 (moderator) | .02 | 5.73* (1,316) | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.12* | 0.05 | .13* | ||

| Step 3 (two-way interactions) | .02 | 3.83* (2,314) | |||

| Suppression of Positive Emotions × Ethnicity | −0.13* | 0.05 | −.18* | ||

| Suppression of Negative Emotions × Ethnicity | −0.04 | 0.05 | −.05 |

Note. N = 320.

p < .05.

p < .001.

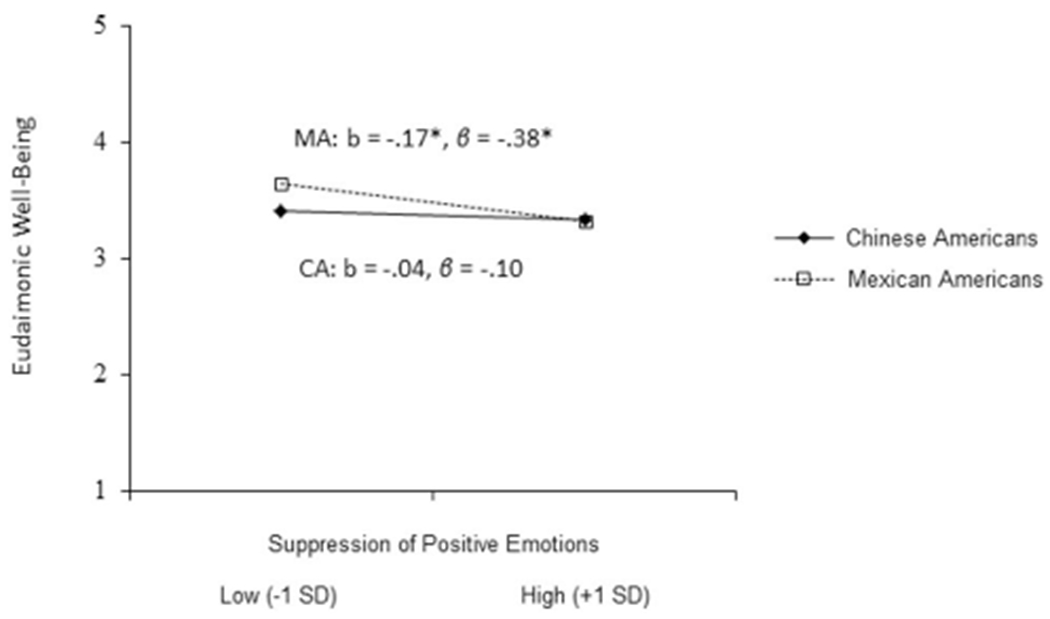

To examine the significant interactions further, we conducted simple slopes analysis at low (0 = Chinese American) and high (1 = Mexican American) levels of the categorical moderator, ethnicity. The simple slopes analysis in which life satisfaction was the criterion indicated that suppression of positive emotions was unrelated to life satisfaction among Chinese Americans (b = .04, SE = .09, p = .61), but it was associated with lower life satisfaction among Mexican Americans (b = −.29, SE = .10, p = .004; see Figure 1). The simple slopes analysis in which eudaimonic well-being was the criterion indicated that suppression of positive emotions was unrelated to eudaimonic well-being among Chinese Americans (b = −.05, SE = .03, p = .16), but it was related to lower eudaimonic well-being among Mexican Americans (b = −.17, SE = .04, p < .001; see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Relationship between suppression of positive emotions and life satisfaction among Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. * p < .01.

Figure 2.

Relationship between suppression of positive emotions and eudaimonic well-being among Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. * p < .001.

Post Hoc Analyses

Acculturation.

Given that the proportion of U.S.-born to foreign-born participants was higher in the Mexican American sample than in the Chinese American sample, we performed post hoc analyses focusing on whether these two groups differed in level of acculturation, and if so, how acculturation may have impacted the results. Acculturation level— defined as the degree of immersion in one’s host culture (Stephenson, 2000)— was measured using 15 items pertaining to American cultural practices from the Stephenson Multigroup Acculturation Scale (SMAS). The items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater level of acculturation. In the current study, the SMAS score has an internal reliability (alpha) of .86 and .87 for Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans, respectively. To examine measurement invariance for this measure, we conducted multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis. We created four parcels by first ranking factor loadings and then successively pairing items with the highest and lowest factor loadings in each parcel. As shown in Table 2, the nonsignificant result from the chi-square difference test between Model 0 and Model 1 indicated that invariance in factor loadings was established. Acculturation level was positively associated with life satisfaction (b = .23, SE =.09, p = .01) and eudaimonic well-being (b = .18, SE = .04, p < .001), Wilks’ λ = .93, F(2, 315) = 12.59,p < .001. However, the pattern of results from the multivariate multiple regression analyses remained the same when acculturation level was included as a full predictor. That is, after controlling for acculturation level, multivariate regression results were significant for the interaction between suppression of positive emotions and ethnicity (for life satisfaction, F[1, 310] = 7.43, p = .007, ; for eudaimonic well-being, F[1, 310] = 8.14, p = .005, ), Wilks’ λ = .97, F(2, 309) = 5.84, p = .003. Multivariate regression results were not significant for the suppression of negative emotions (Wilks’ λ = .99, F[2, 309] = 1.49, p = .23) or for the interaction between suppression of negative emotions and ethnicity (Wilks’ λ = .99, F[2, 309] = .13, p = .88).

Collective identity.

Assuming that more collectivistic Mexican Americans are more likely to value the expression of positive emotions, we conducted another set of analyses focusing on whether Mexican Americans with a stronger collective identity reported lower psychological well-being when suppressing positive emotions than Mexican Americans with a weaker collective identity. Collective identity was measured using eight items from the Aspects of Identity Questionnaire (Cheek, Tropp, Chen, & Underwood, 1994). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not important to my sense of who I am) to 5 (extremely important to my sense of who I am), with higher scores indicating greater level of collective identity. In the current study, the collective identity scale score has an internal reliability (alpha) of .71 and .75 for Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans, respectively. Multivariate regression results indicated a significant interaction between suppression of positive emotions and collective identity (Wilks’ λ = .95, F[2, 125] = 3.10, p = .048). The interaction between suppression of positive emotions and ethnicity had a significant effect on eudaimonic well-being, F(1, 126) = 5.41, p = .02, . To examine the interaction further, we conducted simple slopes analysis at low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of collective identity. The simple slopes analysis indicated that suppression of positive emotions was related to lower eudaimonic well-being among Mexican Americans with a high level of collective identity (b = −.25, SE = .06, p < .001), whereas it was unrelated to eudaimonic well-being among Mexican Americans with a low level of collective identity (b = −.09, SE = .05, p = .07). The interaction between suppression of positive emotions and ethnicity did not have a significant effect on life satisfaction, F(1, 126) = .01, p = .92.

Discussion

Whereas previous studies of emotion regulation have largely focused on cultural groups that represent variations along the dimension of individualism/collectivism (e.g., Asians/Asian Americans, European Americans), the present study examined the role of emotion regulation within cultures that are collectivistic and yet differ in norms regarding the suppression of positive emotions. The present study was also the first to empirically demonstrate that ethnicity may interact with emotion valence in affecting the relation between suppression and psychological well-being.

In the present study, we found that Chinese Americans suppressed more than Mexican Americans with regard to positive emotions only. This result is consistent with previous theoretical and empirical accounts suggesting that the Chinese are socialized to control and subdue the expression of emotions in general, whereas individuals of Latino cultural heritage are socialized to suppress negative emotions but express positive emotions. A study by Soto et al. (2005) also provided evidence suggestive of differences between Chinese and Mexican Americans in the tendency to suppress positive emotions. Specifically, Chinese and Mexican American participants in their study did not differ in the amount of negative emotions experienced during an anticipated startle (i.e., a loud noise that the person knew was coming), but they did differ in the amount of positive emotions expressed with Mexican Americans reporting more positive emotions than Chinese Americans. Even though Soto et al.’s (2005) study focused on emotion experience rather than emotion regulation, their findings hint at differences in the regulation of positive emotions between these two collectivistic ethnic groups.

The current set of findings also suggests that examining the suppression of positive and negative emotions separately may illuminate more nuanced ethnic differences in the association between suppression and psychological well-being. Our data showed that ethnicity moderated the link between suppression and psychological well-being in different ways depending on emotion valence. That is, suppression of positive emotions was related to lower life satisfaction and eudaimonic well-being among Mexican Americans but not among Chinese Americans, whereas suppression of negative emotions was unrelated to these indices of well-being across groups. The observed differences between Chinese and Mexican Americans on the frequency of positive emotional suppression and its relation to well-being are consistent with theoretical perspectives on cultural differences in values surrounding the expression of positive emotions. These findings showcase the heterogeneity of collectivistic cultures and call forth the need to delve deeper into the nature of collectivism. Specifically, our findings lend support to the possibility that suppression of positive emotions is consistent with Chinese norms but deviates from Mexican cultural norms. Failure to enact culturally normative behaviors has been found to be associated with negative psychological functioning (Chentsova-Dutton et al., 2007; Chentsova-Dutton, Tsai, & Gotlib, 2010). This may explain why we found a link between suppression of positive emotions and low psychological well-being among Mexican Americans, for whom expression of positive emotions is vital (Diener & Suh, 2003; Ramirez-Esparza et al., 2008; Triandis et al., 1984).

Expanding the scope of well-being examined in previous research on culture and suppression, this study is the first to focus on the eudaimonic aspect of well-being. Despite the conceptual distinction between life satisfaction and eudaimonic well-being, our study showed that suppression related similarly to these two indicators of well-being. These results imply that, in a given cultural context, suppression of positive or negative emotions may relate to both individuals’ level of happiness and their sense of living a purposeful and meaningful life in a similar fashion. For example, in the Mexican American cultural context, suppression of positive emotions may not only decrease a person’s level of life satisfaction (hedonic well-being) but also sabotage their attempt at becoming a fully functioning individual (eudaimonic well-being).

A few cautions need to be kept in mind when interpreting results from the current study. First, the current study used single-item measures of positive and negative expressive suppression, because validated multiple-item measures are not available. Measurement invariance of these single-item measures could not be confirmed with multiple group confirmatory factor analysis. Moreover, single-item measures may not be as reliable as multiple-item measures, which might explain why the main and interaction effects obtained in this study were modest (although small effects are also common in other studies on suppression). These effects, albeit small, could have important practical implications (Prentice & Miller, 1992). This may be especially likely in this case, because factors related to culture (e.g., Diener, 2000; Diener, Oishi, & Lucas, 2003) and suppression (e.g., Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Westphal, & Coifman, 2004; Gross & John, 2002) can have cumulative effects on the well-being of a large number of people. Moreover, psychological well-being is closely linked to a wide range of mental and physical health consequences (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryan & Frederick, 1997). To reveal stronger and more robust effects of culture and suppression, researchers should develop better measurements of positive and negative emotional suppression in future studies. The use of biological markers of suppression, such as electroencephalogram, skin conductance, and heart rate, could also be considered.

Second, we examined ethnicity as a proxy for culture, along with cultural variables such as acculturation and collective identity. Even though we assumed that specific cultural factors, such as the value of simpatia among Mexican Americans, may underlie differences in suppression between the two ethnic groups, these factors were not directly measured. Testing specific cultural mechanisms behind the observed ethnic differences would be an important next step in future research. Third, the current study relied on self-report measures of suppression and well-being, which limits interpretations and generalizations of our findings. Future studies should try to examine the link between suppression and well-being using experiments and other research designs.

Conclusion

Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of understanding the nuanced ways in which different collectivistic cultural contexts affect emotion regulation and well-being. These differences challenge researchers to seek out alternative explanations for cultural variations in the link between suppression and well-being. Moreover, rather than focusing on suppression more broadly, it would be more fruitful to examine suppression at a more differentiated level. Our study made an important contribution by focusing on positive and negative emotions, but emotions can also be differentiated based on other characteristics of cultural significance, such as level of arousal (Tsai, Knutson, & Fung, 2006) and social orientation (Kitayama, Mesquita, & Karasawa, 2006; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). These characteristics are closely tied to the function of an emotion (Izard, 1991), and to whether suppressing that emotion is adaptive in a given cultural context (Consedine et al., 2002). Understanding specific cultural norms and values surrounding different types of emotions is likely to enrich and advance current knowledge regarding the psychological effects of suppression on diverse groups of individuals.

Contributor Information

Jenny C. Su, National Taiwan University

Irene J. K. Park, Indiana University School of Medicine- South Bend

Janet Chang, Trinity College.

Su Yeong Kim, University of Texas at Austin.

Jessie Dezutter, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

Kyoung Ok Seol, Ewha Womans University.

Richard M. Lee, University of Minnesota

José A. Soto, The Pennsylvania State University

Byron L. Zamboanga, Smith College

Lindsay S. Ham, University of Arkansas

Eric A. Hurley, Pomona College

Elissa Brown, St. John’s University.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford OA, & Hwang K-K (2003). Guilt and shame in Chinese culture: A cross-cultural framework from the perspective of morality and identity. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 33, 127–144. doi: 10.1111/1468-5914.00210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bliese PD, & Hanges PJ (2004). Being both too liberal and too conservative: The perils of treating grouped data as though they were independent. Organizational Research Methods, 7, 400–417. doi: 10.1177/1094428104268542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Westphal M, & Coifman K (2004). The importance of being flexible: The ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science, 15, 482–487. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond M, & Hwang K (1986). The social psychology of the Chinese people. In Bond M (Ed.), The psychology of the Chinese people (pp. 213–266). Hong Kong, China: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burisch M (1984). Approaches to personality inventory construction: A comparison of merits. American Psychologist, 39, 214–227. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.39.3.214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler EA, Lee TL, & Gross JJ (2007). Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion, 7, 30–48. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek JM, Tropp LR, Chen LC, & Underwood MK (1994). Identity orientations: Personal, social, and collective aspects of identity. Paper presented at the 102nd annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Hastings PD, Rubin KH, Chen H, Cen G, & Stewart SL (1998). Child-rearing attitudes and behavioral inhibition in Chinese and Canadian toddlers: A cross-cultural study. Developmental Psychology, 34, 677–686. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Swartzman LC (2001). Health beliefs and experiences in Asian cultures. In Kazarian SS & Evans DR (Eds.), Handbook of cultural health psychology (pp. 389–410). San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Chentsova-Dutton YE, Chu JP, Tsai JL, Rottenberg J, Gross JJ, & Gotlib IH (2007). Depression and emotional reactivity: Variation among Asian Americans of East Asian descent and European Americans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 776–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chentsova-Dutton YE, Tsai JL, & Gotlib IH (2010). Further evidence for the cultural norm hypothesis: Positive emotion in depressed and control European American and Asian American women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 284–295. doi: 10.1037/a0017562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung RYM, & Park IJK (2010). Anger suppression, interdependent self-construal, and depression among Asian American and European American college students. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 517–525. doi: 10.1037/a0020655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Magai C, & Bonanno GA (2002). Moderators of the emotion inhibition-health relationship: A review and research agenda. Review of General Psychology, 6, 204–228. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ (1987). Statistical tests for moderator variables: Flaws in analyses recently proposed. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 414–417. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.102.3.414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Oishi S, & Lucas RE (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, & Suh EM (2003). National differences in subjective well-being. In Kahneman D, Diener E, & Schwarz N (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 434–452). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, & Smith HE (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2, 271–299. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2002). Wise emotion regulation. In Feldman Barrett L & Salovey P (Eds.), The wisdom of feelings: Psychological processes in emotional intelligence (pp. 297–318). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & Levenson RW (1997). Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 95–103. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.1.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Richards JM, & John OP (2006). Emotion regulation in everyday life. In Snyder DK, Simpson JA, & Hughes JN (Eds.), Emotion regulation in families: Pathways to dysfunction and health (pp. 13–35). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Wang Y, Kim SY, & Zamboanga BL (2013). Measurement equivalence of the Brief Comprehensive Effects of Alcohol Scale in a multiethnic sample of college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 341–363. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review, 106, 766–794. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ (2010). Multilevel analysis. Techniques and applications. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternations. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang KK, & Chang J (2009). Self-cultivation: Culturally sensitive psychotherapies in Confucian societies. The Counseling Psychologist, 37, 1010–1032. doi: 10.1177/0011000009339976 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE (1991). The psychology of emotions. New York, NY: Plenum Press. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0615-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Mesquita B, & Karasawa M (2006). Cultural affordances and emotional experience: Socially engaging and disengaging emotions in Japan and the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 890–903. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Realo A, & Diener E (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 66–75. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, & Jia X (2004). Face negotiation in conflict resolution in the Chinese context. Intercultural Communication Studies, 13, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, & Fu V (1990). A comparison of child rearing practices among Chinese, immigrant Chinese, and Caucasian-American parents. Child Development, 61, 429–433. doi: 10.2307/1131104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, & Widaman KF (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, & Kemmelmeier M (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IJK, Schwartz SJ, Lee RM, Kim M, & Rodriguez L (2013). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and antisocial behaviors among Asian American college students: Testing the moderating roles of ethnic and American identity. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 166–176. doi: 10.1037/a0028640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DA, & Miller DT (1992). When small effects are impressive. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 160–164. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Esparza N, Gosling SD, & Pennebaker JW (2008). Paradox lost: Unraveling the puzzle of simpatía. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39, 703–715. doi: 10.1177/0022022108323786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Hendin HM, & Trzesniewski KH (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 151–161. doi: 10.1177/0146167201272002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby MB, Falk CF, Heine SJ, Villa C, & Silberstein O (2012). Not all collectivisms are equal: Opposing preferences for ideal affect between East Asians and Mexicans. Emotion, 12, 1206–1209. doi: 10.1037/a0029118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Frederick C (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65, 529–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Singer B (1998). The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 1–28. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0901_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Singer B (2000). Interpersonal flourishing: A positive health agenda for the new millennium. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 30–44. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0401_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Hurley EA, Zamboanga BL, Park IJK, Kim SY, … Green AD (2010). Communalism, familism and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather? Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 548–560. doi: 10.1037/a0021370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkodriani GM, & Gibbons JL (1995). Individualism and collectivism among university students in Mexico and the United States. The Journal of Social Psychology, 135, 765–772. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1995.9713979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soto JA, Levenson RW, & Ebling R (2005). Cultures of moderation and expression: Emotional experience, behavior, and physiology in Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. Emotion, 5, 154–165. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto JA, Perez CR, Kim Y-H, Lee EA, & Minnick MR (2011). Is expressive suppression always associated with poorer psychological functioning? A cross-cultural comparison between European Americans and Hong Kong Chinese. Emotion, 11, 1450–1455. doi: 10.1037/a0023340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson M (2000). Development and validation of the Stephenson Multigroup Acculturation Scale (SMAS). Psychological Assessment, 12, 77–88. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su JC, Lee RM, & Oishi S (2013). The role of culture and self-construal in the link between expressive suppression and depressive symptoms. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 316–331. doi: 10.1177/0022022112443413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Marín G, Lisansky J, & Betancourt H (1984). Simpatía as a cultural script of Hispanics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1363–1375. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Chentsova-Dutton Y, Freire-Bebeau L, & Przymus DE (2002). Emotional expression and physiology in European Americans and Hmong Americans. Emotion, 2, 380–397. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.2.4.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Knutson B, & Fung HH (2006). Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 288–307. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, & Levenson RW (1997). Cultural influences on emotional responding: Chinese American and European American dating couples during interpersonal conflict. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 28, 600–625. doi: 10.1177/0022022197285006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman AS (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 678–691. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman AS, Schwartz SJ, Zambonga BL, Ravert RD, Williams MK, Agocka VB, … Donnellan MB (2010). The questionnaire of eudaimonic well-being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 41–61. doi: 10.1080/17439760903435208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Tellegen A (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 219–235. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskirch RS, Zamboanga BL, Ravert RD, Whitbourne SK, Park IJK, Lee RM, & Schwartz SJ (2013). An introduction to the composition of the Multi-Site University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC): A collaborative approach to research and mentorship. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 123–130. doi: 10.1037/a0030099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook MT (1976). Positive affect: A method of content analysis for verbal samples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 44, 715–719. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.44.5.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, & Reise SP (1997). Exploring the measurement invariance of psychological instruments: Applicants in the substance use domain. In Bryant KJ, Windle M, & West SG (Eds.), The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance abuse research (pp. 281–324). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/10222-009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka A (1994). Emotion, language, and cultural scripts. In Kitayama S & Markus HR (Eds.), Emotion and culture (pp. 133–196). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Wu DYH (1996). Chinese childhood socialization. In Bond MH (Ed.), The handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 143–154). Hong Kong, China: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]