Abstract

Objective

To develop a virtual reality simulation training programme, and further verify the effect of the programme on improving the response capacity of emergency reserve nurses confronting public health emergencies.

Design

A prospective quasiexperimental design with a control group.

Participants

A total of 120 nurses were recruited and randomly divided into the control group and the intervention group.

Intervention

Participants underwent a 3-month training. The control group received the conventional training of emergency response (eg, theoretical lectures, technical skills and psychological training), while the intervention group underwent the virtual reality simulation training in combination with skills training. The COVID-19 cases were incorporated into the intervention group training, and the psychological training was identical to both groups. At the end of the training, each group conducted emergency drills twice. Before and after the intervention, the two groups were assessed for the knowledge and technical skills regarding responses to fulminate respiratory infectious diseases, as well as the capacity of emergency care. Furthermore, their pandemic preparedness was assessed with a disaster preparedness questionnaire.

Results

After the intervention, the scores of the relevant knowledge, the capacity of emergency care and disaster preparedness in the intervention group significantly increased (p<0.01). The score of technical skills in the control group increased more significantly than that of the intervention group (p<0.01). No significant difference was identified in the scores of postdisaster management in two groups (p>0.05).

Conclusion

The virtual reality simulation training in combination with technical skills training can improve the response capacity of emergency reserve nurses as compared with the conventional training. The findings of the study provide some evidence for the emergency training of reserve nurses in better response to public health emergencies and suggest this methodology is worthy of further research and popularisation.

Keywords: public health, infectious diseases, health & safety, education & training (see medical education & training), COVID-19

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study established a novel emergency nursing training protocol for improving the response capacity of emergency reserve nurses confronting an infectious disease epidemic or even pandemic.

Virtual reality simulation training protocol enables nurses to quickly understand the environment and layout of the infectious department, and be familiar with the patient care process.

An emergency reserve nursing team aiming to quickly respond to respiratory epidemic was built based on the virtual reality training, which gained relatively robust and generalisable results.

The participants recruited from one hospital and a relatively small sample size may limit the reference value of the study.

In the Methods section, virtual reality training included some nursing skills practice, so the training time of technical skills in the intervention group was reduced; however, the results showed that the training time of technical skills should be increased in the future.

Introduction

As the virulent public health crisis, the COVID-19 has resulted in substantial deaths worldwide.1 Nurses have played extremely important roles in the prevention and treatment of the COVID-19 pandemic.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses are urgently called from different areas to provide help. In order to effectively respond to the respiratory infectious disease pandemic, nurses need to quickly learn the comprehensive professional knowledge and skills.3 The professional training must be carried out as soon as possible so that they can quickly master the correct donning and doffing of personal protective equipment (PPE),4 5 the management of critically ill patients,6 7 the prevention and control of nosocomial infection, etc.6 8 9

Ideally, in order to improve the preparations for pandemics, planning should be made in advance and a large number of medical staff should be sufficiently trained.3 9 Due to the abrupt, highly transmissible and detrimental nature of acute infectious diseases, it is difficult to deliver clinical training in the real ward. Thus, training programmes, for example, emergency drills, simulation-based training, tabletop exercises, role-playing and online learning, are expected to develop and support healthcare workers to gain more experience in responding to pandemics.10–14 However, the previous training programmes were commonly ineffective in reflecting the reality and providing practical experience for the recent outbreak of COVID-19. As a result, the nurses naturally lacked the ability to deal with emergencies15–22 and felt enormous psychological pressure in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.19 20 23 24

Simulation-based training in response to epidemics has lots of advantages, for example, providing a safe environment to train medical staff to quickly master specific technical skills, working closely with the team and optimising work processes and systems,5 20 while protecting patients from further harm.25 26 In China, the virtual reality simulation programmes for the respiratory infectious diseases were mainly used to train the students majoring in preventive medicine and public health27 on conducting epidemic investigation, sampling, disinfection and isolation, etc. Very few virtual reality simulation programmes, covering the medical condition, treatment and care of patients, are developed to train nurses in response to a respiratory infectious disease epidemic. Thus, this study aims to develop a virtual reality simulation training programme incorporated with the COVID-19 cases, and further verify the effect of the programme on improving the response capacity of emergency reserve nurses confronting public health emergencies. The highly qualified trainees are expected to build up an emergency reserve nursing team to respond to epidemic at local cities or other cities after training.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted at a general hospital in Hengyang, Hunan Province, China. From January to March 2020, the hospital treated 80% of the local patients confirmed to have COVID-19; and by 2 March, all those patients recovered and were discharged from the hospital. Since then, there has been no more newly confirmed COVID-19 case in the region. In May 2020 (2 months after the stability of the local epidemic situation), 120 eligible nurses were enrolled in this study and randomly divided into control group and intervention group according to a computer-generated random numbers table. When the nurse passed the assessment after training, he/she would be selected into the emergency nurse bank of the local public health emergency.

Design

This is a prospective quasiexperimental design with a control group.

Ethics

After signing the informed consent, all participants voluntarily participated in the study and were informed they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. Their personal information could only be accessed by the authors.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in this study. This study/article focused on a novel training mode with virtual reality technology for nurses dealing with public health emergencies.

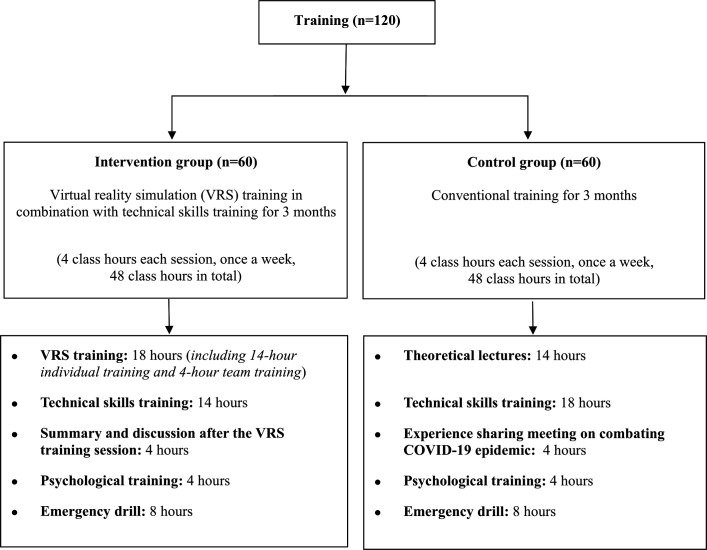

Training

From May to July 2020, the nurses in the control and intervention groups were trained according to the following programme.

The control group received conventional training

A 10-member emergency nursing instructor team was set up, consisting of the experts in medical treatment, nursing care, nosocomial infection control, psychological support and teaching. Some of them had the experience of working on the front line to fight against COVID-19. The instructors were responsible for teaching theories, delivering training on technical skills and organising emergency drills. The 3-month training had 12 sessions with 48 class hours in total (figure 1), including theoretical lectures, individual technical skills training, psychological training, an experience sharing meeting on the medical work in the COVID-19 pandemic and emergency drill for trainees in the background of a respiratory epidemic outbreak. The instructors were divided into two groups for supervising exercise and evaluating the individual performance of each trainee in emergency drill with the emergency care capability rating scale.28 As for the content of training, it included the interim clinical guidance for the management of patients with COVID-19, infection control guidance, disinfection, quarantine, psychological training, as well as the preparation of PPE. Especially, much importance was attached to the training on how to practise self-protection and relieve the nurses’ psychological stress. The 14 basic technical skills in the training included donning and doffing of PPE, disinfection and isolation, respiratory tract sampling, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, sputum aspiration, oxygen inhalation, aerosol inhalation, tracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, etc. The training and assessment plan is detailed in online supplemental appendix.

Figure 1.

Training plan for reserve nurses in two groups.

bmjopen-2021-048611supp001.pdf (87.3KB, pdf)

The intervention group received virtual reality simulation training in combination with technical skills training

With the assistance of computer-based virtual reality equipment, there were three steps to fulfil this project.

First, an instructor team was set up and the training cases were prepared. Different from the instructor team in the control group, the instructor team in the intervention group had one specific teacher for virtual training and information technology support. The instructor team was tasked with selecting three typical COVID-19 cases in which the private details of the patients were removed. The three cases included one severe case of an adult patient, one critical case of an elderly patient with complications such as diabetes and one critical case of an 8-year-old child patient. The whole processes of treatment in those three cases, such as the commonly used skills, nursing measures and possible difficulties in nursing care, were analysed, identified and factored into the cases of virtual reality simulation training.

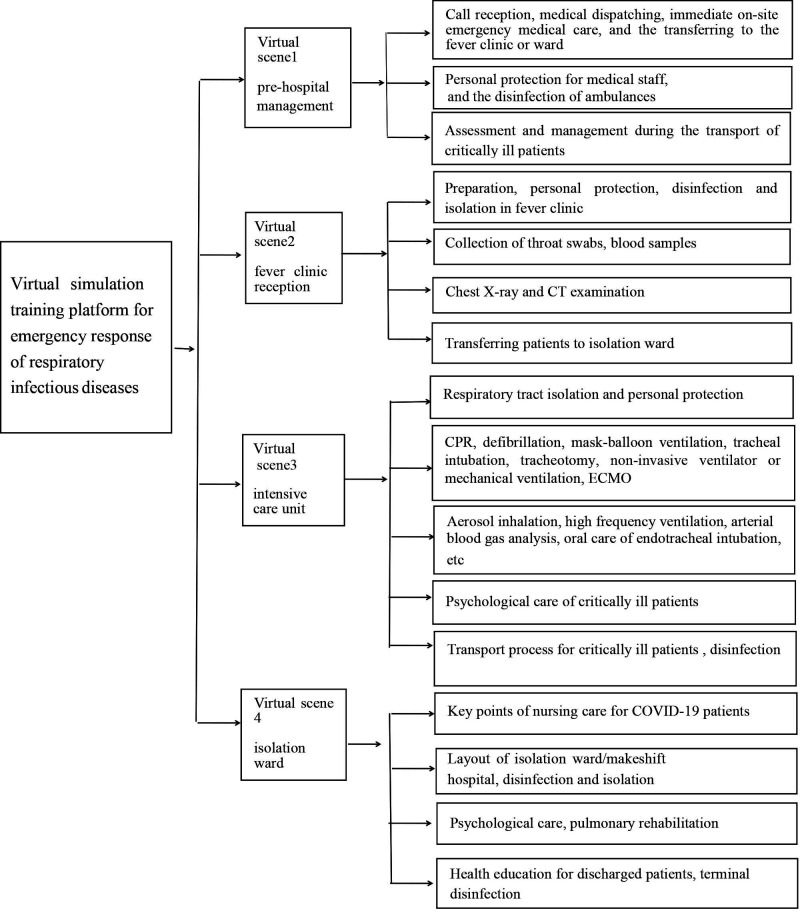

Second, the virtual scene was set and the platform was constructed. Four virtual scenes, including prehospital management, fever clinic reception, intensive care unit (ICU) and isolation ward, were set with the aim of familiarising the trainees with different layout of zone and working environments. Meanwhile, the cases could simulate the real clinical symptoms, clinical manifestations, disease progression, diagnosis and treatment, nursing care, psychological changes, the standard operating procedures of disinfection and isolation, etc. The relevant tasks included all the key elements of the guidance for management of patients and infection control on COVID-19 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Design of virtual simulation training platform for emergency response of respiratory infectious diseases. CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Third, training was delivered. The training lasted 4 hours/week for 3 months (figure 1). Compared with the trainees in the control group, the trainees in the intervention group received both the individual and team training based on virtual reality technology. Besides, the trainees were also required to attend individual technical skills training. Each session comprised virtual reality simulation training for 2 hours, the practice of technical skills on multifunctional simulation/models for 1.5 hours, a recapping and exchanging of views on the handling of unexpected situations or emergencies, a meeting for sharing nursing experience and a group discussion on the relevant questions and procedures to the cases for 0.5 hour. The psychological training and the emergency drill at the end of the training were the same as those in the control group. The trainees were allowed to make appointments on the hospital virtual training platform for repeating and reviewing the practices in their spare time. Each trainee can make two appointments of training under a two-instructor on-spot supervision and have 2 hours allowed for each practice. The training and assessment plan is detailed in online supplemental appendix.

Evaluation

Main outcome

The emergency care capability rating scale

The instructors as the judge were responsible for evaluating the nurses of the two groups for their capacities of emergency care before and after the intervention. The design of emergency care capability rating scale for nursing staff was based on the study of Wang and Liu,28 which focused on five dimensions with 100 points in total, including the ability of occupational protection, disinfection and quarantine (20), the observation and judgement of disease (20), the preliminary examination, classification and treatment of the patients in severe or critical condition (20), cooperation and coordination (20), as well as the assessment and management of crisis (20). The higher the score the nurse achieved, the greater the capability of the nursing staff to deal with emergencies. At the end of the training, all the trainees should undergo twice drills. The capacity score of emergency care was the average of the results of the twice drills.

Before the assessment, we conducted a pilot study to assess the reliability of the scale. The Cronbach’s α was 0.79, indicating the reliability of the scale was acceptable.

Secondary outcome

Assessment of theories and skills

The trainees in the two groups were assessed for their relevant theoretical knowledge and skills before and after the intervention. The theoretical examination was conducted through multiple choice question (MCQ) test.29 The skill assessment was completed on-site during the practice. Each trainee was allowed to make two attempts during the skill assessment, with the higher one achieved in the two attempts taken as the assessment result.

The Chinese version of Disaster Preparedness Evaluation Tool

This scale was used to assess the nursing staff for their preparedness for possible pandemic. Proposed by Li and Sheng,30 the scale was translated and adjusted culturally from Tichy’s scale.31 The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.865, involving 45 items of three dimensions: the knowledge about disaster (13 items), the skills regarding disaster (11 items) and postdisaster management (21 items). The scale covered risk reduction, disease prevention and health promotion, policymaking and development, ethics, legal practices and liabilities, communication and information sharing, the education about and preparedness for disaster, community care, individual and home care, psychological care, the care for vulnerable groups, the long-term rehabilitation of individual, family and community, etc, which could fully reflect the state of disaster preparedness among the nursing staff. The items were scored 1–6 points from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. The higher the score was, the more prepared the nursing staff were.

Statistical analysis

All data were input into SPSS V.18.0 and were statistically analysed. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the demographic data. The continuous data were summarised using mean and SD, and categorical data were summarised using percentage. The χ2 test and Student’s t-test were used to analyse the comparability of the baseline between the two groups. The differences before and after intervention in the results of Disaster Preparedness Evaluation Tool (DPET), theoretical and skill assessments and the capacity of emergency care scores between the groups were evaluated by the Student’s t-test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic data

Table 1 presents the demographic data comparison between the two groups of participants. The majority of the 120 subjects in this study were women (control group: 91.7%, intervention group: 88.3%). The differences in gender, age, highest degree and work experience between the two groups were not statistically significant (p>0.05) and were comparable.

Table 1.

Demographic data (n=120)

| Variable | Control group (n=60) n (%) |

Intervention group (n=60) n (%) |

t/χ2 | P value |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 5 (8.3) | 7 (11.7) | 0.093 | 0.761 |

| Female | 55 (91.7) | 53 (88.3) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤30 | 29 (48.3) | 28 (46.7) | 0.255 | 0.754 |

| 31–39 | 24 (40.0) | 24 (40.0) | ||

| ≥40 | 7 (11.7) | 8 (13.3) | ||

| Clinical experience (years) | ||||

| ≤5 | 26 (43.3) | 23 (38.3) | 0.111 | 0.912 |

| 6–14 | 21 (35.0) | 25 (41.7) | ||

| ≥15 | 13 (21.7) | 12 (20.0) | ||

| Highest degree | ||||

| Diploma/associate degree | 11 (18.3) | 10 (16.7) | 0.060 | 0.970 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 40 (66.7) | 41 (68.3) | ||

| Master’s degree | 9 (15.0) | 9 (15.0) | ||

| Professional title | ||||

| Primary | 29 (48.3) | 30(50.0) | 0.165 | 0.921 |

| Intermediate | 21 (35.0) | 19(31.7) | ||

| Senior | 10 (16.7) | 11(18.3) | ||

| Work experience in emergency/intensive care unit | ||||

| Yes | 22 (36.7) | 23 (38.3) | 0.036 | 0.850 |

| No | 38 (63.3) | 37 (61.7) | ||

| Work experience in infectious departments | ||||

| Yes | 21 (35.0) | 23 (38.3) | 0.144 | 0.705 |

| No | 39 (65.0) | 37 (61.7) | ||

| Experience of caring for patients with COVID-19/SARS | ||||

| Yes | 15 (25.0) | 17 (28.3) | 0.170 | 0.680 |

| No | 45 (75.0) | 43 (71.7) | ||

| Hospital department of work | ||||

| Medical ward | 19 (31.7) | 19 (31.7) | 0.270 | 0.998 |

| Surgical ward | 14 (23.3) | 15 (25.0) | ||

| Emergency department | 8 (13.3) | 7 (11.7) | ||

| Intensive care unit | 8 (13.3) | 9 (15.0) | ||

| Paediatrics department | 5 (8.3) | 5 (8.3) | ||

| Others | 6 (10.0) | 5 (8.3) | ||

Comparison of the DPET scores between two groups before and after intervention

Prior to intervention, there was no significant difference found in the scores of disaster preparedness between the two groups (p>0.05, table 2). After intervention, however, the total score of disaster preparedness of the intervention group was significantly higher than that of the control group (p<0.001, table 2). The scores of knowledge and skills regarding disaster in the intervention group were significantly higher than those in the control group (p<0.001, table 2), while the scores of postdisaster management showed no statistical significance between two groups (p>0.05, table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the DPET scores between groups before and after intervention (n=120)

| Control group (n=60) (M±SD) |

Intervention group (n=60) (M±SD) |

t | P value | |

| Knowledge regarding disaster | ||||

| Preintervention | 101.73±17.94 | 104.38±14.47 | 0.891 | 0.375 |

| Postintervention | 122.00±12.79 | 131.22±6.99 | 4.900 | <0.001 |

| Skills regarding disaster | ||||

| Preintervention | 52.20±10.52 | 51.55±8.72 | 0.369 | 0.713 |

| Postintervention | 69.42±7.89 | 75.95±4.52 | 5.566 | <0.001 |

| Postdisaster management | ||||

| Preintervention | 24.08±5.68 | 23.82±4.68 | 0.281 | 0.779 |

| Postintervention | 27.47±4.77 | 28.05±3.26 | 0.782 | 0.436 |

| Total score | ||||

| Preintervention | 178.02±30.60 | 179.75±20.23 | 0.366 | 0.715 |

| Postintervention | 218.88±21.34 | 235.22±10.75 | 5.295 | <0.001 |

Bold p values represent significant values. SD using t (t-test).

DPET, Disaster Preparedness Evaluation Tool.

Comparison of the scores of theoretical and skill assessments and the capacity of emergency care before and after intervention

There was no significant difference observed in the scores of theoretical and skill assessments or the capacity of emergency care between the two groups before intervention (p>0.05, table 3). After intervention, however, both the score of theoretical assessment and the capacity of emergency care were improved in the two groups. The score of theoretical assessment and the capacity of emergency care in the intervention group were significantly higher than those in the control group (p<0.001, table 3), while the score of technical skills in the control group was slightly higher than that in the intervention group (p<0.01, table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the scores of theoretical and skill assessments and the capacity of emergency care between groups before and after intervention (n=120)

| Control group (n=60) (M±SD) |

Intervention group (n=60) (M±SD) |

t | P value | |

| Theoretical assessment | ||||

| Preintervention | 65.12±7.04 | 65.62±7.16 | 0.386 | 0.700 |

| Postintervention | 82.92±4.55 | 86.62±3.91 | 4.783 | <0.001 |

| Technical skills | ||||

| Preintervention | 71.13±4.57 | 71.77±5.66 | 0.035 | 0.972 |

| Postintervention | 90.35±3.38 | 88.47±4.19 | 2.708 | 0.008 |

| Capacity of emergency care | ||||

| Preintervention | 63.10±7.23 | 63.93±6.65 | 0.657 | 0.516 |

| Postintervention | 81.97±4.45 | 85.35±3.93 | 4.416 | <0.001 |

Bold p values represent significant values.

Discussion

In this quasiexperimental study, we developed a virtual reality simulation training programme that included typical COVID-19 cases and evaluated the effectiveness of a novel virtual simulation training in the reserve nurses for an infectious respiratory disease pandemic. One hundred and twenty reserve nurses, as the sample for this study, participated in the training programme and completed both the pretest and post-test evaluation. All the participants were Chinese clinical nurses who volunteered to be the emergency reserve nurses for public health emergencies. The results of this study showed that the virtual simulation technology in combination with technical skills training can significantly improve the preparedness of reserve nurses for the respiratory infectious emergencies. The theoretical assessment and the emergency care capability of the intervention group were significantly increased compared with those in the control group after conventional training (p<0.001). These findings indicated a critical need for virtual simulation training for the reserve nurses before they went to the front line of responding to infectious respiratory disease.

Different from the conventional training, this virtual reality simulation training provided a simulated scene of the isolation ward. The training was flexible and could simulate real-world settings. Thus, it was convenient for the trainees to quickly get familiar with the special layout of zone, the working environment and the standard procedure. These were extremely important for the emerging infectious diseases. Compared with other virtual simulation programmes,32–34 we integrated typical cases of COVID-19 into our training programme. Since the COVID-19 has not subsided worldwide, it still is a hard and longtime work to deal with the epidemic. Thus, it is crucially important to train the technical skills, and carry out emergency drills in the background of COVID-19 for emergency reserve nurses, so as to help the trainees to quickly master the essentials, adapt to the work context and improve their emergency rescue abilities. In the immersive learning environment of our programme, the trainees can learn the theories and practise technical skills, which are essential to treat and care patients with COVID-19.35 Moreover, this programme can prevent the trainees from directly contacting the patients with COVID-19, thus reducing the risk of infection and ensuring the safety of the trainees.25 This virtual reality simulation training programme also has the mode of team/group training, the nursing trainees can log into the system in different roles, conduct teamwork training and real-time interaction,36–39 which can mobilise the trainees rapidly to collaborate with team members in completing their own tasks. Since this training programme has been included as part of the virtual teaching platform operated by the hospital, the nursing trainees can make appointments for repeating and reviewing what they have learnt during their spare time, which breaks the time and place limits of conventional training.

Several studies reported the application of virtual reality simulation training in medical/nursing training.37 40–48 Nayahangan et al9 systematically reviewed the training and education of medical staff during the infectious disease epidemic, and indicated that the studies about the simulation-based training mostly focused on training practical skill-related clinical procedures. Nair and Kaufman7 used simulation to train ICU staff and non-critical care unit staff to familiarise themselves with the revised COVID-19 care procedures, including respiratory failure, circulatory failure, bedside ultrasound, bedside ICU procedures and elements of COVID-19-specific care, finally found it had a good training effect. Our programme was designed for reserve nurses and simulated the clinical manifestations, disease progression, psychosocial problems of patients with COVID-19, as well as diagnosis and treatment, nursing care and standard procedures of disinfection and isolation. In our study, trainees in the intervention group received virtual reality simulation training in combination with technical skills training, which was similar to the previous study by Ragazzoni et al.49 They used virtual reality simulation to train medical staff on the operational public health skills related to the infection control and Ebola treatment management and also proposed a model of the virtual reality simulation in combination with hybrid skills training exercises.

After the intervention, the scores of technical skills in the control group (90.35±3.38) were slightly higher than those in the intervention group (88.47±4.19) (p<0.01), which may be explained by the two reasons: first, the technical skills training time of the intervention group was 4 hours less than that of the control group; second, the trainees got more accustomed to the traditional way of skill practice. Therefore, in the future training, the skills training time for the virtual simulation group will be added four more hours to the same level as that of the control group. It is essential that more attention should be brought to ensure the balance between virtual training and conventional training.50–52 In addition, the scores of postdisaster management were low among the nurses in the two groups before intervention. After intervention, however, the scores were only slightly improved in both groups, with no statistical difference between the two groups (p>0.05). This finding demonstrated that the emergency reserve nurses in the region currently lacked the knowledge of post-traumatic stress, suggesting our training programme needs to prioritise postdisaster care and post-traumatic recovery of the nurses in the future.

In the future, we will optimise our training model by integrating simulator training with that in the three-dimensional (3D) virtual environment, so as to give full play to their respective advantage, thus improving the overall clinical capabilities of nurses. Besides, we can explore the virtual reality team training for interdisciplinary cooperation. We also hope to provide the training for other universities and hospitals based on the virtual experiment project platform in China, and even for the institutes outside of China.

Limitations

There are some limitations faced by our study. First, the sample size of the study was small, as all of the participants came from the same hospital, thus restricting the reference value of the study. Second, due to limited resources, the virtual scene of mobile cabin hospital was not constructed in the virtual training programme, which will be improved in the future study. Third, the time of skills training needs to be extended, as there was a lack of attention paid to the training related to postdisaster care and post-traumatic recovery, which should also be improved in the future.

Conclusion

Our study has developed a virtual reality simulation training programme that included typical COVID-19 cases. As for the training on the pandemic response of reserve nurses, the virtual reality simulation training in combination with technical skills training is effective in achieving better outcomes than the conventional training. This training programme shows more advantages in improving the theoretical knowledge, the capacity of emergency care and the preparedness for pandemic, which makes it applicable to the emergency training for nurses in better response to public health emergencies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in this study and the staff from the Clinical Simulation Center in the University of South China.

Footnotes

Contributors: DZ and Y-PZ designed the study. HL, PH, DW and WenY helped develop the study measures and data collection. WeiY and YC contributed to study delivery and interpretation of data. DZ, YJ and Y-PZ wrote the manuscript and all the authors read the final manuscript and approved its submission.

Funding: This study was partially supported by the grants from Shaanxi Province (SGH140537), the Xi’an Jiaotong University Fund (202107164), the Fund of Hunan Social Science Achievement Appraisal Committee (XSP21YBC228), the Hunan Anti-COVID-19 Special Project (2020SK3040) and the fund of innovative programme on the COVID-19 prevention and treatment from Hengyang Science and Technology Bureau (202010031581).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Nanhua Hospital, University of South China (2020-ky-49).

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center , 2020. Available: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Accessed 10 Aug 2020].

- 2.Chen Q, Lan X, Zhao Z, et al. Role of anesthesia nurses in the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. J Perianesth Nurs 2020;35:453–6. 10.1016/j.jopan.2020.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li L, Xv Q, Yan J. COVID-19: the need for continuous medical education and training. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:e23. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30125-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell DN, Perl TM. Cutrell JBJCID. "the art of war" in the Era of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen L, Rasmussen CS, Benfield T, et al. A randomized trial of Instructor-Led training versus video lesson in training health care providers in proper Donning and Doffing of personal protective equipment. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020;14:514–20. 10.1017/dmp.2020.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hou X, Hu W, Russell L, et al. Educational needs in the COVID-19 pandemic: a Delphi study among doctors and nurses in Wuhan, China. BMJ Open 2021;11:e045940. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nair SS, Kaufman B. Simulation-Based Up-Training in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Simul Healthc 2020;15:447–8. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phua J, Weng L, Ling L, et al. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:506–17. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30161-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nayahangan LJ, Konge L, Russell L, et al. Training and education of healthcare workers during viral epidemics: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2021;11:e044111. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz JV, Lister P, Ortiz JR, et al. Development of a severe influenza critical care curriculum and training materials for resource-limited settings. Critical Care 2013;17. 10.1186/cc12437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MenkinSmith L, Lehman-Huskamp K, Schaefer J, et al. A pilot trial of online simulation training for Ebola response education. Health Secur 2018;16:391–401. 10.1089/hs.2018.0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu S-M, Chien L-J, Tseng S-H, et al. A No-Notice drill of hospital preparedness in responding to Ebola virus disease in Taiwan. Health Secur 2015;13:339–44. 10.1089/hs.2015.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinson E. Managing bioterrorism mass casualties in an emergency department: lessons learned from a rural community hospital disaster drill. Disaster Manag Response 2007;5:18–21. 10.1016/j.dmr.2006.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams JJ, Lisco SJ. Ebola: urgent need, rapid response. Simul Healthc 2016;11:72–4. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao-Hua XU, Sheng Y, Zhen LI. A cross-sectional survey of the disaster preparedness of nurses in China 2016.

- 16.Jinlei BAO BS, Hui Z, et al. Investigation on disaster preparedness of clinical nurses going to Wuhan to fight against epidemic diseases in Jilin Province. Chinese Nurs Res 2020;34:938–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Usher K, Mills J, West C, et al. Cross-sectional survey of the disaster preparedness of nurses across the Asia-Pacific region. Nurs Health Sci 2015;17:434–43. 10.1111/nhs.12211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achora S, Kamanyire JK. Disaster preparedness: need for inclusion in undergraduate nursing education. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2016;16:e15–19. 10.18295/squmj.2016.16.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huiping WANG FZ, Weihong LIU, et al. A survey on the disaster preparedness of clinical nurses in epidemic period of novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Nurs Admin 2020;20:229–33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chunzi YY LIU, Huijuan LIU, et al. Disaster preparedness of nurses in three COVID-19 designated hospitals in Beijing and its influencing factors: a cross-sectional study. Acad J Chinese Pla Med School 2020;41:237–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Sullivan TL, Dow D, Turner MC, et al. Disaster and emergency management: Canadian nurses' perceptions of preparedness on hospital front lines. Prehosp Disaster Med 2008;23:s11–19. 10.1017/S1049023X00024043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taskiran G, Baykal U. Nurses' disaster preparedness and core competencies in turkey: a descriptive correlational design. Int Nurs Rev 2019;66:165–75. 10.1111/inr.12501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pérez-Raya F, Cobos-Serrano JL, Ayuso-Murillo D, et al. COVID-19 impact on nurses in Spain: a considered opinion survey. Int Nurs Rev 2021;68:248–55. 10.1111/inr.12682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tosun AS, Gündodu N, Ta F. Anxiety levels and Solution‐Focused thinking skills of nurses and midwives working in primary care during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a descriptive correlational study. J Nurs Manag 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Lin M, Wang X, et al. Preparing and responding to 2019 novel coronavirus with simulation and technology-enhanced learning for healthcare professionals: challenges and opportunities in China. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn 2020;6:196–8. 10.1136/bmjstel-2020-000609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi GYS, Wan WTP, Chan AKM, et al. Preparedness for COVID-19: in situ simulation to enhance infection control systems in the intensive care unit. Br J Anaesth 2020;125:e236–9. 10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National virtual simulation experiment teaching sharing platform experiment space, 2019. Available: http://www.ilab-x.com/details/v4?id=4809&isView=true; [Accessed 30 Aug 2019].

- 28.Wang YL, Liu Y. The survey about the knowledge level of emergency treatment during the disasters among the emergency nurses and the countermeasures. Chinese J Pract Nurs 2006:47–69. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iqbal Z, Saleem K, Arshad HM. Measuring teachers’ knowledge of student assessment: Development and validation of an MCQ test. Educ Stud 2020;68. 10.1080/03055698.2020.1835615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Z, Sheng Y. An investigation of emergency nurses' preparedness for disasters in China. Chinese J Nurs 2014;49:699–703. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tichy MB, Renea B, Barbara H. Nurse practitioners' perception of disaster preparedness education. Am J Nurse Pract 2009;13:10–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Najafi Ghezeljeh T, Mohammad Aliha J, Haghani H, et al. Effect of education using the virtual social network on the knowledge and attitude of emergency nurses of disaster preparedness: a quasi-experiment study. Nurse Educ Today 2019;73:88–93. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyaw BM, Saxena N, Posadzki P, et al. Virtual reality for health professions education: systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e12959. 10.2196/12959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparkes L, Chan MMK, Cooper S, et al. Enhancing the management of deteriorating patients with Australian on line e-simulation software: acceptability, transferability, and impact in Hong Kong. Nurs Health Sci 2016;18:393–9. 10.1111/nhs.12282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derya Uzelli Yilmaz SHT, Yusuf Yilmaz. nursing education in the era of virtual reality 2020.

- 36.Labrague LJ, Hammad K, Gloe DS, et al. Disaster preparedness among nurses: a systematic review of literature. Int Nurs Rev 2018;65:41–53. 10.1111/inr.12369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khanal P, Vankipuram A, Ashby A, et al. Collaborative virtual reality based advanced cardiac life support training simulator using virtual reality principles. J Biomed Inform 2014;51:49–59. 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Youngblood P, Harter PM, Srivastava S, et al. Design, development, and evaluation of an online virtual emergency department for training trauma teams. Simul Healthc 2008;3:146–53. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31817bedf7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liaw SY, Ooi SW, Rusli KDB, et al. Nurse-Physician communication team training in virtual reality versus live simulations: randomized controlled trial on team communication and teamwork attitudes. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e17279. 10.2196/17279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verkuyl M, Lapum JL, St-Amant O, et al. Curricular uptake of virtual gaming simulation in nursing education. Nurse Educ Pract 2021;50:102967. 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.102967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harmon J, Pitt V, Summons P, et al. Use of artificial intelligence and virtual reality within clinical simulation for nursing pain education: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Today 2021;97:104700. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hauze SW, Hoyt HH, Frazee JP, et al. Enhancing nursing education through affordable and realistic Holographic mixed reality: the virtual standardized patient for clinical simulation. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019;1120:1–13. 10.1007/978-3-030-06070-1_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pertile D, Gallo G, Barra F, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on surgical residency programmes in Italy: a nationwide analysis on behalf of the Italian Polyspecialistic young surgeons Society (SPIGC). Updates Surg 2020;72:269–80. 10.1007/s13304-020-00811-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rutherford-Hemming T, Alfes CMJCSiN . The use of hospital-based simulation in nursing Education—A systematic review 2017.

- 45.Gasteiger N, van der Veer SN, Wilson P, et al. Upskilling health and care workers with augmented and virtual reality: protocol for a realist review to develop an evidence-informed programme theory. BMJ Open 2021;11:e050033. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abeer William VLV, John P. Traditional instruction versus virtual reality simulation: a comparative study of phlebotomy training among nursing students in Kuwait. Journal of Education and Practice 2016;7:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu Y, Zou Z, Chen X. The effects of vSIM for Nursing™ as a teaching strategy on fundamentals of nursing education in undergraduates. Clin Simul Nurs 2017;13:194–7. 10.1016/j.ecns.2017.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watson CM, Duval-Arnould JM, McCrory MC, et al. Simulated pediatric resuscitation use for personal protective equipment adherence measurement and training during the 2009 influenza (H1N1) pandemic. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2011;37:515–23. 10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37066-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ragazzoni L, Ingrassia PL, Echeverri L, et al. Virtual reality simulation training for Ebola deployment. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2015;9:543–6. 10.1017/dmp.2015.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McWilliams LA, Malecha A. Comparing intravenous insertion instructional methods with haptic simulators. Nurs Res Pract 2017;2017:4685157 10.1155/2017/4685157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung E-Y, Park DK, Lee YH, et al. Evaluation of practical exercises using an intravenous simulator incorporating virtual reality and haptics device technologies. Nurse Educ Today 2012;32:458–63. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mabry J, Lee E, Roberts T, et al. Virtual simulation to increase self-efficacy through deliberate practice. Nurse Educ 2020;45:202–5. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-048611supp001.pdf (87.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.