Abstract

Streptococcus suis (S. suis) is a zoonotic pathogen that primarily inhabits the upper respiratory tract of pigs. Therefore, pigs that carry these pathogens are the major source of infection. Most patients are infected through contact with live pigs or unprocessed pork products and eating uncooked pork. S. Suis mainly causes sepsis and meningitis. The disease has an insidious onset and rapid progress. The patient becomes critically ill and the mortality is high. In this case report, we described a rare case of S. suis isolated from a middle-aged woman in Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province, China, who did not have any contact with live pigs and had not eaten uncooked pork. S. Suis was isolated from both the patient’s blood and cerebrospinal fluid samples.

Keywords: Streptococcus suis, Zoonotic diseases, Meningitis, Septicemia

Introduction

Streptococcus suis (S. suis) is a zoonotic pathogen that causes infectious diseases such as meningitis, bacteremia, endocarditis, endophthalmitis, arthritis, and toxic shock in pigs and humans [1]. Human infections caused by this pathogen are rare, and infection with this pathogen usually presents with permanent deafness and endocarditis in the sequelae of meningitis [2]. Individuals who have close occupational or accidental contact with pigs or pork products and who consume undercooked or undercooked pork may be at higher risk of infection [3, 4]. A meta-analysis showed that 395 (61%) of 648 patients were exposed to pigs or pork, while other risk factors were less common [5]. In 1968, the first case of S. suis infection was reported in Denmark [6]. Since then, cases of the infection have been reported in more and more countries. Most cases have occurred in Southeast Asia, where pig farming is highly developed and hog density is high [7]. A study of S. suis meningitis showed that the pathogenic bacteria were isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in 66.7% of the cases, from blood in 50%, and both the CSF and blood in 25% [8]. Here, we describe a case of bacteremia and meningitis caused by S. suis in a 49-year-old woman without a history of live pig contact or eating raw pork in Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province, China. S. suis was detected in both the blood and CSF culture of the patient. We analyzed the patient’s medical history, microbiological diagnosis process, drug sensitivity test, and treatment process, and reviewed and discussed the relevant literature.

Case report

A 49-year-old, normally healthy woman suffered from fevers up to 39.3 °C without obvious incentive and no chills. Her fever was accompanied by headaches and tinnitus and she also experienced projectile vomiting 1–2 times a day. The patient had symptoms of joint pain in the right limb, but no stiffness in the limbs. She had fainted once during treatment at the local hospital, lasting for 10 h but had no recollection of the syncope. Four days later, she was referred to our hospital due to persistent fever and headaches. The patient was a rural woman with no specific medical history, who denied recent exposure to pigs or other animals or even occasional exposure. The patient also had no history of eating raw or undercooked pork. On admission, the patient had a body temperature of 37.9 °C, a pulse of 55 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 22 beats/min, and a blood pressure of 115/58 mmHg. A physical examination revealed signs of neck stiffness and meningeal irritation, but no hearing impairment. The patient’s pharynx was congested; there was no enlarged tonsils, no arrhythmia, and no pathological murmurs. A neurological examination showed that the patient was lucid and mentally alert, with normal muscular tension in her extremities and normal knee-tendon reflexes.

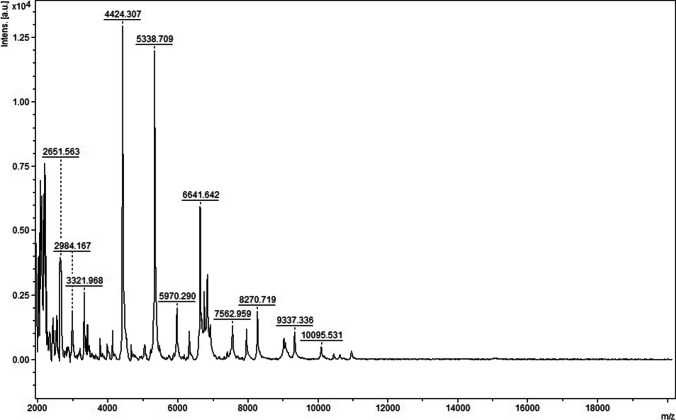

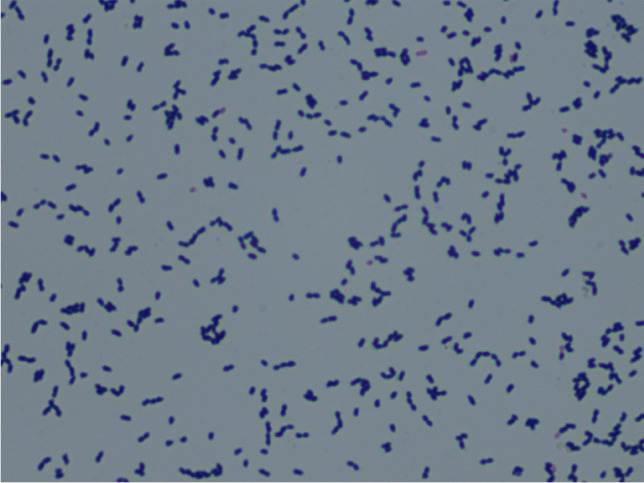

Routine laboratory examination and imaging examination indicated the following: leukocyte 14.63 × 109/L, neutrophils 89.1%, platelet 106 × 109/L, hemoglobin 119 g/L, C-reactive protein 32.8 mg/L, and procalcitonin 5.111 ng/ml. Tests for the NS1 antigen and IgM antibody of the dengue virus and nucleic acid and antibody (IgM and IgG) of the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) were all negative. Blood was drawn from both arms for blood culture (including aerobic and anaerobic cultures). CSF analysis demonstrated 968 leukocytes/μL with 84% polymorphonuclear cells, glucose 1.87 mmol/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 176 U/L, chloride 121 mmol/L, and protein 2587 mg/L. Gram stain of the CSF showed a few Gram-positive cocci, mostly in pairs (Fig. 1). Cryptococcus neoformans was not detected by Indian ink staining. A computed tomography scan of the patient’s head showed no abnormal findings.

Fig. 1.

A large number of neutrophils and a few Gram-positive cocci (green arrow) were found in the cerebrospinal fluid smear (Gram stain, × 1000)

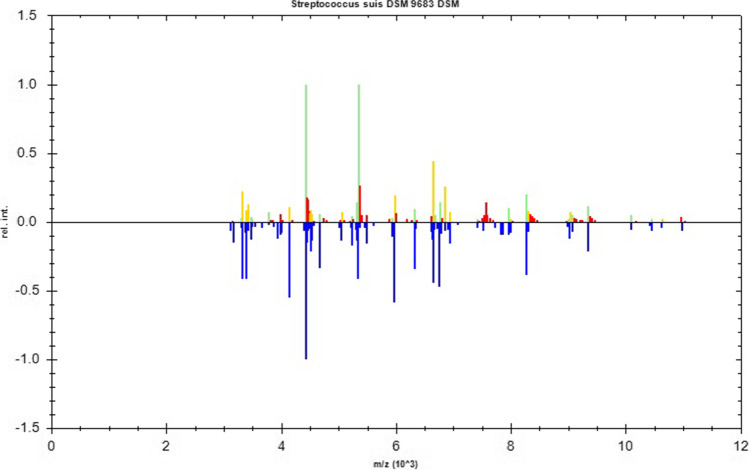

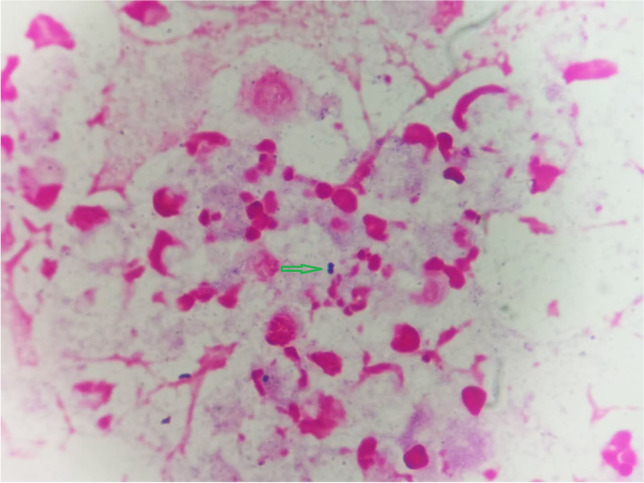

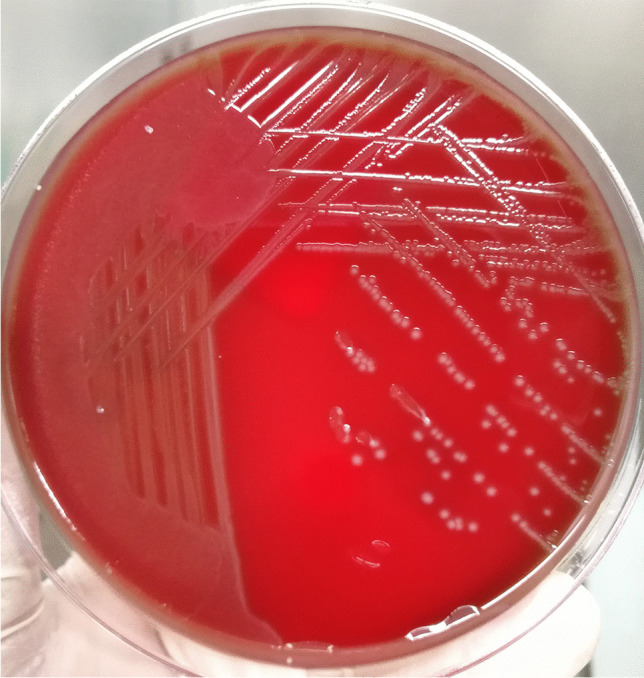

Two days later, four blood culture bottles, including two aerobic and two anaerobic bottles, presented positive and raised alarms. The positive specimens were transferred to blood agar plates for further culturing. The next day, α-hemolytic colonies grew on the sheep blood agar plates (Fig. 2). The organisms, which were Gram-positive cocci in chains (Fig. 3), were catalase-negative and were identified as S. suis using the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometer (Bruker Inc., Germany) with 2.303 log-score (according to the instruction manual of the instrument, higher than 2.300 of the score implies “highly probable species identification”) (Figs. 4 and 5). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by E-test method for penicillin G and meropenem and disk diffusion method for other antibiotics according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100-S30 guidelines [9]. Susceptibility test results revealed that the bacterium was sensitive to penicillin G, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, meropenem, levofloxacin, linezolid, chloramphenicol, and vancomycin but resistant to clindamycin and erythromycin. The results of identification and antimicrobial sensitivity of the bacteria isolated from CSF were consistent with those from the blood cultures.

Fig. 2.

Streptococcus suis showed α-hemolysis, medium size, gray white, smooth, and moist colonies on the sheep blood agar

Fig. 3.

Under the microscope, the cultured Streptococcus suis appeared as Gram-positive cocci with double or broken chains (Gram stain, × 1000)

Fig. 4.

A mass spectrum of Streptococcus suis

Fig. 5.

A comparison chart between the mass spectrum of the measured strain and that of the database

Before the isolation of S. suis, ceftriaxone and meropenem were administered intravenously for empirical treatment. After the pathogen and drug sensitivity were confirmed, ceftriaxone and penicillin were used for definitive treatment. At the same time, mannitol was used to reduce intracranial pressure, gamma globulin was used to strengthen immunity, and mecobalamin was used to nourish the nerves. One week after the patient was admitted for treatment, routine and biochemical examinations of CSF and blood were conducted. The CSF and culture results returned to normal. The patient was discharged after completion of a 14-day course of oral antibiotic therapy. Her symptoms, except tinnitus, improved.

Discussion

S. suis is a Gram-positive facultative anaerobe with capsule structure, which can be classified as Lancefield group D Streptococcus according to its cell wall antigen composition [10]. S. suis can colonize the upper respiratory (especially nasal cavity and tonsils), genital, and digestive tracts in healthy swines. Zhang collected 1813 nasal cavity samples from healthy pigs raised on 17 independent farms in six Chinese provinces between 2016 and 2018 and obtained 223 S. suis isolates (12.3%) [11]. S. suis can survive in the dust, fertilizer, and pig carcasses for days or even weeks under suitable conditions. Therefore, the surrounding environment of hoggeries and slaughterhouses may be a source of human S. suis infection [12]. Owing to the limitation of the living environment of S. suis, the infection cases caused by the pathogens are rare and typically sporadic. The particular occupational groups who have a history of close contact with pigs or raw pork, such as pig breeders, veterinarians, meat processing workers, transport workers, butchers, and cooks, are at high risk of S. suis infection and account for the vast majority of cases. When they suffer from skin damage, even minor and invisible damage, and expose to pigs and raw pork carrying S. suis, the pathogens can enter the human bloodstream directly and cause infection [13].

However, sometimes the infection route of S. suis is not clear. Some patients who have not contacted animal or pork products have been reported to have been infected by S. suis [14–16]. Therefore, it can be inferred that there are other ways of human infection with S. suis. A recent study showed that the gastrointestinal tract is an entry site for S. suis, supporting the epidemiological evidence that ingestion of S. suis–contaminated food is a risk factor for infection [17, 18]. In addition, as reported previously for Group B Streptococcus, diabetes mellitus, splenectomy, alcoholism, and malignancies have been considered to be important predisposing factors for severe, rapidly progressing, and ultimately fatal S. suis infection [13, 19]. In current case, the patient is a healthy rural woman, who had no history of contact with live pigs or eating raw pork. The infection of S. suis may have been caused by contact with pork contaminated with S. suis during cooking.

Meningitis is the most common clinical manifestation of S. suis infection, and its symptoms are similar to those of other types of bacterial suppurative meningitis. Sepsis is considered to be the second most common manifestation and the leading cause of S. suis–related death [20]. S. suis was detected in both the CSF and blood samples of this patient, indicating that the patient suffered from meningitis and bacteremia caused by S. suis. Therefore, such a case is relatively rare. The important sign of S. suis pathogenicity is its capability of extensive circulation in the bloodstream and maintain a state of bacteremia for a period of time, leading to the occurrence of meningitis [21]. However, little is known about the mechanism of S. suis invading the human body and crossing the blood–brain barrier.

S. suis showed α-hemolysis on sheep blood plates which can easily be misdiagnosed as other common Streptococcus species. Consequently, identification of S. suis is sometimes difficult because it is frequently misidentified as S. acidominimus or S. vestibularis by the Phoenix System or as S. sanguinis by the Vitek II System [22, 23]. Misidentification of the microbes may lead to a failure to correctly diagnose the S. suis infection. Therefore, the suspicious strains isolated from patient with epidemiological history should be identified by 16S rRNA sequencing or MALDI-TOF–MS to avoid a missed detection of S. suis, especially in areas with a high prevalence of S. suis diseases. In the present case, S. suis was identified by mass spectrometry with a high log-score, indicating that the identification result is reliable.

S. suis is sensitive to penicillin or cephalosporin. High-dose intravenous penicillin G is very effective in most patients. Resistance to tetracycline and macrocyclic vinegar is common but there are few cases of multi-drug resistance. Biofilm formation likely contributes to the virulence and drug resistance in S. suis [24]. For this patient, ceftriaxone and meropenem were used for empirical treatment before confirming the pathogen’s identification. After the identification of S. suis and drug sensitivity results, ceftriaxone and penicillin were used for targeted treatment. The treatment effect was obvious.

Deafness is a distinct sequela (50.5% in Europe and 51.9% in Asia) after recovery from S. suis infection, especially in patients with meningitis [25]. When S. suis is confirmed as the pathogen of suppurative meningitis, the treatment regimen should be adjusted to avoid exposure to potential ototoxic antibiotics and corticosteroids in order to prevent and reduce the incidence of deafness complications. It is also an important measure to reduce the incidence of hearing loss and neurological sequelae by bringing all patients with S. suis infection into the management of multidisciplinary teams, including otolaryngologists [26]. In addition, due to the lack of experience in this zoonotic disease and the difficulty of the microbiological diagnosis, a complete review is necessary to obtain key information and guide the clinical diagnosis of this infection [5, 27].

Author contribution

Yijun Zhu contributed to the study conception and design and drafted the manuscript; Fang Zhu revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; Lihong Bo and Yinfei Fang performed the main part of the data collection; and Xiaoyun Shan provided help with analysis and interpretation of the patient’s data.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinhua Central Hospital (No. 2020–150).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from individual or guardian participants.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Responsible Editor: Jorge Luiz Mello Sampaio

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Núñez JM, Marcotullio M, Rojas A, Acuña L, Cáceres M, Mochi S. Primer caso de meningitis por Streptococcus suis en el noroeste de Argentina [First case of meningitis by Streptococcus suis in the northwest area of Argentina] Rev Chilena Infectol. 2013;30:554–556. doi: 10.4067/S0716-10182013000500014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai HC, Lee SS, Wann SR, Huang TS, Chen YS, Liu YC. Streptococcus suis meningitis with ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection and spondylodiscitis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104(12):948–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zalas-Więcek P, Michalska A, Grąbczewska E, Olczak A, Pawłowska M, Gospodarek E. Human meningitis caused by Streptococcus suis. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62(Pt 3):483–485. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.046599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeuchi D, Kerdsin A, Akeda Y, Chiranairadul P, Loetthong P, Tanburawong N, et al. Impact of a food safety campaign on Streptococcus suis infection in humans in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:1370–1377. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Samkar A, Brouwer MC, Schultsz C, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Streptococcus suis meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perch B, Kristjansen P, Skadhauge K. Group R streptococci pathogenic for man. Two cases of meningitis and one fatal case of sepsis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1968;74:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1968.tb03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim H, Lee SH, Moon HW, Kim JY, Lee SH, Hur M, et al. Streptococcus suis causes septic arthritis and bacteremia: phenotypic characterization and molecular confirmation. Korean J Lab Med. 2011;31:115–117. doi: 10.3343/kjlm.2011.31.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suankratay C, Intalapaporn P, Nunthapisud P, Arunyingmongkol K, Wilde H. Streptococcus suis meningitis in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35:868–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (2020) Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; Thirtieth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S30. CLSI, Wayne

- 10.Yanase T, Morii D, Kamio S, Nishimura A, Fukao E, Inose Y, et al. The first report of human meningitis and pyogenic ventriculitis caused by Streptococcus suis: a case report. J Infect Chemother. 2018;2018(24):669–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, Zhang P, Wang Y, Fu L, Liu L, Xu D, et al. Capsular serotypes, antimicrobial susceptibility, and the presence of transferable oxazolidinone resistance genes in Streptococcus suis isolated from healthy pigs in China. Vet Microbiol. 2020;247:108750. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottschalk M, Xu J, Calzas C, Segura M. Streptococcus suis: a new emerging or an old neglected zoonotic pathogen? Future Microbiol. 2010;5:371–391. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ágoston Z, Terhes G, Hannauer P, Gajdács M, Urbán E. Fatal case of bacteremia caused by Streptococcus suis in a splenectomized man and a review of the European literature. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2020;67:148–155. doi: 10.1556/030.2020.01123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidalgo A, Ropero F, Palacios R, García V, Santos J. Meningitis due to Streptococcus suis with no contact with pigs or porcine products. J Infect. 2007;55:478. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galbarro J, Franco-Alvarez de Luna F, Cano R, Angel Castaño M. Meningitis aguda y espondilodiscitis por Streptococcus suis en paciente sin contacto previo con cerdos o productos porcinos derivados [Acute meningitis and spondylodiscitis due to Streptococcus suis in a patient who had no contact with pigs or porcine products] Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2009;27:425–427. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manzin A, Palmieri C, Serra C, Saddi B, Princivalli MS, Loi G, et al. Streptococcus suis meningitis without history of animal contact, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1946–1948. doi: 10.3201/eid1412.080679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrando ML, de Greeff A, van Rooijen WJ, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Nielsen J, WichgersSchreur PJ, et al. Host-pathogen interaction at the intestinal mucosa correlates with zoonotic potential of Streptococcus suis. J Infect Dis. 2014;212:95–105. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huong VT, Ha N, Huy NT, Horby P, Nghia HD, Thiem VD, et al. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and outcomes of Streptococcus suis infection in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1105–1114. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.131594.PMID:24959701;PMCID:PMC4073838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aspiroz C, Vela AI, Pascual MS, Aldea MJ. Endocarditis aguda por Streptococcus suis serogrupo 2 en España [Acute infective endocarditis due to Streptococcus suis serotype 2 in Spain] Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2009;27:370–371. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi SM, Cho BH, Choi KH, Nam TS, Kim JT, Park MS, et al. Meningitis caused by Streptococcus suis: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Neurol. 2012;8:79–82. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2012.8.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katayama M, Mori T, Hasegawa S, Kanakubo Y, Shimizu A, Hayano S, et al. New technology meets clinical knowledge: diagnosing Streptococcus suis meningitis in a 67-year-old man. IDCases. 2018;12:119–120. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen FL, Hsueh PR, Ou TY, Hsieh TC, Lee WS. A cluster of Streptococcus suis meningitis in a family who traveled to Taiwan from Southern Vietnam. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49:468–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Susilawathi NM, Tarini NMA, Fatmawati NND, Mayura PIB, Suryapraba AAA, Subrata M, et al. Streptococcus suis-associated meningitis, Bali, Indonesia, 2014–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:2235–2242. doi: 10.3201/eid2512.181709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi L, Jin M, Li J, Grenier D, Wang Y. Antibiotic resistance related to biofilm formation in Streptococcus suis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:8649–8660. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10873-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang YT, Teng LJ, Ho SW, Hsueh PR. Streptococcus suis infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2005;38:306–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hlebowicz M, Jakubowski P, Smiatacz T. Streptococcus suis meningitis: epidemiology, clinical presentation and treatment. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019;19:557–562. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2018.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jover-García J, López-Millán C, Gil-Tomás JJ. Emerging infectious diseases: Streptococcus suis meningitis. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2020;33:385–386. doi: 10.37201/req/055.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.