Abstract

Objectives

Self-compassion-focused interventions may be able to decrease posttraumatic stress symptoms. However, previous studies demonstrated mixed effects in which a series of confounders were not systematically quantified. In this study, a systematic review with meta-analysis was conducted to quantify the effects of self-compassion-focused therapies on posttraumatic stress disorder.

Methods

Twelve eligible studies were included after a systematic search of databases. Outcome measures were extracted for posttraumatic stress disorder.

Results

Our data indicated a medium protective effect on posttraumatic stress symptoms (SMD = − 0.65), with most of the studies (8/12) coming from clinical settings. More importantly, longer interventions were associated with better posttraumatic stress outcomes (p < 0.001). Baseline or changes in self-compassion scores were not associated with posttraumatic stress outcomes post-interventions.

Conclusions

Overall, findings from this meta-analysis quantified the complex influence of self-compassion-focused interventions on posttraumatic stress symptoms and may provide insights for optimizing intervention strategies.

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Registration: PROSPERO CRD42020208663.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12671-021-01732-3.

Keywords: Self-compassion, Intervention, PTSD, Posttraumatic stress, Meta-analysis

Self-compassion is described as the ability to be kind and caring to one’s own sufferings, understand them with no judgment, and treat these sufferings as a shared human experience (Neff, 2003). Self-compassion-focused interventions were defined as programs with a primary focus on cultivating compassion toward oneself (Kirby & Gilbert, 2019). Indeed, self-compassion-focused interventions have been increasingly employed in the context of overall well-being. Self-compassion interventions were demonstrated to be able to improve health behavior, eating pathology, and body image (Phillips & Hine, 2019; Turk & Waller, 2020). Moreover, self-compassion-focused interventions improved a variety of psychosocial outcomes, such as stress, depression, self-criticism, and anxiety (Cȃndea & Szentágotai-Tătar, 2018; Ferrari et al., 2019; Neff & Germer, 2013).

Self-compassionate individuals tend to treat themselves with kindness, acceptance, and a sense of common humanity and may engage in less self-blaming and avoidance behaviors following trauma exposure (Hamrick & Owens, 2019; Thompson & Waltz, 2008). Moreover, compassion is believed to be able to activate self-regulating and soothing functioning, which can help modulate a hyperactive threat system that is often related to posttraumatic stress symptoms (Hoffart et al., 2015; Lee & James, 2013; Rockliff et al., 2008).

Recent studies highlight the potential of self-compassion-focused interventions in the management of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Serpa et al., 2021; Winders et al., 2020), which occurs following exposure to severe accidents, for example, actual or threatened death, domestic violence, war, or natural disaster (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, studies have demonstrated mixed effects and it is important to optimize the benefits of self-compassion-focused interventions on PTSD. Distinct effects may be associated with variances in self-compassion protocols. Randomized controlled designs are critical to interventions and it is noted that studies varied in terms of the presence of a control group. Study participants have varied, which included clinical (i.e., individuals with a previous diagnosis) or nonclinical samples (i.e., the general populations without a clinical diagnosis, such as postpartum mothers and college students) (Hwang & Chan, 2019; Mitchell et al., 2018). A recent study supported the efficacy of self-compassion interventions across diverse populations (Ferrari et al., 2019). Moreover, the literature varied in the number of sessions from four to twelve (Au et al., 2017; Evans et al., 2019; Grodin et al., 2019; Held & Owens, 2015). Studies have demonstrated that the efficacy of self-compassion-focused therapies is shaped by the number of training session (Phillips & Hine, 2019; Wakelin et al., 2021). Other factors may as well play a role in intervention outcomes, such as the way of delivering interventions (e.g., group-based class or self-administration). It is therefore important to characterize and quantify these confounders in a systematic fashion with meta-analysis.

The current meta-analytic study was designed to explore the complex effects of self-compassion-focused approaches on PTSD symptoms. Potential confounders were, therefore, carefully examined in this context. We also assessed the changes in self-compassion score which is supposed to be closely associated with intervention outcomes (Bistricky et al., 2017; Valdez & Lilly, 2016; Zeller et al., 2015). Overall, findings from this meta-analysis may help to quantify the complex influence of self-compassion-focused interventions on PTSD symptoms and therefore provide insights for optimizing intervention strategies.

Methods

Identification and Selection of Studies

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2009). A comprehensive literature search was carried out (up to September 2020 with no limit on starting date) in PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. The search terms used were (“PTSD” OR “posttraumatic stress”) AND (“self-compassion” OR “self-compassionate” OR “compassion” OR “self-warmth” OR “self-kindness”) (see Supplementary Material S1 for full search records).

After removing duplicates, the title, and abstract of searching results were screened by two reviewers (XL and XC) independently against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full texts were examined if it was unclear whether the studies met selection criteria. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were then carefully screened. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus. Reference lists of potentially eligible studies were manually checked.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they matched all five a priori criteria: studies were included if (1) they conducted an intervention with a primary focus on self-compassion but were excluded if studies didn’t use an explicit self-compassion intervention; (2) they made comparisons before and after the intervention but were excluded if there was no baseline measurement; (3) they reported symptoms of PTSD but were excluded if they did not measure PTSD; (4) sufficient data were provided to calculate effect size (i.e., sample size, mean, and standard deviation) but were excluded if data were not available; (5) they were written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals (see Supplementary Material Table 1).

Data Extraction

Outcome data from eligible studies (means, standard deviations, and sample sizes) were extracted for PTSD symptoms and self-compassion scores. Data were extracted from relevant figures using PlotDigitizer software if numerical values were not directly available (Huwaldt, 2010). We contacted the corresponding authors for additional data when they could not be extracted from articles directly. It is noted that one included study (Lang et al., 2020) reported F value of change scores, the variance of post-intervention was therefore imputed from another study using the same outcome measure according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Wells, 2011).

Quality Assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) assessment tool for quantitative studies (Thomas et al., 2004). Specifically, the criteria (strong/moderate/weak) were selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, and attrition. Each study was given an overall score based on the number of weak component ratings. The EPHPP has good construct validity and inter-rater reliability (Thomas et al., 2004). Two reviewers (XL and XC) independently assessed the quality of included studies with a good inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s kappa = 0.73). In cases of initial disagreements on a certain item, the two reviewers discussed them, and finally, an agreement was achieved.

Data Analyses

Meta-analyses were conducted using the MIX 2.0 computer program (Bax, 2011), which calculated the statistical significance of differences between means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The effect size was calculated using Hedge’s adjusted g based on the standardized mean difference (SMD). Hedge’s adjusted g is similar to Cohen’s d, but it adjusts for biases due to small sample sizes (Hedges & Olkin, 2014). For SMDs, effect sizes ≥ 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were considered small, medium, and large, respectively (Cohen, 1988).

Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the main and interaction effect between self-compassion interventions and participants’ clinical status. The classification of clinical status was based on screening results of participants from included studies. As the number of sessions and reported self-compassion may modulate the efficacy of self-compassion-focused interventions (Galili-Weinstock et al., 2018; Phillips & Hine, 2019), they were further investigated as potential moderators.

In this meta-analysis, heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic and Galbraith plot (Higgins et al., 2003; Thompson, 1994). Random-effect models were used which allows for statistical control of heterogeneity and generalization of meta-analytic results. Different methodologies were used to examine publication bias (Che et al., 2018). The selectivity funnel plot, Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlations, Egger’s regression intercept test, and a Bayesian approach were carried out (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994; Egger et al., 1997; Guan & Vandekerckhove, 2016) (see details in Supplementary Material S2).

Results

Study Selection

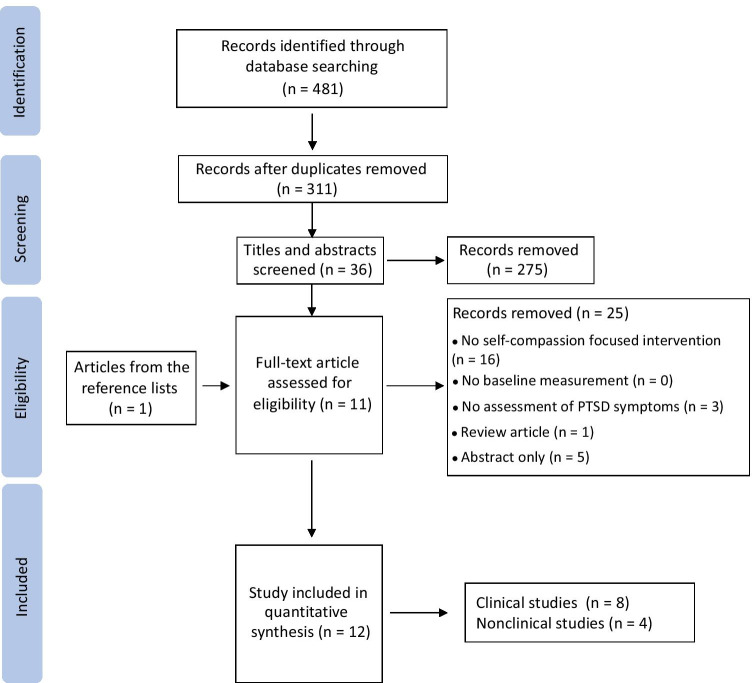

The online database search identified a total of 481 records (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 311 studies remained. Title and abstract screening resulted in 36 studies for full-text assessment. Finally, a total of twelve studies, including one from reference lists, were included in the review and meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of included studies (n = number of articles)

Study Characteristics

An overview of the characteristics of the included studies is presented in Table 1. The sample sizes ranged from 10 to 75, with one study recruited 262 participants. Eight studies were conducted among PTSD patient groups with the remaining in nonclinical samples. The study populations ranged from veterans (n = 6) and undergraduate students (n = 2) to trauma-exposed adults with shame (n = 1), survivors of interpersonal violence (n = 1), postpartum mothers (n = 1), and intensive outpatients (n = 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author, year | Population (N) | Age (range) | Gender ratio (M:F) | Pre-diagPTSDa | Intervention | Session number | Control group | PTSD Measure | Self-compassion Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au et al., 2017 | Trauma-exposed adults (N = 10) | (18–32) | 1:8 (1 nonbinary) | N | A brief compassion-based therapy, 6 weeks | 6 | PCL-5 | SCS | |

| Evans et al., 2019 | Veterans (N = 12) | (31–69) | 12:0 | Y | Cognitively-based compassion training (CBCT), 10 weeks | 10 | PCL | ||

| Grodin et al., 2019 | Veterans (N = 22) | 52.6 ± 12.9 | 21:0 | Y | Compassion-focused therapy (CFT), 12 weeks | 12 | PCL-5 | SCS | |

| Held & Owens, 2015 | Homeless male veterans (N = 27) | (33–64) | 27:0 | Y | Self-compassion workbook training, 4 weeks | 4 | Stress inoculation | PCL-S | SCS |

| Held et al., 2018 | Intensive outpatients (N = 19) | (21–54) | 13:6 | Y | Brief self-compassion training (BSCT), 4 weeks | 4 | PCL-5 | SCS | |

| Hwang & Chan, 2019 | College students with racial stress (N = 10) | n/a | 2:7 (1 other) | N | Compassionate meditation program, 8 weeks | 8 | PCL-5 | SCS | |

| Kearney et al., 2013 | Veterans (N = 42) | n/a | 25:17 | Y | Loving-kindness meditation course, 12 weeks | 12 | PSS-1 | SCS | |

| Lang et al., 2019 | Veterans (N = 28) | 49.1 ± 14.5 | 3:1 | Y | Cognitively based compassion training (CBCT), 10 weeks | 10 | Veteran.calm (VC) | CAPS-5 | SCS-SF |

| Lang et al., 2020 | Veterans (N = 31) | 43.9 ± 12.6 | 29:2 | Y | Cognitively based compassion training (CBCT), 10 weeks | 10 | PCL-5 | SCS-SF | |

| Lee et al., 2017 | Survivors of interpersonal violence (N = 63) | (22–56) | 0:58 | Y | Breathing, loving-kindness, and compassion meditation, 6 weeks | 6 | Control condition | MPSS | |

| Mitchell et al., 2018 | Post-partum mothers (N = 262) | (18–44) | 0:262 | N | Brief online self-compassion intervention, 4 weeks | 4 | IES-R | SCS-SF | |

| Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019 | College students with problematic alcohol use (N = 75) | 19.2 ± 1.3 | 23:52 | N | Group loving–kindness meditation, 4 weeks | 4 | Referral to treatment as usual (RTAU) | PCL-5 |

Note. M, male; F, female; PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PCL, PTSD Checklist; PCL-S, PTSD Checklist–Specific Stressor Version; PSS-1, PTSD Symptom Scale Interview; CAPS-5, Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; MPSS, the Modified PTSD Symptom Scale; IES-R, The Impact of Events Scale-Revised; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; SCS-SF, Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form

aY, participants in the study were previously diagnosed with PTSD; N, participants without a previous diagnosis of PTSD

A variety of designs were identified in the included studies, such as multiple baseline design (Au et al., 2017), randomized controlled trial (Lang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2017; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019) and uncontrolled pre-post design (Mitchell et al., 2018). Most of the studies were uncontrolled (n = 8), with only four studies including a control group.

A variety of self-compassion-focused treatments were conducted, including online self-compassion intervention, self-compassion workbook training, compassion-focused therapy, cognitively-based compassion training, and loving-kindness meditation. Of the twelve intervention studies, ten were delivered in a group format in the presence of a therapist or a leader and two were delivered individually.

Quality Assessment

Quality varied across included studies (Table 2, Supplementary Material Fig. 1). Two studies were rated as strong quality, six were rated as moderate, and four were rated as weak. The major strength was data collection as a reliable measure was used, such as PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Attrition assessment showed moderate to strong evidence whereby most of the participants finished the intervention and completed the pre- and post- assessments. Blinding was a limitation in these studies, with some of the included studies (n = 5) failed to indicate whether outcome assessors were aware of intervention status or group allocation. The included studies were also limited by selection bias, in which several studies (n = 5) were conducted among male veterans.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies using the EPHPP tool

| Author, year | Component rating | Overall rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection method | Attrition | ||

| Au et al., 2017 | W | S | M | M | M | S | Moderate |

| Evans et al., 2019 | W | W | M | W | M | S | Weak |

| Grodin et al., 2019 | M | W | M | M | M | M | Moderate |

| Held & Owens, 2015 | M | S | W | W | S | W | Weak |

| Held et al., 2018 | M | W | M | M | S | S | Moderate |

| Hwang & Chan, 2019 | W | W | W | W | S | M | Weak |

| Kearney et al., 2013 | M | W | M | M | M | S | Moderate |

| Lang et al., 2019 | M | S | M | W | M | M | Moderate |

| Lang et al., 2020 | M | M | M | M | W | S | Moderate |

| Lee et al., 2017 | M | S | M | M | M | M | Strong |

| Mitchell et al., 2018 | M | W | W | W | M | M | Weak |

| Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019 | M | S | M | M | S | M | Strong |

Note: EPHPP denotes the Effective Public Health Practice Project. S, strong, no weak component rating; M, moderate, one weak component rating; W, weak, two or more weak component ratings

Meta-Analysis of Effects of Self-Compassion Focused Interventions on PTSD

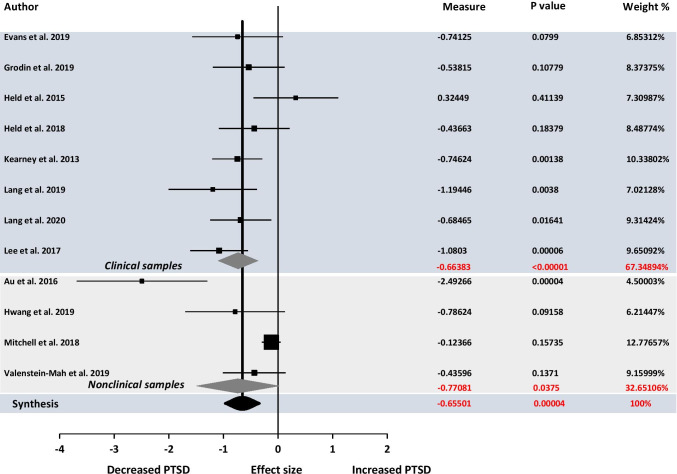

Data extracted from all studies were pooled initially. Overall, self-compassion-focused interventions revealed a moderate effect on PTSD symptoms (SMD = − 0.65, 95%CI: [− 0.97, − 0.34], p = 0.00004) (Fig. 2), suggesting that self-compassion-focused interventions decreased PTSD symptoms from baseline to post-intervention.

Fig. 2.

Forrest plot of the Hegde’s adjusted g analysis for effects of self-compassion focused interventions on PTSD. Data were presented separately among clinical and nonclinical populations

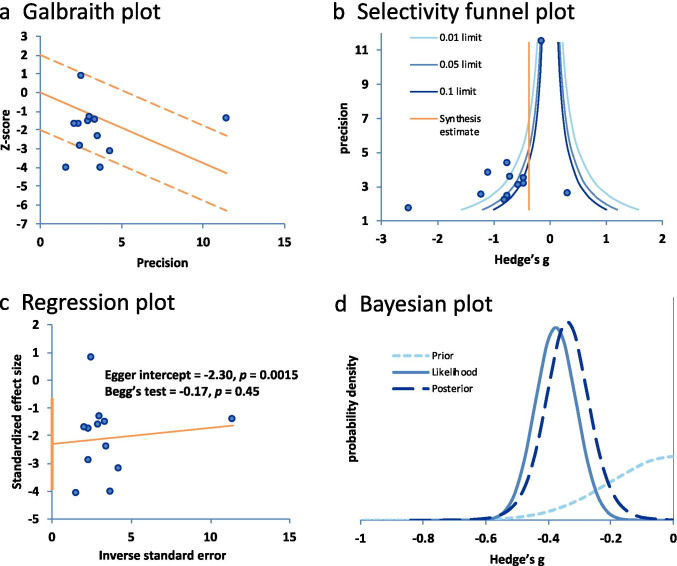

Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

Galbraith plot indicated heterogeneity in the dataset as more than 5% of the studies locating beyond two standard errors of the population effect (Fig. 3a). The statistical test also indicated heterogeneity (Q = 39.84, p = 0.00004, I2 = 72.39%). The shape of the selectivity funnel plot indicated asymmetry (Fig. 3b), with each line in the plot suggesting different levels of significance (0.01, 0.05, and 0.1). Egger’s regression test (t = − 2.30, p = 0.0015) but not Begg’s test (tau = − 0.17, p = 0.45) demonstrated publication bias (Fig. 3c). Additionally, the Bayesian analysis indicated publication bias with the likelihood effect size (− 0.38) much smaller than the estimated effect size (− 0.66) (Fig. 3d). Overall, these analyses suggested the presence of publication bias in the dataset.

Fig. 3.

Series of tests for heterogeneity and publication bias for effects of self-compassion focused interventions on PTSD. (a) Galbraith plot suggested heterogeneity with more than 5% of the data beyond two stand errors of the population. (b) Selectivity funnel plot indicated publication bias. (c) Egger’s test but not Begg’s test suggested publication bias. (d) Bayesian plot indicated publication bias with the likelihood effect size (− 0.38) much smaller than the estimated effect size (− 0.66)

Subgroup Analyses on PTSD

Self-compassion focused interventions demonstrated a medium effect on PTSD in both clinical (SMD = − 0.66, 95%CI: [− 0.95, − 0.38], p < 0.00001) and nonclinical samples (SMD = − 0.77, 95%CI: [− 1.50, − 0.04], p = 0.038). This protective effect was dominated by clinical studies (8/12 studies) (Fig. 2).

Only four studies included a control group (Held & Owens, 2015; Lang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2017; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019). Among these four studies, self-compassion-focused interventions showed no effect on PTSD (SMD = − 0.61, 95%CI: [− 1.24, 0.02], p = 0.06). However, one study conducted an intervention in the absence of a therapist (Held & Owens, 2015). After removing this study, our data further demonstrated a large effect on PTSD (SMD = − 0.87, 95%CI: [− 1.34, − 0.40], p = 0.0003) (see Supplementary Material Fig. 2).

After removing studies with weak quality, self-compassion-focused training demonstrated a large effect on PTSD outcomes (SMD = − 0.82, 95%CI: [− 1.12, − 0.51], p < 0.00001) (see Supplementary Material Fig. 3).

Meta-regression indicated that session number had an effect on intervention outcomes (p < 0.001), suggesting that longer interventions were associated with better PTSD outcomes. Moreover, either baseline or change scores of reported self-compassion had no impact on intervention effects (see Supplementary Material Fig. 4).

Meta-Analysis of Effects of Self-Compassion Focused Interventions on Self-Compassion

Meta-analysis revealed no effect of self-compassion-focused training on self-compassion scores (SMD = 0.32, 95%CI: [− 0.11, 0.76], p = 0.14). Self-compassion interventions demonstrated a small effect on self-compassion in clinical (SMD = 0.44, 95%CI: [0.12, 0.77], p = 0.008) but no effect in nonclinical populations (SMD = 0.28, 95%CI: [− 1.23, 1.79], p = 0.72) (see Supplementary Material Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study was designed to quantify the complex influence of self-compassion-focused interventions on PTSD symptoms. A total of twelve studies were included. Our results indicated that self-compassion-focused interventions had an overall medium protective effect on PTSD symptoms. These effects were dominated by findings from clinical populations. More importantly, longer interventions were found to be associated with better PTSD outcomes. Finally, baseline or changes in self-compassion scores did not affect PTSD outcomes post-interventions.

The synthesis revealed a medium protective effect of self-compassion-focused therapies on PTSD symptoms. Previous reviews have identified a positive relationship between self-compassion and well-being (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; Turk & Waller, 2020; Winders et al., 2020). Our study further quantified intervention-based PTSD outcomes and included seven more latest trials (Evans et al., 2019; Grodin et al., 2019; Hwang & Chan, 2019; Lang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2018; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019). It is noted that most of the included studies (8/12) did not have a control group. We, therefore, further quantified the intervention effects in controlled designs (Held & Owens, 2015; Lang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2017; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019). These findings, therefore, confirmed the therapeutic applications of self-compassion-focused interventions in managing PTSD symptoms.

More importantly, the protective effect of self-compassion-focused interventions was dominated by findings from clinical populations which therefore has direct clinical implications (Fig. 2). In an RCT study, clients in the compassion group had significant changes in trauma symptoms and mental health symptoms (Lee et al., 2017). Similarly, a more substantive reduction in PTSD symptoms was observed in the compassion group than in the control condition (Lang et al., 2019). In another study, 43.2% of veterans had a reliable change in PTSD symptoms at a 3-month follow-up (Kearney et al., 2013). Our synthesis, therefore, provides direct evidence for self-compassion-focused interventions in managing PTSD symptoms.

Self-compassion-focused interventions with more sessions may allow for skill consolidation and thus creating an enduring effect on posttraumatic stress syndrome. Our data supported this argument in which longer interventions were associated with better PTSD outcomes. Our pooled dataset identified session numbers ranging from four to twelve. There is not enough evidence to determine the optimal session number in the management of PTSD. Our pooled dataset indicated that five sessions or more could achieve an effect size of 0.5 or even higher (see Supplementary Material Fig. 4a). Instead, session number below five showed inconsistent efficacy. Future studies may wish to identify the optimal session number in the management of PTSD.

Findings from meta-regression indicated that baseline or changes in self-compassion scores may not affect PTSD outcomes post-intervention. It is possible that self-compassion-focused interventions have the potential to buffer traumatic stress through other processes rather than self-compassion. Indeed, a recent controlled trial demonstrated that compassion meditation reduced PTSD symptoms through social connectedness and empathy, but not self-compassion (Lang et al., 2019). Similarly, individuals benefited from self-compassion by better utilizing social support and social connections in coping with traumatic experiences (Kok et al., 2013; Litz & Carney, 2018; Maheux & Price, 2016). In the context of stress and health, a series of studies have demonstrated the role of adaptive coping strategies in mediating the influence of self-compassion on mental health, such as positive reframing and emotion regulation (Allen & Leary, 2010; Diedrich et al., 2017; Inwood & Ferrari, 2018; Sirois et al., 2015). In contrast, lower level of self-compassion was demonstrated to affect PTSD symptoms through emotion regulation difficulties and disengagement coping (Barlow et al., 2017; Hamrick & Owens, 2019; Lenferink et al., 2017; Scoglio et al., 2018). In addition, there is evidence suggesting physiological changes and neural activations associated with self-compassion (Liu et al., 2020; Luo et al., , 2018, 2020; Lutz et al., 2020).

It is unclear whether self-compassion-focused interventions could induce long-lasting benefits on PTSD symptoms. We did not evaluate the follow-up effects as only two studies reported midterm follow-up and one study reported long-term assessment (Au et al., 2017; Kearney et al., 2013; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019). Kearney and colleagues (Kearney et al. 2013) found a large effect on PTSD at post-test and 3-month follow-up. A multiple baseline study found all participants to improve in PTSD symptoms at post-test and 1-month follow-up (Au et al., 2017). However, the active and control group were not different in the reduction of PTSD symptoms in another study (Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019). These studies highlighted the importance of evaluating longer-term effects in self-compassion-focused interventions.

Subgroup analysis further provided partial evidence suggesting the importance of a therapist for self-compassion-focused interventions (see Supplementary Material Fig. 2). The presence of a therapist is believed to be important for the participants to keep up with the interventions and to improve learning efficacy (Lawrence & Lee, 2014). However, this finding needs to be validated in future studies. Moreover, our data did not erase the significance of online training which were convenient and economical (Mitchell et al., 2018). Online training with a therapist may be an optimal and effective option in some cases, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic or in rural areas (González-García et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021).

The effect of self-compassion-focused interventions on PTSD was characterized by a medium level of heterogeneity. The present synthesis included PTSD from varied populations with different types of traumas (e.g., war, interpersonal violence, racial stress). Follow-up analysis showed larger effect sizes in RCTs and studies with moderate to strong quality, indicating the need for strictly controlled studies. Moreover, the way of delivering interventions (e.g., group-based class or self-learning), as well as study populations (clinical vs. nonclinical populations) may play a role in outcomes. Meta-regression further identified session number as a potential moderator, suggesting the need for longer interventions.

The presence of risk of bias can affect the results of a meta-analysis. Our data indicated that 67% of the included studies demonstrated moderate to strong quality. Some studies adopted a randomized control design, and an overall low level of drop-out rate was reported. The outcome measurements had evidence of reliability and validity. However, the sample sizes were small, the selection and allocation of participants were inadequate, and the follow-up assessments were scarce. It is also noted that randomized controlled designs were inadequate in the pooled dataset, which can overcome some of these shortages and is strongly recommended in interventional studies.

Publication bias can also affect the results of a meta-analysis. Several methods were therefore used to evaluate publication bias in this study. Our data indicated a possibility of publication bias in the pooled dataset. It is possible that potential factors were confounding the results, such as the selection bias, the sample size of each study as well as the total number of studies. In addition, the exclusion of publications from other languages might have an impact on publication bias.

Limitations and Future Research

There were some limitations in this study. The standard deviation was not directly available in one study (Lang et al., 2020). We, therefore, imputed the standard deviation from another study which used the same outcome measure according to the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Wells, 2011). The current review was limited by the overall small sample sizes as well as the number of controlled studies. We demonstrated a protective effect in controlled trials only in the presence of a therapist. Due to the limited number of studies, we could not explore the benefits of self-compassion-focused interventions on different types of trauma which may benefit from the interventions in a different manner (Amstadter & Vernon, 2008; Breslau et al., 1998; Maheux & Price, 2015).

The results of the current study provided insights for future investigations. Only three RCT studies were identified in this review (Lang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2017; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019), which calls for more controlled trials of high quality using self-compassion-focused interventions. Online training with a therapist may be an effective and economical option for PTSD, especially during the COVID-19 epidemic. Long-term effects on PTSD have to be validated as only a few studies assessed follow-up effects in self-compassion-focused interventions (Au et al., 2017; Kearney et al., 2013; Valenstein-Mah et al., 2019). In addition, it is still unclear the psychological, physiological, or neurological processes underpinning the protective effects of self-compassion-focused interventions on PTSD.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and methodology. XL and XC conducted the analysis, literature search, and manuscript preparation. YL and HL reviewed and edited drafts and supervised the processes. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Funding

HL is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671150), Shenzhen-Hong Kong Institute of Brain Science-Shenzhen Fundamental Research Institutions (2019SHIBS0003) and Shenzhen Basic Research Scheme (JCYJ20150729104249783). XC is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (4045F41120040) and the Provincial Advantage Discipline Project (20JYXK034).

Availability of data and material

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from Supplementary Material S3.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allen AB, Leary MR. Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2010;4(2):107–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Vernon LL. Emotional reactions during and after trauma: A comparison of trauma types. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2008;16(4):391–408. doi: 10.1080/10926770801926492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Au TM, Sauer-Zavala S, King MW, Petrocchi N, Barlow DH, Litz BT. Compassion-based therapy for trauma-related shame and posttraumatic stress: Initial evaluation using a multiple baseline design. Behavior Therapy. 2017;48(2):207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow MR, Turow REG, Gerhart J. Trauma appraisals, emotion regulation difficulties, and self-compassion predict posttraumatic stress symptoms following childhood abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;65:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax, L. (2011). MIX 2.0. Professional software for meta-analysis in excel. Available at: https://www.meta-analysis-made-easy.com/

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bistricky SL, Gallagher MW, Roberts CM, Ferris L, Gonzalez AJ, Wetterneck CT. Frequency of interpersonal trauma types, avoidant attachment, self-compassion, and interpersonal competence: A model of persisting posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2017;26(6):608–625. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1322657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cȃndea D-M, Szentágotai-Tătar A. The impact of self-compassion on shame-proneness in social anxiety. Mindfulness. 2018;9(6):1816–1824. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-0924-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Che X, Cash R, Chung S, Fitzgerald PB, Fitzgibbon BM. Investigating the influence of social support on experimental pain and related physiological arousal: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018;92:437–452. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Earlbam Associates.

- Diedrich A, Burger J, Kirchner M, Berking M. Adaptive emotion regulation mediates the relationship between self-compassion and depression in individuals with unipolar depression. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2017;90(3):247–263. doi: 10.1111/papt.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj-British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AP, Mascaro JS, Kohn JN, Dobrusin A, Darcher A, Starr SD, Craighead LW, Negi LT. Compassion meditation training for emotional numbing symptoms among veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2019;25(4):441–443. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M, Hunt C, Harrysunker A, Abbott MJ, Beath AP, Einstein DA. Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness. 2019;10(8):1455–1473. doi: 10.1007/s12671-019-01134-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galili-Weinstock L, Chen R, Atzil-Slonim D, Bar-Kalifa E, Peri T, Rafaeli E. The association between self-compassion and treatment outcomes: Session-level and treatment-level effects. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018;74(6):849–866. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-García M, Álvarez JC, Pérez EZ, Fernandez-Carriba S, López JG. Feasibility of a brief online mindfulness and compassion-based intervention to promote mental health among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mindfulness. 2021;12(7):1685–1695. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01632-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodin J, Clark JL, Kolts R, Lovejoy TI. Compassion focused therapy for anger: A pilot study of a group intervention for veterans with PTSD. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2019;13:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan M, Vandekerckhove J. A Bayesian approach to mitigation of publication bias. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2016;23(1):74–86. doi: 10.3758/s13423-015-0868-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick LA, Owens GP. Exploring the mediating role of self-blame and coping in the relationships between self-compassion and distress in females following the sexual assault. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2019;75(4):766–779. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, L., & Olkin, I. (2014). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic.

- Held P, Owens GP. Effects of self-compassion workbook training on trauma-related guilt in a sample of homeless veterans: A pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2015;71(6):513–526. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held, P., Owens, G. P., Thomas, E. A., White, B. A., & Anderson, S. E. (2018). A pilot study of brief selfcompassion training with individuals in substance use disorder treatment. Traumatology, 24(3), 219. 10.1037/trm0000146

- Higgins, J., & Wells, G. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj-British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart A, Øktedalen T, Langkaas TF. Self-compassion influences PTSD symptoms in the process of change in trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies: A study of within-person processes. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:1273. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huwaldt, J. A. (2010). Open Source Software. Available at. http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net/

- Hwang W-C, Chan CP. Compassionate meditation to heal from race-related stress: A pilot study with Asian Americans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(4):482. doi: 10.1037/ort0000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inwood E, Ferrari M. Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2018;10(2):215–235. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney DJ, Malte CA, McManus C, Martinez ME, Felleman B, Simpson TL. Loving-kindness meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(4):426–434. doi: 10.1002/jts.21832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JN, Gilbert P. Commentary regarding Wilson et al.(2018)“Effectiveness of ‘self-compassion’ related therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” All is not as it seems. Mindfulness. 2019;10(6):1006–1016. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-1088-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kok BE, Coffey KA, Cohn MA, Catalino LI, Vacharkulksemsuk T, Algoe SB, Brantley M, Fredrickson BL. How positive emotions build physical health: Perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between positive emotions and vagal tone. Psychological Science. 2013;24(7):1123–1132. doi: 10.1177/0956797612470827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Malaktaris AL, Casmar P, Baca SA, Golshan S, Harrison T, Negi L. Compassion meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: A randomized proof of concept study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32(2):299–309. doi: 10.1002/jts.22397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Casmar P, Hurst S, Harrison T, Golshan S, Good R, Essex M, Negi L. Compassion meditation for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A nonrandomized study. Mindfulness. 2020;11(1):63–74. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0866-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence VA, Lee D. An exploration of people's experiences of compassion-focused therapy for trauma, using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2014;21(6):495–507. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. A., & James, S. (2013). The compassionate-mind guide to recovering from trauma and PTSD: Using compassion-focused therapy to overcome flashbacks, shame, guilt, and fear. New Harbinger Publications.

- Lee MY, Zaharlick A, Akers D. Impact of meditation on mental health outcomes of female trauma survivors of interpersonal violence with co-occurring disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017;32(14):2139–2165. doi: 10.1177/0886260515591277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenferink LI, Eisma MC, de Keijser J, Boelen PA. Grief rumination mediates the association between self-compassion and psychopathology in relatives of missing persons. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2017;8(sup6):1378052. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1378052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hu Y, Yang W, Wang Y. Daily interventions and assessments: The effect of online self-compassion meditation on psychological health. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2021;00:1–16. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz B, Carney JR. Employing loving-kindness meditation to promote self-and other-compassion among war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Spirituality in Clinical Practice. 2018;5(3):201. doi: 10.1037/scp0000174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G., Zhang, N., Teoh, J. Y., Egan, C., Zeffiro, T. A., Davidson, R. J., & Quevedo, K. (2020). Self-compassion and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activity during sad self-face recognition in depressed adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 1–10.10.1017/S0033291720002482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luo X, Qiao L, Che X. Self-compassion modulates heart rate variability and negative affect to experimentally induced stress. Mindfulness. 2018;9(5):1522–1528. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-0900-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Liu J, Che X. Investigating the influence and a potential mechanism of self-compassion on experimental pain: Evidence from a compassionate self-talk protocol and heart rate variability. The Journal of Pain. 2020;21(7–8):790–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz J, Berry MP, Napadow V, Germer C, Pollak S, Gardiner P, Edwards RR, Desbordes G, Schuman-Olivier Z. Neural activations during self-related processing in patients with chronic pain and effects of a brief self-compassion training–a pilot study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2020;304:111155. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2020.111155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(6):545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheux A, Price M. Investigation of the relation between PTSD symptoms and self-compassion: Comparison across DSM IV and DSM 5 PTSD symptom clusters. Self and Identity. 2015;14(6):627–637. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2015.1037791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maheux A, Price M. The indirect effect of social support on post-trauma psychopathology via self-compassion. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;88:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AE, Whittingham K, Steindl S, Kirby J. Feasibility and acceptability of a brief online self-compassion intervention for mothers of infants. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2018;21(5):553–561. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0829-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Meddicne. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2(3):223–250. doi: 10.1080/15298860309027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69(1):28–44. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, W. J., & Hine, D. W. (2019). Self-compassion, physical health, and health behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 127.10.1080/17437199.2019.1705872 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rockliff H, Gilbert P, McEwan K, Lightman S, Glover D. A pilot exploration of heart rate variability and salivary cortisol responses to compassion-focused imagery. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation. 2008;5(3):132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Scoglio AA, Rudat DA, Garvert D, Jarmolowski M, Jackson C, Herman JL. Self-compassion and responses to trauma: The role of emotion regulation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018;33(13):2016–2036. doi: 10.1177/0886260515622296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpa JG, Bourey CP, Adjaoute GN, Pieczynski JM. Mindful self-compassion (MSC) with veterans: A program evaluation. Mindfulness. 2021;12(1):153–161. doi: 10.1007/s12671-020-01508-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sirois FM, Molnar DS, Hirsch JK. Self-compassion, stress, and coping in the context of chronic illness. Self and Identity. 2015;14(3):334–347. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2014.996249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2004;1(3):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SG. Systematic review: Why sources of heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be investigated. Bmj-British Medical Journal. 1994;309(6965):1351–1355. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6965.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BL, Waltz J. Self-compassion and PTSD symptom severity. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2008;21(6):556–558. doi: 10.1002/jts.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk, F., & Waller, G. (2020). Is self-compassion relevant to the pathology and treatment of eating and body image concerns? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 101856.10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101856 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Valdez CE, Lilly MM. Self-compassion and trauma processing outcomes among victims of violence. Mindfulness. 2016;7(2):329–339. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0442-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein-Mah H, Simpson TL, Bowen S, Enkema MC, Bird ER, Cho HI, Larimer ME. Feasibility pilot of a brief mindfulness intervention for college students with posttraumatic stress symptoms and problem drinking. Mindfulness. 2019;10(7):1255–1268. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-1077-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin, K. E., Perman, G., & Simonds, L. M. (2021). Effectiveness of self‐compassion related interventions for reducing self‐criticism: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 1–25. 10.1002/cpp.2586 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winders SJ, Murphy O, Looney K, O'Reilly G. Self-compassion, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2020;27(3):300–329. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller, M., Yuval, K., Nitzan-Assayag, Y., & Bernstein, A. (2015). Self-compassion in recovery following potentially traumatic stress: Longitudinal study of at-risk youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology,43(4), 645–653. 10.1007/s10802-014-9937-y [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from Supplementary Material S3.