Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the influence of viscosupplementation on osteoarthritic knee arthrokinematics analyzed by VAG. It is considered that intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection may improve the function of synovial joints by recovery of friction-reducing properties of articular environment.

Design

Thirty-five patients with knee osteoarthritis (grade II according to the Kellgren-Lawrence system) and 50 asymptomatic subjects were enrolled in the study. Patients were analyzed at 3 time points: 1 day before and 2 weeks and 4 weeks after single injection of 1.5% cross-linked hyaluronate. Control subjects were tested once. The vibroarthrographic signals were collected during knee flexion/extension motion using an accelerator and described by variation of mean square (VMS), mean range (R5), and power spectral density for frequency of 50 to 250 Hz (P1), and 250 to 450 Hz (P2).

Results

Patients before viscosupplementation were characterized by about 2-fold higher values of vibroarthrographic parameters than controls. Two weeks after the procedure, the values of R5, P1, and P2 significantly decreased, in comparison to pre-injection. At 4 weeks post-injection, we noted a significant increase in R5, P1, and P2 values, when compared to 2 weeks post-injection. Finally, at 4 weeks post-injection, the level of VMS, R5, and P2 parameters did not differ from values obtained at pre-injection.

Conclusions

We showed that viscosupplementation may be effective in providing arthrokinematics improvement, but with a relatively short period of duration. This phenomenon is observed as decreased vibroacoustic emission, which reflects a more smooth movement in the joint.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, crepitus, hyaluronic acid, cartilage, friction

Introduction

Viscosupplementation (VS) is an intra-articular therapeutic modality based on the physiological importance of hyaluronic acid (HA) in the synovial joints (diarthrosis).1 VS is often used for local treatment of knee osteoarthritis (OA), and its usefulness is receiving support from a rapidly increasing number of recommendations and meta-analyses.2-7 Although possible mechanisms of VS action have not been fully elucidated and remain controversial, reported benefits of HA injections include moderate anti-inflammatory action, reduced cytokine-induced enzyme production, antioxidant action, anabolizing effect on cartilage, and direct analgesia by masking joint nociceptors.2,8-10 However, injecting exogenous HA into the joint is not only intended to achieve certain biological effects but also to restore the biomechanical properties of the articular environment. HA is considered to be crucial to the viscoelastic features of hyaline cartilage and synovial fluid, which in physiological conditions provides nearly frictionless arthrokinematic motion.11-14

The development of degenerative joint disease is associated with biomechanical and/or morphological alterations within the entire articular environment, resulting in, among others, cartilage degeneration and decreased rheological properties of synovial fluid.8,15 These changes, associated with impaired concentrations of hyaluronan, cause increased kinetic friction, which in mild-to-severe knee OA is often manifested as crepitus during joint motion.16-18 Clinicians often consider these deteriorations signs of impaired quality of arthrokinematic motion with crepitus being a criteria for diagnosis of gonarthrosis among the American College of Rheumatology.19,20 Previously, the level of vibroacoustic emission, based on vibroarthrography (VAG), has been shown to correspond highly with the degree of chondral deteriorations.13,14,21 It was reported that OA knees produce acoustic emissions with a greater frequency, higher peaks, and longer duration compared to healthy knees.18 Nevertheless, in vitro studies and analysis performed on animal models showed that intra-articular injection of HA improved joint lubrication and decreased kinetic friction coefficients.1,22-24 Therefore, based on these results, it can be hypothesized that VS may improve the function of synovial joints affected by OA, especially by facilitating joint movement, considered as a recovery of friction-reducing properties of arthrokinematics. Nonetheless, the direct impact of HA intra-articular injections on the quality of human knee motion has not been previously studied in vivo in clinical conditions.

The primary aim of our study was to evaluate the influence of VS on knee arthrokinematics in patients with OA, using the VAG method. Second, we applied the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) for assessing the overall health status of our patients in an effort to evaluate the effects of this treatment on patient-reported functional status. We believe that such complementary analysis provides a new perspective on the effects of VS and could broaden clinicians’ knowledge related to joint biotribology and especially the behavior of diarthroses with additional lubrication in order to restore normal arthrokinematics. This seems to be an essential clinical issue, due to the steadily increasing frequency of intra-articular injections of HA.

Methods

Subjects

Seventy-nine subjects were eligible for this study and were selected from a list of patients that qualified for an intra-articular injection of HA. Individuals were included on the basis of medical interview, physical examination, and imaging via standard radiographs done within 6 months of our enrollment date. Following the main inclusion criteria, all patients were between the ages of 45 and 65 years. All subjects were diagnosed with mild knee OA (grade II according to the Kellgren-Lawrence grading system) with a disease duration of more than 2 years. All diagnoses were conducted by a medical doctor according to the American College of Rheumatology.25

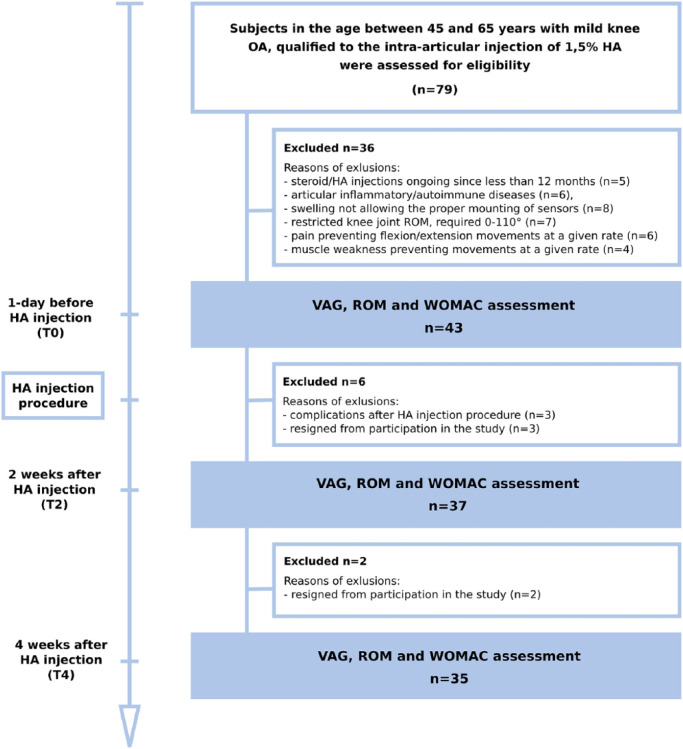

Exclusion criteria included symptomatic OA of the contralateral knee or either hip unresponsive to paracetamol, presence of articular inflammatory or autoimmune diseases, and corticosteroid/VS injections less than 12 months from the time of the study. To prevent any signal artifacts from deteriorations other than chondral lesions, individuals with a history of knee fracture, knee surgery, significant knee instability, or patellar maltracking were not enrolled in the study. Moreover, due to the methodology of the VAG assessment, individuals with restricted knee joint range of motion (required 0° to 100°), significantly weakened muscles, and substantially swollen knees in the affected lower limb were excluded from the study. The final number of VS patients analyzed was 35 (19 woman and 16 men). These patients had a mean age of 51 years, and they were tested 3 times: 1 day before injection; 2 weeks after intra-articular injection; and 4 weeks after intra-articular injection. In each patient only one knee that satisfied the inclusion/exclusion criteria was analyzed. The flow of the participant selection and reasons for exclusion from the study and the scheme of assessment in particular time points are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the study design and flow of patients receiving viscosupplementation.

The control group consisted of 50 asymptomatic subjects. There were no statistically significant differences in anthropometric indices in comparison to the group of VS patients. For the control subjects their test leg (right or left) was randomly selected. By self-report and physical examination, control subjects had no history of serious injuries nor other knee pathology; however, this was not confirmed with radiological testing.

For detailed characteristics of all subjects, see Table 1. Signed informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to testing, and the rights of subjects were protected throughout testing. This project was approved by the Opole Ethics Committee, Poland.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics (Mean ± Standard Deviation).

| VS Group (n = 35) | Control Group (n = 50) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.4 ± 6.4 | 54.3 ± 6.1 |

| Sex (women/men) | 19/16 | 28/22 |

| Height (cm) | 169.3 ± 8.3 | 168.3 ± 8.0 |

| Weight (kg) | 75.2 ± 14.3 | 73.4 ± 11.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.2 ± 4.1 | 25.9 ± 3.3 |

| Subjects with bilateral OA | 22 (63%) | — |

| Subjects with unilateral OA (left/right) | 5 (14%)/8 (23%) | — |

| Duration of OA (years) | 7.1 ± 6.8 | — |

VS = viscosupplementation; BMI = body mass index; OA = osteoarthritis.

Hyaluronic Acid Injection

To avoid differences in response rates due to differences of efficacy related to HA formulations, all patients evaluated in this study underwent single intra-articular injection of 1.5% cross-linked hyaluronate, with intermediate molecular weight of 2.4 MDa. Preparations were provided in prefilled glass sterile disposable syringes containing 30 mg of HA in 2 mL of buffered physiological saline solution.

The knee intra-articular injections were performed as an outpatient procedure in the orthopedic clinic treatment room, by 3 trained senior orthopedists. Injections were administered through an anterolateral or anteromedial access with the knee flexed at 90° following appropriate asepsis and antisepsis procedures, using sterile instruments. Subjects received injections in only one knee during the treatment schedule.

Assessment of Quality of Arthrokinematic Motion

Performed analyses were based on standardized methodology described previously.14,20,29,30 Each knee was assessed for quality of arthrokinematic motion during an open chain flexion/extension task using an acceleration sensor placed 1 cm above the apex of the patella. In a seated position, the following procedures were performed: starting with loose hanging legs and the knees flexed at 90°, the test knee was then fully extended from 90° to 0°, and then returned to flexion (from 0° to 90°). These procedures were repeated a total of 5 times in a 10-second period. The constant velocities for this extension-flexion motion was maintained with a metronome set at 60 beats per minute. The angle of the knee joint was measured using an electro-goniometer, but because the VAG signal could be distorted by the electro-goniometer placement, which could generate noise signal, this procedure was only used during determination of the experimental condition before testing.

The VAG signals generated were collected using an acceleration sensor, model 4507B-00, with a multi-channel Nexus conditioning amplifier (Brüel & Kjær Sound & Vibration Measurement A/S, Denmark). The signals were recorded as a time series expressed in volts, with a frequency range of 0.7 to 1000 Hz and a sampling rate of 10 kHz. Each trial was high-pass filtered according to a 50 Hz threshold, to minimize noise artifacts (e.g., muscle tremor). The obtained signals ranged from 50 to 1000 Hz and were described using 4 parameters. The variability of the VAG signal was assessed by computing the mean-squared values of the obtained signal in fixed-duration segments of 5 ms each, and then computing the variance of the values of the parameter over the entire duration of the signal (VMS parameter). Moreover, for signal amplitude analysis the R5 parameter was used. Because 5 full flexion/extension motion cycles were completed, the R5 parameter was calculated as the difference between the mean of 5 maximal values and the mean of 5 minimal values.13,20,29

The frequency characteristics of the VAG signal were examined by short-time Fourier transform analysis. The short-time spectra were obtained by computing the discrete Fourier transform of segments with 150 samples each, the Hanning window, and the 100 samples overlap of each segment. The spectral activity was analyzed by summing the spectral power of the VAG signal in 2 bands: 50 to 250 Hz (P1 parameter) and 250 to 450 Hz (P2 parameter).13,20,29

Assessment of Patient Self-Reported Functional Status and Knee Joint Range of Motion

To evaluate the treatment effects on patient condition we used the WOMAC questionnaire. The WOMAC is a 24-item, self-reported measure consisting of 3 subscales: pain (5 items), stiffness (2 items), and physical function (17 items). We applied the Likert scaled version of the measure, which provides the following response options: 0 = none; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe; and 4 = extreme. Lower scores represent less pain, less stiffness, and greater levels of functional status. The total score ranges between 0 and 96, and the subscale scores can vary as follows: pain (0-20), stiffness (0-8), and physical function (0-68). Subjects responded to each item based on activities of daily living during the previous 48 hours. Subjects were also instructed to avoid the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or other painkillers 3 days prior testing.

Statistical Analysis

Before relevant statistical comparison of all obtained data, the distribution of values was checked with the method introduced by Shapiro-Wilk.26 Demographic and anthropometric characteristics of analyzed groups were presented as descriptive statistics, by means and standard deviations, and significant differences in means were tested by unpaired t test. Intragroup changes of VAG parameter values and WOMAC scores obtained from VS patients were analyzed with the Friedman repeated-measures ANOVA (when values demonstrated skewness) or one-way ANOVA for repeated measures (for data with Gaussian distribution). These changes were assessed at 1 day pre-injection, 2 weeks post-injection, and 4 weeks post-injection. When significant interactions were identified, the Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction or Tukey honest significant difference test were applied as post hoc analyses, respectively. For intergroup comparisons (VS vs. control), the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. For the correlation between VAG parameters and WOMAC scores, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient test was performed. P values <0.05 were considered as significant. Statistics were analyzed using PQStat (PQStat Software, Poland).

Results

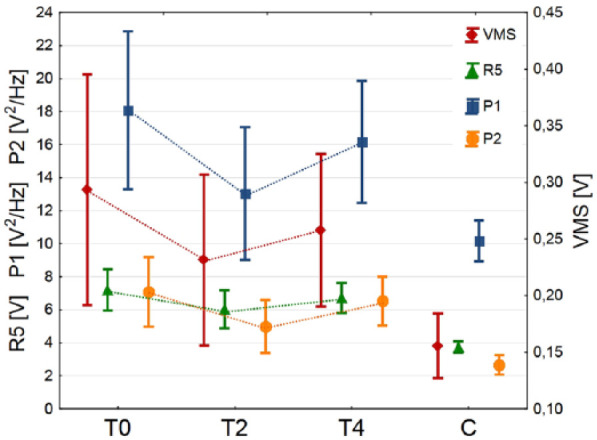

For analysis of the quality of arthrokinematic motion in VS and control groups, the median and variance values of VAG parameters were calculated for signals registered from 35 knees with moderate knee OA (tested 1 day before and 2 weeks and 4 weeks after HA injection), and from 50 control knees, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Moreover, for an additional expression of the VAG signals characteristics, representative plots of the signals course, specific for each analyzed condition and their respective spectrograms, have been presented in Figures 3 and 4.

Table 2.

Parameters of Vibroarthrographic Signals in Viscosupplementation Group and Control Group (Median ± Variance).

| VMS (V) | R5 (V) | P1 (V2/Hz) | P2 (V2/Hz) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (VS) | ||||

| 1 day before HA injection (T0) | 0.294 ± 0.296 | 7.21 ± 3.57 | 18.07 ± 13.93 | 7.08 ± 6.12 |

| 2 weeks after HA injection (T2) | 0.232 ± 0.220 | 6.02 ± 3.32 | 13.05 ± 11.70 | 4.98 ± 4.68 |

| 4 weeks after HA injection (T4) | 0.258 ± 0.196 | 6.72 ± 2.67 | 16.16 ± 10.74 | 6.53 ± 4.32 |

| Controls | 0.156 ± 0.101 | 3.75 ± 1.17 | 10.18 ± 4.36 | 2.67 ± 2.12 |

| P values for post hoc analysesa | ||||

| VS T0 vs. VS T2 | — | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VS T2 vs. VS T4 | — | 0.042 | 0.036 | <0.001 |

| VS T0 vs. VS T4 | — | 0.094 | 0.012 | 1.000 |

| VS T0 vs. Control | 0.102 | <0.001 | 0.025 | <0.001 |

| VS T2 vs. Control | 0.302 | <0.001 | 0.766 | <0.001 |

| VS T4 vs. Control | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

VMS = variability of the mean squares calculated in 5 ms windows; R5 = mean of 5 maximal and 5 minimal values; P1 and P2 = power spectral density bands: 50-250 Hz and 250-450 Hz, respectively; T0 = day pre-injection; T2 = 2 weeks post-injection; T4 = 4 weeks post-injection.

Bolded values indicate statistically significant differences.

Figure 2.

Values of vibroarthrographic parameters in the groups analyzed.

Figure 3.

Representative course of vibroarthrographic signals, with phases of movement from healthy individuals (A), patients before HA injection (B), patients 2 and 4 after weeks after HA injection (C and D, respectively).

Figure 4.

Signal time-frequency analysis representative for healthy individuals (A), patients before HA injection (B), patients 2 and 4 after weeks after HA injection (C and D, respectively).

Performed statistical analysis showed that VS patients before HA injection were characterized by about 2-fold higher values of VAG parameters than controls, with statistically significant difference for R5 (P < 0.001), P1 (P < 0.05), and P2 (P < 0.001). Figure 3 shows where the knees with OA generated signals course with higher amplitude, as compared to healthy ones. Analogous, time-frequency analysis exhibited differences in spectral activity between groups, especially in frequencies above 250 Hz (Fig. 4).

Studying the impact of HA injection on arthrokinematic changes within the VS group, a Friedman ANOVA test revealed statistically significant differences between the analyzed time points: χ2 = 18.51, P < 0.001; χ2 = 28.97, P < 0.001; χ2 = 24.74, P < 0.001, for R5, P1, and P2, respectively. Only the variability of mean squares parameter showed no main effect (χ2 = 5.99, P < 0.07). Subsequently, using post hoc tests we identified that 2 weeks after VS procedure, the values of R5, P1, and P2 parameters significantly decreased, in comparison to 1 day pre-injection (Table 2). It can be seen in Figures 3 and 4, where the characteristics of the VAG signal becomes more like those typical for the control group. This observation is also reflected in the absence of statistically significant differences between VS and control groups for variability (VMS) and spectral power in the range of 50 to 250 Hz (P1). Nevertheless, at 4 weeks post-injection, we noted a statistically significant increase in R5, P1, and P2 values, when compared to 2 weeks post-injection. Finally, at 4 weeks post-injection the level of VMS, R5, and P2 parameters did not differ from values obtained at pre-injection. Values of all VAG parameters were significantly higher in the VS group than in the control group.

The WOMAC scores in the group of patients receiving VS are shown in Table 3 and Figure 5. There was a statistically significant difference between several time points as determined by Friedman ANOVA for pain (χ2 = 22.05, P < 0.001), stiffness (χ2 = 20.53, P < 0.001), and function (χ2 = 24.44, P < 0.001) subscores, and by one-way ANOVA for repeated measures for total WOMAC scores (F = 27.45, P < 0.001). Post hoc analyses showed that at 2 weeks post-injection, there were no statistically significant differences for the WOMAC subscores and total scores, in comparison to the baseline condition. However, at 4 weeks post-injection the patients declared significant improvements in pain, stiffness, function, and total WOMAC scores, when compared to pre-injection (P < 0.001) and 2 weeks post-injection (P < 0.05). In addition, interactions between VAG parameters describing the quality of arthrokinematic motion and patients’ self-reported functional status expressed in WOMAC scores, collected at the same time points, were analyzed. There was a positive correlation between the values of P1 parameter and pain, function and total WOMAC scores (R = 0.35, P = 0.04; R = 0.41, P = 0.02; R = 0.40, P = 0.02, respectively), as well as between P2 parameter and function and total WOMAC scores (R = 0.38, P = 0.03; R = 0.36, P = 0.04), however, only before injection.

Table 3.

WOMAC Scores for Patients Receiving Viscosupplementation (Median ± Variance).

| Pain (0-20) | Stiffness (0-8) | Function (0-68) | Total (0-96) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMAC scores | ||||

| 1 day before HA injection | 5.6 ± 2.5 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 22.7 ± 7.3 | 30.1 ± 10.5 |

| 2 weeks after HA injection | 5.2 ± 2.8 | 2.6 ± 1.9 | 22.1 ± 7.3 | 29.9 ± 10.4 |

| 4 weeks after HA injection | 4.5 ± 2.7 | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 20.5 ± 7.1 | 26.6 ± 9.8 |

| P values for post hoc analysesa | ||||

| T0 vs. T2 | 0.320 | 1.000 | 0.454 | 0.111 |

| T2 vs. T4 | 0.022 | 0.007 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| T0 vs. T4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; HA = hyaluronic acid; T0 = 1 day pre-injection; T2 = 2 weeks post-injection; T4 = 4 weeks post-injection.

Bolded values indicate statistically significant differences.

Figure 5.

WOMAC scores for patients receiving viscosupplementation.

Discussion

Diarthroses possess complicated mechanics and are remarkable constructs, which provide the perfect compromise between mobility and stability. Moreover, physiologically they not only contribute to joint-specific ROM and distribute forces generated during joint loading, but in particular, the smooth and lubricated articular surfaces exhibit extremely low levels of friction.27,28 This phenomenon is clearly visible in analyses of joint motion quality based on the VAG method.20,29 It has been previously shown that healthy knee joints ensure optimal (low-friction, smooth, and practically vibration less) arthrokinematic motion, mainly determined by proper status of articular cartilage and optimal quantity as well as quality of synovial fluid.14 However, these properties decline with senescence, and increased VAG signal magnitude exhibits a strong correlation with the age-related changes within the biomechanical environment of synovial joints.16,30

Our results support the above-mentioned mechanism as we showed that the knee joints of our control group (mean age of 54 years) were characterized by VAG signals courses possessing slight, focal increases of amplitude and spectral power. This indicates minor arthrokinematic deteriorations, which are typical for this age group.30 On the other hand, patients with diagnosed knee mild OA (with similar age and anthropometric characteristics) manifested 2 times higher values of all analyzed VAG parameters than controls. When the plots of the obtained disorder-related signals were analyzed, the significantly higher variability of the signal courses was observed (Fig. 3), with presence of large peaks possessing high spectral power (Fig. 4). It should be noted that these hallmarks are not accidental but are repeated in each cycle of the extension-flexion motion, and in exactly the same knee position (Fig. 3). Generally, this observation reflects a high level of vibroacoustic emission of osteoarthritic knee joints, which in clinical conditions occurs as crackling and grinding sensations during movement, indicating an increased kinetic friction and considerably impaired joint motion quality.20,29,31

This phenomenon has been well described, and may be deliberated as a result of degenerative changes within the biomechanical environment of an affected joint.18,32,33 In the present study, we analyzed knees with grade II OA, according to the Kellgren-Lawrence classification, which implies that the joints in the radiographic examination demonstrated presence of osteophytes and possible joint space narrowing.25 However, in mild knee OA, pathological changes specifically affect intra- and extra-articular soft tissues, which are not detectable on X-ray image. Histopathological evaluations demonstrated that the principal feature of analyzed grade II OA is cartilage surface discontinuity, with focal fibrillation and vertical fissures extending into the mid zone, which results in cartilage erosion.34 These changes cause roughness and irregularity of articular surfaces, which together with declining lubrication possibilities and hypertrophy of the joint capsule may lead to increased contact stress and friction. As a result, motion is impaired, which may be indicated by our experimental subjects who presented with a high level of vibroacoustic emission.10,20,35,36

Our study primarily revealed that 2 weeks after HA injection there is a decrease in vibroacoustic emission compared to the baseline assessment. The statistically significant lower values of R5, P1, and P2 parameters prove that registered VAG signals possess decreased amplitude and spectral power in entire measured frequency range, which correspond to the generating of reduced, less prominent vibrations/crepitations during motion. A similar observation was presented previously; however, analysis of crackling during osteoarthritic knee movements before and after VS was a secondary outcome measurement, without deeper interpretation.37 It appears that this phenomenon may be explained by VS-related improvement of the viscoelastic properties of synovial fluid and mechanical benefits through direct lubrication, which is conducive to forming fluid-film layer on cartilage surfaces.38,39 This mechanism also seems likely, due to the lack of improvement in WOMAC scores and subscores during the analyzed time points, considered as signs of biological effects of VS. Research has shown that these changes often occur after longer periods (6-8 weeks) after HA injection, while mechanical effect occurs almost immediately after HA injection; however, the precise duration of action of HA still remains unknown.3,10 Thus, we hypothesize that this observed effect stem from a primarily mechanical background and is a result of restored rheological properties of the synovial fluid.37,39 However, we must point out that our observed improvement in arthrokinematics is incomplete, and despite the use of VS, patients were characterized by higher vibroacoustic level than controls. Therefore, it can be assumed that increased synovia content and its enhanced viscoelastic qualities only partially mask chondral lesions in the superficial or middle zones of hyaline cartilage, which are typical for mild gonarthrosis.34,35

Four weeks after HA injection there was a significant increase in all the above-mentioned VAG parameters compared to 2 weeks post-injection. Previous research, obtained by human and animal studies, have shown that synthetic injectable HA only briefly remains inside the joint, as it is rapidly degraded and absorbed after injection.2 However, it should be considered that the total residence time of HA in the joint cavity is strictly related to the degree of modification and cross-linking process. Linear HA typically has a joint residence time of 1 week whereas cross-linked HA has a significantly prolonged joint residence time. Nonetheless, our results suggest that VS-related arthrokinematic improvement may be a temporary characteristic making it unlikely that HA’s long-term therapeutic properties relate to its physical ability to improve lubrication. However, it should be mentioned that the values of P1 parameter (spectral power in the range of 50-250 Hz) at 4 weeks post-injection were still significantly lower than before HA injection. The decreased spectral power during this frequency band indicates the declining occurrence of slight vibrations associated with subtle chondral lesions, so it can be regarded as mitigated.14 However, lubrication may continue despite the short HA joint residence time, or as a result of the onset of biological/morphological changes within articular cartilage, especially its enhanced integrity related to improved proteoglycan content.1

The latter supposition can be supported by our outcomes that showed improvement of self-reported functional status, which occurred only 4 weeks after VS procedure. A slight, although statistically significant, reduction has been noted in all analyzed WOMAC categories (pain, stiffness, and function) and is considered as biological effect of VS and partial reestablishment of joint homeostasis.40,41 Thus, our WOMAC-related results seem to be in accordance to those previous works that showed that the highest clinical efficacy of HA occurs between 5 and 13 weeks after the beginning of intra-articular treatment.3,4 Nonetheless, most of the presented studies using self-reported functional status questionnaires (including our study) were nonblinded or single-blinded and did not include a placebo effect, which is a limitation. Meanwhile, meta-analysis of double-blinded, sham-controlled trials have not shown clinical differences between HA treatments and placebos.7,42 Therefore, interpretation of our results should consider the subjective character of our self-reported functional status questionnaire.

Another limitation of our study was that we did not assess chondral status via magnetic resonance imaging. This prevented us determining relationships between the condition of articular cartilage and the effectiveness of the VS in improving joint motion quality. Moreover, our study had a relatively short follow-up period of 1 month, which makes the long-term impact of VS on arthrokinematics unknown. Nevertheless, there is evidence to suggest that the presented method is sensitive for tribological changes within the articular environment and may be a helpful tool to monitor the effectiveness of VS using in knee OA treatment.43

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The reported work was done in the Opole University of Technology.

Acknowledgments and Funding: We would express our special gratitude to medical staff of Opole Rehabilitation Center for assistance. The participation in this study of all our patients and control volunteers is gratefully acknowledged. The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: This project was approved by the Opole Ethics Committee, resolution no. 202.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to testing, and the rights of subjects were protected throughout testing.

ORCID iD: Bączkowicz Dawid  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3094-0824

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3094-0824

References

- 1.Elmorsy S, Funakoshi T, Sasazawa F, Todoh M, Tadano S, Iwasaki N.Chondroprotective effects of high-molecular-weight cross-linked hyaluronic acid in a rabbit knee osteoarthritis model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Legré-Boyer V. Viscosupplementation: techniques, indications, results. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suppan VK, Wei CY, Siong TC, Mei TM, Chern WB, Kumar VKN, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing efficacy of conventional and new single larger dose of intra-articular viscosupplementation in management of knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017;25:2309499017731627. doi: 10.1177/2309499017731627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wehling P, Evans C, Wehling J, Maixner W.Effectiveness of intra-articular therapies in osteoarthritis: a literature review. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2017;9:183-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhadra AK, Altman R, Dasa V, Myrick K, Rosen J, Vad V, et al. Appropriate use criteria for hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis in the United States. Cartilage. 2017;8:234-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos ALS, Albuquerque RSP, da Silva EB, Fayad SG, Acerbi LD, de Almeida FN, et al. Viscosupplementation in patients with severe osteoarthritis of the knee: six month follow-up of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Int Orthop. 2017;41:2273-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jevsevar D, Donnelly P, Brown GA, Cummins DS.Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of the evidence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:2047-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholls MA, Fierlinger A, Niazi F, Bhandari M.The disease-modifying effects of hyaluronan in the osteoarthritic disease state. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;10:1179544117723611. doi: 10.1177/1179544117723611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lùrati A, Laria A, Mazzocchi D, Re KA, Marrazza M, Scarpellini M.Effects of hyaluronic acid (HA) viscosupplementation on peripheral Th cells in knee and hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:88-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowden DJ, Byrne CA, Alkhayat A, Eustace SJ, Kavanagh EC.Injectable viscoelastic supplements: a review for radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209:883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jay GD, Waller KA.The biology of lubricin: near frictionless joint motion. Matrix Biol. 2014;39:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamer TM.Hyaluronan and synovial joint: function, distribution and healing. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2013;6:111-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bączkowicz D, Falkowski K, Majorczyk E.Assessment of relationships between joint motion quality and postural control in patients with chronic ankle joint instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47:570-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bączkowicz D, Majorczyk E.Joint motion quality in chondromalacia progression assessed by vibroacoustic signal analysis. PM R. 2016;8:1065-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusayama Y, Akamatsu Y, Kumagai K, Kobayashi H, Aratake M, Saito T.Changes in synovial fluid biomarkers and clinical efficacy of intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid for patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Exp Orthop. 2014;1:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temple-Wong MM, Ren S, Quach P, Hansen BC, Chen AC, Hasegawa A, et al. Hyaluronan concentration and size distribution in human knee synovial fluid: variations with age and cartilage degeneration. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenz A, Rothstock S, Bobrowitsch E, Beck A, Gruhler G, Ipach I, et al. Cartilage surface characterization by frictional dissipated energy during axially loaded knee flexion—an in vitro sheep model. J Biomech. 2013;46:1427-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song SJ, Park CH, Liang H, Kim SJ.Noise around the knee. Clin Orthop Surg. 2018;10:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salehi-Abari I. 2016ACR revised criteria for early diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Autoimmune Dis Ther Approaches. 2016;3:118-23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bączkowicz D, Kręcisz K, Borysiuk Z.Analysis of patellofemoral arthrokinematic motion quality in open and closed kinetic chains using vibroarthrography. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:48. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2429-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Befrui N, Elsner J, Flesser A, Huvanandana J, Jarrousse O, Le TN, et al. Vibroarthrography for early detection of knee osteoarthritis using normalized frequency features. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2018;56:1499-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence A, Xu X, Bible MD, Calve S, Neu CP, Panitch A.Synthesis and characterization of a lubricin mimic (mLub) to reduce friction and adhesion on the articular cartilage surface. Biomaterials. 2015;73:42-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiavinato A, Whiteside RA.Effective lubrication of articular cartilage by an amphiphilic hyaluronic acid derivative. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2012;27:515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mainil-Varlet P, Schiavinato A, Ganster MM.Efficacy evaluation of a new hyaluronan derivative HYADD® 4-G to maintain cartilage integrity in a rabbit model of osteoarthritis. Cartilage. 2013;4:28-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND.Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1886-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shapiro S, Wilk M.An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika. 1965;52:591-611. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarafder S, Lee CH.In situ regeneration of osteochondral and fibrocartilaginous tissues by homing of endogenous cells. In: Lee SJ, Yoo JJ, Atala A, editors. In situ tissue regeneration. Boston: Academic Press; 2016. p. 253-73. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleemann RU, Krocker D, Cedraro A, Tuischer J, Duda GN.Altered cartilage mechanics and histology in knee osteoarthritis: relation to clinical assessment (ICRS Grade). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:958-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kręcisz K, Bączkowicz D.Analysis and multiclass classification of pathological knee joints using vibroarthrographic signals. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2018;154:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bączkowicz D, Majorczyk E, Kręcisz K.Age-related impairment of quality of joint motion in vibroarthrographic signal analysis. BioMed Res Inter. 2015;2015:591707. doi: 10.1155/2015/591707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obara T, Mabuchi K, Iso T, Yamaguchi T.Increased friction of animal joints by experimental degeneration and recovery by addition of hyaluronic acid. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1997;12:246-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crema MD, Guermazi A, Sayre EC, Roemer FW, Wong H, Thorne A, et al. The association of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-detected structural pathology of the knee with crepitus in a population-based cohort with knee pain: the MoDEKO study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:1429-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schiphof D, van Middelkoop M, de Klerk BM, Oei EH, Hofman A, Koes BW, et al. Crepitus is a first indication of patellofemoral osteoarthritis (and not of tibiofemoral osteoarthritis). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:631-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pritzker KP, Gay S, Jimenez SA, Ostergaard K, Pelletier JP, Revell PA, et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:13-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stitik TP, Levy JA.Viscosupplementation (biosupplementation) for osteoarthritis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(11Suppl):S32-S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ammar TY, Pereira TA, Mistura SL, Kuhn A, Saggin JI, Júnior OVL. Viscosupplementation for treating knee osteoarthrosis: review of the literature. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;50:489-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giarratana LS, Marelli BM, Crapanzano C, De Martinis SE, Gala L, Ferraro M, et al. A randomized double-blind clinical trial on the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: the efficacy of polynucleotides compared to standard hyaluronian viscosupplementation. Knee. 2014;21:661-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Askari A, Gholami T, NaghiZadeh MM.Hyaluronic acid compared with corticosteroid injections for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized control trial. Springerplus. 2016;5:442-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhandari M, Bannuru RR, Babins EM, Martel-Pelletier J, Khan M, Raynauld JP, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a Canadian evidence-based perspective. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2017;9:231-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altman RD, Manjoo A, Fierlinger A, Niazi F, Nicholls M.The mechanism of action for hyaluronic acid treatment in the osteoarthritic knee: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:321. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0775-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maheu E, Rannou F, Reginster JY.Efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid in the management of osteoarthritis: evidence from real-life setting trials and surveys. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4Suppl):S28-S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Annaswamy TM, Gosai EV, Jevsevar DS, Singh JR.The role of intra-articular hyaluronic acid in symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee. PM R. 2015;7:995-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dołęgowski M, Szmajda M, Bączkowicz D.Use of incremental decomposition and spectrogram in vibroacoustic signal analysis in knee joint disease examination. Przeglad Elektrotechniczny. 2018:94:162-6. [Google Scholar]