Abstract

Osteomas are benign tumours of bone tissue restricted to the craniofacial skeleton. The aim of this article is to present and discuss the demographic and clinical aspects and the management of craniomaxillofacial osteomas. When the patient was submitted from primary care to our hospital, he was 68 years old, and he had ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint for the previos 4 years. A CT scan was performed, finding a giant mandibular osteoma. Conservative treatment and radiological follow-up were carried out with clinical stability. Osteomas more often are seen in the paranasal sinuses and in young adults, with no differences in gender. Most are asymptomatic, but they can cause local problems. For its diagnosis, CT is usually performed. Treatment options are conservative management and follow-up or surgery. Although rarely, they can recur. Mandibular peripheral osteoma is a rare entity. Depending on the symptoms, a conservative or surgical treatment can be chosen. A clinical and radiological follow-up is necessary to detect possible recurrences or enlargement.

Keywords: dentistry and oral medicine, ear, nose and throat, ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology

Background

The authors consider that this is a rare case of mandibular giant osteoma in which clinical and radiological follow-up was made for 13 years, without any progression.

We provide a review of the literature on this topic.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old man attended the Otolaryngology Service of Hospital Doctor Peset (Valencia, Spain) referred from primary care, due to a suspicious image found on a left temporomandibular joint X-ray. This was performed because of the 3–4 years left mandibular ankylosis, with progressive trismus and moderate pain when opening the mouth. The X-ray shows a hyperdense area at the level of the zygomatic region. The patient had not had any trauma or infection in this area. He denies other bone, skin or intestinal haemorrhagic lesions, related to the clinical features of Gardner’s syndrome.

Investigations

Exploration: Slight difficult mouth opening (interdental distance: 3 cm) and left mandibular deviation. Endoral asymmetry is seen on the left side (figure 1). In nasofibrolaryngoscopy, middle meatus and cavum were normal, no lesions in the pharynx or larynx. No lymphadenopathy or other tumours on cervical palpation.

Analytics: Normal parameters.

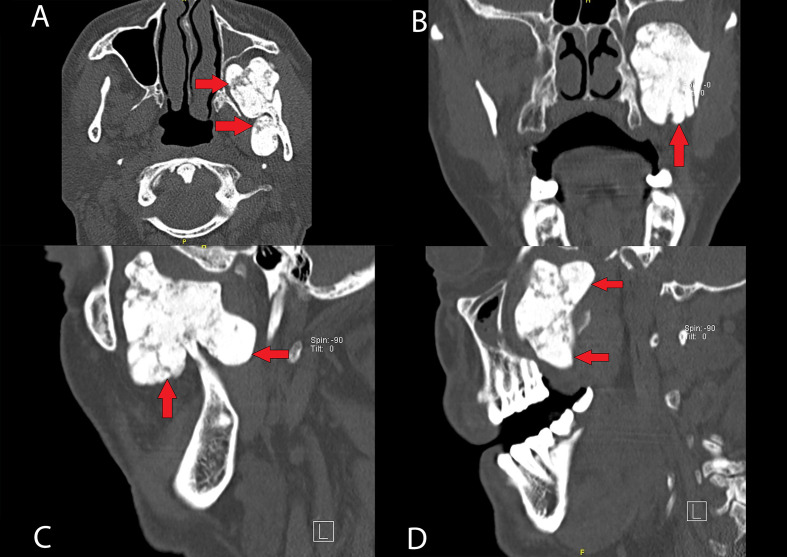

CT scan (figures 2A–D and 3A–C): Peripheral osteoma originating from the left ascending mandibular ramus, 45×33×50 mm (anteroposterior by transverse by craniocaudal), which occupies practically the entire left pterygopalatine fossa. It is a polylobulated tumour, well defined and homogeneously hyperdense, in continuity with the internal cortex of the left ascending ramus of the mandible, through a pedicle with a wide base. It presents an attenuation of the cortical bone, and deforms the posterior and lateral wall of the maxillary sinus, the left pterygoid process and the posteroinferior portion of the left maxilla, as well as the lateral wall of the left orbit. These findings correspond to chronicity. In both maxillary sinuses, mucosal thickening is identified in the most declining portion.

Figure 1.

Clinical pictures of the patient. Here we can see the slight difficult mouth opening (interdental distance: 3 cm) and left mandibular deviation. Endoral asymmetry is seen on the left side (A, B).

Figure 2.

Cranial CT scan imaging of the mandibular osteoma, different projections: axial (A), coronal (B) and sagittal (C, D). We can see a bony-like density mass, measuring 45×33×50 mm (pointed with arrows) and its anatomical relation with mandibular left condyle, in continuity with the internal cortex, as well as its polylobulated shape (A, C).

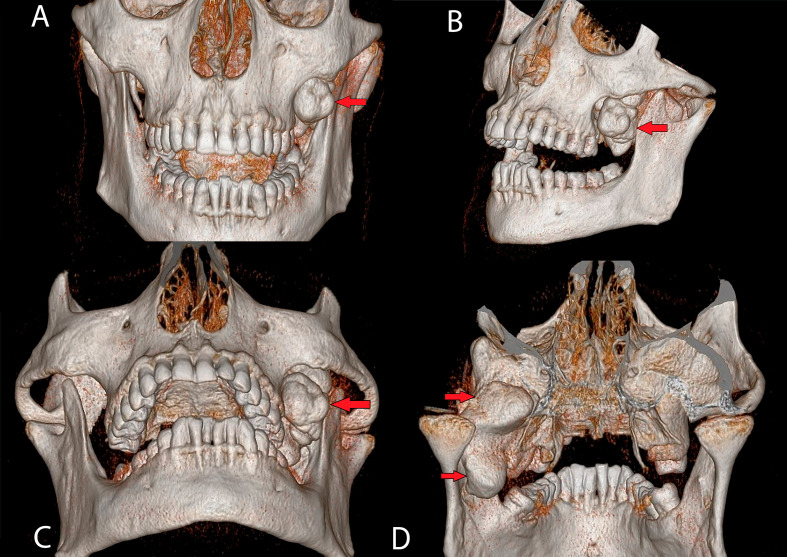

Figure 3.

3D CT scan reconstruction. Anterior (A), lateral (B), waters projection (C) and posterior (D) views. As we can see 3D gives us a better anatomic view, easier-to-understand anatomic relations, and it can be useful for surgical planning. 3D, three dimensions.

Differential diagnosis

Osteomas are characterised by slow and continuous growth, in most cases limited, although there are a few cases that reach large dimensions, the so-called gigantiform osteomas. This benign neoplasm can have a silent behaviour for years and grow without giving any symptom, and usually is diagnosed when it becomes large enough to cause local problems or when radiological tests are performed for other reasons.

Gold standard for diagnosis is the CT scan, which allows a correct description of the size and its relationship with neighbouring structures. It appears as a radiopaque, oval and well-defined mass, with a bone-like density. Most osteomas are single, lobulated and attached to the cortex by a sessile or broad pedunculated mushroom-shaped base.

A differential diagnosis should be made with osteoblastoma, osteoid osteoma (which appears as a well-defined radiolucent area), bone exostoses, (including torus) and with other inflammatory and neoplastic pathologies such as chronic focal sclerosing osteomyelitis, ossifying fibroma, chondroma, osteosarcoma or Paget’s disease.

Treatment

Osteomas can be managed either conservative or surgically. Treatment will be chosen depending on factors such as patient’s clinical features, age or comorbidities. Generally, the authors opt for observation and periodic radiological follow-up due to its slow growth. When there is aesthetic and/or functional repercussion, a surgical excision may be performed. The intraoral or combined approach provides better aesthetic outcomes, and avoids facial nerve’s injuries. On the other hand, extraoral approach provides greater visibility and access.

Use of three-dimensional (3D) imaging helps surgical planning, minimising the extraoral approach in mandibular giant osteomas. Endoscopic access emerges as a successful alternative in the maxillary and condylar approach, with a reduction in morbidity, scarring, facial nerve injury and recovery time. Furthermore, piezosurgery allows bone extraction without damaging the surrounding soft-tissues, reducing postoperative inflammation, pain and dysesthesia. When the mandibular condyle is affected, it must be reconstructed either by autogenous bone grafts or total prosthetic joints.

Even if they are surgically treated, osteomas can recur, although they rarely do. If there is not surgical treatment, they can keep on growing slowly. Hence the importance of their clinical and radiological follow-up. There is no evidence of osteomas malignant transformation.

Outcome and follow-up

In this case, a conservative treatment and annual follow-up with CT scan was decided. It was performed annually for the first 3 years and afterwards each 5 years.

After 13 years of clinical and radiological follow-up, the described lesion remains stable without any changes.

Discussion

Osteomas are well-differentiated benign tumours of bone tissue.1–6 They represent 2%–3% of all primary bone tumours,1 are essentially restricted to the craniofacial skeleton and rarely occur in other bones.3 Giant osteomas in the mandible are exceptional.3 7 8 Paranasal sinuses are the most affected area,1 2 4 5 9 10 even though they can be seen in more infrequent locations such as: external auditory canal, temporal bone, orbit, pterygoid processes, zygomatic arch and rarely in the mandible.1 3 10

Parts of the mandible where they most frequently originate are body (alveolar area on its lingual side), condyle, angle, ramus of the mandible, coronoid process and sigmoid notch.1 3–5 10 11

Whenever multiple osteomas are found, Gardner’s syndrome should be studied.1 5 10 12 This is an autosomal dominant inherited disease that associates multiple osteomas, colorectal adenomatous polyps (with high probability of malignancy) and cutaneous epidermoid cysts.1 3 10 12–14 Less than 10% present the triad and only 14% have a skeletal feature.3 However, about 80% of those show early signs in the maxillofacial area, and ignoring them can delay the diagnosis, compromising the management of the patient. Therefore, otolaryngologists play an important role. A family history of intestinal polyposis should be suspected, and the patient should be referred to an adequate gastrointestinal evaluation.14

Osteomas can be seen at any age, being more common in young adults.3 9 10 There is a wide range in the age of presentation as seen in the literature, varying between 14 and 58 years old,1 with an average age of 30 years according to Espinosa et al,1 and approximately 50 according to Boffano et al2

There is controversy regarding gender: in some studies, there is no difference.3 10 In others looks like men are more frequently affected,1 9 and in others prevalence is higher in females.2 5

Regarding its nature, no cause has been proven. Several aetiopathogenic theories have been proposed, including reactive bone hyperplasia from cartilaginous and periosteal embryological remnants, trauma and chronic inflammation.2 3 For other authors, they are true bone tumours.1–5 9–11

Histologically, osteomas can be divided into compact, spongy and mixed osteomas. The compact ones appear as a dense bone, while the spongy ones contain a greater medullary space.1–6 8–10

According to their growth, they have also been classified in three types:

Peripheral (periosteal): They are the most frequent ones.1 They have a centrifugal growth from the periosteum, showing as sessile masses linked to the cortical plates, as observed in the case presented in this work.

Central (endosteal): Centripetal endosteal growth, towards the medullary bone.

Extra skeletal: Arises from soft tissues, such as skeletal muscle.1 2 4–6 8–10

This benign neoplasm can be clinically asymptomatic for years, and usually is diagnosed either when it becomes large enough to cause local problems (pain, neurovascular compression, trismus, facial asymmetry, malocclusion, defects in oral function) or incidentally when radiological tests are performed for other reasons.1–3 5 6 8 9 12

Diagnostic gold standard is CT scan,3 8–10 which allows to delimit the size and its relationship with its neighbouring structures.1 5 It appears as a radiopaque, oval, and well-defined mass, with a bone-like density.1 3 6 8–12 Most osteomas are single, lobulated and attached to the cortex by a sessile or broad pedunculated mushroom-shaped base.3 10

As previously said, treatment will depend on various clinical factors. Either conservative or surgical treatment will be chosen.5 7–9 12 14 If there is not aesthetic and/or functional repercussion, observation and follow-up is preferred.1–3 5 6 9 14

Whenever surgical treatment is chosen, intraoral or combined approach are preferable for aesthetic reasons and to avoid facial nerve injuries, despite the extraoral approach provides greater visibility and access.1 5 7 3D surgical planning can help in minimising the extraoral approach in mandibular osteomas,7 and recent advances in endoscopic maxillary and condylar approach emerge as an alternative, decreasing morbidity, scarring, facial nerve injury and recovery time.9 Also, piezosurgery allows bone removal without damaging the surrounding soft tissues, reducing postoperative inflammation, pain and dysesthesia.5 As for mandibular condyle region reconstruction autogenous bone grafts or total prosthetic joints that replace the temporomandibular joint can be used.12 15

Although infrequent, surgically removed mandibular osteomas can recur. If left without removal it is not rare that they keep on growing slowly, even though there is no evidence of its malignant transformation.1–3 5–11

Mandibular single giant osteomas such as the one presented are a rare entity. In this case, aesthetic and functional symptoms were not a concern for the patient, and clinical and imaging follow-up were done, in agreement with patient’s preferences. Curiously the osteoma has not grown ever in the past 13 years, which makes the case a singular and successful outcome of conservative management in this entity.

Patient’s perspective.

The patient was given a full explanation with the benefits and risks of the different treatment options. Final decision was made in agreement with him being always an active participant in the decision making. Currently, he attends his annual follow-up appointments and he is very satisfied with the treatment received.

Patient’s point of view: ‘I came to this hospital 13 years ago seeking for an advice or treatment for my problems. I was excellently atended, communication was always fluent with doctor’s team. They told me it was a benign problem that might or might not grow, so finally we decided conservative treatment, without any changes until now. I’m really happy with this decision’.

Learning points.

Osteomas are benign bone neoplasms, with virtually no malignant transformation. Their main location is the craniofacial skeleton, specially the paranasal sinuses. Mandibular osteomas are a rare entity.

Whenever multiple osteomas are found a gastrointestinal evaluation to rule out Gardner’s syndrome must be done.

Most osteomas are asymptomatic, but they can give local problems because of their growing. Nowadays CT scan is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Depending on the symptoms and patient’s features and preferences, either a conservative or surgical treatment can be chosen.

Clinical and radiological follow-up are necessary to detect possible recurrences or enlargement.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the participants contribute in the work. NOB and FPR: patient care, diagnostic tests, diagnosis, follow-up and evolution. Writting the paper MMA and SMQ: bibliographic search.

Funding: This study was funded by Universitat de València.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Espinosa Fernández J, Rodríguez Luna R, Ortiz Cruz AB. Osteoma mandibular periférico. Rev Mex Cirugía Bucal y Maxilofac 2017;13:60–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boffano P, Roccia F, Campisi P, et al. Review of 43 osteomas of the craniomaxillofacial region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;70:1093–5. 10.1016/j.joms.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gawande P, Deshmukh V, Garde JB. A giant osteoma of the mandible. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2015;14:460–5. 10.1007/s12663-010-0112-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nah K-S. Osteomas of the craniofacial region. Imaging Sci Dent 2011;41:107. 10.5624/isd.2011.41.3.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dell'Aversana Orabona G, Salzano G, Iaconetta G, et al. Facial osteomas: fourteen cases and a review of literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2015;19:1796–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohashi Y, Kumagai A, Matsumoto N, et al. A huge osteoma of the mandible detected with head and neck computed tomography. Oral Sci Int 2015;12:31–6. 10.1016/S1348-8643(14)00029-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazar A, Brookes CCD. Giant osteomas: optimizing outcomes through virtual planning; a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;79:366–75. 10.1016/j.joms.2020.07.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadeghi HM, Shamloo N, Taghavi N, et al. Giant osteoma of mandible causing dyspnea: a rare case presentation and review of the literature. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2015;14:836–40. 10.1007/s12663-014-0717-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Conto F. Odontoestomatología. 15. Facultad de Odontología, Universidad de la República, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayan NB, Uçok C, Karasu HA, et al. Peripheral osteoma of the oral and maxillofacial region: a study of 35 new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;60:1299–301. 10.1053/joms.2002.35727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johann ACBR, de Freitas JB, de Aguiar MCF, Rodrigues Johann ACB, Ferreira de Aguiar MC, et al. Peripheral osteoma of the mandible: case report and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2005;33:276–81. 10.1016/j.jcms.2005.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Souza NT, Cavalcante RCL, de Albuquerque Cavalcante MA, et al. An unusual osteoma in the mandibular condyle and the successful replacement of the temporomandibular joint with a custom-made prosthesis: a case report. BMC Res Notes 2017;10:727. 10.1186/s13104-017-3060-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charifa A, Jamil RT, Zhang X. Gardner syndrome. StatPearls, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldino ME, Koth VS, Silva DN, et al. Gardner syndrome with maxillofacial manifestation: a case report. Spec Care Dentist 2019;39:65–71. 10.1111/scd.12339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostrofsky M, Morkel JA, Titinchi F. Osteoma of the mandibular condyle: a rare case report and review of the literature. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2019;120:584–7. 10.1016/j.jormas.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]