Abstract

During the early days of the pandemic and in the context of a seemingly unknown global threat, several potential major sleep disruptors were identified by sleep researchers and practitioners across the globe. The COVID-19 pandemic combined several features that, individually, had been shown to negatively affect sleep health in the general population. Those features included state of crisis, restrictions on in-person social interactions, as well as financial adversity. To address the lack of a comprehensive summary of sleep research across these three distinctive domains, we undertook three parallel systematic reviews based on the following themes: 1) Sleep in times of crises; 2) Sleep and social isolation; and 3) Sleep and economic uncertainty. Using a scoping review framework, we systematically identified and summarized findings from these three separated bodies of works. Potential moderating factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, psychological predisposition, occupation and other personal circumstances are also discussed. To conclude, we propose novel lines of research necessary to alleviate the short- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 crises and highlight the need to prepare the deployment of sleep solutions in future crises.

Keywords: Sleep, COVID-19, Crisis, Pandemic, Social isolation, Loneliness, Economic uncertainty, Recession, Systematic review

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease of 2019

- ISI

Insomnia severity scale

- OR

Odds ratio

- OSA

Obstructive sleep apnea

- PHQ

Patient health questionnaire

- PSQI

Pittsburgh sleep quality index

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Glossary of terms

- Loneliness

Discrepancy between an individual's desired and actual relationships. It is thus an unpleasant emotional interpretation of one's own social circumstances.

- Social isolation

Absence of social interactions, contacts, and relationships with family and friends, with neighbors on an individual level, and with “society at large” on a broader level.

- Financial adversity

Insufficient financial resources to adequately meet one's household's needs.

- Pandemic

An outbreak of a disease that occurs over a wide geographic area (such as multiple countries or continents) and typically affects a significant proportion of the population.

Introduction

In 2020, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic caused sickness and deaths, leading to important disruption in individuals’ lives and the global economy. Public health measures aimed at limiting the spread of COVID-19, and fear of infection affected everyday routines, by limiting social, educational and work activities. Consequently, the COVID-19 pandemic reshaped public spaces and their use, as well as the home environment, as social distancing measures, and school and business closures mandated where people studied, worked and spent leisure time. In the context of COVID-19, government-imposed stay-at-home orders and temporary closure of nonessential businesses and organizations left many without employment and forced others to work or attend classes from home, causing stress and interfering with daily routines and sleep-wake schedules.

During the early days of the pandemic and in the context of a seemingly unknown global threat, several potential major sleep disruptors were identified by sleep researchers and practitioners across the globe. The COVID-19 pandemic combined several features that, individually, had been shown to negatively affect sleep health in the general population. Those features included stress, restrictions on in-person social interactions, as well as financial adversity due to an abrupt economic slowdown. Accordingly, researchers and practitioners scrambled to identify evidence that could be used to inform public policy and drew on early COVID-19 studies (as well as from the scientific literature on social isolation and financial adversity). To address the lack of a comprehensive summary of sleep research across these three distinctive domains, we undertook a systematic, qualitative review of the literature, using the adapted version of Arksey and O'Malley's framework for scoping reviews [1]. In this review we endeavored to “map” and summarize the existing, relevant scientific evidence, available in early 2020 on sleep health in the context of: 1) COVID-19, other pandemics and/or crises; 2) social isolation, loneliness or confinement; and 3) economic or financial adversity. We also aimed to identify new avenues for research to understand how sleep is impacted by global crises in order to guide the future development of public health interventions.

Methods

Using the Arksey and O'Malley's framework for scoping reviews, we followed the following steps: 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) selecting studies, 4) charting the data, 5) collating, summarizing and reporting results. In accordance the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [2], we undertook three parallel systematic reviews based on the following themes: 1) Sleep in times of crises; 2) Sleep and social isolation; and 3) Sleep and economic uncertainty. The three independent searches were conducted using different databases according to each theme. We searched these databases from inception to between May 30 and July 15, 2020, depending on the search. For each of the key concepts for each systematic search, a librarian (MDL) with expertise in systematic reviews developed a comprehensive list of its various synonyms, adapted to each database using a mix of terms from thesauri and keywords linked with appropriate Boolean and proximity operators. We performed our searches with a pool of various terms based on a combination of the key concepts previously identified across several electronic databases (see Table S1 for full search strategy). The study populations consisted of children, adolescents, adults and older adults. We did not apply any language restriction in the search strategy per se, but at the stage of screening for abstracts, we excluded the small numbers of articles published in other languages than English or French. Records were exported from each database into a master EndNote library, and duplicates were removed with Covidence.

Search 1: sleep and pandemics or other crises

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they satisfied the following criteria: they reported data on sleep variables in the context of “COVID-19”, “pandemics” or “crises” (see Table S1 for complete list of terms). In mid-July 2020, this search yielded 838 articles from CINAHL (EBSCO); 3748 articles from EMBASE (ELSEVIER); 2089 articles from Medline (OVID); 1022 articles from Psycinfo (OVID); 2583 articles from Web of science: Core Collection (Clarivate).

Search 2: sleep and social isolation

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they satisfied the following criteria: they reported data on sleep in the context of “social isolation”, “loneliness”, “confinement” or “social support” (see Table S1 for complete list of terms). On June 1, 2020, this search yielded 1468 articles from Medline (OVID); 3322 articles from EMBASE (ELSEVIER); 1174 articles from Psycinfo (OVID); 139 articles from Psychology and behavioral sciences collection (EBSCO); 1530 articles from Web of science: Core Collection (Clarivate).

Search 3: sleep and financial adversity

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they satisfied the following criteria: they reported data on sleep parameters in the context of “economic crisis”, “financial adversity”, or “job insecurity” (see Table S1 for complete list of terms). In mid-July 2020, this search yielded 343 articles from CINAHL (EBSCO); 1272 articles from EMBASE (ELSEVIER); 568 articles from Medline (OVID); 303 articles from Psycinfo (OVID); 732 articles from Web of science: Core Collection (Clarivate).

Screening

Screening processes were conducted using Covidence (covidence.org), an online platform that supports meta-analysis collaboration between multiple researchers. Two trained research assistants (JPD and XM) screened the title and abstract of each articles to determine which ones potentially met inclusion criteria. If the initial screening failed to result in consensus (i.e., a mismatch of yes/no/maybe), the final decision to include or exclude a study was made by another investigator (either GS or DP). Following this initial screening phase, the two research assistants (JPD and XM) conducted a more thorough full-text assessment to confirm study eligibility.

The inclusion criterion was being an epidemiological study reporting on sleep health parameters in the context of: 1) COVID-19, other pandemics and/or crises; 2) social isolation, loneliness or confinement; and 3) economic or financial adversity. The exclusion criteria for the studies were: 1) studies targeting special or clinical populations, with the exception of sleep disorders; 2) reviews or meta-analysis; 3) commentaries; 4) editorials; 5) dissertations; 6) poster presentations; 7) articles in languages other than French or English; 8) psychometric scale evaluation; 1) book sequence or chapters; j) animal studies; k) recommendations or guidelines. At this point, all recommendations to include or exclude studies were reviewed by two investigators (GS and DP).

Data extraction

The data extraction fields were determined through an iterative process. The study team identified the main areas of interest as follows: 1) study sample characteristics, 2) study design, 3) study measures, and 4) study outcomes. For each study, relevant data were extracted with customized data extraction forms. All final data were double entered into a Microsoft Excel database and included authors, title, year of publication, type of study (longitudinal, cross-sectional, interventional), study design (cohort, laboratory, survey, etc.), country, sample size, type of population (children, adolescents, adults, older adults), construct or exposure assessed, sleep measures used and summary findings. The data were extracted by JD and XM and checked by GS for accuracy and data quality.

Results

Search 1: COVID-19, other pandemics and/or crises

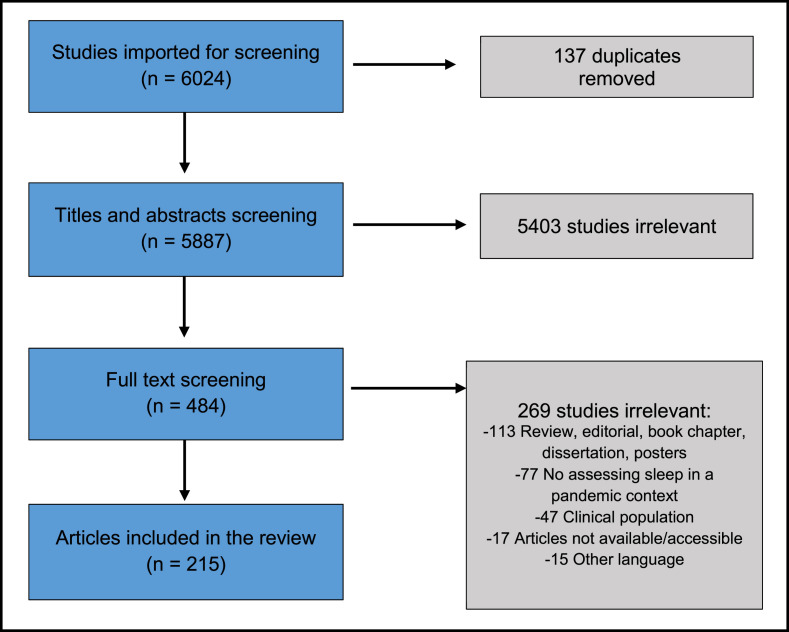

A total of 6024 entries were identified in our first original search, including 137 duplicates. During screening, 5403 studies were removed, leaving a total of 484 studies for full text review. After the additional exclusion of 269, 215 unique records reporting on sleep health parameters across different contexts of crises remained for data extraction (See Fig. 1 ). Table S2 and Tables S5–S7 group the final 215 studies in the following manner: sleep in the context of infectious outbreaks (79 studies), sleep in the context of natural disasters (78 studies); sleep in the context of terrorist attacks (22 studies); sleep in the context of war (13 studies); sleep in the context of anthropogenic disasters (23 studies). Only a handful studies relied on objective sleep measures (polysomnography or actigraphy).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of included studies search 1.

Sleep in the context of infectious outbreaks

Sleep in early COVID-19 studies in the general population

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, early reports primarily from China and Europe showed a large proportion of respondents reporting sleep problems. These epidemiological studies showed a large proportion (30–74%) of respondents reporting insomnia-like symptoms or sleep perturbations [∗[3], [4], ∗[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]] and sometimes longer sleep duration [12]. Shifts to later sleep time and/or longer sleep duration were especially prominent in young adults, adolescents and children [8,12,13] often concomitant with worse sleep quality [8,10,13,14]. Children and teens also had lower physical activity levels, spent less time outside, and presented more sedentary behaviors and increased leisure screen time [15], which contribute to worsened sleep. Conversely, children and youth who had the recommended amount of daily physical activity had no or little change in sleep duration since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [16].

Anxiety-related insomnia was more common in quarantined than non-quarantined youths [17]. The sleep of individuals who already had chronic insomnia before the onset of the pandemic deteriorated during the pandemic [18]. Of note, COVID-related insomnia was also associated with high suicide risk in adults [19]. Importantly, people who were directly threatened by the coronavirus had an elevated risk of insomnia [20,21]. Insomnia was indeed high in infected patients (68%) and in their family members or friends (48%) [22]. In patients with confirmed COVID-19, 89% reported sleep problems (severe in 52%) and 81% of individuals with suspected COVID-19 reported sleep problems (severe in 15%) [3].

Moderating/mediating factors in the association between COVID-19 and sleep in the general population

In general, more young adults reported disturbed sleep than did older individuals [3,10,13,21,23] and more women reported sleep problems than men [∗[3], [4], ∗[5], [6], [7],15,21,24,23]. Another important risk factor is prior psychological disposition. The increase in sleep difficulties was more prominent for people with a higher level of depression, anxiety, and stress symptomatology [13,25]. The mediation effect of anxiety on poor sleep during COVID-19 was stronger in people with low levels of self-esteem than in those with high levels of self-esteem [11]. Other risk factors for poor sleep during the early days of COVID-19 include socioeconomic status [3,5], education level [5], living in urban areas [5] and working in the medical field [5]. Conversely, social capital appeared to enhance sleep quality via reducing anxiety and stress [26].

Sleep in the general population in the context of other infectious disease outbreaks

We identified a handful of studies describing sleep health patterns in the context of two other infectious disease outbreaks: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) 2003 [[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]] and Ebola 2014 [34,35]. These studies showed that in residents of Amoy Garden, the first officially recognized site of the community SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, the insomnia rate reported via a questionnaire was 50% in affected residents, 56% in people with affected family members compared to 32.5% in other residents [32]. Another study, also relying on self-report, found that 25% of midlife women living elsewhere in Hong Kong during SARS reported restless sleep [33]. During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, up to 12% of American soldiers deployed reported symptoms compatible with insomnia compared to 4.9% at pre-deployment [35]. Finally, in individuals who contracted Ebola, 75% reported having “lost much sleep over worry” whereas 33.3% of people who had been in contact with a confirmed case reported this as a major problem [34].

Sleep in healthcare workers during COVID and other outbreaks

Among the diverse occupations studied, healthcare workers had the highest prevalence of poor sleep quality as measured with the PSQI [23]. The proportion of healthcare workers with symptoms of insomnia is high (18–75%) [23,[36], ∗[37], [38], [39], [40], [41]]. In pediatric doctors and nurses, anxiety levels (self-rating anxiety scale) were correlated moderately with the PSQI [42]. Medical and nursing staff with insomnia, as measured by the insomnia severity index (ISI), were suspected to have comorbid sleep apnea syndrome (based on pulse oximetry) attributable to stress [43]. The prevalence of insomnia varied depending on their degree of involvement with infected patients. It was higher in those working directly with infected patients [39,44], and thus particularly in nurses [37,38,40,41,44]. The same relationship between insomnia rate and proximity of the medical staff to infected patients was reported for the SARS [31] and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome [28] pandemics.

Moderating/mediating factors in the association between COVID and other pandemics and sleep in healthcare workers

A sex effect was found in healthcare workers: sleep impairments are higher in women than in men [37,40,44]. Another important factor in moderating the sleep quality in medical staff was the level of social support from the media, which was also significantly associated with perceived self-efficacy [45]. In fact, anxiety, stress, and self-efficacy were found to be mediating variables in the relationship between social support and sleep quality [45]. The feeling of not having enough personal protection equipment was also linked with higher prevalence of insomnia in healthcare workers [40]. An intervention study during the SARS pandemic demonstrated that a systematic prevention program for nursing staff, which included a series of in-service training, detailed work force allocation, adequate protective equipment, and the availability of a mental health team, decreased anxiety and depression levels and improved sleep quality on the PSQI [27]. Personalized psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures also helped decrease psychiatric symptoms and insomnia in workforce returning to work following the first COVID-19 confinement in China [46].

Sleep in the context of other types of crises

Our review of the literature identified 136 studies on sleep in the context of other types of crises, namely natural disasters, health disasters, wars (civilian populations) or terrorist attacks. The results of these studies are shown in supplementary Table S5–S7. As a whole, these studies showed poor sleep health during the acute phase of the crises, and some showed that poor sleep could persist for several years. Victims, close relative of victims and first responders seemed to be at a particularly high risk of adverse poor sleep health after exposure.

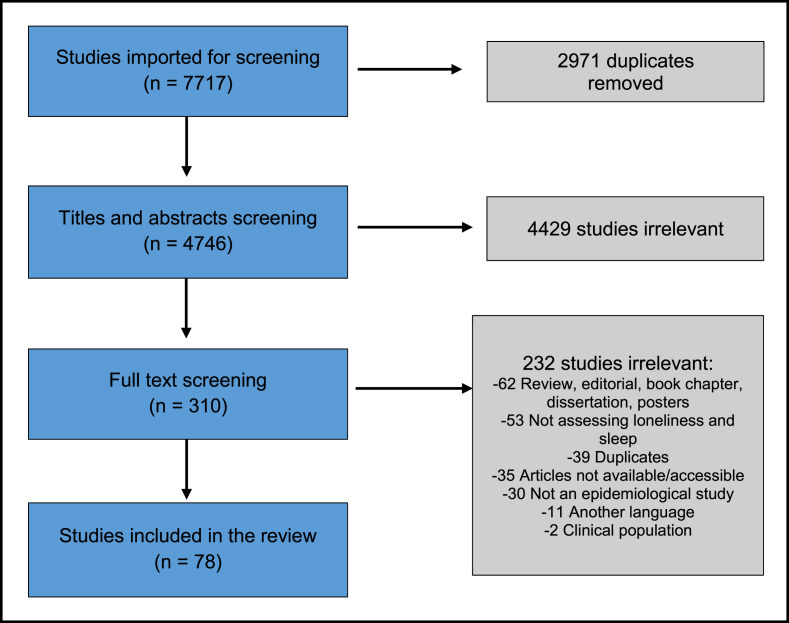

Search 2: sleep and social isolation or loneliness

A total of 7717 entries were identified in our second original search, including 2971 duplicates. During screening, 4436 studies were removed, leaving a total of 310 studies for full text review. After the additional exclusion of 232, 78 unique records examined the relationship between sleep and different domains of sociality and remained for data extraction (See Fig. 2 ). Table S3 groups the studies in the following manner: sleep and loneliness (42 studies); sleep and social isolation (15 studies); sleep and social support (20 studies); sleep and social cohesion (8 studies). Seven studies were included in more than one category of sociality outcomes, primarily by assessing sleep in the context of both loneliness and social isolation. Only a handful of studies (12 studies) relied on objective sleep measures, and these studies more often focused on children, adolescents or older adults, populations hypothesized to be more vulnerable to the impacts of sociality on health (and vice versa). Most of the studies came from high-income countries, highlighting existing gaps in knowledge in sleep health in low and middle-income countries.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of included studies search 2.

Sleep and loneliness or social isolation

Loneliness represents the discrepancy between an individual's desired and actual relationships. It is thus an unpleasant emotional interpretation of one's own social circumstances. Social isolation can be defined structurally as the absence of social interactions, contacts, and relationships with family, friends and neighbors on an individual level, and with “society” on a broader level. During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, several professional societies warned about the potential impact of social restrictions on health (and sleep). In our review, we only captured a small fraction of the array of studies that would later be published on the topic, as these studies were primarily published in the second half of 2020 (and forward). These epidemiological studies for example showed a high prevalence of loneliness, and a strong association between loneliness and sleep quality [47]. Our review on this topic will highlight the epidemiological evidence on different dimensions of sociality and sleep, the evidence that was available in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Studies have generally found a negative impact of loneliness and social isolation on sleep efficiency, sleep duration or sleep quality [[48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56]]. This negative influence has been shown with both objective (polysomnography [57] and actigraphy [48,58]) and subjective (questionnaires, surveys) [52,56,59] measures and observed across the life span, and independently of depression [57]. In older adults, the relationship seemed especially notable: a significant and inverse correlation between the degree of social isolation and the mean score of sleep quality has been reported [60]. One study differentiated between objective and perceived social isolation in older adults and found that, while the latter was strongly associated with sleep disturbances, objective social isolation was only weakly associated with sleep problems [61], the person's experience of social isolation or loneliness thus appearing central in this association. Interestingly, these results were independent of sociodemographic characteristics, body mass index, medical comorbidity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity, all of which are potential confounding factors. In an international survey of people suffering from insomnia, loneliness was among the top three reasons given by the participants for their insomnia [62].

A handful of studies on sleep evaluated health impacts of loneliness. One study found an association between loneliness and both sleep efficiency/quality and poorer antibody response to an influenza vaccine [63] while others suggested that sleep difficulties mediate the effect between loneliness and general health problems [52,57,64]. Two studies tested whether loneliness and social isolation have long-term negative consequences on sleep. Adolescents with relatively high levels of loneliness from middle childhood to pre-adolescence (8–11 years of age) were more likely to report trouble sleeping, taking longer to get to sleep, and waking up during the night than adolescents with low loneliness levels [50]. Similarly, in older adults, social isolation contributes to poor sleep quality 6 years later [56].

Depending on the studies, different confounding factors have been controlled for, but this did not affect the direction of the association observed between sleep and loneliness or social isolation. To that effect, differences in loneliness between monozygotic twins were reported to be significantly associated with within-twin pair differences in subjective sleep quality at age 18, i.e., the lonelier twin reported worse overall sleep quality on the PSQI [65], thus obviating the general and various influences of the familial milieu.

Moderating/mediating factors of the relationship between loneliness or social isolation and sleep

Although it can be argued from the numerous studies previously cited that loneliness seems to directly affect sleep quality, other studies claim that the effect of loneliness on sleep is mediated by depression [55] or by stress [51], anxiety and rumination [66]. However, several studies specifically controlled for depression [50,58] and observed a persisting negative association between loneliness and sleep quality nonetheless. In addition, a sex effect was found for the influence of loneliness or social isolation on sleep; this relationship being stronger in men than in women [51,67].

Loneliness as a mediator or moderator in the relationship between stress and sleep quality

In addition to its direct effects on sleep, loneliness was also shown to be a strong mediator of the relationship between stress and poor sleep quality especially in the elderly [59] and a significant moderator in the bidirectional association between daily stress and objective sleep duration and latency [48]. A study on paramedics also reported that individuals with low levels of social support had poor sleep quality in the face of high occupational stress whereas those who had high levels of support did not show significant effects of occupational stress on sleep [68]. Socially-isolated individuals also have much greater odds of having insomnia when living in neighborhoods with low employment rates than socially-connected individuals [69].

Sleep and social cohesion

The neighborhood social environment is also associated with sleep health. A lower neighborhood social cohesion, defined as the level of solidarity and connectedness shared within a group of people living in proximity, was shown to have a negative impact on objectively-measured [70,71] and self-reported [67,72,73] sleep in children, adults and older adults. Children exposed to high levels of neighborhood social fragmentation experienced poor sleep efficiency and a shorter sleep duration on actigraphy [70]. Studies in adults found that those who reported living in a neighborhood with low social cohesion were more likely to report shorter sleep duration [67,71,72,74] and poor sleep quality [72,74], whereas in neighborhoods with medium to high levels of social cohesion, individuals reported longer sleep duration and higher sleep efficiency [73]. In older adults, a relationship was found between a positive neighborhood social environment and early timing of sleep and longer sleep duration [71].

Social support has a protective effect on sleep

One of the protective factors for the negative effects of confinement on sleep is social support or social capital. Social support can be defined as the experience of being loved, cared for, esteemed, and part of a social network characterized by mutual assistance and obligation. Social capital is defined as a collection of actual or potential resources that include social trust, belonging, and participation. Increased levels of social capital were positively associated with increased quality of sleep during COVID-19 self-isolation [75]. However, the combination of high anxiety and stress reduced the positive effects of social capital on sleep quality [75].

Good social support is positively correlated with several indicators of high-quality sleep such as duration, efficiency, latency and quality [76] or lower PSQI score [77]. Interestingly, people with a high level of social exposure are found to have higher amounts of slow-wave sleep than people with lower social exposure [78]. In older adults with insomnia or without insomnia, higher social support is associated with better perceived sleep quality, shorter sleep latencies on the Pittsburgh sleep diary [79] or less time spent awake during the night as measured by actigraphy [79]. In studies that divided social support into subcategories, emotional support was the component most strongly associated with better self-reported sleep outcomes [80]. However, it is important to mention that some studies found no effect of social support on objective measures of sleep [81,82].

In general, social support, in counteracting loneliness, has beneficial effects on both sleep, general health [52] and depression [49]. Inversely, a low social support in already highly stressful or traumatic situations can aggravate the sleep difficulties. For example, lack of social support showed a stronger association with long-lasting sleep difficulties than did non-modifiable or hardly modifiable consequences caused directly by an earthquake [80].

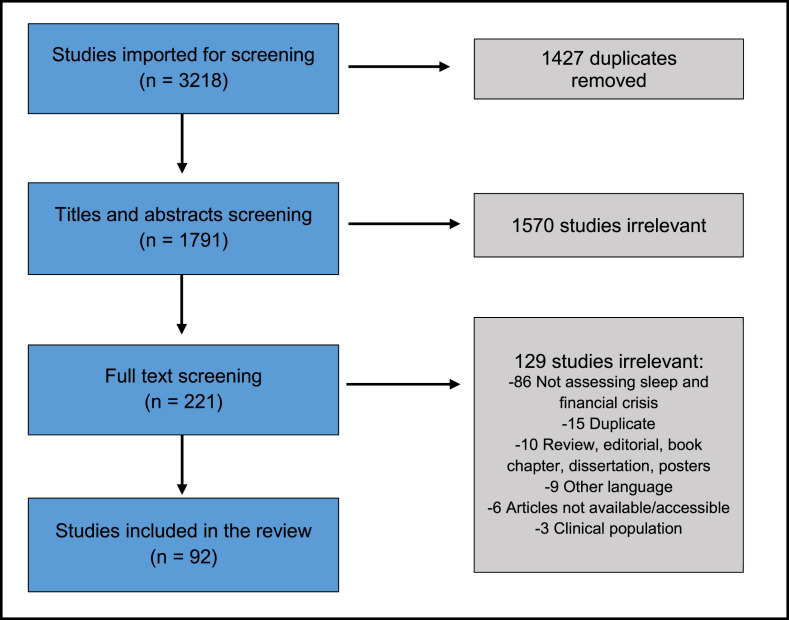

Search 3: sleep and economic uncertainty, financial adversity, or food/job insecurity

A total of 3218 entries were identified in our third original search, including 1427 duplicates. During screening, 1570 studies were removed, leaving a total of 221 studies for full text review. After the additional exclusion of 129 studies, 92 unique records examining the relationship between sleep health and different aspects of economic difficulties remained for data extraction (see Fig. 3 ). Table S4 groups the studies in the following manner: sleep and financial difficulties (33 studies); sleep and job insecurity (23 studies); sleep and economic crisis (14 studies); sleep and food insecurity (21 studies). A single study was included in more than one category of economic outcome. In the 92 studies included in our review, six used polysomnography or actigraphy and 32 used a validated questionnaire to measure sleep outcomes. The majority of the studies (n = 82) measured the effect of economic difficulties on sleep health in adults, 10 studies were conducted in children and adolescents.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of included studies search 3.

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, an abrupt stop in the global economic activity led to many countries to implement economic measures aimed at mitigating the economic and financial consequences of a poor economic outlook. In our review, we only captured a small fraction of the array of studies that would later be published on the topic, as these studies were primarily published in the second half of 2020 (and forward). These epidemiological studies for example would later show a close link between financial stress and poor sleep [83]. Our review on this topic will highlight the epidemiological evidence on different dimensions of financial vulnerability and sleep, evidence that was available in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sleep and economic uncertainty or financial adversity

Economic or financial adversity refers to having insufficient financial resources to adequately meet one's household's needs. Several studies, including large cohort or population-based studies, have shown a relationship between high level of financial adversity and lower sleep efficiency, poorer sleep quality or insomnia with both objective [[84], [85], [86]] and subjective [86,87] measures. An international survey of people suffering from insomnia reported that financial strain was amongst the top five reasons evoked by participants as the cause of their insomnia [62]. Similarly, focus groups identified economic insecurity as the main cause of their difficulty sleeping: “No money, no car, no job, no sleep” [88]. In addition, participants mentioned economic insecurity as the main cause of sleep disparities in their community [88]. Indeed, the differences in sleep duration often reported between ethnic groups (shorter in African Americans and Hispanics than in Caucasians) was shown to be strongly mediated by financial hardship [89]. African American children who are worse off financially had more sleep/wake problems than those with more financial resources whereas no such effects were found for European American children [84]. Another study found, on the contrary, that financial strain has similar effects on sleep, independent of race (including African Americans) [86]. Finally, a strong positive association was found between over-indebtedness and self-reported sleep onset and maintenance difficulties and sleep medication use, which was independent of conventional socioeconomic measures [90].

Familial economic hardship also affect adolescents’ subjective sleep quality [91], and perceived economic discrimination has been identified as a strong mediator [91]. In infants and children, familial economic difficulties are mainly linked to difficulties falling asleep or short sleep [84,92] and the adoption by parents of suboptimal sleep practices for their children [92]. One study found that financial strain induced greater night-to-night variability in polysomnography characteristics in women [93].

Sleep and food insecurity

Studies investigating more specifically food insecurity in adults found objectively shorter sleep duration and poorer sleep efficiency [94] or poorer subjective sleep quality [95,96] or quantity [96]. Moreover, poor sleep quality and quantity was found to partially mediate the relationship between food insecurity and obesity across several ethnicities and races [96]. The link between food insecurity and sleep in children and adolescents is not as clear but some studies report a connection between food insecurity and insufficient sleep in children and adolescents [97,98]. Finally, one study reported that 70% of mothers in food-insecure households did not implement a nightly bedtime routine for their toddlers [99]. A bedtime routine increases sleep duration through a decrease in nocturnal awakenings [99].

Sleep and job insecurity or threat of unemployment

Job insecurity is yet another important factor to consider. Young adults exposed to prolonged precarious employment report insufficient sleep [100]. Job or salary insecurity is associated to subjective sleep problems [101,102] or insufficient sleep [103]. However, data from a survey conducted in 31 European countries suggest that it is the subjective employment insecurity rather than the objective precarity per se that relates to sleep disturbances [104]. Men report more work-related sleep problems than women in general [105] although this sex effect is reduced in countries where there is more sex parity in work-family role obligations [105]. Even extensive organizational changes at work can cause sleep disturbances [106].

Unemployment is associated with increased difficulty falling asleep and sleep maintenance problems [107,108] and to reporting a sleeping problem lasting more than 6 months [109]. Long-term unemployment was associated with a trajectory of decreasing self-reported sleep duration over 5 years [110]. Expectedly, in an economic recession, it is more the prospectively unemployed individuals, especially the blue-collar workers, who report suffering more from insomnia, fatigue, parasomnias and who used more hypnotics than the continuously employed people [111]. The perceived personal impact of a crisis is also key in this relationship [107]. The increase in sleep disturbances and nightmares can be seen years after the financial crisis has started [112]. The probability of sleep problems and nonrestorative sleep increases with the seriousness or number of material hardships, or the persistence of economic difficulties [113].

Sleep and local or global economic vulnerability

In addition to personal economic vulnerability and regardless of personal characteristics, local economic predicaments such as areas with high unemployment rates can negatively influence self-reported sleep duration [114]. Not surprisingly, however, the correlation between poor local economic conditions and short sleep duration is even stronger for economically vulnerable individuals [114]. However, one large US population-based study found on the contrary that higher state unemployment rates are associated with more sleep time when controlling the mediating effects of the respondent's own employment status and household income [115]. Similarly, a five-percentage point increase in unemployment rate in Canada was associated with three more hours of sleep per week for both men and women [116]. During the Iceland economic crisis of 2008, an increase in the proportion of people reporting getting the recommended number of hours of sleep was seen and this effect was greater in the working age population [117]. Prescriptions for sleep aids and benzodiazepines increased in the US following the economic recession of 2008 and this increase was more marked for men compared to women [118]. On the other hand, the number of patients visiting a sleep clinic went down during an economic crisis and people requiring a continuous positive airway pressure machine were less likely to get one [119].

Moderating/mediating/protective factors of the relationship between economic uncertainty and sleep

One might believe that age would be a moderating factor in the relation between economic uncertainty and sleep. A longitudinal study showed that the proportion of sleep problems and insufficient sleep duration related to the 2008 recession has increased mainly for young men (20–40 years) in France [120]. A United Kingdom longitudinal study of two nationally representative cohorts showed that sleep loss because of worrying usually declines with age (from age 50 onward), but not as much in an economic turndown [121]. Indeed, financial strain had a significant influence on sleep disturbances in the elderly (61–85 years), even after adjusting for factors known to impact sleep in late-life such as age, sex, mental and physical health [85]. Of course, in times of crises, a common denominator underlying the various ordeals is stress and unemployment can then add up and exacerbate sleep outcomes. For example, following the fireworks storage facility explosions in Enschede (Netherlands) in 2000, unemployed individuals suffered from worse sleeping difficulties and higher levels of post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression up to 4 years later than employed individuals.[122] Perceived stress was found to mediate relations between both income-to-needs ratio and subjective sleep problems in women [123]. On the other hand, a longer duration of sleep appears to be a protective factor against the development of future anxiety symptoms due to job insecurity or organizational injustice in otherwise healthy employees [124].

Discussion

In this review, based on the existing evidence available in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, we systematically uncovered, collated and summarized key findings on potential circumstantial ways by which the COVID-19 pandemic may directly or indirectly affect sleep health. Overall, we identified that states of crises (characterized by stress, anxiety, loss of loved ones and/or material losses), social isolation and loneliness, as well as financial stress, job or food insecurity, are all associated with poor sleep health. Conversely, greater social support and social cohesion are associated with better sleep health, highlighting the potential positive role that our communities play at fostering healthy sleep. Government-imposed stay-at-home orders, tele-work and tele-school, and enforced social distancing may likely have an impact in our sleep not only through heightened stress but also as social and environmental cues play an important role in entraining our internal biological clocks. The experienced challenges during these unprecedented times may likely differ in intensity depending on the individuals’ age, sex, socioeconomic status, family circumstances, psychological predisposition and occupation. Taken together, our findings suggest that crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic likely posits compounding adverse sleep health impacts that warrant public health attention. Despite some promising evidence on the efficacy of web-based sleep intervention applications for health care workers, [125] our review did not identify any study aimed to test rapid deployment of sleep interventions in either healthcare workers or in the general population, suggesting lack of preparedness.

Research agenda: State of crisis and sleep

Our review of the evidence shows lack of consistent good quality data on what sleep looks like during different crises. Most studies aimed to compare the prevalence of poor sleep of those exposed compared to non-exposed, rather than to fully capture the array of contextual factors that may be shaping sleep patterns during the acute phase of a crisis, as well as in its aftermath. Even in the context of lack of prospective studies at the acute time of these crises, given how common sleep tracking devices are, retrospective data could be used to understand sleep patterns and practices that were adaptive in the contexts of crises, in particularly among frontline workers and other populations at risk of poor sleep. Identifying behaviour and practices that are associated with healthy sleep in contexts of crises may help develop crises management responses that include promoting better sleep and sufficient rest. Sleep problems were already highly prevalent globally before COVID-19,[126] and those who were not sleeping sufficiently may have been at an increased risk of adverse mental health outcomes [127] An important unanswered question is the extent to which sleep satiation (i.e., sleeping sufficiently) prior to a crisis leads to better crisis coping and management. In other words, is a better-slept society able to navigate a crisis better than a sleep deprived society? Increased sleep satiation is associated with better cognitive processing, decision-making and emotional regulation, improved energy and mood, all of which likely underlie performance and coping [[128], [129], [130]].

Research agenda: Sociality and sleep

Social factors, such as social isolation or loneliness, are associated with inadequate sleep and increased risk of poor sleep health in the general population. Overall, evidence using objective sleep measures is lacking, in particular in adults, suggesting the need for better studies that allow us to evaluate the independent association between these social factors and sleep, as well as its directionality. Further, the potential impacts of emerging widespread use of virtual technology in the context of tele-school, tele-work and tele-socialization is likely to change the way we learn, work and socialize in years to come, prompting new questions on their impacts on sleep health. Some of these behaviors may be adaptive such as normalizing virtual gatherings as socially acceptable, and thus fostering connection, the capacity to take classes at a the preferred (circadian) time during online schooling or decreased commuting time. Conversely, increased screen time at home, prolonged social isolation, lack of outdoor time or changes in diet may have negative consequences on sleep health. Being satisfied with one's social life and being active are protective factors against insomnia [131]. This underlines the importance of intervention programs on enhancing social support for behavior change and sleep health, particularly in vulnerable populations. Other important considerations relate to family dynamics, and the reconfiguration of the home environment to accommodate both work and schooling demands. In this particular context, predicaments related to access to sufficient space at home, childcare and outdoor activities may exacerbate sleep health related problems.

Research agenda: Economic uncertainty and sleep

Our review of the evidence shows that job insecurity, fear of losing a job, food insecurity and financial stress are associated with poor sleep health. However, only a handful of studies relied on objective sleep measures. Several economic actions were put in place across the globe with the goal of dampening the economic and financial hit caused in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. These measures aimed at supporting the economy and specially to help individuals in precarious situations could have a positive impact on sleep health, yet still this needs to be investigated.

Opportunities for intervention and public policy

Our review of the evidence highlighted several potential pathways by which states of crises may affect sleep health. Our review also highlights the need to develop and deploy interventions aimed at promoting better sleep health in times of crises. Along these lines, measures that target social and/or financial factors that are closely link to different dimensions of sleep health are further warranted. In the context of COVID-19, social interventions for example could be aimed at fostering social cohesion, providing social support, increasing perceived safety, promoting social connection and preventing social isolation. In the context of COVID-19, financial interventions for example could target financial stress by providing tax breaks and/or universal (like) basic income or could target threat of unemployment by providing wage subsidies to employers to prevent layoffs. Other interventions that may improve both social and financial means may be related to providing support for childcare. The wide range of policies and measures taken by different governments may serve as quasi-experiments to help us identify policies that lead to better sleep health. Additionally, the study of these policies and their link to sleep health could help us identify groups that benefitted the most (and the least) and inform future development of public health interventions.

Limitations

The heterogeneous group of studies identified in this review carries several limitations to consider. The first limitation is that very few studies used an objective measure of sleep; the majority of studies used either validated questionnaires, such as the PSQI, non-validated questionnaires or only one or a few questions. Therefore, a response bias can easily be introduced which can overestimate convergent validity: worse conditions (e.g., loneliness, financial strain) = worse sleep. Second, studies based on open surveys (volunteered self-report) have a selection bias, in particular when lacking sampling plans, quotas or weights. Third, key concepts, such as social support, loneliness, financial uncertainty or job insecurity, are defined very differently in the various studies, affecting comparability between studies. Fourth, since the majority of studies are observational (cross-sectional), the relationships identified should not be readily interpreted as causal relationships. Fifth, only a handful of studies were conducted in low- and middle-income countries, decreasing the generalizability of our findings. Finally, very few studies had pre-pandemic sleep data. Despite all those limitations, there is enough evidence of the negative impacts on sleep resulting from the various characteristics of the current and past crises (stress, social isolation, economic hardship) to justify concrete actions to protect the population's sleep.

Conclusions

Crises, as well as associated social and economic adverse circumstances are associated with both short term, and long term adverse negative sleep consequences. Efforts to understand the aspects of sleep affected by crises and their underlying pathways, and to develop interventions to alleviate sleep health impacts of crises are warranted.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Practice points.

-

•

States of crises (characterized by stress, anxiety, loss of loved ones and/or material losses), social isolation and loneliness, and financial stress or food insecurity, are all associated with adverse sleep health outcomes.

-

•

Clinicians should consider financial and social factors as potential sources of (or contributors to) deficient sleep in their patients.

-

•

Public health measures aimed at decreasing individuals' financial and/or social burden during a crisis may lead to improved sleep.

Footnotes

The most important references are denoted by an asterisk.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101545.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Multimedia component 2

Multimedia component 3

Multimedia component 4

Multimedia component 5

Multimedia component 6

References∗

- 1.Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck F., Leger D., Fressard L., Peretti-Watel P., Verger P. Covid-19 health crisis and lockdown associated with high level of sleep complaints and hypnotic uptake at the population level. J Sleep Res. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jsr.13119. [No-Specified] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demir Ü.F. The effect of covid-19 pandemic on sleeping status. J Surg & Med (JOSAM) 2020;4:334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Fu W., Wang C., Zou L., Guo Y., Lu Z., Yan S., Mao J. Psychological health, sleep quality, and coping styles to stress facing the covid-19 in Wuhan, China. Translational Psychiatry. 2020;10:225. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00913-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gualano M.R., Lo Moro G., Voglino G., Bert F., Siliquini R. Effects of covid-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartley S., Colas des Francs C., Aussert F., Martinot C., Dagneaux S., Londe V., et al. [The effects of quarantine for SARS-CoV-2 on sleep: an online survey]. Les effets de confinement SARS-CoV-2 sur le sommeil : enquete en ligne au cours de la quatrieme semaine de confinement. 2020;46:S53–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marelli S., Castelnuovo A., Somma A., Castronovo V., Mombelli S., Bottoni D., et al. Impact of covid-19 lockdown on sleep quality in university students and administration staff. J Neurol. 2020;268:8–15. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10056-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton R., To Q.G., Khalesi S., Williams S.L., Alley S.J., Thwaite T.L., et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan S., Liao Z.X., Huang H.J., Jiang B.Y., Zhang X.Y., Wang Y.W., et al. Comparison of the indicators of psychological stress in the population of Hubei province and non-endemic provinces in China during two weeks during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in february 2020. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2020;26:10. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao X., Lan M., Li H., Yang J. Perceived stress and sleep quality among the non-diseased general public in China during the 2019 coronavirus disease: a moderated mediation model. Sleep Med. 2020;77:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Renzo L., Gualtieri P., Pivari F., Soldati L., Attinà A., Cinelli G., et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during covid-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med. 2020;18:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cellini N., Canale N., Mioni G., Costa S. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Sleep Res. 2020;29:e13074. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaparounaki C.K., Patsali M.E., Mousa D.P.V., Papadopoulou E.V.K., Papadopoulou K.K.K., Fountoulakis K.N. University students' mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatr Res. 2020:290. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore S.A., Faulkner G., Rhodes R.E., Brussoni M., Chulak-Bozzer T., Ferguson L.J., et al. Impact of the covid-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of canadian children and youth: a national survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2020;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00987-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerrero M.D., Vanderloo L.M., Rhodes R.E., Faulkner G., Moore S.A., Tremblay M.S. Canadian children's and youth's adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic: a decision tree analysis. J Sport and Health Sci. 2020;9:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saurabh K., Ranjan S. Compliance and psychological impact of quarantine in children and adolescents due to covid-19 pandemic. Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:532–536. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang L., Yu Z., Xu Y., Liu W., Liu L., Mao H. Mental status of patients with chronic insomnia in China during COVID-19 epidemic. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020937716. 20764020937716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caballero-Domínguez C.C., Jiménez-Villamizar M.P., Campo-Arias A. Suicide risk during the lockdown due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Colombia. Death Stud. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1784312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J., Feng X.L., Wang X.H., van Ijzendoorn M.H. Coping with covid-19: exposure to covid-19 and negative impact on livelihood predict elevated mental health problems in Chinese adults. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin L.-Y., Wang J., Ou-Yang X.-Y., Miao Q., Chen R., Liang F.-X., Zhang Y.-P., Tang Q., Wang T. The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Lu Z.-A., Que J.-Y., Huang X.-L., Liu L., Ran M.-S., Gong Y.-M., Yuan K., Yan W., Sun Y.-K., Shi J., Bao Y.-P., Lu L. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in china during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020;vol. 3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Zhao N. Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Who will be the high-risk group? Psychology. Health & Med. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antunes R., Frontini R., Amaro N., Salvador R., Matos R., Morouco P., et al. Exploring lifestyle habits, physical activity, anxiety and basic psychological needs in a sample of Portuguese adults during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amerio A., Bianchi D., Santi F., Costantini L., Odone A., Signorelli C., et al. Covid-19 pandemic impact on mental health: a web-based cross-sectional survey on a sample of Italian general practitioners. Acta Biomed : Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91:83–88. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao H., Zhang Y., Kong D., Li S., Yang N. Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 Days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in january 2020 in China. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res : Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.923921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen R., Chou K.-R., Huang Y.-J., Wang T.-S., Liu S.-Y., Ho L.-Y. Effects of a SARS prevention programme in Taiwan on nursing staff's anxiety, depression and sleep quality: a longitudinal survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S.M., Kang W.S., Cho A.-R., Kim T., Park J.K. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatr. 2018;87:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maunder R., Hunter J., Vincent L., Bennett J., Peladeau N., Leszcz M., et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 sars outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J): Can Med Assoc J. 2003;168:1245–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAlonan G.M., Lee A.M., Cheung V., Cheung C., Tsang K.W.T., Sham P.C., et al. Immediate and sustained psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care workers. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Rev Canad Psychiatr. 2007;52:241–247. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su T.-P., Lien T.-C., Yang C.-Y., Su Y.L., Wang J.-H., Tsai S.-L., et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and psychological adaptation of the nurses in a structured SARS caring unit during outbreak: a prospective and periodic assessment study in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S., Chan L.Y., Chau A.M., Kwok K.P., Kleinman A. The experience of SARS-related stigma at Amoy Gardens. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2038–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu H.Y.R., Ho S.C., So K.F.E., Lo Y.L. Short Communication: the psychological burden experienced by Hong Kong midlife women during the SARS epidemic. Stress and Health. J Int Soc Invest Stress. 2005;21:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammed A., Sheikh T.L., Gidado S., Poggensee G., Nguku P., Olayinka A., et al. An evaluation of psychological distress and social support of survivors and contacts of ebola virus disease infection and their relatives in lagos, Nigeria: a cross sectional study--2014. BMC Publ Health. 2015;15:824. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2167-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sipos M.L., Kim P.Y., Thomas S.J., Adler A.B.U.S. Service member deployment in response to the ebola crisis: the psychological perspective. Mil Med. 2018;183:e171–e178. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usx042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jahrami H., BaHammam A.S., AlGahtani H., Ebrahim A., Faris M., AlEid K., Saif Z., Haji E., Dhahi A., Marzooq H., Hubail S., Hasan Z. The examination of sleep quality for frontline healthcare workers during the outbreak of COVID-19. Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11325-020-02135-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N., Wu J., Du H., Chen T., Li R., Tan H., Kang L., Yao L., Huang M., Wang H., Wang G., Liu Z., Hu S. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open. 2020;vol. 3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shechter A., Diaz F., Moise N., Anstey D.E., Ye S., Agarwal S., et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2020;66:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S., Xie L., Xu Y., Yu S., Yao B., Xiang D. 2020. Sleep disturbances among medical workers during the outbreak of COVID-2019. Occupational medicine. Oxford, England. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W.R., Wang K., Yin L., Zhao W.F., Xue Q., Peng M., et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89:242–250. doi: 10.1159/000507639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Y., Yang Y., Shi T., Song Y., Zhou Y., Zhang Z., et al. Prevalence and demographic correlates of poor sleep quality among frontline health professionals in liaoning province, China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:520. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng F.F., Zhan S.H., Xie A.W., Cai S.Z., Hui L., Kong X.X., et al. Anxiety in Chinese pediatric medical staff during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019: a cross-sectional study. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9:231–236. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.04.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhuo K.M., Gao C.Y., Wang X.H., Zhang C., Wang Z. Stress and sleep: a survey based on wearable sleep trackers among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the COVID-19 pandemic. General psychiatry. 2020;33:6. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhan Y., Liu Y., Liu H., Li M., Shen Y., Gui L., et al. Factors associated with insomnia among Chinese frontline nurses fighting against covid-19 in wuhan: a cross-sectional survey. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28:1525–1535. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao H., Zhang Y., Kong D., Li S., Yang N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in january and february 2020 in China. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.923549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan W., Hao F., McIntyre R.S., Jiang L., Jiang X., Zhang L., et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Groarke J.M., Berry E., Graham-Wisener L., McKenna-Plumley P.E., McGlinchey E., Armour C. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. PloS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doane L.D., Thurston E.C. Associations among sleep, daily experiences, and loneliness in adolescence: evidence of moderating and bidirectional pathways. J Adolesc. 2014;37:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu Y.Y., Ji X.W. Intergenerational relationships and depressive symptoms among older adults in urban China: the roles of loneliness and insomnia symptoms. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2020;28:1310–1322. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris R.A., Qualter P., Robinson S.J. Loneliness trajectories from middle childhood to pre-adolescence: impact on perceived health and sleep disturbance. J Adolesc. 2013;36:1295–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Segrin C., Burke T.J. Loneliness and sleep quality: dyadic effects and stress effects. Behav Sleep Med. 2015;13:241–254. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2013.860897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segrin C., Domschke T. Social support, loneliness, recuperative processes, and their direct and indirect effects on health. Health Commun. 2011;26:221–232. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.546771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Segrin C., Passalacqua S.A. Functions of loneliness, social support, health behaviors, and stress in association with poor health. Health Commun. 2010;25:312–322. doi: 10.1080/10410231003773334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tavernier R., Willoughby T. A longitudinal examination of the bidirectional association between sleep problems and social ties at university: the mediating role of emotion regulation. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:317–330. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wakefield J.R.H., Bowe M., Kellezi B., Butcher A., Groeger J.A. Longitudinal associations between family identification, loneliness, depression, and sleep quality. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25:1–16. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu B., Steptoe A., Niu K., Ku P.W., Chen L.J. Prospective associations of social isolation and loneliness with poor sleep quality in older adults. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:683–691. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cacioppo J.T., Hawkley L.C., Berntson G.G., Ernst J.M., Gibbs A.C., Stickgold R., et al. Do lonely days invade the nights? Potential social modulation of sleep efficiency. Psychol Sci : J Am Psychol Soc / APS. 2002;13:384–387. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurina L.M., Knutson K.L., Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T., Lauderdale D.S., Ober C. Loneliness is associated with sleep fragmentation in a communal society. Sleep. 2011;34:1519–1526. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aanes M.M., Hetland J., Pallesen S., Mittelmark M.B. Does loneliness mediate the stress-sleep quality relation? the Hordaland Health Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:994–1002. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zohre M., Ali N. Surveying the relationship between the social isolation and quality of sleep of the older adults in Barn-based Elderly Care Centers in 2017. World Family Medicine. 2018;16:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cho J.H.-J., Olmstead R., Choi H., Carrillo C., Seeman T.E., Irwin M.R. Associations of objective versus subjective social isolation with sleep disturbance, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23:1130–1138. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1481928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allaert F.A., Urbinelli R. Sociodemographic profile of insomniac patients across national surveys. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:3–7. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pressman S.D., Cohen S., Miller G.E., Barkin A., Rabin B.S., Treanor J.J., et al. Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychol. 2005;24:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peltzer K., Pengpid S. Loneliness correlates and associations with health variables in the general population in Indonesia. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;vol. 13 doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0281-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews T., Danese A., Gregory A.M., Caspi A., Moffitt T.E. Sleeping with one eye open: loneliness and sleep quality in young adults. Psychol Med. 2017;47:2177–2186. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zawadzki M.J., Graham J.E., Gerin W. Rumination and anxiety mediate the effect of loneliness on depressed mood and sleep quality in college students. Health Psychol. 2013;32:212–222. doi: 10.1037/a0029007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Win T., Yamazaki T., Kanda K., Tajima K., Sokejima S. Neighborhood social capital and sleep duration: a population based cross-sectional study in a rural Japanese town. BMC Publ Health. 2018;18:343. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pow J., King D.B., Stephenson E., DeLongis A. Does social support buffer the effects of occupational stress on sleep quality among paramedics? A daily diary study. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22:71–85. doi: 10.1037/a0040107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Riedel N., Fuks K., Hoffmann B., Weyers S., Siegrist J., Erbel R., et al. Insomnia and urban neighbourhood contexts--are associations modified by individual social characteristics and change of residence? Results from a population-based study using residential histories. BMC Publ Health. 2012;12:810. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bagley E.J., Fuller-Rowell T.E., Saini E.K., Philbrook L.E., El-Sheikh M. Neighborhood economic deprivation and social fragmentation: associations with children's sleep. Behav Sleep Med. 2018;16:542–552. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2016.1253011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnson D.A., Simonelli G., Moore K., Billings M., Mujahid M.S., Rueschman M., et al. The neighborhood social environment and objective measures of sleep in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2017;40 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson D.A., Lisabeth L., Hickson D., Johnson-Lawrence V., Samdarshi T., Taylor H., et al. The social patterning of sleep in african Americans: associations of socioeconomic position and neighborhood characteristics with sleep in the jackson heart study. Sleep. 2016;39:1749–1759. doi: 10.5665/sleep.6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murillo R., Ayalew L., Hernandez D.C. The association between neighborhood social cohesion and sleep duration in latinos. Ethnicity & Health. 2019 doi: 10.1080/13557858.2019.1659233. [No-Specified] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Young M.C., Gerber M.W., Ash T., Horan C.M., Taveras E.M. Neighborhood social cohesion and sleep outcomes in the native Hawaiian and pacific islander national health interview survey. Sleep. J Sleep and Sleep Disorders Res. 2018;41:1–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xiao H., Zhang Y., Kong D., Li S., Yang N. Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in January 2020 in China. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.923921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jin Y., Ding Z., Fei Y., Jin W., Liu H., Chen Z., et al. Social relationships play a role in sleep status in Chinese undergraduate students. Psychiatr Res. 2014;220:631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu X., Liu C., Tian X., Zou G., Li G., Kong L., et al. Associations of perceived stress, resilience and social support with sleep disturbance among community-dwelling adults. Stress and Health. J Int Soc Investigation Stress. 2016;32:578–586. doi: 10.1002/smi.2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Butt M., Ouarda T., Quan S.F., Pentland A., Khayal I. Technologically sensed social exposure related to slow-wave sleep in healthy adults. Sleep and Breathing. 2015;19:255–261. doi: 10.1007/s11325-014-1005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel W.M., Buysse D.J., Monk T.H., Begley A., Hall M. Does social support differentially affect sleep in older adults with versus without insomnia? J Psychosom Res. 2010;(69):459. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S., et al. Teikyo Ishinomaki Research G, Babson. Implications for social support on prolonged sleep difficulties among a disaster-affected population: Second report from a cross-sectional survey in Ishinomaki, Japan. PLoS One. 2015:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130615. [Electronic Resource] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chung J. Social support, social strain, sleep quality, and actigraphic sleep characteristics: evidence from a national survey of US adults. Sleep Health. 2017;3:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Paulsen V.M., Shaver J.L. Stress, support, psychological states and sleep. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:1237–1243. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90038-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Robillard R., Saad M., Edwards J., Solomonova E., Pennestri M.H., Daros A., et al. Social, financial and psychological stress during an emerging pandemic: observations from a population survey in the acute phase of COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.El-Sheikh M., Bagley E.J., Keiley M., Rimore-Staton L., Buckhalt J.A., Chen E. Economic adversity and children's sleep problems: multiple indicators and moderation of effects. Health Psychol. 2013;32:849–859. doi: 10.1037/a0030413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hall M., Buysse D.J., Nofzinger E.A., Reynolds I.C.F., Thompson W., Mazumdar S., et al. Financial strain is a significant correlate of sleep continuity disturbances in late-life. Biol Psychol. 2008;77:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hall M.H., Matthews K.A., Kravitz H.M., Gold E.B., Buysse D.J., Bromberger J.T., et al. Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: the SWAN Sleep Study. Sleep. 2009;32:73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beck F., Guignard R., Léger D. Life events and sleep disorders: major impact of precariousness and undergone violence. Medecine du Sommeil. 2010;7:146–155. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sonnega J., Sonnega A., Kruger D. The city doesn't sleep: community perceptions of sleep deficits and disparities. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16:13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matthews K.A., Hall M.H., Lee L., Kravitz H.M., Chang Y., Appelhans B.M., et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in women's sleep duration, continuity, and quality, and their statistical mediators: study of women's health across the nation. Sleep. 2019;42 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Warth J., Puth M.T., Tillmann J., Porz J., Zier U., Weckbecker K., et al. Over-indebtedness and its association with sleep and sleep medication use. BMC Publ Health. 2019;19:15. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bao Z., Chen C., Zhang W., Zhu J., Jiang Y., Lai X. Family economic hardship and Chinese adolescents' sleep quality: a moderated mediation model involving perceived economic discrimination and coping strategy. J Adolesc. 2016;50:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Duh-Leong C., Messito M.J., Katzow M.W., Tomopoulos S., Nagpal N., Fierman A.H., et al. Academic Pediatrics; 2020. Material hardships and infant and toddler sleep duration in low-income hispanic families. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zheng H., Sowers M., Buysse D.J., Consens F., Kravitz H.M., Matthews K.A., Owens J.F., Gold E.B., Hall M. Sources of variability in epidemiological studies of sleep using repeated nights of in-home polysomnography: SWAN sleep study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:87–96. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel W.M., Haas A., Ghosh-Dastidar B., Richardson A.S., Hale L., Buysse D.J., Buman M.P., Kurka J., Dubowitz T. Food Insecurity is Associated with Objectively Measured Sleep Problems. Behavioral Sleep Med. 2019:1–11. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2019.1669605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.El Zein A., Shelnutt K.P., Colby S., Vilaro M.J., Zhou W., Greene G., et al. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among U.S. college students: a multi-institutional study. BMC Publ Health. 2019;19:660. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6943-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Narcisse M.R., Long C.R., Felix H., Rowland B., Bursac Z., McElfish P.A., et al. The mediating role of sleep quality and quantity in the link between food insecurity and obesity across race and ethnicity. Obesity. 2018;26:1509–1518. doi: 10.1002/oby.22266. 19307381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Becerra M.B., Bol B.S., Granados R., Hassija C. Sleepless in school: the role of social determinants of sleep health among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2018;68:185–191. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1538148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.King C. Soft drinks consumption and child behaviour problems: the role of food insecurity and sleep patterns. Publ Health Nutr. 2017;20:266–273. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Covington L.B., Rogers V.E., Armstrong B., Storr C.L., Black M.M. Toddler bedtime routines and associations with nighttime sleep duration and maternal and household factors. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2019;15:865–871. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee E.S., Park S. Patterns of change in employment status and their association with self-rated health, perceived daily stress, and sleep among young adults in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kristiansen J., Persson R., Björk J., Albin M., Jakobsson K., Östergren P.O., et al. Work stress, worries, and pain interact synergistically with modelled traffic noise on cross-sectional associations with self-reported sleep problems. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84:211–224. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0557-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mai Q.D., Hill T.D., Vila-Henninger L., Grandner M.A. Employment insecurity and sleep disturbance: evidence from 31 European countries. J Sleep Res. 2019;28:8. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Khubchandani J., Price J. Association of job insecurity with health risk factors and poorer health in American workers. J Community Health. 2017;42:242–251. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mai Q.D., Jacobs A.W., Schieman S. Precarious sleep? Nonstandard work, gender, and sleep disturbance in 31 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2019;237:10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Maume D.J., Hewitt B., Ruppanner L. Gender equality and restless sleep among partnered Europeans. J Marriage Fam. 2018;80:1040–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Greubel J., Kecklund G. The impact of organizational changes on work stress, sleep, recovery and health. Ind Health. 2011;49:353–364. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Navarro-Carrillo G., Valor-Segura I., Moya M. The consequences of the perceived impact of the Spanish economic crisis on subjective well-being: the explanatory role of personal uncertainty. Curr Psychol. 2019;15 [Google Scholar]

- 108.Palmer K.T., D'Angelo S., Harris E.C., Linaker C., Sayer A.A., Gale C.R., et al. Sleep disturbance and the older worker: findings from the health and employment after fifty study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2017;43:136–145. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3618. Supplement. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Paine S., Gander P.H., Harris R., Reid P. Who reports insomnia? Relationships with age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic deprivation. Sleep. 2004;27:1163–1169. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Virtanen P., Vahtera J., Broms U., Sillanmäki L., Kivimäki M., Koskenvuo M. Employment trajectory as determinant of change in health-related lifestyle: the prospective HeSSup study. Eur J Publ Health. 2008;18:504–508. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]