Abstract

Background:

The locus coeruleus (LC), a brainstem nucleus comprising noradrenergic neurons, is one of the earliest regions affected by Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology in the cortex in AD is thought to exacerbate the age-related loss of LC neurons, which may lead to cortical tau pathology. However, mechanisms underlying LC neurodegeneration remain elusive.

Objective:

Here, we aimed to examine how noradrenergic neurons are affected by cortical Aβ pathology in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F knock-in mice.

Methods:

The density of noradrenergic axons in LC-innervated regions and the LC neuron number were analyzed by an immunohistochemical method. To explore the potential mechanisms for LC degeneration, we also examined the occurrence of tau pathology in LC neurons, the association of reactive gliosis with LC neurons, and impaired trophic support in the brains of AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice.

Results:

We observed a significant reduction in the density of noradrenergic axons from the LC in aged AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice without neuron loss or tau pathology, which was not limited to areas near Aβ plaques. However, none of the factors known to be related to the maintenance of LC neurons (i.e., somatostatin/somatostatin receptor 2, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, nerve growth factor, and neurotrophin-3) were significantly reduced in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates that cortical Aβ pathology induces noradrenergic neurodegeneration, and further elucidation of the underlying mechanisms will reveal effective therapeutics to halt AD progression.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β , locus coeruleus, neurotrophic factors, noradrenaline, somatostatin, tau

INTRODUCTION

The locus coeruleus (LC) is the major source of noradrenaline (NA) in the brain, and LC neurons innervate several brain regions that participate in a variety of brain functions, including cognition, sleep, emotion, and stress responses [1–4]. Malfunction in the LC–NA system is implicated in several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [3, 5–10]. Degeneration of LC noradrenergic neurons is one of the earliest and most prominent features of AD brains, with a loss of up to 70%of these neurons in some cases [11–17] and significant reductions in NA levels [14, 18–20]. The degeneration of LC neurons correlates with the severity of dementia [16, 21–23] and the progression of Braak stages in the brains of AD patients [24, 25]. Thus, neurodegeneration in the LC–NA system likely contributes to cognitive symptoms as well as agitation, aggression, and sleep disturbances that occur in preclinical and early-stage AD [26].

LC noradrenergic neurons have long, thin unmyelinated axons that project throughout the cortex [27–29], where they are vulnerable to toxic insults and to tau pathology during normal aging [30–32]. In AD, the amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques that accumulate in the cortex induce severe neuroinflammation [33, 34] that damages noradrenergic axons and may exacerbate tau pathology and neuronal death in the LC [3, 7, 9, 10]. Indeed, the neurons in the LC that project to the cortex show severe neuron loss and tau pathology, whereas the neurons in the caudal region of the LC that innervate the cerebellum and spinal cord are relatively spared [15, 35, 36].

To gain insight into the mechanisms by which Aβ pathology induces neurodegeneration in LC noradrenergic neurons, we evaluated the brains of wild-type (WT) (C57BL/6J) and App knock-in mice, a model of Aβ amyloidosis without amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) overexpression, at 24 months of age when these mice have sufficiently undergone the aging process. AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice harbor three familial AD (FAD) mutations (Swedish [NL], Arctic [G], and Beyreuther/Iberian [F]) and exhibit cognitive deficits and severe neuroinflammation accompanied by progressive Aβ pathology in the brain parenchyma, whereas AppNL/NL mice carrying only the Swedish mutation overproduce human Aβ but have no apparent Aβ pathology up to 24 months [37–41]. In this study, we found that AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice, but not AppNL/NL mice, undergo degeneration of noradrenergic afferents without prominent LC neuron loss, providing further evidence that formation of Aβ pathology in the brain parenchyma induces noradrenergic axonal degeneration. We also assessed the potential mechanisms underlying this event.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The App-KI (AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F and AppNL/NL) mice on a C57BL/6J genetic background [37] were obtained from RIKEN Center for Brain Science (Wako, Japan) and maintained at the Institute for Animal Experimentation in National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology as described previously [38, 39]. After weaning, all mice were housed socially in same-sex groups and only male mice were used for the experiments. The mice were kept in a controlled environment (constant temperature 22±1°C, humidity 50–60%, lights on 07:00–19:00), with food and water available ad libitum. All animal experimental procedures were performed according to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and other national regulations and policies with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee at National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Japan (Approval number: 2–45).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed in male mice of the three genotypes (n = 3–5/genotype) for free-floating sections. At 12 and 24 months of age, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of a combination of medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg), midazolam (4 mg/kg), and butorphanol (5 mg/kg) and then perfused intracardially with ice-cold saline followed by 4%paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), as previously described [39]. The whole brains were collected and immersed in the same fixative solution at 4°C overnight. For cryoprotection, the fixed brains were transferred into 20%and then 30%sucrose in 0.1 M PB at 4°C until the tissues sank. After frozen rapidly in cold isopentane, the brains were sliced coronally into 25μm sections using a cryostat (Leica CM3050; Leica Microsystems, Germany) and stored in a cryoprotectant solution (30%glycerol and 30%ethylene glycol in PBS) at –20°C until immunostaining. Two to six non-adjacent coronal sections (∼100μm apart) were selected at the level of prefrontal cortex (+2.10 to +1.70 mm from bregma), neocortex and hippocampus (–1.58 to –2.70 mm from bregma), entorhinal cortex (–4.24 to –4.60 mm from bregma), and LC (–5.34 to –5.68 mm from bregma) according to the mouse brain atlas [42]. After washing with PBS containing 0.1%Triton X-100 (PBS-T), the sections were blocked in a buffer containing 5%normal goat or donkey serum, 0.5%bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.3%Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 1) in a dilution buffer containing 3%normal goat or donkey serum, 0.5%BSA and 0.3%Triton X-100 in PBS. After three washes with PBS-T were given, the sections were then incubated for 2–3 h with appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies (Supplementary Table 1) in the dilution buffer. After three washes with PBS-T, the sections were incubated with DAPI (2μg/ml) for 5 min and mounted in Aqua-Poly/Mount (Polysciences Inc., USA). For Aβ staining, the sections stained with fluorescent secondary antibodies were incubated in 1-fluoro-2,5-bis (3-carboxy-4-hydroxystyryl) benzene (FSB) solution (10μg/ml in 50%EtOH) (F308; Dojindo, Japan) for 30 min and briefly washed with saturated lithium carbonate followed by 50%EtOH prior to mounting. Unstained sections and control sections without primary antibodies were processed to assess age-related autofluorescence and non-specific staining.

Image analysis and quantification

Immunofluorescence images of the sections were captured using either a LSM780 or LSM700 confocal laser-scanning microscope with a 10× or a 20× objective (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Laser and detector settings were maintained constant for each immunostaining. Image capturing and analyses was done independently by two experimenters blinded to mouse genotype in order to increase reproducibility. All image processing and analyses were performed with Fiji software.

Measurement of norepinephrine transporter (NET)-positive fiber length

For measuring length of NET-positive projecting fibers in cortical and hippocampal regions, we captured images using a LSM780 confocal microscopy with a 20× objective, and 10μm Z-stacks (0.85 μm interval between images) were reconstructed with a maximum intensity projection. For capturing the images from cortical regions, we set a capturing frame including layer II–IV using DAPI counterstaining as a guide in a consistent manner from section to section. The NET-positive fibers were segmented using an automated threshold algorithm (Otsu’s method) with adjustment of contrast and unsharp masking to sharpen and enhance the edge features. The resulting binary image was then skeletonized, and total skeleton length within the image was measured using Summarize Skeleton plugin. All images were processed with the same procedures. At least two Z-stack sets of images were reconstituted bilaterally per section and averaged over 4 sections in each mouse.

Counting of dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH)-positive cell in the LC

For counting number of DBH-positive neurons in the LC, we captured images using a LSM780 confocal microscopy with a 10× objective to capture the entire region of the LC, and 25μm Z-stacks (2.88μm interval between images) were reconstructed with a maximum intensity projection. For unbiased estimation of LC neuron number, the total number of DBH-positive cells was quantified using evenly spaced counting frames (50×50μm; 25μm frame interval) within each image. The average number of counting frames per mouse was 19.78±0.85. For each mouse, one or two Z-stack sets of images were reconstituted per section and averaged over 4–6 sections. We chose the coronal sections including the LC perikarya evenly through rostral to caudal portions (–5.34 to –5.68 mm from bregma).

Measurement of immunoreactivity for somatostatin receptor 2 (SSTR2) and somatostatin (SST) in the LC

For acquisition of SSTR2 immunofluorescence in the LC, we captured images using a LSM700 confocal microscopy with a 10× objective to capture the entire tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive area, and 25μm Z-stacks (3.45μm interval between images) was reconstituted with a maximum intensity projection. Two Z-stack sets of images were reconstituted per section and averaged over 2 sections in each mouse. For acquisition of SST immunofluorescence, we separately captured images using a LSM700 confocal microscopy with a 20× objective in one LC region (TH-positive) to clearly obtain punctate structures of SST immunofluorescence, and 15μm Z-stacks (0.96μm interval between images) were reconstructed with a maximum intensity projection. According to the size of TH-positive area in the stacked image, two to four Z-stack sets of images were reconstituted per section and averaged over two sections. A region of interest (ROI) was manually drawn for showing the LC region using TH counterstaining as a guide. After background subtraction, immunoreactivity for SSTR2 and SST in the LC was defined as numbers of signal-positive pixels within a defined ROI (# of positive pixels/mm2), which were determined from binarized images of immunofluorescence by thresholding with an automated threshold method (Otsu’s method). Pixels with sufficient fluorescence were assigned with a value of 1 and other pixels with subthreshold intensity were assigned with a value of 0. The same procedures were applied across all other images, and all binarized images were visually inspected to ensure adequate detection. The immunoreactivity for each signal (# of positive pixels/mm2) was expressed as a relative ratio to WT mice.

Measurement of cortical immunoreactivity for neurotrophic factors in the neocortex

For acquisition of immunofluorescence for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), and neurotophin-3 (NT-3) in the neocortex, we captured images using a LSM700 confocal microscopy with a 20× objective, and 10μm Z-stacks (0.96μm interval between images) were reconstructed with a maximum intensity projection. For capturing the images from the neocortex, we set a capturing frame including layer II–IV using DAPI counterstaining as a guide in a consistent manner. Age-related autofluorescence was imaged in the blank red (594 wavelength) channel and reduced by subtraction from the green (488 wavelength) channel image. Immunoreactivity for BDNF, NGF, and NT-3 in the neocortex was defined as numbers of signal-positive pixels within an entire image (# of positive pixels/mm2), which were determined from binarized images of immunofluorescence by thresholding with an automated threshold method (Otsu’s method for BDNF and IsoData method for NGF and NT-3). Pixels with sufficient fluorescence were assigned with a value of 1 and other pixels with subthreshold intensity were assigned with a value of 0. The same procedures were applied across all other images, and all binarized images were visually inspected to ensure adequate detection. The immunoreactivity for each signal (# of positive pixels/mm2) was expressed as a relative ratio to WT mice. Four Z-stack sets of images were reconstituted per section and averaged over two sections in each mouse.

RNA extraction and quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

For qRT-PCR analysis, frontal cortex from male mice of the 3 genotypes (n = 5–6/genotype) at 24 months of age were used. The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of a combination of medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg), midazolam (4 mg/kg), and butorphanol (5 mg/kg), and perfused intracardially with ice-cold saline. Frontal cortex regions of brains were dissected and were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and reverse-transcribed using PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa Bio, Japan). qRT-PCR was performed using Thunderbird SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Japan) on a CFX96 real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA). Expression of genes of interest was standardized relative to Actb (β-actin). Relative expression values were determined by the ΔΔCT method. Primer sequences used in this study were listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Statistical analysis

As described previously [38, 39], one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s post hoc tests was used for the comparisons of multiple means with genotypes as one independent variable. All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP software (version 11, SAS Institute Inc., USA). Data are presented as mean±SEM. All alpha levels were set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Widespread loss of noradrenergic axons in cortical and hippocampal regions in aged AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice

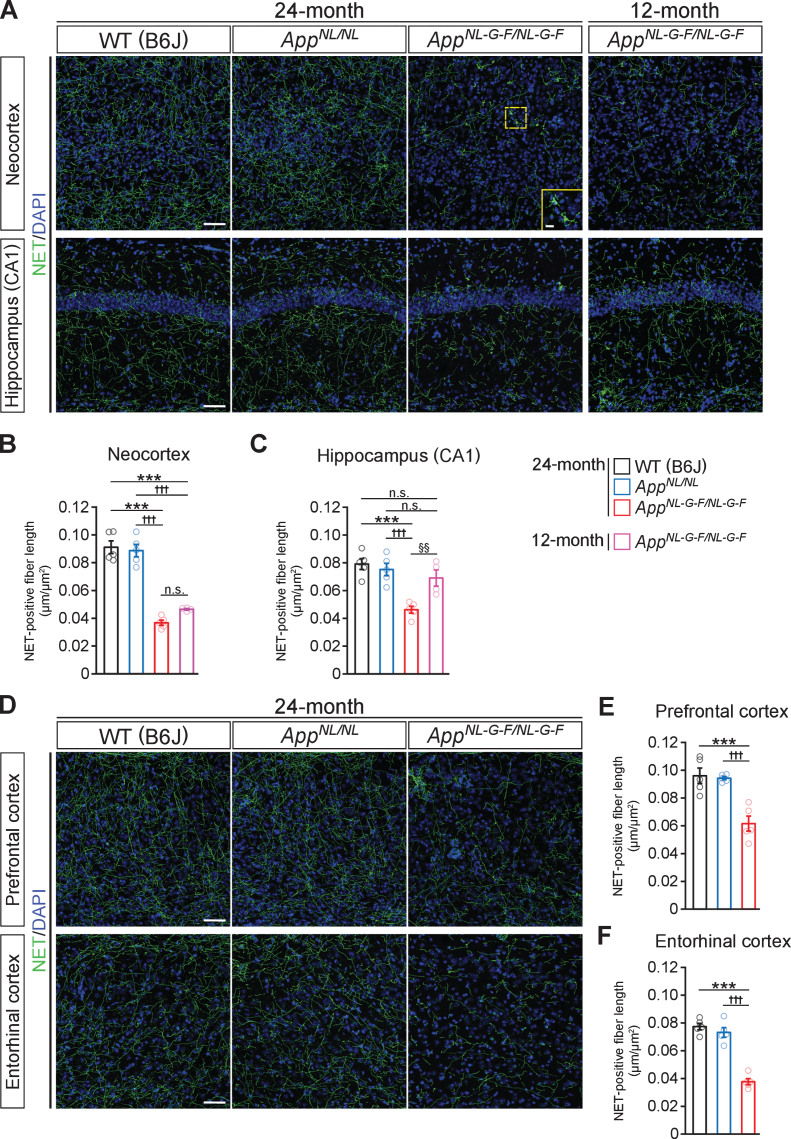

To determine how Aβ amyloidosis affects the noradrenergic system, we utilized AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice, which develop massive Aβ plaques and reactive gliosis in the brain parenchyma. We stained brain sections from 24-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F, AppNL/NL and WT control mice with an antibody against norepinephrine transporter (NET), a marker of noradrenergic axon terminals. In the neocortex and CA1 subfield of the hippocampus in 24-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice, the density of NET-positive fibers was significantly reduced compared with that in WT mice (Fig. 1A), and the remaining noradrenergic axons showed structural abnormalities consistent with axonal dystrophy (Fig. 1A, insets). Specifically, compared to AppNL/NL and WT mice, there was a significant decrease in the density of NET-positive fibers in both brain regions (Fig. 1B, C). By contrast, compared to WT control, the density of NET-positive fibers was not altered in AppNL/NL mice (Fig. 1A–C), which do not develop Aβ pathology despite elevated production of Aβ and other β-site cleavage products of AβPP. To ask whether noradrenergic afferents start to degenerate at an earlier time point, we analyzed the NET-positive fiber density in 12-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice (Fig. 1A). We found that the density of NET-positive fibers in the neocortex was similar between 12-month-old and 24-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice (Fig. 1B), while that in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus was more preserved in 12-month-old than 24-month-old, and was equivalent to 24-month-old AppNL/NL and WT mice (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that Aβ pathology induces widespread loss of noradrenergic afferents in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice.

Fig. 1.

Loss of noradrenergic afferents is observed in cortical and hippocampal regions in 12- and 24-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. A) Representative images of the neocortex and hippocampal CA1 subfield from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-NET (indicated by green) were shown (blue indicated DAPI staining). B, C) Total length of NET-positive fiber was measured and expressed as fiber length per area (μm/μm2) in the neocortex (B) and hippocampal CA1 subfield (C). D) Representative images of the prefrontal and entorhinal cortices from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-NET (indicated by green) were shown (blue indicated DAPI staining). E, F) Total length of NET-positive fiber was measured and expressed as fiber length per area (μm/μm2) in the prefrontal cortex (E) and entorhinal cortex (F). Scale bars represent 50μm. In the inset image, scale bar represents 10μm. n = 4–5/group. ***p < 0.001 versus WT (B6J); †††p<0.001 versus AppNL/NL; §§p < 0.01 versus 12-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F. n.s., not significant.

Since LC noradrenergic neurons send extensive projections throughout the brain, we further examined the density of NET-positive fibers in other LC-innervated regions known to be affected in AD (Fig. 1D). The reduced NET-positive fiber density was also observed in the prefrontal cortex (Fig. 1E) and entorhinal cortex (Fig. 1F) in 24-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice compared with AppNL/NL and WT mice.

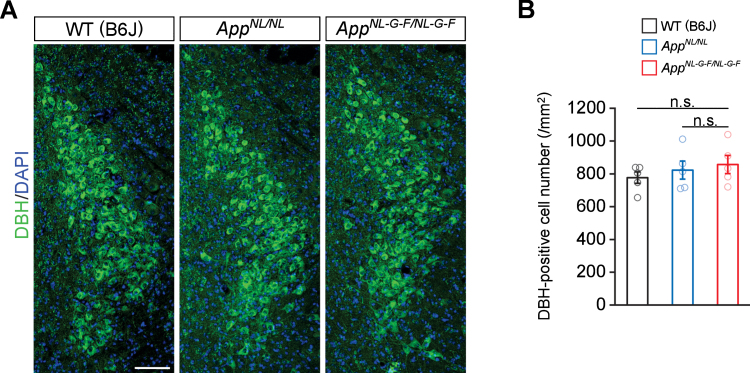

Prominent neuron loss is not observed in the LC in aged AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice

To determine if the reduction in noradrenergic afferents in the cortex and hippocampus reflects neuron loss in the LC, we immunostained brain sections containing the LC perikarya from WT, AppNL/NL, and AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice by using an antibody against dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), a marker for noradrenergic neurons (Fig. 2A). Quantitative analysis revealed similar numbers of DBH-positive cells in the LC regions among all genotypes (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that the loss of noradrenergic afferents in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice occurs in the absence of LC neuron loss.

Fig. 2.

No prominent neuron loss is detected in the LC in 24-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. A) Representative images of the LC from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-DBH (indicated by green) were shown (blue indicated DAPI staining). B) Number of DBH-positive cells was measured and expressed as cell number per area (/mm2). Scale bar represents 100μm. n = 5/genotype. n.s., not significant.

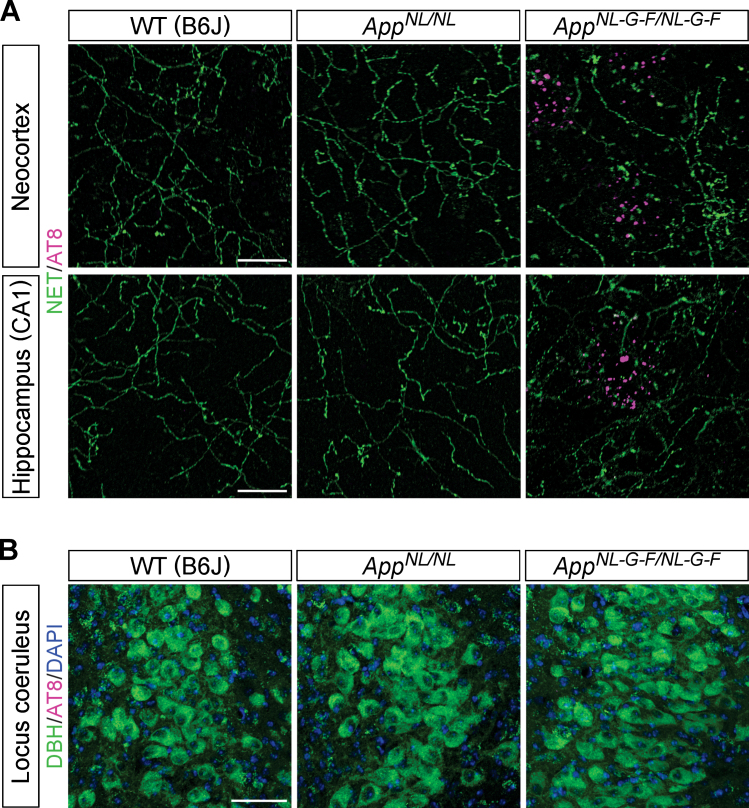

Phospho-tau pathology is not associated with the LC–NA system in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice

Since one of the first signs of AD-related pathology in human brains is the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau in LC noradrenergic neurons, we examined whether the dystrophic NET-positive fibers that we observed in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mouse brains (Fig. 1A, inset) were associated with an accumulation of AD-related phospho-tau. An antibody which recognizes tau phosphorylated at AD-related Ser202 and Thr205 (AT8 antibody) detects punctate structures surrounding Aβ plaques in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice [43], and these AT8-positive phospho-tau signals did not colocalize with the dystrophic NET-positive fibers in the neocortex or hippocampus in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice (Fig. 3A). Also, no phosphorylated tau was detected within the cell bodies of noradrenergic neurons in the LC (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that loss of noradrenergic afferents and axonal degeneration occur in the absence of prominent tau pathology in LC noradrenergic neurons in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice.

Fig. 3.

Phospho-tau pathology is not associated with the LC-NA system. A) Representative images of the neocortex and hippocampal CA1 subfield from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-phospho tau (AT8) (indicated by magenta) and anti-NET (indicated by green) antibodies were shown. Scale bars represent 20μm. B) Representative images of the LC from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-phospho tau (AT8) (indicated by magenta) and anti-DBH (indicated by green) antibodies were shown (blue indicated DAPI staining). Scale bar represents 50μm. n = 3/genotype.

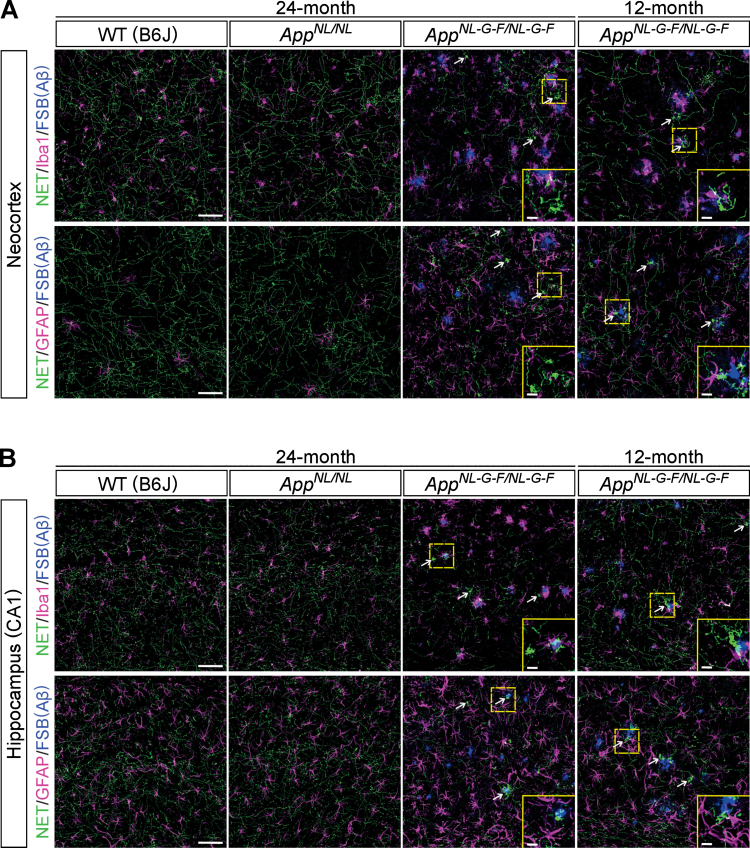

Loss of noradrenergic afferents is not limited to areas with Aβ plaques or reactive gliosis in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice

Neuroinflammation is a common feature of brains of AD patients. As AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice develop massive reactive gliosis (microgliosis and astrocytosis) around Aβ plaques, we examined whether the observed loss of noradrenergic axons and the aberrant clusters occurred in proximity to Aβ plaques and regions of reactive gliosis. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that regions with a low density of NET-positive fibers were not limited to areas near Aβ plaques or ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1)-positive microglia or glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytes in the neocortex (Fig. 4A) or hippocampus (Fig. 4B) of 24-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. We also performed the same analysis in 12-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice and found that regions with reduced NET-positive fibers were not limited to areas near Aβ plaques or activated glial cells in the neocortex (Fig. 4A) and hippocampus (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, however, we noticed that areas with aberrant NET-positive fiber clusters were often associated with Aβ plaques surrounded by Iba1-positive microglia in the neocortex (Fig. 4A, white arrows, high-magnification views in insets) and hippocampus (Fig. 4B, white arrows, high-magnification views in insets), which is more evident in 12-month-old AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. These data suggest a potential role of neuroinflammation in the formation of aberrant NET-positive fiber clusters in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice brains.

Fig. 4.

Noradrenergic axonal degeneration is not limited to the vicinity of Aβ plaques and reactive gliosis. A, B) Representative images of the neocortex (A) and hippocampal CA1 subfield (B) from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-NET (indicated by green in A and B), anti-Iba1 (indicated by magenta in upper panels of A and B) and anti-GFAP (indicated by magenta in lower panels of A and B) antibodies were shown. FSB was used for detecting Aβ plaques (indicated by blue in A and B). White arrows point to representative examples of aberrant NET-positive fiber cluster. Insets show higher-magnification views in the corresponding dashed yellow squares. Scale bars represent 50μm. In the inset images, scale bars represent 10μm. n = 3/group.

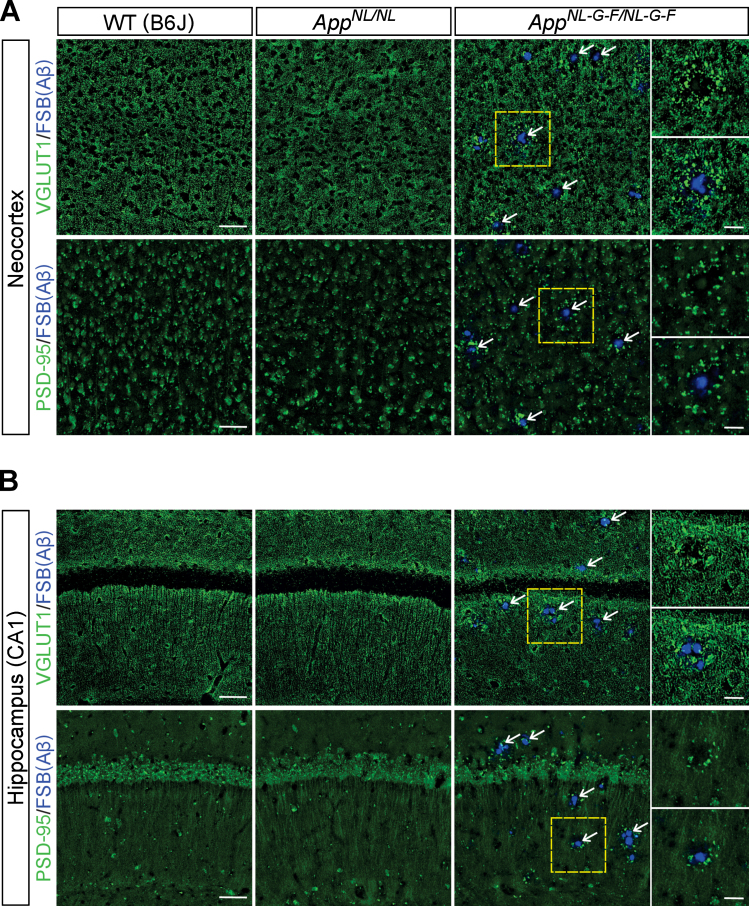

Loss of glutamatergic synapses near Aβ plaques in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice

Since cortical regions in AD brains exhibit reductions in vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1)-positive glutamatergic terminals [44], we examined the spatial relationship between the loss of glutamatergic terminals and Aβ plaques in cortical and hippocampal regions in our aged AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that immunoreactivity for VGLUT1-positive punctate structures was lost at the site of Aβ plaques, while larger aberrant (bulbous-like) shapes positive for VGLUT1, an evidence of dystrophic neurites, appeared around Aβ plaques in the neocortex (Fig. 5A, white arrows, higher-magnification images in the inset) and hippocampus (Fig. 5B, white arrows, higher-magnification images in the inset). In contrast, VGLUT1-positive glutamatergic terminals were spared in the areas distant from Aβ plaques in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice (Fig. 5A, B), which were different from the widespread reduction of NET-positive fibers (Fig. 4). Immunostaining with an antibody against postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) similarly revealed reduced immunoreactivity at the site of Aβ plaques with large aberrant structures surrounding plaques in the neocortex (Fig. 5A, white arrows, higher-magnification images in the inset) and hippocampus (Fig. 5B, white arrows, higher-magnification images in the inset). These results indicate that, unlike noradrenergic afferents, glutamatergic terminals and synapses were lost in the vicinity of Aβ plaques in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice.

Fig. 5.

Loss of glutamatergic synapses is associated with the vicinity of Aβ plaques. A, B) Representative images of the neocortex (A) and hippocampal CA1 subfield (B) from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-VGLUT1 and anti-PSD-95 antibodies (indicated by green in A and B) were shown. FSB was used for detecting Aβ plaques (indicated by blue in A and B). White arrows point to representative examples of Aβ plaque. Insets show higher-magnification views in the corresponding dashed yellow squares. Scale bars represent 50μm. In the inset images, scale bars represent 20μm. n = 3/genotype.

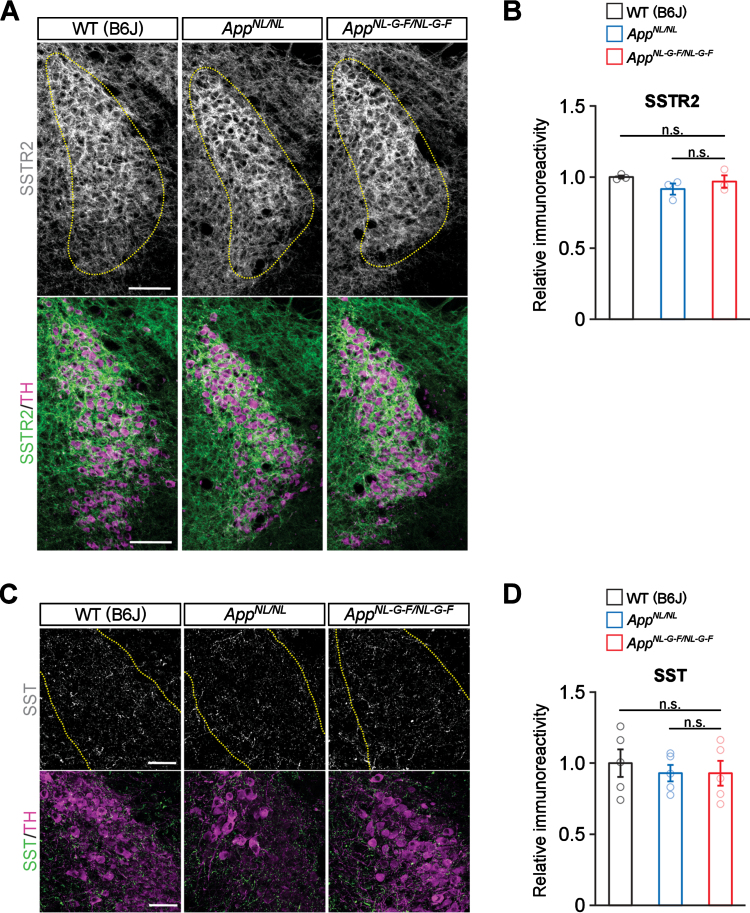

No prominent reduction of somatostatin or somatostatin receptor 2 in the LC in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice

Somatostatin (SST) is known to control activity and growth of noradrenergic neurons through activation of somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) including SSTR2a, which is highly expressed in LC neurons. Levels of SSTR2a in the LC [45] as well as of SST in the cortex [46] are decreased in AD, and interestingly, LC noradrenergic axons degenerate in cortices of Sstr2 knockout mice [45]. Thus, impaired SST/SSTR signaling may cause an excitatory imbalance and/or disrupt trophic support in the LC, leading to subsequent axonal degeneration in AD. To test this possibility, we performed immunohistochemical analyses of LC neurons in aged mice with antibodies against SSTR2 and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a marker for noradrenergic neurons in the LC (Fig. 6A). We detected similar levels of SSTR2 expression in LC neurons of AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F, AppNL/NL, and WT mice (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, immunostaining for SST revealed no differences between the mouse groups in the LC areas containing SST-positive varicosities (Fig. 6C, D). These results suggest that somatostatinergic signaling in the LC is not dramatically altered in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice.

Fig. 6.

No prominent reduction of somatostatin and somatostatin receptor 2 are detected in the LC. A) Representative images of the LC from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-SSTR2 (indicated by gray for single color images or green for multicolor images) and anti-TH (indicated by magenta for multicolor images) antibodies were shown. Scale bar represents 100μm. B) SSTR2 immunoreactivity in the TH-positive LC region (indicated by yellow dotted lines) was evaluated and expressed as a relative ratio to WT (B6J). C) Representative images of the LC from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-SST (indicated by gray for single color images or green for multicolor images) and anti-TH (indicated by magenta for multicolor images) antibodies were shown. Scale bar represents 50μm. D) SST immunoreactivity in the TH-positive LC region (indicated by yellow dotted lines) was evaluated and expressed as a relative ratio to WT (B6J). n = 3–5/genotype. n.s., not significant.

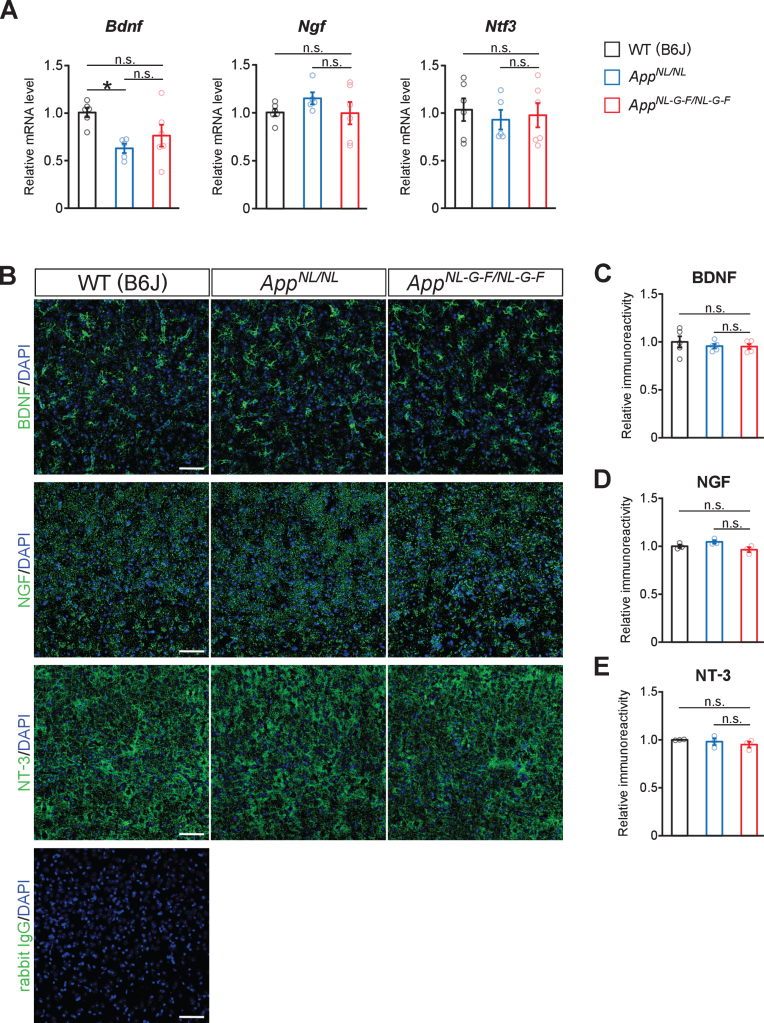

No prominent reduction in neurotrophic factors implicated in the development and/or maintenance of noradrenergic neurons in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice

The neurotrophic factors, including BDNF, NGF, NT-3, and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), are crucial for the development, survival, and maintenance of noradrenergic neurons [5]. We thus examined whether the expression of BDNF and other trophic factors is altered in the neocortices of AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis revealed that mRNA levels of Bdnf, Ngf and Ntf3 were not altered in the cortex of AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice compared with WT or AppNL/NL mice, while Bdnf mRNA level was significantly lower in AppNL/NL mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 7A). In contrast, the mRNA expression level of Gdnf was too low to detect by our qRT-PCR analysis. We next performed immunohistochemical analyses and found that the expression pattern of BDNF was similar between AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F, AppNL/NL, and WT mouse brains (Fig. 7B), with no significant difference in the BDNF immunoreactivity (Fig. 7C). Similar expression patterns among the mouse groups were also observed for NGF (Fig. 7D) and NT-3 (Fig. 7E). Immunostaining without primary antibodies under the same settings of image capturing did not show any signals from brain sections, suggesting that observed signals represent expression of these neurotrophic factors (Fig. 7B). Taken together, these results suggest that the expression of trophic factors implicated in the maintenance of the LC is not significantly altered in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice.

Fig. 7.

No prominent reduction in neurotrophic factors for noradrenergic neurons are detected in the neocortex. A) mRNA levels of Bdnf, Ngf, and Ntf3 in the cortex were analyzed by qRT-PCR. n = 5–6/genotype. *p < 0.05 versus WT (B6J). B) Representative images of the neocortex from frozen coronal brain sections immunostained with anti-BDNF, anti-NGF, and anti-NT-3 antibodies (all indicated by green) were shown. Sections stained with secondary anti-rabbit IgG antibody (indicated by green) was served as a negative control (blue indicated DAPI staining). C–E) Immunoreactivity of BDNF (C), NGF (D), and NT-3 (E) were evaluated and expressed as a relative ratio to WT (B6J). Scale bars represents 50μm. n = 3–5/genotype. n.s., not significant.

DISCUSSION

Neuron loss in the LC in AD was hypothesized to result from retrograde degeneration of the cortical projections [29, 47]. LC neurons projecting to cortical regions are selectively affected in AD, whereas neurons without cortical projections show no pathology [35, 36, 48]. Accordingly, the reductions in noradrenergic afferents and NA content in forebrain LC target regions observed in early-stage AD [6, 10, 20] are followed by neuron loss in the LC at mid-to-advanced Braak stages [9, 30, 49]. Our findings are consistent with these reports, as AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice had significantly reduced densities of noradrenergic axons in the cortex without neuron loss in the LC (Figs. 1 and 2).

The degeneration of LC neurons in human brains has been associated with the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau [50–52]. In the pathogenesis of AD, the accumulation of Aβ pathology in cortical areas is thought to drive tau pathology and neuron loss in the LC; however, the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. A recent study demonstrated that aberrant TH-positive noradrenergic and dopaminergic terminals were negative for phospho-tau in the cortices of AD brains [45]. Consistent with this, we found no tau pathology in areas with noradrenergic axonal degeneration in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice (Fig. 3). These results suggest that axonal degeneration of LC neuron is initiated by Aβ pathology, which may exacerbate tau pathology independently formed in the LC and further damage LC neurons in AD pathogenesis.

Several studies have reported degeneration of the LC–NA system in transgenic mouse models. In APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice overexpressing FAD-related mutant APPswe and PS1ΔE9, progressive Aβ pathology in the forebrain correlates with the progressive loss of TH-positive catecholaminergic axons, followed by atrophy of cell bodies and loss of TH-positive neurons in the LC in the absence of prominent tau pathology [53–55]. Aβ pathology in these mice is modestly reduced by the administration of anti-Aβ antibodies, which also ameliorates the loss of TH-positive catecholaminergic axons, suggesting a causal link between Aβ pathology and catecholaminergic axonal degeneration [56]. In Tg2576 mice overexpressing FAD-related APPswe, the volume of the LC and the number of DBH-positive neurons are reduced as Aβ pathology progresses [57], while PDAPP mice overexpressing FAD-related APPV717F exhibit selective shrinkage only in the portion of the LC that projects to the cortex and hippocampus [58]. By contrast, neuronal hypertrophy in the LC was observed in immunohistochemical analyses of 6-month-old 5×FAD mice, which overexpress AβPP with the Swedish (K670N, M671L), Florida (I716V), and London (V717I) FAD mutations along with human presenilin 1 (PS1) harboring two FAD mutations, M146L and L286V [59]. In contrast, APP23 mice overexpressing FAD-related APPswe exhibited no prominent loss of TH-positive LC neurons at 12 months of age [60]. Interestingly, a very recent study using AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice showed that a loss of TH-positive LC neurons at 9-month-old [61]; however, we did not detect a loss of DBH-positive neurons in these mice up to 24 months of age (Fig. 2). The reason for the inconsistent results between the studies may be related to the differences in calculation method for the number of LC neurons, experimental design for immunohistochemistry and laboratory-specific environmental conditions. Supporting this, Mehla et al. reported significant decline in spatial learning and memory in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice at 6 months of age [61], while we and others did not detect prominent learning and memory deficits at the same age [38, 62, 63]. Despite the differences in degenerative phenotypes between mouse models and research groups, none of the models develop overt tau pathology in the LC, further supporting the notion that damage to LC neurons induced by Aβ pathology is independent of tau accumulation.

Axonopathy has been reported in different transgenic mouse models of Aβ amyloidosis, which often overexpress human AβPP [64–68]. However, several studies have demonstrated that unphysiologically overexpressed AβPP proteins impair axonal transport by interacting with kinesin [69] through c-Jun amino-terminal kinase interacting proteins [70] and cause axonopathy [69, 71, 72]. These reports suggest that axonopathy observed in AβPP transgenic mice might be, at least in part, due to unphysiologically overexpressed AβPP proteins. In contrast, this study utilized AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice, which express physiological levels of AβPP under the innate promoter [37, 41], and demonstrated that Aβ pathology was required to induce noradrenergic axonal degeneration in mice brains. These results provide further evidence that AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice are useful models to investigate critical neurodegenerative processes at an early stage of AD.

It is not clear how Aβ pathology induces neurodegeneration of LC neurons in AD. Chronic neuroinflammation is induced by Aβ pathology and activated microglia and reactive astrocytes have been suggested to promote neurodegeneration by engulfing neuronal or synaptic structures in AD [73–75]. Our histochemical analyses did not detect clear evidence that reactive gliosis played causative roles in reductions of NET-positive fibers. However, dystrophic noradrenergic fiber clusters were often associated with Aβ plaques surrounded by activated microglia (Fig. 4), suggesting a potential involvement of neuroinflammation in noradrenergic axonal degeneration in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines via microglial activation in the brain of APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice were accompanied by the loss of LC–NA neuronal somas and axon terminals [76]. Since AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice also display massive microgliosis and elevated cytokine response in the cortex [77, 78], further investigation is required to delineate a role of neuroinflammation in noradrenergic neurodegeneration caused by Aβ pathology.

Several brain regions send SST-positive projections to the LC [79–81], and reduced SST signaling in AD brains [46, 82] may disrupt inhibitory regulation of [83–85] and/or trophic effects on [86–88] noradrenergic neurons. Supporting this possibility, Sstr2 knock out results in the degeneration of LC noradrenergic axons in mouse cortex [45]. In addition, LC neuron development and survival depend on a variety of trophic factors [89–94] that can be retrogradely transported from target regions [95]. For example, BDNF is involved in several aspects of LC neuronal development and maturation [96–98], and a reduced level of BDNF promotes the degeneration of LC axons in 5×FAD mice [99]. However, neither SST innervation/SSTR2 levels in the LC (Fig. 6) nor cortical expression of trophic factors, including BDNF, NGF, and NT-3 (Fig. 7), were altered in AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. These data suggest that cortical Aβ pathology induces noradrenergic axonal degeneration through an as-yet-unknown factor(s). Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanism(s), which will reveal how Aβ pathology initiates AD pathogenesis.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that cortical Aβ pathology in LC target regions induces noradrenergic axonal degeneration. AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice used in this study harbor three FAD mutations to produce massive Aβ pathology in the brain parenchyma [37, 41], which is thought to play a central role in the pathogenesis of not only familial but also sporadic cases of AD. Given the critical roles of LC neurons in cognitive and physiological processes, as well as in AD pathogenesis, approaches to prevent axonal damage of LC noradrenergic neurons may be an effective way to prevent the onset and slow the progression of AD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. JP18K15381, the Uehara Memorial Foundation (JP) (to Y.S.), JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. JP20H03571, the Research Funding for Longevity Science from National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Japan, Grant No. 19-7 and 21-13, DAIKO FOUNDATION (JP) (to K.M.I.), and the Research Funding for Longevity Science from National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Japan, Grant No. 19-49 (to M.S.).

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/21-0385r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210385.

REFERENCES

- [1].Poe GR, Foote S, Eschenko O, Johansen JP, Bouret S, Aston-Jones G, Harley CW, Manahan-Vaughan D, Weinshenker D, Valentino R, Berridge C, Chandler DJ, Waterhouse B, Sara SJ (2020) Locus coeruleus: A new look at the blue spot. Nat Rev Neurosci 21, 644–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sara SJ (2009) The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 10, 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Satoh A, Iijima KM (2019) Roles of tau pathology in the locus coeruleus (LC) in age-associated pathophysiology and Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: Potential strategies to protect the LC against aging. Brain Res 1702, 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schwarz LA, Luo L (2015) Organization of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system. Curr Biol 25, R1051–R1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Feinstein DL, Kalinin S, Braun D (2016) Causes, consequences, and cures for neuroinflammation mediated via the locus coeruleus: Noradrenergic signaling system. J Neurochem 139(Suppl 2), 154–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gannon M, Che P, Chen Y, Jiao K, Roberson ED, Wang Q (2015) Noradrenergic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci 9, 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Matchett BJ, Grinberg LT, Theofilas P, Murray ME (2021) The mechanistic link between selective vulnerability of the locus coeruleus and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 141, 631–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ross JA, McGonigle P, Van Bockstaele EJ (2015) Locus coeruleus, norepinephrine and Abeta peptides in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Stress 2, 73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Simic G, Babic Leko M, Wray S, Harrington CR, Delalle I, Jovanov-Milosevic N, Bazadona D, Buee L, de Silva R, Di Giovanni G, Wischik CM, Hof PR (2017) Monoaminergic neuropathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neurobiol 151, 101–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weinshenker D (2018) Long road to ruin: Noradrenergic dysfunction in neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci 41, 211–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bondareff W, Mountjoy CQ, Roth M (1982) Loss of neurons of origin of the adrenergic projection to cerebral cortex (nucleus locus ceruleus) in senile dementia. Neurology 32, 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chan-Palay V, Asan E (1989) Alterations in catecholamine neurons of the locus coeruleus in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type and in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia and depression. J Comp Neurol 287, 373–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iversen LL, Rossor MN, Reynolds GP, Hills R, Roth M, Mountjoy CQ, Foote SL, Morrison JH, Bloom FE (1983) Loss of pigmented dopamine-beta-hydroxylase positive cells from locus coeruleus in senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type. Neurosci Lett 39, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mann DM, Lincoln J, Yates PO, Stamp JE, Toper S (1980) Changes in the monoamine containing neurones of the human CNS in senile dementia. Br J Psychiatry 136, 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tomlinson BE, Irving D, Blessed G (1981) Cell loss in the locus coeruleus in senile dementia of Alzheimer type. J Neurol Sci 49, 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zarow C, Lyness SA, Mortimer JA, Chui HC (2003) Neuronal loss is greater in the locus coeruleus than nucleus basalis and substantia nigra in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Arch Neurol 60, 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zweig RM, Ross CA, Hedreen JC, Steele C, Cardillo JE, Whitehouse PJ, Folstein MF, Price DL (1989) Neuropathology of aminergic nuclei in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Clin Biol Res 317, 353–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Adolfsson R, Gottfries CG, Roos BE, Winblad B (1979) Changes in the brain catecholamines in patients with dementia of Alzheimer type. Br J Psychiatry 135, 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Matthews KL, Chen CP, Esiri MM, Keene J, Minger SL, Francis PT (2002) Noradrenergic changes, aggressive behavior, and cognition in patients with dementia. Biol Psychiatry 51, 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Palmer AM, Wilcock GK, Esiri MM, Francis PT, Bowen DM (1987) Monoaminergic innervation of the frontal and temporal lobes in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res 401, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bondareff W, Mountjoy CQ, Roth M, Rossor MN, Iversen LL, Reynolds GP, Hauser DL (1987) Neuronal degeneration in locus ceruleus and cortical correlates of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1, 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kelly SC, He B, Perez SE, Ginsberg SD, Mufson EJ, Counts SE (2017) Locus coeruleus cellular and molecular pathology during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 5, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wilson RS, Nag S, Boyle PA, Hizel LP, Yu L, Buchman AS, Schneider JA, Bennett DA (2013) Neural reserve, neuronal density in the locus ceruleus, and cognitive decline. Neurology 80, 1202–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Andres-Benito P, Fernandez-Duenas V, Carmona M, Escobar LA, Torrejon-Escribano B, Aso E, Ciruela F, Ferrer I (2017) Locus coeruleus at asymptomatic early and middle Braak stages of neurofibrillary tangle pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 43, 373–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Theofilas P, Ehrenberg AJ, Dunlop S, Di Lorenzo Alho AT, Nguy A, Leite REP, Rodriguez RD, Mejia MB, Suemoto CK, Ferretti-Rebustini REL, Polichiso L, Nascimento CF, Seeley WW, Nitrini R, Pasqualucci CA, Jacob Filho W, Rueb U, Neuhaus J, Heinsen H, Grinberg LT (2017) Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer’s disease progression: A stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discovery. Alzheimers Dement 13, 236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stern AL, Naidoo N (2015) Wake-active neurons across aging and neurodegeneration: A potential role for sleep disturbances in promoting disease. Springerplus 4, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Foote SL, Bloom FE, Aston-Jones G (1983) Nucleus locus ceruleus: New evidence of anatomical and physiological specificity. Physiol Rev 63, 844–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nagai T, Satoh K, Imamoto K, Maeda T (1981) Divergent projections of catecholamine neurons of the locus coeruleus as revealed by fluorescent retrograde double labeling technique. Neurosci Lett 23, 117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].German DC, White CL, 3rd, Sparkman DR (1987) Alzheimer’s disease: Neurofibrillary tangles in nuclei that project to the cerebral cortex. Neuroscience 21, 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mather M, Harley CW (2016) The locus coeruleus: Essential for maintaining cognitive function and the aging brain. Trends Cogn Sci 20, 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mravec B, Lejavova K, Cubinkova V (2014) Locus (coeruleus) minoris resistentiae in pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 11, 992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pamphlett R (2014) Uptake of environmental toxicants by the locus ceruleus: A potential trigger for neurodegenerative, demyelinating and psychiatric disorders. Med Hypotheses 82, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, de Strooper B, Frisoni GB, Salloway S, Van der Flier WM (2016) Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 388, 505–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT (2011) Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 1, a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].German DC, Manaye KF, White CL, 3rd, Woodward DJ, McIntire DD, Smith WK, Kalaria RN, Mann DM (1992) Disease-specific patterns of locus coeruleus cell loss. Ann Neurol 32, 667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Marcyniuk B, Mann DM, Yates PO (1986) Loss of nerve cells from locus coeruleus in Alzheimer’s disease is topographically arranged. Neurosci Lett 64, 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Saito T, Matsuba Y, Mihira N, Takano J, Nilsson P, Itohara S, Iwata N, Saido TC (2014) Single App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 17, 661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sakakibara Y, Sekiya M, Saito T, Saido TC, Iijima KM (2018) Cognitive and emotional alterations in App knock-in mouse models of Abeta amyloidosis. BMC Neurosci 19, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sakakibara Y, Sekiya M, Saito T, Saido TC, Iijima KM (2019) Amyloid-beta plaque formation and reactive gliosis are required for induction of cognitive deficits in App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurosci 20, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Salas IH, Callaerts-Vegh Z, D’Hooge R, Saido TC, Dotti CG, De Strooper B (2018) Increased insoluble amyloid-beta induces negligible cognitive deficits in old AppNL/NL knock-in mice. J Alzheimers Dis 66, 801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sasaguri H, Nilsson P, Hashimoto S, Nagata K, Saito T, De Strooper B, Hardy J, Vassar R, Winblad B, Saido TC (2017) APP mouse models for Alzheimer’s disease preclinical studies. EMBO J 36, 2473–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ (2001) The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates, Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Saito T, Mihira N, Matsuba Y, Sasaguri H, Hashimoto S, Narasimhan S, Zhang B, Murayama S, Higuchi M, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, Saido TC (2019) Humanization of the entire murine Mapt gene provides a murine model of pathological human tau propagation. J Biol Chem 294, 12754–12765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kirvell SL, Esiri M, Francis PT (2006) Down-regulation of vesicular glutamate transporters precedes cell loss and pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 98, 939–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Adori C, Gluck L, Barde S, Yoshitake T, Kovacs GG, Mulder J, Magloczky Z, Havas L, Bolcskei K, Mitsios N, Uhlen M, Szolcsanyi J, Kehr J, Ronnback A, Schwartz T, Rehfeld JF, Harkany T, Palkovits M, Schulz S, Hokfelt T (2015) Critical role of somatostatin receptor 2 in the vulnerability of the central noradrenergic system: New aspects on Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 129, 541–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gahete MD, Rubio A, Duran-Prado M, Avila J, Luque RM, Castano JP (2010) Expression of Somatostatin, cortistatin, and their receptors, as well as dopamine receptors, but not of neprilysin, are reduced in the temporal lobe of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis 20, 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Saper CB, Wainer BH, German DC (1987) Axonal and transneuronal transport in the transmission of neurological disease: Potential role in system degenerations, including Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 23, 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Parvizi J, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio A (2001) The selective vulnerability of brainstem nuclei to Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 49, 53–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Theofilas P, Dunlop S, Heinsen H, Grinberg LT (2015) Turning on the light within: Subcortical nuclei of the isodentritic core and their role in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Alzheimers Dis 46, 17–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Braak H, Del Tredici K (2011) The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol 121, 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K (2011) Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: Age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 70, 960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Grudzien A, Shaw P, Weintraub S, Bigio E, Mash DC, Mesulam MM (2007) Locus coeruleus neurofibrillary degeneration in aging, mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 28, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liu L, Luo S, Zeng L, Wang W, Yuan L, Jian X (2013) Degenerative alterations in noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res 8, 2249–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Liu Y, Yoo MJ, Savonenko A, Stirling W, Price DL, Borchelt DR, Mamounas L, Lyons WE, Blue ME, Lee MK (2008) Amyloid pathology is associated with progressive monoaminergic neurodegeneration in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 28, 13805–13814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].O’Neil JN, Mouton PR, Tizabi Y, Ottinger MA, Lei DL, Ingram DK, Manaye KF (2007) Catecholaminergic neuronal loss in locus coeruleus of aged female dtg APP/PS1 mice. J Chem Neuroanat 34, 102–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Liu Y, Lee MK, James MM, Price DL, Borchelt DR, Troncoso JC, Oh ES (2011) Passive (amyloid-beta) immunotherapy attenuates monoaminergic axonal degeneration in the AbetaPPswe/PS1dE9 mice. J Alzheimers Dis 23, 271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Guerin D, Sacquet J, Mandairon N, Jourdan F, Didier A (2009) Early locus coeruleus degeneration and olfactory dysfunctions in Tg2576 mice. Neurobiol Aging 30, 272–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].German DC, Nelson O, Liang F, Liang CL, Games D (2005) The PDAPP mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: Locus coeruleus neuronal shrinkage. J Comp Neurol 492, 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kalinin S, Polak PE, Lin SX, Sakharkar AJ, Pandey SC, Feinstein DL (2012) The noradrenaline precursor L-DOPS reduces pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 33, 1651–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Szot P, Van Dam D, White SS, Franklin A, Staufenbiel M, De Deyn PP (2009) Age-dependent changes in noradrenergic locus coeruleus system in wild-type and APP23 transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett 463, 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mehla J, Lacoursiere SG, Lapointe V, McNaughton BL, Sutherland RJ, McDonald RJ, Mohajerani MH (2019) Age-dependent behavioral and biochemical characterization of single APP knock-in mouse (APP(NL-G-F/NL-G-F)) model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 75, 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Latif-Hernandez A, Shah D, Craessaerts K, Saido T, Saito T, De Strooper B, Van der Linden A, D’Hooge R (2019) Subtle behavioral changes and increased prefrontal-hippocampal network synchronicity in APP(NL-G-F) mice before prominent plaque deposition. Behav Brain Res 364, 431–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Whyte LS, Hemsley KM, Lau AA, Hassiotis S, Saito T, Saido TC, Hopwood JJ, Sargeant TJ (2018) Reduction in open field activity in the absence of memory deficits in the App(NL-G-F) knock-in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res 336, 177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Adalbert R, Nogradi A, Babetto E, Janeckova L, Walker SA, Kerschensteiner M, Misgeld T, Coleman MP (2009) Severely dystrophic axons at amyloid plaques remain continuous and connected to viable cell bodies. Brain 132, 402–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chen H, Epelbaum S, Delatour B (2011) Fiber tracts anomalies in APPxPS1 transgenic mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease. J Aging Res 2011, 281274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Jawhar S, Trawicka A, Jenneckens C, Bayer TA, Wirths O (2012) Motor deficits, neuron loss, and reduced anxiety coinciding with axonal degeneration and intraneuronal Abeta aggregation in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 33, 196 e129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Stokin GB, Lillo C, Falzone TL, Brusch RG, Rockenstein E, Mount SL, Raman R, Davies P, Masliah E, Williams DS, Goldstein LS (2005) Axonopathy and transport deficits early in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 307, 1282–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wirths O, Weis J, Kayed R, Saido TC, Bayer TA (2007) Age-dependent axonal degeneration in an Alzheimer mouse model. Neurobiol Aging 28, 1689–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gunawardena S, Goldstein LS (2001) Disruption of axonal transport and neuronal viability by amyloid precursor protein mutations in Drosophila. Neuron 32, 389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Taru H, Iijima K, Hase M, Kirino Y, Yagi Y, Suzuki T (2002) Interaction of Alzheimer’s beta -amyloid precursor family proteins with scaffold proteins of the JNK signaling cascade. J Biol Chem 277, 20070–20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Chiba K, Araseki M, Nozawa K, Furukori K, Araki Y, Matsushima T, Nakaya T, Hata S, Saito Y, Uchida S, Okada Y, Nairn AC, Davis RJ, Yamamoto T, Kinjo M, Taru H, Suzuki T (2014) Quantitative analysis of APP axonal transport in neurons: Role of JIP1 in enhanced APP anterograde transport. Mol Biol Cell 25, 3569–3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Stokin GB, Almenar-Queralt A, Gunawardena S, Rodrigues EM, Falzone T, Kim J, Lillo C, Mount SL, Roberts EA, McGowan E, Williams DS, Goldstein LS (2008) Amyloid precursor protein-induced axonopathies are independent of amyloid-beta peptides. Hum Mol Genet 17, 3474–3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Gomez-Arboledas A, Davila JC, Sanchez-Mejias E, Navarro V, Nunez-Diaz C, Sanchez-Varo R, Sanchez-Mico MV, Trujillo-Estrada L, Fernandez-Valenzuela JJ, Vizuete M, Comella JX, Galea E, Vitorica J, Gutierrez A (2018) Phagocytic clearance of presynaptic dystrophies by reactive astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. Glia 66, 637–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, Merry KM, Shi Q, Rosenthal A, Barres BA, Lemere CA, Selkoe DJ, Stevens B (2016) Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 352, 712–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Rajendran L, Paolicelli RC (2018) Microglia-mediated synapse loss in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 38, 2911–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Cao S, Fisher DW, Rodriguez G, Yu T, Dong H (2021) Comparisons of neuroinflammation, microglial activation, and degeneration of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in APP/PS1 and aging mice. J Neuroinflammation 18, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Manocha GD, Floden AM, Miller NM, Smith AJ, Nagamoto-Combs K, Saito T, Saido TC, Combs CK (2019) Temporal progression of Alzheimer’s disease in brains and intestines of transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 81, 166–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Saito T, Saido TC (2018) Neuroinflammation in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol 9, 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Dournaud P, Boudin H, Schonbrunn A, Tannenbaum GS, Beaudet A (1998) Interrelationships between somatostatin sst2A receptors and somatostatin-containing axons in rat brain: Evidence for regulation of cell surface receptors by endogenous somatostatin. J Neurosci 18, 1056–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Johansson O, Hokfelt T, Elde RP (1984) Immunohistochemical distribution of somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the adult rat. Neuroscience 13, 265–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Palkovits M, Epelbaum J, Tapia-Arancibia L, Kordon C (1982) Somatostatin in catecholamine-rich nuclei of the brainstem. Neuropeptides 3, 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Dournaud P, Delaere P, Hauw JJ, Epelbaum J (1995) Differential correlation between neurochemical deficits, neuropathology, and cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 16, 817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Inoue M, Nakajima S, Nakajima Y (1988) Somatostatin induces an inward rectification in rat locus coeruleus neurones through a pertussis toxin-sensitive mechanism. J Physiol 407, 177–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Olpe HR, Steinmann MW, Pozza MF, Haas HL (1987) Comparative investigations on the actions of ACTH1-24, somatostatin, neurotensin, substance P and vasopressin on locus coeruleus neuronal activity. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 336, 434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Toppila J, Niittymaki P, Porkka-Heiskanen T, Stenberg D (2000) Intracerebroventricular and locus coeruleus microinjections of somatostatin antagonist decrease REM sleep in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 66, 721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Ferriero DM, Sheldon RA, Messing RO (1994) Somatostatin enhances nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 80, 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Paik S, Somvanshi RK, Kumar U (2019) Somatostatin-mediated changes in microtubule-associated proteins and retinoic acid-induced neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y cells. J Mol Neurosci 68, 120–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Shi TJ, Xiang Q, Zhang MD, Barde S, Kai-Larsen Y, Fried K, Josephson A, Gluck L, Deyev SM, Zvyagin AV, Schulz S, Hokfelt T (2014) Somatostatin and its 2A receptor in dorsal root ganglia and dorsal horn of mouse and human: Expression, trafficking and possible role in pain. Mol Pain 10, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Arenas E, Persson H (1994) Neurotrophin-3 prevents the death of adult central noradrenergic neurons in vivo. Nature 367, 368–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Arenas E, Trupp M, Akerud P, Ibanez CF (1995) GDNF prevents degeneration and promotes the phenotype of brain noradrenergic neurons in vivo. Neuron 15, 1465–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Counts SE, Mufson EJ (2010) Noradrenaline activation of neurotrophic pathways protects against neuronal amyloid toxicity. J Neurochem 113, 649–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Holm PC, Rodriguez FJ, Kresse A, Canals JM, Silos-Santiago I, Arenas E (2003) Crucial role of TrkB ligands in the survival and phenotypic differentiation of developing locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons. Development 130, 3535–3545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Quintero EM, Willis LM, Zaman V, Lee J, Boger HA, Tomac A, Hoffer BJ, Stromberg I, Granholm AC (2004) Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor is essential for neuronal survival in the locus coeruleus-hippocampal noradrenergic pathway. Neuroscience 124, 137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Zaman V, Li Z, Middaugh L, Ramamoorthy S, Rohrer B, Nelson ME, Tomac AC, Hoffer BJ, Gerhardt GA, Granholm AC (2003) The noradrenergic system of aged GDNF heterozygous mice. Cell Transplant 12, 291–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Mufson EJ, Kroin JS, Sendera TJ, Sobreviela T (1999) Distribution and retrograde transport of trophic factors in the central nervous system: Functional implications for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Neurobiol 57, 451–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Luellen BA, Bianco LE, Schneider LM, Andrews AM (2007) Reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor is associated with a loss of serotonergic innervation in the hippocampus of aging mice. Genes Brain Behav 6, 482–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Matsunaga W, Shirokawa T, Isobe K (2004) BDNF is necessary for maintenance of noradrenergic innervations in the aged rat brain. Neurobiol Aging 25, 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Nakai S, Matsunaga W, Ishida Y, Isobe K, Shirokawa T (2006) Effects of BDNF infusion on the axon terminals of locus coeruleus neurons of aging rats. Neurosci Res 54, 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Braun DJ, Kalinin S, Feinstein DL (2017) Conditional depletion of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor exacerbates neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. ASN Neuro 9, 1759091417696161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.