Abstract

Background:

Young onset dementia is associated with a longer time to diagnosis compared to late onset dementia. Earlier publications have indicated that atypical presentation is a key contributing factor to the diagnostic delay. Our hypothesis was that even the most common presentation of Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a substantial diagnostic delay in patients < 65 years.

Objective:

To determine the time to diagnosis, and time lags in the diagnostic pathway in typical young onset Alzheimer’s disease in central Norway.

Methods:

The main sources of patients were the databases at the Department of Neurology, University Hospital of Trondheim (St. Olav’s Hospital), and Department of Psychiatry, Levanger Hospital. Other sources included key persons in the communities, collaborating hospital departments examining patients with suspected cognitive impairment, and review of hospital records of all three hospitals in the area. Information on the time lags, and the clinical assessment, including the use of biomarkers, was collected from hospital notes. Caregivers were interviewed by telephone.

Results:

Time from first symptom to diagnosis in typical young onset Alzheimer’s disease was 5.5 years (n = 223, SD 2.8). Time from onset to contact with healthcare services (usually a general practitioner) was 3.4 years (SD 2.3). Time from contact with healthcare services to the first visit at a hospital was 10.3 months (SD 15.5). Time from first visit at a hospital to diagnosis was 14.8 months (SD 22.6). The analysis of cerebrospinal fluid core biomarkers was performed after 8.3 months (SD 20.9).

Conclusion:

Typical Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a substantial diagnostic delay in younger patients. Raising public awareness, and education of healthcare professionals on the aspects of young onset Alzheimer’s disease is warranted. CSF core biomarkers should be performed earlier in the hospital evaluation process.

Keywords: Clinical characteristics, delayed diagnosis, diagnosis, early onset Alzheimer’s disease, early onset dementia, young onset dementia

INTRODUCTION

Young onset dementia (YOD) is a term used to denote dementia that develops before the age of 65 [1]. Although many types of dementia may start before the age of 65, the most common cause of YOD is Alzheimer’s disease [2, 3]. Young onset AD, as in late onset dementia (onset over age 65), is characterized as a slow, progressive disease with preclinical and clinical phases, stretching over decades [4–6]. The prolonged nature, and resemblance to age-related slowing of cognition, hinder the recognition of symptoms as the disease develops from preclinical to clinical stages. The symptomatic period can be further divided into pre-dementia and dementia stages, where the latter is characterized by the disruption of daily life [7].

Objective symptoms of cognitive decline precede the diagnosis of dementia by up to 10 to 12 years, one study reporting the clinical pre-dementia phase as long as 18 years [8–10]. Until recently, the presence of dementia was required for the diagnosis of AD, prolonging the period of symptoms devoid of a proper explanation and diagnosis.

Time to diagnosis has been shown to be longer for patients with YOD when compared to late onset dementia [11]. Contributing factors to this include young age, having frontotemporal dementia, or any diagnosis other than AD [11–14]. A recent publication found that the total number of specialist services consulted increased the time to diagnosis, probably due to the complexity and diversity of young onset neurodegenerative disease and maybe also lack of competence even in specialist services [14–16].

The time from symptom onset to diagnosis is a difficult phase at any age, but additionally so when affecting persons under the age of 65 [17, 18]. Since the introduction of core biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the diagnosis of AD can be made during the pre-dementia phase of the disease, allowing patients and carers to plan for the future at an earlier stage [19]. Reducing the time from symptom onset to diagnosis will be of importance at any age when treatment emerges.

Many studies of the time to diagnosis in YOD include patients with a heterogeneity of dementias, and studies of AD often include multiple AD variants, both of which are associated with diagnostic delay. As the amnestic type of AD is the typical and most frequent presentation, factors contributing to an increased time to diagnosis for this particular subgroup of patients is important from a public health perspective. The main objective of this study was therefore to determine time from symptom to diagnosis in young onset AD with a typical presentation, where amnesia will be predominant in most cases. Our hypothesis was that even the commonest presentation of AD is associated with a substantial diagnostic delay in young patients.

The diagnostic assessment at hospitals often extends to months, even years, before a correct diagnosis is made [14, 16]. It is crucial that clinicians identify patients with young onset AD without further delay. A secondary objective was therefore to provide clinical characteristics of these patients as they present themselves at the hospital for the first time, rather than at the time of diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organization of healthcare services

Norway has a national health service that is readily accessible. All citizens are assigned to a general practitioner (GP), and access to hospital services is usually arranged through referrals by a GP. According to national guidelines, patients < 65 years with symptoms of dementia should be evaluated at an appropriate hospital department. In Norway, suspected cognitive impairment is commonly investigated in departments of neurology, geriatrics, or psychiatry.

The target area

The target area in the present study included both rural and urban areas whereof the city of Trondheim is the largest with approximately 200,000 people. There are three hospitals in Trøndelag; the University Hospital of Trondheim in which departments of neurology, geriatrics, and psychiatry see patients with symptoms of dementia, and two smaller hospitals in the northern region (the hospitals of Levanger and Namsos). These latter two hospitals have departments of neurology, geriatrics, and psychiatry, but patients with cognitive impairment are only evaluated at the Department of Geriatrics and Psychiatry. In Levanger, a memory clinic is situated at the Department of Psychiatry. The resident population of Trøndelag, consisting of approximately 470,000 people, does not differ significantly from that of the rest of the country [20].

Patients and recruitment process

Participants were recruited to the project “Young dementia in Trøndelag” (UngDemens i Trøndelag). The objective was to explore epidemiological aspects of YOD in a defined catchment area in central Norway. Main inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of dementia, or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD, with onset before the age of 65. The recruitment process was conducted from 2014 to 2018 making use of multiple case ascertainment, including community sources as well as multiple sources at hospital level. The main source of patients was the Department of Neurology at Trondheim University Hospital, and the Department of Psychiatry at the Hospital of Levanger, both main sites of referral for YOD in the target area. Additional sources included other hospitals and hospital units, and a wide range of community-based entities providing services to these patients. Information on the recruitment process is described elsewhere [3]. Data have already been published on the prevalence and incidence of YOD in the target area [2, 3]. A main finding of these studies was that almost every patient receiving a diagnosis of dementia was evaluated at a hospital.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In this study we included patients receiving a diagnosis of AD, regardless of the presence of dementia. Diagnoses were individually verified by researchers (MKA and SBS) as fulfilling criteria either for dementia or MCI due to AD [19, 21]. The verification process included both review of hospital notes and interview with a close caregiver.

Cases in which onset or time of the diagnosis could not be reliably identified were excluded.

Variables and data

Tables 1 and 2 give an overview of collected variables and recorded time lags in the diagnostic process.

Table 1.

Collected data

| Onset | Hospital | Inclusion in study | |

| Demographics | Age* | Age at diagnosis | Age at inclusion |

| Number and age of children | Year of diagnosis | Gender | |

| Employment status | MCI or dementia at diagnosis? | Education | |

| Arena of symptom recognition | Marital status | ||

| Community care | |||

| Disability status | |||

| Symptoms | Symptoms during initial three years | ||

| Diagnostic assessments | Cognitive tests: MMSE, clock drawing test, CERAD ten-item word test, Trail Making Test A/B | ||

| Biomarkers: CSF core biomarkers MRI | |||

| Number of contacts: Types of specialists involved Psychiatric evaluation and/or treatment before diagnosis? |

*Assessed by a combination of interview with caregiver and hospital records. CERAD, the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease.

Table 2.

Time lags

| •Time from disease onset to initial contact with a GP, or other healthcare professional. |

| •Time from the initial contact with a GP (or other) to a hospital referral. |

| •Time from a hospital referral to first consultation with a hospital physician. |

| •Time from first consultation with a hospital physician to recognition of a primary cognitive disorder. |

| •Time from recognition of a primary cognitive disorder to diagnosis of AD. |

| •Time from first consultation at a hospital to MMSE. |

| •Time from first consultation at a hospital to lumbar puncture and cerebral MRI. |

Age at onset was defined as the age when the first symptom(-s) appeared and was determined based on a combination of hospital notes and interview with a caregiver (most often a family member). In the loosely structured interview (conducted by the main researcher), substantial effort was made to reliably determine when symptoms appeared. In cases where hospital notes revealed that patients had recognized symptoms earlier than the caregiver, the age of onset was determined based on the patients recorded statements.

Arena of symptom recognition was dichotomized into work related and/or non-work related arenas. Information on these variables were based on information provided by the caregiver in the interview, and if addressed, in hospital notes.

Symptoms of AD were defined by a decline in premorbid functioning in the respective cognitive domain, as reported by the patient, caregiver, and/or by cognitive tests. Presence of symptoms was determined by all available data (caregiver interview, hospital notes, and cognitive tests). Poor performance on cognitive tests was not a requirement, as these often are not performed during the initial years. Also, subjective symptoms naturally precede verification on cognitive tests.

Initial contact with healthcare services was defined as the first time the patient, or others, reported symptoms to a physician. Recognition of a primary cognitive disorder by a hospital physician was defined as the moment the physician requested and/or performed an adequate examination of dementia symptoms.

Cognitive tests and MRIs were often conducted on multiple occasions during the hospital evaluation process. Only the first test score, and results from the first MRI, were registered in this study.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 223 patients met the inclusion criteria, whereof 142 (63.7%) were females and 81 (36.3%) males. Four patients with AD pathology in CSF core biomarkers, but atypical presentations were excluded; three patients with posterior cortical atrophy and one with frontotemporal dementia. Mean age at onset, age at diagnosis and age at study inclusion were 58.4 years (SD 4.3, range 47–64), 63.3 years (SD 4.7, range 50–73), and 66.4 years (SD 5.3, range 50–79), respectively. Patients received their diagnosis during the years 2001 to 2018, the majority between 2012 and 2017. Of the 45 patients (20.2%) who were diagnosed with MCI due to AD, 43 were diagnosed between 2012 and 2018. Interview with a close caregiver was performed in 211 (94.6%) of cases, with a mean time of 3.1 years post diagnosis.

Twenty-three patients (10.7%) had children under the age of 18, nine patients (4.2%) had children under the age of 12, and two (0.9%) had children under the age of six at the time of symptom onset (missing: eight). Almost two thirds of the patients (n = 142, 64.0%) were living at home, 43 (30.3%) of them receiving home care services. The rest of the patients (n = 80, 36.0%) were living in nursing homes. In one case the researchers were not able to determine the living situation.

Mean length of education was 11.5 years (SD 3.3, missing: two).

Almost a third of patients (n = 72, 32.4%) initiated medical evaluation themselves, while 18 (8.1%) did so in collaboration with their families. In other cases (n = 82, 36.9%), family members alone alerted the medical services. In 14 cases (6.3%) persons connected with the workplace (employer, co-workers, representatives from the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration) notified the GP. In 10 cases (4.5%) work-related persons contacted the GP in collaboration with family members, and in two cases they did so in collaboration with the patient. The GP suspected symptoms of dementia, and independently made the referral in only 11 cases (5.0%). In remaining cases (n = 13, 5.9%), others initiated the contact (such as friends, neighbors, hospital physicians). In one case, the researchers were not able to identify the initiating contact. Patients were referred to the hospital by their GP in 200 cases (89.7%).

A total of 156 patients (70.0%) were employed when symptoms emerged. Of these, 105 (67.3%) reported that symptoms of AD initially became apparent at work, before being observed in other arenas. Additionally, 26 patients (16.7%) reported symptoms emerging both at work and in non-work arenas concomitantly. In six cases (3.8%) the researchers were not able to identify the arena of debut.

More than six out of ten patients (n = 143, 65.0%) had public disability benefits at the time of study inclusion. Of these, only 80 (55.9%) were granted benefits because of acknowledged symptoms of AD, while 54 (37.8%) were on disability before they were diagnosed with AD, of which eight (14.8%) were granted benefits for non-AD symptoms that were later considered to be clearly AD-related. Four patients resigned from work due to covert symptoms of AD, resulting in financial loss. In three cases, the researchers were not able to determine the disability status.

Symptoms and diagnostic assessments

Table 3 shows symptoms during the initial three years of disease as reported by the patient, close family member, or by cognitive evaluation. Symptoms were typical for AD. In some patients, manifest amnesia was only evident subsequent to a period of diffuse symptoms.

Table 3.

Symptoms during the initial three years

| Symptom | Percentage of cases |

| Amnesia | 94.6 |

| Disorientation | 58.5 |

| Apathy | 50.4 |

| Depression | 38.4 |

| Apraxia | 33.5 |

| Aphasia | 25.4 |

| Emotional instability, irritability | 18.3 |

| Personality changes | 15.2 |

Table 4 gives an overview of details on cognitive tests, as well as biomarkers.

Table 4.

Cognitive tests and biomarkers

| Cognitive test | N | % | Mean score | Range |

| MMSE | 223 | 100 | 23.0* (SD 5.0) | 8–30 |

| %pathological | ||||

| Clock drawing test | 219 | 98.2 | 62.3 | |

| CERAD ten-item word test | ||||

| Immediate recall | 142 | 63.7 | 88.7 | |

| Delayed recall | 138 | 61.9 | 95.7 | |

| Recognition | 84 | 37.7 | 92.9 | |

| Trail Making Test | ||||

| A | 194 | 87.0 | 45.9 | |

| B | 191 | 85.7 | 76.3 | |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| CSF core biomarkers | 191 | 85.7 | ||

| Aβ42 | 67.5 | |||

| Phosphorylated tau protein | 61.8 | |||

| Total tau protein | 73.8 | |||

| All three | 39.8 | |||

| Cerebral MRI** | 214 | 96.0 | 46.3 |

*50.4%scored≥26 points. **The remaining nine patients not receiving an MRI were evaluated by CT. CERAD, the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease.

Number of contacts and psychiatric evaluation

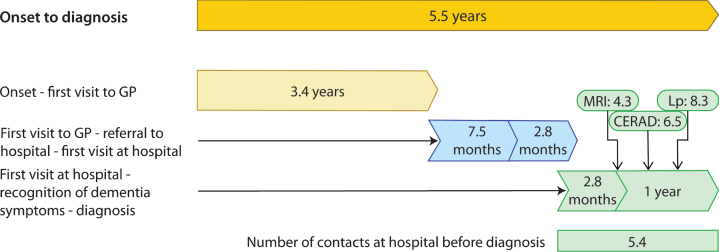

The mean number of hospital evaluation points in the diagnostic workup is illustrated in Fig. 1. The mean number of visits before the physician acknowledged the symptoms as AD-related, and initiated investigation of a cognitive disorder, was 2.0 (SD 4.7, range 1–4). Eighteen patients (8.1%) received evaluation and/or treatment for psychiatric symptoms with a mean duration of 15.1 months (SD 16.4, range 1–48 months).

Fig. 1.

Time lags from symptom to diagnosis of young onset Alzheimer’s disease. GP, general practitioner; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; Lp, Lumbar puncture; CERAD, Consortium. Time from onset to diagnosis; n = 223, range 2–17, SD 2.8 (years). Time from symptom to contact; n = 188, range 6–132, SD 2.3 (months). Time from contact to referral; n = 182, range 0–110, SD 15.2 (months). Time from referral to first visit at hospital; n = 203, range 0–52, SD 3.8 (months). Time from first visit to hospital to recognition of dementia symptoms; n = 222, range 0–109, SD 12.1, months). Time from primary recognition of dementia symptoms to diagnosis; n = 223, range 0–140, SD 20.1 (months). Time from first visit to hospital to MRI; n = 214, range 0–125, SD 13.8 (months). Time from first visit to hospital to CERAD; n = 142, range 0–136, SD 19.5 (months). Time from first visit to hospital to lumbar puncture; n = 191, range 0–139, SD 20.9 (months).

Types of specialists involved in assessing the diagnosis

A diagnosis of AD was made at a department of neurology (n = 107, 48.0%), psychiatry (n = 67, 30.0%), or internal medicine (mainly by geriatric physicians, n = 49, 22.0%). In 67 cases (30.0%) more than one department was involved in the diagnostic process (range 2–6).

Time lags

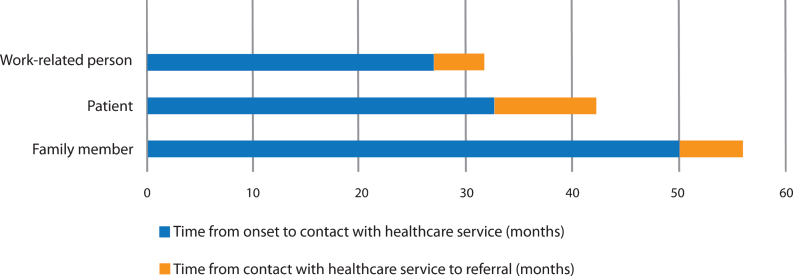

Mean time lags, and number of contacts at the hospital before the diagnosis was made, are visualized in Figs. 1 and 2. The time lags illustrate the pathway to diagnosis. In cases where the GP was not contacted, and he/she independently issued a referral to the hospital, the time from symptom debut to referral was 5.0 years (n = 11, range 5–204, SD 55.3, not illustrated in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pre-hospital time lags according to person initiating contact with healthcare services. Work-related person: Time from onset to contact; n = 13, range 12–72, SD 19.4. Time from contact to referral; n = 13, range 0–12, SD 3.2. Patient: Time from onset to contact; n = 68, range 6–108, SD 21.5. Time from contact to referral; n = 66, range 0 –110, SD 20.5. Family member: Time from onset to contact; n = 76, range 12–132, SD 29.9. Time from contact to referral; n = 75, range 0–51, SD 9.1.

Mean time from first contact with a hospital to the performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) ten-item word test was 2.8 months (range 0–109 months, SD 12.3) and 6.5 months (range 0–136, SD 19.5), respectively. A total of 191 patients (85.7%) were evaluated with MMSE at the first visit. The mean time from first visit to a hospital to the performance of MMSE for patients who received a psychiatric evaluation and/or treatment was 21.0 months (range 0–109, SD 29.3). Almost half of MRIs (n = 104, 48.6%) were performed before the first visit to a hospital. Of these, 47 (45.2%) were not pathological, and 22 (21.2%) only marginally pathological (medial temporal atrophy classified as Scheltens 2 [22]).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest study on the time from symptom debut to diagnosis in patients with typical AD with young onset. Diagnoses were individually verified with a high level of clinical accuracy, including biomarkers in over 80%of the cases. The geographical target area covers both urban and rural areas, has three hospitals of varying sizes providing approximately equal access to healthcare, and the resident population is largely representative for that of the rest of the country [20]. In our opinion, the findings of this study are both relevant and applicable for other parts of the world with a similar healthcare system.

The main finding in this study is a substantial diagnostic delay of 5.5 years for patients with typical young onset AD. This is considerably longer than previous studies in which delays have ranged from 1.5 to 4.2 years (Table 5) [11–14]. Low age and clinical heterogeneity have been hypothesized to be factors associated with a longer time to diagnosis in patients under 65 years, but do not offer plausible explanations for the time to diagnosis in the present study [1, 16, 23]. Patients in both this and the previous studies had predominantly amnestic symptoms. In addition, age at onset and age at diagnosis were higher in the present study compared to the two studies that provided this information for typical AD [12, 14]. With the exception of one study from Australia, all studies were conducted in a population-based setting, indicating that healthcare capacity was not a source of bias between them [14].

Table 5.

Time to diagnosis in young onset AD with typical progression in various studies

| Study | Country | Diagnosis | N | Mean time to diagnosis (y) |

| Current study | Norway | MCI/ dementia | 223 | 5.5 |

| Loi et al., 2020 [14] | Australia | Dementia | 55 | 2.9 |

| Draper et al., 2016 [13] | Australia | Dementia | 47 | 1.5* |

| Van Vliet et al., 2013 [11] | The Netherlands | Dementia | 139 | 4.2 |

| Rosness et al., 2008 [12] | Norway | Dementia | 37 | 3.3 |

*Median time.

There may be various factors underlying the delays in the diagnostic pathway. Segmentation of the time to diagnosis into time lags may offer greater insight for understanding the fundamentals of diagnostic delay.

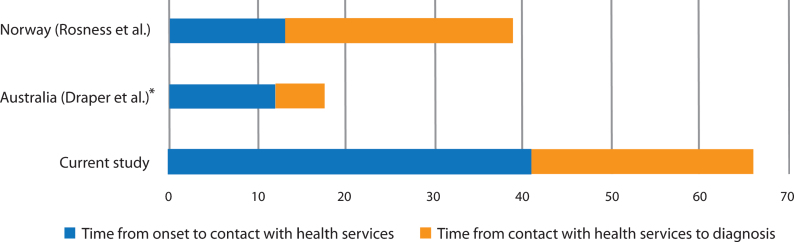

Time lag prior to contact with medical services

A significant finding in our study was the prolonged time from onset of symptoms to the time that patients or their family requested a medical evaluation. On average, the symptoms had persisted for 3.4 years before contact with medical services was initiated, accounting for well over half the total delay. Although research on this time lag is scarce, it is substantially longer than two other studies (from Norway and Australia) reporting approximately 12–13 months (Fig. 3) [12, 13]. There could be several reasons for this. The slow and covert nature of the onset of symptoms impedes timely recognition. The actual debut of symptoms might therefore be easier to identify retrospectively after a diagnosis has been made, providing caregivers with the opportunity to reflect upon when symptoms first emerged. In the present study, the onset of symptoms was assessed by asking proxies at a later stage compared to the earlier study from Norway; 3.1 years versus 1.9 months after diagnosis [12]. It was a consistent finding in the current study that onset was considered to be earlier when caregivers were interviewed by the researcher during a later phase. Not infrequently a discrepancy of several years was reported when compared to the hospital notes, contributing to a significant increase both in the time before contact, and in consequence, to the total diagnostic delay. A study from the United States showed that time from onset to problem recognition in AD increased with the time that had passed since the diagnosis, caregivers reporting a mean time of 2.25 years if the diagnosis was made 49 months or more prior to the interview [24]. Methodological differences might therefore be a source of substantial bias between studies, those benefitting from hindsight perhaps providing a more accurate estimation.

Fig. 3.

Time lags in other studies. *Median.

In the effort to reduce time to diagnosis, this study demonstrates the relevance of raising public awareness of the typical symptoms of young onset AD. The amnestic variant of AD is the most common subtype of YOD, and any successful effort to diminish the burden of diagnostic delay in this group of patients is therefore likely to have a greater impact on public health. The beneficial effects of cholinesterase inhibitors in AD, especially if implemented in earlier phases, may additionally provide incentives for patients and caregivers to seek an early diagnosis [25–29]. Public knowledge on the availability of pharmacological treatment should therefore be an important priority for healthcare authorities.

Anosognosia is a common symptom in AD. Patients with young onset AD have a higher level of awareness of their symptoms in earlier stages than patients with late onset disease [30]. In the present study, approximately 40%of patients sought a medical opinion for their symptoms themselves, demonstrating that many patients do acknowledge emerging symptoms. Moreover, they recognize them significantly earlier than their family members. Almost 70%of patients were employed when symptoms appeared, and more than two thirds of these reported difficulty at work before symptoms became apparent elsewhere, consistent with the finding that persons related to the workspace acknowledged cognitive changes sooner than family members. However, only a small percentage of employers actually notified the GP, which was the initial point of contact in most cases. Consistent with the findings in this study, it has been shown that patients with AD have significantly more severe work-related difficulties compared to patients with frontotemporal dementia [12].

Only four patients described financial loss due to the diagnostic delay. The potential effects of economic considerations, and/or perceived stigma, both of which are aspects associated with a reluctance to pursue a diagnosis, were regrettably not explored in the current study. Previous studies have found an age-related association between YOD and these factors, and one study found that persons with YOD leave their jobs with a hazard ratio of 2.26 compared to healthy controls, but additional research is warranted [31–33].

Time lag following contact with medical services

After patients and/or others contact the healthcare services, the healthcare system is responsible for any subsequent delays. In the present study, physicians used more than two years to diagnose AD.

The role of the GP

The second step in the diagnostic pathway is the referring physician. Patients were referred to a hospital with a substantial delay of 7.5 months, occasionally stretching up to nine years. In the most extreme instances, the patients were mainly referred for the evaluation and treatment of behavioral disturbances during later stages of dementia, the underlying diagnosis being a secondary objective. A prolonged period from presenting to a medical doctor until specialist referral has been previously shown in a study from Norway [12]. In this latter study the delay was even longer (19.1 months). It is worth noticing that less than 5%of the patients in the present study were independently recognized by the GP. In these cases, time from onset to referral was 5.0 years, indicating that GPs might not be trained to detect cognitive impairment at earlier stages. Interestingly, in cases where the patients themselves contacted the GP, the GP referred patients to the hospital later compared to cases where the GP was contacted by employers or family members. The reasons for this may be complex but indicate that GPs are less alert if patients report cognitive symptoms themselves. This contrasts with our findings that patients acknowledge symptoms earlier than their families.

Nevertheless, a time lag of seven months from the time of contact with the GP to the issuing of a referral, identifies an obstacle to early diagnosis. Educating GPs on the particular aspects of young onset AD, such as the increasing incidence from the threshold age of 50, symptom profile, a high level of patient awareness, arena of debut, and the positive effects of cholinesterase inhibitors might be warranted.

The role of the hospital

Patients were evaluated at the hospital three months after a referral was issued, such that it took as long as ten months from patient contact with medical services to receiving a clinical assessment of their symptoms. An additional three months passed before hospital physicians recognized the symptoms as being primarily cognitive, thus exceeding a year from initial contact to an adequate examination. In total, hospitals spent nearly one and a half years with over five points of contact with the patient, to correctly identify AD. This is less than a previous study from Norway, but more than a study from Australia (Fig. 3). Almost one third of patients were evaluated by physicians of different specialties, ranging from two to six departments, displaying a diagnostic pathway “from pillar to post”, as characterized in an early study from England, and reaffirmed in a more recent study from Australia [14, 16]. In this respect, it is clear that there remains considerable room for improvement.

Cognitive tests are tools for documenting cognitive decline over time. As hospitals spent a substantial time evaluating these patients, occasionally extending over several years, rather than focusing on test scores at the time of diagnosis, as many studies do, this study provides data on test scores when conducted for the first time [11, 34]. Consistently, mean MMSE score was higher in the present study when compared to a study on young onset AD and a study of YOD in which MMSE scores were registered at the time of diagnosis (23.0 versus 21.3 and 21.1, respectively) [11, 12]. Test scores have previously been shown to be associated with age, younger patients doing better than older patients at the time of diagnosis [11, 34, 35]. MMSE was conducted relatively early in the investigatory process, and the majority of patients performed well at this point. MMSE therefore seemed to have the potential effect of freezing further investigations of cognitive impairment, and paradoxically, delaying the diagnosis. The CERAD ten-item word test was largely pathological when performed for the first time but was not performed until 6.5 months into the investigative process. Clock drawing test and Trail Making Tests were less sensitive, and not infrequently normal.

Relatively intact cognitive capabilities could partly be a reflection of the substantial portion of patients (20%, n = 45) who were diagnosed with MCI due to AD. The ability to diagnose AD in the predementia stages of the condition according to new diagnostic criteria is a valuable step in reducing diagnostic delay.

As large parts of the world continue to develop as societies with high cognitive demands, it is possible to hypothesize that patients at all ages, younger and employed patients in particular, will present themselves to healthcare services at earlier, and less impaired phases in the future. Hospital physicians will need to adjust to this reality.

MRI scans were available to the hospital physician by the first visit in approximately half the cases, and they were often normal. A low diagnostic value of imaging in early stages of young onset AD agrees with previous studies [36]. The analysis of CSF core biomarkers was performed at a later stage (8.3 months), probably precipitating a diagnosis of AD in the months thereafter. CSF analysis, in combination with the CERAD ten-item word test, might therefore be the key to early diagnosis, and in our opinion should be a priority in the medical evaluation of suspected cognitive impairment.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the challenges of diagnosing patients with the most frequent subtype of YOD. A time to diagnosis of 5.5 years affects quality of life for patients and their families and impedes the success of any emerging pharmacological treatment in the future. The study identified several obstacles to the rapid diagnosis of young onset AD, some concerning public and family awareness, and multiple delays originating within the medical services, some of them overlapping. Public healthcare authorities could play a key role in educating the public and relevant parts of the medical community. A survey from Australia found a year’s decrease in the diagnostic delay for patients evaluated in a specialized YOD service, calling for a more specialized assessment of young patients with cognitive symptoms [14]. Although there are several points of target, as the current study indicates, the current authors share this view.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank patients and their caregivers for participating in this study.

The study was supported by grants from the Norwegian National Association for Public Health (ref 7-058.2).

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/21-0090r1).

REFERENCES

- [1].Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD (2010) The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol 9, 793–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kvello-Alme M, Brathen G, White LR, Sando SB (2020) Incidence of young onset dementia in central Norway: A population-based study. J Alzheimers Dis 75, 697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kvello-Alme M, Brathen G, White LR, Sando SB (2019) The prevalence and subtypes of young onset dementia in central Norway: A population-based study. J Alzheimers Dis 69, 479–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vos SJB, Xiong C, Visser PJ, Jasielec MS, Hassenstab J, Grant EA, Cairns NJ, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM (2013) Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and its outcome: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol 12, 957–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr., Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].American Psychiatric Association (1994) DSM-IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. American Psychiatric Organization.

- [8].Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Weuve J, Barnes LL, Evans DA (2015) Cognitive impairment 18 years before clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease dementia. Neurology 85, 898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Howieson DB, Carlson NE, Moore MM, Wasserman D, Abendroth CD, Payne-Murphy J, Kaye JA (2008) Trajectory of mild cognitive impairment onset. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 14, 192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Johnson DK, Storandt M, Morris JC, Galvin JE (2009) Longitudinal study of the transition from healthy aging to Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 66, 1254–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Bakker C, Pijnenburg YA, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Koopmans RT, Verhey FR (2013) Time to diagnosis in young-onset dementia as compared with late-onset dementia. Psychol Med 43, 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rosness TA, Haugen PK, Passant U, Engedal K (2008) Frontotemporal dementia: A clinically complex diagnosis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23, 837–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Draper B, Cations M, White F, Trollor J, Loy C, Brodaty H, Sachdev P, Gonski P, Demirkol A, Cumming RG, Withall A (2016) Time to diagnosis in young-onset dementia and its determinants: The INSPIRED study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 31, 1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Loi SM, Goh AMY, Mocellin R, Malpas CB, Parker S, Eratne D, Farrand S, Kelso W, Evans A, Walterfang M, Velakoulis D (2020) Time to diagnosis in younger-onset dementia and the impact of a specialist diagnostic service. Int Psychogeriatr, doi: 10.1017/S1041610220001489. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [15].Woolley JD, Khan BK, Murthy NK, Miller BL, Rankin KP (2011) The diagnostic challenge of psychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative disease: Rates of and risk factors for prior psychiatric diagnosis in patients with early neurodegenerative disease. J Clin Psychiatry 72, 126–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Williams T (2001) From pillar to post - a study of younger people with dementia. Psychiatr Bull 25, 384–387. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cabote CJ, Bramble M, McCann D (2015) Family caregivers’ experiences of caring for a relative with younger onset dementia: A qualitative systematic review. J Fam Nurs 21, 443–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].van Vliet D, de Vugt ME, Bakker C, Koopmans RT, Pijnenburg YA, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Verhey FR (2011) Caregivers’ perspectives on the pre-diagnostic period in early onset dementia: A long and winding road. Int Psychogeriatr 23, 1393–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, DeKosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O’Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P (2007) Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol 6, 734–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Trøndelag Fylkeskommune (2016) Trøndelag i tall. https://www.trondelagfylke.no/contentassets/1889712535bd4178b8626f300c04cae7/trondelag-i-tall-2016.pdf.

- [21].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 34, 939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Scheltens P, Leys D, Barkhof F, Huglo D, Weinstein HC, Vermersch P, Kuiper M, Steinling M, Wolters EC, Valk J (1992) Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in “probable” Alzheimer’s disease and normal ageing: Diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 55, 967–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Palasi A, Gutierrez-Iglesias B, Alegret M, Pujadas F, Olabarrieta M, Liebana D, Quintana M, Alvarez-Sabin J, Boada M (2015) Differentiated clinical presentation of early and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: Is 65 years of age providing a reliable threshold? J Neurol 262, 1238–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Knopman D, Donohue JA, Gutterman EM (2000) Patterns of care in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Impediments to timely diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc 48, 300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Loy C, Schneider L (2004) Galantamine for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Birks J, Grimley Evans J, Iakovidou V, Tsolaki M, Holt FE (2009) Rivastigmine for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Birks J, Harvey RJ (2006) Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD001190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [28].Winblad B, Wimo A, Engedal K, Soininen H, Verhey F, Waldemar G, Wetterholm AL, Haglund A, Zhang R, Schindler R (2006) 3-year study of donepezil therapy in Alzheimer’s disease: Effects of early and continuous therapy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 21, 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, Georges J, McKeith IG, Rossor M, Scheltens P, Tariska P, Winblad Efns B (2007) Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline. Eur J Neurol 14, e1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Van Vliet D, De Vugt ME, Köhler S, Aalten P, Bakker C, Pijnenburg YAL, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Koopmans RTCM, Verhey FRJ (2013) Awareness and its association with affective symptoms in young-onset and late-onset alzheimer disease: A prospective study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 27, 265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ashworth R (2020) Perceptions of stigma among people affected by early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Health Psychol 25, 490–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Moniz-Cook ED, Woods RT, De Lepeleire J, Leuschner A, Zanetti O, de Rotrou J, Kenny G, Franco M, Peters V, Iliffe S (2005) Factors affecting timely recognition and diagnosis of dementia across Europe: From awareness to stigma. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20, 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sakata N, Okumura Y (2017) Job loss after diagnosis of early-onset dementia: A matched cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis 60, 1231–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Garre-Olmo J, Genís Batlle D, Del Mar Fernández M, Marquez Daniel F, De Eugenio Huélamo R, Casadevall T, Turbau Recio J, Turon Estrada A, López-Pousa S (2010) Incidence and subtypes of early-onset dementia in a geographically defined general population. Neurology 75, 1249–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pradier C, Sakarovitch C, Le Duff F, Layese R, Metelkina A, Anthony S, Tifratene K, Robert P (2014) The mini mental state examination at the time of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders diagnosis, according to age, education, gender and place of residence: A cross-sectional study among the French National Alzheimer database. PLoS One 9, e103630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Falgas N, Sanchez-Valle R, Bargallo N, Balasa M, Fernandez-Villullas G, Bosch B, Olives J, Tort-Merino A, Antonell A, Munoz-Garcia C, Leon M, Grau O, Castellvi M, Coll-Padros N, Rami L, Redolfi A, Llado A (2019) Hippocampal atrophy has limited usefulness as a diagnostic biomarker on the early onset Alzheimer’s disease patients: A comparison between visual and quantitative assessment. Neuroimage Clin 23, 101927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]