Abstract

Background

Infections caused by Enterococcus hirae are common in animals, with instances of transmission to humans being rare. Further, few cases have been reported in humans because of the difficulty in identifying the bacteria. Herein, we report a case of pyelonephritis caused by E. hirae bacteremia and conduct a literature review on E. hirae bacteremia.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old male patient with alcoholic cirrhosis and neurogenic bladder presented with fever and chills that had persisted for 3 days. Physical examination revealed tenderness of the right costovertebral angle. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) of the patient’s blood and urine samples revealed the presence of E. hirae, and pyelonephritis was diagnosed. The patient was treated successfully with intravenous ampicillin followed by oral linezolid for a total of three weeks.

Conclusion

The literature review we conducted revealed that E. hirae bacteremia is frequently reported in urinary tract infections, biliary tract infections, and infective endocarditis and is more likely to occur in patients with diabetes, liver cirrhosis, and chronic kidney disease. However, mortality is not common because of the high antimicrobial susceptibility of E. hirae. With the advancements in MALDI-TOF MS, the number of reports of E. hirae infections has also increased, and clinicians need to consider E. hirae as a possible causative pathogen of urinary tract infections in patients with known risk factors.

Keywords: Enterococcus hirae, Urinary tract infection, Alcoholic cirrhosis, Case report

Background

Enterococcus hirae primarily causes zoonosis [1, 2], with human infections being relatively rare. Nevertheless, pyelonephritis [3–5], infective endocarditis [6–11], and biliary tract infections [5, 12] due to E. hirae have been reported in human patients. Although E. hirae has been found to cause these severe diseases in humans, few cases have been reported because of the difficulty in identifying the bacteria, and the lack of comprehensive reports on clinical characteristics and treatments [3].

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has recently emerged as an important diagnostic tool, characterized by its high speed, ease of use, and low per sample cost compared to those of conventional diagnostic tools [13]. Therefore, greater progress in the analysis of a variety of bacterial species that have been difficult to identify in the past is expected [13]. In a case of urinary tract infection, E. hirae was rapidly and correctly identified using MALDI-TOF MS, without any complementary tests [14]. Here, we report a case of bacteremia secondary to pyelonephritis caused by E. hirae identified by MALDI-TOF MS, which was successfully treated with ampicillin followed by linezolid. Furthermore, we conducted a literature review on bacteremia caused by E. hirae.

Case presentation

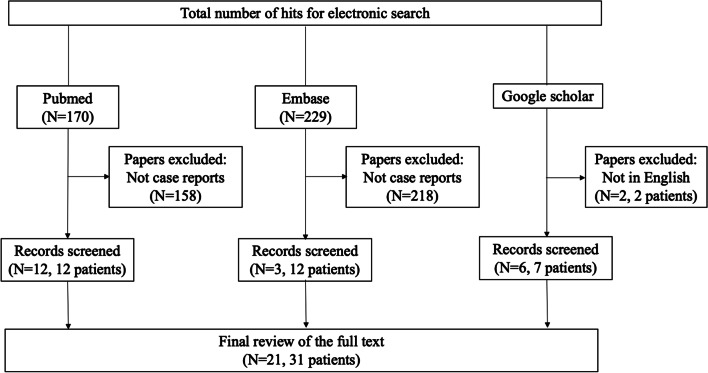

A 57-year-old male with a history of neurogenic bladder caused by cerebral palsy presented to our emergency department with fever and chills that had persisted for 3 days. He had a history of alcoholic cirrhosis classified as Child–Pugh class C treated with rifaximin, lactulose, and branched-chain amino acid supplementation. The patient reported daily consumption of 500 mL of Shochu (a traditional Japanese distilled spirit). He had no allergies or significant family history. He was unemployed and denied any recent contact with animals. The patient was diagnosed with a urinary tract infection at a nearby clinic and was prescribed oral cefcapene 2 days before admission. The patient was conscious on admission with a Glasgow Coma Scale of E4V5M6, body temperature of 36.9 °C, blood pressure of 104/52 mmHg, pulse rate of 82/min, respiratory rate of 20/min, and oxygen saturation of 95% on room air. On physical examination, tenderness of the right costovertebral angle was noted. Laboratory findings revealed a normal white blood cell (WBC) count of 6,000 /μL, hemoglobin level of 12.3 g/dL, platelet count of 48,000 /μL, creatinine level of 0.92 mg/dL, serum albumin level of 2.9 g/dL, total bilirubin level of 2.7 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein level of 13 mg/dL. Urinalysis showed protein 2 + , occult blood 2 + , and WBC 2 + . Urine Gram staining revealed gram-positive chains with phagocytosis. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen revealed mild swelling of the kidneys, increased surrounding fat tissue density, and a dull edge and uneven surface of the liver (Fig. 1). We first administered 1 g of intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone every 24 h. On day 2, we added 2 g of IV ampicillin every 4 h because streptococci were cultured from blood and urine samples obtained on admission (BacT/ALERT FA Plus, BacT/ALERT 3D [bioMérieux Inc.]). On day 4, a transthoracic echocardiogram revealed no evidence of infective endocarditis. On day 5, final culture results revealed E. hirae by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (MALDI Biotyper [Bruker Daltonics]) and VITEK2 Compact (bioMérieux Inc.). The minimum inhibitory concentrations measured by MicroScan WalkAway 96 Plus and PC1J panel(Beckman Coulter Inc.) for this strain were as follows: penicillin G 0.25 μg/mL, ampicillin 0.25 μg/mL, vancomycin 1 μg/mL, levofloxacin ≤ 0.5 μg/mL, teicoplanin ≤ 2 μg/mL, and linezolid 2 μg/mL (Table 1). We switched to ampicillin IV (2 g every 6 h). Blood cultures performed on day 5 were negative. Because his low-grade fever persisted, we switched to oral linezolid 600 mg every 12 h on day 11, considering possible drug fever. Thereafter, the patient defervesced and was discharged on day 15. He completed a course of oral linezolid for 3 weeks in total, and his condition resolved without any relapse of symptoms at the 10-month follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic images revealing heterogeneous enhancement of both kidneys in A, and a liver with a blunt edge and irregular surface in B

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the Enterococcus hirae isolated from blood culture in this case

| Antimicrobials | MIC (μg/mL) | Susceptibilitya |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin G | 0.25 | N/A |

| Ampicillin | 0.25 | Susceptible |

| Vancomycin | 1 | Susceptible |

| Levofloxacin | ≤ 0.5 | Susceptible |

| Teicoplanin | ≤ 2 | Susceptible |

| Linezolid | 2 | Susceptible |

MIC Minimal inhibitory concentration

aBased on the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) Clinical Breakpoints v.11.0, for Enterococcus spp.[15]

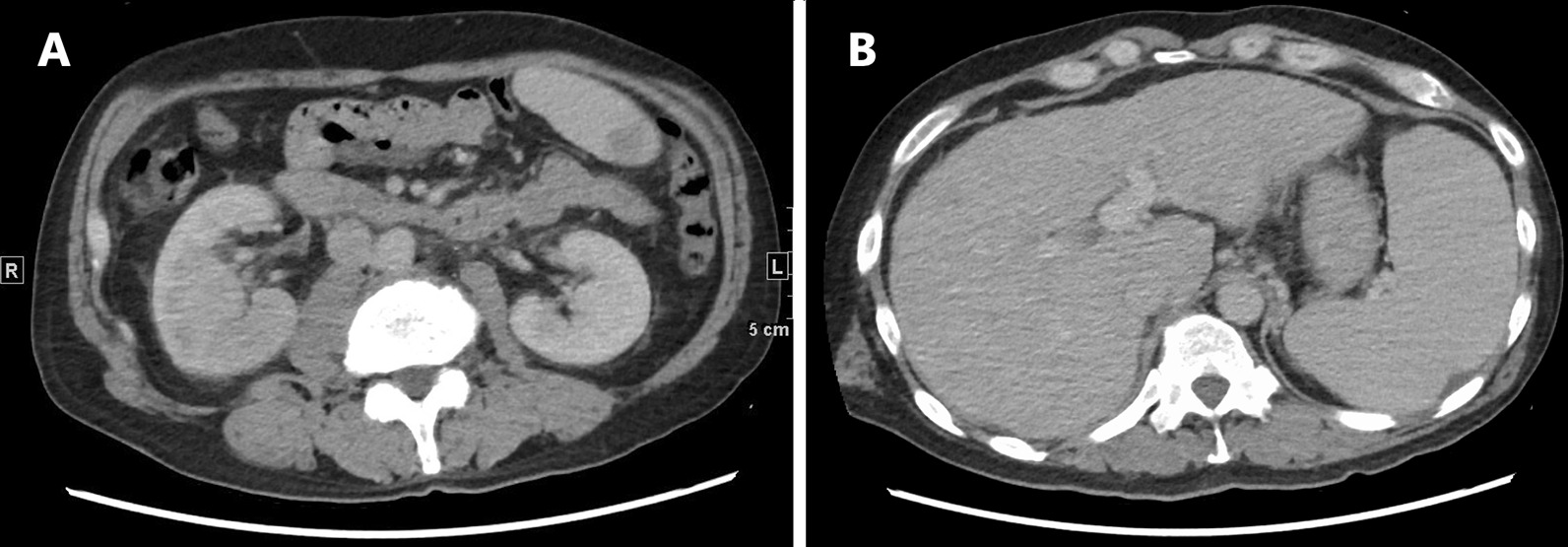

Methods of literature review

Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of database records, retrieved full texts for eligibility assessment, and extracted data from these case reports. We ran searches on the PubMed database (up to May 2020) using the keywords ((("Enterococcus hirae"[Mesh]) OR ("Enterococcus hirae"[TW]) OR (hirae[TIAB])) AND ((Bacteremia[MH]) OR (bacteremia*[TIAB] OR bacteraemia*[TIAB]))) OR ((("Enterococcus hirae"[Mesh]) OR ("Enterococcus hirae"[TW]) OR (hirae[TIAB])) AND Humans[MH]), and the Embase database using the keywords (('bacteremia'/exp OR 'gram negative sepsis'/exp OR bacteraemia* OR bacteremia*) AND ('enterococcus hirae'/exp OR hirae)) OR (('enterococcus hirae'/exp OR hirae) AND [humans]/lim). PubMed and Embase searches generated 170 and 229 articles, respectively. Of these, 158 and 218 articles from PubMed and Embase, respectively, were excluded because they were not case reports (Fig. 2). We searched Google Scholar and identified eight more human cases. Manuscripts not written in English were excluded. Finally, we reviewed 21 articles that included 31 strains from human sources.

Fig. 2.

Literature review flow chart

Discussion and conclusion

Enterococcus hirae was first identified by Farrow et al. in 1985 [16]. It has been reported that although animal species such as chickens, rats, birds, and cats are commonly found to be infected [1, 2], human infections are relatively rare [17]. Only 31 human cases of E. hirae have been reported (Table 2). Of these, urinary tract infections [3–5, 12, 14, 18], biliary tract infections [5, 12], and infective endocarditis [6–11] accounted for the majority of cases, with catheter-related bloodstream infections [12, 19], peritonitis [20, 21], splenic abscess [22], and pneumonia [17] also being reported. Patients were predominantly male (n = 20, 64.5%), similar to predominance in infections caused by other Enterococcus spp. [23], Furthermore, no age trend was observed (median: 63 years) [23]. The common underlying diseases were diabetes mellitus (n = 12, 39%), liver cirrhosis (n = 4, 13%), and chronic kidney disease (n = 4, 13%). Occurrence of diabetes mellitus and liver cirrhosis was consistent with previous reports of Enterococcus spp. Malignant tumors were found to be less common [23]. This case of a middle-aged male with underlying alcoholic cirrhosis and chronic kidney disease was consistent with the trend uncovered in the literature review.

Table 2.

Summary of the previously reported human cases with Enterococcus hirae

| Case | References | Age | Gender | Year | Underlying diseases | Chief complaint | Method of E. hirae identification | Diagnosis | treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gilad et al. [24] | 49 | Male | 1998 | ESRD with hemodialysis, Indwelling central venous catheter | Fever | Rapid ID 32 Strep system | Septicemia | VCM + TOB | Complete resolution |

| 2 | Tan et al. [12] | 82 | Female | 2000 | DM | N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis | Urinary tract infection | AMPC + GEM | Complete resolution |

| 3 | Tan et al. [12] | 80 | Male | 2001 | Biliary tract disease | N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis |

Biliary tract infection |

CMZ + Operation |

Complete resolution |

| 4 | Poyart et al. [6] | 72 | Male | 2002 | Coronary artery disease | Fever, Chills, Progressive malaise, Generalized weakness | (sodA gene) sequencing | Native valve Endocarditis |

ABPC + GM 4 weeks, RFP 3 weeks → ABPC + GM po Readmission: VCM + GM 6 weeks → ABPC po total 8 weeks |

Complete resolution |

| 5 | Tan et al. [12] | 50 | Male | 2002 | ESRD | N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis | Primary bacteremia | VCM | Complete resolution |

| 6 | Tan et al. [12] | 55 | Male | 2003 | N/A | N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis | Urinary tract infection | ABPC | Complete resolution |

| 7 | Tan et al. [12] | 63 | Male | 2004 | Biliary tract disease | N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis | Biliary tract infection | ABPC/SBT + biliary drainage | Complete resolution |

| 8 | Tan et al. [12] | 69 | Female | 2004 | N/A | N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis | Urinary tract infection | ABPC/SBT | Complete resolution |

| 9 | Tan et al. [12] | 57 | Male | 2006 | Tongue cancer | N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis |

Catheter Associate infection |

VCM + Removal of catheter | Complete resolution |

| 10 | Vinh et al. [9] | 80 | Male | 2006 | DM, Hypercholesterolemia, Coronary artery disease, Resection of malignant colonic polyp | Dyspnea, Vague epigastric discomfort | VITEK 2 automated system (bioMériux) | Native-valve bacterial endocarditis | ABPC 6 weeks after aortic replacement | Complete resolution |

| 11 | Tan et al. [12] | 59 | Male | 2008 | Pancreatic cancer with obstructive jaundice | N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis | Biliary tract infection | VCM + IPM + Surgical intervention | Died |

| 12 | Tan et al. [12] | 69 | Female | 2008 |

Lung cancer on chemotherapy |

N/A | 6.5% NaCl tolerance and growth on bile-esculin agar with esculin hydrolysis |

CatheterAssociate infection |

VCM + Removal of catheter |

Complete resolution |

| 13 | Canalejo et al. [25] | 55 | Male | 2008 | DM | Low back pain, Fever, Chills | VITEK 2 automated system (bioMériux), rRNA gene sequencing | Spondylodiscitis | ABPC + GM 8 Weeks → Surgery → LVFX po + ST 6 months | Complete resolution |

| 14 | Nicolosi et al. [26] | 63 | Male | 2009 | N/A | N/A | Unknown | Bacteremia | N/A | N/A |

| 15 | Chan et al. [5] | 62 | Female | 2010 | N/A | Fever, Chills, Urinary irritation | BD Phoenix ID/AST Panel Inoculation System | Acute pyelonephritis | CEZ + GM → ABPC → AMPC for total 12 days | Complete resolution |

| 16 | Chan et al. [5] | 86 | Female | 2010 | Congestive heart failure, HT, Valvular heart disease, Parkinsonism, Dementia, Recent history of hospitalization | Hypotensive, Febrile, Tachycardiac, Tachypneic | BD Phoenix ID/AST Panel Inoculation System | Acute cholangitis | CMZ 16 days → oral antibiotics (unknown) total 23 days | Complete resolution |

| 17 | Talarmin et al. [7] | 78 | Female | 2011 | DM, HT, Aortic valve replacement with a bioprosthetic valve | Fever, Generalized weakness, Weight loss | I6S rRNA sequencing | Prosthetic valve endocarditis |

AMPC + GM 2 weeks → AMPC + RFP 4 weeks → relapse 4 months after discontinuation of antibiotics therapy, same antibiotics started as for the initial episode for total 6 weeks |

Relapse → Complete resolution |

| 18 | Sim et al. [20] | 61 | Male | 2012 | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis, DM | Abdominal pain, Fever, Chills, Generalized weakness | Automated MicroScan WalkAway system; sugar fermentation tests | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | CTX → VCM + CPFX → ABPC total 17 days | Complete resolution |

| 19 | Brulé et al. [18] | 44 | Male | 2013 | Alcoholic liver disease, Atrial fibrillation, Dilated cardiomyopathy | Fever, Diarrhea, Vomit | Gel electrophoresis | Bacteremia, Pyelonephritis |

CTRX + MNZ → add AMK → nephrectomy → AMPC total 21 days |

Complete resolution |

| 20 | Anghinah R et al. [10] | 56 | Male | 2013 | HT, DM, Hypercholesterolemia, Cardiac arrhythmia with surgical ablation, Surgical removal of a gastric leiomyoma | Slurred speech, Weight loss, Generalized fatigue, Depressive symptoms, Fever | Unknown | Native valve endocarditis |

Oxacillin + GM → ABPC → ABPC + RFP total 4 weeks + replacement of the aortic valve → RFP + AMPC 2 weeks |

Complete resolution |

| 21 | Alfouzan et al.[22] | 48 | Female | 2014 | DM | Abdominal pain, Productive cough, Fever | BD Phoenix Automated Microbiology System and DNA sequencing | Multiple splenic abscesses |

PIPC/TAZ + VCM + MNZ → Splenectomy → PIPC/TAZ + ABPC + LZD total 2 weeks |

Complete resolution |

| 22 | Dicpinigaitis et al. [27] | 85 | Female | 2015 | HT, Hyperlipidemia | Nausea, Vomit, Abdominal pain | MALDI-TOF MS | Acute Pancreatitis | PIPC/TAZ → CFPM → ABPC total 14 days | Complete resolution |

| 23 | Bourafa et a. [14] | 50 | Male | 2015 | BPH, DM, Urinary catheterization | Dysuria with cloudy urine, Suprapubic pain, Urinary frequency, and urgency | MALDI-TOF MS | Symptomatic lower UTI | APBC + GM total 10 days | Complete resolution |

| 24 | Paosinho et al. [3] | 78 | Female | 2016 | Atrial fibrillation, Chronic renal disease | Nausea, Lipothymia, Generalized weakness | Unknown | Acute pyelonephritis | AMPC/CVA → PIPC/TAZ total 14 days | Complete resolution |

| 25 | Atas et al. [21] | 70 | Female | 2017 | CKD, Dialysis | Abdominal pain, Cloudy dialysate | Unknown | Peritonitis | Intraperitoneal CXM-AX + CPFX PO → did not respond to therapy → VCM 3 weeks → discharge → relapse → Intraperitoneal VCM 3 weeks | Relapse → Complete resolution |

| 26 | Hee Lee et al. [4] | 78 | Male | 2017 | DM, HT, Coronary arterial occlusive disease | Left flank pain, Febrile sensation | BacT/ALERT 3D Microbial Detection System (bioMérieux Inc., Durham) | Acute Pyelonephritis | CTRX → CPFX po 14 days | Complete resolution |

| 27 | Hee Lee et al. [4] | 74 | Male | 2017 | DM, HT, Coronary arterial occlusive disease | Left flank pain, Febrile sensation, Chills | BacT/ALERT 3D Microbial Detection System (bioMérieux Inc., Durham) | Acute pyelonephritis | CTRX → CPFX po 14 days | Complete resolution |

| 28 | Gittemeier et al. [8] | 70 | Male | 2019 | N/A | Bilateral leg edema, Dyspnea on exertion, Fatigue | MALDI-TOF MS | Aortic valve endocarditis | VCM → ABPC + CTRX → Aortic valve replacement → CTRX + PCG total 6 weeks | Complete resolution |

| 29 | Merlo et al. [17] | 57 | Male | 2019 | DM, COPD, Hepatic cirrhosis Child–Pugh B secondary to HCV | Dyspnea, Disorientation, Fever | MALDI-TOF MS | Pneumonia | PIPC/TAZ + AZM + Rifaximine PO → AMPC/CVA total of 8 days | Complete resolution |

| 30 | Pinkes et al. [11] | 67 | Female | 2019 | COPD, Recurrent DVT, Atrial fibrillation, HT, Hypothyroidism, Hodgkin’s lymphoma | fever, hypotension, atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response, and a two-week history of lightheadedness | MALDI-TOF–MS | Native-valve endocarditis | Aortic valve replacement, ABPC + CTRX total of 6 weeks | Complete resolution |

| 31 | Brayer et al. [19] | 7 months | Male | 2019 | Gastroschisis, Jejunal atresia | Fussiness, Fever | Vitek 2 system (bioM.rieux) |

Catheter associated infection |

VCM + PIPC/TAZ → VCM → VCM + CTRX → ABPC + CTRX and for 2 weeks with synergistic GM |

Complete resolution |

| Our case | Nakamura et al. | 57 | Male | 2020 | Neurogenic bladder, Alcoholic cirrhosis | 3 days fever and chills | MALDI-TOF–MS | Acute pyelonephritis | CTRX → add ABPC → LZD PO | Complete resolution |

Vancomycin, VCM; tobramycin, TOB; flomoxef, FMOX; ampicillin, AMPC; gentamicin, GM; rifampin, RFP; PO, oral administration, Levofloxacin, LVFX; trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ST; Amoxicillin, AMPC; Ceftriaxone, CTRX; Ciprofloxacin, CPFX; Cefazolin, CEZ; Cefmetazole; CMZ, cefotaxime; CTX, metronidazole; MNZ, amikacin; AMK, piperacillin/tazobactam; PIPC/TAZ, linezolid; LZD, Cefepime, CFPM; benign prostatic hyperplasia, BPH; amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, AMPC/CVA; penicillin G, PCG; azithromycin, AZM, ESRD, end-stage renal disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HT, hypertension; cefuroxime axetil CXM-AX; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; deep vein thrombosis, DVT

In this review, one case of death due to biliary tract infection caused by E. hirae was reported [12]. The mortality rate (n = 1, 3%) from E. hirae infection was similar to or lower than that of other Enterococcus spp. infections (23%) [23]. However, the accumulation of E. hirae infections warrants accurate evaluation.

Three cases of E. hirae infection recurred during treatment [6, 7, 21], and two of the three recurrent cases involved infective endocarditis. In a report comparing 3308 cases of infective endocarditis caused by non-Enterococcus spp. with 516 cases of infective endocarditis caused by Enterococcus spp. collected prospectively from 35 centers in Spain, recurrence was significantly higher in cases of infective endocarditis caused by Enterococcus spp. (3.5% vs. 1.7%) [28]. There were nine reported cases of E. hirae urinary tract infections with no recurrences or deaths.

The susceptibility of E. hirae to antimicrobial agents is similar to that of E. faecalis, which is susceptible to penicillin. Table 3 shows the antimicrobial susceptibility of E. hirae infections in humans. Although some reports have reported high resistance to gentamicin [29], of the 21 antimicrobial-susceptible cases in this review, only four (19%) were gentamicin-resistant, and high-level gentamicin resistance cases were not reported. The relatively low mortality and antimicrobial resistance suggest that E. hirae is more similar to E. faecalis than E. faecium. In the present case, the patient could not tolerate ampicillin due to drug allergy and was successfully treated with linezolid after confirming susceptibility. Resistance to clindamycin and gentamicin has been reported repeatedly, and the possibility of resistance should be considered when these drugs are used. The accumulation of human clinical data is warranted to generate an accurate evaluation.

Table 3.

Summary of antimicrobial susceptibility in the previously reported human cases with Enterococcus hirae

| Case | Sensitive | Resistance | Supplement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ABPC, VCM, IPM GM | N/A | No beta-lactamase activity |

| 2 | N/A | N/A | |

| 3 | N/A | N/A | |

| 4 | ABPC, VCM, TEIC, CP | CLDM, EM, RFP, TC | Low-level resistance to SM, KM, GM |

| 5 | N/A | N/A | |

| 6 | N/A | N/A | |

| 7 | N/A | N/A | |

| 8 | N/A | N/A | |

| 9 | N/A | N/A | |

| 10 | ABPC, PCG, CP, CPFX, OFLX, LVFX, TC, VCM | CLDM, NFLX |

No evidence of high-level aminoglycoside resistance to GM or SM Intermediate susceptibility to EM, NTF |

| 11 | N/A | N/A | |

| 12 | N/A | N/A | |

| 13 | N/A | CLDM, Cephalosporins | |

| 14 | EM, CP, LZD, VCM | RFP | Intermediate susceptibility to ABPC, DOXY |

| 15 | ABPC, TEIC, VCM, high dose GM | OFLX, GM | |

| 16 | ABPC, TEIC, VCM, high dose GM | OFLX, GM | |

| 17 | ABPC, MFLX, VCM, TEIC, EM, RFP | CLDM, FOS | Low-level resistance to SM, KM, GM |

| 18 |

ABPC, VCM, TEIC, EM, TC high-level SM and GM |

N/A | |

| 19 | AMPC | Cephalosporins | |

| 20 | N/A | N/A | |

| 21 | ABPC, VCM, TEIC, LZD, TC | CPFX | No high-level resistance to GM |

| 22 | ABPC, VCM, CPFX | N/A | |

| 23 | high-level GM and KM, ABPC, LZD, CPFX, Nitrofuran, VCM | ST | |

| 24 | AMPC/CVA, PIPC/TAZ | CXM-AX, NTF | |

| 25 | VCM | N/A | |

| 26 | ABPC, ABPC/SBT, CPFX, EM, high-level GM, IPM, LVFX, LZD, NFLX, PCG, QPR/DPR, high-level SM, TEIC, TC, VCM, TGC | none | intermediate susceptibility to NTF |

| 27 | ABPC, ABPC/SBT, CPFX, EM, high-level GM, IPM, LVFX, LZD, NFLX, PCG, QPR/DPR, high-level SM, TEIC, TC, VCM, TGC | none | intermediate susceptibility to NTF |

| 28 | N/A | N/A | |

| 29 | ABPC, IPM, GM, CPFX, LVFX, VCM, TEIC, ST, LZD, TGC | N/A | |

| 30 | ABPC, AMPC, VCM | N/A | It demonstrated synergy with GM and SM |

| 31 | ABPC, VCM, high-level GM | N/A | |

| 32 | ABPC, PCG, VCM, LVFX, TEIC, LZD | none |

Ampicillin, ABPC; Vancomycin, VCM; Imipenem, IPM; Gentamicin, GM; Teicoplanin, TEIC; Chloramphenicol, CP; Clindamycin, CLDM; Erythromycin, EM; Rifampin, RFP; Streptomycin, SM; Kanamycin, KM; Penicillin G, PCG; CPFX, Ciprofloxacin; Levofloxacin, LVFX; Tetracycline; TC; Linezolid, LZD; doxycycline, DOXY; Moxifloxacin, MFLX; Amoxicillin, AMPC; Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, AMPC/CVA; Piperacillin/tazobactam, PIPC/TAZ; Ampicillin sulbactam, ABPC/SBT; trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ST; Cefuroxime axetil, CXM-AX; Norfloxacin, NFLX; Quinupristin/Dalfopristin, QPR/DPR; Fosfomycin, FOS; Tigecycline, TGC; Ofloxacin OFLX; Nitrofurantoin, NTF

Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was developed in the 1980s and was accurate in 80–95% of bacterial isolates [13]. Species-level identifications have been obtained and have been widely used in recent years [13]. A study validated the accuracy of MALDI-TOF MS for the identification of Enterococcus spp. compared with the gold standard rpoA gene sequencing method for the identification of bacteria of environmental origin. The occurrence of Enterococcus spp., including E. hirae, in wild birds was correctly identified by MALDI-TOF MS [30]. Before the advent of MALDI-TOF–MS, E. hirae may have been underdiagnosed because of the limitations of the diagnostic method [3]. This review found that there has been an increase in reporting of E. hirae since 2015 following the advent of MALDI-TOF MS.

Enterococcus hirae is a newly recognized causative pathogen of urinary tract infections, especially in patients with underlying diseases. Clinical data such as risk factors, clinical manifestations, and antimicrobial susceptibility are lacking, and more cases should be accumulated following accurate identification.

In summary, the number of E. hirae infections reported has increased following the development of MALDI-TOF MS. Although E. hirae may have a low virulence, as do other enterococci, clinicians need to consider E. hirae as a causative pathogen of urinary tract infection.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- E. hirae

Enterococcus hirae

- IV

Intravenous

- MALDI-TOF MS

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry

- WBC

White blood cell

Authors' contributions

The manuscript was seen and approved by all the authors and is not under consideration elsewhere. All the authors contributed to the work in this report. TN collected clinical data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. TN, KI, and FK performed the review of the literature. KI, TM, YU, and NM supervised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There were no sources of funding used in the conception, composition, editing, or submission of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Etheridge ME, Yolken RH, Vonderfecht SL. Enterococcus hirae implicated as a cause of diarrhea in suckling rats. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1741–1744. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1741-1744.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devriese LA, Haesebrouck F. Enterococcus hirae in different animal species. Vet Rec. 1991;129:391–392. doi: 10.1136/vr.129.17.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pãosinho A, Azevedo T, Alves JV, et al. Acute pyelonephritis with bacteremia caused by Enterococcus hirae: a rare infection in humans. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:4698462. doi: 10.1155/2016/4698462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee GH, Lee HW, Lee YJ, Park BS, Kim YW, Park S. Acute pyelonephritis with Enterococcus hirae and literature review. Urogenit Tract Infect. 2017;12:49–53. doi: 10.14777/uti.2017.12.1.49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan TS, Wu MS, Suk FM, et al. Enterococcus hirae-related acute pyelonephritis and cholangitis with bacteremia: an unusual infection in humans. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2012;28:111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poyart C, Lambert T, Morand P, Abassade P, Quesne G, Baudouy Y, et al. Nativevalve endocarditis due to Enterococcus hirae. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2689–2690. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2689-2690.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talarmin JP, Pineau S, Guillouzouic A, Boutoille D, Giraudeau C, Reynaud A, et al. Relapse of Enterococcus hirae prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1182–1184. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02049-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebeling CG, Romito BT. Aortic valve endocarditis from Enterococcus hirae infection. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2019;32:249–250. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2018.1551698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinh DC, Nichol KA, Rand F, Embil JM. Native-valve bacterial endocarditis caused by Lactococcus garvieae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;56:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anghinah R, Watanabe RG, Simabukuro MM, Guariglia C, Pinto LF, Gonçalves DC. Native valve endocarditis due to Enterococcus hirae presenting as a neurological deficit. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2013;2013:636070. doi: 10.1155/2013/636070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinkes ME, White C, Wong CS. Native-valve Enterococcus hirae endocarditis: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:891. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4532-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan CK, Lai CC, Wang JY, et al. Bacteremia caused by non-faecalis and non-faecium enterococcus species at a Medical center in Taiwan, 2000 to 2008. J Infect. 2010;61:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bizzini A, Greub G. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, a revolution in clinical microbial identification. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1614–1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourafa N, Loucif L, Boutefnouchet N, Rolain JM. Enterococcus hirae, an unusual pathogen in humans causing urinary tract infection in a patient with benign prostatic hyperplasia: first case report in Algeria. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;8:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) website. https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/

- 16.Farrow JA, Collins MD. Enterococcus hirae, a new species that includes amino acid assay strain NCDO 1258 and strains causing growth depression in young chickens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:73–75. doi: 10.1099/00207713-35-1-73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merlo J, Bustamante G, Llibre JM. Bacteremic pneumonia caused by Enterococcus hirae in a subject receiving regorafenib. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;38:226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brulé N, Corvec S, Villers D, Guitton C, Bretonnière C. Life-threatening bacteremia and pyonephrosis caused by Enterococcus hirae. Med Mal Infect. 2013;43:401–402. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brayer S, Linn A, Holt S, Ellery K, Mitchell S, Williams J. Enterococcus hirae bacteremia in an infant: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019;8:571–573. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piz028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sim JS, Kim HS, Oh KJ, Park MS, Jung EJ, Jung YJ, et al. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with sepsis caused by Enterococcus hirae. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:1598–1600. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.12.1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atas DB, Aykent B, Asicioglu E, Arikan H, Velioglu A, Tuglular S, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis with an unexpected micro-organism: Enterococcus hirae. Med Sci Int Med J. 2016;6:120–121. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfouzan W, Al-Sheridah S, Al-Jabban A, Dhar R, Al-Mutairi AR, Udo E. A case of multiple splenic abscesses due to Enterococcus hirae. JMM Case Rep. 2014;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billington EO, Phang SH, Gregson DB, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes for Enterococcus spp. blood stream infections: a population-based study. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;26:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilad J, Borer A, Riesenberg K, Peled N, Shnaider A, Schlaeffer F. Enterococcus hirae septicemia in a patient with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:576–577. doi: 10.1007/BF01708623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canalejo E, Ballesteros R, Cabezudo J, García-arata MI, Moreno J. Bacteraemic spondylodiscitis caused by Enterococcus hirae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:613–615. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolosi D, Nicolosi VM, Cappellani A, Nicoletti G, Blandino G. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of uncommon bacterial species causing severe infections in Italy. J Chemother. 2009;21:253–260. doi: 10.1179/joc.2009.21.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dicpinigaitis PV, de Aguirre M, Divito J. Enterococcus hirae Bacteremia associated with acute pancreatitis and septic shock. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2015;2015:123852. doi: 10.1155/2015/123852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pericàs JM, Llopis J, Muñoz P, et al. A contemporary picture of enterococcal endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mangan MW, McNamara EB, Smyth EG. Storrs MJ (1997) Molecular genetic analysis of high-level gentamicin resistance in Enterococcus hirae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:377–382. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stępień-pyśniak D, Hauschild T, Różański P, Marek A. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as a useful tool for identification of spp. from wild birds and differentiation of closely related species. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;27:1128–1137. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1612.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.