Abstract

BACKGROUND

One of the most common complications following surgery for midshaft clavicle fracture is nonunion/delayed union. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is an alternative to promote new bone formation without surgical complications. To date, no literature has reported low-intensity ESWT (LI-ESWT) in delayed union of midshaft clavicle fracture.

CASE SUMMARY

We reported a 66-year-old Chinese amateur cyclist with clavicle delayed union treated with 10 sessions of LI-ESWT (radial, 0.057 mJ/mm2, 3 Hz, 3000 shocks). No anesthetics were applied, and no side effects occurred. At the 4 mo and 7 mo follow-ups, the patient achieved clinical and radiographical recovery, respectively.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our findings indicated that LI-ESWT could be a good option for treating midshaft clavicular delayed union.

Keywords: Shockwave therapy, Clavicle fracture, Delayed union, Extracorporeal shock wave therapy, Case report

Core Tip: Clavicle fracture is a common injury for cyclists, and surgical intervention could result in nonunion or delayed union. This is the first case report in the literature of low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy treating midshaft clavicular delayed union. Our treatment protocol was unique in low-energy dosage, radial pattern, and multiple sessions. The clinical and radiographical outcomes were good, and the patient was able to return to sports, specifically amateur cycling, after a relatively short treatment period. The findings of this study could be particularly valuable for treating delayed union of clavicle fracture in athletes.

INTRODUCTION

Clavicle fractures, 80% of which occur at the midshaft, are the most common injury in cyclists, and studies have reported a prevalence of 13%-16% in this population vs 2.6%-4% in the general population[1-3]. With numerous studies indicating an unsatisfactory outcome and a high nonunion rate following conservative treatment, an increasing trend has been seen toward operative fixation of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures[4]. Nonunions and delayed unions are common complications of clavicle fracture operations. A complication rate of 15% was reported in revision surgery for clavicle nonunion[5]. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has emerged as a feasible alternative for treating delayed union. Compared with surgeries, ESWT has similar efficacy without surgical complications[6].

For bone healing, however, ESWT is mostly administered at middle-to-high energy (≥ 0.08 mJ/mm2) and in a focused pattern[7,8]. However, the clavicle is currently considered unsuitable for conventional ESWT due to its superficial anatomical site and proximity to the air-filled lung tissue, which creates large differences in acoustic impedance and offers considerable risks of lung injury[9]. To the best of our knowledge, no clinical literature has reported the use of low-intensity ESWT (LI-ESWT) in delayed union of clavicle fracture after internal fixation. Here, we present a case of delayed union of the clavicle in a cyclist after screw and plate fixation. After 10 sessions of LI-ESWT treatment at an outpatient clinic, the patient achieved a satisfying asymptomatic recovery and bone union as indicated by radiographs during follow-ups. Informed consent was obtained from the patient, and this study was approved by our ethics committee of our hospital (No. 2020-340).

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 66-year-old male Chinese amateur cyclist visited the clinic for consistent right collarbone site pain [visual analog scale (VAS) = 40 mm in static and 60 mm in active] and limited range of motion in the right upper arm.

History of present illness

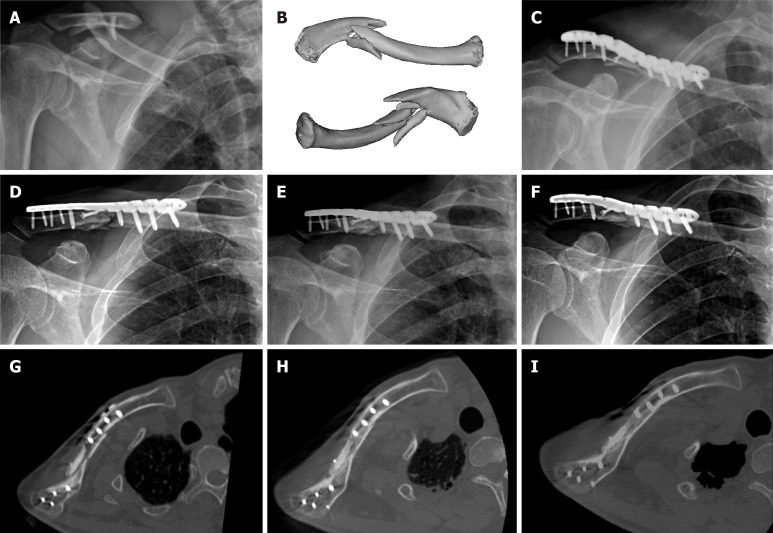

He had become injured during bicycle training 3 mo prior to this clinic visit, and emergency imaging showed comminuted midshaft clavicle fracture with complete displacement. He then underwent open reduction and internal fixation in our center (Figure 1A-C).

Figure 1.

Imaging examinations. A: Anteroposterior X-ray image of the initial injury; B: Three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) reconstruction images of the initial injury; C: Anteroposterior X-ray image after the internal fixation surgery; D: Anteroposterior X-ray image 3 mo postoperatively; E: Anteroposterior X-ray image 4 mo after shockwave therapy; F: Anteroposterior X-ray image 7 mo after shockwave therapy; G: CT scan image 3 mo postoperatively; H: CT scan image 4 mo after shockwave therapy; I: CT scan image 7 mo after shockwave therapy.

History of past illness

The patient had a 30-year history of smoking with a minimum of 10 cigarettes per day. He had no other relevant medical history.

Personal and family history

There was no special personal or family history.

Physical examination

A horizontal surgical scar and local tenderness were noticed on his right clavicle site. No sign of infection was noticed. Pain could be aggravated by abduction and extension of the right upper arm. His Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) functional score was 43 when measured in the clinic.

Imaging examinations

Plain radiographs showed correct instrument position but cortical discontinuity of the midshaft. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed discontinuity of the cortex, no sign of bridging callus, and trabecular bone with a nonunion gap of 3 mm (Figure 1D and G).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Delayed union of midshaft clavicle fracture.

TREATMENT

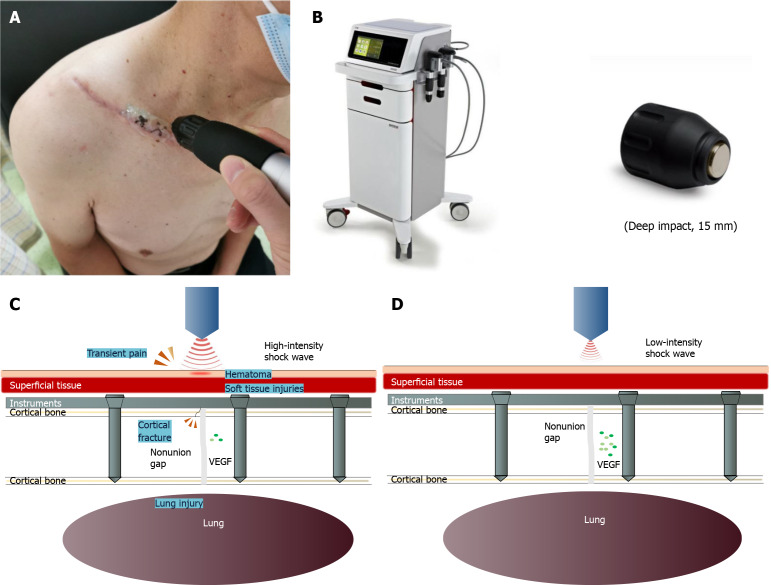

We used the shock wave device ShockMaster 500 (GymnaUniphy NV, Bilzen, Belgium) for treatment. LI-ESWT treatment utilized ultrasound-assisted localization, and local anesthesia was not required (Figure 2A and B). The patient received a total of 10 sessions with a 2-d interval between two sessions, and each session lasted for approximately 10 min. The therapeutic parameter was 0.057 mJ/mm2, radial pattern, 3 Hz and 3000 strikes. No immobilization was required after any treatment.

Figure 2.

Illustration diagram of the treatment process, equipment and mechanism of low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy for clavicle nonunion. A: Treatment of the current patient by a therapist without anesthetics; B: Illustration of shockwave device and applicator; C: Mechanism diagram of the potential risks of conventional shockwave treatment for clavicle nonunion; D: Mechanism diagram of superiority of low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy treatment for clavicle nonunion. VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

At the 4-mo follow-up, the patient’s VAS was 0 mm in active and 10 mm in static, while the DASH scores of the patient decreased to 7. At the 7-mo follow-up, both the VAS and DASH scores of the patient had decreased to 0. The patient’s global assessment at the 7-mo follow-up was “much better.” During the whole follow-up process, the patient experienced no therapy-related complications.

Bridging callus and new bone formation on X-ray and CT were observed at the 4 mo follow-up and further enhanced at the 7 mo follow-up (Figure 1D-I). The patient was able to attend normal cycling training on his last visit, but doctors suggested that he avoid intensive exercise.

DISCUSSION

Delayed union of fracture is mostly defined as no signs of bone healing 3-6 mo after injury or operation on X-ray or CT scan[10,11]. The incidence of clavicle nonunion can be as high as 7.5% for operational treatment, and surgery to revise clavicle nonunion can have an even higher complication rate than the initial surgery[5]. Risk factors for nonhealing midshaft clavicle fractures are smoking, complexity of fracture, complete fracture displacement, advanced age, and female sex. Displacement seems to be the most likely factor[12]. The risk factors for the current patient, as he was informed before surgery, were complete dislocation of the initial fracture, smoking habit, and age. High-energy ESWT, since the first report of its application in bone nonunion by Valchanou et al[13] in 1991, has been proven to be as effective as surgical procedures but free of surgical side effects for the treatment of ununited fractures. To date, both guidelines and the literature have mostly applied middle-to-high-energy ESWT to treat nonunion[10,14-16]. Shockwave-promoted bone healing is associated with mechanically induced microfractures, periosteal detachment, and a complex spectrum of biomolecular reactions[17,18]. However, high-energy ESWT can have hazardous effects, such as soft tissue edema, cortical fractures, intraosseous bleeding, and even displacement of bone fragments to pulmonary vessels, with the risk of pulmonary embolism[19]. Similar cambium cell proliferation was seen in low energy flux density (EFD) compared with a high-energy setting, and shockwaves with lower EFD have more capacity to induce angiogenesis and improve tissue perfusion in target tissues through upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor[20,21] (Figure 2C and D).

In superficial musculoskeletal disorders, LI-ESWT has proven to be more therapeutic in pain relief than high-energy ESWT[22]. Tam et al[23] suggested that low-intensity treatment with more shocks under the same total energy dose (intensity multiplied by number of shocks) was more favorable in enchaining periosteal cell activities. The study by Ke et al[24] showed that multiple sessions of ESWT had greater efficacy than single sessions from the perspective of the clinically cumulative effect. It should be noted that ESWT treatment for clavicle fracture is potentially risky for lung tissue damage, as suggested in animal experiments[25,26]. Moreover, high-intensity ESWT is often more costly and more likely to be performed in an inpatient setting, whereas LI-ESWT can be performed at an outpatient clinic by a therapist[27].

The criteria of LI-ESWT vary. Here, we defined ESWT as EFD < 0.08 mJ/mm2, as in previous reports[27]. Five studies to date reported ESWT on delayed clavicle union or nonunion. Alkhawashki[28] reported one case of successful ESWT treatment of clavicle nonunion, but the treatment was high-energy ESWT conducted in a single session. Moretti et al[29] reported ESWT treatment of clavicle pseudoarthrosis with EFD of 0.22-1.10 mJ/mm2. Kertzman et al[7] reported a failed case of radial ESWT treatment of a clavicle nonunion despite initial surgical fixation with two sessions of 0.18 mJ/mm2 treatment. Vulpiani et al[30] and Carfagni et al[31] also reported clavicle nonunion treated with middle-to-high-energy ESWT, but the methods or results were not individually shown (Table 1). None of these studies mentioned side effects. We learned from these studies and used a lower dose administered over more sessions for our patient, which produced positive results with no side effects.

Table 1.

Literature review and summary of extracorporeal shock wave therapy treatment of clavicle nonunion/delayed union/pseudoarthrosis (to April 6, 2021)

|

Ref.

|

Study type

|

Clavicle cases/total cases

|

Initial fracture treatment

|

Device

|

Energy level

|

Sessions

|

Outcome

|

| Moretti et al[29], 2009 | Retrospective case series | NM/204 | NM | Minilith SL1 (Storz) | 0.22-1.10 mJ/mm2 | NM | Positive |

| Carfagni et al[31], 2011 | Retrospective case series | 3/93 | NM | Duolith (Storz), Modulith SLK (Storz) | 0.20-0.55 mJ/mm2 | 4-5 | NM |

| Vulpiani et al[30], 2012 | Prospective cohort study | 6/143 | Conservative treatment and Internal fixation | Modulith SLK (Storz) | 0.25-0.84 mJ/mm2 | 3-5 | NM |

| Alkhawashki[28], 2015 | Retrospective case series | 1/49 | Conservative treatment | OssaTron (HMT) | 26 KV | 1 | Positive |

| Kertzman et al[7], 2017 | Retrospective case series | 1/22 | Internal fixation | Swiss DolorClast (EMS) | 0.18 mJ/mm2 | 2 | Negative |

NM: Not mentioned.

However, this was only a pilot study. Studies with a higher level of evidence must be conducted to verify our findings.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this report describes a novel LI-ESWT protocol to optimize the clinical efficacy for delayed union of clavicle fracture that had been treated with internal fixation. The findings of this study could be particularly useful for dealing with delayed union or nonunion of midshaft clavicle fractures.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying imaging.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: May 4, 2021

First decision: June 24, 2021

Article in press: August 3, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kung WM, Ng BW, Yukata K S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LYT

Contributor Information

Lei Yue, Department of Orthopaedics, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China.

Hao Chen, Department of Rehabilitation, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China.

Tian-Hao Feng, Department of Orthopaedics, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China.

Rui Wang, Department of Orthopaedics, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China.

Hao-Lin Sun, Department of Orthopaedics, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China. sunhaolin@vip.163.com.

References

- 1.Khan LA, Bradnock TJ, Scott C, Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:447–460. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Ven DJC, Timmers TK, Broeders IAMJ, van Olden GDJ. Displaced Clavicle Fractures in Cyclists: Return to Athletic Activity After Anteroinferior Plate Fixation. Clin J Sport Med. 2019;29:465–469. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishimi AY, Belangero PS, Mesquita RS, Andreoli CV, Pochini AC, Ejnisman B. Frequency and risk factors of clavicle fractures in professional cyclists. Acta Ortop Bras. 2016;24:240–242. doi: 10.1590/1413-785220162405157391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson GA, Wood AM, Oliver CW. Displaced middle-third clavicle fracture management in sport: still a challenge in 2018. Should you call the surgeon to speed return to play? Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:348–349. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ban I, Troelsen A. Risk profile of patients developing nonunion of the clavicle and outcome of treatment--analysis of fifty five nonunions in seven hundred and twenty nine consecutive fractures. Int Orthop. 2016;40:587–593. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zelle BA, Gollwitzer H, Zlowodzki M, Bühren V. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy: current evidence. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24 Suppl 1:S66–S70. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181cad510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kertzman P, Császár NBM, Furia JP, Schmitz C. Radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy is efficient and safe in the treatment of fracture nonunions of superficial bones: a retrospective case series. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12:164. doi: 10.1186/s13018-017-0667-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gebauer D, Mayr E, Orthner E, Ryaby JP. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound: effects on nonunions. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:1391–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eroglu M, Cimentepe E, Demirag F, Unsal E, Unsal A. The effects of shock waves on lung tissue in acute period: an in vivo study. Urol Res. 2007;35:155–160. doi: 10.1007/s00240-007-0092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The International Society for Medical Shockwave Treatment. DIGEST Guidelines for Extracorporeal Shock wave Therapy. 2019. [cited 3 May 2021]. Available from: https://wwwshockwavetherapyorg/about-eswt/ismst-guidelines/

- 11.Nicholson JA, Fox B, Dhir R, Simpson A, Robinson CM. The accuracy of computed tomography for clavicle non-union evaluation. Shoulder Elbow. 2021;13:195–204. doi: 10.1177/1758573219884067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jørgensen A, Troelsen A, Ban I. Predictors associated with nonunion and symptomatic malunion following non-operative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures--a systematic review of the literature. Int Orthop. 2014;38:2543–2549. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valchanou VD, Michailov P. High energy shock waves in the treatment of delayed and nonunion of fractures. Int Orthop. 1991;15:181–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00192289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cacchio A, Giordano L, Colafarina O, Rompe JD, Tavernese E, Ioppolo F, Flamini S, Spacca G, Santilli V. Extracorporeal shock-wave therapy compared with surgery for hypertrophic long-bone nonunions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2589–2597. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biedermann R, Martin A, Handle G, Auckenthaler T, Bach C, Krismer M. Extracorporeal shock waves in the treatment of nonunions. J Trauma. 2003;54:936–942. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000042155.26936.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaden W, Mittermayr R, Haffner N, Smolen D, Gerdesmeyer L, Wang CJ. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT)--First choice treatment of fracture non-unions? Int J Surg. 2015;24:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haffner N, Antonic V, Smolen D, Slezak P, Schaden W, Mittermayr R, Stojadinovic A. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) ameliorates healing of tibial fracture non-union unresponsive to conventional therapy. Injury. 2016;47:1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yip HK, Chang LT, Sun CK, Youssef AA, Sheu JJ, Wang CJ. Shock wave therapy applied to rat bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells enhances formation of cells stained positive for CD31 and vascular endothelial growth factor. Circ J. 2008;72:150–156. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maier M, Hausdorf J, Tischer T, Milz S, Weiler C, Refior HJ, Schmitz C. [New bone formation by extracorporeal shock waves. Dependence of induction on energy flux density] Orthopade. 2004;33:1401–1410. doi: 10.1007/s00132-004-0734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kearney CJ, Lee JY, Padera RF, Hsu HP, Spector M. Extracorporeal shock wave-induced proliferation of periosteal cells. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1536–1543. doi: 10.1002/jor.21346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang HJ, Cheng JH, Chuang YC. Potential applications of low-energy shock waves in functional urology. Int J Urol. 2017;24:573–581. doi: 10.1111/iju.13403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taheri P, Emadi M, Poorghasemian J. Comparison the Effect of Extra Corporeal Shockwave Therapy with Low Dosage Versus High Dosage in Treatment of the Patients with Lateral Epicondylitis. Adv Biomed Res. 2017;6:61. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.207148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tam KF, Cheung WH, Lee KM, Qin L, Leung KS. Delayed stimulatory effect of low-intensity shockwaves on human periosteal cells. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438:260–265. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200509000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ke MJ, Chen LC, Chou YC, Li TY, Chu HY, Tsai CK, Wu YT. The dose-dependent efficiency of radial shock wave therapy for patients with carpal tunnel syndrome: a prospective, randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38344. doi: 10.1038/srep38344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delius M, Enders G, Heine G, Stark J, Remberger K, Brendel W. Biological effects of shock waves: lung hemorrhage by shock waves in dogs--pressure dependence. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1987;13:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(87)90075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong C, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Cong P, Shi X, Shi Hongxu Jin L, Hou M. Shock waves increase pulmonary vascular leakage, inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in a mouse model. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2018;243:934–944. doi: 10.1177/1535370218784539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verstraelen FU, In den Kleef NJ, Jansen L, Morrenhof JW. High-energy vs low-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy for calcifying tendinitis of the shoulder: which is superior? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2816–2825. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3680-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alkhawashki HM. Shock wave therapy of fracture nonunion. Injury. 2015;46:2248–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moretti B, Notarnicola A, Moretti L, Patella S, Tatò I, Patella V. Bone healing induced by ESWT. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2009;6:155–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vulpiani MC, Vetrano M, Conforti F, Minutolo L, Trischitta D, Furia JP, Ferretti A. Effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on fracture nonunions. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2012;41:E122–E127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carfagni A, D’Innella G, Bagozzi C. Delayed unions/nonunions: Treatment with shock waves. J Orthop Traumatol . 2011;12:S101. [Google Scholar]