Abstract

Objective:

Efavirenz (EFV) use is associated with neuropsychiatric side effects, which may include poor neurocognitive performance. We evaluated single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes that contribute to EFV pharmacokinetics and examined them in association with EFV concentrations in plasma and hair, as well as neurocognitive performance.

Design:

Cross-sectional study in which adults with HIV receiving 600-mg EFV for at least 2 months were recruited and paired hair and dried blood spots (DBS) samples collected.

Methods:

Participants (N = 93, 70.3% female) were genotyped for seven single nucleotide polymorphisms in CYP2B6, NRII3 and ABCB1 using DBS. EFV was quantified in DBS and hair using validated liquid-chromatography–tandem-mass-spectrometry methods, with plasma EFV concentrations derived from DBS levels. Participants were also administered a neurocognitive battery of 10 tests (seven domains) that assessed total neurocognitive functioning.

Results:

Strong correlation (r = 0.66, P < 0.001) was observed between plasma and hair EFV concentrations. The median (interquartile range) hair EFV concentration was 6.85 ng/mg (4.56–10.93). CYP2B6 516G>T, (P < 0.001) and CYP2B6 983T>C (P = 0.001) were each associated with hair EFV concentrations. Similarly, 516G>T (P < 0.001) and 983T>C (P = 0.009) were significantly associated with plasma EFV concentration. No other genetic associations were observed. Contrary to other studies, total neurocognitive performance was significantly associated with plasma EFV concentrations (r = 0.23, P = 0.043) and 983T>C genotype (r = 0.38, P < 0.0005).

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated approximately three-fold and two-fold higher EFV plasma and hair concentrations, respectively, among CYP2B6 516TT compared with 516GG. Higher EFV concentrations were associated with better neurocognitive performance, requiring further study to elucidate the relationships between adherence, adverse effects and outcomes.

Keywords: dried blood spots, efavirenz, hair, neurocognitive performance, single nucleotide polymorphisms

Introduction

Efavirenz (EFV) is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor widely used for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in combination antiretroviral therapy (ART). EFV has a long half-life which allows for once daily dosing. This antiretroviral is currently recommended as a component of alternative first-line regimens for HIV treatment by the WHO [1]. The second-generation integrase inhibitor, dolutegravir (DTG), replaced EFV in the latest WHO update for first-line ART given that DTG-based therapy is better tolerated, virologically non-inferior, and has a higher genetic barrier to resistance than EFV-based regimens [2]. Nevertheless, EFV is still widely used in sub-Saharan Africa (including Nigeria) because of its effectiveness and relatively low cost. Fixed-dose EFV-based regimens are suitable across populations, including for patients on rifampicin-containing anti-tuberculosis drugs, whereas DTG has to be increased to twice daily if co-administered with rifampicin [1].

EFV is metabolized mainly by CYP2B6 to 8-hydroxy-EFV as the primary metabolite. CYP2B6 has been extensively studied in relationship to EFV and certain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of CYP2B6 have been reported to influence EFV concentrations in plasma and hair [3–5]. CYP2B6 516G>T and CYP2B6 983T>C, known as decreased function and no function alleles, respectively [6], are consistently associated with increased concentrations of EFV in both hair and plasma. EFV concentration in hair and plasma were three-fold higher in individuals with homozygosity in CPY2B6 516T compared with CPY2B6 516GT and CPY2B6 516GG[3,5].

Despite the efficacy of EFV, the drug can have treatment-limiting central nervous system (CNS) toxicities [4,7,8]. CNS toxicity impacts negatively on patients’ quality of life, as well as adherence to ART. Some studies have linked EFV CNS side effects, as well as treatment discontinuation, to high plasma concentrations of EFV, [4,8,9] as well as certain SNPs in CYP2B6. These studies evaluated short-term effects of EFV. However, there are limited data on the long-term impact of EFV on neurocognitive performance to date.

The relationship between EFV use and neurocognitive function is complicated. Generally, neurocognitive performance tends to improve with ART initiation [10,11]. In contrast, long-term exposure to EFV has been linked to worse neurocognitive performance in people living with HIV (PWH) [12]. However, other data on the long-term impact of EFV on neuropsychological performance showed improvement in neuropsychological performance compared with data collected at baseline [13]. This data did not measure long-term EFV exposure (e.g. EFV concentrations in hair) which may show a different relationship with neurocognitive performance than use of EFV concentration in plasma (a short-term metric) alone.

In this study, we evaluated SNPs in genes important for EFV disposition and examined them in association with plasma and hair concentrations of EFV. We further evaluated the relationship between EFV levels and neurocognitive performance, to address these known gaps in the literature.

Methods

Participant recruitment

Persons with HIV who were attending Infectious Disease Institute, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan and were receiving 600-mg EFV once daily as part of their ART regimen for at least 2 months were eligible. Potential participants were interviewed to ascertain willingness to donate hair and blood. Consenting participants were enrolled from July 2017 to November 2017. Each participant provided the time of their last ART dose before samples were collected. Participants who reported missing their drugs for 2 days or more before sample collection, or were pregnant, were excluded from the study. Participants who did not pick up their ART as prescribed from the clinic pharmacy were excluded from analysis. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study. The study was approved by the Joint University of Ibadan/UCH Research Ethics Committee.

Sample collection and analysis

Single point paired dried blood spots (DBS) and hair samples were collected from participants at mid-dose interval up to 17 h post dose. In addition, each participants’ hematocrit was determined for standardization of DBS values. Participants were also administered a battery of 10 neurocognitive tests (seven domains) that assessed total neurocognitive functioning. Other patient characteristics were extracted from medical records.

Dried blood spots sample collection and measurement of efavirenz

Whole venous blood (about 1 ml) was collected in lithium heparinized tubes from each participant and five 50 μl spots were made onto two separate Whatmann 903 protein saver cards for both DNA extraction and measurement of EFV. The spotted cards were left at room temperature (RT) on the laboratory bench to dry for about 24 h. Then, each card was placed inside a separate Ziploc bag with two bags of desiccant and one humidity indicator card and sealed tightly. The samples for the EFV assay were stored at −20 oC until shipment to the Pharmacology and Therapeutics Laboratory, University of Liverpool, UK by courier for analysis.

EFV concentrations in DBS were measured using validated liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)-based methods as previously described [14]. The lower and upper limits of quantification were 0.025 and 5 μg/ml, respectively. Plasma EFV concentration was derived from the DBS concentration using a previously validated equation [DBS[EFV]/(1−hematocrit)×protein binding] [15]. In this equation, hematocrit is the patient-specific hematocrit and protein binding represents the fraction of EFV (0.995) bound to plasma protein while DBS[EFV] is the concentration of EFV in DBS. Plasma EFV concentrations were classified into three categories considered to be therapeutically important [8].

Hair sample collection and measurement of efavirenz

A small thatch of hair (20–30 strands) was cut as close as possible to the scalp from each participant [5]. The hair samples were stored at RT until shipped to the Hair Analytical Laboratory (HAL) at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), USA for analysis.

In the laboratory, each hair sample was cut down to 1.5 cm in length from the root (to reflect the past ∼6 weeks of exposure). The extraction of EFV and quantification in hair were achieved using previously described and validated LC–MS/MS-based methods [16]. The lower and upper limits of quantifications are 0.05 and 20 ng/mg, respectively. Details of this procedure has been described elsewhere [16] and the UCSF HAL's methods for analyzing EFV in hair have been peer reviewed and approved by the NIH's Clinical Pharmacology and Quality Assurance program [17].

DNA extraction and genotyping

The E.Z.N.A DNA extraction kit was used to extract genomic DNA from DBS according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantification of the extracted DNA was performed using NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer and the DNA was stored at −20 oC. SNP genotyping was performed using real-time PCR (DNA Engine Chromo4 System; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, California, USA). Allelic discrimination plots were obtained using opticon monitor software version 3.1. Allelic discrimination reactions were performed using TaqMan assays obtained from Life Technologies Ltd (Paisley, Renfrewshire, UK). The TaqMan SNP genotyping assays for the seven SNPs genotyped included; C_7817765_60 for CYP2B6516G>T (rs3745274), C_60732328_20 for CYP2B6983T>C (rs28399499), C_16194070_10 for NR1I3c.152–1089T>C (rs3003596), C_25746794_20 for NR1I3 c.540C>T (rs2307424), C_7586662_10 for ABCB11236C>T (rs1128503), C_11711730_20 for ABCB14036A>G (rs3842) and C_7586657_20 for ABCB1 3435A>G (rs1045642). The PCR amplification was achieved under the following conditions: an initial denaturation step at a temperature of 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 50 cycles of amplification at 95 °C for 15 s and a final annealing at 60 °C for 1 min.

Neurocognitive assessments

Trained personnel administered the neuropsychological examination. Participants were administered a neurocognitive battery that assessed total neurocognitive functioning in the domains of fluency, attention, learning, memory, fine motor, speed of processing and executive functioning. The test infrastructure used has been previously used in diverse resource limited settings and the normative data used for data comparison was from International Neurocognitive Normative Study (INNS) (ACTG A5271) [18]. The neuropsychological test scores were transformed into z-scores using the normative data from the INNS. Details of the standardized neurological and neuropsychological method has been described elsewhere [18,19]. Total z-scores were obtained from the collected data and were used to determine the correlation between EFV concentrations in plasma and hair with neurocognitive performance.

Statistical analysis

Allele and genotype frequency compliance to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was tested using the Chi-square test. Normality of continuous variables were tested using Histogram plots, Q–Q plots and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Mean (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)] were used to summarize continuous variables while categorical variables were summarized by frequency in a descriptive analysis. Correlations between continuous variables were tested using Pearson or Spearman Correlations. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to ascertain differences in median EFV concentrations by genotype. To achieve normal distributions for EFV concentrations, hair and plasma concentrations were log10 transformed. Independent t test was used to assess differences in mean total z-scores between male and female. Covariate effects on log10 transformed plasma or hair concentrations of EFV were ascertained using univariate linear regression. Independent variables with P value of 0.1 or less in the univariate linear regression models were included in a stepwise multiple regression model. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics version 25 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, California, USA).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Of the 93 participants who gave hair and DBS samples, two individuals were excluded from the analysis because clinic pharmacy records revealed that they had not picked up their ART for at least 3 months prior to sample collection. The mean (SD) age of participants was 44.5 ± 11.22 years. Other participants’ characteristics has been summarized (Table 1). Genotype frequencies for the studied population are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and other characteristics of the participants (n = 91).

| Characteristics | N (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 27 (29.7) | ||

| Female | 64 (70.3) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Yoruba | 79 (86.8) | ||

| Hausa | (4.4) | ||

| Igbo | 3 (3.3) | ||

| Other | 5 (5.5) | ||

| Backbone antiretroviral | |||

| TDF/3TC | 84 (92.3) | ||

| ABC/3TC | 5 (5.5) | ||

| TDF/FTC | 2 (2.2) | ||

| Age (years) | 44.5 (11.22) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 63 (64–73) | ||

| No of months on EFV | 45 (23.5–70.0) | ||

| Time post dose (h) | 14.7 (13.5–16) | ||

| Hematocrit (%) | |||

| Male | 38.2 (6.98) | ||

| Female | 36 (33–37.5) | ||

| Baseline viral load (copies/ml) | 63 493 (12 429–173 214) | ||

| Latest viral load | 10 (10–26) | ||

| Baseline CD4+ cell count (cells/μl) | 241 (131.0–362.8) | ||

| Latest CD4+ cell count | 445 (274–600) | ||

EFV, efavirenz; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2.

Allele and genotype frequencies.

| SNP | Allele and genotype frequencies | ||||

| CYP2B6 516G>T | GG: 0.366 | GT: 0.495 | TT: 0.14 | G: 0.613 | T: 0.387 |

| CYP2B6 983T>C | TT: 0.828 | CT: 0.172 | CC: 0.000 | T: 0.914 | C: 0.086 |

| NR1I3c.152–1089T>C | TT: 0.194 | CT: 0.473 | CC: 0.333 | T: 0.43 | C: 0.57 |

| NR1I3 c.540C>T | CC: 0.839 | CT: 0.14 | TT: 0.022 | C: 0.909 | T: 0.091 |

| ABCB1 1236C>T | CC: 0.731 | CT: 0.258 | TT: 0.011 | C: 0.860 | T: 0.140 |

| ABCB1 4036A>G | AA: 0.763 | AG: 0.215 | GG: 0.022 | A: 0.871 | G: 0.129 |

| ABCB1 3435A>G | GG: 0.817 | AG: 0.172 | AA: 0.011 | A: 0.097 | G: 0.903 |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

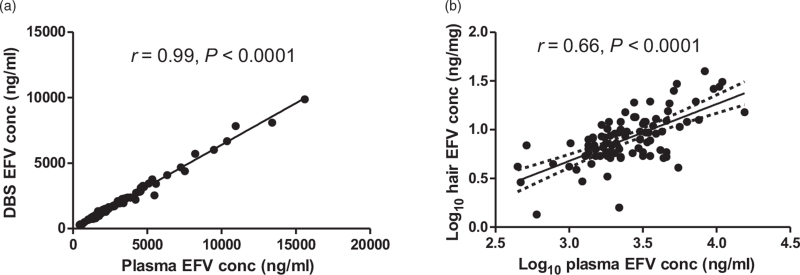

Efavirenz concentrations in plasma

There was a strong correlation between EFV concentration in DBS and the DBS-derived plasma concentrations (r = 0.99, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1a). However, EFV concentration in DBS was about 33% lower than derived-plasma values. The median (IQR) EFV plasma concentration was 2237 ng/ml (1655–3858). There was wide variability in plasma EFV concentrations among the population studied, with concentrations ranging from 446.821 to 15 592.334 ng/ml. Classifying plasma concentrations into three categories considered to be therapeutically important, 5.5% (n = 5), 71.4% (n = 65) and 23.1% (n = 2), of 91 participants had plasma concentrations less than 1000 ng/ml (subtherapeutic), 1000–4000 ng/ml (therapeutic) and greater than 4000 ng/ml (supratherapeutic), respectively.

Fig. 1.

(a) Correlations between efavirenz concentrations in DBS and plasma. (b) Log10 transformed efavirenz concentrations in hair and plasma. Pearson r = 0.66 (0.53, 0.77).

Solid line represents mean value and the broken lines represent 95% confidence interval.

Efavirenz concentrations in hair

EFV concentration was measured from 91 hair samples (one per participant). However, one measurement was excluded from the analysis after failing quality control procedures in the laboratory. The median IQR EFV hair concentration was 6.85 ng/mg (4.56–10.93). There was a strong correlation between the log transformed plasma EFV concentration and EFV concentrations in hair (Pearson's correlation, r = 0.66; P < 0.001) (Fig. 1b).

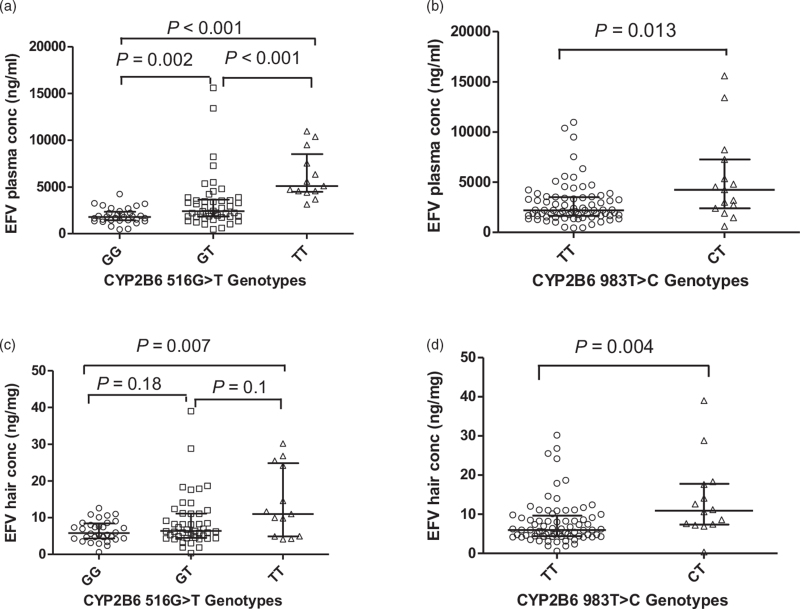

Factors associated with efavirenz concentrations in plasma

Age, sex, ethnicity, time post dose, and number of months on EFV did not show significant associations with plasma EFV concentrations in a simple linear regression, but a trend was demonstrated in which lower weight was associated with higher plasma EFV concentrations (P = 0.09). Of the seven SNPs assessed, only CYP2B6 516G>T and CYP2B6 983T>C were significantly associated with log10 plasma concentrations of EFV with P less than 0.001 and P = 0.009, respectively. There were significant differences in plasma EFV concentrations based on CYP2B6 516G>T and CYP2B6 983T>C (Fig. 2a and Table 3). Median EFV plasma concentrations were lower for participants with 983TT compared with 983TC (Fig. 2b and Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of efavirenz concentrations in hair and plasma versus CYP2B6 genotype. (a) EFV plasma concentrations vs CYP2B6516G>T genotype. (b)EFV plasma concentrations vs CYP2B6983T>C genotype. (c) EFV hair concentrations vs CYP2B6516G>T genotype. (d) EFV hair concentrations vs CYP2B6983T>C genotype.

Table 3.

Dried blood spots-derived plasma efavirenz concentrations and total z-scores stratified based on two single nucleotide polymorphisms in CYP2B6.

| SNP | Genotype | Median (IQR) DBS-derived plasma concentrations (ng/ml) | Median (IQR) hair concentration in ng/mg |

| CYP2B6 516 G>T | GG | 1790 (1423.59–2341.31) | 5.80 (4.34–8.45) |

| GT | 2410 (1817.30–3634.74) | 6.38 (4.61–11.15) | |

| TT | 5094 (4480.93–8506.28) | 11.0 (4.91–24.85) | |

| CYP2B6 983 T>C | TT | 2198.44 (1637.27–3501.38) | 5.97 (4.41–9.64) |

| CT | 4244.45 (2383.87–7264.50) | 10.90 (7.37–17.77) |

DBS, dried blood spots; IQR, interquartile range; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Factors associated with efavirenz concentrations in hair

Similar to the associations seen with plasma EFV concentrations, CYP2B6 516G>T and CYP2B6 983T>C showed significant associations with hair EFV concentrations, P less than 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively. There were approximately two-fold higher median hair concentrations in CYP2B6516T homozygote participants compared with CYP2B6516G homozygote participants. No other genetic (NR1I3 c.152–1089T>C, NR1I3 c.540C>T, ABCB11236C>T, ABCB14036A>G or ABCB13435A>G) or demographic (age, sex, ethnicity, weight) associations with hair levels were evident. The median (IQR) hair EFV concentration was 6.85 ng/mg (4.56–10.93). The median (IQR) hair concentrations stratified by genotypes is shown in Table 3. There was a significant difference in median hair EFV concentrations for CYP2B6516GG and CYP2B6516TT (P = 0.007) (Fig. 2c). Similarly, the difference in median hair EFV concentrations between CYP2B6 983TT and CYP2B6 983TC was significant (P = 0.004) (Fig. 2d).

Neurocognitive performance and efavirenz concentrations

Out of the 91 participants who had plasma EFV concentrations, ten participants were excluded from analysis because their data revealed that they could not speak the English language which is required to complete this neurocognitive performance test. The mean (SD) total z-score of the neurocognitive assessments for the remaining 81 participants was 0.002 (0.29) (Table 3); a more positive z-score value indicates better neurocognitive performance. The mean (SD) total z-scores of males and females were 0.1 (0.3) and −0.03 (0.3), respectively, with men demonstrating better performance (P = 0.03, confidence interval, −0.27, −0.01). A significant positive relationship was found between neurocognitive performance and EFV plasma concentrations (r = 0.23, P = 0.043). This was mostly seen in the domains of executive functioning, with trends in fine motor skills and speed of processing.

Discussion

The article evaluates for the first time the association between concentrations of EFV in two biomatrices, polymorphisms in genes associated with EFV metabolism, and neurocognitive function in a cohort of PWH in Nigeria. Short-term and long-term EFV exposure were determined in DBS and hair samples, respectively. Moreover, hair sample collection was highly successful in this Nigerian cohort (100% acceptability) despite beliefs in this setting that a person's hair can be used for ritual purposes [20]. We showed significant association between EFV metabolism in CYP2B6 and concentrations of the drug in both plasma and hair.

Our study is the first to measure antiretroviral drug levels in hair in Nigeria. DBS represents a suitable alternative for measuring short-term antiretroviral drug levels in resource-constrained settings, offering advantages over plasma sampling, which requires cold chain storage. The use of DBS has been shown to consistently result to lower EFV concentrations compared with plasma [15,21,22]. This was confirmed in our study in which DBS level was 33% lower than derived plasma level. The lower concentrations seen with DBS is mainly a result of the effect of hematocrit, which varies from person to person, and is generally lower in females than males. However, correcting for patient-specific hematocrit and protein binding of EFV with DBS levels has been shown to give similar results with concentrations in plasma [15]. Hence, we derived plasma concentrations from DBS by correcting for patient-specific hematocrit and protein binding of EFV, and performed subsequent analyses using the DBS-derived plasma concentrations.

Similar to previous reports [15], DBS concentrations of EFV correlated well with plasma concentrations in this study. Hair concentrations of EFV also showed strong correlations with plasma concentrations. This has implication in interpreting medication adherence. Strong correlation between hair and plasma concentration usually indicate consistency in patients’ adherence patterns. Some patients tend to increase compliance to medications on the days closer to their clinic visits. Such ‘white coat compliance’ will result in higher plasma concentration, but not hair concentrations, and thus poor correlation between drug concentrations in hair and plasma. Similar to the findings in this study, a study among South Africans showed a strong correlation between plasma and hair EFV concentrations [3]. In contrast, a study of Asians showed no significant correlation between plasma lopinavir concentrations and hair concentrations [23], suggesting white-coat compliance. Our results therefore suggested that white coat compliance was not a major problem in our setting.

In this study, we evaluated the influence of SNPs and other patient's demographics on hair and plasma concentrations of EFV, and explored the effects of EFV concentrations on neurocognitive performance among PWH in Nigeria. We found that only CYP2B6516 G>T and CYP2B6 983G>T significantly influenced concentrations of EFV in both plasma and hair. There have been inconsistent reports on the effects of demographics such as body weight, sex, race and age on plasma EFV concentrations in the literature. While some studies found associations with these covariates, others reported no association. Burger et al.[24] reported sex and race to be contributory factors to inter individual variability in plasma concentrations of EFV, but no association was found between weight and plasma concentrations in multivariate analysis. In contrast, another report revealed significant associations between weight and plasma EFV concentrations but found no significant relationship between sex and EFV concentrations [25]. Differences in methodology and the population studied may have contributed to the inconsistency in results from these studies, further confirming the influence of population diversity in drug response. In our study, no significant association was seen with sex, ethnicity, age or weight and EFV concentrations, although a trend was observed with weight in which lighter individuals tended to have higher EFV concentrations compared with heavier individuals. However, these results should be interpreted with caution considering the small sample size of our study.

In terms of genetic associations, composite CYP2B6 516 G>T and CYP2B6 983T>C accounted for about 35% of the observed variation in plasma EFV concentrations in the current study while weight accounted for only 3.2% of the variation. This finding is expected given reports from previous studies that certain SNPs in CYP2B6 display strong association with plasma EFV concentrations. Homozygosity for the rare allele of CYP2B6 516 G>T (CYP2B6 516TT) has consistently been associated with reduced EFV clearance compared with 516GT or 516GG [26–28]. Consistent with these reports, our study demonstrated approximately three-fold higher plasma concentrations within CYP2B6 516T homozygotes compared with G homozygotes. Similarly, about two-fold higher plasma concentrations were seen with heterozygosity for the CYP2B6 983T>C (983CT) compared with homozygosity in the common allele (983TT). Notably, the homozygous 983CC genotype was not found in the current study. A previous report revealed that individuals with 983CC genotype discontinued EFV-containing regimen early during treatment due to CNS side effects [29]. Another study in which participants were on EFV for a median duration of approximately 18 months also did not find the 983CC genotype in the population studied [30]. The participants in our study had been on EFV-containing ART for a median duration of 45 months. Thus, it is possible that individuals with the 983CC genotype were not represented in our study because they may have switched over to EFV-sparing regimen earlier; however, the small sample size of the study also likely contributed, considering the low frequency of the 983CC genotype reported in our population [31].

Measuring antiretroviral drug concentrations in hair has become a very useful tool for monitoring drug exposure over a relatively longer period. Drug levels in hair represents accumulated drug exposure over weeks to months. Hence, a hair drug level is not affected by day-to-day variation in plasma concentrations. In this study, about 1.5 cm of hair was measured and cut which represents about 6 weeks of drug accumulation since hair grows at an average of 1 cm/month [32].

Hair antiretroviral concentrations have been reported to predict treatment outcomes in multiple settings [33–35]. Many studies have shown the impact of some SNPs in CYP2B6 on hair concentrations of EFV [3,5]. These studies reported up to a three-fold increase in EFV hair concentrations with the homozygote rare allele of the CYP2B6 516G>T (516TT) compared with the G homozygote. Similar results were obtained in the current study in which individuals with CYP2B6516TT or CYP2B6983CT had approximately two-fold higher EFV hair concentrations compared with the CYP2B6516GG or CYP2B6983TT genotype, respectively. The effect of both SNPs (CYP2B6 516G>T and CYP2B6 983T>C) was further confirmed in linear regression in which CYP2B6 516G>T and CYP2B6 983T>C were independently associated with EFV hair concentrations with P less than 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively. These results further confirm the idea that pharmacogenetic testing of patients initiating EFV may be useful in identifying those predisposed to higher EFV levels and hence at increased possible risk of EFV-associated toxicities.

EFV has been associated with CNS toxicities, especially at higher concentrations [4,7,8]. In most persons, the CNS side effects resolve during treatment, but some patients experience persistent symptoms and therefore discontinue EFV. Contrary to previous reports, we found that total neuropsychological performance was significantly associated with plasma EFV concentrations but not hair concentrations. Higher EFV concentration even at supratherapeutic concentrations was associated with better neurocognitive performance. This may have been because the population studied were already tolerating EFV as our study evaluated the impact of EFV on patients who had been on the drug for a long time. Moreover, the majority of the patient population studied had viral loads less than 50 copies/ml within 6 months before hair and blood samples were collected. A previous report on the long-term impact (over 3 years) of EFV on neuropsychological performance revealed improvement in neuropsychological performance compared with baseline data [13]. In addition, some studies have reported association of antiretroviral drugs with improved cognitive performance whereby patients’ overall neurocognition improved as a result of ART [10,11,36]. Although the correlation between EFV concentrations and neurocognitive performance was statistically significant, its clinical significance is not certain. It is not clear why a stronger correlation with neurocognitive performance was observed for plasma concentration compared with hair concentrations in our study, but the fact that plasma concentration represents drug concentrations over a very short period while hair concentrations gives accumulation over a longer period may provide insight. The difference in the length of time of drug exposures for hair and plasma may have different mechanisms of association with neurocognitive performance. This may mean that the neurocognitive performance may depend more on the current concentration of EFV in the body as reflected by plasma concentrations. Given prior studies, we speculate that there is an underlying curve of EFV concentration in which neurotoxicity is approached at higher concentrations, but substantial neuro-efficacy is achieved as seen here in our findings.

The biggest limitation of our study is its cross-sectional nature. Furthermore, neurocognitive assessment was performed only once, although use of a comprehensive battery increased the robustness of our results. Further studies assessing short-term and long-term drug exposure over time and neurocognitive performance are needed. In addition, while this study has provided an insight to the relationship between EFV concentration and neurocognitive performance in this unique population, the small sample size in this study is a limitation. Finally, we were unable to assess the relationship between ethnicity differences EFV-related SNPs since the majority of our study population (86.8%) was of Yoruba ethnicity.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated an approximately three-fold increase in EFV exposure (assessed via both hair and plasma concentrations) within CYP2B6 516T homozygotes compared with G homozygotes and approximately two-fold increase within CYP 2B6 983CT compared with 983TT. This confirms the reports that CYP2B6 516G>T and CYP 2B6 983T>C are significant predictors of EFV plasma and hair concentrations and inter-individual variability in EFV pharmacokinetics even in our unique population. Higher EFV concentrations were associated with better neurocognitive performance in our study, requiring further study to elucidate the relationship between adherence, adverse effects and outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the staff of TPRC, University at Buffalo for their support and the BAF staff University of Liverpool, UK for technical support. We acknowledge the input of Dr Olayinka A. Kotila. We also acknowledge CDDDP, University of Ibadan for laboratory space.

Authors contributions: J.N.N. was involved in the conceptualization of the research, sample collection and analysis, data analysis and drafting of the article. M.G.; conceptualization of the research and drafting of the article, An.O.; sample analysis and revising, S.H.K.; sample analysis and data interpretation, B.T. was involved in the conceptualization of the research and drafting of the article, Ad. O., was involved in sample analysis, data analysis and revising of the article, B.B.; conceptualization of the research and revising of the article, H.O.; sample analysis and revising of the article, R.T. was involved in sample analysis and revising of the article, K.R. was involved in neurocognitive assessment and data analysis and C.P.B. was involved in the conceptualization of the research and drafting of the article.

Research training for this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number D43TW009608, PI – Professor Babafemi Taiwo. This work is partially supported by NIAID/NIH (2RO1AI098472 and R03 AI152773, PI Gandhi).The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. Update of recommendations on first- and second-line antiretroviral regimens. Geneva: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venter WDF, Moorhouse M, Sokhela S, Fairlie L, Mashabane N, Masenya M, et al. Dolutegravir plus two different prodrugs of tenofovir to treat HIV. N Engl J Med 2019; 381:803–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston J, Wiesner L, Smith P, Maartens G, Orrell C. Correlation of hair and plasma efavirenz concentrations in HIV-positive South Africans. South Afr J HIV Med 2019; 20:881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leger P, Chirwa S, Turner M, Richardson DM, Baker P, Leonard M, et al. Pharmacogenetics of efavirenz discontinuation for reported central nervous system symptoms appears to differ by race. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2016; 26:473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi M, Greenblatt RM, Bacchetti P, Jin C, Huang Y, Anastos K, et al. A single-nucleotide polymorphism in CYP2B6 leads to >3-fold increases in efavirenz concentrations in plasma and hair among HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1453–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desta Z, Gammal RS, Gong L, Whirl-Carrillo M, Gaur AH, Sukasem C, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2B6 and efavirenz-containing antiretroviral therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2019; 106:726–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukonzo JK, Okwera A, Nakasujja N, Luzze H, Sebuwufu D, Ogwal-Okeng J, et al. Influence of efavirenz pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics on neuropsychological disorders in Ugandan HIV-positive patients with or without tuberculosis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marzolini C, Telenti A, Decosterd LA, Greub G, Biollaz J, Buclin T. Efavirenz plasma levels can predict treatment failure and central nervous system side effects in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 2001; 15:71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummins NW, Neuhaus J, Chu H, Neaton J, Wyen C, Rockstroh JK, et al. Investigation of efavirenz discontinuation in multiethnic populations of HIV-positive individuals by genetic analysis. EBioMedicine 2015; 2:706–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson K, Jiang H, Kumwenda J, Supparatpinyo K, Evans S, Campbell TB, et al. Improved neuropsychological and neurological functioning across three antiretroviral regimens in diverse resource-limited settings: AIDS Clinical Trials Group study a5199, the International Neurological Study. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:868–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson KR, Robertson WT, Ford S, Watson D, Fiscus S, Harp AG, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy improves neurocognitive functioning. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004; 36:562–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma Q, Vaida F, Wong J, Sanders CA, Kao YT, Croteau D, et al. Long-term efavirenz use is associated with worse neurocognitive functioning in HIV-infected patients. J Neurovirol 2016; 22:170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clifford DB, Evans S, Yang Y, Acosta EP, Ribaudo H, Gulick RM. Long-term impact of efavirenz on neuropsychological performance and symptoms in HIV-infected individuals (ACTG 5097s). HIV Clin Trials 2009; 10:343–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amara AB, Else LJ, Tjia J, Olagunju A, Puls RL, Khoo S, et al. A validated method for quantification of efavirenz in dried blood spots using high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Ther Drug Monit 2015; 37:220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kromdijk W, Mulder JW, Rosing H, Smit PM, Beijnen JH, Huitema AD. Use of dried blood spots for the determination of plasma concentrations of nevirapine and efavirenz. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67:1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Y, Gandhi M, Greenblatt RM, Gee W, Lin ET, Messenkoff N. Sensitive analysis of anti-HIV drugs, efavirenz, lopinavir and ritonavir, in human hair by liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2008; 22:3401–3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Browne RW, Rosenkranz SL, Wang Y, Taylor CR, DiFrancesco R, Morse GD. Sources of variability and accuracy of performance assessment in the clinical pharmacology quality assurance proficiency testing program for antiretrovirals. Ther Drug Monit 2019; 41:452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson K, Jiang H, Evans SR, Marra CM, Berzins B, Hakim J, et al. International neurocognitive normative study: neurocognitive comparison data in diverse resource-limited settings: AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5271. J Neurovirol 2016; 22:472–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson K, Kumwenda J, Supparatpinyo K, Jiang JH, Evans S, Campbell TB, et al. A multinational study of neurological performance in antiretroviral therapy-naïve HIV-1-infected persons in diverse resource-constrained settings. J Neurovirol 2011; 17:438–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nwogu JN, Babalola CP, Ngene SO, Taiwo BO, Berzins B, Gandhi M. Willingness to donate hair samples for research among people living with HIV/AIDS attending a tertiary health facility in Ibadan, Nigeria. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2019; 35:642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amara AB, Else LJ, Carey D, Khoo S, Back DJ, Amin J, et al. Comparison of dried blood spots versus conventional plasma collection for the characterization of efavirenz pharmacokinetics in a large-scale global clinical trial – the ENCORE1 study. Ther Drug Monit 2017; 39:654–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Schooneveld T, Swindells S, Nelson SR, Robbins BL, Moore R, Fletcher CV. Clinical evaluation of a dried blood spot assay for atazanavir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54:4124–4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasitsuebsai W, Kerr SJ, Truong KH, Ananworanich J, Do VC, Nguyen LV, et al. Using lopinavir concentrations in hair samples to assess treatment outcomes on second-line regimens among Asian children. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015; 31:1009–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burger D, van der Heiden I, la Porte C, van der Ende M, Groeneveld P, Richter C, et al. Interpatient variability in the pharmacokinetics of the HIV nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor efavirenz: the effect of gender, race, and CYP2B6 polymorphism. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 61:148–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poeta J, Linden R, Antunes MV, Real L, Menezes AM, Ribeiro JP, et al. Plasma concentrations of efavirenz are associated with body weight in HIV-positive individuals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66:2601–2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swart M, Evans J, Skelton M, Castel S, Wiesner L, Smith PJ, et al. An expanded analysis of pharmacogenetics determinants of efavirenz response that includes 3′-UTR single nucleotide polymorphisms among Black South African HIV/AIDS patients. Front Genet 2015; 6:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viljoen M, Karlsson MO, Meyers TM, Gous H, Dandara C, Rheeders M. Influence of CYP2B6 516G>T polymorphism and interoccasion variability (IOV) on the population pharmacokinetics of efavirenz in HIV-infected South African children. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 68:339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas DW, Ribaudo HJ, Kim RB, Tierney C, Wilkinson GR, Gulick RM, et al. Pharmacogenetics of efavirenz and central nervous system side effects: an Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group study. AIDS 2004; 18:2391–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyen C, Hendra H, Vogel M, Hoffmann C, Knechten H, Brockmeyer NH, et al. Impact of CYP2B6 983T>C polymorphism on nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 61:914–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olagunju A, Bolaji O, Amara A, Waitt C, Else L, Adejuyigbe E, et al. Breast milk pharmacokinetics of efavirenz and breastfed infants’ exposure in genetically defined subgroups of mother–infant pairs: an observational study. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:453–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 2010; 467:1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeBeau MA, Montgomery MA, Brewer JD. The role of variations in growth rate and sample collection on interpreting results of segmental analyses of hair. Forensic Sci Int 2011; 210:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gandhi M, Ameli N, Bacchetti P, Anastos K, Gange SJ, Minkoff H, et al. Atazanavir concentration in hair is the strongest predictor of outcomes on antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:1267–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koss CA, Natureeba P, Mwesigwa J, Cohan D, Nzarubara B, Bacchetti P, et al. Hair concentrations of antiretrovirals predict viral suppression in HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding Ugandan women. AIDS 2015; 29:825–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baxi SM, Greenblatt RM, Bacchetti P, Jin C, French AL, Keller MJ, et al. Nevirapine concentration in hair samples is a strong predictor of virologic suppression in a prospective cohort of HIV-infected patients. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0129100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson KR, Jiang H, Kumwenda J, Supparatpinyo K, Marra CM, Berzins B, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive impairment in diverse resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:1733–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]