Abstract

PURPOSE:

Responses to the opioid epidemic in the United States, including efforts to monitor and limit prescriptions for noncancer pain, may be affecting patients with cancer. Oncologists' views on how the opioid epidemic may be influencing treatment of cancer-related pain are not well understood.

METHODS:

We conducted a multisite qualitative interview study with 26 oncologists from a mix of urban and rural practices in Western Pennsylvania. The interview guide asked about oncologists' views of and experiences in treating cancer-related pain in the context of the opioid epidemic. A multidisciplinary team conducted thematic analysis of interview transcripts to identify and refine themes related to challenges to safe and effective opioid prescribing for cancer-related pain and recommendations for improvement.

RESULTS:

Oncologists described three main challenges: (1) patients who receive opioids for cancer-related pain feel stigmatized by clinicians, pharmacists, and society; (2) patients with cancer-related pain fear becoming addicted, which affects their willingness to accept prescription opioids; and (3) guidelines for safe and effective opioid prescribing are often misinterpreted, leading to access issues. Suggested improvements included educational materials for patients and families, efforts to better inform prescribers and the public about safe and appropriate uses of opioids for cancer-related pain, and additional support from pain and/or palliative care specialists.

CONCLUSION:

Challenges to safe and effective opioid prescribing for cancer-related pain include opioid stigma and access barriers. Interventions that address opioid stigma and provide additional resources for clinicians navigating complex opioid prescribing guidelines may help to optimize cancer pain treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer-related pain is a significant public health issue1 for which opioids remain a mainstay of treatment.2 The current epidemic of opioid misuse and addiction has led to changing attitudes regarding opioid treatment and new guidelines and state laws designed to limit unnecessary opioid prescriptions. Although these initiatives typically exclude patients with cancer-related pain, multiple recent analyses find declines in opioid prescribing among oncologists,3-5 raising concerns that initiatives intended to exclude patients with cancer-related pain may be inadvertently affecting them.

To date, there has been little exploration of oncologists' views on how the opioid epidemic may be influencing management of cancer-related pain. The perspectives of oncologists, who are at the forefront of treating patients with cancer-related pain, can help to contextualize recent trends, highlight barriers to safe and effective opioid prescribing, and identify opportunities to improve patient experiences and outcomes. Therefore, we designed an in-depth interview study with oncologists from Western Pennsylvania, an epicenter of the opioid epidemic, to understand how this crisis has affected treatment of cancer-related pain.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

We included medical oncologists with active outpatient practices at one of > 45 UPMC Hillman Cancer Center medical oncology clinics in Western Pennsylvania. Oncologists were classified as rural or urban based on the location of their clinical practice, using the Center for Rural Pennsylvania definition of rural.6 Within these strata, we selected oncologists to approach using a random number generator. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

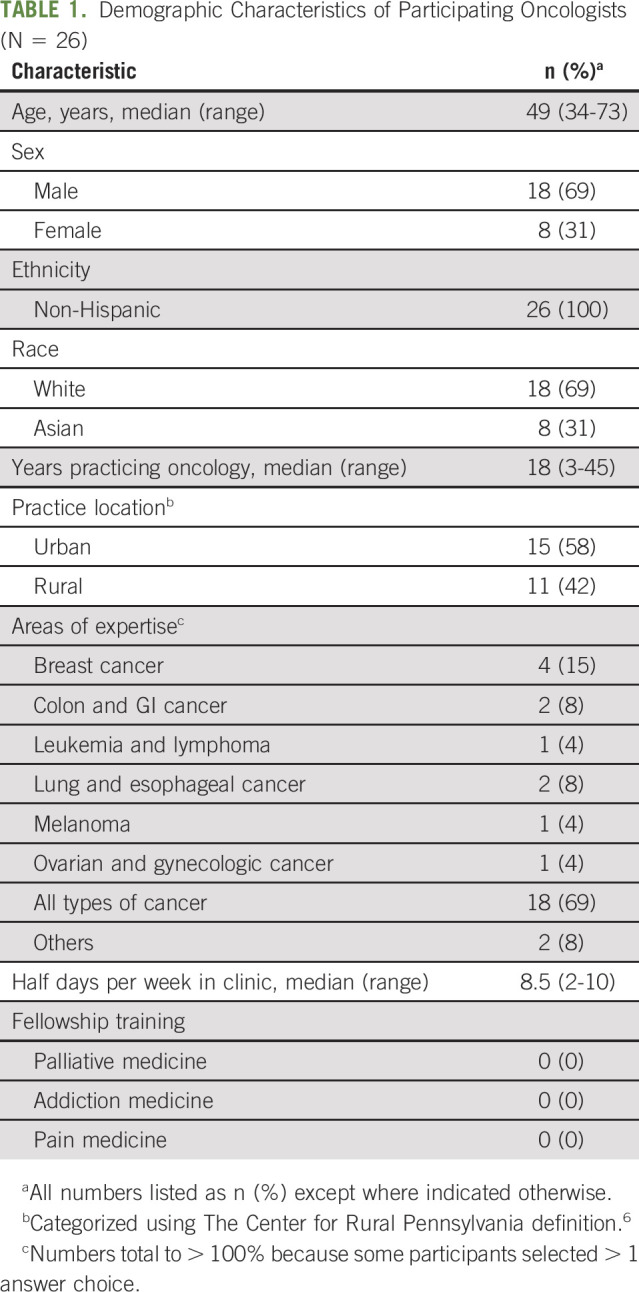

Oncologists were approached for interviews via e-mail and provided verbal consent before participation. Participating oncologists (N = 26) worked at 18 different medical oncology practices, with a roughly equal distribution between rural and urban locations. Nine additional oncologists were approached but declined participation. Participants were experienced physicians (median, 18; range, 3-45 years practicing oncology); none had completed additional fellowship training in palliative care, addiction, or pain medicine. Additional demographics are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participating Oncologists (N = 26)

Data Collection

Content and qualitative methodology experts on the study team drafted an interview guide with questions related to oncologists' views of and experiences in treating cancer-related pain in the context of the opioid epidemic. Nonleading questions asked participants to reflect on their own patients and discuss a hypothetical patient presented in a brief vignette. The team made minor modifications to the interview script after piloting with two oncologists (see the Data Supplement [online only] for the full interview guide).

A trained interviewer with 2 years of previous interviewing experience (A.D.) conducted all interviews by telephone from a private office between August 2019 and July 2020. Interviews averaged 36 ± 8 minutes (range, 25-55 minutes). Interviews continued until the interviewer determined, through review of her interview notes, that thematic saturation had been achieved (ie, the point at which no new themes or information were arising in additional interviews). The study team (S.B. and assistant) transcribed the audio files verbatim, with identifying details redacted.

Qualitative Analysis

We used a qualitative description approach, seeking to describe oncologists' views of and experiences in treating cancer-related pain in the context of the opioid epidemic.7 We conducted a thematic analysis to do so.8-10 Although our study goals were broader, the analysis presented here focused on challenges to safe and effective opioid prescribing. A member of the study team (R.W.) reviewed all transcripts to inductively create a draft codebook reflecting the contents of the qualitative data. The multidisciplinary study team reviewed the draft codebook to ensure that constructs of interest were included. We completed coding with the assistance of Atlas.ti. Two trained, experienced qualitative coders with backgrounds in Psychology and Sociology (A.D.) and Anthropology (R.W.) independently applied the codebook to five of the transcripts and met to discuss coding discrepancies, modifying code definitions as necessary to clarify when codes should be applied. The two coders then independently applied the codebook to 10 transcripts, and the primary coder (R.W.) calculated kappa scores to measure intercoder reliability. The average kappa score was 0.64, interpreted as moderate agreement.11 Coders fully resolved all coding discrepancies through discussion. No discrepancies required the intervention of a third party to resolve. The primary coder then coded the remaining transcripts and produced a thematic analysis of the interviews using the finalized codebook. Themes were confirmed by the secondary coder and discussed with the larger study team to determine how themes found in the present study might confirm, refute, or further contribute to existing knowledge in this area, as a form of investigator triangulation. We conducted member checking to enhance the validity of our findings.

RESULTS

Oncologists described three major challenges to safe and effective opioid prescribing and offered several suggestions for improvement. The following themes were common across rural and urban providers.

Patients Who Receive Opioids for Cancer-Related Pain Feel Stigmatized by Clinicians, Pharmacists, and Society

Oncologists observed that patients taking opioids for cancer-related pain sometimes felt treated like drug addicts or junkies in encounters with other clinicians, pharmacists, or the health system (Table 2). One participant described a situation when she was out of town and her partners were asked to sign an opioid prescription:

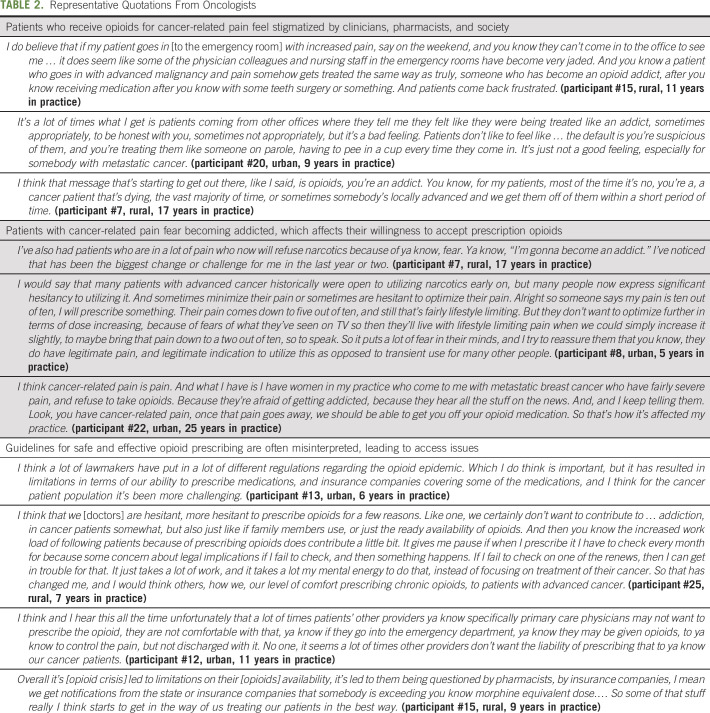

TABLE 2.

Representative Quotations From Oncologists

there's just this hesitation that prescribing the medication when ya know they obviously, there's a legitimate reason for them to have the, ya know the pain. And sometimes … they [patients] feel that they're being perceived as ya know “a junkie.” Ya know which is really unfortunate. (participant #12, urban, 11 years in practice)

Oncologists described these encounters as demoralizing to patients, leading to additional challenges in treating cancer-related pain. One participant described a stigmatizing encounter that a patient experienced when picking up her opioid prescription:

And, I think there's been, which is very unfortunate, a change in the attitude of the pharmacists. I actually had one patient one day who said that I refuse to take … to pick up my prescription because the way the pharmacist looks at me, he talks to me, and makes me think like I'm a drug addict. And I actually had to convince that person to take the pain medication for her, and explained that unfortunately the population that pharmacist sees might be a different population and they might just be generalizing. And I think it's a little bit unfair to cancer patients, getting impacted by this in a negative way. (participant #19, urban, 20 years in practice)

Participants described public health campaigns related to the opioid epidemic leaving the public uncertain about when opioids are appropriately prescribed and for whom they may be appropriate. As one oncologist noted, “it's permeating on TV. I mean there's commercials all the time that are bringing it [opioid addiction] up again and again. That there's been kind of re-looking at how our narcotics are given in general.” (participant #24, rural, 28 years in practice) Oncologists recognized that this confusion may lead to stigmatizing beliefs about patients who receive prescription opioids for cancer-related pain. Another participant noted, “you know that person who has long term pain medication use after a knee surgery is not the same as somebody who is dying from pancreas cancer. And … we shouldn't treat them the same way.” (participant #15, rural, 9 years in practice)

Patients With Cancer-Related Pain Fear Becoming Addicted, Which Affects Their Willingness to Accept Prescription Opioids

Oncologists described recent challenges with patients who were afraid to take opioids because of fears of becoming addicted (Table 2). As one oncologist said, “I've had patients that clearly have cancer related pain, advanced cancers, who won't treat their pain because of fear of addiction because they're told opioids equal addiction. Ya know, that's really the public perception now.” (participant #7, rural, 17 years in practice)

Participants noted that even when family members were supportive, patients may be reluctant to take opioids. As one oncologist described:

I have people who come in who have heard about this, and say listen, I just don't want to get addicted to the pain medicine. So they refuse to take [opioids], and you've got the family members there, saying please take it, you need it. You know, it's just I don't want to get addicted. I mean I've had that happen a number of times. And these [are] people who are suffering. (participant #22, urban, 25 years in practice)

Oncologists often did not share patients' concerns about addiction and reported that they did not often see addiction in their patients. However, they described difficulty in effectively treating cancer-related pain given these fears. As another oncologist noted:

I haven't really had too many experiences with patients actually becoming addicted. In fact, I've actually had the opposite, where it's very difficult sometimes to get patients to even go on pain medicines when they clearly need them. Even when they [are] … riddled with bone lesions and clearly are in pain, there is a fear among most cancer patients that they're going to become addicted to this. (participant #3, urban, 11 years in practice)

Guidelines for Safe and Effective Opioid Prescribing Are Often Misinterpreted, Leading to Access Issues

Oncologists gave multiple examples of prescribing regulations and restrictions that were not designed for cancer-related pain “bleeding over into the oncology world” (participant #7, rural, 17 years in practice) (Table 2). Examples included insurance regulations that were limiting patients to shorter courses of opioids, limited insurance coverage for certain opioid medications, and preauthorization requirements for certain opioid medications. One oncologist described these burdens for a patient as follows:

He had terminal stage four renal cell and brain mets. And for some reason, the insurance that he had, and his pharmacy would only let him have seven days. Well he also didn't have any transportation. So he had to rely on people for transportation. And no matter what we did, we could never get the pharmacy to understand through its head that he was dying from cancer, and that he didn't have transportation and that he really just needed to have his thirty-day prescription of narcotics filled. (participant #7, rural, 17 years in practice)

Oncologists not only recognized some of these regulations as necessary to decrease the overall supply of opioids and minimize opioid misuse risks but also described worries that their patients were suffering as a result.

I think that unfortunately because of the opioid epidemic all patients on opioids are put in one category as an opioid user, regardless of whether or not they have advanced pancreatic cancer versus having a recent bunionectomy that might require five pills of a low dose narcotic. I think that it has become profoundly cumbersome for our cancer patients for the different hoops for them to … jump through in order to procure their narcotics. That being said, I think it's a necessary evil in order to decrease the overall supply of available medication in the general population. (participant #8, urban, 5 years in practice)

Oncologists described a variety of issues with prescribing opioids, including increased oversight and workload. As this participant said,

the opioid rules or prescribing rules are supposed to be for non-cancer related pain. And somehow, medical oncologists and their patients are getting lumped into that. And, I've seen where it impacts sometimes my comfort level with prescribing because it's like you know somebody's monitoring something they really shouldn't be because I'm writing [opioids] for cancer-related pain. (participant #7, rural, 17 years in practice)

Several participants noted that other physicians (especially primary care doctors and emergency room physicians) were no longer willing to prescribe opioids for their patients, further contributing to oncologists' workload and creating access barriers for their patients. As this oncologist said, “It [the opioid epidemic] has made family doctors very hesitant to you know start or manage any pain medication for patients with advanced cancer.… So a lot more of it falls to us.” (participant #15, rural, 9 years in practice)

Oncologists practicing with collocated specialty palliative care services appreciated having the opportunity to refer their patients for pain management. However, oncologists practicing in settings without access to specialty palliative care noted that the absence of these services created additional burdens for oncologists and may lead to some patients not getting their pain managed at all:

I know there's a fair number of primary care doctors that just won't prescribe controlled substances period anymore. … it wouldn't shock me that … at academic centers, where these type of palliative care or pain management resources are more readily accessible, that they're just referring people to palliative care for pain management.… I don't really have the option of doing that here. I don't have someone locally that I can refer to who's going to prescribe narcotics. It's they get it from me or they don't get it, essentially. (participant #20, urban, 12 years in practice)

Recommendations to Improve Safe and Effective Opioid Prescribing for Patients With Cancer-Related Pain

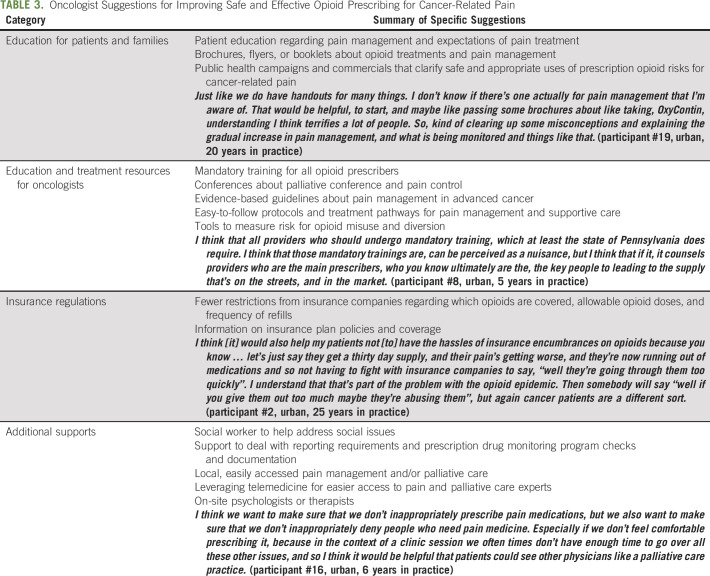

Oncologist recommendations for improving safe and effective opioid prescribing in cancer are summarized in Table 3. Participants recommended educational materials for patients and families about the appropriate role for opioids in cancer-related pain, suggesting that this education occur both within oncology practices and through public health campaigns. Additional recommendations included more education and guidelines for oncologists about the risks and benefits of opioid use, fewer insurance restrictions on prescribing opioids for cancer-related pain, and additional clinical supports.

TABLE 3.

Oncologist Suggestions for Improving Safe and Effective Opioid Prescribing for Cancer-Related Pain

DISCUSSION

In this in-depth interview study with oncologists from a mix of rural and urban practices in Western Pennsylvania, we found multiple ways in which the opioid epidemic may be affecting treatment of cancer-related pain. Oncologists expressed concerns that their patients experience opioid-related stigma, with the potential to undermine safe and effective pain management. In addition, structural issues (eg, misapplied insurance regulations) create barriers for patients who are willing to accept opioid medications. Suggestions to improve safe and effective opioid prescribing for cancer-related pain centered on educational needs, regulatory issues, and additional resources needed to support the challenges of treating cancer-related pain amid an opioid epidemic.

Our findings build on previous qualitative and quantitative work characterizing opioid stigma among patients with cancer.12,13 Cancer pain is broadly recognized as a complex, dynamic challenge throughout treatment, and opioids are recommended for the management of moderate-to-severe cancer pain.14 However, as the opioid epidemic grows, prescription opioid use is viewed with increasing fear and suspicion, resulting in negative stereotypes, judgment, and discrimination. Oncologists described patients with advanced cancer experiencing fear of addiction, labeling drug addicts, and negative interactions with clinicians and pharmacists that could lead them to limit or withdraw entirely from opioid pain management (eg, refuse to pick up their prescription after a stigmatizing encounter).

Opioid prescribing for patients with cancer is made more complex by the reality that some patients are at risk for opioid misuse.15,16 Oncologists in our study emphasized that patients with cancer are a different population from patients receiving opioids for noncancer pain and, despite being located in an opioid crisis epicenter, described few personal patient experiences with addiction. However, safe and effective pain management for patients with cancer requires recognizing patient fears of addiction and carefully assessing risk for opioid misuse, to ensure a successful balance between opioid efficacy and safety.17

Our findings also illustrate that structural barriers designed to decrease inappropriate opioid use may have unintended consequences on oncologists' ability to prescribe opioids for cancer-related pain. A recent consensus panel highlighted the potential for inflexible and inappropriate application of opioid prescribing recommendations to harm patients with cancer.18,19 A 2019 report issued by the US Department of Health and Human Services also discussed the risks of misapplying the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain to patients who are in active cancer treatment.20 Our data suggest that restrictions on opioid prescribing, coupled with the reluctance of many physicians to prescribe opioids at all, have added to oncologists' workloads. Safe and effective opioid prescribing for cancer requires continually re-evaluating opioid risks and benefits, addressing opioid stigma, navigating insurance regulations, and assuming responsibility for prescriptions that might previously have been handled by other clinicians (eg, emergency room or primary care physicians). Particularly in rural communities, participants noted that they did not have access to pain and palliative care specialists,21 who are helpful to their colleagues in more urban and academic settings. The critical importance of adequately treating cancer-related pain as a component of high-quality cancer care may require additional resources for community oncology practices.

Our study has limitations. We interviewed oncologists from 18 different oncology practices within a single cancer center network in Western Pennsylvania. We chose these settings to represent a range of rural and urban practices within a region of the country with high rates of opioid misuse. Findings may not generalize to clinicians in other health systems or other parts of the country with lower rates of opioid misuse. We did not include advance practice providers who also prescribe opioids. Data represent oncologist views and may not reflect actual prescribing practices. Data also do not include the views of patients with cancer or their family members. We plan to include these important perspectives in future work.

In conclusion, oncologists describe challenges to safe and effective opioid prescribing related to opioid stigma and structural barriers. Educational materials, public health campaigns, and additional support from pain and/or palliative care specialists may provide additional resources for oncologists navigating complex opioid prescribing guidelines and help to optimize cancer pain treatment.

Megan Hamm

Employment: Arcadia Health Solutions

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by a grant from the Hillman Development Fund and the Palliative Research Center (PaRC) at the University of Pittsburgh. This project used resources provided through the Clinical Protocol and Data Management and Protocol Review and Monitoring System, which are supported in part by award P30CA047904.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Yael Schenker, Hailey W. Bulls, Jessica S. Merlin, Alicia Dawdani, Lindsay M. Sabik

Financial support: Yael Schenker, Lindsay M. Sabik

Administrative support: Yael Schenker

Provision of study materials or patients: Yael Schenker

Collection and assembly of data: Yael Schenker, Megan Hamm, Jessica S. Merlin, Alicia Dawdani, Shane Belin

Data analysis and interpretation: Yael Schenker, Megan Hamm, Hailey W. Bulls, Jessica S. Merlin, Rachel Wasilko, Alicia Dawdani, Balchandre Kenkre, Lindsay M. Sabik

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This Is a Different Patient Population: Opioid Prescribing Challenges for Patients With Cancer-Related Pain

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Megan Hamm

Employment: Arcadia Health Solutions

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, et al. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis J Pain Symptom Manage 511070–1090.e92016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swarm RA, Paice JA, Anghelescu DL, et al. Adult cancer pain, version 3.2019 J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 17977–10072019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal A, Roberts A, Dusetzina SB, et al. Changes in opioid prescribing patterns among generalists and oncologists for Medicare part D beneficiaries from 2013 to 2017 JAMA Oncol 61271–12742020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graetz I, Yarbrough CR, Hu X, et al. Association of mandatory-access prescription drug monitoring programs with opioid prescriptions among Medicare patients treated by a medical or hematologic oncologist JAMA Oncol 61102–11032020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haider A, Zhukovsky DS, Meng YC, et al. Opioid prescription trends among patients with cancer referred to outpatient palliative care over a 6-year period J Oncol Pract 13e972–e9812017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Center for Rural Pennsylvania . Rural Urban Definitions. 2014. https://www.rural.palegislature.us/demographics_rural_urban.html [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandelowski M.Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Heal 23334–3402000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun V, Clarke V.Using thematic analysis in psychology Qual Res Psychol 377–1012006 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T.Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study Nurs Heal Sci 15398–4052013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHugh ML.Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic Biochem Med 22276–2822012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulls HW, Hoogland AI, Craig D, et al. Cancer and Opioids: Patient Experiences With Stigma (COPES)—A pilot study J Pain Symptom Manage 57816–8192019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meghani SH, Wool J, Davis J, et al. When patients take charge of opioids: Self-management concerns and practices among cancer outpatients in the context of opioid crisis J Pain Symptom Manage 59618–6252020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Adult Cancer Pain. 2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paice JA.Navigating cancer pain management in the midst of the opioid epidemic Oncology (Williston Park) 32386–390, 4032018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carmichael A-N, Morgan L, Del Fabbro E. Identifying and assessing the risk of opioid abuse in patients with cancer: An integrative review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:71. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S85409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paice JA.Cancer pain management and the opioid crisis in America: How to preserve hard-earned gains in improving the quality of cancer pain management Cancer 1242491–24972018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Alford DP, Argoff C, et al. Challenges with implementing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention opioid guideline: A consensus panel report Pain Med 20724–7352019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R.No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing N Engl J Med 3802285–22872019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services . Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu JA, Ray KN, Park SY, et al. System-level factors associated with use of outpatient specialty palliative care among patients with advanced cancer J Oncol Pract 15e10–e192019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]