Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has serious social, economic and health consequences. Particularly in these times, it is important to maintain individual health. Therefore, it is important to take part in routine health checkups. Consequently, our objective was to describe the frequency and to identify the determinants of postponed routine health checkups.

Study design

Cross-sectional data from the nationally representative online-survey “COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring in Germany (COSMO)” was used (wave 17; July 2020).

Methods

In sum, 974 individuals were included in our analytical sample (average age was 45.9 years, SD: 16.5, 18–74 years). Postponed routine health checkups (yes or no) since March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic were assessed.

Results

More than 16% of the individuals reported postponed routine health checkups in the past few months due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Particularly, individuals aged 30–49 years had postponed health checkups (21%). The probability of postponed health checkups was positively associated with the presence of chronic diseases (odds ratio [OR]: 1.68, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.15–2.47), higher affect regarding COVID-19 (OR: 1.44, 95%-CI: 1.16–1.78), and higher presumed severity of COVID-19 (OR: 1.17, 95%-CI: 1.01–1.35), whereas the outcome measure was not associated with socioeconomic factors. Data showed that a sizeable part (about one of six individuals) of the population reported postponed routine health checkups due to the COVID-19 pandemic between March and July 2020.

Conclusions

Postponed checkups should not be neglected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals at risk for postponed health checkups should be appropriately addressed.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, General medical examination, Preventive health examination, Routine health checkups, Screening

Introduction

Routine health checkups are offered in various countries. Such routine health checkups are also known as general health checks, periodic health evaluations, preventive health examinations or general medical examinations. For instance, since the late 80s, a triannual routine health checkup can be used free of charge by members of statutory health insurance aged 35 years and over in Germany. This checkup starts with taking the medical history (e.g. pre-existing illnesses, illnesses of family members) followed by a whole-body examination and laboratory tests including the investigation of blood cholesterol levels or examination of the urine. Finally, the doctor will inform the patient about the results of this checkup and will develop an individual risk profile for the patient. Moreover, recommendations regarding a healthy lifestyle will be provided. Further checkups or a treatment follow when an illness is suspected or in case of diagnosis.

By contrast, these examinations do not cover vaccination or cancer screenings. Several parts of these checkups have been shown to be effective.1 , 2 Moreover, in Germany, adults between 18 and 34 years of age can have a onetime health check by their family doctor (also free of charge). However, it should be noted that blood tests are only carried out for those younger adults (18–34 years) with a corresponding risk profile (e.g. hypertension, obesity, or pre-existing illnesses in the family). In Germany, the patient can simply arrange an appointment with the family doctor for this routine health checkup. Although governments in several countries promote and recommend routine health checkups, voluntary health checkups are used infrequently (e.g. in Germany3). Several studies have examined the factors associated with the use of routine health checkups in Germany4, 5, 6 in the past years. Studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic have revealed that an increased likelihood of routine health checkups is associated with higher income, higher educational levels, and being female.5 , 6 However, the previous studies focused on actual (non)-attendance rather than postponed health checkups. More precisely, to date, nationally representative studies are lacking investigating the factors associated with postponed routine health checks generally and particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. It should be noted that it is difficult to compare these studies conducted before the pandemic with our present study taking place during the pandemic. Particularly, it appears to be plausible that determinants related to the fear of being infected with COVID-19 may be a main driver of postponing routine health checks during the pandemic.

Serious challenges for health and the healthcare system are linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is particularly important to avoid postponing routine health checkups in these times (when individual risks of getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 and having a severe course of COVID-19 are low) because it has been reported that postponed routine health checkups can have important long-term health consequences.2 Moreover, it has been suggested that routine health checkups can improve the doctor–patient relationship.7 This relationship can have a clear impact on satisfaction8 and health9 of patients as well as general healthcare costs.9

Hence, the goal of this study is to describe the proportion of postponed routine health checkups due to the COVID-19 pandemic and to identify the determinants based on nationally representative data. Knowledge about the factors associated with this may help characterizing individuals at risk for these postponed checkups during this pandemic.

In the case of Germany, corona measures were implemented in Mid-March 2020 (16th March). For example, schools were closed. Efforts were intensified in the following week (22nd March) by imposing travel bans or public contact restrictions. These actions were prolonged in the following weeks. However, in mid-April (20th April), some measures were loosened such as reopening shops falling below a certain size. Schools gradually opened in early May (4th May). Moreover, other restrictions such as contact bans were also loosened in May. In addition, further restrictions were loosened in June (with the possibility to tighten the restrictions if the infection rate increases). With regard to the healthcare sector, it should be noted that in hospitals elective surgery (e.g. knee replacement) was postponed since mid-March 2020 in Germany.10 Moreover, a recent scoping review11 identified a lack of (qualitative and quantitative) studies determining whether and why outpatient appointments did not take place (e.g. due to capacity restrictions, or because patients canceled appointments) during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. However, a recent nationally representative study showed that perceived past and future access to healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany is reasonably good.12 Furthermore, international studies showed that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection is a main reason for avoidance behavior (e.g. delayed access to hospital care13 , 14). Thus, we assume that particularly patients canceled appointments.

Methods

Sample

For this present study, we used data from the COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO)15 starting in early March (wave 1, 3rd to 4th March). More precisely, in our study, cross-sectional data from wave 17 were used which included 1001 individuals (ranging from 18 to 74 years) for reasons of data availability. Wave 17 took place from 21st to 22nd July. Individuals were recruited online via the market research company Respondi using a procedure enabling that the distribution in the sample matches the distribution of age as well as gender and federal state in the adult population in Germany.16

The COSMO study is a joint project of the University of Erfurt, the Robert Koch Institute, the Leibniz Centre for Psychological Information and Documentation, the Science Media Center, the Bernhard-Nocht-Institute for Tropical Medicine and the Yale Institute for Global Health. It includes topics such as demographics, knowledge, protective behaviors, perceptions, and trust.15 Factors such as changes in knowledge or risk perceptions can be investigated over time. Moreover, misinformation or potential stigma can be determined.15

Dependent variable

Comparable with the question used in the German Ageing Survey (quantifying the utilization of routine health checkups), individuals responded to the question whether they postponed a routine health checkup since March 2020 for reasons of the COVID-19 pandemic. Answer options were as follows: 1 = “Yes”, 2 = “No, attended as planned”, 3 = “No examination pending”, and 4 = “No, other reasons”. Subsequently, the dependent variables was dichotomized (no, not postponed = 0; yes, postponed = 1). It is worth noting that we performed a pretest with 14 individuals. They supported the high face validity of the survey instrument.

Independent variables

Various sociodemographic variables were used in our study, namely age group (four groups: 18–29 years; 30–49 years; 50–64 years; ≥ 65 years), sex (women; men), having children < 18 years (no; yes), married/in a relationship (no; yes), housing situation (living alone; ≥ 2 individuals in household), size of the town (four categories: municipality/small town [1–20,000 individuals]; medium-sized town [20,001–100,000 individuals]; small city [100,001–500,000 individuals]; big city [>500,000 individuals]), COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population (below median; above median), level of education (≤9 years; ≥ 10 years (without general qualification for university entrance); ≥10 years (with general qualification for university entrance)), self-employment (no; yes), background of migration (no; yes), and presence of chronic diseases (no; yes).

In addition, affect with regard to a COVID-19 infection was included in the regression model. The instrument consists of seven items (in each case: ranging from 1 to 7). For instance, items are (after the introductory sentence “For me, the new type of corona virus is …”): “spreading slowly” (1) to “spreading quickly” (7) or “concerning” (1) to “not concerning” (7). The final scale was built by averaging the items. In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.78. Moreover, the presumed severity regarding a COVID-19 infection was quantified (exact wording was “How do you assess an infection with the novel corona virus for yourself?”, ranging from 1 (completely harmless) to 7 (extremely dangerous)). An overview about the questions used in the present study is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

First, we report sample characteristics for the analytical sample stratified by our dependent variable (i.e. whether or not individuals postponed routine health checkups since March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic). Afterward, we conducted multiple logistic regressions to identify the determinants of postponed routine health checkups due to the pandemic. The statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Stata 16.0 was used to perform statistical analyses (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Sample characteristics

Characteristics of our analytical sample in wave 17 are depicted in Table 1 . The mean age was 45.9 years (SD: 16.5 years) and 48.9% of the individuals were male. Bivariately, the outcome measure (postponed routine health checkups) was associated with higher age, presence of children under 18 years, the presence of chronic diseases as well as affect regarding COVID-19 and presumed severity of COVID-19. Additional details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (analytical sample with n = 974 individuals) at wave 17.

| Variables | Postponed routine health checkups |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, postponed routine health checkups |

No, attended as planned |

No examining pending |

No, other reasons |

P-value | |

| Mean (SD)/n (%) | Mean (SD)/n (%) | Mean (SD)/n (%) | Mean (SD)/n (%) | ||

| Sex | 0.12 | ||||

| Men | 65 (13.7%) | 121 (25.4%) | 279 (58.6%) | 11 (2.3%) | |

| Women | 93 (18.7%) | 105 (21.1%) | 287 (57.6%) | 13 (2.6%) | |

| Age category | <0.001 | ||||

| 18–29 years | 23 (12.2%) | 29 (15.3%) | 134 (70.9%) | 3 (1.6%) | |

| 30–49 years | 75 (21.4%) | 59 (16.9%) | 204 (58.3%) | 12 (3.4%) | |

| 50–64 years | 41 (15.2%) | 61 (22.6%) | 161 (59.6%) | 7 (2.6%) | |

| 65 years and over | 19 (11.5%) | 77 (46.7%) | 67 (40.6%) | 2 (1.2%) | |

| Children under 18 years: | <0.05 | ||||

| No | 109 (15.1%) | 181 (25.1%) | 417 (57.7%) | 15 (2.1%) | |

| Yes | 49 (19.4%) | 45 (17.9%) | 149 (59.1%) | 9 (3.6%) | |

| Education | 0.68 | ||||

| Up to 9 years/10 years and more (without general qualification for university entrance) | 67 (15.1%) | 106 (24.0%) | 257 (58.0%) | 13 (2.9%) | |

| 10 years and more (with general qualification for university entrance) | 91 (17.1%) | 120 (22.6%) | 309 (58.2%) | 11 (2.1%) | |

| Town size | 0.60 | ||||

| Municipality/small town (1–20,000) | 58 (14.5%) | 101 (25.1%) | 230 (57.2%) | 13 (3.2%) | |

| Medium sized town (20,001–100,000) | 42 (17.5%) | 54 (22.5%) | 138 (57.5%) | 6 (2.5%) | |

| Small city (100,001–500,000) | 26 (18.3%) | 27 (19.0%) | 85 (59.9%) | 4 (2.8%) | |

| Big city (>500,000) | 32 (16.8%) | 44 (23.2%) | 113 (59.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Region | 0.95 | ||||

| West Germany | 135 (16.5%) | 188 (23.0%) | 474 (58.0%) | 20 (2.5%) | |

| East Germany | 23 (14.7%) | 38 (24.2%) | 92 (58.6%) | 4 (2.5%) | |

| Cases/100,000 population | 0.34 | ||||

| Below median | 70 (15.0%) | 102 (21.8%) | 282 (60.2%) | 14 (3.0%) | |

| Above median | 88 (17.4%) | 124 (24.5%) | 284 (56.1%) | 10 (2.0%) | |

| Relationship/marriage | 0.41 | ||||

| No | 48 (14.2%) | 78 (23.2%) | 205 (60.8%) | 6 (1.8%) | |

| Yes | 110 (17.3%) | 148 (23.2%) | 361 (56.7%) | 18 (2.8%) | |

| Living situation | 0.71 | ||||

| Living alone | 40 (15.8%) | 62 (24.5%) | 147 (58.1%) | 4 (1.6%) | |

| At least 2 individuals in the same household | 118 (16.4%) | 164 (22.7%) | 419 (58.1%) | 20 (2.8%) | |

| Migration background: | 0.99 | ||||

| No | 134 (16.3%) | 191 (23.2%) | 478 (58.1%) | 20 (2.4%) | |

| Yes | 24 (15.9%) | 35 (23.2%) | 88 (58.3%) | 4 (2.6%) | |

| Self-employment | 0.62 | ||||

| No | 142 (16.1%) | 206 (23.3%) | 515 (58.3%) | 20 (2.3%) | |

| Yes | 16 (17.6%) | 20 (22.0%) | 51 (56.0%) | 4 (4.4%) | |

| Chronic disease | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 79 (13.0%) | 108 (17.7%) | 409 (67.2%) | 13 (2.1%) | |

| Yes | 79 (21.6%) | 118 (32.3%) | 157 (43.0%) | 11 (3.0%) | |

| Affect regarding COVID-19: COVID-19 infection (from 1 to 7; higher values correspond to higher affect regarding COVID-19) | 4.6 (1.0) | 4.1 (1.0) | 4.1 (1.0) | 4.0 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Presumed severity of COVID-19 infection (from 1 to 7; higher values correspond to higher severity) | 4.7 (1.6) | 4.5 (1.6) | 4.0 (1.5) | 4.2 (1.7) | <0.001 |

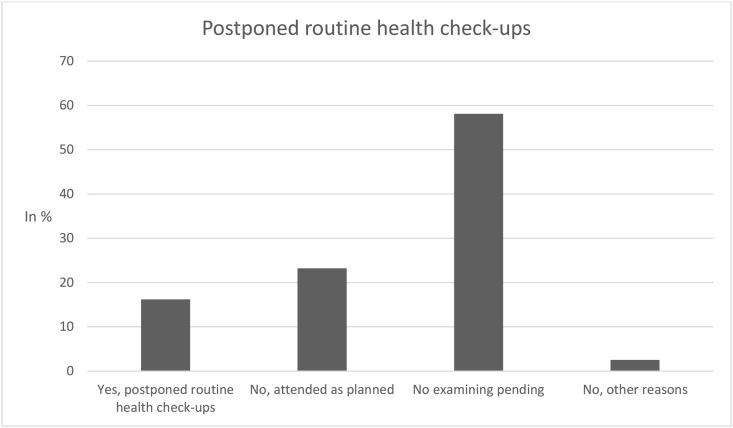

In total (see Fig. 1 ), 16.2% of the individuals had postponed routine health checkups in the past months for reasons of the COVID-19 pandemic, 83.8% of the individuals did not have postponed routine health checkups (“no, attended as planned”: 23.2%; “no, examining pending”: 58.1%; “no, other reasons”: 2.5%). More importantly, only comparing individuals attending as planned and individuals postponing checks, it is worth noting that 41% postponed routine health checkups.

Fig. 1.

Postponed routine health checkups.

Regression analysis

In Table 2 , multiple logistic regressions with postponed routine health checkups as dependent variable (0 = not postponed, 1 = postponed) were shown. Regressions showed that postponed routine health checkups since March 2020 for reasons of the COVID-19 pandemic were positively associated with the presence of chronic diseases (odds ratio [OR]: 1.68, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.15–2.47), higher affect regarding COVID-19 (OR: 1.44, 95%-CI: 1.16–1.78), and higher presumed severity of COVID-19 (OR: 1.17, 95%-CI: 1.01–1.35). By contrast, the socioeconomic variables were not associated with postponed routine health checkups.

Table 2.

Determinants of postponed routine health checkups (0 = no, not postponed; 1 = yes, postponed) due to the COVID-19 pandemic since March 2020.

| Independent variables | Postponed routine health checkups [OR (95% CI)] |

|---|---|

| Gender: female (Ref.: male) | 1.33 (0.92–1.91) |

| Age category: | |

| 30 to 49 years (Ref.: 18–29 years) | 1.40 (0.79–2.48) |

| 50 to 64 years | 0.85 (0.45–1.59) |

| 65 years and over | 0.55 (0.26–1.15) |

| Children (under 18 years): Yes (Ref.: Absence of children under 18 years) | 1.15 (0.74–1.80) |

| Education: General qualification for university entrance (Ref.: absence of qualification for university entrance) | 1.12 (0.77–1.64) |

| Town size: | |

| Medium sized town (20.001–100.000) (Ref.: municipality/small town (1–20.000)) | 1.23 (0.78–1.93) |

| Small city (100.001–500.000) | 1.32 (0.77–2.26) |

| Big city (>500.000) | 1.23 (0.74–2.03) |

| Region: East Germany (Ref.: West Germany) | 1.03 (0.59–1.82) |

| Cases/100,000 population: Above median (Ref.: below median) | 1.2 (0.81–1.81) |

| Relationship/marriage: Yes (Ref.: no partnership/marriage) | 1.12 (0.68–1.85) |

| Living situation: At least 2 individuals in the same household (Ref.: living alone) | 1.03 (0.60–1.77) |

| Migration background: Yes (Ref.: no migration background) | 0.95 (0.56–1.59) |

| Self-employment: Yes (Ref.: not self-employed) | 1.04 (0.57–1.90) |

| Chronic disease: Yes (Ref.: no chronic diseases) | 1.68∗∗ (1.15–2.47) |

| Affect regarding COVID-19 (higher values correspond to higher affect regarding COVID-19) | 1.44∗∗∗ (1.16–1.78) |

| Presumed severity of COVID-19 infection (higher values correspond to higher severity) | 1.17∗ (1.01–1.35) |

| Constant | 0.01∗∗∗ (0.00–0.03) |

| Observations | 974 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.07 |

Findings of multiple logistic regressions.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗P < 0.05, + P < 0.10.

In an additional analysis (Supplementary Table 2), logistic regressions were replaced by multinomial logistic regressions (base outcome: “Yes, postponed routine checkups”). In total, most findings remained similar. However, exclusively comparing individuals attending as planned and individuals postponing checks, it should be noted that postponed routine checkups since March 2020 for reasons of the COVID-19 pandemic were positively associated with being female (RRR (relative risk ratio): 0.64, 95%-CI: 0.41–0.98), being younger (18–29 years compared with 65 years and over, RRR: 4.38, 95%-CI: 1.89–10.19), and a higher affect regarding COVID-19 (RRR: 0.69, 95%-CI: 0.53–0.89).

Discussion

More than 16% of the individuals reported postponed routine health checkups in the past few months due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Particularly, individuals aged 30–49 years had postponed health checkups (21%). If we only compare individuals who attended as planned and individuals who postponed checkups, it should be noted that 41% postponed their visits. The probability of postponed health checkups since March 2020 for reasons of the COVID-19 pandemic was positively associated with the presence of chronic diseases, higher affect regarding COVID-19, and higher presumed severity of COVID-19, whereas the outcome measure was not associated with socioeconomic factors.

Previous studies focused on (non-)attendance of checkups. For example, a recent systematic review17 focused on the determinants of non-attendance of NHS health checks. They found that, among other things, time constraints, problems with access to general practices, and aversion to preventive medicine were key reasons for non-attendance of NHS health checks.17 While another recent study3 did not find a link between negative affect and routine health checkups in Germany, they found a link between higher positive affect and the use of routine health checkups. Furthermore, they did not find a link between chronic conditions and the use of routine health checkups. These previous findings are only partly in accordance with our findings. The differences may be mainly explained by the time. While the previous study focused on data from 2014,3 this present study focused on a period during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the previous findings are difficult to compare with our findings and should be interpreted with great caution.

With regard to the use of other healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic, one recent study among American patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases showed that avoidance of doctor's office visits and use of telehealth were common in urban areas.18 Similarly, a large decrease in pediatric emergency department visits during the COVID-19 pandemic was, for example, also observed in Germany19 or Scotland.20 On the other side, particularly in low- and middle-income countries in Asia Pacific, the healthcare systems could be overwhelmed and overstretched by the pandemic.21 For example, this can have serious consequences for maintaining cancer care.21 Moreover, disruption of essential health services (e.g. maternal or child health) have also been shown in Zimbabwe.22

We think that our findings (postponed routine health checkups during the COVID-19 pandemic associated with chronic diseases, affects regarding COVID-19, and presumed severity regarding COVID-19) may be mainly driven by the fear of being infected with COVID-19 and its potential health consequences—and this fear may be particularly pronounced among individuals with chronic diseases and among individuals with a higher perceived severity with respect to COVID-19. This is supported by the fact that very recent studies showed that individuals avoided hospital visits during the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly for reasons of being infected.13 , 23

Generally, it should be noted that postponing intended routine health checkups may be the result of balancing costs (e.g. for older individuals with multiple chronic conditions) and benefits of these routine health checkups. Therefore, for some individuals (with risk factors for severe course of COVID-19), it may be particularly important to postpone these checkups when these checkups are accompanied by a lot of social contacts (e.g. when public transport has to be used for traveling to the doctor) because this may increase the risk of getting infected with SARS-CoV-2. This in turn could have severe health consequences for individuals in bad health.

We would like to highlight some strengths and limitations of the present study. It should be acknowledged that this is the first empirical study focusing on the correlates of postponed routine health checkups during the COVID-19 pandemic. The present study used data from a nationally representative sample (community-dwelling individuals ranging from 18 to 74 years). Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that older adults aged ≥75 years should additionally be investigated in future studies. Moreover, individuals living in institutionalized settings should be examined in the upcoming studies. A pretest affirmed the high face validity of our outcome measure. All cross-sectional studies have inherent disadvantages like the difficulty to draw causal conclusions. This should be acknowledged as a limitation.

Data showed that a sizeable part (about one out of six individuals) of the population reported postponed routine health checkups due to the COVID-19 pandemic between March and July 2020. Therefore, postponed checkups should not be neglected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals at risk for postponed health checkups should be appropriately addressed. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm our findings.

In a broader sense, it may be meaningful to reshape the healthcare system.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 For instance, efforts in telemedicine or telehealth tools may contribute to addressing patient needs25 , 27 , 28—and could include some components of routine health checkups (e.g. medical recommendations for a health-promoting lifestyle).

Author statements

Acknowledgments

Germany's COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO) is a joint project of the University of Erfurt (Cornelia Betsch [PI], Lars Korn, Philipp Sprengholz, Philipp Schmid, Lisa Felgendreff, Sarah Eitze), the Robert Koch Institute (RKI; Lothar H. Wieler, Patrick Schmich), the Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA; Heidrun Thaiss, Freia De Bock), the Leibniz Centre for Psychological Information and Documentation (ZPID; Michael Bosnjak), the Science Media Center (SMC; Volker Stollorz), the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM; Michael Ramharter), and the Yale Institute for Global Health (Saad Omer).

Ethical approval

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Ethical approval for COSMO was obtained by University of Erfurt's IRB (#202000302). All procedures performed in the COSMO studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Erfurt institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

This work was supported by DFG [grant number: 3970/11-1]. Further funding was obtained via BZgA, RKI, ZPID, and the University of Erfurt [no grant numbers]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

A.H., F.d.B., and H.-H.K. contributed to conceptualization; A.H. contributed to methodology/formal analysis; A.H. contributed to writing—original draft preparation; A.H., F.d.B., B.K., and H.-H.K. contributed to writing—review and editing; H.-H.K contributed to supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the article.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.023.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Si S., Moss J.R., Sullivan T.R., Newton S.S., Stocks N.P. Effectiveness of general practice-based health checks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:e47–e53. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X676456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin (DGIM) 2018. Check-up 35 Untersuchung – eine Diskussion.http://www.dgim.de/fileadmin/user_upload/PDF/Publikationen/DGIM_check_2018.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajek A., Bock J.-O., König H.-H. The use of routine health check-ups and psychological factors—a neglected link. Evidence from a population-based study. J Publ Health. 2018;26:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajek A. The role of self-efficacy, self-esteem and optimism for using routine health check-ups in a population-based sample. A longitudinal perspective. Prev Med. 2017;105:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoebel J., Starker A., Jordan S., Richter M., Lampert T. Determinants of health check attendance in adults: findings from the cross-sectional German Health Update (GEDA) study. BMC Publ Health. 2014;14:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter M., Brand H., Rössler G. Sozioökonomische Unterschiede in der Inanspruchnahme von Früherkennungsuntersuchungen und Maßnahmen der Gesundheitsförderung in NRW. Gesundheitswesen. 2002;64:417–424. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prochazka A.V., Lundahl K., Pearson W., Oboler S.K., Anderson R.J. Support of evidence-based guidelines for the annual physical examination: a survey of primary care providers. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1347–1352. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha J.F., Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10:38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riedl D., Schüßler G. The influence of doctor-patient communication on health outcomes: a systematic review. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2017;63:131–150. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2017.63.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osterloh F. Coronavirus: krankenhäuser verschieben planbare eingriffe. Dtsch Ärztebl. 2020;117:A575–A577. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheidt-Nave C., Barnes B., Beyer A.-K., Busch M., Hapke U., Heidemann C. Versorgung von chronisch Kranken in Deutschland-Herausforderungen in Zeiten der COVID-19-Pandemie. J Health Monitor. 2020;5:2–28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajek A., De Bock F., Wieler L.H., Sprengholz P., Kretzler B., König H.-H. Perceptions of health care use in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17:9351. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazzerini M., Barbi E., Apicella A., Marchetti F., Cardinale F., Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 2020;4:e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynn R.M., Avis J.L., Lenton S., Amin-Chowdhury Z., Ladhani S.N. Delayed access to care and late presentations in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a snapshot survey of 4075 paediatricians in the UK and Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:e8. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betsch C., Wieler L.H., Habersaat K. Monitoring behavioural insights related to COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1255–1256. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30729-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Münnich R., Gabler S. Statistisches Bundesamt; Wiesbaden: 2012. 2012: stichprobenoptimierung und Schätzung in Zensus 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harte E., MacLure C., Martin A., Saunders C.L., Meads C., Walter F.M. Reasons why people do not attend NHS Health Checks: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68:e28–e35. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X693929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michael George, Shilpa Venkatachalam, Shubhasree Banerjee, Joshua F. Baker, Peter A. Merkel, Kelly Gavigan, David Curtis, Maria I. Danila, Jeffrey R. Curtis, W Benjamin Nowell. Concerns, healthcare use, and treatment interruptions in patients with common autoimmune rheumatic diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Rheumatol. 2020 doi: 10.3899/jrheum.201017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dopfer C., Wetzke M., Zychlinsky Scharff A., Mueller F., Dressler F., Baumann U. COVID-19 related reduction in pediatric emergency healthcare utilization - a concerning trend. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:427. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02303-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams T.C., MacRae C., Swann O.V., Haseeb H., Cunningham S., Davies P. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric healthcare use and severe disease: a retrospective national cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2021 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Guzman R., Malik M. Dual challenge of cancer and COVID-19: impact on health care and socioeconomic systems in Asia Pacific. JCO Global Oncol. 2020;6:906–912. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murewanhema G., Makurumidze R. Essential health services delivery in Zimbabwe during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives and recommendations. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35:143. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.143.25367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fricke A. 2020. Versorgungsrisiko Corona: selbst Patienten mit Schlaganfall bleiben zu Hause.https://www.aerztezeitung.de/Politik/Selbst-Patienten-mit-Schlaganfall-bleiben-zu-Hause-408354.html [2nd September 2020]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danhieux K., Buffel V., Pairon A., Benkheil A., Remmen R., Wouters E. The impact of COVID-19 on chronic care according to providers: a qualitative study among primary care practices in Belgium. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franzosa E., Gorbenko K., Brody A.A., Leff B., Ritchie C.S., Kinosian B. “At home, with care”: lessons from New York city home-based primary care practices managing COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:300–306. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goh Y.S., Ow Yong Q.Y.J., Chen T.H.M., Ho S.H.C., Chee Y.I.C., Chee T.T. The Impact of COVID-19 on nurses working in a University Health System in Singapore: a qualitative descriptive study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1111/inm.12826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shalini Shah M., Sudhir Diwan M., Lynn Kohan M., David Rosenblum M., Christopher Gharibo M., Amol Soin M. The technological impact of COVID-19 on the future of education and health care delivery. Pain Physician. 2020;23:S367–S380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golinelli D., Boetto E., Carullo G., Nuzzolese A.G., Landini M.P., Fantini M.P. How the COVID-19 pandemic favored the adoption of digital technologies in healthcare: a systematic review of early scientific literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;21:e22280. doi: 10.2196/22280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.