Sororin plays a noncanonical role in driving meiotic resumption and progression through meiosis I in mammalian oocytes.

Abstract

During the S phase of mitosis, Sororin is recruited by acetylated Smc3 and stabilizes sister chromatid cohesion by counteracting the Wapl-Pds5 interaction. Thereafter, Sororin is phosphorylated during prophase and translocated to the cytoplasm, where its function remains poorly understood. Here, we report that Sororin acts as a regulator of meiotic G2-M transition and spindle assembly in mammalian oocytes. Sororin is present in the nucleus of GV oocytes and becomes associated with the spindle apparatus during meiosis I in mice. Depletion of Sororin causes failure of GVBD due to inactivation of Cdk1 and defective spindle assembly because of reduced levels of Cyclin B2. We validate Sororin interactions with Cyclin B2 that protects it from destruction by APCCdh1, which drives M phase entry and bipolar spindle formation. Notably, the meiotic functions of Sororin are conserved among mammals. Together, our findings provide novel insights into the noncanonical role of Sororin in the resumption of meiosis and progression through meiosis I in mammalian oocytes.

INTRODUCTION

Cohesin is a ring-shaped protein complex involved in diverse biological events, including sister chromatid cohesion, chromosome segregation, centriole engagement, DNA damage repair, transcriptional regulation, and chromatin architecture organization (1–9). In eukaryotic cells, the cohesin complex is composed of Smc1, Smc3, Scc1, and SA/STAG subunits and is regulated by several accessory factors (1). Among them, Sororin acts as a stabilizing factor to maintain chromosome cohesion. During S phase, acetyltransferase Esco2 acetylates Smc3 to establish cohesion and recruits Sororin to stabilize cohesin on sister chromosomes by dissociating the release factor Wapl from the adaptor Pds5 (10–12). Esco1-dependent modification of Smc3 almost exclusively regulates the noncohesive activities of cohesin, such as DNA repair, transcriptional control, chromosome loop formation, and/or stabilization (10). By prophase, Aurora B and Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) phosphorylate Sororin to destabilize its interaction with Pds5, resulting in the formation of Wapl-Pds5 heterodimers and removal of cohesin from chromosome arms (12–15). Subsequently, Sororin appears in the cytoplasm during the G2-M transition, and its presumptive function remains elusive (16).

In Sororin-depleted HeLa cells, the distance between sister chromatids increases twofold compared to controls and chromosomes fail to congress (12). In vivo, Sororin is essential for early mammalian development and homozygous knockout mice are embryonic lethal (17). Beginning in prophase I and extending to anaphase II of male meiosis, Sororin complexes with the central region of the synaptonemal complex in a SYCP1-dependent, but cohesin-independent, manner (18). Meiosis is characterized by two rounds of chromosome segregation after a single round of DNA replication to generate haploid gametes from diploid precursors. During meiosis I, homologs segregate to reduce the chromosome number and ensure the inheritance of gametes (19). The role of Sororin during meiosis I in oocytes has not been elucidated.

In the present study, we investigate the subcellular distribution, expression, and function of Sororin during female meiosis I in mice. We observe that Sororin is present in the nucleus of germinal vesicle (GV) oocytes where it drives the G2-M transition and then translocates to the spindle apparatus to regulate spindle assembly during meiosis. We document that the meiotic functions of Sororin are affected by Cyclin B2 stability, which is conserved among mammals.

RESULTS

Subcellular localization and expression of Sororin during mouse oocyte meiosis

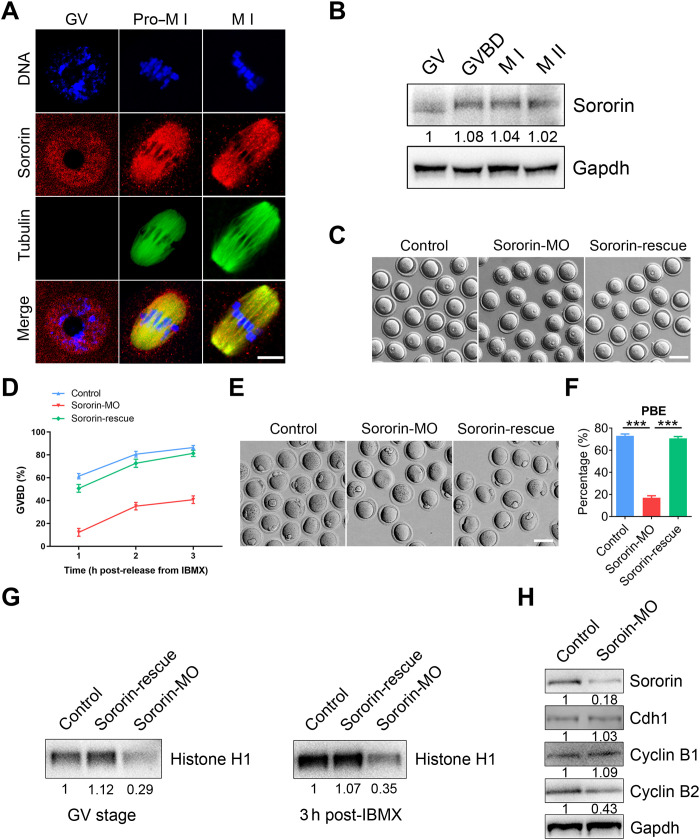

To explore the potential role of Sororin in oocyte meiosis, we first determined its subcellular localization at different developmental stages during mouse oocyte maturation. Immunofluorescence and confocal imaging showed that Sororin was predominantly present in the nucleus of GV oocytes (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A). After GV breakdown (GVBD), Sororin in the cytoplasm colocalized with α-tubulin and accumulated on the meiotic spindle at prometaphase I (pro-M I) and metaphase I (M I) (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A). This localization was confirmed independently using a different antibody for Sororin and by the localization of exogenous Sororin–green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressed in oocytes (fig. S1, B and C). In addition, costaining with antibodies for calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia (CREST) or γ-tubulin documented that Sororin was absent on chromosomes or kinetochores after GVBD (fig. S1D) but was present in microtubule-organizing centers (fig. S1E). Sororin expression remained constant throughout the progressive GV, GVBD, M I, and M II stages of meiosis (Fig. 1B). Together, the distinct localization and expression patterns of Sororin in oocytes compared to mitotic cells suggest that it might play a unique role during meiosis.

Fig. 1. Sororin promotes meiotic resumption in mouse oocytes.

(A) Representative images of Sororin localization in oocytes. Mouse oocytes at different developmental stages were immunostained with Sororin and α-tubulin antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Protein levels of Sororin during oocyte meiosis corresponding to GV (0 hours), GVBD (4 hours), M I (8 hours), and M II (12 hours) stages were examined by immunoblots. The blots were probed with Sororin and Gapdh antibodies. (C) Representative images of the occurrence of GVBD in control, Sororin-MO, and Sororin-rescue (Sororin-MO + Sororin-cRNA) oocytes at 3 hours following release from IBMX. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) The incidence of GVBD at 1, 2, and 3 hours post-IBMX release was quantified in control (n = 155), Sororin-MO (n = 157), and Sororin-rescue (n = 150) oocytes. (E) Representative images of PBE in control, Sororin-MO, and Sororin-rescue oocytes at 10 hours after GVBD. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) PBE rate was quantified in control (n = 175), Sororin-MO (n = 177), and Sororin-rescue (n = 181) oocytes. (G) Histone H1 kinase activity at stages of GV and 3 hours post-IBMX release was detected in control, Sororin-MO, and Sororin-rescue oocytes. (H) Protein levels of G2-M transition regulators were assessed by immunoblots in control and Sororin-depleted oocytes. The blots were probed with Sororin, Cdh1, Cyclin B1, Cyclin B2, and Gapdh antibodies. Data of (D) and (F) were presented as mean value (mean ± SEM) of at least three independent biological replicates. ***P < 0.001.

Sororin is required for Cdk1 activity and G2-M transition in oocytes

To investigate the function of Sororin, we used morpholino (MO) to reduce Sororin protein levels in oocytes. On the basis of immunoblotting and immunofluorescence, up to 90% of the protein was depleted in Sororin-targeted MO-injected GV-intact oocytes (fig. S2). Almost half of the Sororin-depleted oocytes failed to undergo GVBD (Fig. 1, C and D), confirming the role of Sororin in the G2-M transition. In addition, Sororin depletion led to a substantial decrease in the first polar body extrusion (PBE) (Fig. 1, E and F), indicating that Sororin is essential for oocyte meiotic progression. Notably, Sororin-depleted oocytes that did not extrude polar bodies after in vitro maturation arrested at M I in a spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC)–dependent manner (fig. S3). To exclude off-target effects, we expressed exogenous Sororin in MO-injected oocytes (rescue oocytes) to restore the frequency of GVBD and PBE to control levels (Fig. 1, C and D).

Because G2-M transition failure is associated with impaired Cdk1 activity, we used a histone H1 kinase assay to measure the enzymatic activity. The activity was markedly reduced in Sororin-depleted oocytes at GV and pro–M I stages but was restored in Sororin-rescue oocytes (Fig. 1G). Because Cdk1 is activated by the binding of its regulatory subunit Cyclin B1 (20–22), changes in the levels of Cyclin B1 and/or the regulatory protein Cdh1 of its E3 ubiquitin ligase APCCdh1 could inhibit entry into M phase (23, 24). Therefore, we evaluated the protein levels of Cyclin B1 and Cdh1 in Sororin-depleted oocytes via immunoblotting but did not observe any perturbation (Fig. 1H), confirming that the decreased Cdk1 activity was independent of the canonical APCCdh1–Cyclin B1 pathway. It has been reported that Cyclin B2 can compensate for Cyclin B1 for Cdk1 activation during the meiotic G2-M transition (25–28), and we observed that Cyclin B2 was prominently decreased after Sororin depletion (Fig. 1H). Thus, we conclude that Sororin is required for Cdk1 activation in oocytes and may regulate Cdk1 activity and G2-M transition via Cyclin B2.

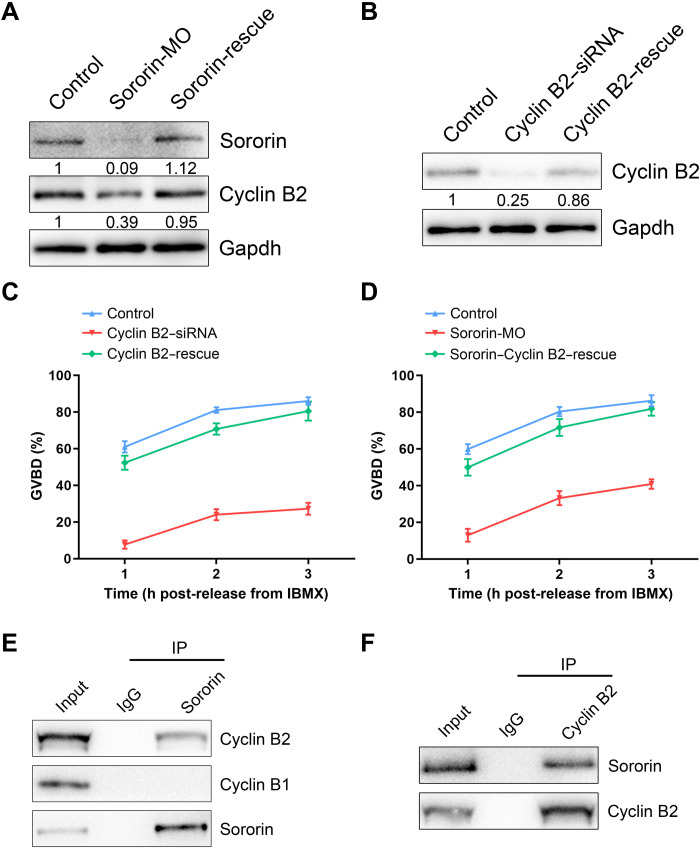

Sororin associates with Cyclin B2 to maintain its protein level

To confirm the effect of Sororin on Cyclin B2, we determined that protein levels were restored in Sororin-rescue oocytes (Fig. 2A). Cyclin B2 was profoundly depleted after microinjection of Cyclin B2–targeted small interfering RNA (siRNA) but could be rescued by Cyclin B2 complementary RNA (cRNA) in Cyclin B2–rescue oocytes (Fig. 2B). Only ~27% of oocytes underwent GVBD after depletion of Cyclin B2 (Fig. 2C), which corresponded to a similar impairment in Sororin-depleted oocytes. The normality of Cyclin B2–rescue oocytes (Fig. 2C) confirmed the role of Cyclin B2 during G2-M transition. We further investigated whether restoration of Cyclin B2 levels could counteract the G2 arrest caused by Sororin depletion. As anticipated, we observed that the frequency of GVBD was substantially higher in Cyclin B2–rescue oocytes than in Sororin-depleted oocytes (Fig. 2D). Thus, we conclude that Cyclin B2 mediates the action of Sororin on the G2-M transition in oocytes.

Fig. 2. Sororin interacts with Cyclin B2 and maintains its protein level to participate in the G2-M transition.

(A) Protein levels of Cyclin B2 in control, Sororin-MO, and Sororin-rescue GV oocytes. The blots were probed with Sororin, Cyclin B2, and Gapdh antibodies. (B) Protein levels of Cyclin B2 in control, Cyclin B2–siRNA, and Cyclin B2–rescue (Cyclin B2–siRNA + Cyclin B2–cRNA) GV oocytes. The blots were probed with Cyclin B2 and Gapdh antibodies. (C) The incidence of GVBD at 1, 2, and 3 hours post-IBMX release was quantified in control (n = 85), Cyclin B2–siRNA (n = 92), and Cyclin B2–rescue (n = 82) oocytes. (D) The incidence of GVBD at 1, 2, and 3 hours post-IBMX release was quantified in control (n = 87), Sororin-MO (n = 93), and Sororin–Cyclin B2–rescue (Sororin-MO + Cyclin B2–cRNA; n = 88) oocytes. (E) Co-IP was performed with Sororin antibody in GV oocytes. The immunoblots of protein precipitants were probed with Sororin, Cyclin B1, and Cyclin B2 antibodies. (F) Co-IP was performed with Cyclin B2 antibody in GV oocytes. The immunoblots of protein precipitants were probed with Sororin and Cyclin B2 antibodies. Data of (C) and (D) were presented as mean value (mean ± SEM) of at least three independent biological replicates.

Immunoblots after co-immunoprecipitation (IP) with an antibody to Sororin documented that Cyclin B2 was present in the protein precipitate (Fig. 2E) as was Sororin, but not Cyclin B1 (Fig. 2E). In reciprocal experiments, Sororin was observed in the protein precipitate after treatment with Cyclin B2 antibody (Fig. 2F), confirming that Sororin interacts with Cyclin B2 in oocytes.

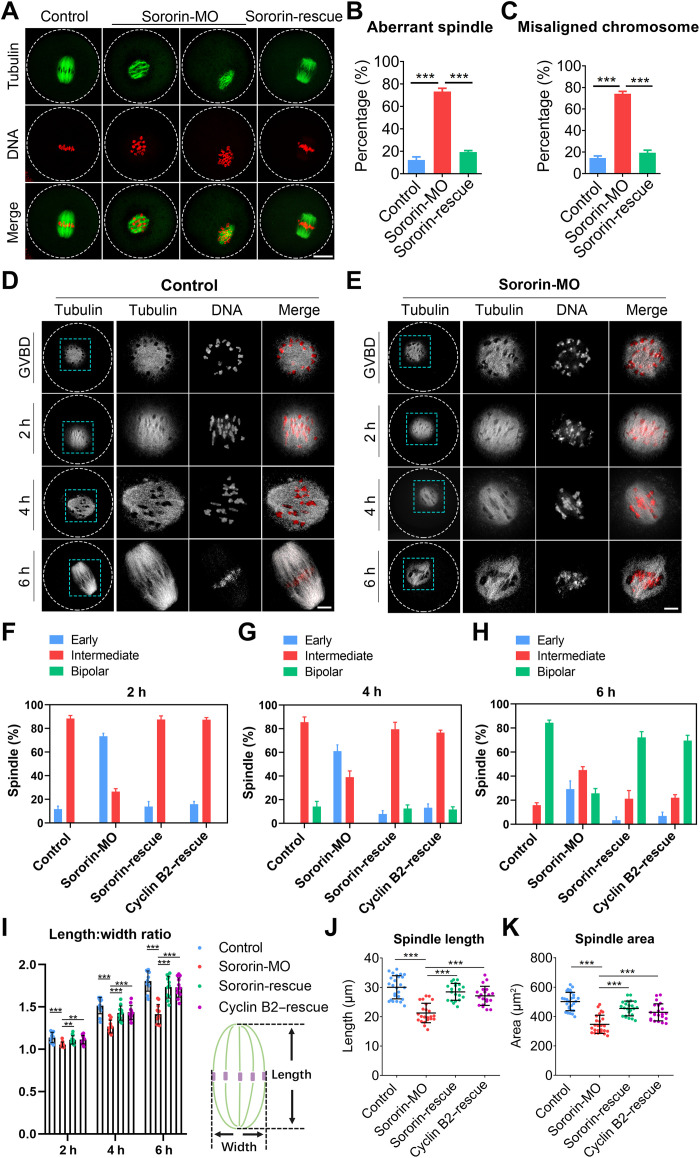

Sororin is indispensable for meiotic spindle assembly

Because of strong immunofluorescence on the spindle after GVBD, we hypothesized that Sororin might play a regulatory role in the spindle assembly during meiosis. Therefore, immunostaining of M I oocytes was used to observed spindle/chromosome structures in control and Sororin-depleted oocytes. In controls, more than 85% of oocytes had typical barrel-shaped spindles containing well-aligned chromosomes at the equatorial plate (Fig. 3, A to C). In contrast, depletion of Sororin resulted in ~70% aberrant spindles and misaligned chromosomes (Fig. 3, A to C) with increased width of the chromosome plate (fig. S4, A and B). These spindle and chromosome defects were phenocopied by RNA interference (RNAi)–mediated knockdown of Sororin and could be recovered by expression of exogenous Sororin (fig. S5).

Fig. 3. Sororin controls meiotic spindle assembly via Cyclin B in mouse oocytes.

(A) Representative images of spindle assembly and chromosome alignment in control, Sororin-MO, and Sororin-rescue oocytes. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B and C) The rates of abnormal spindles and misaligned chromosomes were quantified in control (n = 90), Sororin-MO (n = 89), and Sororin-rescue (n = 67) oocytes. (D and E) Representative images of spindle assembly at different time points in control and Sororin-MO oocytes. Scale bars, 5 μm. (F to H) The proportion of different types of spindles in control (n = 69, 62, and 64), Sororin-MO (n = 64, 59, and 62), Sororin-rescue (n = 65, 64, and 61), and Cyclin B2–rescue (Sororin-MO + Cyclin B2–cRNA; n = 63, 61, and 58) oocytes at 2, 4, and 6 hours after GVBD. (I) The ratio of spindle length to width during spindle assembly was calculated in control (n = 37), Sororin-MO (n = 38), Sororin-rescue (n = 36), and Cyclin B2–rescue (n = 36) oocytes. (J and K) The spindle length and area were measured in control (n = 26 and 29), Sororin-MO (n = 23 and 25), Sororin-rescue (n = 20 and 23), and Cyclin B2–rescue (n = 20 and 22) oocytes at 6 hours after GVBD. Data were presented as mean percentage (mean ± SEM) or mean value (mean ± SD) of at least three independent biological replicates. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The elevated incidence of misaligned chromosomes in Sororin-depleted oocytes implies impairment of kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Therefore, unattached microtubules were depolymerized by cold and very few cold-stable microtubules were observed in Sororin-depleted oocytes compared to controls (fig. S4, C and D). To determine whether spindle defects and chromosome misalignment in Sororin-depleted oocytes were caused by compromised chromosome cohesion, we assessed the binding of cohesin to chromosomes by immunostaining for Rec8, a meiotic-specific cohesin subunit. Rec8 was not affected by Sororin depletion, and there was no change in the distance between homologs (fig. S6). Thus, although Sororin is important for spindle assembly, it has no apparent role in chromosome cohesion during meiosis I.

Sororin modulates spindle assembly via Cyclin B2

Because Cyclin B2 has been implicated in bipolar spindle formation during oocyte meiosis (25, 28), we investigated whether the regulation of Sororin in spindle assembly is mediated by Cyclin B2. We monitored spindle organization status during meiosis I at several critical time points after Sororin depletion. The early stage of spindle assembly after GVBD was characterized by a microtubule ball with clumped chromosomes in both control and Sororin-depleted oocytes (Fig. 3, D and E). At 4 hours after GVBD, the spindle lengthened to form an intermediate structure with polarity in control oocytes but persisted in a spherical state in Sororin-depleted oocytes (Fig. 3, D and E). At 6 hours after GVBD, control oocytes formed a bipolar barrel-shaped spindle, whereas Sororin-depleted oocytes contained intermediate spindles with scattered chromosomes (Fig. 3, D and E). These observations were confirmed by the quantification of three typical spindle morphologies during M I spindle assembly (early, intermediate, and bipolar) at different time points (Fig. 3, F to H, and fig. S7). In addition, we found that the length-to-width ratio of the spindle was significantly increased with the progression of spindle formation in controls compared to the relative uniformity in Sororin-depleted oocytes (Fig. 3I). The spindle length and area in oocytes at 6 hours after GVBD were considerably reduced in Sororin-depleted oocytes (Fig. 3, J and K). Notably, all these spindle defects in Sororin-depleted oocytes were recovered in varying degrees after the expression of exogenous Sororin or Cyclin B2 (Fig. 3, F to K). Collectively, these results indicate that Cyclin B2 is the downstream effector of Sororin in oocyte meiotic spindle assembly.

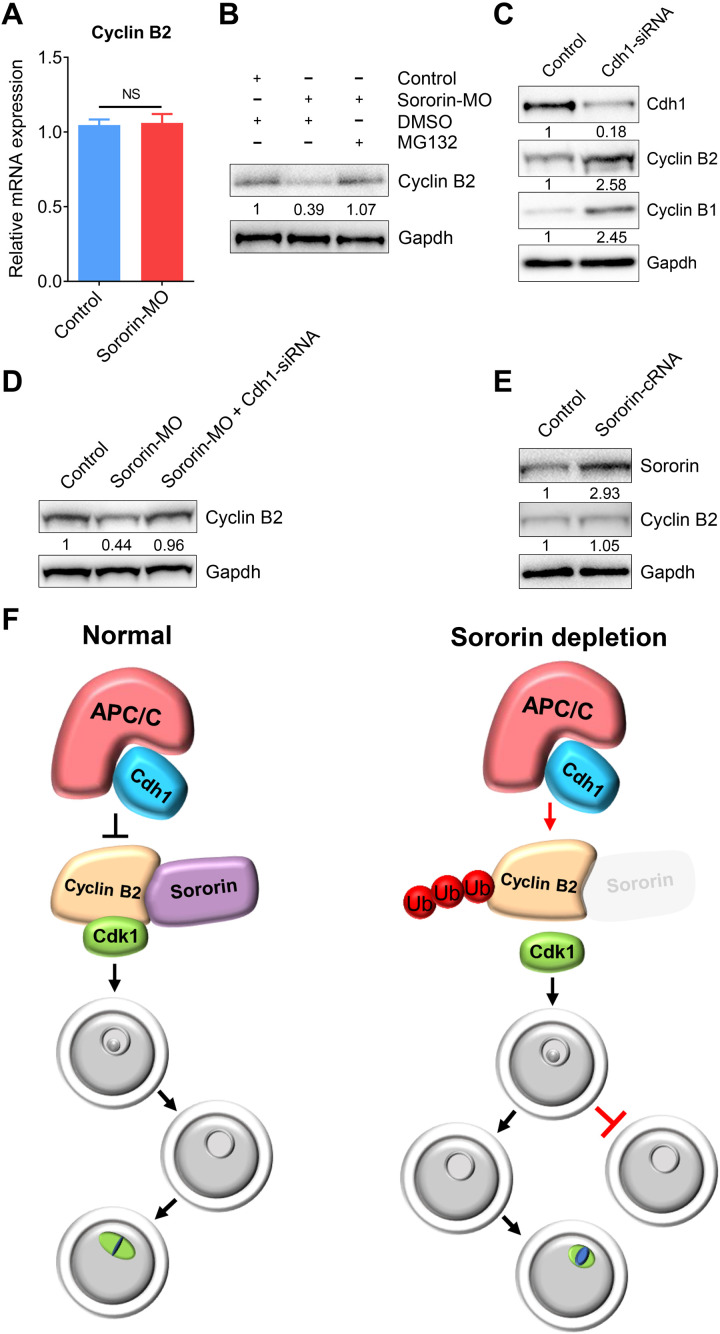

Sororin protects Cyclin B2 from APCCdh1-mediated degradation

After Sororin depletion, mRNA levels of Cyclin B2 were not affected (Fig. 4A), but ubiquitination and subsequent degradation were perturbed. Treatment of Sororin-depleted oocytes with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 markedly increased Cyclin B2 levels in immunoblots (Fig. 4B). Cyclin B2 is a known substrate of the E3 ubiquitin ligase APCCdh1 in oocytes during prophase and early prometaphase (25). After treatment with RNAi to deplete Cdh1, elevated levels of Cyclin B1 and Cyclin B2 were observed in oocytes (Fig. 4C), and protein levels of Cyclin B2 were restored in Sororin-depleted oocytes (Fig. 4D). However, overexpression of Sororin in oocytes did not increase the abundance of Cyclin B2 (Fig. 4E), revealing that endogenous Sororin is sufficient to maintain the Cyclin B2 level. In other words, redundant Sororin could not break the balance of APCCdh1-mediated protein degradation of Cyclin B2.

Fig. 4. Sororin protects Cyclin B2 from APCCdh1-mediated degradation.

(A) mRNA levels of Cyclin B2 were determined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in control (n = 90) and Sororin-MO (n = 90) oocytes. Data were presented as mean value (mean ± SEM) of at least three independent biological replicates. NS, not significant. (B) Protein levels of Cyclin B2 in control, Sororin-MO, and Sororin-MO + MG132 oocytes. The blots were probed with Cyclin B2 and Gapdh antibodies. (C) Protein levels of Cyclin B1 and Cyclin B2 in control and Cdh1-siRNA oocytes. The blots were probed with Cdh1, Cyclin B1, Cyclin B2, and Gapdh antibodies. (D) Protein levels of Cyclin B2 in control, Sororin-MO, and Sororin-MO + Sororin-MO + Cdh1-siRNA oocytes. The blots were probed with Cyclin B2 and Gapdh antibodies. (E) Protein levels of Cyclin B2 in control and Sororin-overexpressed oocytes. The blots were probed with Sororin, Cyclin B2, and Gapdh antibodies. (F) Working model for the functions of Sororin during G2-M transition and spindle assembly in mammalian oocytes. In normal oocytes, Sororin binds to Cyclin B2 to protect it against APCCdh1-mediated degradation and thereby drives the G2-M transition and spindle assembly. However, in oocytes depleted of Sororin, either G2-M transition is inhibited or the spindle assembly during meiosis I is compromised due to the degradation of Cyclin B2.

The noncanonical functions of Sororin in oocyte meiosis are conserved in mammals

To determine whether the noncanonical roles of Sororin in oocytes were conserved among mammals, we examined the G2-M transition and spindle assembly in porcine oocytes following Sororin depletion by microinjection of siRNA. Consistent with the data in mice, we found that depletion of Sororin in porcine oocytes also led to a substantial decrease in Cyclin B2 protein levels (fig. S8). Moreover, the occurrence of GVBD was decreased and the incidence of spindle/chromosome abnormalities was increased in Sororin-depleted porcine oocytes (fig. S9). Together, we demonstrate that Sororin exerts unique functions in the prophase I arrest and prometaphase progression in at least two mammalian species.

DISCUSSION

Meiosis involves one round of DNA replication followed by two successive nuclear and cellular divisions (meiosis I and meiosis II) (19, 29). Meiosis I is unique because only homologous chromosomes (bivalent) segregate during this process, whereas sister chromatids remain together. Determining how this unusual chromosome segregation occurs is central to understanding germ cell development (30). Our previous studies have documented that cohesin regulators Esco1, Esco2, and Wapl participate in spindle assembly and checkpoint control. They ensure faithful homologous chromosome segregation during meiosis I independent of their canonical roles in chromosome cohesion (31–33). However, the role of Sororin as a cohesin stabilizer during meiosis remains poorly understood.

Our current findings show that the subcellular localization and protein expression patterns of Sororin during oocyte meiosis are different from those during mitosis. In mitotic cells, Sororin accumulates in the nucleus during interphase and translocates to the cytoplasm following nuclear envelope breakdown (12). The protein expression level of Sororin increases from the G1 to G2 phase but considerably decreases by the end of mitosis (12). In mouse oocytes, however, Sororin concentrates from the nucleus to the spindle apparatus after GVBD and is present throughout meiosis. This unique localization and expression dynamics of Sororin in oocytes imply that it may have distinct or additional functions in meiosis.

Unexpectedly, we discovered that depletion of Sororin in oocytes impedes the G2-M transition due to compromised Cdk1 activity. Unexpectedly, Cyclin B1 (a Cdk1 activator subunit) and its E3 ubiquitin ligase APCCdh1 were not affected by Sororin depletion, although both have been reported to participate in the regulation of meiotic G2-M transition (20, 21). However, Cyclin B2, another key Cdk1-activating subunit, can compensate for Cyclin B1 in regulating Cdk1 activity to resume oocyte meiosis (25–28). Our data indicate that Sororin interacts with Cyclin B2 and is required to preserve its protein levels in oocytes. Notably, the compromised G2-M transition caused by Sororin depletion was restored by expressing exogenous Cyclin B2. In contrast, Sororin depletion during mitosis leads to arrest and failure of sister chromatid cohesion (16).

Our results indicate that Sororin is essential for meiotic spindle assembly during oocyte meiosis I. This is consistent with a previous report that Cyclin B2 plays a role in bipolar spindle formation in mouse oocytes (25, 28). The rescue of spindle defects in Sororin-depleted oocytes by expression of exogenous Cyclin B2 confirms that Sororin is involved in Cyclin B2–mediated spindle assembly. In contrast, Sororin-depleted HeLa cells show relatively normal spindle formation, although chromosomes fail to congress (16).

Last, we demonstrate that Sororin protects Cyclin B2 from APCCdh1-mediated proteasomal degradation in oocytes. Both inhibition of the proteasome by MG132 and depletion of Cdh1 increased protein levels of Cyclin B2 in Sororin-depleted oocytes. Moreover, we demonstrate that the nonconventional functions of Sororin during oocyte meiosis are conserved among at least two mammalian species. Notably, Hec1/Ndc80 has also been reported to function in oocyte meiotic resumption and meiotic spindle assembly by stabilizing Cyclin B2 from APCCdh1-dependent degradation (25). The relationship between Sororin, Hec1, and Cyclin B2 requires further investigation.

In summary, we document that Sororin, a cohesin stabilizer, orchestrates meiotic G2-M transition and spindle assembly by maintaining Cyclin B2 levels in oocytes. Loss of Sororin results in either meiotic prophase I arrest or spindle defects due to APCCdh1-mediated degradation of Cyclin B2 (Fig. 4F). Our findings uncover the unique roles of Sororin in driving the resumption of meiosis and progression through meiosis I to produce fertilization-competent oocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Six- to 8-week-old female ICR mice were used in all experiments, which were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University, China and were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Oocyte collection and culture

Female ICR mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Fully grown oocytes arrested at prophase of meiosis I were collected from ovaries in M2 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Only those immature oocytes displaying a GV were further cultured in M16 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) under liquid mineral oil at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

MO knockdown

Sororin-targeting MO antisense oligo (5′-CTACTCAGGCTCGCGCCAAC-3′; Gene Tools, Philomath, OR, USA) was diluted with water to provide a working concentration of 1 mM, and then approximately 5 to 10 pl of oligo were microinjected into the cytoplasm of fully grown GV oocytes using a Narishige microinjector (Tokyo, Japan). A nontargeting MO oligo (5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′) was injected as a control. To facilitate MO-mediated inhibition of mRNA translation, oocytes were arrested at GV stage in M16 medium containing 50 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) for 20 hours and then cultured in IBMX-free M16 medium for further experiments.

siRNA knockdown

Sororin-targeting siRNA oligo (antisense sequence: 5′-ACUAUCUGGAACCAAGUCCTT-3′; GenePharma, Shanghai, China), Cyclin B2–targeting siRNA oligo (antisense sequence: 5′-AAGAAGUGUGGAUUAAUGGTT-3′), or Cdh1-targeting siRNA oligo (antisense sequence: 5′-AUUGCCAUCAUCUGGACUCTT-3′) was diluted with water to provide a working concentration of 25 μM, and then approximately 5 to 10 pl of oligo were microinjected into the cytoplasm of fully grown mouse GV oocytes using a Narishige microinjector. A nontargeting siRNA oligo (antisense sequence: 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′) was injected as a control. To facilitate the degradation of mRNA by siRNA, mouse oocytes were arrested at GV stage in M16 medium containing 50 μM IBMX for 24 hours and then transferred to IBMX-free M16 medium to resume the meiosis for subsequent experiments. Knockdown of Sororin in porcine oocytes was achieved via microinjection of 50 μM Sororin-targeting siRNA oligo (antisense sequence: 5′-ACAUUUCCAAGUCUCUGGCTT-3′). A nontargeting siRNA oligo (antisense sequence: 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′) was injected as a control. Oocytes were arrested at GV stage in TCM-199 medium containing 50 μM IBMX for 24 hours and then transferred to IBMX-free TCM-199 medium to resume the meiosis for further experiments.

cRNA construct and in vitro transcription

Sororin or Cyclin B2 complementary DNA (cDNA) was subcloned into pcDNA3.1/GFP or pcDNA3.1/HA. Mutant Sororin with four silent third-codon point mutations in the sequence targeted by the MO provided a MO-resistant construct. Mutant Cyclin B2 with three silent third-codon point mutations in the sequence targeted by the seed region of siRNA antisense strand provided a siRNA-resistant construct. Capped cRNA was synthesized from linearized plasmid using T7 mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and purified with a MEGAclear kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Typically, 10 to 12 pl of cRNA (0.5 to 1.0 μg/μl) were injected into oocytes and then arrested at GV stage in M16 medium containing 200 μM IBMX for 4 hours to allow translation before transfer into IBMX-free M16 medium for subsequent studies.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Oocytes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) for 30 min and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min (mouse oocytes) or 1% Triton X-100 for 1 hour (porcine oocytes) at room temperature. Oocytes were then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin–supplemented PBS for 1 hour and incubated with Sororin (1:100; Abcam, ab192237; ABclonal, A16590), α-tubulin–FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) (1:300; Sigma-Aldrich, F2168), γ-tubulin (1:100; Abcam, ab179503), CREST (1:200; Antibodies Incorporated, CA95617), BubR1 (1:100; Abcam, ab28193), or Rec8 (1:100; Abcam, ab38372) antibodies at 4°C overnight. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 (PBST), oocytes were incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Oocytes were then counterstained with propidium iodide or Hoechst (10 μg/ml) for 10 min. Last, oocytes were mounted on glass slides and imaged with a confocal microscope (LSM 900 META, Zeiss, Germany).

IP and immunoblotting

IP was performed with 800 to 1000 oocytes according to instructions in the ProFound Mammalian Co-Immunoprecipitation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For immunoblots, oocytes were lysed in 4× lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing protease inhibitor, separated on 10% bis-tris precast gels, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The blots were further blocked in tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) containing 5% low fat dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature and then incubated with Sororin (1:1000; Abcam, ab192237), Cyclin B2 (1:1000; R&D Systems, AF6004-SP), Cdh1 (1:1000; ProteinTech, 16368-1-AP), Cyclin B1 (1:1000; Abcam, ab32053), or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) (1:5000; Cell Signaling Technology, 2118) antibodies at 4°C overnight. After washing in TBST, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Chemiluminescence was detected with ECL Plus (GE, Piscataway, NJ, USA), and protein bands were acquired by the Tanon 3900 Chemiluminescence Imaging System (Tanon, Beijing, China).

Histone H1 kinase assay

Oocytes were lysed in 3 μl of lysis buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor] on ice for 20 min before adding 6 μl of kinase assay buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 2.5 mM EGTA, and 150 μM adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP)] supplemented with 3 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) per sample. Histone H1 (0.5 μg per sample; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used as a substrate. Kinase reactions were incubated at 30°C for 30 min, denatured, and analyzed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gel was fixed and dried before being exposed and scanned to detect incorporation of [γ-32P]ATP into the substrate using a phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

Statistical analysis

All percentages or values from at least three biological replicates were expressed as mean ± SEM or mean ± SD, and the number of oocytes was labeled in parentheses as (n). Data were analyzed by paired-samples t test, which was provided by GraphPad Prism 5 statistical software. The level of significance was accepted as P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31822053, 32070836, and 31900592) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20190526). Author contributions: B.X. designed the research. C.Z., X.Z., Y.M., Y.Z., and Y.L. performed the experiments. C.Z. and B.X. analyzed the data. C.Z. and B.X. wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S10

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Xiong B., Gerton J. L., Regulators of the cohesin network. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 131–153 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorsett D., The many roles of cohesin in Drosophila gene transcription. Trends Genet. 35, 542–551 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishiyama T., Cohesion and cohesin-dependent chromatin organization. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 58, 8–14 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowley M. J., Corces V. G., Organizational principles of 3D genome architecture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 789–800 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schockel L., Mockel M., Mayer B., Boos D., Stemmann O., Cleavage of cohesin rings coordinates the separation of centrioles and chromatids. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 966–972 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasmyth K., Haering C. H., Cohesin: Its roles and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 525–558 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seitan V. C., Merkenschlager M., Cohesin and chromatin organisation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 93–100 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yatskevich S., Rhodes J., Nasmyth K., Organization of chromosomal DNA by SMC complexes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 53, 445–482 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uhlmann F., SMC complexes: From DNA to chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 399–412 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alomer R. M., da Silva E. M. L., Chen J., Piekarz K. M., McDonald K., Sansam C. G., Sansam C. L., Rankin S., Esco1 and Esco2 regulate distinct cohesin functions during cell cycle progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 9906–9911 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou F., Zou H., Two human orthologues of Eco1/Ctf7 acetyltransferases are both required for proper sister-chromatid cohesion. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3908–3918 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishiyama T., Ladurner R., Schmitz J., Kreidl E., Schleiffer A., Bhaskara V., Bando M., Shirahige K., Hyman A. A., Mechtler K., Peters J. M., Sororin mediates sister chromatid cohesion by antagonizing Wapl. Cell 143, 737–749 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gimenez-Abian J. F., Sumara I., Hirota T., Hauf S., Gerlich D., de la Torre C., Ellenberg J., Peters J. M., Regulation of sister chromatid cohesion between chromosome arms. Curr. Biol. 14, 1187–1193 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiyama T., Sykora M. M., Huis in ’t Veld P. J., Mechtler K., Peters J.-M., Aurora B and Cdk1 mediate Wapl activation and release of acetylated cohesin from chromosomes by phosphorylating Sororin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 13404–13409 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kueng S., Hegemann B., Peters B. H., Lipp J. J., Schleiffer A., Mechtler K., Peters J. M., Wapl controls the dynamic association of cohesin with chromatin. Cell 127, 955–967 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rankin S., Ayad N. G., Kirschner M. W., Sororin, a substrate of the anaphase-promoting complex, is required for sister chromatid cohesion in vertebrates. Mol. Cell 18, 185–200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladurner R., Kreidl E., Ivanov M. P., Ekker H., Idarraga-Amado M. H., Busslinger G. A., Wutz G., Cisneros D. A., Peters J. M., Sororin actively maintains sister chromatid cohesion. EMBO J. 35, 635–653 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez R., Felipe-Medina N., Ruiz-Torres M., Berenguer I., Viera A., Perez S., Barbero J. L., Llano E., Fukuda T., Alsheimer M., Pendas A. M., Losada A., Suja J. A., Sororin loads to the synaptonemal complex central region independently of meiotic cohesin complexes. EMBO Rep. 17, 695–707 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petronczki M., Siomos M. F., Nasmyth K., Un Ménage à Quatre. Cell 112, 423–440 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt J. E., Weaver J., Jones K. T., Spatial regulation of APCCdh1-induced cyclin B1 degradation maintains G2 arrest in mouse oocytes. Development 137, 1297–1304 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reis A., Chang H. Y., Levasseur M., Jones K. T., APCcdh1 activity in mouse oocytes prevents entry into the first meiotic division. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 539–540 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geley S., Kramer E., Gieffers C., Gannon J., Peters J. M., Hunt T., Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome-dependent proteolysis of human cyclin A starts at the beginning of mitosis and is not subject to the spindle assembly checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 153, 137–148 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marangos P., Carroll J., Securin regulates entry into M-phase by modulating the stability of cyclin B. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 445–451 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homer H., Gui L., Carroll J., A spindle assembly checkpoint protein functions in prophase I arrest and prometaphase progression. Science 326, 991–994 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gui L., Homer H., Hec1-dependent cyclin B2 stabilization regulates the G2-M transition and early prometaphase in mouse oocytes. Dev. Cell 25, 43–54 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homer H., The APC/C in female mammalian meiosis I. Reproduction 146, R61–R71 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J., Tang J. X., Cheng J. M., Hu B., Wang Y. Q., Aalia B., Li X. Y., Jin C., Wang X. X., Deng S. L., Zhang Y., Chen S. R., Qian W. P., Sun Q. Y., Huang X. X., Liu Y. X., Cyclin B2 can compensate for Cyclin B1 in oocyte meiosis I. J. Cell Biol. 217, 3901–3911 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daldello E. M., Luong X. G., Yang C.-R., Kuhn J., Conti M., Cyclin B2 is required for progression through meiosis in mouse oocytes. Development 146, dev172734 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones K. T., Lane S. I., Molecular causes of aneuploidy in mammalian eggs. Development 140, 3719–3730 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller M. P., Unal E., Brar G. A., Amon A., Meiosis I chromosome segregation is established through regulation of microtubule-kinetochore interactions. eLife 1, e00117 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou C., Miao Y., Cui Z., ShiYang X., Zhang Y., Xiong B., The cohesin release factor Wapl interacts with Bub3 to govern SAC activity in female meiosis I. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax3969 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y., Li S., Cui Z., Dai X., Zhang M., Miao Y., Zhou C., Ou X., Xiong B., The cohesion establishment factor Esco1 acetylates α-tubulin to ensure proper spindle assembly in oocyte meiosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 2335–2346 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y., Dai X., Zhang M., Miao Y., Zhou C., Cui Z., Xiong B., Cohesin acetyltransferase Esco2 regulates SAC and kinetochore functions via maintaining H4K16 acetylation during mouse oocyte meiosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 9388–9397 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S10