Abstract

Graduate medical training is an opportune time to improve provider delivery of STI screening. A survey of trainees found that the majority feel sexually transmitted infection screening is their job but identified barriers to successful screening. Training that intentionally address service-specific barriers will be valuable in ending the STI epidemic.

Short summary:

A survey of graduate medical trainees found that the majority feel sexually transmitted infection screening is their job but identified barriers to successfully screening their patients

Background:

Rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States and New York City (NYC) have been increasing since 2014.1,2 Untreated STIs account for substantial healthcare costs and may lead to further health complications; some, such as syphilis and gonorrhea, are a reliable marker of HIV acquisition.3–5

Currently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends routine gonorrhea and chlamydia screening for sexually active women 24 years of age or younger and older women who are at increased risk of HIV.6 The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend broader routine screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia, including in men who have sex with men, individuals on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), persons living with HIV, and young men in high prevalence clinical settings.7 STIs are frequently asymptomatic; consequentially, risk-based screening can limit the clinical and public health impact of STI screening.8,9 Additionally, patient stigma may affect STI risk factor disclosure, and provider stigma and discomfort may result in incomplete sexual history-taking, STI testing and treatment.10,11 Strategies to reverse STI trends will require expansion of routine STI testing and treatment beyond sexual health service platforms and integration into other health services.12 Integrating sexual and reproductive health (SRH) into other health services poses challenges at many health-system levels including the provider-level.10,11,13

Graduate medical education, in which resident physicians complete mentored-training, is an opportunity to improve provider delivery of STI screening and treatment as physicians establish medical practices that continue throughout their professional careers.14,15 Because residents are “durably imprinted” during this training period, incorporating STI screening and treatment into the training curriculum can support future practices like the identification, management, and prevention of STIs, their sequelae, and other co-infections like HIV.

Methods:

Design and Setting:

We conducted an online, anonymous, cross-sectional survey of residents at all stages of training within four residency programs at a single academic medical center between August 2017 and August 2018. All residents (N=298) in Internal Medicine (IM), Emergency Medicine (EM), Obstetrics and Gynecology (Ob/Gyn), and Pediatrics (Peds) were invited by chief residents, program directors, and faculty to complete the survey via email. Up to five recruitment reminders were sent and trainees received a twenty-five dollar gift card for completion.

Questionnaire:

The survey instrument was developed based on a review of the published literature and clinical experience of the investigative team. We assessed attitudes and practices around sexual health with a focus on perceived barriers to the provision of sexual health services (i.e., HIV screening, STI screening, provision of pre and post-exposure prophylaxis services and Hepatitis C virus screening (HCV)). Responses regarding HCV testing have been previously reported.16 For purposes of this study, routine STI screening was defined as “lab-based screening for patients over age 13 in the absence of symptoms,” and STIs were limited to, gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis.

Participants were first asked to use a 5-point Likert-type scale (1-strongly disagree; 5-strongly agree) to describe their attitudes towards and personal experiences with routine STI screening.

Participants were then asked to identify their top three barriers to routine STI screening based on a list of 12 barriers generated from the literature. The barriers were organized into four domains: constraints on the health delivery system and competing demands on the provider’s time (4 items); follow-up of results (3 items); the provider’s patient population (3 items); and training issues (2 items).

Data analysis:

We conducted descriptive analyses to summarize the sample; analyses were performed for the full cohort and for each individual residency program. Likert responses were treated as ordinal data, ranking the most negative response as 1 and most positive as 5. Where applicable, responses were grouped. For each barrier, we report the frequency and percentage of individuals who chose that item.

This research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Results:

Trainee characteristics:

Of the 298 eligible trainees, 142 (48%) completed the survey. Response rate did not differ by specialty, with a range of 46% (Peds) to 49% (IM). Overall, residents were more likely to be female (61%) and Caucasian (75%) and had a median age of 29 (IQR 27– 30). Most trainees self-identified as heterosexual; 10% identified as members of a sexual minority. Overall, residents reported taking an in-depth sexual history for 39% (IQR 19 −70) of patients ranging from 10% (6–30) among ED trainees to 75% (50–81) in Pediatrics.

STI screening responsibilities and implementation:

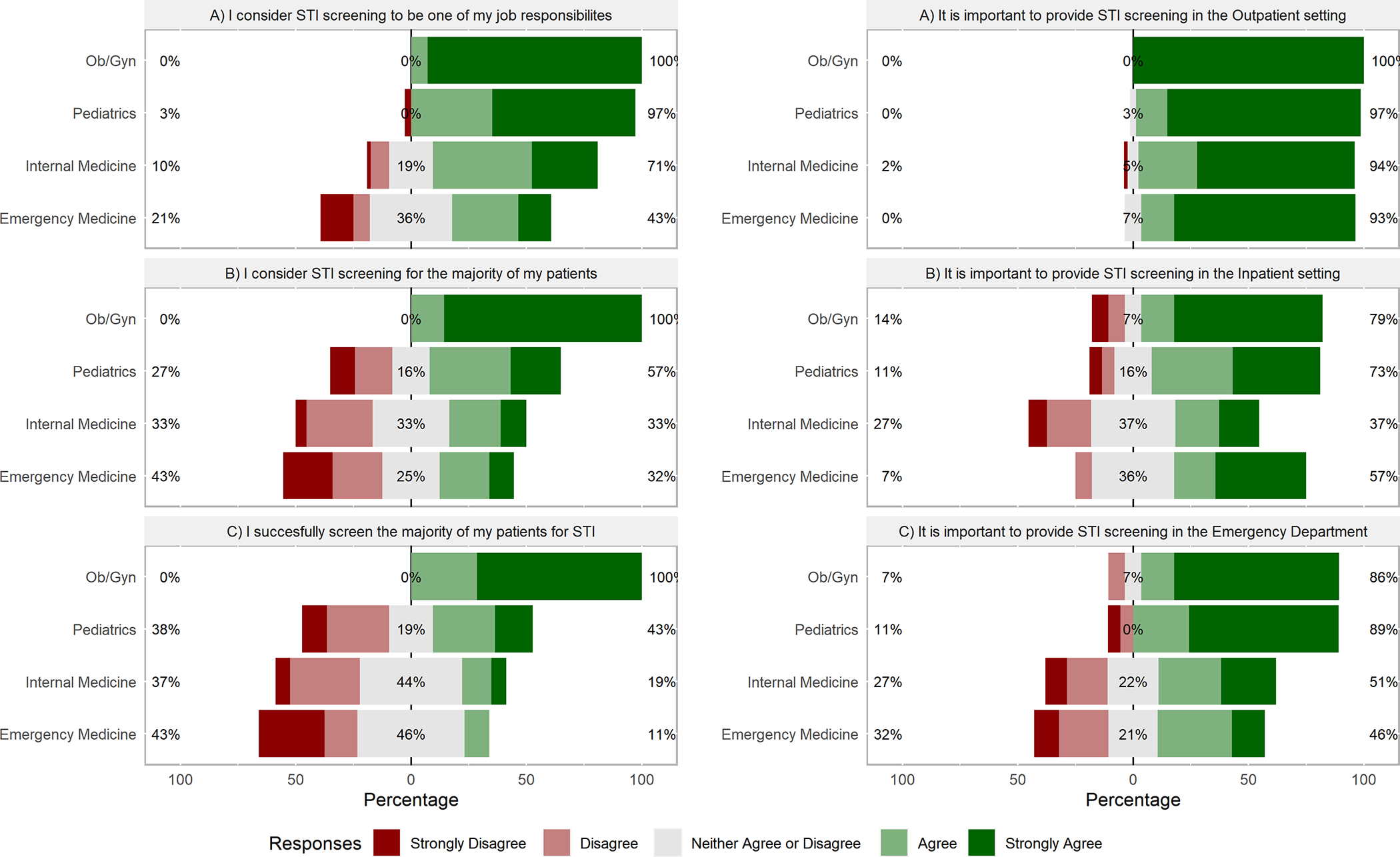

Most providers considered STI testing as one of their job responsibilities; this attitude was more common among OB/GYN and Peds trainees (100% and 97%, respectively) compared with EM trainees (43%). Most OB/GYN reported considering screening and successfully screening patients (100% and 87%), whereas fewer than half of EM trainees did (32% and 11%, respectively). (Figure 1)

Figure 1:

Attitudes and Beliefs About Sexually Transmitted Infection Screening

Attitudes towards routine STI screening by location:

Respondents universally agreed STI screening should occur in the outpatient setting. Whereas most OB/GYN and Peds trainees agreed STI screening should occur in the inpatient setting, this attitude was less common among IM and EM trainees (79%, 73%, 37%, 57% respectively). Similar patterns occurred among OB/GYN, Peds, IM, and EM trainees regarding ED screening (86%, 89%, 51%, 46%, respectively). (Figure 1)

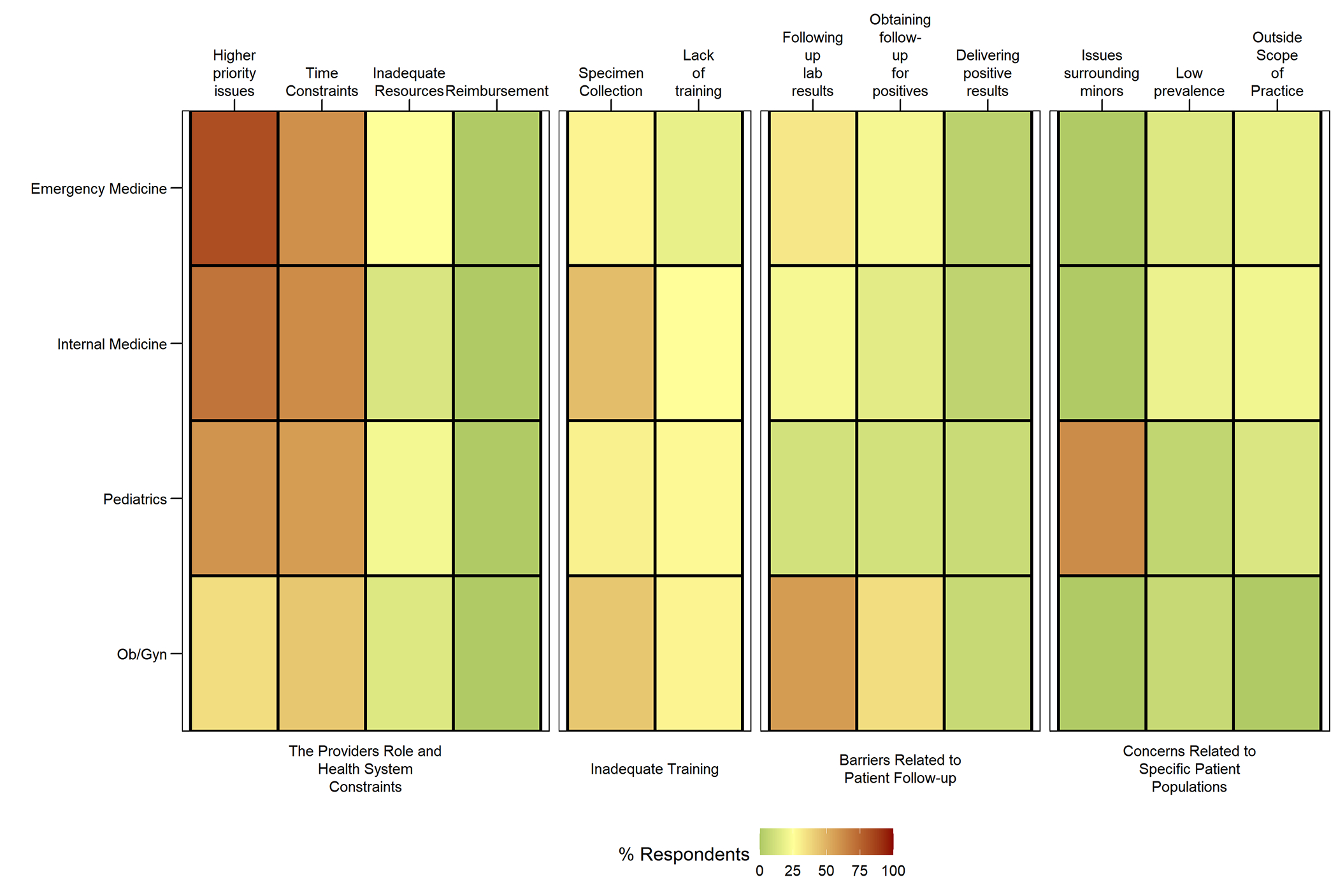

Barriers to routine STI screening:

Of the four domains examined, health systems constraints posed the greatest barrier to respondents across all training programs, followed by inadequate training. Specifically, higher priority issues and time constraints were the most frequently cited systems barriers for EM (82%, 61%), IM (70%, 62%), Peds (60%, 57%), and Ob/Gyn (36%, 43%). Finally, a lack of STI specific training and issues around specimen collection was most cited by Ob/Gyn (42%, 29%), followed by IM (46%, 25%), EM (29%, 18%), and Peds (30%, 27%). Few respondents had concerns about the patient population and ability to follow-up. However, 62% of pediatric trainees were concerned about minors’ issues. Lab result follow-up and arranging follow-up visits were most cited by Ob/Gyn (57%, 36%). Although low, 21% of IM and 18% of EM felt STI testing was outside their scope of practice; 19% of IM and 14% of EM perceived the prevalence of STIs to be low. (Figure 2)

Figure 2:

Self-Reported Barriers to Routine STI Testing Amongst Trainees

Discussion:

In this study, we found that while most residents thought that STI screening was within their scope, a much lower proportion could do so successfully, and health system barriers were considered to be the biggest hindrance. While generalizability is limited by the sample size (n=142), response rate (48%), and the fact that this is a single center study focused on medical trainees;these findings highlight opportunities for SRH / STI integration opportunities based on provider’s perception of their role and for improvements in medical education.

Sexual history taking is an important first step in STI screening and treatment. Providers who take a sexual history are more likely to provide sexual health care.17 Yet only a minority of residents in this study took a routine sexual history. More studies elucidating best-practices within medical education for population-specific sexual history taking are needed.18 Although didactic lectures are most common, data suggest that interactive workshops are a more effective learning strategy.18 Supportive supervision specific tasks like specimen collection and for trainees with special populations are another opportunity to bolster STI integration.

There is a relationship between intention to change and behavior change among medical providers.19,20 Although trainees felt screening patients for STIs was their job responsibility, they cite competing priorities and time as health-system factors that stand in the way of incorporating routine STI screening into their medical practice. While STI screening consideration and successful screening are high among OB trainees, the fall-off among all other trainees requires attention. Substantial resistance among EM and IM trainees to ED and inpatient screening highlights the need to examine integration approaches that improve efficiencies, particularly in the ED. While challenging, there are ways to address these issues.

There were also several modifiable barriers reported. Programs that allow for self-collection of samples may assist in reducing the physician burden and time commitment.21 Arranging follow-up visits overall and for those who test positive was a notable concern by providers across specialties. At our institution, a sexual health phone line is available to guide follow-up, including same-day appointments. Lack of awareness of this support service or the limited hours of the service (9 AM-5 PM) may be potential barrier that can be addressed. Additionally, many institutions have services that rapidly reach out to providers after a patient test positive for HIV; implementing similar STI services could reduce concerns over receiving a positive result.

Trainees cited managing a positive result as a barrier that can also be addressed with training and support. Attendance at STI training of 4 hours or more was shown to predict STI-specific clinical practice changes.20 Many training programs have adopted an academic half-day instead of “noon conference” to improve trainee knowledge acquisition.22 Utilizing a longer academic half-day for sexual health training may reduce this barrier. Furthermore, residency programs can have residents complete the national STD curriculum over the course of their training or partner with local CDC funded STD prevention training centers for personalized trainings.

Conclusion:

Reversing the STI epidemic will require efforts across clinical specialties. Medical education can “imprint” positive sexual health screening behaviors on providers, leading to increases in STI testing. Trainees believe sexual health screening is their job; this is a corollary of the intention to change. Good support services and training that intentionally addresses service-specific barriers will be valuable in ending the STI epidemic.

Source of Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AI150378 and L30AI133789. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None

References:

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. DOI: 10.15620/cdc.79370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New York State Department of Health Bureau of Sexual Health and Epidemiology - Sexually Transmitted Infections Surveillance Report – 2017. Available at: www.health.ny.gov/statistics/diseases/communicable/std/docs/sti_surveillance_report_2017.pdf Accessed May 1, 2019.

- 3.Peterman TA, Newman DR, Maddox L, et al. Risk for HIV following a diagnosis of syphilis, gonorrhea or chlamydia: 328,456 women in Florida, 2000–2011. Int J STD AIDS. 2015.26(2):113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, et al. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010.53(4):537–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Blank S, Schillinger JA. HIV incidence among men with and those without sexually transmitted rectal infections: estimates from matching against an HIV case registry. Clin Infect Dis. 2013.57(8):1203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Chlamydia and gonorrhea: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014December16;161(12):902–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Jun 5;64(RR-03):1–137. Erratum in: MMWR Recomm Rep 2015August28;64(33):924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durukan D, Read TRH, Bradshaw CS, et al. Pooling pharyngeal, anorectal, and urogenital samples for screening asymptomatic men who have sex with men for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol. 2020.58(5):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein PW, Martin IBK, Quinlivan EB, et al. Missed opportunities for concurrent HIV-STD testing in an academic emergency department. Public Health Rep. 2014.129 (SUPPL. 1):12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause VE. Increasing provider awareness to detect, treat, and reduce sexually transmitted infections in male service members. Available at: https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/bitstream/handle/10755/20918/Krause_DNPPaper.pdf.Accessed November 1, 2020.

- 11.Quezada-Yamamoto H, Dubois E, Mastellos N, Rawaf S. Primary care integration of sexual and reproductive health services for chlamydia testing across WHO-Europe: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019October17;9(10):e031644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palaiodimos L, Herman HS, Wood E, et al. Practices and Barriers in Sexual History Taking: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Public Adult Primary Care Clinic. J Sex Med. 2020August;17(8):1509–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Integration of Public Health and Primary Care: A Practical Look at Using Integration to Better Prevent and Treat Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Available at: https://www.astho.org/Infectious-Disease/Hepatitis-HIV-STD-TB/Sexually-Transmitted-Diseases/STD-Integration-Report.Accessed November 1, 2019.

- 14.Phillips RL Jr, Petterson SM, Bazemore AW, et al. The Effects of Training Institution Practice Costs, Quality, and Other Characteristics on Future Practice . Ann Fam Med. 2017March;15(2):140–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dine CJ, Bellini LM, Diemer G, et al. Assessing Correlations of Physicians’ Practice Intensity and Certainty During Residency Training. J Grad Med Educ. 2015December;7(4):603–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winetsky D, Zucker J, Carnevale C, et al. Attitudes, practices and perceived barriers to hepatitis C screening among medical residents at a large urban academic medical center. J Viral Hepat. 2019November;26(11):1355–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brookmeyer KA, Coor A, Kachur RE, et al. Sexual History Taking in Clinical Settings: A Narrative Review. Sex Transm Dis. 2020October21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coverdale JH, Balon R, Roberts LW. Teaching sexual history-taking: a systematic review of educational programs. Acad Med. 2011December;86(12):1590–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: A systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implementation Science. 2008December1;3(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voegeli C, Fraze J, Wendel K, et al. Predicting Clinical Practice Change: An Evaluation of Trainings on Sexually Transmitted Disease Knowledge, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Sex Transm Dis. 2021January;48(1):19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogale Y, Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, et al. Self-collection of samples as an additional approach to deliver testing services for sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2019April22;4(2):e001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha D, Faulx M, Isada C, et al. Transitioning from a noon conference to an academic half-day curriculum model: effect on medical knowledge acquisition and learning satisfaction. J Grad Med Educ. 2014March;6(1):93–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]