Abstract

Purpose:

Up to 10% of acute type A aortic dissection (TAAD) patients are deemed unfit for open surgical repair, exposing these patients to high mortality rates. In recent years, thoracic endovascular aortic repair has proven to be a promising alternative treatment modality in specific cases. This study presents a comprehensive overview of the current state of catheter-based interventions in the setting of primary TAAD.

Methods:

A literature search was conducted, using MEDLINE and PubMed databases according to PRISMA guidelines, updated until January 2020. Articles were selected if they reported on the endovascular repair of DeBakey Type I and II aortic dissections. The exclusion criteria were retrograde type A dissection, hybrid procedures, and combined outcome reporting of mixed aortic pathologies (e.g., pseudoaneurysm and intramural hematoma).

Results:

A total of 31 articles, out of which 19 were case reports and 12 case series, describing a total of 92 patients, were included. The median follow-up was 6 months for case reports and the average follow-up was 14 months for case series. Overall technical success was 95.6% and 30-day mortality of 9%. Stroke and early endoleak rates were 6% and 18%, respectively. Reintervention was required in 14 patients (15%).

Conclusion:

This review not only demonstrates that endovascular repair in the setting of isolated TAAD is feasible with acceptable outcomes at short-term follow-up, but also underlines a lack of mid-late outcomes and reporting consistency. Studies with longer follow-up and careful consideration of patient selection are required before endovascular interventions can be widely introduced.

Keywords: ascending aorta, stent graft, systematic review, thoracic endovascular aortic repair, type A dissection

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Type A aortic dissection (TAAD) is a complex and challenging disease with morbidity and surgical mortality as high as 20%.1–3 In the acute phase, patients are exposed to increased mortality risk, estimated to be 1% each hour after the onset of symptoms, and up to 95% in-hospital mortality for medically treated acute TAAD patients.2,4,5 Considering the life-threatening course of this pathology, emergent intervention is paramount. Open surgical intervention is considered to be the gold standard in contemporary treatment, with acceptable outcomes.6,7

In recent years, thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) has been established as a viable treatment modality for various descending thoracic aortic pathologies with favorable outcomes.8–10 Moreover, the use of TEVAR has gradually progressed to the aortic arch and even ascending aorta, making it one of the last frontiers of endovascular aortic therapy. When considering patients who present with an acute TAAD, approximately 10% are deemed unfit for open surgical intervention, due to high and/or prohibitive risk.2,4 Recent studies report widely varying percentages (2%–79%) of inoperable patients with anatomy amenable for catheter-based interventions.11,12 Since the first TAAD endovascular repair, performed in 2000, endovascular therapy has seen rapid technological advancements in both device design and the capabilities of imaging technology used to assess endovascular candidacy and plan intervention.13 As such, endovascular aortic repair has emerged as a feasible and potentially suitable alternative for patients who are deemed unfit to undergo surgical intervention. Endovascular repair of TAAD is an understudied field, presenting novel challenges in device and delivery system design, and the endovascular procedure itself. In recent years, various studies reported on the endovascular repair of aortic arch and ascending aortic disease.14–20 However, there are distinct differences in anatomy and complexity of disease when dealing with a dissected aorta. Compared to conditions such as aneurysms, intramural hematoma (IMH), or penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer (PAU), dissection is characterized by loss of structural wall integrity through delamination and complicates the identification of stable landing zones.20 Therefore, we aim to present a comprehensive literature overview of contemporary results of TEVAR, exclusively in the setting of TAAD with an entry tear in the ascending aorta.

2 |. METHODS

A thorough search of the MEDLINE and PubMed database was conducted, updated until January 2020. The used search terms were “Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair,” “Type A Dissection,” and “Ascending Aorta,” including all variations of these terms. Relevant articles retrieved from the reference lists were subsequently added. The search was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.21 Two authors (Yunus Ahmed and Ignas B. Houben) independently extracted and assessed all data for eligibility and reached the consensus on the final selection. Articles were included if they reported on the endovascular intervention of TAAD, with the entry tear located in the ascending aorta (i.e., DeBakey Classification I and II). The exclusion criteria were retrograde TAAD and hybrid procedures. Supra-aortic arch revascularization and debranching procedures before endovascular repair of TAAD were not excluded. Furthermore, articles reporting on combined aortic pathology in the ascending aorta (e.g., thoracic aortic aneurysm [TAA]/pseudoaneurysm, IMH, or PAU) that did not explicitly report on TAAD outcomes were excluded.

3 |. RESULTS

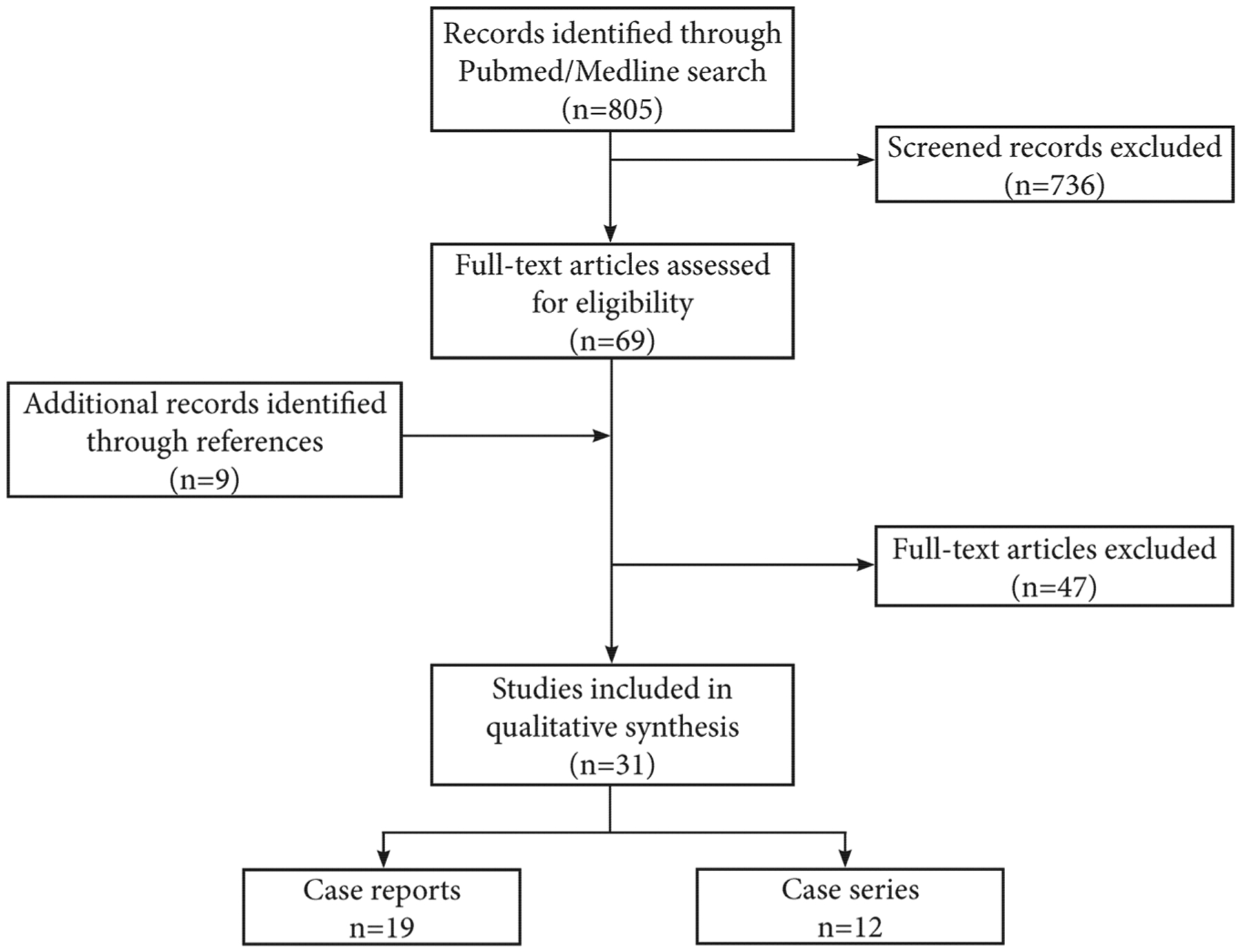

The initial search yielded a total of 805 articles, out of which 736 were excluded based on title and/or abstract. The remaining 69 articles were thoroughly reviewed for eligibility, in addition to 9 articles that were extracted from selected articles reference lists. An additional 47 articles were excluded owing to the description of pathology other than ascending aortic dissection, intervention other than endovascular ascending aortic repair with stent graft or inadequate or duplicate reporting of outcomes. At the completion of the review, 31 studies were included (19 case reports and 12 case series), describing a total of 92 patients who underwent ascending aortic endovascular repair for TAAD (Figure 1).13,22–51 The selected studies were published between 2000 and 2019.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study selection process for eligible studies

Patients presented with acute (n = 55), subacute (n = 10), or chronic TAAD (n = 27), defined as 0–14 days, 15–90 days, and >90 days after the onset of symptoms, respectively. Fourteen studies reported on the timing of intervention for patients presenting with acute TAAD. Only four of these studies, describing a total of eight patients, reported patients who were treated within 24 h after the onset of symptoms.32,33,39,39,51 Indications for endovascular repair were high and/or prohibitive in all but two cases; these patients refused high-risk open surgery or preferred endoluminal stent graft placement.22,28 Preoperative demographics are reported in Tables 1 and 2 for the case reports and case series, respectively. Heterogeneity in reported literature precluded any meta-analysis of the data.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and comorbidities of selected case reports

| Author | Year | Indication | Mean age | Gender | Comorbidities | Relevant surgical history | Significant aortic insufficiency | Hospital stay (days) | Average follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorros13 | 2000 | Chronic TAAD | 56 | Female | CAD | CABG, open TAAD repair | N/S | N/S | 0.75 |

| Zhang22 | 2004 | Subacute TAAD | 46 | Female | CAD | None | N/S | N/S | 12 |

| Ihnken33 | 2004 | Acute TAAD | 89 | Female | None | None | N/S | 12 | N/S |

| Zimpfer44 | 2006 | Acute TAAD | 84 | Male | DM, CVA, and RF | None | N/S | 7 | 1 |

| Senay46 | 2007 | Acute TAAD | 66 | Male | Lung cancer | Open lobectomy | N/S | 5 | N/S |

| Palma47 | 2008 | Chronic TAAD | 63 | Male | COPD, RF, HTN, DM, and CVA | None | No | N/S | N/S |

| Metcalfe48 | 2012 | Acute TAAD | 68 | Female | HTN and RF | None | N/S | N/S | N/S |

| Shabaneh49 | 2013 | Acute TAAD | 70 | Male | AEF, CAD, COPD, and RF | AAA repair, EVAR, esophagectomy, and CABG | No | 4 | 1 |

| Pontes50 | 2013 | Acute TAAD | 84 | Female | COPD, DM, CHF, and RF | None | N/S | N/S | N/S |

| McCallum51 | 2013 | Ruptured chronic TAAD | 77 | Male | CAD | Post heart transplant, sternotomy x4 | N/S | N/S | 25 |

| Kölbel23 | 2013 | Acute TAAD | 67 | Male | COPD, CHF, and RF | None | No | 10 | 5 |

| Luo24 | 2014 | Acute TAAD | 56 | Female | CAD and RF | Heart-transplant | No | N/S | 6 |

| Atianzar25 | 2014 | Acute TAAD | 79 | Male | N/S | None | No | 1.5 | N/S |

| Wilbring26 | 2015 | Acute TAAD | 82 | Male | AoS, RF, COPD, DM, and CVA | None | No | N/S | 6 |

| Berfield27 | 2015 | Acute TAAD | 95 | Female | CHF and AoS | TAVR | Yes | 7 | 2 |

| Rohlffs28 | 2016 | Chronic TAAD | 72 | Male | CAD and COPD | fEVAR for TAAA | N/S | 4 | N/S |

| Muetterties29 | 2017 | Acute TAAD | 48 | Female | HTN and RF | None | No | 4 | 24 |

| Kong30 | 2019 | Chronic TAAD | 65 | Male | N/S | Mitral valve repair and aortic valve repair | No | 5 | N/S |

| Wamala31 | 2019 | Acute TAAD | 91 | Male | CAD, DM, RF, COPD, and HTN | EVAR | N/S | 7 | 12 |

Abbreviations: AEF, aorto-esophageal fistula; AoS, aortic stenosis; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DM, diabetes mellitus; fEVAR, fenestrated endovascular aortic repair; HTN, hypertension; N/S, not specified; RF, renal failure; TAAA, thoraco-abdominal aneurysm; TAAD, type A aortic dissection; TBAD, Type B aortic dissection.

TABLE 2.

Demographics and comorbidities of selected case series

| Author | Year | N (TAAD) | Indication | Mean age | Male, n (%) | Comorbidities | Relevant surgical history | Significant aortic insufficiency, n (%) | Hospital stay (days) | Average follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ye32 | 2011 | 10 | 6 acute TAAD, 4 chronic TAAD | 51 | 9 (90) | HTN | None | N/S | N/S | N/S |

| Ronchey34 | 2013 | 4 | 4 acute TAAD | 70 | 2 (50) | HTN, DM, and COPD | AVR, open TAAD repair | N/S | N/S | 15 |

| Bernardes35 | 2014 | 3 | 2 acute TAAD, 1 chronic TAAD | 54 | 0 | HTN and CAD | Open TAAD repair | N/S | N/S | 2.5 |

| Roselli36 | 2015 | 11 | 11 acute TAAD, 2 chronic TAAD | 74 | 6 (55) | HTN, CAD, DM, COPD, RF, CVA, and CHF | Cardiovascular Surgery | N/S | N/S | N/S |

| Vallabhajosyula37 | 2015 | 2 | 2 acute TAAD | 84 | 0 | HTN, CAD, CVA, and HCC | None | N/S | N/S | 9 |

| Khoynezad38 | 2016 | 2 | 1 acute TAAD, 1 chronic TAAD | 86 | 1 (50) | HTN and deep vein thrombosis | Cardiovascular Surgery | N/S | N/S | 8 |

| Li39 | 2016 | 15 | 1 acute TAAD, 7 subacute TAAD, 7 chronic TAAD | 65 | 12 (80) | COPD and RF | Sternotomy | 2 (13%) | 9.4 | N/S |

| Nienaber40 | 2016 | 12 | 6 acute TAAD, 6 chronic TAAD | 81 | 9 (75) | CAD, COPD, and RF | None | None | N/S | 19 |

| Murakami41 | 2017 | 1 | 1 subacute TAAD | 66 | 0 | HTN, CAD, RF, and CVA | None | 1 (100%) | N/S | N/S |

| Grieshaber42 | 2018 | 4 | 3 acute TAAD, 1 subacute TAAD | 63 | 3 (75) | CAD, COPD, RF, and CVA | Open TAAD repair | None | N/S | N/S |

| Hsieh43 | 2019 | 1 | Acute TAAD | 79 | 0 | CVA | None | N/S | 1 | 10 |

| Ghoreishi45 | 2019 | 8 | 7 acute TAAD, 1 chronic TAAD | 69 | N/S | CAD, COPD, and RF | CABG | 2 (25%) | 7.5 | 12 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DM, diabetes mellitus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HTN, hypertension; N/S, not specified; RF, renal failure; TAAD, type A aortic dissection.

3.1 |. Operative management and technique

The use of anesthesia was described in 23 studies, with 98% of cases performed under general anesthesia. Two main methods of blood pressure management to assure accurate stent graft deployment were used; rapid ventricular pacing (reduction of cardiac output by pacing the right ventricle at 180–220 beats per minute) in 77% of patients and medicine induced hypotension or cardiac arrest (use of sodium nitroprusside and adenosine to achieve controlled hypotension or intermittent cardiac arrest, respectively) in 22%.52 Alternatively, one patient received venous inflow occlusion and in one patient a TandemHeart (CardiacAssist, Inc.) was applied in addition to rapid ventricular pacing (Tables 3 and 4). Moreover, in 75% of cases, the procedure was performed under transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) guidance. The endografts used in each study are reported in Tables 3 and 4. Out of all 31 studies, transfemoral access as a device delivery route was reported in 72 patients (78%; Tables 3 and 4). Other types of vascular access were transapical (n = 14, 15%), transcarotid (n = 2, 2%), or transaxillary (n = 4, 4%). Insufficient additional specifics were reported regarding the mode of access (i.e., cut-down or percutaneous). Overall technical success was 95.6%.

TABLE 3.

Operative details of selected case reports

| Author | Endograft specification | Device delivery | Anesthesia | Device deployment approach | TEE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorros13 | OSD, Lacteba | Transfemoral | General | Adenosine induced cardiac arrest | No |

| Zhang22 | Gianturco Z, Cook Medical | Transfemoral | Epidural | N/S | No |

| Ihnken33 | Excluder Endoprosthesis, W.L. Gore | Transfemoral | General | N/S | Yes |

| Zimpfer44 | CMD, Jotec | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Senay46 | Valiant, Medtronic | Transfemoral | General | N/S | No |

| Palma47 | CMD, Braile Biomedical | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing | No |

| Metcalfe48 | Zenith Ascend Dissection, Cook Medical | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing | No |

| Shabaneh49 | Zenith TX2, Cook Medical | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing + tandem heart | Yes |

| Pontes50 | N/S | Transfemoral | General | Induced hypotension | No |

| McCallum51 | Talent, Medtronic | Transfemoral | N/S | Adenosine induced cardiac arrest | No |

| Kölbel23 | Zenith TX2, Cook Medical | Transapical | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Luo24 | Valiant, Medtronic | Transapical | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Atianzar25 | Valiant, Medtronic | Transfemoral | Spinal | Induced hypotension | No |

| Wilbring26 | Relay NBS, Bolton Medical | Transfemoral | N/S | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Berfield27 | Modified Zenith TX2, Cook Medical | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Rohlffs28 | Scalloped Zenith Ascend TAA, Cook Medical | Transfemoral | N/S | Venous inflow occlusion | Yes |

| Muetterties29 | Excluder Endoprosthesis, W.L. Gore | Transaxillary | General | Adenosine induced cardiac arrest | Yes |

| Kong30 | W.L. GORE | Transfemoral | N/S | Induced hypotension | No |

| Wamala31 | Jotec Evita | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

Abbreviations: CMD, custom made device; N/S, not specified; OSD, off the shelf device; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram.

TABLE 4.

Operative details of selected case series

| Author | Endograft specification | Device delivery | Anesthesia | Device deployment approach | TEE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ye32 | Talent, Medtronic; Zenith, Cook Medical; Ancure II, XianJuan; Aegis, Microport | Transfemoral Transcarotid |

General | Induced hypotension | No |

| Ronchey34 | Zenith TX2 TAA, OSD, Cook Medical | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Bernardes35 | Zenith, Cook Medical; TAG, W.L. Gore; Valiant, Medtronic | Transfemoral | General | Induced hypotension | No |

| Roselli36 | W.L. Gore; Medtronic; Cook Medical | Transfemoral Transapical Transaxillary |

General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Vallabhajosyula37 | Zenith TX2 TAA, Cook Medical | Transapical | N/S | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Khoynezad38 | Valiant PS-IDE, Medtronic | Transfemoral | N/S | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Li39 | Zenith TX2 TAA, Cook Medical | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Nienaber40 | Zenith TX2 TAA, Cook Medical; Relay NBS, Bolton; C-TAG, W.L. Gore; Nitinol Stent, Optimed | Transfemoral | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Murakami41 | Zenith TX2 TAA, Cook Medical | Transapical | General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Grieshaber42 | CMD, Bolton Medical | Transfemoral Transapical |

General | Rapid pacing | Yes |

| Hsieh43 | Medtronic | Transfemoral | General | N/S | No |

| Ghoreishi45 | W.L. Gore TAG or Excluder | Transfemoral Transaxillary |

General | Raped pacing | Yes |

Abbreviations: CMD, custom made device; N/S, not specified; OSD, off the shelf device; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram.

3.2 |. Hospital stay and follow-up

The hospital stay was described in 11 case reports with a median of 5 days (range: 1.5–12 months). In only two out of 12 case series, hospital stay was described, averaging 8.7 days over a total of 23 patients. Follow-up was described in 10 case reports with a median of 6 months (range: 1–25 months). In the case series, follow-up was described in 7 studies (32 patients), averaging 14 months (range: 18–39 months).

3.3 |. Complications

Early endoleak, within 30 days, occurred in 17 out of 92 patients (18%), and 4 patients required additional management using stent graft extensions.35,37,51 One patient received an Amplatzer plug to treat type 1 A endoleak.49 This was achieved through transapical access, after which the plug was used to eliminate residual flow across the entry tear at the proximal aspect of the stent graft. Late endoleak occurred in nine patients (10%). Most patients with endoleak developed no major complications, other than additional endovascular procedures. Subdividing the occurrence of endoleaks into proximal and distal leaks was impossible, as the location was not explicitly reported in all studies. However, most of the bird-beak signs (i.e., the wedge-shaped gap between endograft and aortic wall due to incomplete apposition of the proximal portion of the endograft) were seen in the distal landing zone, as can be expected from its curved geometry.53

Rare complications included stent graft induced new entry-tears (SINE; n = 2), accidental covering of branch vessels (n = 1), iatrogenic dissection (n = 1), and retained delivery systems (n = 1), all of which required open surgical repair.35,36,45

Overall, 30-day mortality was 9% (Table 5), with breakdowns of 11%, 0%, and 4% for acute, subacute, and chronic type A dissection, respectively. The 30-day event-free survival (i.e., freedom from death, reintervention, or major complication) was 71%. Short-term mortality was 16%. Short-term event-free survival at a 2-year follow-up could not be reported. The stroke rate was 6% (6 out of 92).

TABLE 5.

In-hospital and short-term outcomes of selected case reports and case series

| Case reports No. of patients (%) | Case series No. of patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Early outcomes | Total n = 19 | Total n = 73 |

| Technical success | 19 (100) | 69 (95) |

| Endoleak | 4 (21) | 13 (18) |

| Stroke | 1 (5) | 5 (7) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (5) | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory failure requiring prolonged ventilation or intubation | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Aortic insufficiency | 1 (5) | 1 (1) |

| 30-day mortality | 2 (11) | 6 (8) |

| 30-day event-free survival | 9 (75)a | 51 (71)b |

| Short-term outcomes | Total n = 17 | Total n = 67 |

| Endoleak | 1 (6) | 5 (7) |

| Short-term mortality | 0 | 11 (16) |

| Stent graft-induced new-entry tears | 0 | 3 (4) |

Seven patients were excluded due to a follow-up of less than 30 days.

One patient was excluded due to a follow-up of less than 30 days.

3.4 |. Additional procedures

With the exception of one study describing concomitant PCI in the setting of coronary artery disease (CAD), no studies reported on the treatment of CAD.46 Eight patients (9%) required arch vessel debranching before TEVAR, while intraoperative aortic arch branching procedures were performed in six cases (7%; Table 6), using a chimney, fenestration, or branched stent graft. Additional stenting or ballooning for endoleak or aortic valve entrapment was performed in six cases (7%). Two patients (2%) required direct open conversion.

TABLE 6.

Additional procedures and reinterventions

| Case reports (n = 19) n (%) | Case series (n = 73) n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative procedures | Arch vessel debranching | 0 (0) | 8 (11) |

| Branching procedures | 2 (11) | 4 (5) | |

| Additional stenting | 1 (5) | 3 (4) | |

| Additional ballooning | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | |

| Open conversion | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| Coronary stenting | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | |

| Reinterventions | Open | 1 (5) | 9 (12)a |

| Endovascular | 0 (0) | 4 (5) |

Three out of nine reinterventions were related to vascular access complications.

3.5 |. Reinterventions

Ten patients (11%) underwent open reintervention, whereas four patients (4%) underwent endovascular reintervention (Table 6). Open reinterventions were performed SINE (n = 3),35,39 Type I endoleak (n = 1),36 severe AI (n = 1),22 PAU (n = 1),38 iatrogenic femoral artery dissection (n = 1),45 pseudoaneurysm (n = 2),32,36 and pericardial effusion (n = 1).45 Endovascular reinterventions were performed for Type I endoleak (n = 3)35,36 and severe AI (n = 1).45

4 |. DISCUSSION

Over recent years, endovascular interventions to treat TAAD have proven to be a feasible treatment modality. We report a 30-day mortality of 9% and a short-term mortality of 16%. When compared to literature data on in-hospital mortality for open surgical repair of TAAD, ranging between 16% and 20%, these results suggest that endovascular repair is an acceptable alternative for patients who are deemed unfit to undergo open surgical repair for type A dissection.2,54 It is important to note that, similar to type B aortic dissection, acuity of disease in TAAD impacts both patient presentation and outcome.55 Patients presenting with subacute/chronic TAAD have better short- and long-term survival rates when compared to acute TAAD patients.3 Stroke incidence with endovascular treatment of TAAD of 6% was no higher than previous reports from arch TEVAR56–58 and open TAAD repair.4,54,59

Given the novelty of this procedure and the lack of long-term outcomes, there remain several topics of concern that must be adequately considered: patient selection, vascular access, stent graft design, and aortic valve involvement. These topics will be addressed below.

4.1 |. Patient selection

When considering endovascular repair in TAAD, rigorous patient selection is of paramount importance, based on both clinical and radiological characteristics. As of current, only patients who are considered too frail to undergo open surgical repair are considered for TEVAR. Patients with prohibitive fragility warrant a minimally invasive approach and require careful planning. TAAD patients presenting with visceral malperfusion syndrome represent just such a population, with increased in-hospital mortality (71%) compared to medically treated patients (57%).2,60–62 Sustained positive outcomes using a treatment approach of initial endovascular malperfusion management (i.e., fenestration of the intimal flap and/or true lumen stenting), followed by delayed open repair have been demostrated.63,64 A recent publication by Omura et al.65 demonstrates the feasibility of TEVAR and concomitant true lumen stenting in acute retrograde type A dissection with renal malperfusion. However, no cases of endovascular TAAD repair with concomitant endovascular visceral malperfusion treatment have been reported yet.

ECG-gated computed tomography (CT) scan technique is highly recommended given the requirement for motion-artifact free images for accurate measurements. Retrospective ECG-gating technique is optimal for quantification of morphometric changes of the aorta over the cardiac cycle, and for dynamic evaluation of the entry tear anatomy, particularly in acute/subacute TAAD given higher degrees of intimal flap motion.66 As of recent, various studies have explored imaging characteristics in type A dissection patients to assess feasibility of endovascular aortic repair.11,12 Ideally, 2 cm of non-dilated and nondissected aorta can be identified at both proximal and distal landing zones. Complex hemodynamics encountered in the thoraco-abdominal aorta leads to increased displacement forces on the stent graft and accentuate the need for a robust seal.67,68

4.2 |. Vascular access

When treating most proximal aortic disease, transfemoral delivery may be more limited as a result of inadequate delivery system length and higher degrees of aortic arch angulation. The iliofemoral arteries require a caliber of at least 6.5–7 mm, as most conformable thoracic endografts have a minimal profile of 20 French.69–72 Retrograde delivery routes carry an increased risk if true lumen access is not obtained at both landing zones. Wire location in the true lumen can be confirmed by IVUS examination before delivery of the endograft. Furthermore, accurate deployment may be complicated by increased spring-back forces or decreased conformability (i.e., increased rigidity) of the delivery device.73,74

Alternatively, a transapical, transcarotid, or transaxillary approach offer deployment strategies closer to the ascending aorta when compared to the transfemoral approach. Nonetheless, each of these approaches carry distinct risks. Transapical delivery is incompatible with previous implanted prosthetic mechanical valves and may potentially induce long-term complications, such as formation of left ventricular pseudoaneurysm, as reflected in this review.36,39 This approach, however, offers the unique advantage of antegrade deployment, ensuring true lumen access. Furthermore, the more in-line approach and shorter distance to the sinotubular junction (STJ) provides a lower dependence on delivery device conformability.12 Transcarotid and transaxillary access have been rarely described for proximal aortic TEVAR. In the two patients where transcarotid delivery was performed, stroke occurred within 3 weeks and 1 years postoperatively.32

4.3 |. Stent graft design

Most cases reports describe stent grafts that were originally designed for the descending thoracoabdominal aorta. Consequently, these devices are often too long for use in the ascending aorta, frequently measuring over 10 cm in length, whereas the normal length of the ascending aorta is 8–10 cm.75 Potential solutions include customizing existing descending stent grafts or using commercially approved shorter segment devices. The first option comes with significant shortcomings, as the newly exposed cut-end of the endograft may cause damage to the adjacent aortic tissue and increase risk of SINE. Furthermore, unloading and reloading the device may lead to failure during deployment. The latter option has the advantage of accounting for the higher angulation through modular grafting and the preloaded market-approved devices. However, when using shorter segment stent grafts, there is often need to deploy multiple overlapping stents to ensure coverage of the ascending aorta, with a corresponding increased risk of type IIIa endoleak (i.e., leak between endograft components) or migration. Metcalfe et al.48 were the first to describe the use of a stent graft specifically designed for the ascending aorta, with excellent results.

Stent graft design and deployment techniques need to account for the hemodynamic forces present in the ascending aorta, by ensuring adequate landing zone length and seal to withstand the displacement forces and ultimately prevent stent migration.76–78 A computational fluid dynamics study by Figueroa et al.79 evaluated net thoracic aortic stent graft displacement, demonstrating that the more proximal the endograft is implanted, the greater the cranial component of displacement.

In conventional endovascular aneurysm repair outer-to-outer-wall diameter is used for stent graft sizing and 10%–20% oversizing is generally accepted.80 However, in dissection and IMH the size of the true lumen relative to the outer-wall diameter may be discrepant, difficult to measure and variable over time. Additionally, the tissue strength of the dissected segment may be unable to bear the radial force imposed by the oversized endograft. To this extent, tissue fragility in the dissected ascending aorta must be taken into account, and stent graft oversizing of 10%–20% may be excessive, potentially causing further wall injury or rupture. Predominantly in acute dissections, oversizing of 5%–10% is advocated, whereas the amount of oversizing in chronic dissections may be higher.81–83 These oversizing rates have been based on TEVAR for descending thoracic aortic pathology, as limited ascending endovascular repair has not yet been described.

4.4 |. Aortic valve involvement

A major limitation of endovascular approach of type A repair is the limited ability to address aortic valve insufficiency (AI), either secondary to STJ malalignment or valve injury due to a proximal entry tear. In open repair for TAAD, AI can be treated using a valve resuspension technique or complete aortic valve replacement. As suggested previously by Kreibich et al.84 and more recently demonstrated by Gaia et al.,85 an “endo-Bentall” approach might allow for treatment of AI in the setting of TAAD. The authors describe a transapical approach, in which a TAVR valve is deployed simultaneously with an ascending aortic stent graft, successfully extending the proximal landing zone of the stent graft to the aortic annulus. The valve is connected to an uncovered portion of the stent graft, to allow for free diastolic coronary blood flow. In the case of an entry tear at the level of the sinus of Valsalva or lower; however, this approach may not fully exclude the entry tear, the primary goal of any TAAD repair technique. Currently, a proven endovascular solution to address significant AI is not available.

4.5 |. Limitations

This systematic review is limited by the quality of the existing literature, characterized by an overall lack of large cohort studies and prospective trials. Given the estimated incidence of acute type A dissection of 3–5 per 100,000 patients and the observation that approximately 9%–14% of patients are deemed inoperable, one would expect a broad application of novel endovascular techniques. However, in the past two decades, we have identified a total of only 92 type A dissection patients managed with TEVAR. It is therefore important to recognize the potential for publication bias in the studies reviewed in this paper, warranting caution in interpreting these early results. Further, we recognize the distinct differences in outcomes between patients presenting with acute and chronic TAAD, and the lack of a sub analysis for these cohorts is dissatisfying. Therefore, current results may not be fully generalizable to the entire TAAD population. Open repair for TAAD is still recognized as the gold standard and endovascular repair as a treatment modality still under development. Patients undergoing endovascular aortic repair represent a small subpopulation of all type A dissection patients, and thus most conclusions drawn from the current reports of endovascular TAAD repair are likely premature. To fully ascertain the role of TEVAR in the treatment of TAAD, larger studies with long-term follow-up are clearly needed. Given the heterogeneity and the small sample size of all reports, we were unable to apply more advanced statistical techniques (e.g., random-effects meta-analysis model), and are thus limited to descriptive and pooled analyses.

5 |. CONCLUSION

This systematic analysis presents a comprehensive review of isolated TEVAR management of type A dissection. Our review confirms that TEVAR is a feasible treatment option for high-risk TAAD patients and current reported mortality rates are favorable over medical treatment. However, this review also highlights the urgent need for technical advances in disease-specific device design, delivery methods, and hybrid endovascular techniques to address the need for concomitant valve replacement and/or arch endografting. Most importantly, our analysis emphasizes the significant need for larger studies with long-term results and more complete reporting of negative results before the endovascular intervention may widely proposed as an alternative to the gold standard open repair.

APPENDIX

Medline search

(Endovascular OR Transluminal OR “endovascular procedures”[MeSH Terms] OR endovascular repair OR Endovascular treatment OR Endovascular approach OR endovascular stent graft OR Trans-luminal stent graft OR TEVAR OR Thoracic endovascular aortic repair OR thoracic endovascular repair) AND (“type A dissection” OR “acute type A dissection” OR “type A aortic dissection” OR “acute type A aortic dissection” OR ascending aortic dissection) AND (“ascending aorta” OR “ascending” OR “aorta”[MeSH Terms] OR “zone 0”).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

David M. Williams: Medical advisory board for Boston Scientific; Himanshu J. Patel: Consultancy activities for W.L. Gore, Medtronic Inc., and Terumo Inc.; Joost A. van Herwaarden: Consultancy activities for Cook Medical, W.L. Gore, Medtronic Inc., and Terumo Inc; Other authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Conzelmann LO, Weigang E, Mehlhorn U, et al. Mortality in patients with acute aortic dissection type A: analysis of pre- and intraoperative risk factors from the German Registry for Acute Aortic Dissection Type A (GERAADA). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49(2): e44–e52. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pape LA, Awais M, Woznicki EM, et al. Presentation, diagnosis, and outcomes of acute aortic dissection: 17-year trends from the international registry of acute aortic dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(4):350–358. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J, Xie E, Qiu J, et al. Subacute/chronic type A aortic dissection: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;57(2): 388–396. 10.1093/ejcts/ezz209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berretta P, Patel HJ, Gleason TG, et al. IRAD experience on surgical type A acute dissection patients: results and predictors of mortality. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;5(4):346–351. 10.21037/acs.2016.05.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wee I, Varughese RS, Syn N, Choong AMTL. Non-operative management of type A acute aortic syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019;58(1):41–51. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(2):279–315. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases. Russ J Cardiol. 2015; 123(7):7–72. 10.15829/1560-4071-2015-07-7-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraha I, Romagnoli C, Montedori A, Cirocchi R. Thoracic stent graft versus surgery for thoracic aneurysm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(6):CD006796. 10.1002/14651858.CD006796.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coady MA, Ikonomidis JS, Cheung AT, et al. Surgical management of descending thoracic aortic disease: open and endovascular approaches: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(25):2780–2804. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e4d033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng D, Martin J, Shennib H, et al. Endovascular aortic repair versus open surgical repair for descending thoracic aortic disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(10):986–1001. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nissen AP, Ocasio L, Tjaden BL, et al. VESS28. Imaging characteristics of acute type A aortic dissection and candidacy for repair with ascending aortic endografts. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(6):e72–e73. 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.04.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roselli EE, Hasan SM, Idrees JJ, et al. Inoperable patients with acute type A dissection: are they candidates for endovascular repair? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;25(4):582–588. 10.1093/icvts/ivx193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorros G, Dorros AM, Planton S, Hair DO, Zayed M. Transseptal guidewire stabilization facilitates stent-graft deployment for persistent proximal ascending aortic dissection. J Endovasc Ther. 2000; 7:506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Böckler D, Brunkwall J, Taylor PR, et al. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair of aortic arch pathologies with the conformable thoracic aortic graft: early and 2 year results from a european multi-centre registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;51(6):791–800. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shijo T, Kuratani T, Torikai K, et al. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair for degenerative distal arch aneurysm can be used as a standard procedure in high-risk patients. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 2016;50(2):257–263. 10.1093/ejcts/ezw020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang T, Shu C, Li M, et al. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair with single/double chimney technique for aortic arch pathologies. J Endovasc Ther. 2017;24(3):383–393. 10.1177/1526602817698702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baikoussis NG, Antonopoulos CN, Papakonstantinou NA, Argiriou M, Geroulakos G. Endovascular stent grafting for ascending aorta diseases. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66(5):1587–1601. 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.07.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muetterties CE, Menon R, Wheatley GH. A systematic review of primary endovascular repair of the ascending aorta. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67(1):332–342. 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.06.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piffaretti G, Grassi V, Lomazzi C, et al. Thoracic endovascular stent graft repair for ascending aortic diseases. J Vasc Surg. 2019;70(5): 1384–1389. 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.01.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kratimenos T, Baikoussis NG, Tomais D, Argiriou M. Ascending aorta endovascular repair of a symptomatic penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer with a custom-made endograft. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018; 47:280.e1–280.e4. 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Li M, Jin W, Wang Z. Endoluminal and surgical treatment for the management of Stanford Type A aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26(4):857–859. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kölbel T, Reiter B, Schirmer J, et al. Customized transapical thoracic endovascular repair for acute type A dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(2):694–696. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo CM, Wang SS, Chi NH, Wu IH. Transapical endovascular repair with a table-tailored endograft to treat ascending aortic dissection. J Card Surg. 2014;29(6):824–826. 10.1111/jocs.12449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atianzar K, Mohamad A, Galazka P, Keller VA, Delafontaine P, Sam AD. Endovascular stent-graft repair of ascending aortic dissection with a commercially available thoracic endograft. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(2):715–717. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.09.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilbring M, Ghazy T, Matschke K, Kappert U. Complete endovascular treatment of acute proximal ascending aortic dissection and combined aortic valve pathology. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015; 149(4):e59–e60. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berfield KKS, Sweet MP, McCabe JM, et al. Endovascular repair for type A aortic dissection after transcatheter aortic valve replacement with a medtronic corevalve. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(4): 1444–1446. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.11.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohlffs F, Tsilimparis N, Detter C, Von Kodolitsch Y, Debus S, Kölbel T. New advances in endovascular therapy: endovascular repair of a chronic DeBakey type II aortic dissection with a scalloped stent-graft designed for the ascending aorta. J Endovasc Ther. 2016; 23(1):182–185. 10.1177/1526602815621063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muetterties CE, Conklin JH, Moser GW, Wheatley GH. Right axillary artery cannulation for endovascular repair of an acute type A aortic dissection. Innov Technol Tech Cardiothorac Vasc Surg. 2017;12(2): 140–143. 10.1097/IMI.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong M, Qian J, Duan Q, Li X, Dong A. In situ laser fenestration for revascularization of aortic arch during treatment for iatrogenic type A aortic dissection. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14(1):87. 10.1186/s13019-019-0877-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wamala I, Heck R, Falk V, Buz S. Endovascular treatment of acute type A aortic dissection in a nonagenarian: stabilization of a short covered stent using a bare-metal stent. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019;29(6):978–980. 10.1093/icvts/ivz206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye C, Chang G, Li S, et al. Endovascular stent-graft treatment for Stanford type A aortic dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011; 42(6):787–794. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ihnken K, Sze D, Dake MD, Fleischmann D, Van Der Starre P, Robbins R. Successful treatment of a Stanford type A dissection by percutaneous placement of a covered stent graft in the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127(6):1808–1810. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronchey S, Serrao E, Alberti V, et al. Endovascular stenting of the ascending aorta for type A aortic dissections in patients at high risk for open surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;45(5):475–480. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernardes RC, Navarro TP, Reis FR, et al. Early experience with off-the-shelf endografts using a zone 0 proximal landing site to treat the ascending aorta and arch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148(1): 105–112. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.07.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roselli EE, Idrees J, Greenberg RK, Johnston DR, Lytle BW. Endovascular stent grafting for ascending aorta repair in high-risk patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(1):144–154. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vallabhajosyula P, Gottret JP, Bavaria JE, Desai ND, Szeto WY. Endovascular repair of the ascending aorta in patients at high risk for open repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(2):S144–S150. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khoynezhad A, Donayre CE, Walot I, Koopmann MC, Kopchok GE, White RA. Feasibility of endovascular repair of ascending aortic pathologies as part of an FDA-approved physician-sponsored investigational device exemption. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(6):1483–1495. 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, Lu Q, Feng R, et al. Outcomes of endovascular repair of ascending aortic dissection in patients unsuitable for direct surgical repair. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(18):1944–1954. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nienaber CA, Sakalihasan N, Clough RE, et al. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) in proximal (type A) aortic dissection: ready for a broader application? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(2): S3–S11. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.07.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murakami T, Nishimura S, Hosono M, et al. Transapical endovascular repair of thoracic aortic pathology. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;43:56–64. 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grieshaber P, Nink N, Roth P, Elzien M, Böning A, Koshty A. Endovascular treatment of the ascending aorta using a combined transapical and transfemoral approach. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67(2): 649–655. 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsieh YK, Lee CH. Experience of stent-graft repair in acute ascending aortic syndromes. J Card Surg. 2019;34(10):1012–1017. 10.1111/jocs.14181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zimpfer D, Czerny M, Kettenbach J, et al. Treatment of acute type A dissection by percutaneous endovascular stent-graft placement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82(2):747–749. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghoreishi M, Shah A, Jeudy J, et al. Endovascular repair of ascending aortic disease in high-risk patients yields favorable outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109:678–685. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senay S, Alhan C, Toraman F, Karabulut H, Dagdelen S, Cagil H. Endovascular stent-graft treatment of type A dissection: case report and review of literature. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34(4): 457–460. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palma JH. Endovascular treatment of chronic type A dissection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7(1):166. 10.1510/icvts.2007.165027a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metcalfe MJ, Karthikesalingam A, Black SA, Loftus IM, Morgan R, Thompson MM. The first endovascular repair of an acute type A dissection using an endograft designed for the ascending aorta. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(1):220–222. 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.06.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shabaneh B, Gregoric ID, Loyalka P, Krajcer Z. Complex endovascular repair of a large dissection of the ascending aorta in a 70-year-old man. Texas Hear Inst J. 2013;40(2):182–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pontes JC, Dias AM, Duarte JJ, Benfatti RA, Gardenal n. Endovascular repair of ascending aortic dissection. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2013;28(1):145–147. 10.5935/1678-9741.20130018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCallum JC, Limmer KK, Perricone A, Bandyk D, Kansal N. Case report and review of the literature total endovascular repair of acute ascending aortic rupture: a case report and review of the literature. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2013;47(5):374–378. 10.1177/1538574413486838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nienaber CA, Kische S, Rehders TC, et al. Rapid pacing for better placing: comparison of techniques for precise deployment of endografts in the thoracic aorta. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14(4): 506–512. 10.1583/1545-1550(2007)14[506:RPFBPC]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ueda T, Fleischmann D, Dake MD, Rubin GD, Sze DY. Incomplete endograft apposition to the aortic arch: bird-beak configuration increases risk of endoleak formation after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Radiology. 2010;255(2):645–652. 10.1148/radiol.10091468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sievers H-H, Rylski B, Czerny M, et al. Aortic dissection reconsidered: type, entry site, malperfusion classification adding clarity and enabling outcome prediction. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019;30:451–457. 10.1093/icvts/ivz281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fanelli F, Cannavale A, O’Sullivan GJ, et al. Endovascular repair of acute and chronic aortic type B dissections main factors affecting aortic remodeling and clinical outcome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(2):183–191. 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshitake A, Okamoto K, Yamazaki M, et al. Comparison of aortic arch repair using the endovascular technique, total arch replacement and staged surgery. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 2017;51(6): 1142–1148. 10.1093/ejcts/ezx028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanaoka Y, Ohki T, Maeda K, et al. Outcomes of chimney thoracic endovascular aortic repair for an aortic arch aneurysm. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;66:212–219. 10.1016/j.avsg.2018.12.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Melissano G, Tshomba Y, Bertoglio L, Rinaldi E, Chiesa R. Analysis of stroke after TEVAR involving the aortic arch. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43(3):269–275. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dumfarth J, Kofler M, Stastny L, et al. Stroke after emergent surgery for acute type A aortic dissection: predictors, outcome and neurological recovery. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 2018;53(5):1013–1020. 10.1093/ejcts/ezx465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams DM, Andrews JC, Victoria Marx M, Abrams GD. Creation of reentry tears in aortic dissection by means of percutaneous balloon fenestration: gross anatomic and histologic considerations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1993;4(1):75–83. 10.1016/S1051-0443(93)71824-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patel HJ, Williams DM, Meekov M, Dasika NL, Upchurch GR, Deeb GM. Long-term results of percutaneous management of malperfusion in acute type B aortic dissection: implications for thoracic aortic endovascular repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138(2): 300–308. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamman AV, Yang B, Kim KM, Williams DM, Michael Deeb G, Patel HJ. Visceral malperfusion in aortic dissection: the Michigan experience. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29(2):173–178. 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang B, Norton EL, Rosati CM, et al. Managing patients with acute type A aortic dissection and mesenteric malperfusion syndrome: a 20-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158(3):675–687. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.11.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang B, Rosati CM, Norton EL, et al. Endovascular fenestration/stenting first followed by delayed open aortic repair for acute type A aortic dissection with malperfusion syndrome. Circulation. 2018; 138(19):2091–2103. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Omura A, Matsuda H, Matsuo J, Kobayashi J. Endovascular repair of thrombosed-type acute type A aortic dissection with critical renal artery malperfusion. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 2018;54(6): 1142–1144. 10.1093/ejcts/ezy183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zubair MM, de Beaufort HWL, Belvroy VM, et al. Impact of cardiac cycle on thoracic aortic geometry – morphometric analysis of ECG gated computed tomography. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;65:1–9. 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.10.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Figueroa CA, Taylor CA, Yeh V, Chiou AJ, Gorrepati ML, Zarins CK. Preliminary 3D computational analysis of the relationship between aortic displacement force and direction of endograft movement. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(6):1488–1497. 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lam SK, Fung GSK, Cheng SWK, Chow KW. A computational study on the biomechanical factors related to stent-graft models in the thoracic aorta. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008;46(11):1129–1138. 10.1007/s11517-008-0361-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cook Medical Inc. Cook Zenith AlphaTM Thoracic Endovascular Graft. Instructions for Use. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cook Medical Inc. Zenith® TX2® TAA Endovascular Graft with Pro-FormTM and the Z-Trak® Plus Introduction System Two-Piece System. 2019.

- 71.Gore WL, Associates Inc. Instructions for Use GORE® TAG® Conformable Thoracic Stent Graft. 2019.

- 72.Medtronic Vascular Inc. Thoracic Stent Graft with the Captivia® Delivery System Instructions for Use. 2019.

- 73.Hughes GC. Stent graftiinduced new entry tear (SINE): intentional and NOT. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157(1):101–106. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.10.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bischoff MS, Müller-Eschner M, Meisenbacher K, Peters AS, Böckler D. Device conformability and morphological assessment after TEVAR for aortic type B dissection: a single-centre experience with a conformable thoracic stent-graft design. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2015;21:262–270. 10.12659/MSMBR.897010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sugawara J, Hayashi K, Yokoi T, Tanaka H. Age-associated elongation of the ascending aorta in adults. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008; 1(6):739–748. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hope MD, Hope TA, Crook SES, et al. 4D flow CMR in assessment of valve-related ascending aortic disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(7):781–787. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Youssefi P, Gomez A, He T, et al. Patient-specific computational fluid dynamics—assessment of aortic hemodynamics in a spectrum of aortic valve pathologies. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(1):8–20. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kilner PJ, Yang GZ, Mohiaddin RH, Firmin DN, Longmore DB. Helical and retrograde secondary flow patterns in the aortic arch studied by three-directional magnetic resonance velocity mapping. Circulation. 1993;88(5):2235–2247. 10.1161/01.CIR.88.5.2235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Figueroa CA, Taylor CA, Chiou AJ, Yeh V, Zarins CK. Magnitude and direction of pulsatile displacement forces acting on thoracic aortic endografts. J Endovasc Ther. 2009;16(3):350–358. 10.1583/09-2738.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tolenaar JL, Jonker FHW, Moll FL, et al. Influence of oversizing on outcome in thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Endovasc Ther. 2013;20(6):738–749. 10.1583/13-4388MR.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu L, Zhang S, Lu Q, Jing Z, Zhang S, Xu B. Impact of oversizing on the risk of retrograde dissection after TEVAR for acute and chronic type B dissection. J Endovasc Ther. 2016;23(4):620–625. 10.1177/1526602816647939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shimono T, Kato N, Yasuda F, et al. Transluminal stent-graft placements for the treatments of acute onset and chronic aortic dissections. Circulation. 2002;106(13_suppl):S241–S247. 10.1161/01.cir.0000032877.55215.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen Y, Zhang S, Liu L, Lu Q, Zhang T, Jing Z. Retrograde type A aortic dissection after thoracic endovascular aortic repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9):1–11. 10.1161/JAHA.116.004649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kreibich M, Rylski B, Kondov S, et al. Endovascular treatment of acute type A aortic dissection—the Endo Bentall approach. J Vis Surg. 2018;4(19):69. 10.21037/jovs.2018.03.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Felipe Gaia D, Bernal O, Castilho E, et al. First-in-human endo-Bentall procedure for simultaneous treatment of the ascending aorta and aortic valve. JACC Case Reports. 2020;2(3):480–485. 10.1016/j.jaccas.2019.11.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]