Abstract

Training programs have the dual responsibility of providing excellent training for their learners and ensuring their graduates are competent practitioners. Despite everyone’s best efforts a small minority of learners will be unable to achieve competence and cannot graduate. Unfortunately, program decisions for training termination are often overturned, not because the academic decision was wrong, but because fair assessment processes were not implemented or followed. This series of three articles, intended for those setting residency program assessment policies and procedures, outlines recommendations, from establishing robust assessment foundations and the beginning of concerns (Part One), to established concerns and formal remediation (Part Two) to participating in formal appeals and after (Part Three). With these 14 recommendations on how to get a grip on fair and defensible processes for termination of training, career-impacting decisions that are both fair for the learner and defensible for programs are indeed possible. They are offered to minimize the chances of academic decisions being overturned, an outcome which wastes program resources, poses patient safety risks, and delays the resident finding a more appropriate career path. This article (part one in the series of three) will focus on the foundational aspects of residency training and the emergence of concerns.

Abstract

Les programmes de formation ont la double responsabilité de fournir une excellente formation aux apprenants et de s’assurer qu’à l’issue de celle-ci les diplômés sont des praticiens compétents. Malgré tous les efforts déployés, une petite minorité d’apprenants ne parviendra pas à atteindre le niveau de compétence requis pour obtenir son diplôme. Malheureusement, la décision de la direction du programme de mettre fin à la formation d’un étudiant est souvent annulée, non pas parce qu’elle n’était pas académiquement fondée, mais parce qu’on a omis d’appliquer ou de suivre un processus d’évaluation juste. Cette série de trois articles, destinée aux responsables des politiques et procédures d’évaluation des programmes de résidence, présente des recommandations concernant l’établissement de bases d’évaluation solides et l’émergence de préoccupations quant à la progression d’un résident dans le programme (première partie), les préoccupations confirmées et la remédiation formelle (deuxième partie), et enfin le processus d’appel formel et ses suites (troisième partie). La mise en œuvre de ces 14 recommandations sur la définition de processus justes et légitimes pour mettre fin à la formation d’un apprenant devrait permettre de prendre des décisions aux répercussions importantes pour la carrière qui sont néanmoins à la fois justes envers la personne et justifiées du point de vue du programme. Elles sont proposées pour éviter la révision des décisions de nature académique, qui entraîne un gaspillage de ressources pour le programme, pose des risques pour la sécurité des patients et retarde la recherche d’un cheminement de carrière plus approprié pour le résident. Cette première partie de la série de trois articles se concentre sur les aspects fondamentaux de la formation en résidence et sur l’émergence de préoccupations.

Introduction

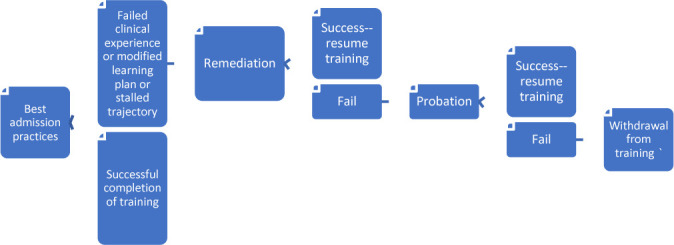

The two essential duties of postgraduate medical residency training programs are to provide the best possible training for their residents and to ensure their graduates are competent clinicians. For the purposes of this article, a clinician is defined as someone working within medicine providing direct patient care (medical, surgical, or laboratory medicine). Most residents successfully navigate the developmental steps needed to become independent practitioners. Some, despite the resident’s and program’s best intentions and efforts, do not. When that happens programs must fairly and compassionately terminate training. The usual steps leading to termination generally involve a number of opportunities for the resident to improve performance, starting with informal augmented learning plans through to formal remediation and probation (see Figure 1). Termination is complex, difficult, and often legally challenged. Termination decisions are often overturned, not because the academic decision was wrong, but because the resident was not afforded a fair process leading up to that decision. This results in the resident returning to training, which is difficult for all, time and resource-intensive, and a risk to patient safety. There is little in the literature to guide those responsible for establishing and upholding assessment practices to ensure fair and due assessment process, with much of that information coming from the United States.1-3 We have extensive, first-hand knowledge of legal challenges of most concern to program decisions to terminate training. KS is a former program director whose Canadian Family Medicine program embarked on CBME in 20104 and whose decisions over six years (2012-2018) to end training for six residents (out of a total of 425 residents) were all upheld. AR is the Faculty of Health Sciences lawyer who has an in-depth knowledge of program actions that either supported or weakened program decisions. LN is the educational institution’s internal review/appeal board’s lawyer and NS is the recording personnel for appeals, the last two authors having first-hand knowledge of the issues that were of most concern to review board members in coming to their decisions. This article is intended for program and site directors, postgraduate deans, and anyone else setting program assessment standards. This series of articles outlines 14 recommendations that are divided into five sections starting with A. Program Foundations followed by B. Beginnings of Concerns (Part One) C. Established concerns and Formal remediation/probation (Part Two)5 D. Legal challenges, and E. After the legal challenges (Part Three)6 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Typical Remediation/Probation pathway. In addition to this pathway based on repeated clinical performance issues, suspension may happen at any step along the way. Suspension occurs when there is a significant patient care issue or professionalism breach. Depending on the issue this may lead directly to residency termination or feed into the above pathway at any step along the way. A resident has a right to appeal any time along this pathway. Appeals generally have 3 increasingly formal tiers. The first appeal is generally at the residency program committee level, the second at the postgraduate dean level and the third at the dean or university senate level. Appeals must allow for the resident’s version of events to be heard. Legal representation almost always occurs at the third level of appeal and may occur sooner.

Table 1.

Summary of recommended steps for fair and defensible processes leading to termination of training

| Steps for fair and defensible processes leading to termination of residency training | Core concepts | |

|---|---|---|

| Part One | ||

| A. | Program Foundations: | |

| 1. | Ensure trustworthy assessment practices | Multiple expert assessors assessing the desired competencies using performance standards, doing this over time and contexts, documenting these assessments and having a system to interpret the collated data looking for patterns and trajectory |

| 2. | Ensure fair assessment practices | Clear relevant documented performance standards, opportunities for competency development, observation by informed assessors, clear feedback with ideas for improvement, followed by more opportunities for improvement |

| 3. | Provide holistic resident support | Evaluating for and attending to other factors that could be impacting resident performance |

| B. | Beginnings of Concerns: | |

| 4. | Make an educational diagnosis | Consideration of the situation holistically to determine the issue(s) negatively impacting clinical performance and addressing those |

| 5. | Bring concerns forward to an educational group | Separate informed body to review assessment data and any performance impacting factors to inform learning plans and summative decisions if need be |

| 6. | Start a documentation trail early | Documentation of all discussions and interventions pertaining to items 1-3, dated to create a timeline |

| Part Two | ||

| C. | Established Concerns | |

| 7. | Carefully create the remediation/probation plan | Use of an institutional template if available using deliberate unambiguous language with attention to practical and achievable interventions considering the reality of the workplace |

| 8. | Disseminate and review the plan with all involved. | Review of the plan with all involved ensuring program personnel (supervisors, education leaders) understand and can meet the requirements laid out in the plan and the resident has understood the plan and signed and dated each page as evidence of that understanding |

| 9. | Carryout the plan | Scrupulous attention to carrying out all elements of the plan. Support for all throughout |

| 10. | Determine the outcome | Outcome decision made by an independent assessment group |

| Part Three | ||

| D. | Challenges to program decisions: | |

| 11. | Preparation for the review | Review of all documentation and legal submissions and compiling evidence to justify the program decision |

| 12. | Participation in the review | Being adequately prepared for cross-examination both with documentation and mental mind set |

| E. | After the review. | |

| 13. | Improve program processes | Use of the review board’s findings to improve any weaknesses in assessment processes |

| 14. | Support the learner. | Career counselling if training is terminated |

It is the norm for Canadian institutions to have an internal institutional legal appeal protocol that gives residents the right to have an adverse decision reviewed by a neutral third party (hereafter called a review board; personal communication). This article is based on the assumption that programs have a review board in place.

A. Program foundations

Programs must provide learning opportunities designed to support development of the desired competencies and then assess for relevant/authentic outcomes. Assessment processes must be reliable/trustworthy as well as transparent and fair for residents. In addition, programs should also support their residents in a holistic way to help them achieve their maximum potential.

Recommendation 1: ensure trustworthy assessment practices

Trustworthy assessment practices will position review boards to accept your academic decision and narrow their focus on a fair process for the resident. Particularly scrutinized will be the trustworthiness of the workplace-based assessment (WBA) inherent in competency-based medical education. WBA of residents carrying out their clinical duties, based on decisions by assessors observing and assessing resident’s clinical performance, will involve a degree of subjectivity. This is true whether the tool used to record that assessment converts this assessment to a quantitative number or category or records this as a qualitative comment.

Strategies to ensure trustworthiness, given this subjectivity, are important and essentially involve two principles:7-10

multiple expert assessors who understand the competencies and standards of performance expected of residents and are willing to observe resident performance and frequently document informative low-stakes assessment about those competencies over time. This reduces the risk of individual biases and allows for triangulation of opinion about competency development.11,1,2

a robust system of collation and interpretation of those low-stakes assessments, identifying patterns of performance and trajectory of development to make summative decisions.

Depending on the make-up of the review board, education about the more qualitative nature of WBA and why this is better suited to competency assessment in the clinical setting than the more quantitative tests used to in other settings, may be a necessary part of your program’s submissions during the review.

Recommendation 2: ensure fair assessment practices

This involves:

having reasonable competencies and standards of performance that are explicitly and demonstrably articulated to residents. Making sure a resident has been given the opportunity to understand these expectations throughout the assessment process is often a key focus of review tribunals;

using the trustworthy processes previously mentioned to measure residents against the standards;

providing opportunities for the resident to build those competencies;

direct observation;

unambiguous, timely, meaningful and substantive feedback outlining strengths and areas for development (preferably both verbally and in writing), and clearly articulating those that will require improvement for training to be successful. This point cannot be overemphasized: assessments, while they should be supportive rather than discouraging, cannot be vague;

opportunities for residents to voice their opinion and seek clarifications;

instruction on how improve performance

repeated cycling of the above.

The more significant or impactful the decision, the greater scrutiny on fairness of process, and there is nothing more significant or impactful on a resident than terminating their training. Processes must be in place to ensure a high level of fairness in the process, and you must be able to demonstrate that in the event of a review.

Recommendation 3: provide holistic resident support

In addition to sound assessment practices, all residents should be supported for success. In addition to offering developmental opportunities consider other issues that may affect their progress. Do they need counselling, time off to pursue this before resuming training, a modified part-time residency, extra recovery and/or study time between shifts, or accommodations to address disabilities? Has there been an exploration as to whether this resident’s aptitudes are best suited for this area of medicine? Is an exploration of a transfer to another program warranted? Having a process where residents’ well-being is regularly reviewed, and issues are responded to is part of a strong foundation for optimizing residents’ competency development.

B. Beginnings of concerns

As assessment data start to accumulate patterns of concerning performance and/or a very slow trajectory may start to emerge for some residents. At that point:

Recommendation 4: make an educational diagnosis

You will want to determine what factor or factors are negatively impacting the resident’s competency development. This educational diagnosis requires a systematic deliberate approach. You will need to consider numerous contributors including learner factors of knowledge deficits, cognitive issues, attitudinal contributors, personal life issues, as well as issues outside the learners control including preceptor and environmental/system issues.1,3 With that diagnosis you may adjust training and/or provide resources to address these factors. Whenever an approach to an individual deviates from that used for the majority, you can expect to face a legal argument that the outcome of their modified educational plan was a foregone conclusion, with no possibility of remediation or success. Documenting what was considered and why changes made were for resident success and/or patient safety will be helpful for review boards to dismiss this concern.

Recommendation 5: bring concerns forward to an educational group (e.g. a competency committee or post-graduate education committee)

Like a clinical review board considering a difficult clinical situation, bringing forward a difficult educational situation to an impartial group affords the benefit of several people providing input (i.e. reassessing the educational diagnosis and considering best way to individualize a learning plan to maximize the support and opportunities for the resident). It is also part of a fair assessment process. Important career-impacting decisions must never be the result of a single individual’s opinion but should be subjected to neutral third-party review of available data for substance and process.

Recommendation 6: start a documentation trail early

Document around the above three pillars of robust assessment, fair assessment, and support for the resident. The review board should be able to read illustrative documentation and come to their own decisions about each of these three pillars. In addition, meetings with the resident and preceptor(s) and program leaders should be documented. Short, dated meeting summaries, done as soon as possible after the meeting, lets the review board follow the course of events and see that everyone was informed. They are also invaluable as aide memoires when preparing for a review board hearing. Remember that all communication becomes a part of a record that can, and likely will be, subpoenaed. In most jurisdictions, emails, texts, written communication, meeting summaries, and committee minutes are very often accessible through Freedom of Information legislation. Everyone involved must know this and pay attention to wording all communication, even those not directly sent to the resident, professionally and without editorializing or venting emotion. “Write it as if a court will read it” is good advice.

Conclusion

The first three recommendations have outlined program foundations that should be in place for all residents. Most residents can progress as expected in their competency development with these functioning properly. A small number of residents may struggle. Recommendations 4-6 discuss working with these residents to determine the issues impacting performance and personalizing support for them. These will help many residents return to an acceptable competency development trajectory. A small number of residents however, despite these efforts, will not meet their milestones. At that point formal remediation should commence. This will be the topic of Part Two in this series.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this work

References

- 1.Schenarts PJ, Langenfeld S. The fundamentals of resident dismissal. Am Surg, 2017; 83(2): 119-126. 10.1177/000313481708300210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minicucci RF, Lewis BF. Trouble in academia: Ten years of litigation in medical education. Acad Med. 2003; 78(10): S13-S15. 10.1097/00001888-200310001-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tulgan H, Cohen SN, KInne KM. How a teaching hospital implemented its termination policies for disruptive residents. Acad Med. 2001; 76 (11): 1107-1112. 10.1097/00001888-200111000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz KW, Griffiths J. Implementing competency-based medical education in a postgraduate family medicine residency training program: a stepwise approach, facilitating factors and processes or steps that would have been helpful. Acad Med. 2016; 91: 685-689. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz K, Risk A, Newton L, Snider N. Formal remediation and probation (part two of 3) When residents shouldn’t become clinicians: Getting a grip on fair and defensible processes for termination of training. Can Med Ed J. 2021. 10.36834/cmej.72735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultz K, Risk A, Newton L, Snider N. The appeal process and beyond (part three of 3) When residents shouldn’t become clinicians: Getting a grip on fair and defensible processes for termination of training Can Med Ed J. 2021. 10.36834/cmej.72736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, Swing SR, Frank JR. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2010; 32:676-82. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Driessen EW, et al. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med Teach. 2012; 34:205-214. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.652239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hays RB, Hamlin G, Crane L. Twelve tips for increasing the defensibility of assessment decisions. Med Teach.2015; 87:433-436. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.943711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norcini J, Anderson MB, Bollela V, et al. 2018 Consensus framework for good assessment. Med Teach. 2018; 40: 1102-1109. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1500016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeates P, O’Neill P, Mann K, Eva K. Seeing the same thing differently: Mechanisms that contribute to assessor differences in directly-observed performance assessments. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2013; 18:35-341. 10.1007/s10459-012-9372-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ten Cate O, Regehr G. The power of subjectivity in the assessment of medical trainees. Acad Med. 2019; 94(3): 333-337. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacasse M, Audetat MC, Boileau E, et al. Interventions for undergraduate and postgraduate medical learners with academic difficulties: A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 56. Med Teach. 2019; 41 (9): 981-1001. 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1596239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]