Abstract

Mushroom-derived cyathane-type diterpenes possess unusual chemical skeleton and diverse bioactivities. To efficiently supply bioactive cyathanes for deep studies and explore their structural diversity, de novo synthesis of cyathane diterpenes in a geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae is investigated. Aided by homologous analyses, one new unclustered FAD-dependent oxidase EriM accounting for the formation of allyl aldehyde and three new NADP(H)-dependent reductases in the biosynthesis of cyathanes are identified and elucidated. By combinatorial biosynthetic strategy, S. cerevisiae strains generating twenty-two cyathane-type diterpenes, including seven “unnatural” cyathane xylosides (12, 13, 14a, 14b, 19, 20, and 22) are established. Compounds 12–14, 19, and 20 show significant neurotrophic effects on PC12 cells in the dose of 6.3–25.0 μmol/L. These studies provide new insights into the divergent biosynthesis of mushroom-originated cyathanes and a straightforward approach to produce bioactive cyathane-type diterpenes.

KEY WORDS: Cyathane-type diterpene, Biosynthesis, Heterologous expression, Non-enzymatic reaction

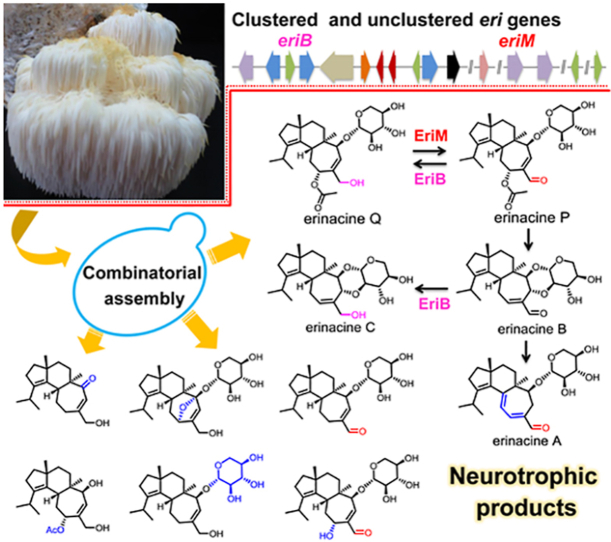

Graphical abstract

Cyathane diterpens are lead compounds for neurodegenerative diseases. This work convenes the de novo synthesis of twenty-two cyathane derivatives. A key and unclustered FAD-dependent oxidase was elucidated for the biosynthesis of erinacines.

1. Introduction

Cyathanes refer to a class of unique and mushroom-derived natural products possessing an angularly fused 5/6/7 tricyclic skeleton1,2. Basidiomycetes including Hericium, Cyathus, Sarcodon, Phellodon, Strobilurus, and Laxitextum species were reported to produce cyathane analogues with a broad spectrum of biological activities3. Erinacine A (1) possessing a rare cyclohepta-1,3-diene feature and notable potential to conquer neurodegenerative diseases was isolated from Hericium erinaceus4,5. Treatment with erinacine A exhibited beneficial effects on neurons, such as inhibiting the ROS-mediated neuron inflammation and death pathway6, activating neuronal survival pathway7, enhancing the synthesis of nerve growth factor8, and promoting NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in nerve cells9.

To ensure a sustainable supply of cyathanes for bioactivity investigation, chemists endeavoured to develop different total synthetic routes10, 11, 12. However, the currently reported approaches with harsh conditions and low yields were not amiable in industry. Recently, genetically engineered microbes had been successfully adopted for producing valuable natural products (such as opioids, artemisinic acid, and ganoderic acid)13, 14, 15, which provides alternative strategy for the production of cyathanes. In our early work, we identified the gene cluster containing EriE (geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase), EriG (UbiA-type terpene synthase), EriA/C/I (three P450 hydroxylases), and EriJ (glycosyltransferase) in H. erinaceus and characterized the function of EriG catalyzing the formation of the cyathane skeleton (Fig. 1)16. Genome mining among basidiomycetes revealed another three similar clusters with eri, including rim cluster from Rickenella mellea, cya cluster from Cyathus striatus, and bom cluster from Bondarzewia mesenterica. In the following work, Liu et al.17 demonstrated the catalytic functions of eriA, C, H, I, and J together with an unclustered acetyl transferase EriL for the acetylation at 11-OH by heterologous expression in Aspergillus oryzae (Fig. 2). However, the production yields of cyathanes in A. oryzae is unsatisfactory. On the other hand, the gene responsible for the biosynthesis of α,β-unsaturated aldehyde group in cyathanes remains unknown. In the reported cyathanes, the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde group was not only the important structural feature of bioactive cyathane-type diterpenes, such as eriancine A (1), erinacine B (2), and erinacine P (3), but also accounted for the formation of C–C or C–O bond between xylose unit and cyathane aglycone as exemplified by striatoid C (4) and erinacine E (5) (Fig. 1A)18, 19, 20.

Figure 1.

Representative structures of cyathanes (A), and the eri genes with their homologous (B).

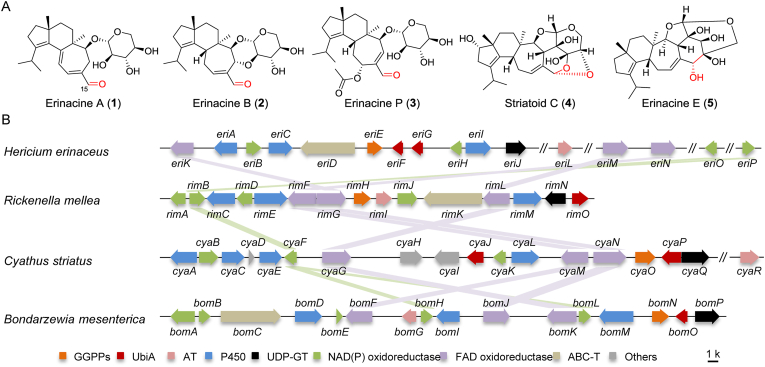

Figure 2.

The modular biosynthetic pathway of erinacines. Arrows in red indicate the non-natural process in the formation of erinacines.

In this study, we identified an unclustered FAD-dependent oxidase EriM responsible for the formation of allyl aldehyde in erinacines, demonstrated the allyl aldehyde-triggered nonenzymatic reactions in the biosynthesis of erinacines A‒C. Furthermore, combinatorial biosynthetic routes leading to the de novo synthesis of 22 cyathanes were established in a geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP)-engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

2. Results

2.1. Divergent biosynthetic pathway for cyathanes derivatives

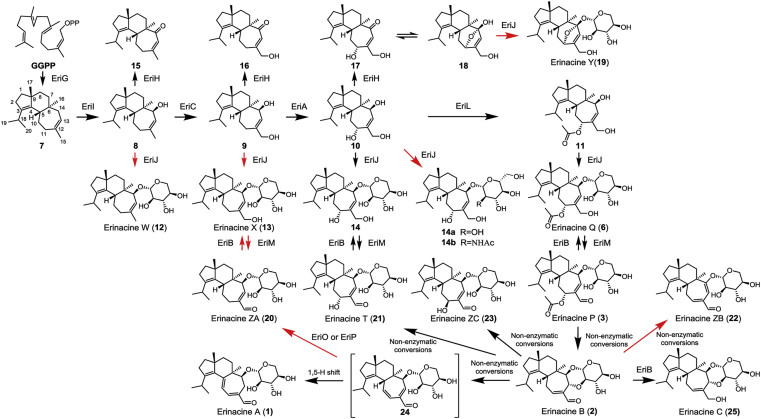

In the early report, heterologous expression of biosynthetic genes for erinacine Q (6) in A. oryzae generated a transformant strain with a low titer of 4.7 mg/L17. Thus, our first goal was to design an efficiency biocatalyst system to produce 6 with satisfactory yield in an engineered S. cerevisiae BY-T20, which had been engineered with high profit of GGPP21. The eri genes were introduced into δ sites or rDNA sites on the chromosome of S. cerevisiae with yeast promoters and terminators (Supporting Information Table S1) by homologous recombination. The cDNA of eriG was first integrated into yeast chromosome at the δ locus with PFBA1 promoter and TADH1 terminator to give the transformant SC-G and produce cyatha-3,12-diene (7) at a level of 105.8 mg/L (Fig. 3). Then, ncpr1 (encoding for a NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase in S. cerevisiae)22, which was amplified from the genomic DNA of S. cerevisiae BY-T20, and eriI were co-expressed with eriG in the strain BY-T20. The resulting strain SC-GI produced a C-14 hydroxylated product (8, 79.3 mg/L). Similarly, transformants SC-GIC, SC-GICA, SC-GICAL, and SC-GICALJ were constructed. Genes eriG/eriI/ncpr1 were integrated into δ sites, while genes AtUGD123, AtUXS323, and eriJ/C/A/L were introduced into rDNA sites of yeast chromosome. HPLC analysis of the broth extracts from these transformants showed the synthesis of 9‒11 and erinacine Q (6) with the titers of 112.1, 88.5, 82.8, and 90.9 mg/L, respectively (Fig. 3 and Supporting Information Table S2).

Figure 3.

HPLC analyses of transformants expressing different biosynthetic enzymes.

In vitro enzymatic assays demonstrated that glycosyltransferase EriJ accepted 8–10 as substrates to catalyze the xylosylation of 14-OH and give the corresponding products 12–14 (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Thus, strains SC-GIJ, SC-GICJ, and SC-GICAJ were created and detected the synthesis of 12‒14 with concentrations of 84.1, 100.3, and 98.4 mg/L (Fig. 3). In addition, the sugar nucleotide specificity test showed that EriJ could accept UDP-glucose and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine as donors, thus converting 10 into 14a and 14b, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Compounds 14a and 14b were successfully detected and isolated from the transformant SC-GICAJ (Supporting Information Tables S3 and S4).

Meanwhile, we generated transformants for the production of 15, 16, and cyathin A3 (a mixture of 17 and 18) by incorporating the EriH, a NAD/NADP-binding oxidase, into strains SC-GI, SC-GIC, and SC-GICA (Fig. 3). In the following, we transformed eriH-carrying plasmid into SC-GICAJ to generate a strain SC-GICAJH and obtained 19. In vitro enzymatic assays also confirmed that EriH accepted 8–10 as substrates (Supporting Information Fig. S3). Erinacines W (12), X (13), and Y (19) are new unnatural caythane-xylosides. All compounds obtained from transformants were characterized by MS and NMR analyses (Table 1, Table 2)24, 25, 26, 27, 28. Collectively, these results strongly supported that divergent tailoring pathway in the biosynthesis of mushroom-originated cyathanes.

Table 1.

1H and13C NMR data of 12, 13, and 19 in 500 MHz.

|

12a |

13 |

19 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | δC | δH mult. (J in Hz) | No. | δC | δH mult. (J in Hz) | No. | δC | δH mult. (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 39.2 | 1.58, m 1.51, (overlapped) |

1 | 37.7 | 1.51, m 1.46 (overlapped) |

1 | 39.0 | 1.48 (overlapped) 1.40 (overlapped) |

| 2 | 29.3 | 2.30 (overlapped) | 2 | 27.8 | 2.22, t (7.6) | 2 | 26.2 | 1.22 (overlapped) 1.40 (overlapped) |

| 3 | 140.0 | – | 3 | 139.7 | – | 3 | 138.2 | – |

| 4 | 141.3 | – | 4 | 138.0 | – | 4 | 136.7 | – |

| 5 | 44.6 | 2.94, d (11.8) | 5 | 43.1 | 2.88, d (11.4) | 5 | 41.3 | 2.34, d (11.0) |

| 6 | 44.6 | – | 6 | 42.8 | – | 6 | 47.7 | – |

| 7 | 34.2 | 2.21 (overlapped) 1.14 (overlapped) |

7 | 32.6 | 1.02 (overlapped) 2.19 (overlapped) |

7 | 29.6 | 2.19 (overlapped) |

| 8 | 38.1 | 1.51 (overlapped) 1.41, ddd (12.9, 4.7, 2.6) |

8 | 36.8 | 1.41 (overlapped) 1.33, m |

8 | 36.9 | 1.61 (overlapped) 1.36, m |

| 9 | 50.5 | – | 9 | 49.1 | – | 9 | 47.7 | – |

| 10 | 27.2 | 1.92 (overlapped) 1.08, m |

10 | 26.0 | 1.80, m 1.71, m |

10 | 28.4 | 2.03, t (12.7) 1.48 (overlapped) |

| 11 | 33.9 | 2.57, dd (14.6, 10.8) 1.98 (overlapped) |

11 | 28.1 | 2.37, m 1.87 (overlapped) |

11 | 77.5 | 4.64, br |

| 12 | 142.1 | – | 12 | 143.7 | – | 12 | 148.7 | – |

| 13 | 125.6 | 5.52, d (6.9) | 13 | 123.1 | 5.60, d (6.8) | 13 | 123.2 | 5.99, s |

| 14 | 87.7 | 3.59, d (6.9) | 14 | 84.6 | 3.56, d (6.8) | 14 | 112.8 | – |

| 15 | 26.0 | 1.74, s | 15 | 65.3 | 3.76, d (5.0) | 15 | 57.0 | 4.08 (overlapped) |

| 16 | 17.4 | 0.83, s | 16 | 16.4 | 0.73, s | 16 | 11.9 | 0.91, s |

| 17 | 25.0 | 1.10, s | 17 | 24.5 | 1.04, s | 17 | 24.0 | 0.91, s |

| 18 | 28.1 | 3.06, dd (6.8) | 18 | 26.3 | 2.98 (overlapped) | 18 | 25.7 | 2.91 (overlapped) |

| 19 | 22.0 | 0.98, dd (11.2, 6.8) | 19 | 21.9 | 0.92, d (6.7) | 19 | 22.4 | 0.97, d (6.7) |

| 20 | 22.3 | 0.98, dd (11.2, 6.8) | 20 | 21.6 | 0.91, d (6.7) | 20 | 21.1 | 0.87, d (6.7) |

| 1′ | 107.0 | 4.27, d (7.0) | 15-OH | – | 4.73, t (5.5) | 15-OH | – | 4.98, t (5.4) |

| 2′ | 75.3 | 3.26, dd (8.8, 7.0) | 1′ | 105.8 | 4.13, d (7.3) | 1′ | 97.2 | 4.43, d (7.4) |

| 3′ | 77.7 | 3.32 (overlapped) | 2′ | 73.8 | 3.02 (overlapped) | 2′ | 73.0 | 2.98 (overlapped) |

| 4′ | 71.2 | 3.48, ddd (9.6, 8.3, 5.1) | 2′-OH | – | 4.95, d (5.5) | 2′-OH | – | 4.50, d (5.0) |

| 5′ | 66.6 | 3.83, dd (11.5, 5.1) 3,16, dd (11.6, 9.6) |

3′ | 76.5 | 3.10, m | 3′ | 76.3 | 3.09, m |

| 3′-OH | – | 4.87, d (4.6) | 3′-OH | – | 4.91, d (4.7) | |||

| 4′ | 69.5 | 3.26, m | 4′ | 69.4 | 3.27, m | |||

| 4′-OH | – | 4.90, d (5.0) | 4′-OH | – | 4.91, d (4.7) | |||

| 5′ | 65.5 | 2.98 (overlapped) 3.62, dd (11.3, 5.2) |

5′ | 65.4 | 2.94 (overlapped) 3.68, dd (11.3, 5.2) |

|||

12 was tested in methanol-d4, 13 and 19 were tested in DMSO-d6.

Table 2.

1H and13C NMR data of 20, 22, and 23 (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz).

|

20 |

22 |

23 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | δC | δH mult. (J in Hz) | No. | δC | δH mult. (J in Hz) | No. | δC | δH mult. (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 37.5 | 1.51 (overlapped) 1.47 (overlapped) |

1 | 36.5 | 1.55 (overlapped) 1.50 (overlapped) |

1 | 37.3 | 1.47 (overlapped) |

| 2 | 28.1 | 2.23, t (7.6) | 2 | 27.9 | 2.27, t (7.1) | 2 | 28.3 | 2.25, t (7.8) |

| 3 | 138.9 | – | 3 | 139.6 | – | 3 | 138.5 | – |

| 4 | 138.7 | – | 4 | 137.7 | – | 4 | 139.0 | – |

| 5 | 42.4 | 2.87, br | 5 | 42.4 | 2.54, t (6.0) | 5 | 35.1 | 3.28 (overlapped) |

| 6 | 43.0 | – | 6 | 48.3 | – | 6 | 43.6 | – |

| 7 | 32.2 | 1.18, m 2.15, m |

7 | 33.6 | 1.63, td (13.8, 4.0) 1.77, dt (13.8, 4.0) |

7 | 32.3 | 1.46 (overlapped) 1.14, br |

| 8 | 25.0 | 1.45 (overlapped) 1.35, m |

8 | 34.8 | 1.41, td (12.7, 4.0) 1.26, dt (12.7, 4.0) |

8 | 36.2 | 1.51 (overlapped) 1.37, dt (12.3, 3.5) |

| 9 | 49.0 | – | 9 | 49.5 | – | 9 | 49.3 | – |

| 10 | 25.0 | 1.78 (overlapped) 1.72 (overlapped) |

10 | 30.2 | 2.78, t (6.0) | 10 | 33.5 | 1.98, m |

| 11 | 21.8 | 2.35, m 2.50 (overlapped) |

11 | 151.7 | 6.88, t (6.0) | 11 | 61.3 | 4.63, br |

| 12 | 144.1 | – | 12 | 136.4 | – | 12 | 145.9 | – |

| 13 | 154.2 | 6.88, d (6.6) | 13 | 92.4 | 5.81, s | 13 | 153.8 | 6.95, d (7.0) |

| 14 | 83.9 | 3.91, d (6.6) | 14 | 168.6 | – | 14 | 83.3 | 3.93, d (7.0) |

| 15 | 194.2 | 9.39, s | 15 | 193.4 | 9.27, s | 15 | 194.1 | 9.38, s |

| 16 | 15.9 | 0.76, s | 16 | 18.5 | 1.11, s | 16 | 15.6 | 0.72, s |

| 17 | 24.4 | 1.04, s | 17 | 23.9 | 0.95, s | 17 | 24.3 | 1.08, s |

| 18 | 26.4 | 2.92 (overlapped) | 18 | 26.6 | 2.92, m | 18 | 26.4 | 2.95, m |

| 19 | 21.6 | 0.91, d (6.7) | 19 | 21.9 | 1.01, d (6.7) | 19 | 21.9 | 0.93, d (7.2) |

| 20 | 21.6 | 0.90, d (6.7) | 20 | 21.2 | 0.97, d (6.7) | 20 | 21.6 | 0.92, d (7.2) |

| 1′ | 105.8 | 4.19, d (7.3) | 1′ | 101.0 | 4.51, d (6.8) | 1′ | 105.4 | 4.32, d (6.6) |

| 2′ | 73.5 | 3.04 (overlapped) | 2′ | 72.9 | 3.15 (overlapped) | 2′ | 73.0 | 3.06 (overlapped) |

| 2′-OH | – | 5.08, d (5.6) | 3′ | 76.3 | 3.17 (overlapped) | 3′ | 75.0 | 3.17, m |

| 3′ | 76.4 | 3.12, m | 4′ | 69.3 | 3.34, m | 4′ | 69.2 | 3.28 (overlapped) |

| 3′-OH | – | 4.91, d (4.9) | 5′ | 65.5 | 3.13 (overlapped) 3.77, dd (11.3, 5.2) |

5′ | 65.0 | 3.68, dd (11.5, 4.7) 3.09 (overlapped) |

| 4′ | 69.5 | 3.26, m | ||||||

| 4′-OH | – | 4.92, d (5.2) | ||||||

| 5′ | 65.6 | 3.02 (overlapped) 3.62, dd (11.3, 5.2) |

||||||

2.2. Discovery of unclustered oxidoreductases in the genome of H. erinaceus

After generating erinacine Q (6), 13, and 14 in yeast, we proceeded to identify the enzyme responsible for aldehydation at C-15. Fungal FAD-dependent oxidoreductases were demonstrated to catalyze the formation of aldehyde in biosynthesis of solanapyrone A and glycine betaine29,30. Thus, we generated the transformant co-expressing eriG/I/C/A/L/J with the FAD-dependent oxidoreductase encoded gene eriK. The obtained strain SC-GICALJK failed to synthesis erinacine P (3) (Supporting Information Fig. S4), thus suggesting a potential unclustered gene for such reaction.

Next, we searched for FAD-dependent oxidoreductase genes in the rim cluster from R. mellea, cya cluster from C. striatus, and bom cluster from B. mesenterica. Cyathane-type diterpenes have been reported from the mushroom C. striatus31. As a result, two conservative FAD-dependent oxidase genes in the rim (rimF and rimL), cya (cyaG and cyaM), and bom (bomF and bomK) cluster, were discovered, respectively (Fig. 1B and Supporting Information Table S5). With RimF and RimL as query sequences, two homologous proteins EriM with 65.6% dentity of RimL and EriN with 67.8% identity of RimF were identified from H. erinaceus. Similarly, additional two unclustered NAD(P)/NAD(P)H oxidoreductases (EriO and EriP) with 55%–78% sequence identities of RimB, CyaF, BomH, and BomL were also found in the genome of H. erinaceus (Fig. 1B and Table S5).

2.3. Identification of catalytic functions of EriM and EriN

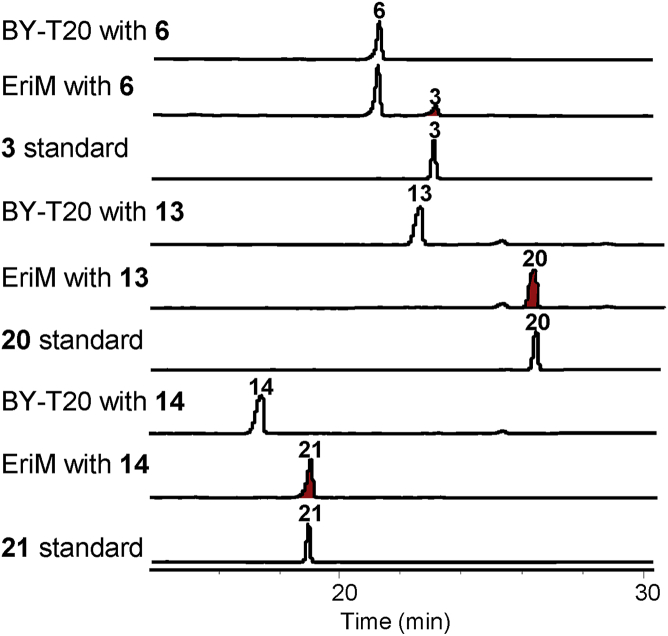

To determine the functions of eriM and eriN, transformants SC-GICJM, SC-GICJN, SC-GICAJM, SC-GICAJN, SC-GICALJM, and SC-GICALJN were constructed. HPLC analyses showed the synthesis of metabolites 20 and erinacine T (21) and the formation of erinacine P (3) in the strains SC-GICJM, SC-GICAJM, and SC-GICALJM, respectively (Fig. 3). Compound 20 was a new cyathane-type diterpene whose structure was determined by HR‒MS and NMR data analysis. Accordingly, the function of EriM was deduced to catalyze the oxidation of the allyl alcohol. To further verify the catalytic function of EriM, substrates 6, 13, and 14 were fed to the transformant SC-M bearing expression plasmid of pESC-TRP-EriM, respectively. As a result, the corresponding oxidation products 3, 15, and 16 (Fig. 4) were obtained, which definitely confirmed the oxidizing function of EriM on allyl alcohol (Fig. 2). However, no products were detected in the culture of the transformant SC-M when fed with different substrates 9, 10, 11, 16 and 17.

Figure 4.

Feeding experiments of EriM with substrates 6, 13, and 14 by using BY-T20 as a control strain. Compounds were detected at 210 nm.

2.4. Revealing non-enzymatic spontaneous reaction in the formation of erinacines A (1), B (2), T (21), and ZC (23)

To our surprise, besides 3, the transformant SC-GICAJLM produced another three metabolites 1, 22, and 23. After a large scale fermentation of SC-GICAJLM, we successfully obtained compounds 1 (30.5 mg), 22 (5.8 mg), and 23 (2.5 mg). Further HRTOF-MS and NMR analyses assigned 1 to be erinacine A4. The HRTOF-MS and 1D NMR data of 22 indicated a similar structure with that of 1. The main differences between 1 and 22 lie in the chemical shifts of olefinic protons (δH 6.79, d, J = 8.0 Hz and 5.78, d, J = 8.0 Hz in 1; δH 6.88, t, J = 6.0 Hz and 5.81, s in 22) (Table 2). The HMBC correlations from H-11 (δH 6.88) to C-5/C-10/C-13/C-15 and H-13 to C-6/C-11/C-12/C-14/C-15 determined the cyclohepta-1,6-diene-1-carbaldehyde moiety in 22 (Fig. 2). Compound 23 was identified to be an epimer of 21 by 2D NMR data analysis (Table 2). The HMBC correlations from H-11 to C-5/C-10/C-12/C-13/C-15 and NOE correlations from H-11 to H-14 confirmed a β-hydroxyl group at C-11 in 23.

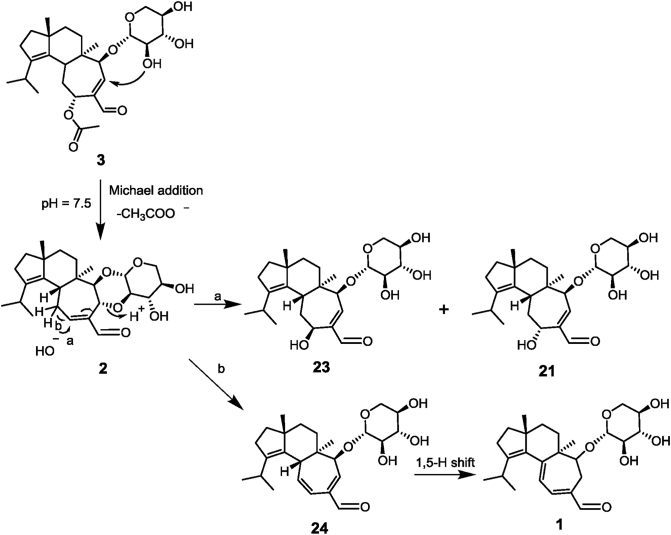

Kenmoku et al.18 reported the chemical transformation of 3 to 1 via 2 by sequential Michael addition–elimination, which in combination with the co-existence 1 and 3 in the transformant SC-GICAJLM proposed the non-enzyme reaction in the formation of 1. To test our hypothesis, strains SC-M and BY-T20 were fed with 3, respectively. HPLC analysis of broth extracts showed the conversion of 3 to 1 (yield 29%), 21 (yield 4%), and 22 (yield 2%) (Supporting Information Fig. S5), supporting the occurrence of spontaneous reactions. Further in vitro incubation of 3 in buffer solution (pH = 7.5, the pH value at endpoint of fermentation) at 28 °C resulted in the formation of 1, 2, and 21 (Supporting Information Fig. S6). Additionally, it was found that high temperature and high pH facilitated the formation of 2 and the transformation from 2 to 1 and 21 (Supporting Information Fig. S7). Compound 2 was produced in advance of 1 in the solution. Thus, 2 was purified from the mixture of 3 incubated in an optimized condition. Furthermore, compound 2 was found to be converted into 1, 21, and 23 under the same condition (Supporting Information Fig. S8). These results demonstrated the FAD oxidase-driven and spontaneous Michael addition–elimination reactions in the biosynthesis of erinacines A (1), B (2), T (21), and ZC (23) from erinacine P (3) (Scheme 1). The formation mechanism of 22 in both strains SC-M and BY-T20 deserves further study.

Scheme 1.

Mechanisms for spontaneous synthesis of 1, 21, and 23 from 3via2.

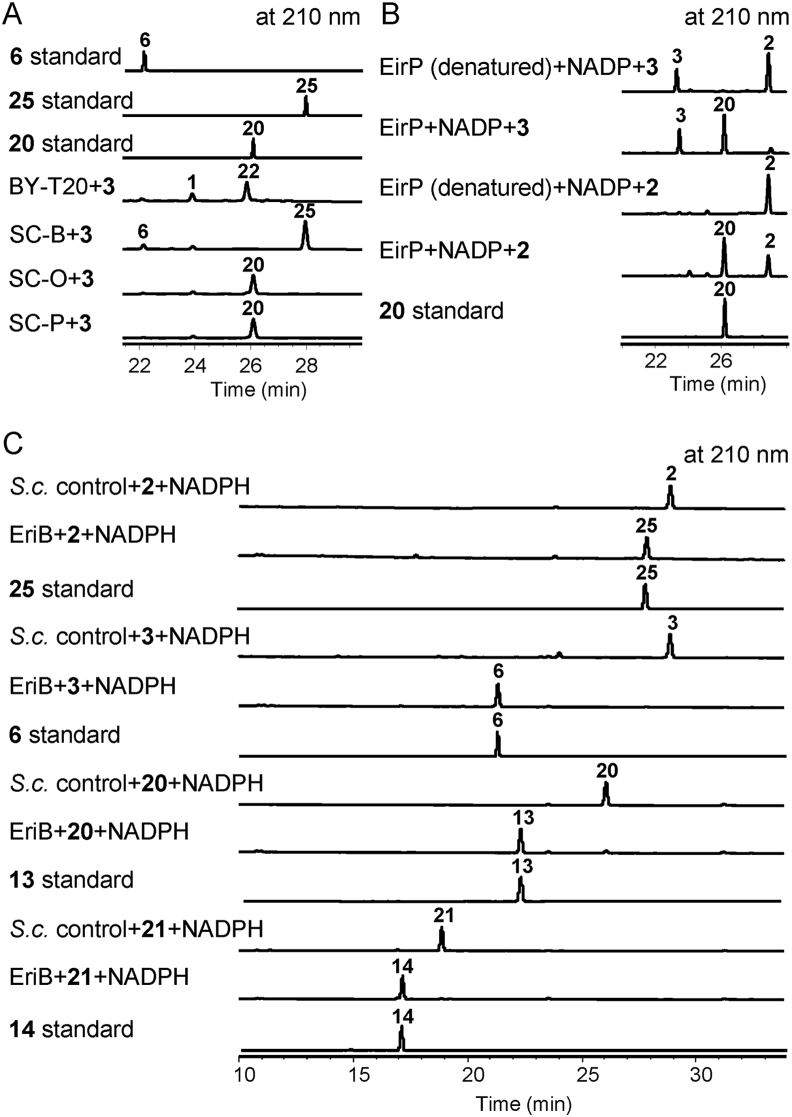

2.5. Generation of erinacine C and functions of EriP and EriO

Next, to corroborate the functions of three unsolved NAD(P)/NAD(P)H oxidoreductases EriB, EriO, and EriP, strains SC-B, SC-O, and SC-P were created by introducing the plasmids pESC-TRP-EriB, pESC-TRP-EriO, and pESC-TRP-EriP into BY-T20, respectively. Feeding experiments with 3 revealed that strain SC-B transformed 3 into 6 and 25 (Fig. 5) that was determined to be erinacine C by NMR data comparison with the published values4. Next, the engineered stain SC-GICALJMB expressing eriG/I/C/A/L/J/M/B produced 25 with a yield of 43.6 mg/L (Fig. 3A). Our attempt to purify EriB in yeast was unsuccessful. To definitely confirm the function of EriB, microsome of EriB was prepared by the reported method32. Incubation of EriB microsome with 2, 3, 20, and 21 in the presence of NADPH generated the corresponding reducing products 25, 6, 13, and 14, respectively (Fig. 5C). Based on these results, EriB was defined as an NADPH reductase catalyzing the reduction of allyl aldehyde. For the strains of SC-O and SC-P, feeding experiments with 3 gave the same metabolite 20 (Fig. 5). Purification of EriP in yeast was successful while the attempt to purify EriO was failed. Further in vitro enzymatic reactions using purified EriP with 2 or 3 as substrate gave the same product 20 in the presence of NADP (Fig. 5B). Postulating 24 as the key intermediate for the spontaneous transformation from 2 or 3 to 1, we supposed it as the true substrate of EriO and EriP.

Figure 5.

HPLC analysis for products of EriB, EriO, and EriP. (A) Feeding experiments of SC-B, SC-O, and SC-P with 3. (B), In vitro enzymatic reactions of EriP with 2 and 3. (C), In vitro assay of EriB (microsome) with 2, 3, 20, and 21 as substrates.

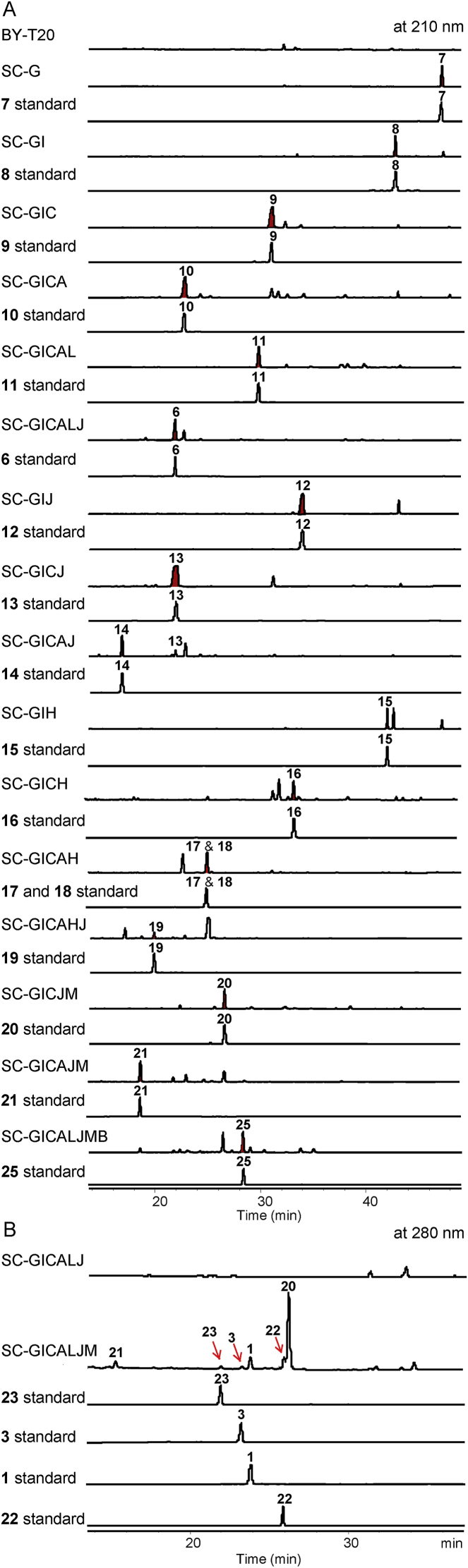

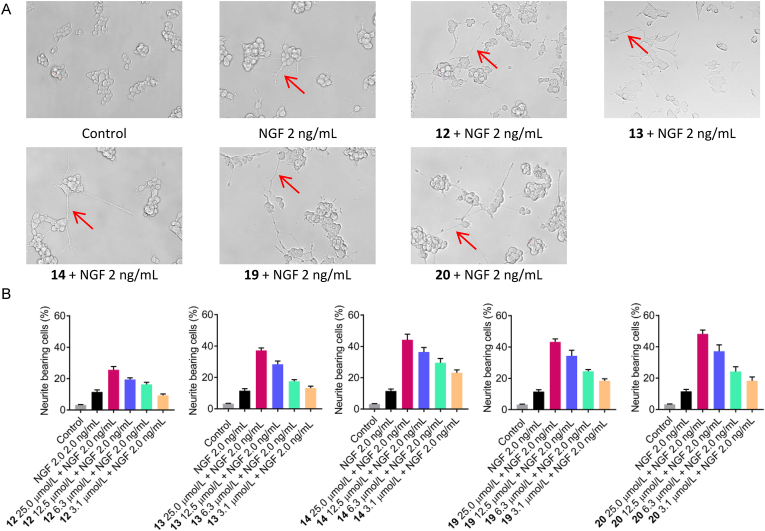

2.6. Neurite-promoting activities of new cyathane xylosides

Mushroom-derived cyathane diterpenes were demonstrated to be promising leads with potent neuroprotective and neurotrophic activities28,33,34. In the course of our work, four new cyathane xylosides (12, 13, 19, and 20) and one intermediate 14 were obtained at a level of 84.1, 100.3, 17.2, 92.5, and 98.4 mg/L, respectively. We tested their neurite-promoting activities by using PC12 cell line. The effects of compounds 12–14, 19, and 20 on the neurite outgrowth of undifferentiated PC12 cells were evaluated by morphological observations and a quantitative analysis of neurite-bearing cells. All these five compounds showed significant neurotrophic effects in the range of 6.3–25.0 μmol/L, as compared with the group that used NGF with neurite-bearing cells of 11.5 ± 1.3% at the concentration of 2.0 ng/mL (Fig. 6). The preliminary structure–activity relationship analysis shows that hydroxylation at C-11 and C-15 benefits for the neurotrophic effects, which was indicated by the higher activity of 13 and 14 than that of 12. All above evidences provided new evidence supporting the combinatorial biosynthetic strategy as an effective way to expand the chemical space of bioactive natural products.

Figure 6.

Neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells after 24 h treatment with NGF and compounds. (A), Neurites of PC-12 cells treated with NGF (2.0 ng/mL) or compounds (25 μmol/L). (B), The percentage of positive neurite-bearing cells treated with NGF and compounds. All plots show mean ± SD for n = 3 replicates.

3. Discussion

Numerous natural products with attractive bioactivities have been characterized from cultures or fruiting bodies of mushroom35, 36, 37, 38. More importantly, some of mushroom-derived bioactive compounds are being under clinical investigations. Lefamulin, a derivative of pleuromutilin (one diterpene isolated from Clitopilus passeckerianus), has been approved for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in 201939. Irofulven, an analog of illudin S (one sesquiterpene from Omphalotus olearius), exhibites activities in shrinking malignant solid tumors and drug-resistant cancers during phase I clinical trials40. As to mushroom-derived cyathane derivatives, an erinacine A-enriched mycelia extract of H. erinaceus have showed an improvement in cognitive functions in 50- to 80-year-old Japanese men and women diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment41. However, the difficulty in preparing erinacines from H. erinaceus limits further human pilot studies42.

With the advance of synthetic biology tools and methods, microbes including Escherichia coli, S. cerevisiae, Aspergillus nidulans, and A. oryzae have been developed as efficient heterologous hosts for the generation of valuable natural products from plants and mushrooms43, 44, 45. For example, artemisinic acid, a precursor of artemisinin, is produced in an engineered S. cerevisiae by expression a plant dehydrogenase and a second cytochrome, with the titer of 25 g/L46. Opioids are completely biosynthesized in yeast by expression of 23 enzymes from plants, mammals, bacteria and yeast13. Tropane alkaloids are produced in an engineered baker's yeast by expression more than 20 proteins from microbes, plants and animals across six sub-cellular locations of cytosol, mitochondrion, chloroplast, peroxisome, ER membrane and vacuole47.

Diterpens are synthesized from GGPP which is derived from the mevalonate pathway or the methylerythritol phosphate pathway. Thus, the GGPP-engineered S. cerevisiae strains including BYT20 used in this work have potential to address challenges facing in the production of bioactive diterpenes. Recently, the plant-derived miltiradiene (the precursor of tanshinone), levopimaric acid, and sclareol have been successfully synthesized in the S. cerevisiae strains engineered with high profits of GGPP and their production yields are further improved by comprehensive engineering approaches48, 49, 50, 51.

In this work, we achieved de novo biosynthesis of 22 cyathane diterpenes including erinacines A‒C, P, and T in the S. cerevisiae BYT20, and identified an unclustered EriM-coded FAD-dependent oxidase for aldehyde modification of erinacines in the genome of H. erinaceus. The formation of allyl aldehyde is critical for the structural variability in the cyathanes family and their potent anticancer activity and beneficial effects on neurons3,34. The spontaneous nonenzymatic reactions including the tandem Michael addition–elimination were demonstrated in the formation of erinacines A‒C. In addition, a new NADPH reductase EriB catalyzing the reduction of allyl aldehyde was identified and characterized. Furthermore, based on the substrate flexibility of EriJ, EriM, and EriH, we generated the GGPP-engineered S. cerevisiae producing seven “non-natural” cyathane xylosides (12, 13, 14a, 14b, 19, 20, and 22) by combinatorial biosynthetic strategy. Compounds 12, 13, 19, and 20 were attested to enhance the neurite outgrowth of undifferentiated PC12 cells in vitro. The yields of 13 known cyathane diterpenes including erinacines A, C, Q, and T and 4 “unnatural” analogues (12, 13, 19, and 20) in the GGPP-engineered S. cerevisiae reaches in the range of 13.4–112.1 mg/L (Table S2). Further studies are needed to elevate the production level of target compound. The substrate flexibility of EriB, EriJ, EriM, and EriH contributes to the structural diversity in the family of cyathanes. Discovery of eri-like gene clusters in the genome of R. mellea and B. mesenterica reveals their potential in producing cyathane derivatives.

4. Conclusions

This study gives insights into the biosynthesis of cyathanes, provides S. cerevisiae strains producing cyathanes diterpenes with good yields, and affords new cyathanes analogues including eriancines W, X, Y, ZA, ZB, and ZC. Our work also establishes an efficient platform for exploring the structural diversity in the family of cyathane-type diterpenes and elucidating the biosynthetic mechanisms of other cyathanes.

5. Experimental

5.1. Strains and growth conditions

H. erinaceus strain L547 was maintained on yeast malt medium (glucose 4.0 g/L, malt extract 10.0 g/L, yeast extract 4.0 g/L, and agar 20.0 g/L) plates at 28 °C for 7 days. S. cerevisiae BY-T20 and BJ5464-NpgA were grown on yeast extract peptone dextrose medium (YPD) plates at 30 °C. After transformation, S. cerevisiae strains were selected on synthetic dextrose complete medium (SDC) with appropriate supplements corresponding to the auxotrophic markers at 30 °C. For plasmids construction and amplification, E. coli strain DH5α was grown in liquid LB medium or solid medium (1.7% agar).

5.2. RNA extraction and cDNA preparation

The cultures of H. erinaceus in yeast malt medium were inoculated into yeast malt oat medium (glucose 4.0 g/L, malt extract 10.0 g/L, yeast extract 4.0 g/L, and oat 5.0 g/L). The fungal tissue was harvested. Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies) by using 60.0 mg of fungal sample. For degradation of genomic DNA and obtaining of cDNA, FastQuant RT Kit (TianGen Biotech) was used.

5.3. DNA fragment construction, and plasmid construction

PCR was performed using Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) or TransStart FastPfu DNA Polymerase (TransGen Biotech). The eri ORFs were amplified from cDNA of H. erinaceus L547. DNA fragments of ncpr1 ORF, promoters, terminators, and homologous recombination regions of δ site and rDNA site were amplified from the genomic DNA of S. cerevisiae BY-T20. AtUGD1 and atUXS3 ORFs were amplified from the cDNA of Arabidopsis thaliana (gifted by Prof. Bo Yu). The assembly of DNA fragments was performed by using either Double-joint PCR strategy or Clone Express® MultiS One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech)52. The primers were listed in Table S6. PCR products were confirmed by DNA sequencing. For expressing eri gene, each PCR product of eri ORFs was inserted into EcoRI/NotI-digested pESC-TRP to give the plasmids listed in Supporting Information Table S7.

5.4. Transformation of S. cerevisiae

All of the transformants used in this work are listed in Table S1. For strains SC-G and SC-GI, the DNA fragments were integrated into the δ locus of BY-T20 via homologous recombination using S.c. EasyComp Transformation Kit (Invitrogen). Similarly, the linear DNA fragments were integrated into the rDNA locus of SC-GI to afford the following strains. The plasmids pESC-TRP-EriM, pESC-TRP-EriB, pESC-TRP-EriO, pESC-TRP-EriP were used for the transformation in BY-T20 to generate the strain SC-M, SC-B, SC-O and SC-P, respectively. The plasmids pESC-TRP-EriH was used for the transformation in SC-GICAJ to generate the strain SC-GICAHJ. For protein expression, the plasmids were introduced into S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA to afford SC-Jp, SC-Hp, and SC-Pp.

5.5. HPLC analysis of extracts

Metabolites from the transformants, BY-T20, the in vitro reaction mixtures, and feeding experiments were analyzed by HPLC conducted on an Agilent 1290 HPLC System using an ODS column (C8, 250 mm × 9.4 mm, YMC Pak, 5 μm). The solvent system used was a gradient of 20%–40% acetonitrile/H2O over 8 min, 40%–76% acetonitrile/H2O over 27 min, 76%–100% acetonitrile/H2O over 5 min, and 100% acetonitrile over 15 min with 0.01% trifluoroacetate at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

5.6. Non-enzymatic transformation of 3

To determine the non-enzymatic transformation, erinacine P (3) was incubated in 100 μL buffer solution at 28 °C for 24 h. The pH value of the reaction mixture was regulated by 10 mmol/L Na2HPO4 and NaH2PO4. The mixture was analyzed by HPLC‒MS eluted by a gradient of 20%–40% acetonitrile/H2O over 8 min, 40%–76% acetonitrile/H2O over 27 min, and 76%–100% acetonitrile/H2O over 5 min with 0.05% formic acid at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The mixtures were analyzed by HPLC.

5.7. Neurotrophic activity

The neuritogenic effects of compounds 12–14, 19, and 20 were examined according to an assay using PC12 cells as reported in the early research34. Assay was performed in 24-well plate with serum-free culture medium at a density of 4 × 104 cells/well. NGF was used as positive control. The percentage of cells showing neurite outgrowth was determined by light microscopy. Cells with neurites longer than or equal to twice the length of the diameter of the cell body were scored as positive. Neurite outgrowth was assayed from at least three different regions of interest in three independent experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the National Key R&D program of China (Grant 2018YFD0400203 and 2017YEE0108200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 21472233), and the “Innovative Cross Team” project, CAS (Grant E0222L01R1, China). We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Xueli Zhang (Tianjin Institute of Industrial Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China) for the kindly providing of yeast strains BY-T20. We thank Drs. Jinwei Ren and Wenzhao Wang (Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China) for NMR and MS data collection.

Author contributions

Hongwei Liu and Ke Ma designed the research. Ke Ma and Yuting Zhang performed the experiments and analyzed the data under the guidance of Hongwei Liu, Bo Yu, and Wenbing Yin. Ke Ma and Yuting Zhang finished the sketch. Cui Guo, Yanlong Yang, Junjie Han, Bo Yu, and Wenbing Yin revised the manuscript. All authors contributed a lot to this work and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.04.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Hanson J.R. Diterpenoids of terrestrial origin. Nat Prod Rep. 2017;34:1233–1243. doi: 10.1039/c7np00040e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayer W.A., Taube H. Metabolites of Cyathus helenae. A new class of diterpenoids. Can J Chem. 1973;51:3842–3854. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang H.Y., Yin X., Zhang C.C., Jia Q., Gao J.M. Structure diversity, synthesis, and biological activity of cyathane diterpenoids in higher fungi. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:2375–2391. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150521091333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawagishi H., Shimada A., Shirai R., Okamoto K., Ojima F., Sakamoto H. Erinacines A, B and C, strong stimulators of nerve growth factor (NGF)-synthesis, from the mycelia of Hericium erinaceum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:1569–1572. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman M. Chemistry, nutrition, and health-promoting properties of Hericium erinaceus (Lion's Mane) mushroom fruiting bodies and mycelia and their bioactive compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:7108–7123. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee K.F., Chen J.H., Teng C.C., Shen C.H., Hsieh M.C., Lu C.C. Protective effects of Hericium erinaceus mycelium and its isolated erinacine A against ischemia-injury-induced neuronal cell death via the inhibition of iNOS/p38 MAPK and nitrotyrosine. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:15073–15089. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee K.F., Tung S.Y., Teng C.C., Shen C.H., Hsieh M.C., Huang C.Y. Post-treatment with erinacine A, a derived diterpenoid of H. erinaceus, attenuates neurotoxicity in MPTP model of Parkinson's disease. Antioxidants. 2020;9:137. doi: 10.3390/antiox9020137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimbo M., Kawagishi H., Yokogoshi H. Erinacine A increases catecholamine and nerve growth factor content in the central nervous system of rats. Nutr Res. 2005;25:617–623. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C.C., Cao C.Y., Kubo M., Harada K., Yan X.T., Fukuyama Y. Chemical constituents from Hericium erinaceus promote neuronal survival and potentiate neurite outgrowth via the TrkA/Erk1/2 pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1659. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enquist J.A., Jr., Stoltz B.M. Synthetic efforts toward cyathane diterpenoid natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:661–680. doi: 10.1039/b811227b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu G.J., Zhang Y.H., Tan D.X., He L., Cao B.C., He Y.P. Synthetic studies on enantioselective total synthesis of cyathane diterpenoids: cyrneines A and B, glaucopine C, and (+)-allocyathin B2. J Org Chem. 2019;84:3223–3238. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.8b03138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu G.J., Zhang Y.H., Tan D.X., Han F.S. Total synthesis of cyrneines A‒B and glaucopine C. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04480-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galanie S., Thodey K., Trenchard I.J., Interrante M.F., Smolke C.D. Complete biosynthesis of opioids in yeast. Science. 2015;349:1095–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ro D.K., Paradise E.M., Ouellet M., Fisher K.J., Newman K.L., Ndungu J.M. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature. 2006;440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W.F., Xiao H., Zhong J.J. Biosynthesis of a ganoderic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by expressing a cytochrome P450 gene from Ganoderma lucidum. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2018;115:1842–1854. doi: 10.1002/bit.26583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y.L., Zhang S., Ma K., Xu Y., Tao Q., Chen Y. Discovery and characterization of a new family of diterpene cyclases in bacteria and fungi. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;129:4827–4830. doi: 10.1002/anie.201700565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C., Minami A., Ozaki T., Wu J., Kawagishi H., Maruyama J.I. Efficient reconstitution of Basidiomycota diterpene erinacine gene cluster in Ascomycota host Aspergillus oryzae based on genomic DNA sequences. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:15519–15523. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b08935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenmoku H., Sassa T., Kato N. Isolation of erinacine P, a new parental metabolite of cyathane-xylosides, from Hericium erinaceum and its biomimetic conversion into erinacines A and B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:4389–4393. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai R., Zhang C.C., Yin X., Wei J., Gao J.M. Striatoids A‒F, cyathane diterpenoids with neurotrophic activity from cultures of the fungus Cyathus striatus. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:783–788. doi: 10.1021/np501030r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawagishi H., Shimada A., Hosokawa S., Mori H., Sakamoto H., Ishiguro Y. Erinacines E, F, and G, stimulators of nerve growth factor (NGF)-synthesis, from the mycelia of Hericium erinaceum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:7399–7402. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su P., Tong Y., Cheng Q., Hu Y., Zhang M., Yang J. Functional characterization of ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase, kaurene synthase and kaurene oxidase in the Salvia miltiorrhiza gibberellin biosynthetic pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23057. doi: 10.1038/srep23057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalb V.F., Woods C.W., Turi T.G., Dey C.R., Sutter T.R., Loper J.C. Primary structure of the P450 lanosterol demethylase gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA. 1987;6:529–537. doi: 10.1089/dna.1987.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oka T., Jigami Y. Reconstruction of de novo pathway for synthesis of UDP-glucuronic acid and UDP-xylose from intrinsic UDP-glucose in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS J. 2006;273:2645–2657. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenmoku H., Shimai T., Toyomasu T., Kato N., Sassa T. Erinacine Q, a new erinacine from Hericium erinaceum, and its biosynthetic route to erinacine C in the Basidiomycete. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66:571–575. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenmoku H., Tanaka K., Okada K., Kato N., Sassa T. Erinacol (cyatha-3,12-dien-14β-ol) and 11-O-acetylcyathin A3, new cyathane metabolites from an erinacine Q-producing Hericium erinaceum. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2004;68:1786–1789. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayer W.A., Browne L.M. Terpenoid metabolites of mushrooms and related basidiomycetes. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:2197–2248. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayer W.A., Yoshida T., van Schie D.M. Metabolites of bird's nest fungi. Part 9. diterpenoid metabolites of Cyathus africanus Brodie. Can J Chem. 1978;56:2113–2120. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y.T., Liu L., Bao L., Yang Y.L., Ma K., Liu H.W. Three new cyathane diterpenes with neurotrophic activity from the liquid cultures of Hericium erinaceus. J Antibiot. 2018;71:818–821. doi: 10.1038/s41429-018-0065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasahara K., Miyamoto T., Fujimoto T., Oguri H., Tokiwano T., Oikawa H. Solanapyrone synthase, a possible Diels‒Alderase and iterative type I polyketide synthase encoded in a biosynthetic gene cluster from Alternaria solani. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1245–1252. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambou K., Pennati A., Valsecchi I., Tada R., Sherman S., Sato H. Pathway of glycine betaine biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12:853–863. doi: 10.1128/EC.00348-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hecht H.J., Höfle G., Steglich W. Striatin A, B, and C: novel diterpenoid antibiotics from Cyathus striatus; X-ray crystal structure of striatin A. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1978;15:665–666. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y.R., Naresh A., Liang S.Y., Lin C.H., Chein R.J., Lin H.C. Discovery of a dual function cytochrome P450 that catalyzes enyne formation in cyclohexanoid terpenoid biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;59:13537–13541. doi: 10.1002/anie.202004435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi X.W., Liu L., Gao J.M., Zhang A.L. Cyathane diterpenes from Chinese mushroom Sarcodon scabrosus and their neurite outgrowth-promoting activity. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46:3112–3117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcotullio M.C., Pagiotti R., Maltese F., Mwankie G.N., Hoshino T., Obara Y. Cyathane diterpenes from Sarcodon cyrneus and evaluation of their activities of neuritegenesis and nerve growth factor production. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:2878–2882. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joynera P.M., Cichewicz R.H. Bringing natural products into the fold-exploring the therapeutic lead potential of secondary metabolites for the treatment of protein-misfolding-related neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28:26–47. doi: 10.1039/c0np00017e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schobert R., Knauer S., Seibt S., Biersack B. Anticancer active illudins: recent developments of a potent alkylating compound class. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18:790–807. doi: 10.2174/092986711794927766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaidman B.Z., Yassin M., Mahajna J., Wasser S.P. Medicinal mushroom modulators of molecular targets as cancer therapeutics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:453–468. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1787-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen H.P., Liu J.K. In: Progress in the chemistry of organic natural products 106. Kinghorn A.D., Falk H., Gibbons S., Kobayashi J., editors. Springer; Cham: 2017. Secondary metabolites from higher fungi; pp. 1–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobsson S., Paukner S., Golparian D., Jensen J.S., Unemo M. In vitro activity of the novel pleuromutilin lefamulin (BC-3781) and effect of efflux pump inactivation on multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01497-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas J.P., Arzoomanian R., Alberti D., Feierabend C., Binger K., Tutsch K.D. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic trial of irofulven. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;48:467–472. doi: 10.1007/s002800100365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mori K., Inatomi S., Ouchi K., Azumi Y., Tuchida T. Improving effects of the mushroom Yamabushitake (Hericium erinaceus) on mild cognitive impairment: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial Phytother. Res. 2009;23:367–372. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li I., Chang H.H., Lin C.H., Chen W.P., Lu T.H., Lee L.Y. Prevention of early Alzheimer's disease by erinacine A-enriched Hericium erinaceus mycelia pilot double-blind placebo-controlled study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:155. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Navale G.R., Dharne M.S., Shinde S.S. Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology for isoprenoid production in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;105:457–475. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-11040-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caesar L.K., Kelleher N.L., Keller N.P. In the fungus where it happens: history and future propelling Aspergillus nidulans as the archetype of natural products research. Fungal Genet Biol. 2020;144:103477. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2020.103477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oikawa H. Heterologous production of fungal natural products: reconstitution of biosynthetic gene clusters in model host Aspergillus oryzae. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2020;96:420–430. doi: 10.2183/pjab.96.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paddon C.J., Westfall P.J., Pitera D.J., Benjamin K., Fisher K., McPhee D. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature. 2013;496:528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srinivasan P., Smolke C.D. Biosynthesis of medicinal tropane alkaloids in yeast. Nature. 2020;585:614–619. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2650-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu T., Zhang C., Lu W. Heterologous production of levopimaric acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Factories. 2018;17:114. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-0964-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ignea C., Trikka F.A., Nikolaidis A.K., Georgantea P., Ioannou E., Loupassaki S. Efficient diterpene production in yeast by engineering Erg20p into a geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase. Metab Eng. 2015;27:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Y.J., Gao W., Rong Q.X., Jin G.J., Chu H.Y., Liu W.J. Modular pathway engineering of diterpenoid synthases and the mevalonic acid pathway for miltiradiene production. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3234–3241. doi: 10.1021/ja2114486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu T., Zhou J., Tong Y., Su P., Li X., Liu Y. Engineering chimeric diterpene synthases and isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways enables high-level production of miltiradiene in yeast. Metab Eng. 2020;60:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu J.H., Hamari Z., Han K.H., Seo J.A., Reyes-Domínguez Y., Scazzocchio C. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Boil. 2004;41:973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.