Abstract

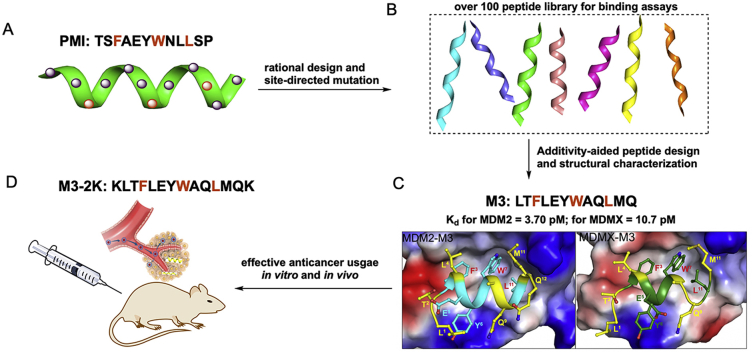

Peptide inhibition of the interactions of the tumor suppressor protein P53 with its negative regulators MDM2 and MDMX activates P53 in vitro and in vivo, representing a viable therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment. Using phage display techniques, we previously identified a potent peptide activator of P53, termed PMI (TSFAEYWNLLSP), with binding affinities for both MDM2 and MDMX in the low nanomolar concentration range. Here we report an ultrahigh affinity, dual-specificity peptide antagonist of MDM2 and MDMX obtained through systematic mutational analysis and additivity-based molecular design. Functional assays of over 100 peptide analogs of PMI using surface plasmon resonance and fluorescence polarization techniques yielded a dodecameric peptide termed PMI-M3 (LTFLEYWAQLMQ) that bound to MDM2 and MDMX with Kd values in the low picomolar concentration range as verified by isothermal titration calorimetry. Co-crystal structures of MDM2 and of MDMX in complex with PMI-M3 were solved at 1.65 and 3.0 Å resolution, respectively. Similar to PMI, PMI-M3 occupied the P53-binding pocket of MDM2/MDMX, which was dominated energetically by intermolecular interactions involving Phe3, Tyr6, Trp7, and Leu10. Notable differences in binding between PMI-M3 and PMI were observed at other positions such as Leu4 and Met11 with MDM2, and Leu1 and Met11 with MDMX, collectively contributing to a significantly enhanced binding affinity of PMI-M3 for both proteins. By adding lysine residues to both ends of PMI and PMI-M3 to improve their cellular uptake, we obtained modified peptides termed PMI-2K (KTSFAEYWNLLSPK) and M3-2K (KLTFLEYWAQLMQK). Compared with PMI-2K, M3-2K exhibited significantly improved antitumor activities in vitro and in vivo in a P53-dependent manner. This super-strong peptide inhibitor of the P53-MDM2/MDMX interactions may become, in its own right, a powerful lead compound for anticancer drug development, and can aid molecular design of other classes of P53 activators as well for anticancer therapy.

Key words: MDM2, MDMX, P53, Antitumor peptide, Systematic mutational analysis

Abbreviations: FP, fluorescence polarization; ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry; MDM2, murine double minute 2; MDMX, murine double minute X; PMI, P53‒MDM2/MDMX inhibitor; SAR, structure‒activity relationship; SPR, surface plasmon resonance

Graphical abstract

PMI-M3 was identified as the arguably most potent peptide activator of P53 reported to date, with single-digit picomolar binding affinities for both MDM2 and MDMX.

1. Introduction

Conventional genotoxic chemotherapy of human cancers not only exerts severe side effects in patients, but can also contribute to cancer recurrence due to drug-induced DNA damage and mutation1. By contrast, targeted molecular therapy is superior to chemotherapy as the former aims to kill tumor cells while sparing normal cells by targeting specific proteins or signaling pathways that either promote or suppress tumorigenesis. One of the most promising molecular targets for anticancer therapy is the tumor suppressor protein P53, a transcription factor that induces powerful growth inhibitory and apoptotic responses to cellular stress and plays a pivotal role in preventing damaged cells from becoming cancerous2, 3, 4, 5.

Dubbed the “guardian of the genome”3, P53 is functionally inactivated in almost all human cancers, where either the TP53 gene is mutated or wild type P53 protein is targeted for degradation by the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2 and/or its homolog MDMX6, 7, 8. In fact, in many tumor cells harboring wild type P53, MDM2 and/or MDMX are often elevated, conferring P53 inactivation and tumor development and progression9,10. Numerous studies have demonstrated that restoring endogenous P53 activity can halt tumor growth in vitro and in vivo11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, validating P53 activation through MDM2/MDMX antagonism, differing from conventional genotoxic chemotherapy, as a viable therapeutic paradigm for cancer treatment10,17, 18, 19, 20.

Oncogenic MDM2 and MDMX can bind via their N-terminal domain of ~110 amino acid residues to the N-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) of P53, a molecular event leading not only to MDM2/MDMX-mediated P53 degradation but also to direct inhibition of P53 transactivation activity21,22. Much of the current research focuses on the design of different classes of MDM2/MDMX antagonists to activate P53, including low molecular weight compounds17,19,23, small peptides24,25, peptidomimetics26, 27, 28, and miniature proteins29, 30, 31, 32. Successful examples currently in clinical trial include a cis-imidazoline analog termed Nutlin-3 and spiro-oxindole-derived compounds19,33,34, both of which antagonize MDM2 to inhibit tumor growth by activating the P53 pathway17,18,23.

Unlike small molecule inhibitors that are generally specific for MDM2, peptide activators of P53 are capable of antagonizing both MDM2 and MDMX at high affinities24,31,35,36. Growing evidence suggests that MDM2 and MDMX cooperatively inhibit P53 activity and cellular stability in some tumors and that dual-specificity antagonists are needed to achieve robust and sustained P53 activation for optimal therapeutic efficacy18,37.

Using phage display techniques, we previously identified a potent dodecameric peptide antagonist termed PMI (TSFAEYWNLLSP) with dual-specificity for both MDM2 and MDMX35,36; PMI binds to the P53-binding domains of MDM2 (residues 25‒109) and MDMX (residues 24‒108) at respective affinities of 3.2 and 8.5 nmol/L as determined by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) techniques. Structural studies of PMI and analogs in complex with MDM2 and MDMX pinpointed four critical hydrophobic residues for energetic contributions: Phe3, Tyr6, Trp7, and Leu1035,36.

It is important to point out, however, that phage-selected peptide ligands invariably do not constitute the optimal binding solution for target proteins because inherent variations in codon representation, library size, and expression efficiency contribute to biased selection. Not surprisingly, a single mutation, N8A, turned PMI into one of the most potent dual-specificity inhibitors of the P53‒MDM2/MDMX interactions reported to date, registering respective Kd values of 490 pmol/L and 2.4 nmol/L for MDM2 and MDMX35. Here we report systematic mutational analysis of PMI interacting with MDM2 and MDMX to further improve its binding affinity for both oncogenic proteins. A dodecameric peptide termed PMI-M3 (LTFLEYWAQLMQ) is identified to be able to bind MDM2 and MDMX with Kd values in the low picomolar concentration range. A linear peptide termed M3-2K, derived from this ultrahigh-affinity and dual-specificity peptide, effectively suppressed tumor growth in vitro and in vivo in a P53-depedent manner.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Peptide and protein synthesis

All peptides used in this work were chemically synthesized in a stepwise fashion using a machine-assisted Boc chemistry tailored from the optimized HBTU activation/DIEA in situ neutralization protocol originally developed by Kent and colleagues38. After chain assembly, the side chain protecting groups were removed and peptides cleaved from the resin by treatment with anhydrous HF and p-cresol (9:1) at 0 °C for 1 h. Crude peptides were precipitated with cold ether and purified to >98% purity by preparative C18 reversed-phase (RP) HPLC. The synthesis of MDM2 (25‒109) and MDMX (24‒108) via native chemical ligation39,40 was essentially as described previously36, and purified to >98% purity by RP-HPLC. The molecular masses of all peptides and proteins were ascertained within experimental error by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Protein and peptide solutions were quantified by UV absorbance measurements at 280 nm using molar extinction coefficients calculated from a published algorithm41.

2.2. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

Competition binding kinetics was carried out at 25 °C using a Biacore T100 SPR instrument and15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 P53-immobilized CM5 sensor chips as described29,35,36,42. 50 or 100 nmol/L MDM2 (25‒109) and MDMX (24‒108) was incubated in 10 mmol/L HEPES buffer containing 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4, with varying concentrations of peptide inhibitor before SPR analysis. The concentration of unbound MDM2 or MDMX in solution was deduced, based on P53-association RU values, from a calibration curve established by RU measurements of different concentrations of MDM2/MDMX injected alone. Three independent experiments, each in duplicate, were performed.

2.3. Fluorescence polarization (FP) based competitive binding assay

An FP-based competitive binding assay was established using MDM2 (25–109), MDMX (24‒108) and a fluorescently tagged PMI peptide. Succinimidyl ester-activated carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA-NHS) was covalently conjugated to the N-terminus of PMI (TSFAEYWNLLSP) (KdPMI–MDM2 = 3.2 nmol/L, KdPMI–MDMX = 8.5 nmol/L). Unlabeled PMI competed with TAMRA-PMI for MDM2/MDMX binding, based on which the Kd values of TAMRA-PMI with MDM2 and MDMX were determined by changes in FP to be 3.8 and 5.7 nmol/L, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. S1). As an additional positive control, we quantified the binding of Nutlin-3 to MDM2 and MDMX, yielding respective Ki values of 5.1 nmol/L and 1.54 μmol/L, similar to the values reported in the literature. For dose-dependent competitive binding experiments, MDM2 or MDMX protein (50 nmol/L) was first incubated with TAMRA-PMI peptide (10 nmol/L) in PBS (pH 7.4) on a Costar 96-well plate, to which a serially diluted solution of test peptide was added to a final volume of 125 μL. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the FP values were measured at λex = 530 nm and λem = 580 nm on a Tecan Infinite M1000 plate reader. Curve fitting was performed using GRAPHPAD PRISM software, and Ki values were calculated as described previously43,44. Three independent experiments, each in duplicate, were performed.

2.4. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

Direct protein‒peptide interactions were quantified at 25 °C in PBS, pH 7.4, using a MicroCal 2000 microcalorimeter (GE Healthcare). A typical experiment involved 20 stepwise injections of 2 μL of 100 μmol/L peptide solution into an ITC cell containing 10–20 μmol/L protein solution. For background subtraction, a reference set of injections of peptide was made in a separate experiment into the buffer alone. Data were analyzed using the Microcal Origin program, yielding the binding affinity, stoichiometry and other thermodynamic parameters. Two independent experiments were performed.

2.5. Crystallization of PMI-M3 complexes

The initial screening for crystals was done with an Art Robbinson crystallization robot in vapor diffusion sitting trials with Sparse Matrix Screens available from Hampton Crystal Screen (Hampton Research), Precipitant Wizard Screen (Emerald BioSystems), Synergy Screen (Emerald BioSystems) and ProComplex and MacroSol screen from Molecular Dimensions. All crystallization experiments were performed with MDM2‒PMI-M3 complex at 10 mg/mL and MDMX‒PMI-M3 complex at 8 mg/mL in 20 mmol/L Tris buffer, pH 7.4. Conditions that produced micro crystals were then reproduced and optimized using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method (drops of 0.5 μL of protein and 0.5 μL of precipitant solution equilibrated against 700 μL of reservoir solution). Diffraction quality crystals for MDM2‒PMI-M3 crystals were obtained from a solution containing 0.1 mol/L sodium cacodylate, pH 5.5, 25% PEG (w/v) 4000. Prior to being frozen, the crystals were transferred into a crystallization solution containing 20% (v/v) glycerol. Crystals of MDMX‒PMI-M3 were grown from 14% (v/v) 2-propanol, 70 mmol/L sodium acetate/hydrochloric acid pH 4.6, 140 mmol/L calcium chloride, 30% (v/v) glycerol and soaked in mother liquor supplemented with 20% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) and 20% glycerol prior to being frozen for data collection.

2.6. Data collection, structure solution and refinement

Diffraction data for both MDM2‒PMI-M3 and MDMX‒PMI-M3 complexes were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source (SSRL) BL12-2 beam line equipped with Pilatus 6M PAD area detector. The MDM2-PMI-M3 crystals belong to a space group P21 with the unit-cell parameters a = 26.57, b = 87.89, c = 37.58 Å and α = γ = 90°, β = 92.30°, and two MDM2‒PMI-M3 complexes present in the asymmetric unit (ASU) (Table 4). The MDMX‒PMI-M3 crystals belong to a space group P21 with the unit-cell parameters a = 45.41, b = 88.03, c = 46.30 Å and α = γ = 90°, β = 90.66°, and four MDMX‒PMI-M3 complexes present in the ASU (Table 4). The data for both complexes were processed and scaled with HKL2000 package45. Structures were solved by molecular replacement with Phaser46 from the CCP4 suite based on the coordinates extracted from the structure of PMI‒MDM2 complex (PDB code: 3EQS) and PMI‒MDMX complex (PDB code: 3EQY).

Table 4.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Data collection | MDM2‒PMI-M3 | MDMX‒PMI-M3 |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97946 | 0.97946 |

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Cell parameters | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 26.6, 87.9, 36.6 | 45.4, 88.0, 46.3 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 92.30, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.7, 90.0 |

| Complexes (a.u.) | 2 | 4 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–1.65 (1.68–1.65) | 50–3.0 (3.16–3.0) |

| # of reflections | ||

| Total | 62,832 | 5072 |

| Unique | 19,635 | 3592 |

| Rmerga (%) | 7.9 (89.7) | 15.3 (36.4) |

| I/σ | 6.2 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.8) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.8 (97.6) | 49.8 (52.4) |

| Redundancy | 2.7 (3.2) | 1.4 (1.4) |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 44–1.65 | 46–3.0 |

| Rb (%) | 17.8 | 25.8 |

| Rfreec (%) | 23.1 | 31.5 |

| # of atoms | ||

| Protein | 1364 | 2632 |

| Water | 73 | – |

| Ligand/Ion | 209 | 396 |

| Overall B value (Å)2 | ||

| Protein | 32.9 | 45.2 |

| Water | 37.8 | – |

| Ligand/Ion | 28.7 | 49.7 |

| Root mean square deviation | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.66 | 1.14 |

| Ramachandran | ||

| Favored (%) | 100 | 89.8 |

| Allowed (%) | 0 | 7.7 |

| Outliers (%) | 0 | 2.5 |

| PDB ID | 5UMM | 5UML |

Rmerge = ∑│I – <I>│∑I, where I is the observed intensity and <I> is the average intensity obtained from multiple observations of symmetry-related reflections after rejections.

R = ∑‖Fo│–│Fc‖/∑│Fo│, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Rfree = as defined by Ref. 77.

The models were refined using Refmac and the structure was completed manually using COOT. For one of the copies of MDM2‒PMI-M3 present in the ASU the electron density map showed no density for the last residue Gln12 of the PMI-M3 peptide (Supporting Information Fig. S3). The final model with the resolution of 1.65 Å was refined to R-factor of 0.18 and Rfree of 0.231. Both copies are similar with a root mean square distance of 0.374 Å (Supporting Information Table S3). MDMX‒PMI-M3 complex has four copies in the ASU with the electron density map for the last residue of the PMI-M3 peptide missing in each of the copies. The RMSD between copies ranges from 0.559 to 0.833 Å (Supporting Information Table S4). The final model with the resolution of 3.00 Å was refined to R-factor of 0.261 and Rfree of 0.315. The atomic coordinates of PMI-M3 in complex with MDM2 (PDB ID code: 5UMM) and MDMX (PDB ID code: 5UML) have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank.

2.7. Cell viability assay

U87MG and U251 cells were purchased from (Pcocell life Science & technology, China) and cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco). Cells were seeded at a density of 9 × 103 per well onto the 96-well plates. After overnight culture, cells were treated with M3-2K and PMI-2K at various concentrations, followed by the incubation of 72 h. Then 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Beyotime, 0.5 mg/mL) was added for an incubation of 4 h. The medium were removed and formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO. The absorbance at 492 nm was then measured and percent cell viability was calculated on the ratio of the A492 of sample wells versus reference wells.

2.8. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

Compounds were dissolved in PB (pH = 7.2) to concentrations ranging from 10 to 50 μmol/L. The spectra were obtained on a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter at 20 °C. The spectra were collected using a 0.1 cm path-length quartz cuvette with the following measurement parameters: wavelength, 185–255 nm; step resolution 0.1 nm; speed, 20 nm/min; accumulations, 6; bandwidth, 1 nm. The helical content of each peptide was calculated as reported previously47.

2.9. Cellular uptake of PMI-2K and M3-2K

A fluorescent FITC moiety was appended via an aminocaproic acid to the N-terminal of PMI-2K and M3-2K. U87 MG cells were seeded in four-well chambered cover-glass (6 × 104 cells per well) and allowed to grow overnight. Cells were then incubated with 50 μmol/L FITC-PMI-2K or FITC-M3-2K for 4 h. Cells were washed with Dulbeccoʹs phosphate buffered saline, fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, finally incubated by DAPI to stain the cell nucleus. Imaged using an LSM 510 Zeiss Axiovert 200M (v4.0) confocal microscope. Images were analyzed using an LSM image browser.

2.10. Western blot analysis

To examine the effects of peptides on the expression of P53, MDM2, MDMX and P21, U87 or U251 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well). Fresh medium containing different dose of peptides (0, 50 and 100 μmol/L) was added, and followed by an incubation of 24 h. The protein fraction of cell lysates was resolved by 10% SDS/PAGE before membrane transfer. Primary antibodies were from Abcam; secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were from Calbiochem.

2.11. Apoptosis analysis

Necrosis/apoptosis was evaluated by flow cytometry using the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences). Briefly, U87 cells were treated with 100 μmol/L PMI-2K and M3-2K for 72 h. Cells were then harvested, washed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in 1 × binding buffer at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. 5 μL of FITC Annexin V and 5 μL of PI were added into 100 μL of the solution (1 × 105 cells). After a 15-min incubation in the dark at room temperature, 400 μL of 1 × binding buffer was added to the tube, and cells were analyzed by FACS.

2.12. Treatment of tumor xenografts in vivo

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University. The tumor xenograft mice models were prepared using BALB/c-nu mice. We subcutaneously implanted with 106 of U87MG cells (200 μL solution in PBS) in mice right hind leg. Treatment began once tumors reached sizes of 5–10 mm in diameter. Mice were randomly divided into three treatment groups (six mice per group): PMI-2K, M3-2K and PBS. Drugs were intravenously injected into the mice at the dose of 141 μmol/kg of peptides. Treatments were performed only once. Tumor volumes were monitored and calculated using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

After 21-days treatment, three mice of each group were randomly chosen. These mice were sacrificed and tumors were removed.

2.13. H&E staining

Animals were euthanized on Day 14 following peptides treatment and their tumors were harvested. Paraffin-embedded coronal sections were taken through the areas of tumors of each animal. Microtomed sections were collected every 250 μm and only the sections showing the tumors tissues were considered. A histological section was stained with Hematoxyln and Eosin (H&E). The photographs of stained sections were taken by using an optical microscope (Nikon, Japan).

3. Results

3.1. Systematic mutational analysis of PMI

We previously performed Ala scanning (i.e., amino acid residues are each individually substituted by Ala) of PMI (TSFAEYWNLLSP) coupled with functional and structural analysis and identified the four most important residues for interactions with MDM2 and MDMX, Phe3, Tyr6, Trp7 and Leu10. Among them, Phe3/Trp7 contributed the greatest free energy of binding to MDM2/MDMX, with ΔΔG ranging from −5.5 to −6.3 kcal/mol, while Tyr6/Leu10 contributed −2.3 to −3.3 kcal/mol. The two most critical residues in P53 TAD corresponding to Phe3 and Trp7 in PMI, i.e., Phe19 and Trp23 (human P53 numbering), are fully conserved across all mammalian species. For these reasons, we left Phe3 and Trp7 unchanged in constructing a dodecameric peptide library of PMI for systematic mutational analysis. Since PMI already binds strongly to both MDM2 and MDMX at a single-digit nanomolar affinity, to facilitate accurate quantification of peptide‒protein interactions, which can be challenging in the sub-nanomolar affinity range, we introduced the L10A mutation into our library to purposely weaken peptide binding to MDM2/MDMX by ~2 orders of magnitude. In all, we substituted multiple amino acid residues at each of the remaining nine positions in PMI, resulting in a total of 94 synthetic peptides designated as PMI-n1-n2, where n1 denotes the position in PMI and n2 the sequential number of an individual peptide analog at each position (Table 1 and Supporting Information Table S1). Of note, amino acid substitutions at each position were determined based on the following criteria: (1) compatibility with parent residues at structural and chemical levels, (2) previous selection by phage display as non-consensus residues, (3) presence in wild type P53 from some other animal species, (4) high helix propensity as internal residues, and/or (5) favourable charge-dipole interaction as terminal residues.

Table 1.

Amino acid residues substituted at nine positions of PMI-L10A.

| Parent sequence | 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | S | F | A | E | Y | W | N | L | A | S | P | |

| Mutational residue | A1 | A1 | E1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1 | P1 | A1 | |||

| S2 | T2 | F2 | D2 | R2 | L2 | Q2 | L2 | E2 | ||||

| E3 | D3 | S3 | G3 | V3 | V3 | P3 | T3 | D3 | ||||

| D4 | P4 | R4 | R4 | F4 | R4 | R4 | H4 | S4 | ||||

| L5 | Y5 | L5 | L5 | H5 | M5 | M5 | K5 | M5 | ||||

| V6 | L6 | M6 | M6 | L6 | K6 | K6 | R6 | H6 | ||||

| N7 | M7 | Q7 | K7 | M7 | S7 | I7 | M7 | T7 | ||||

| M8 | Q8 | D8 | Q8 | K8 | T8 | Y8 | Q8 | K8 | ||||

| Q9 | E9 | I9 | I9 | Q9 | Q9 | I9 | R9 | |||||

| Y10 | I10 | H10 | E10 | I10 | L10 | |||||||

| I11 | W11 | S11 | I11 | E11 | Q11 | |||||||

| S12 | I12 |

For initial screening, we used a fluorescence polarization (FP)-based competitive binding assay43,44, where the test compound at different concentrations was added to wells of a pre-incubated solution of MDM2/MDMX (50 nmol/L) in complex with PMI (10 nmol/L) N-terminally conjugated to TAMRA. Displacement of the fluorescently labeled PMI from the complex by the test compound resulted in a decrease in FP. On the basis of concentration-dependent changes in FP, 22 peptide analogs out of 94 were found stronger in binding to MDM2 and MDMX than the control peptide, i.e., PMI-L10A. Their amino acid sequences are tabulated in Table 2. It is worth pointing out that none of the 23 substitutions at positions 5 and 6 fared better than their parent residues Glu5 and Tyr6, which left a total of seven positions in PMI (1, 2, 4, 8, 9, 11, and 12) amenable for enhanced MDM2/MDMX binding.

Table 2.

Amino acid sequences of 22 single-substitution analogs of PMI-L10A and their Kd values determined by SPR and Ki values determined by FP at 25 °C.

| Peptide sequence | PMI‒MDM2 |

PMI‒MDMX |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (nmol/L) | Kd ratio | Ki (nmol/L) | Ki ratio | Kd (nmol/L) | Kd ratio | Ki (nmol/L) | Ki ratio | |

| TSFAEYWNLASP | 897 ± 33 | 1.0 | 441 ± 5.0 | 1.0 | 387 ± 22 | 1.0 | 159 ± 2.0 | 1.0 |

| LSFAEYWNLASP | 123 ± 10 | 7.3 | 67.0 ± 3.0 | 6.6 | 91.0 ± 5.0 | 4.3 | 47.0 ± 1.0 | 3.4 |

| TTFAEYWNLASP | 346 ± 23 | 2.6 | 166 ± 2.0 | 2.7 | 156 ± 8.0 | 2.5 | 50.0 ± 1.0 | 3.2 |

| TSFLEYWNLASP | 98.0 ± 5.0 | 9.2 | 68.0 ± 1.0 | 6.5 | 53.0 ± 4.0 | 7.3 | 28.0 ± 1.0 | 5.7 |

| TSFAEYWALASP | 229 ± 11 | 3.9 | 99.0 ± 2.0 | 4.5 | 52.0 ± 4.0 | 7.4 | 26.0 ± 2.0 | 6.1 |

| TSFAEYWLLASP | 344 ± 8.0 | 2.6 | 124 ± 2.0 | 3.6 | 112 ± 9.0 | 3.5 | 42.0 ± 2.0 | 3.8 |

| TSFAEYWRLASP | 614 ± 33 | 1.5 | 341 ± 6.0 | 1.3 | 55.0 ± 4.0 | 7.0 | 24.0 ± 1.0 | 6.6 |

| TSFAEYWTLASP | 962 ± 29 | 0.9 | 415 ± 5.0 | 1.1 | 244 ± 16 | 1.6 | 79.0 ± 2.0 | 2.0 |

| TSFAEYWELASP | 524 ± 15 | 1.7 | 172 ± 3.0 | 2.6 | 159 ± 9.0 | 2.4 | 42.0 ± 1.0 | 3.8 |

| TSFAEYWNQASP | 535 ± 21 | 1.7 | 200 ± 3.0 | 2.2 | 416 ± 6.0 | 0.9 | 109 ± 3.0 | 1.5 |

| TSFAEYWNRASP | 716 ± 35 | 1.3 | 276 ± 6.0 | 1.6 | 394 ± 15 | 1.0 | 90.0 ± 2.0 | 1.8 |

| TSFAEYWNMASP | 692 ± 25 | 1.3 | 223 ± 3.0 | 2.0 | 164 ± 11 | 2.4 | 65.0 ± 1.0 | 2.4 |

| TSFAEYWNLATP | 493 ± 10 | 1.8 | 464 ± 7.0 | 1.0 | 321 ± 19 | 1.2 | 89.0 ± 2.0 | 1.8 |

| TSFAEYWNLAMP | 198 ± 4.0 | 4.5 | 121 ± 2.0 | 3.6 | 106 ± 3.0 | 3.7 | 48.0 ± 1.0 | 3.3 |

| TSFAEYWNLASA | 152 ± 4.0 | 5.9 | 121 ± 2.0 | 3.6 | 182 ± 7.0 | 2.1 | 63.0 ± 1.0 | 2.5 |

| TSFAEYWNLASE | 202 ± 4.0 | 4.4 | 130 ± 3.0 | 3.4 | 358 ± 7.0 | 1.1 | 132 ± 2.0 | 1.2 |

| TSFAEYWNLASS | 202 ± 5.0 | 4.4 | 107 ± 2.0 | 4.1 | 244 ± 13 | 1.6 | 120 ± 3.0 | 1.3 |

| TSFAEYWNLASM | 229 ± 4.0 | 3.9 | 77.0 ± 2.0 | 5.7 | 94.0 ± 7.0 | 4.1 | 34.0 ± 1.0 | 4.7 |

| TSFAEYWNLASH | 192 ± 12 | 4.7 | 96.0 ± 3.0 | 4.6 | 389 ± 11 | 1.0 | 162 ± 3.0 | 1.0 |

| TSFAEYWNLAST | 185 ± 5.0 | 4.8 | 79.0 ± 3.0 | 5.6 | 280 ± 11 | 1.4 | 122 ± 2.0 | 1.3 |

| TSFAEYWNLASK | 163 ± 7.0 | 5.5 | 82.0 ± 3.0 | 5.4 | 236 ± 7.0 | 1.6 | 109 ± 3.0 | 1.5 |

| TSFAEYWNLASR | 171 ± 3.0 | 5.2 | 117 ± 3.0 | 3.8 | 185 ± 9.0 | 2.1 | 63.0 ± 2.0 | 2.5 |

| TSFAEYWNLASQ | 132 ± 2.0 | 6.8 | 78.0 ± 2.0 | 5.7 | 134 ± 7.0 | 2.9 | 58.0 ± 1.0 | 2.7 |

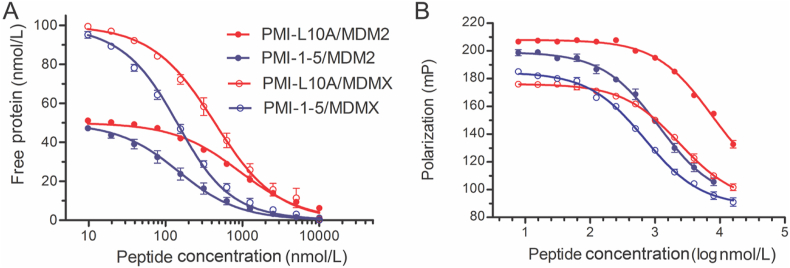

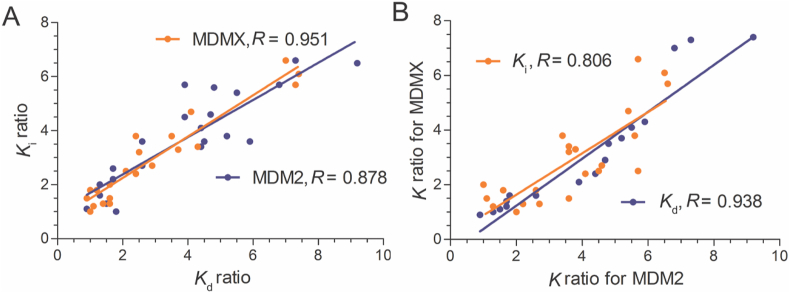

Next, we measured the binding affinities of the 22 peptide analogs and PMI-L10A for MDM2 and MDMX using two independent techniques (Fig. 1), surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and FP as previously reported36,42, 43, 44. As shown in Table 2, individual mutations at positions 1, 2, 4, 8, 9, 11, and 12 enhanced PMI-L10A binding to MDM2/MDMX by as much as one order of magnitude. The Kd values determined by SPR are largely consistent with the Ki values determined by FP. In fact, the Pearson correlation plot of Ki ratios of the 22 peptide analogs relative to PMI-L10A versus corresponding Kd ratios gave rise to correlation coefficients of 0.878 and 0.951 for MDM2 and MDMX, respectively (Fig. 2A). Further, Ki or Kd ratios for MDM2 were also highly correlated to those for MDMX (Fig. 2B), suggesting that mutations good for MDM2 generally improve peptide binding to MDMX as well. For example, the T1L mutation augmented peptide binding to MDM2 by 7.3-fold (Kd) and 6.6-fold (Ki), and to MDMX by 4.3-fold (Kd) and 3.4-fold (Ki); the A4L mutation enhanced peptide binding to MDM2 by 9.2-fold (Kd) and 6.5-fold (Ki), and to MDMX by 7.3-fold (Kd) and 5.7-fold (Ki). Although most mutations improved peptide binding to MDM2 more than to MDMX, several mutations clearly showed strong energetic preference for MDMX over MDM2, including N8R and the N8A mutation previously identified by an Ala scan of PMI. Taken together, the systematic mutational analysis allowed us to identify the most potent residue at each of the seven positions in PMI for MDM2/MDMX binding (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Quantification of the interactions of MDM2 (25–109) and MDMX (24–108) with representative PMI analogs by SPR- (A) and FP-based (B) competition assays. (A) MDM2 (dot) at 50 nmol/L or MDMX (circle) at 100 nmol/L was incubated at 25 °C, pH 7.4, with varying concentrations of PMI-L10A (red) or PMI-1-5 (blue), and the concentrations of unbound protein were quantified by SPR on a P53 TAD peptide-immobilized CM5 sensor chip. (B) MDM2 (dot) or MDMX (circle) at 50 nmol/L pre-complexed with 10 nmol/L of a TAMRA-labeled PMI peptide was incubated at 25 °C, pH 7.4, with varying concentrations of PMI-L10A (red) or PMI-1-5 (blue), and the displacement of TAMRA-PMI by PMI analog led to a progressive decrease in fluorescence polarization. Kd and Ki values were obtained through a non-linear regression analysis as previously described, and each curve is the mean of three independent measurements.

Figure 2.

Pearson correlation analysis of MDM2 and MDMX interactions with PMI analogs. (A) Plot of Ki ratios of 22 peptide analogs relative to PMI-L10A versus corresponding Kd ratios, yielding correlation coefficients R of 0.878 and 0.951 for MDM2 (blue) and MDMX (orange), respectively. (B) Plot of relative Ki or Kd ratios for MDMX versus those for MDM2, yielding respective correlation coefficients R of 0.806 for Ki (orange) and 0.938 for Kd (blue).

3.2. Additivity-aided molecular design

If the free energy change caused by multiple substitutions of amino acid residues in a peptide is equal to the sum of the free energy changes contributed by each single substitution, then the system is said to be additive48,49. An additive system can be expressed mathematically by Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where ΔΔG represents the free energy change relative to wild type; ni stands for position i where single mutation occurs; (n1, …, ni, …, nj) stands for positions 1 to j where multiple mutations occur. In an additive interacting system, the most potent peptide antagonist of MDM2 or MDMX can be readily constructed by combining the best mutations at individual positions into one sequence. For example, the amino acid sequence of a potent peptide antagonist of MDM2 could be created by introducing 7 mutations (best for MDM2) into PMI-L10A, i.e., T1L, S2T, A4L, N8A, L9Q, S11M and P12Q, yielding LTFLEYWAQAMQ termed PMI-M2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Amino acid sequences of multi-substitution analogs of PMI-L10A and their Kd values determined by SPR or ITC and Ki values determined by FP at 25 °C.

| Peptide sequence | PMI‒MDM2 |

PMI‒MDMX |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd or Ki (nmol/L) | Ratio | Kd or Ki (nmol/L) | Ratio | ||

| PMI | TSFAEYWNLLSP | Kd = 2.70 ± 0.50 | 332 | Kd = 8.20 ± 1.4 | 47 |

| Ki = 3.00 ± 2.3 | 147 | Ki = 4.90 ± 2.0 | 32 | ||

| PMI-L10A | TSFAEYWNLASP | Kd = 897 ± 33 | 1.0 | Kd = 387 ± 22 | 1.0 |

| Ki = 441 ± 5.0 | 1.0 | Ki = 159 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | ||

| PMI-M2 | LTFLEYWAQAMQ | Kd = 1.60 ± 0.80 | 560 | Kd = 2.30 ± 0.60 | 168 |

| Ki = 3.60 ± 1.4 | 123 | Ki = 1.90 ± 1.1 | 84 | ||

| PMI-M3 | LTFLEYWAQLMQ | Kd = 3.70 ± 0.4 pmol/La | Kd = 10.7 ± 2.4 pmol/La | ||

| PMI-M4 | LTFLEYWNLASP | Kd = 31.6 ± 2.3 | 28 | Kd = 13.0 ± 2.0 | 30 |

| Ki = 20.0 ± 1.4 | 22 | Ki = 5.80 ± 1.2 | 27 | ||

| PMI-M5 | TSFAEYWAQAMQ | Kd = 15.9 ± 1.7 | 56 | Kd = 13.0 ± 2.2 | 30 |

| Ki = 9.00 ± 1.6 | 49 | Ki = 8.60 ± 1.4 | 18 | ||

Kd values determined by ITC.

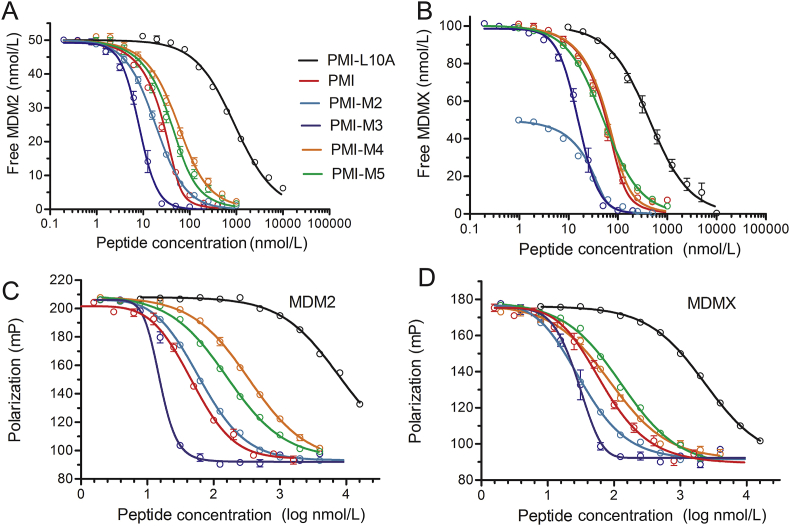

SPR- and FP-based affinity quantification (Fig. 3) showed that the 7 mutations collectively enhanced peptide binding to MDM2 and MDMX by 560-fold (Kd) or 123-fold (Ki) and 168-fold (Kd) or 84-fold (Ki), respectively. Assuming a perfect additivity, however, PMI-M2 would bind to MDM2 35,000-fold (Kd) or 23,000-fold (Ki) stronger than PMI-L10A, and to MDMX at an enhanced affinity by 5600-fold (Kd) or 5000-fold (Ki) as calculated from the values in Table 2. The deviation of ΔΔG (n1, …, ni, …, nj) from ∑ΔΔG (ni) amounted to RTln(35000/560) = 2.4 kcal/mol (R = 1.987 cal/(K·mol), T = 298.2 K) for MDM2 and RTln(5600/168) = 2.1 kcal/mol for MDMX (based on Kd measurements). Clearly, PMI was a severely non-additive system with respect to MDM2/MDMX binding and posed a challenge to the design of ultrahigh-affinity and dual-specific peptide antagonists of both MDM2 and MDMX.

Figure 3.

Quantification of the interactions of MDM2 and MDMX with PMI and representative analogs by SPR- and FP-based competition assays. (A) MDM2 at 50 nmol/L with PMI, PMI-L10A, PMI-M2, PMI-M3, PMI-M4, and PMI-M5, and (B) MDMX at 50 or 100 nmol/L with various PMI peptides as quantified by SPR. (C) MDM2, and (D) MDMX at 50 nmol/L with various PMI peptides as quantified by FP. The experimental details were essentially as described in the legend of Fig. 1 and Section 2. Each curve is the mean of three independent measurements.

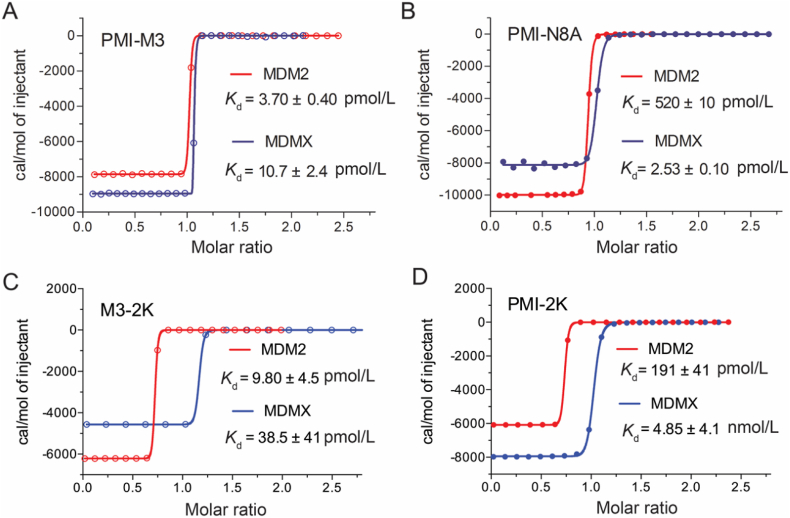

PMI-M2 bound to MDM2/MDMX at low single-digit nanomolar affinities, several-fold stronger for MDMX than the parent peptide PMI (Table 3). However, the reversion of Ala10 in PMI-M2 to Leu (yielding PMI-M3) dramatically improved, as expected, peptide binding to MDM2 and MDMX to the extent that reliable Kd or Ki values could no longer be determined by the SPR and FP techniques (Fig. 3 and Table 3). We resorted to isothermal titration calorimetry techniques to quantify the ultrahigh affinity interaction between PMI-M3 and MDM2/MDMX (Fig. 4 and Supporting Information Fig. S2). PMI-M3 bound to MDM2 and MDMX with respective Kd values of 3.7 and 10.7 pmol/L, thereby representing the most potent dual-specificity peptide antagonist of MDM2 and MDMX reported to date. Since the L10A mutation lowered the respective binding affinity (Kd) of PMI for MDM2 and MDMX by 332- and 47-fold (Table 3), the predicted Kd values of PMI-M3 for MDM2 and MDMX would be 4.8 pmol/L (1.6 nmol/L divided by 332) and 49 pmol/L (2.3 nmol/L divided by 47), respectively. These predicted Kd values are rather close to the experimentally determined Kd values, suggesting that the additivity rule largely holds true for the single mutation L10A. Nevertheless, dual-specificity peptide ligands of MDM2/MDMX that are more potent than PMI-M3 likely exist due to the non-additive nature of the 7 mutations introduced into PMI-L10. Further, a different combination of 7 mutations could conceivably result in potent peptide antagonists more specific for MDMX than for MDM2. It is worth pointing out that exceedingly tight bindings are always difficult to quantify biophysically with high accuracy and certainty, and our ITC experiments were no exception. We performed multiple ITC runs with similar Kd values but different degrees of standard deviation, and only the data from one representative run with a low SD were presented in Fig. 4 and Fig. S2).

Figure 4.

Interactions of PMI-M3, PMI-N8A, M3-2K and PMI-2K with MDM2 and MDMX as quantified at 25 °C by isothermal titration calorimetry. The respective Kd values of PMI-N8A for MDM2 and MDMX measured by ITC in this work are in good agreement with the Kd values of 490 pmol/L and 2.4 nmol/L previously determined by SPR.

3.3. Sources of non-additivity

Non-additivity is known to arise from factors such as peptide conformational flexibility and interacting side chains48,49, contributing to a significant deviation of ΔΔG (n1, …, ni, …, nj) from ∑ΔΔG (ni). To explore the sources of non-additivity of PMI, we divided the 7 mutations into two groups, T1L, S2T and A4L in the N-terminal region and N8A, L9Q, S11M and P12Q in the C-terminal region, and characterized two resultant peptide analogs of PMI-L10A, i.e., T1L/S2T/A4L-PMI-L10A (or PMI-M4) and N8A/L9Q/S11M/P12Q-PMI-L10A (or PMI-M5) (Fig. 3, Table 3). PMI-M4 bound to MDM2 at an affinity of 31.6 nmol/L, or 28 fold stronger than PMI-L10A, in comparison to its expected 175 fold increase in binding (Table 2); PMI-M4 bound to MDMX at affinity of 13.0 nmol/L, or 30 fold stronger than PMI-L10A, when it was predicted to be 78-fold more potent (Table 2). The free energy changes associated with non-additivity were therefore RTln(175/28) = 1.1 kcal/mol for MDM2 and RTln(78/30) = 0.56 kcal/mol for MDMX (R = 1.987 cal/(K·mol), T = 298.2 K); similar calculations for PMI-M5 yielded 0.76 kcal/mol and 0.51 kcal/mol for MDM2 and MDMX, respectively. These results suggest that the three N-terminal mutations T1L/S2T/A4L contributed more to non-additivity of PMI-L10A than the four C-terminal mutations N8A/L9Q/S11M/P12Q. It is worth pointing out that seven different combinations of two or three mutations in the C-terminal region all displayed non-additive effects on peptide binding to MDM2/MDMX (Supporting Information Table S2). However, none of the seven peptides showed stronger binding than their parent peptide containing all four C-terminal mutations, N8A/L9Q/S11M/P12Q (Table S2), partially validating the design of PMI-M3.

3.4. Structural validation

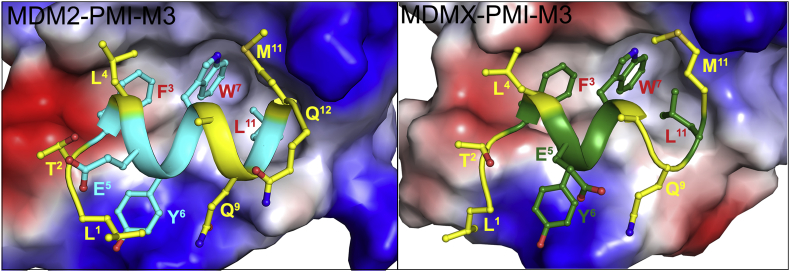

To better understand molecular basis of high-affinity interaction of PMI-M3 with MDM2/MDMX we obtained its co-crystal structure with MDM2 and MDMX at 1.65 and 3.0 Å resolution, respectively (Fig. 5, Table 4). In both complexes the PMI-M3 peptide binds within the P53-binding site of MDM2/MDMX by placing the side chains of Phe3, Trp7 and Leu11 into complementary hydrophobic sub-pockets (Fig. 5). However, while all 12 residues of PMI-M3 contribute to MDM2 binding, 11 of them are engaged in interactions with MDMX. Missing in the crystallographic electron density map is Gln12 of PMI-M3 in each of four copies of the MDMX‒PMI-M3 complex in the asymmetric unit, indicating that the C-terminal residue is disordered and does not directly contribute to MDMX binding.

Figure 5.

Crystal structure of MDM2 and MDMX in complex with PMI-M3. The electrostatic potential is displayed over the molecular surfaces of MDM2/MDMX colored red for negative, blue for positive and white for apolar. The PMI-M3 peptide is shown in a ribbon and stick representation. Residues mutated in PMI-M3 (as compared to PMI sequence) are shown in yellow. 12 and 11 residues of PMI-M3 are resolved in the MDM2‒PMI-M3 and MDMX‒PMI-M3 crystal structures, respectively.

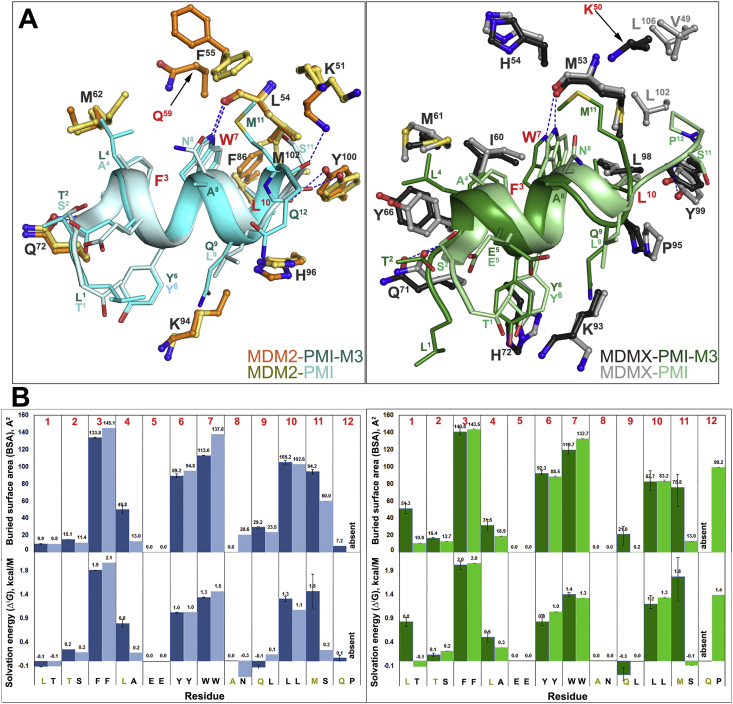

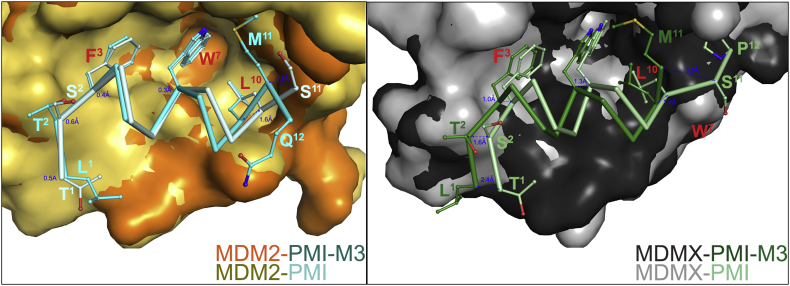

Structural alignment of the MDM2‒ and MDMX‒PMI-M3 complexes to the respective complexes formed between MDM2/MDMX and PMI reveals both close similarities and noticeable differences in binding mode between PMI-M3 and PMI (Fig. 6, Tables S3 and S4). PMI-M3 and PMI peptides largely overlap when bound to the P53 cavity of MDM2 with the distances between equivalent Cα atoms of the peptide backbone of the seven N-terminal residues not exceeding 0.6 Å (Fig. 7). However, this is not the case in the C-terminal region where their modes of binding diverge. The Cα‒Cα distance propagates progressively starting from Trp7 and reaches a maximum of 1.6 Å at residue 11 (Met11 in PMI-M3 versus Ser11 in PMI). Overall, PMI-M3 buries 1195 Å2 at the complex interface as compared with a buried surface area (BSA) of 1140 Å2 of PMI in the MDM2‒PMI complex (Fig. 6B). The marginally increased BSA is contributed mainly by Met11 of PMI-M3, which, alone, buries 94.2 Å2 at the interface and contributes solvation energy of −1.5 kcal/mol (as opposed to 60 Å2 and ‒0.2 kcal/mol by Ser11 of PMI). Met11 of PMI-M3 also establishes a new H-bond to Lys51 of MDM2 to replace the less favorable water-mediated H-bond formed by Ser11 of PMI (Fig. 6A). In addition, two more H-bonds are formed at the MDM2‒PMI-M3 interface, which are absent at the MDM2‒PMI interface, including a water-mediated H-bond between Gln9 Oε1 of peptide and His96 Nε3 and Val93 O of MDM2 and an elongated but direct H-bond (3.7 Å) involving Tyr6 OH of PMI-M3 and Lys54 Nε1 of MDM2 (Supporting Information Fig. S4). The new H-bonding pattern along with an increased BSA seen with PMI-M3 may provide a structural explanation for its higher binding affinity for MDM2.

Figure 6.

PMI-M3 versus PMI binding to MDM2 and MDMX. (A) The MDM2‒PMI-M3/PMI and MDMX‒PMI-M3/PMI complex interfaces. The MDM2‒PMI-M3, MDM2‒PMI (PDB code: 3EQS), MDMX‒PMI-M3 and MDMX‒PMI (PDB code: 3EQY) complex structures were superimposed based on MDM2 (left) and MDMX (right). The PMI-M3 and PMI peptides are shown as ribbon-ball-stick representations. For clarity only side chains of some residues of MDM2 and MDMX are shown as ball-sticks. The same set of residues with the exception of Met102 that lines the PMI binding pocket within the MDM2 molecule is involved in PMI-M3 peptide binding (residues 51, 54–55, 57–58, 61–62, 67, 72–73, 75, 86, 91, 83–94, 96, 99–100 of MDM2). In addition, PMI-M3 makes one new contact to Gln59 of MDM2, which is mediated through the aliphatic side chain of Met11 of the PMI-M3 peptide. There are also four direct protein‒peptide H-bonds formed at the MDM2‒PMI-M3 contact interface (Q72 Oε1 to F3 N, L54 O to W3 Nε1, Y100 (OH) to L10 O and K51 Nε1 to M11 O) as compared to three formed at the MDM2‒PMI interface (Q72 Oε1 to F3 N, L54 O to W3 Nε1, Y100 (OH) to L10 O). Residues 49–50, 53–54, 56–58, 60–61, 66, 69–74, 90, 92–93, 95, 98–99 of MDMX line the PMI-M3 binding pocket. The PMI-M3 binding doesn't involve V49, L102 and L106 of MDMX, which are engaged in PMI binding. A new contact to Lys50 of MDMX is formed to accommodate Met11 of PMI-M3. There are also two direct protein‒peptide H-bonds formed at the MDMX‒PMI-M3 contact interface (Q71 Oε1 to F3 N, M53 O to W3 Nε1) as compared to three formed at the MDMX‒PMI interface (Q71 Oε1 to F3 N, M53 O to W3 Nε1 and Y99 (OH) to S11 O). (B) Analysis of the peptide-binding interface. The relative contribution of each residue of PMI-M3 (dark blue/green) and PMI (light blue/green) to MDM2/MDMX interface is shown as the buried surface area (BSA, top panel) and the solvation energy in kcal/mol (ΔiG, bottom panel) of each position as calculated by PISA. BSA represents the solvent-accessible surface area of the corresponding residue that is buried upon interface formation and the solvation energy gain of the interface is calculated as the difference in solvation energy of a residue between the dissociated and associated structures. A positive solvation energy corresponds to a negative contribution to the solvation energy gain of the interface or the hydrophobic effect. Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are not included in ΔiG. When more than one copy of the peptide is present in the asymmetric unit, values are shown as the mean with the range displayed as an error bar. The sequence for each position is shown on the bottom.

Figure 7.

Relative positioning of PMI-M3 and PMI peptides within the MDM2 and MDMX binding pockets. The complex structures were superimposed based on MDM2 (left) and MDMX (right). Only the backbones of the PMI-M3 and PMI peptides are shown with side chains as ball-stick representations for interacting residues. Molecular surfaces are displayed for the MDM2/MDMX molecules. The distances between main chain atoms of corresponding N-, C-terminal residues, Phe3, Trp7 and Leu10 of PMI-M3 and PMI were measured and shown in blue.

Notable differences are observed for PMI-M3 in the P53-binding pocket of MDMX as compared with PMI. The entire PMI-M3 backbone is shifted in relation to PMI with distances of 1.0–1.3, 2.4 and 5 Å between equivalent main-chain atoms of the Phe3-Trp7-Leu10 triads, the N-termini and C-termini, respectively (Figure 6, Figure 7). Leu1 in PMI-M3 shifts forward in the binding pocket to maximize hydrophobic contacts to MDMX (54.3 Å2 of BSA and −0.8 kcal/mol of ΔiG (Fig. 6B), as compared with Thr1 in PMI (10.9 Å2 of BSA and 0.1 kcal/mol of ΔiG). This shift propagates down the peptide, altering the binding of Phe3 and Trp7 to their respective hydrophobic sub-pockets. Met11 of the peptide compensates for the shift in Trp7 by occupying part of the Trp7 sub-pocket and contributing 75.8 Å2 of BSA and ΔiG of −1.8 kcal/mol to the interface (compared with 13 Å2 of BSA and 0.1 kcal/mol of ΔiG of equivalent Ser11 of PMI). The added BSA and solvation energy by Leu1 and Met11 in the PMI-M3 peptide may adequately compensate for the backbone shift and the loss of solvation energy contributed by Pro12 in PMI. Overall, the BSA of 1185 Å2 for MDMX‒PMI-M3 is 90 Å2 larger than that of PMI‒MDMX (1095 Å2) and increased solvation energies of Leu1 and Met11 provide a structural basis for PMI-M3's higher affinity for MDMX than PMI (Fig. 6B).

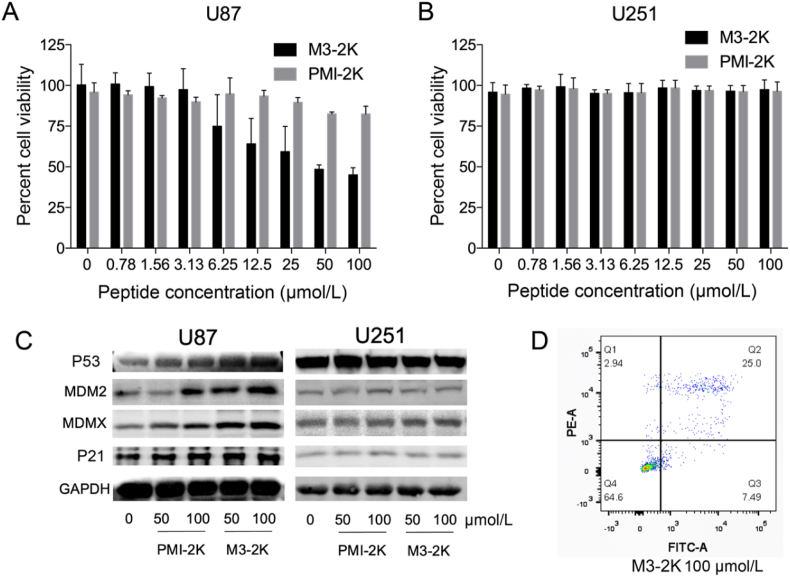

3.5. Anti-tumor activities of M3-2K in vitro

We analyzed the anti-tumor activities of peptide PMI-M3 against U87MG and U251 cancer cells by MTT assays. Not surprisingly, no anti-proliferative activity was observed against both cell lines at concentrations of up to 100 μmol/L due likely to susceptibility to proteolytic degradation and poor membrane permeability of PMI-M3. An exceedingly low water solubility of the peptide may have also limited its potential biological activities. Previous studies suggested that positive net charge would aid the peptide to permeabilize the cell membrane50. Accordingly, we added one lysine residue to both ends of peptide PMI-M3, yielding a modified linear peptide termed M3-2K. Such modification not only improved peptide solubility but also enhanced its cellular uptake (Supporting Information Fig. S5). As a control, PMI was also N- and C-terminally extended by two Lys residues, resulting in PMI-2K. Of note, Lys extension of PMI and PMI-3 had only modest effects on peptide binding affinities for MDM2 and MDMX (Fig. 4), and neither PMI-2K nor M3-2K had any effect on the viability of monkey kidney cell line Vero E6 (Supporting Information Fig. S6).

We next assessed the effectiveness of M3-2K and PMI-2K in inhibiting tumor cell growth in vitro. As shown in Fig. 8A and B, M3-2K displayed moderately strong growth inhibitory activity against U87MG, but not U251 (P53‒ mutant) cells, while PMI-2K failed to kill either cell type at up to 100 μmol/L. To further investigate the mechanisms of action of M3-2K, we analyzed the expression of P53, P21, MDMX and MDM2 in U87MG and U251 cells by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 8C, 24 h after treatment with 50 μmol/L M3-2K, a high-level induction of P53, MDM2, MDMX and P21 became evident in U87MG cells, but not in U251 cells, compared with PMI-2K and PBS treatment groups. These findings supported that intracellular M3-2K inhibited the growth of U87MG by activating the P53 pathway. Consistent with this result, an induction of apoptosis of U87MG cells by M3-2K was verified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), contrasting PMI-2K and PBS treatment groups (Fig. 8D and Supporting Information Fig. S7).

Figure 8.

M3-2K peptide kills cancer cells through activating P53 pathways in vitro. (A, B) Dose-dependent anti-proliferative activity of PMI-2K and M3-2K against U87MG and U251 cell lines. Each curve is the mean of five independent measurements. (C) U87 and U251 cells were treated with PMI-2K and M3-2K for 24 h, and Western blot was performed to analyze the expressions of P53, MDM2, MDMX and P21 proteins. GAPDH was used as loading control. (D) Apoptosis levels of M3-2K on U87 cells were determined by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometric analysis.

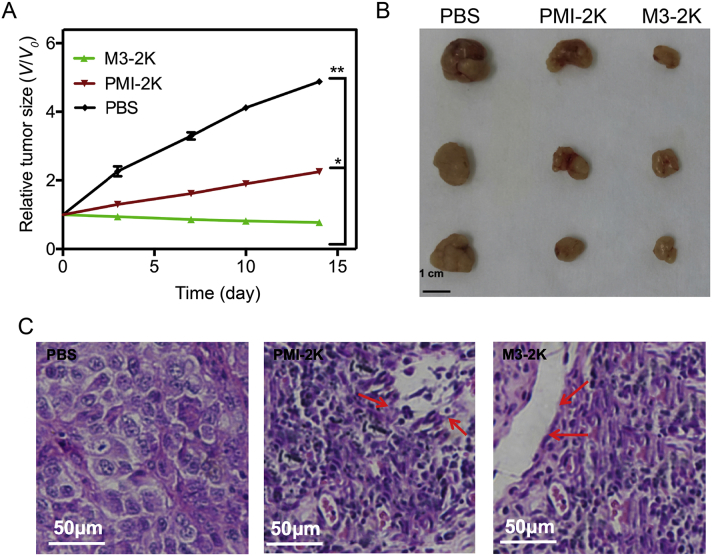

3.6. Anti-tumor activities of M3-2K in vivo

The in vivo effect of peptides on tumor growth was subsequently tested in mice bearing U87MG cell xenografts. After subcutaneous tumor xenografts had been established, M3-2K and PMI-2K linear peptides were administered at a single dose of 141 μmol/L/kg through mouse tail vein, respectively, and growth inhibition was measured one day post administration for two weeks (Fig. 9A). While PMI-2K had a moderate in vivo activity as measured by the size of tumor and rate of growth in PMI-2K and PBS treatment groups, M3-2K completely suppressed tumor growth in the animal model (Fig. 9A and B). To further characterize the in vivo anticancer activity of M3-2K at the histopathological level, we analyzed tumor tissues using H&E staining technique. As expected, compared with PMI-2K and PBS groups, M3-2K treatment significantly increased levels of apoptosis (Fig. 9C). Of note, although M3-2K and PMI-2K differ significantly in binding affinity for MDM2/MDMX, their difference in therapeutic efficacy is substantially less pronounced, implying a poor correlation between Kd values and in vivo activity. This poor correlation may arise from peptide sequence-dependent multiple unknown factors such as in vivo stability and bioavailability, membrane permeability, uptake and release efficiency, intracellular compartmental distribution, etc. Obviously, more studies are warranted to further improve therapeutic potential of these antitumor peptides.

Figure 9.

M3-2K peptide achieves effective tumor suppression in vivo. (A) Investigation of tumor volumes for each group (n = 5, ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01). (B) After the mice were sacrificed on Day 21, all tumors were isolated and their morphology were investigated. Scale bar: 0.5 cm. (C) Representative tumor sections after the 21-day treatment staining by H&E.

3.7. PDB ID codes

The atomic coordinates of PMI-M3 in complex with MDM2 (PDB ID code: 5UMM) and MDMX (PDB ID code: 5UML) have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank.

4. Discussion

Peptide antagonists of MDM2 and MDMX are superior in many aspects as P53 activators for anticancer therapeutic development, including, but not limited to, high affinity, strong specificity and low toxicity25. A number of peptide activators of P53 have been designed with potent in vitro and in vivo activity against tumors bearing wild-type P53 and elevated levels of MDM2 and/or MDMX, promising a new class of anticancer agents with therapeutic potential25. Lane and colleagues recently created a hydrocarbon-stapled derivative of N8A-PMI with exceedingly strong and persistent P53-activating activity in vitro, surpassing Nutlin-3 in potency but with significantly less toxicity51. We have recently shown that hydrocarbon-stapled PMI-N8A, when delivered via cyclic RGD-linked polymeric micelles, effectively inhibits glioblastoma growth in vivo and dramatically reduces the dose of temozolomide the standard chemo drug for glioblastoma in a combination therapy52. To further improve the therapeutic efficacy of peptide activators of P53, we aim in this work to design ultrahigh-affinity and dual-specificity peptide antagonists of MDM2 and MDMX for robust and sustained P53 activation.

Through systematic mutational analysis coupled with additivity-based rational approaches, we designed an exceedingly potent dodecameric peptide activator of P53 with dual-specificity for both MDM2 and MDMX, i.e., LTFLEYWAQLMQ or PMI-M3. PMI-M3 binds to MDM2 and MDMX at single-digit picomolar affinities as quantified by ITC, approximately three orders of magnitude stronger than its parent peptide PMI (TSFAEYWNLLSP) previously selected from phage-displayed peptide libraries35,36. In fact, PMI-M3 binding to MDM2 and MDMX was so tight that it became impossible to accurately quantify Kd values using SPR- and FP-based competition assays.

PMI and PMI-M3 substantially differ in amino acid sequence, with ~40% sequence identity (5 residues out of 12). Among the five identical residues, Phe3, Tyr6, Trp7 and Leu10 are known to be most critical energetically, contributing −5.46, −3.06, −6.31, and −3.28 kcal/mol, respectively, to PMI‒MDM2 interactions, and −5.57, −2.55, −5.94, and −2.28 kcal/mol, respectively, to PMI‒MDMX interactions35. Since the respective total free energy changes associated with PMI binding to MDM2 and MDMX were merely −11.6 and −11.0 kcal/mol35, multiple substitutions of these critical hydrophobic residues in PMI would necessarily result in huge non-additive effects. This is understandable because the side-chains of these residues are in close proximity and their subsite binding pockets on MDM2/MDMX are structurally contiguous, making it difficult to avoid compensatory side-chain movements upon amino acid substitution36. Interacting side-chains of PMI and contiguous binding pockets of MDM2/MDMX thus likely explain why significant non-additive effects were observed in our work, which was largely confirmed by the structural studies. Of note, non-additivity obviously impairs the predicting power afforded by single mutational structure‒activity relationship (SAR) analyses, constituting an impediment to rational design of multiply substituted peptide antagonists of MDM2 and MDMX. In a perfectly additive system, PMI-M3 would be seven orders of magnitude stronger than PMI for MDM2 and five orders of magnitude more potent than PMI for MDMX.

Interestingly, comparative structural studies of PMI-M3 and PMI in complex of MDM2 and MDMX did not reveal dominant subsite interactions that dramatically enhanced the binding affinity of PMI-M3 over PMI. This is consistent with the functional findings that none of the seven substitutions in PMI-M3, i.e., T1L, S2T, A4L, N8A, L9Q, S11M and P12Q, improved peptide binding to MDM2/MDMX by more than a factor of 10. Moderate increases in BSA and altered H-bonding patterns appear to be sufficient, collectively, to attain a single-digit picomolar binding affinity with PMI-M3 for both oncogenic proteins. It is plausible that its enhanced binding affinity could also be attributable to improved helix propensity as well as favorable helix dipole–charge interactions. In fact, CD spectroscopic analysis of PMI and PMI-M3 in the presence and absence of 30% TFE showed that PMI-M3 is more helical than PMI (Supporting Information Fig. S8), suggesting a smaller entropy loss associated with PMI-M3 binding to MDM2/MDMX, thus an enhanced binding affinity.

Of note, most substitutions for Pro12 at the C-terminus of PMI (9 out of 12) improved peptide binding to MDM2 and, to a lesser extent, MDMX; for the nine permissible substitutions listed in Table 2, the improvement was 5-fold on average for MDM2 but significantly smaller for MDMX except for Met12. This difference between MDM2 and MDMX is consistent with the structural findings that the side-chain of Gln12 of PMI-M3 is disordered in the complex with MDMX, thus making no energetic contribution to MDMX binding. Since the improvement in peptide binding to MDM2 was largely insensitive to the physicochemical nature of the nine residues in place of Pro12, the peptide backbone structure of an amino acid residue versus an imino acid residue at the C-terminus likely played an important role in enhanced MDM2 binding. In fact, Pro12 makes no direct contact with the protein in the PMI‒MDM2 complex structure, due to its restricted backbone conformation and resultant clashes with a protruding Tyr100 residue of MDM235,36.

Despite obvious advantages of peptide activators of P53 as a viable class of anticancer therapeutics, major pharmacological obstacles still remain in drug development. Notable weaknesses of peptide therapeutics include susceptibility to proteolytic degradation and poor membrane permeability25,53,54. Toward this end, a number of enabling technologies are available to improve drug-like properties of peptides, including but not limited to side-chain stapling50,55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, D-enantiomerization44,70, 71, 72, 73, nanoparticle-based delivery tools52,72,74, 75, 76, and protein grafting29, 30, 31, 32. In our case, by introducing two lysine residues at both ends of PMI-M3, we obtained the linear peptide M3-2K with significantly enhanced anticancer activities in vitro and in vivo. Our positive functional results on M3-2K likely arose from a combination of its improved membrane permeability and binding affinity for MDM2/MDMX, showcasing the potential of M3-2K peptide as a potent P53 activator for anticancer therapy. Due to reduced bioavailability expected of peptide therapeutics in general, the importance of functional improvement as demonstrated in this report cannot be overstated for peptide drug design and development.

5. Conclusions

We have obtained PMI-M3, the arguably most potent peptide activator of P53 reported to date, with single-digit picomolar binding affinities for both MDM2 and MDMX. PMI-M3, substantially differing in amino acid sequence from its phage-selected parent peptide PMI, is three orders of magnitude more potent in binding. Structural studies suggest that systematic mutational analysis prevails over structure-based rational design in this particular case as the latter would not have necessarily informed the sequence of PMI-M3 based on known structures of peptide‒MDM2/MDMX complexes. Importantly, the modified peptide M3-2K is capable of killing cancer cells in vitro and exerts effective tumor suppression in vivo through activating the P53 pathway, promising a potent lead compound for anticancer peptide drug development. Our work may shed new light as well on the design of other classes of MDM2/MDMX antagonists as P53 activators for therapeutic use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 21807112 (to Xiang Li), No. 82030062 (to Wuyuan Lu), Nos. 91849129 and 22077078 (to Honggang Hu), and Shanghai Rising-Star Program (to Xiang Li, China). Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript and the contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.06.010.

Contributor Information

Marzena Pazgier, Email: mpazgier@ihv.umaryland.edu.

Honggang Hu, Email: huhonggang_fox@msn.com.

Wuyuan Lu, Email: luwuyuan@fudan.edu.cn.

Author contributions

Wuyuan Lu conceived and designed the study. Xiang Li, Neelakshi Gohain, Si Chen, Yinghua Li, Xiaoyuan Zhao, Bo Li and William D. Tolbert performed the experiments. Honggang Hu and Wangxiao He helped with study design and manuscript editing. Wuyuan Lu, Marzena Pazgier and Xiang Li analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ding L., Ley T.J., Larson D.E., Miller C.A., Koboldt D.C., Welch J.S. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine A.J., Oren M. The first 30 years of P53: growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:749–758. doi: 10.1038/nrc2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane D.P. Cancer. P53, guardian of the genome. Nature. 1992;358:15–16. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogelstein B., Lane D., Levine A.J. Surfing the P53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vousden K.H., Lane D.P. P53 in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:275–283. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haupt Y., Maya R., Kazaz A., Oren M. MDM2 promotes the rapid degradation of P53. Nature. 1997;387:296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honda R., Tanaka H., Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor P53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420:25–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shvarts A., Steegenga W.T., Riteco N., van Laar T., Dekker P., Bazuine M. MDMX: a novel P53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. EMBO J. 1996;15:5349–5357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marine J.C., Dyer M.A., Jochemsen A.G. MDMX: from bench to bedside. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:371–378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wade M., Li Y.C., Wahl G.M. MDM2, MDMX and P53 in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:83–96. doi: 10.1038/nrc3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martins C.P., Brown-Swigart L., Evan G.I. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of P53 restoration in tumors. Cell. 2006;127:1323–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ventura A., Kirsch D.G., McLaughlin M.E., Tuveson D.A., Grimm J., Lintault L. Restoration of P53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue W., Zender L., Miething C., Dickins R.A., Hernando E., Krizhanovsky V. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by P53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones S.N., Roe A.E., Donehower L.A., Bradley A. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of P53. Nature. 1995;378:206–208. doi: 10.1038/378206a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montes de Oca Luna R., Wagner D.S., Lozano G. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of P53. Nature. 1995;378:203–206. doi: 10.1038/378203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parant J., Chavez-Reyes A., Little N.A., Yan W., Reinke V., Jochemsen A.G. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm4-null mice by loss of TrP53 suggests a nonoverlapping pathway with MDM2 to regulate P53. Nat Genet. 2001;29:92–95. doi: 10.1038/ng714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoo K.H., Verma C.S., Lane D.P. Drugging the P53 pathway: understanding the route to clinical efficacy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:217–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown C.J., Lain S., Verma C.S., Fersht A.R., Lane D.P. Awakening guardian angels: drugging the P53 pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:862–873. doi: 10.1038/nrc2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shangary S., Wang S. Small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2‒P53 protein‒protein interaction to reactivate P53 function: a novel approach for cancer therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:223–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q., Zeng S.X., Lu H. Targeting P53‒MDM2‒MDMX loop for cancer therapy. Subcell Biochem. 2014;85:281–319. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9211-0_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Momand J., Zambetti G.P., Olson D.C., George D., Levine A.J. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the P53 protein and inhibits P53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliner J.D., Pietenpol J.A., Thiagalingam S., Gyuris J., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor P53. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y., Aguilar A., Bernard D., Wang S. Small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2‒P53 protein‒protein interaction (MDM2 inhibitors) in clinical trials for cancer treatment. J Med Chem. 2014;58:1038–1052. doi: 10.1021/jm501092z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phan J., Li Z., Kasprzak A., Li B., Sebti S., Guida W. Structure-based design of high-affinity peptides inhibiting the interaction of P53 with MDM2 and MDMX. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2174–2183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.073056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhan C., Lu W. Peptide activators of the P53 tumor suppressor. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:603–609. doi: 10.2174/138161211795222577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fasan R., Dias R.L., Moehle K., Zerbe O., Obrecht D., Mittl P.R. Structure‒activity studies in a family of beta-hairpin protein epitope mimetic inhibitors of the P53‒HDM2 protein‒protein interaction. Chembiochem. 2006;7:515–526. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fasan R., Dias R.L., Moehle K., Zerbe O., Vrijbloed J.W., Obrecht D. Using a beta-hairpin to mimic an alpha-helix: cyclic peptidomimetic inhibitors of the P53‒HDM2 protein‒protein interaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:2109–2112. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harker E.A., Daniels D.S., Guarracino D.A., Schepartz A. Beta-peptides with improved affinity for hDM2 and hDMX. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:2038–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C., Pazgier M., Liu M., Lu W.Y., Lu W. Apamin as a template for structure-based rational design of potent peptide activators of P53. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:8712–8715. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kritzer J.A., Zutshi R., Cheah M., Ran F.A., Webman R., Wongjirad T.M. Miniature protein inhibitors of the P53‒hDM2 interaction. Chembiochem. 2006;7:29–31. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu B., Gilkes D.M., Chen J. Efficient P53 activation and apoptosis by simultaneous disruption of binding to MDM2 and MDMX. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8810–8817. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li C., Liu M., Monbo J., Zou G., Li C., Yuan W. Turning a scorpion toxin into an antitumor miniprotein. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13546–13548. doi: 10.1021/ja8042036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shangary S., Qin D., McEachern D., Liu M., Miller R.S., Qiu S. Temporal activation of P53 by a specific MDM2 inhibitor is selectively toxic to tumors and leads to complete tumor growth inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3933–3938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708917105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vassilev L.T., Vu B.T., Graves B., Carvajal D., Podlaski F., Filipovic Z. In vivo activation of the P53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C., Pazgier M., Li C., Yuan W., Liu M., Wei G. Systematic mutational analysis of peptide inhibition of the P53-MDM2/MDMX interactions. J Mol Biol. 2010;398:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pazgier M., Liu M., Zou G., Yuan W., Li C., Li C. Structural basis for high-affinity peptide inhibition of P53 interactions with MDM2 and MDMX. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4665–4670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900947106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wade M., Wahl G.M. Targeting Mdm2 and Mdmx in cancer therapy: better living through medicinal chemistry?. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1–11. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnolzer M., Alewood P., Jones A., Alewood D., Kent S.B. In situ neutralization in Boc-chemistry solid phase peptide synthesis. Rapid, high yield assembly of difficult sequences. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1992;40:180–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1992.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dawson P.E., Kent S.B. Synthesis of native proteins by chemical ligation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:923–960. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dawson P.E., Muir T.W., Clark-Lewis I., Kent S.B. Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pace C.N., Vajdos F., Fee L., Grimsley G., Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C., Pazgier M., Li J., Li C., Liu M., Zou G. Limitations of peptide retro-inverso isomerization in molecular mimicry. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19572–19581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhan C., Varney K., Yuan W., Zhao L., Lu W. Interrogation of MDM2 phosphorylation in P53 activation using native chemical ligation: the functional role of Ser17 phosphorylation in MDM2 reexamined. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6855–6864. doi: 10.1021/ja301255n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhan C., Zhao L., Wei X., Wu X., Chen X., Yuan W. An ultrahigh affinity d-peptide antagonist of MDM2. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6237–6241. doi: 10.1021/jm3005465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murshudov G.N., Vagin A.A., Dodson E.J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X., Tolbert W.D., Hu H.-G., Gohain N., Zou Y., Niu F. Dithiocarbamate-inspired side chain stapling chemistry for peptide drug design. Chem Sci. 2019;10:1522–1530. doi: 10.1039/c8sc03275k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dill K.A. Additivity principles in biochemistry. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:701–704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wells J.A. Additivity of mutational effects in proteins. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8509–8517. doi: 10.1021/bi00489a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X., Chen S., Zhang W.D., Hu H.G. Stapled helical peptides bearing different anchoring residues. Chem Rev. 2020;120:10079–10144. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown C.J., Quah S.T., Jong J., Goh A.M., Chiam P.C., Khoo K.H. Stapled peptides with improved potency and specificity that activate P53. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:506–512. doi: 10.1021/cb3005148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen X., Tai L., Gao J., Qian J., Zhang M., Li B. A stapled peptide antagonist of MDM2 carried by polymeric micelles sensitizes glioblastoma to temozolomide treatment through P53 activation. J Control Release. 2015;218:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao L., Lu W. Mirror image proteins. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014;22:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Craik D.J., Fairlie D.P., Liras S., Price D. The future of peptide-based drugs. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2013;81:136–147. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernal F., Tyler A.F., Korsmeyer S.J., Walensky L.D., Verdine G.L. Reactivation of the P53 tumor suppressor pathway by a stapled P53 peptide. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2456–2457. doi: 10.1021/ja0693587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moellering R.E., Cornejo M., Davis T.N., Del Bianco C., Aster J.C., Blacklow S.C. Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex. Nature. 2009;462:182–188. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schafmeister C.E., Po J., Verdine G.L. An all-hydrocarbon cross-linking system for enhancing the helicity and metabolic stability of peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5891–5892. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walensky L.D., Kung A.L., Escher I., Malia T.J., Barbuto S., Wright R.D. Activation of apoptosis in vivo by a hydrocarbon-stapled BH3 helix. Science. 2004;305:1466–1470. doi: 10.1126/science.1099191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bautista A.D., Appelbaum J.S., Craig C.J., Michel J., Schepartz A. Bridged beta(3)-peptide inhibitors of P53‒hDM2 complexation: correlation between affinity and cell permeability. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2904–2906. doi: 10.1021/ja910715u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang H., Curreli F., Zhang X., Bhattacharya S., Waheed A.A., Cooper A. Antiviral activity of alpha-helical stapled peptides designed from the HIV-1 capsid dimerization domain. Retrovirology. 2011;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takada K., Zhu D., Bird G.H., Sukhdeo K., Zhao J.J., Mani M. Targeted disruption of the BCL9/beta-catenin complex inhibits oncogenic Wnt signaling. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:148ra117. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Phillips C., Roberts L.R., Schade M., Bazin R., Bent A., Davies N.L. Design and structure of stapled peptides binding to estrogen receptors. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9696–9699. doi: 10.1021/ja202946k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.LaBelle J.L., Katz S.G., Bird G.H., Gavathiotis E., Stewart M.L., Lawrence C. A stapled BIM peptide overcomes apoptotic resistance in hematologic cancers. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2018–2031. doi: 10.1172/JCI46231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grossmann T.N., Yeh J.T., Bowman B.R., Chu Q., Moellering R.E., Verdine G.L. Inhibition of oncogenic Wnt signaling through direct targeting of beta-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17942–17947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208396109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baek S., Kutchukian P.S., Verdine G.L., Huber R., Holak T.A., Lee K.W. Structure of the stapled P53 peptide bound to Mdm2. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:103–106. doi: 10.1021/ja2090367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernal F., Wade M., Godes M., Davis T.N., Whitehead D.G., Kung A.L. A stapled P53 helix overcomes HDMX-mediated suppression of P53. Cancer Cell. 2011;18:411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown C.J., Quah S.T., Jong J., Goh A.M., Chiam P.C., Khoo K.H. Stapled peptides with improved potency and specificity that activate P53. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;15:506–512. doi: 10.1021/cb3005148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chang Y.S., Graves B., Guerlavais V., Tovar C., Packman K., To K.H. Stapled alpha-helical peptide drug development: a potent dual inhibitor of MDM2 and MDMX for P53-dependent cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E3445–E3454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Philippe G., Huang Y.H., Cheneval O., Lawrence N., Zhang Z., Fairlie D.P. Development of cell-penetrating peptide-based drug leads to inhibit MDMX: P53 and MDM2: P53 interactions. Biopolymers. 2016;106:853–863. doi: 10.1002/bip.22893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eckert D.M., Malashkevich V.N., Hong L.H., Carr P.A., Kim P.S. Inhibiting HIV-1 entry: discovery of d-peptide inhibitors that target the gp41 coiled-coil pocket. Cell. 1999;99:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schumacher T.N., Mayr L.M., Minor D.L., Jr., Milhollen M.A., Burgess M.W., Kim P.S. Identification of d-peptide ligands through mirror-image phage display. Science. 1996;271:1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu M., Li C., Pazgier M., Li C., Mao Y., Lv Y. d-peptide inhibitors of the P53–MDM2 interaction for targeted molecular therapy of malignant neoplasms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14321–14326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008930107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu M., Pazgier M., Li C., Yuan W., Li C., Lu W. A left-handed solution to peptide inhibition of the P53‒MDM2 interaction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:3649–3652. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhan C., Li C., Wei X., Lu W., Lu W. Toxins and derivatives in molecular pharmaceutics: drug delivery and targeted therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;90:101–118. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan S., Yan J., Liu D., Li X., Kang Q., You W. A nano-predator of pathological MDMX construct by clearable supramolecular gold(I)-thiol-peptide complexes achieves safe and potent anti-tumor activity. Theranostics. 2021;11:6833–6846. doi: 10.7150/thno.59020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.He W., Wang S., Yan J., Qu Y., Jin L., Sui F. Self-assembly of therapeutic peptide into stimuli-responsive clustered nanohybrids for cancer-targeted therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29:1807736. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201807736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brunger A.T. Free R value: cross-validation in crystallography. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:366–396. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.