Abstract

Background:

Comorbid stress-induced mood and alcohol use disorders are increasingly prevalent among female patients. Stress exposure can disrupt salience processing and goal-directed decision making, contributing to persistent maladaptive behavioral patterns; these and other stress-sensitive cognitive and behavioral processes rely on dynamic and coordinated signaling by midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei. Considering the role of social trauma in the trajectory of these debilitating psychopathologies, identifying vulnerable thalamic cells may provide guidance for targeting persistent stress-induced symptoms.

Methods:

A novel behavioral protocol traced the progression from social trauma to the development of social defensiveness and chronically escalated alcohol consumption in female mice. Recent cell activation – measured as cFos - was quantified in thalamic cells after safe social interactions, revealing stress-sensitive corticotropin releasing hormone-expressing (Crh+) anterior central medial thalamic (aCMT) cells. These cells were optogenetically stimulated during stress-induced social defensiveness and abstinence-escalated binge drinking.

Results:

Crh+ aCMT neurons exhibited substantial activation after social interactions in stress-naïve but not stressed female mice. Photoactivating Crh+ aCMT cells dampened stress-induced social deficits whereas inhibiting these cells increased social defensiveness in stress-naïve mice. Optogenetically activating Crh+ aCMT cells diminished abstinence-escalated binge alcohol drinking in female mice, regardless of stress history.

Conclusions:

This work uncovers a role for Crh+ aCMT neurons in maladaptive stress-induced social interactions and in binge drinking after forced abstinence in female mice. This molecularly-defined thalamic cell population may serve as a critical stress-sensitive hub for social deficits caused by exposure to social trauma and for patterns of excessive alcohol drinking in female populations.

Keywords: female chronic social defeat stress, thalamus, corticotropin releasing hormone, social interaction, alcohol, defensive behavior

Introduction

The debilitating repercussions of stress can manifest in distinct psychiatric disease trajectories, often according to gender; while mood disorders are more prevalent among women, alcohol use disorders (AUD) are more frequent in men (1–20). Yet, the gender gap in AUD prevalence is steadily closing as diagnostic rates increase in women (9, 21–24). Probing the etiology of this rise in AUDs reveals that mood disorders commonly precede the initiation of alcohol abuse (6, 7, 25). With a growing population of women diagnosed with comorbid mood and alcohol use disorders (26), translational animal models can serve as an important tool for examining the neural and behavioral maladaptations that contribute to stress-induced defensiveness, hypervigilance, and increased drinking in female subjects (27, 28).

Experiencing social trauma can result in the development of posttraumatic stress disorder, characterized by impaired fear inhibition in a safe context (29, 30). To model social trauma, translational mouse protocols employ chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) to forge a learned association between social cues and a pending attack. Repeated experiences with aggressive, dominant conspecifics lead to the rapid development of distinct defensive tactics accompanied by molecular and physiological disruptions that mirror some of the consequences of social trauma in humans (31–46). In female mice, CSDS yields a prominent defensive behavioral profile that persists for weeks after stress exposure, even during safe social interactions with a non-aggressive partner in a familiar non-threatening environment (46). Here, CSDS yields social defensiveness and increases alcohol consumption in female mice, modeling several cardinal symptoms of mood and alcohol use disorders in women who experience social trauma.

Considering its prominent involvement in hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic stress response mechanisms, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH; 47–52) has been examined extensively in translational preclinical experiments that model stress-induced psychiatric symptoms (42, 44, 45, 53–59). Cells that transcribe Crh - the gene encoding CRF - have been identified in the paraventricular thalamus (PVT) and the rostral intralaminar nuclei (rILN), which include the anterior central medial (aCMT), paracentral (PC), and central lateral thalamus (CL; 60–62). The PVT and rILN receive brainstem inputs from the ascending reticular activating system (63, 64) and provide both direct inputs to the central and basolateral amygdala (BLA), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and nucleus accumbens (NAc) as well as disynaptic accumbal inputs via the BLA or mPFC; many of these pathways are bidirectional, forming information processing loops (65–79). As such, PVT and rILN cells receiving arousal-related signals may functionally communicate salience to limbic targets that process emotional and reward-related information (80–87). Growing evidence implicates PVT/rILN cell populations and extended amygdala CRH signaling in reward processing and alcohol drinking (88); however, the functional role of thalamic Crh+ neurons remains unclear. Because midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei are instrumental in maintaining adaptive cognitive and behavioral processes that are derailed by stress-induced mood and drug use disorders (89–100), we hypothesize that thalamic Crh+ neurons contribute to the development of persistent stress-induced social deficits and dysregulated alcohol drinking in female mice.

Here, a translational model of female CSDS (46) is used to identify a novel population of aCMT neurons with suppressed cFos activation during safe social interactions in mice with a stress history. We hypothesized that a subpopulation of cells in the aCMT – those expressing Crh – may be specifically sensitive to social defeat stress and may be responsible for some of the persistent maladaptive behavioral repercussions of social defeat stress in female mice. After finding that Crh+ aCMT neurons are highly stress-sensitive, we optogenetically targeted these cells to reveal that: 1.) activation of Crh+ aCMT cells reverses stress-induced social avoidance and defensiveness, 2.) inhibition of these cells promotes social defensiveness in stress-naïve mice, 3.) prior social stress exposure increases chronic alcohol consumption in female mice, and 4.) that optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT neurons blunts forced abstinence-escalated alcohol consumption in control and stressed animals. In sum, the present work describes a novel stress-sensitive population of Crh+ aCMT neurons that was identified and characterized using an experimental approach that closely models the disease trajectory from social trauma to dysregulated sociability and alcohol drinking.

Methods and Materials

Animals:

Twelve-week-old Swiss Webster (CFW) female mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) were pair-housed with castrated CFW males (n=78 pairs). Six-to-eight-week-old C57BL/6J (B6; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) females were group-housed (n=10/26×48×15 cm cage) to serve as stimuli for either sociability or aggression tests (n=100). Experimental females included 10-12-week-old B6, CRH-ires-Cre, or CRH-ires-Cre/Ai9 reporter mice (100, 101). Animals were cared for according to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tufts University.

Home cage sociability testing:

Single-housed experimental mice were tested repeatedly for sociability toward non-aggressive B6 female mice during 1.5-minute home cage sociability tests (46). Social interaction time was quantified as the duration of social contact initiated by the experimental female. Defensiveness was quantified as total time spent escaping, kicking, avoiding, jumping, and displaying hypervigilance or social risk assessment, operationalized as time spent orienting toward but physically avoiding the social stimulus (46, 102, 103). Baseline social interaction times were used to assign experimental mice into counterbalanced defeat and control conditions. All social interactions were videotaped under dim red light and social and defensive behaviors were scored manually with Observer XT software (Noldus, Leesburg, VA, USA).

Female chronic social defeat stress:

As described previously (46), CFW females were tested for aggression toward unfamiliar group-housed B6 female intruder mice daily during 2-minute encounters. CFW females that bit >15 times during >3 consecutive tests were used as residents for 10-day CSDS. Twenty-four-hours pre-CSDS, aggressive CFW resident females and their male cage mates were housed in a cage (26x48x15 cm) divided in half by a perforated plastic partition (35, 46). Daily, CFW males were moved to holding cages before an unfamiliar experimental female was introduced into the territory of the aggressive resident female. Following the 5-minute defeat, the experimental female was housed adjacent to the resident aggressor, protected from further attack by the partition. Male-female CFW pairs were reunited between daily defeats to preserve female-directed aggression in resident mice. Daily for 10 days, each defeated experimental mouse was attacked by an unfamiliar CFW female and housed adjacent to that resident until the subsequent defeat. Non-defeated experimental control mice were housed adjacent to an unfamiliar CFW pair daily but were never defeated. Control and defeated mice were individually housed twenty minutes after the final defeat.

Continuous Access to Alcohol:

Mice received access to 20% ethyl alcohol (EtOH) and water as described previously (42, 43, 45). Alcohol solutions (w/v) were made weekly by diluting 95% EtOH in tap water (PHARMCO-AAPER, Brookfield, CT, USA), and presented daily on alternating sides of the cage lid. Bottles were weighed three hours into the dark photoperiod (1030h); fluid evaporation and spillage were controlled for by recording EtOH and water bottle weights from an empty cage and subtracting these values from daily experimental measurements. Body weights were recorded weekly to calculate grams of EtOH consumed per kilogram of body weight. Compared to intermittent access, continuous alcohol access yields moderate consumption (43), thereby allowing detection of bidirectional changes in intake.

Experiment 1: Alcohol consumption in control and defeated female mice:

Prior studies identify social stress as a powerful tool for modeling stress-escalated alcohol consumption in male mice (42–45). We employed CSDS in female mice to develop a novel model of social stress-escalated alcohol consumption. Beginning one week after their arrival, singly housed B6 females were habituated to vaginal lavage (104) for daily estrous cycle phase determination throughout the experiment. Ten days post-CSDS, mice received continuous access to alcohol for four weeks. The effects of forced alcohol abstinence were examined after the fourth week by providing mice with only water for 24-hours prior to alcohol reintroduction. After two hours of alcohol access, blood was collected from the submandibular vein and plasma was extracted to quantify blood ethanol concentration (BEC). Plasma samples (5 μL) were run in duplicate (AM1 Analyzer; Analox Instruments Ltd., Stourbridge, UK).

Experiment 2: aCMT cFos after social interactions in control or defeated female mice:

Female B6 mice were individually housed for one week. Sociability testing occurred twenty-four hours before and after the CSDS protocol. Mice were deeply anesthetized 1-hour after the second sociability test and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1xphosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Brain sliced containing the aCMT and BNST were selected for cFos immunohistochemistry (see Supplement).

Experiment 3: cFos in Crh+ aCMT cells after social interactions in control or defeated female mice

To examine if effects of CSDS on cFos activation were specific to Crh+ aCMT cells, we replicated and extended Experiment 2 in female CRH-ires-Cre/Ai9 mice that expressed endogenous tdTomato in Crh+ neurons.

Experiment 4: Optogenetic interrogation of Crh+ aCMT cells during pre- and post-CSDS social interactions and abstinence-induced binge alcohol drinking:

Female CRH-ires-Cre mice were infected with of adeno-associated virus (1-8x1012 vg/mL; UNC Vector Core, Chapel Hill, NC, USA) for Credependent expression of excitatory channelrhodopsin (ChR2; AAV2-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-mCherry-WPRE-pA) (105) or inhibitory halorhodopsin (NpHR; AAV2-EF1a-DIO-eNpHR3.0-mCherry) (106) in Crh+ aCMT cells (AP:−0.95; ML:0; DV:3.60). Optic fibers were implanted over the aCMT (16°; AP:−0.95, ML:1.00; DV:3.75).

Sociability during optogenetic stimulation of Crh+ aCMT neurons:

To allow mice a full range of motion during sociability tests, implanted optic fiber ferrules were attached to an optic fiber patch cord that connected to a rotary joint. This rotary joint was fitted to an overhead gimbal holder and a second patch cord connected the joint to the laser. Light pulses were controlled by a pulse generator (A.M.P.I, Jerusalem, Israel), and were administered for 2 minutes beginning 15 seconds prior to the 1.5-minute sociability tests. For pre-CSDS ChR2 stimulations, 50, 10, 5 or 1 ms 473 nm pulses were delivered at 2, 10, 20, or 40 Hz, respectively (107, 108). Pre-CSDS inhibitory 561 nm pulses were delivered to NpHR-expressing mice at frequencies and pulse widths of 2 Hz/50 ms, 2 Hz/125 ms or 20 Hz/5 ms (109, 110). Pre-CSDS laser control trials were conducted to determine if behavioral effects were induced by laser light alone; specifically, ChR2 mice received 561 nm pulses (40 Hz, 1 ms) while NpHR mice received 473 nm pulses (20 Hz, 5 ms). To mitigate wavelength-specific heat effects, power intensity was maintained at 0.5-2 mW and stimulations were restricted to <5 minutes (111). At the conclusion of Experiment 4, cFos was quantified after active or control laser pulse deliveries to examine the extent to which opsins might be affected by the control wavelength.

Pre-CSDS effects of laser pulse deliveries guided the selection of post-CSDS stimulation conditions; NpHR mice received 20 Hz stimulations whereas ChR2 mice received 40 Hz stimulations during post-CSDS sociability tests and alcohol drinking sessions after forced abstinence. Pre-CSDS sociability tests were conducted twice weekly for three weeks; post-CSDS tests occurred in the week following the final social defeat. All tests were conducted at least 48 hours apart and >24 hours after cages were cleaned.

Optogenetic stimulation of Crh+ aCMT cells during alcohol drinking:

Three days after their final sociability test, mice received continuous two-bottle choice access to water and 20% ethyl alcohol (w/v; EtOH). In the third week of alcohol access, home cages were fitted with custom-made stainless-steel lickometer panels, allowing alcohol and water sipper tubes to be presented through holes in the panel. Stainless steel mesh flooring was secured to the bottom of each panel to form a raised platform within each home cage. To drink, mice stood on the mesh platform and made tongue contact with the metal sipper tube. Each contact completed a circuit which registered as an event relayed via the lickometer controller to an interface (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) (112). Licks were recorded each time a closed circuit was detected with a minimum interlick interval sensitivity of 1-ms.

Mice received two days of continuous alcohol and water access during habituation to the lickometer panel (lickometer days 1 and 2). Three hours into the dark photoperiod on day 3, alcohol was replaced with a second water bottle and was subsequently reintroduced 24-hours later (day 4) to induce abstinence-induced alcohol binge drinking. Concurrent with alcohol reintroduction on day 4, NpHR-expressing females received 20 Hz 561 nm light pulses and ChR2-expressing mice received 40 Hz 473 nm pulses. Laser stimulations occurred over 2-hour sessions with 8×15-minute trials consisting of 5-minute laser ON, 10-minute laser OFF. This stimulation schedule was designed to detect: 1.) the effect of optogenetic stimulations on deprivation-induced binge drinking during the first five minutes after alcohol reintroduction, and 2.) potential changes in intake coinciding with laser offset. From day 5-11, animals received continuous access to alcohol and water and were subsequently alcohol-deprived on day 12. Alcohol was reintroduced on day 13 to quantify post-deprivation licking without optogenetic stimulations.

Effects of laser light pulses on aCMT cFos:

ChR2- or NpHR-expressing mice received stimulations in the home cage with or without concurrent sociability tests, respectively. One hour later, mice were transcardially perfused and tissue was collected to determine if ChR2 activation (473 nm, 40 Hz) induced cFos expression compared to control laser pulses (561 nm, 40 Hz) and to test if NpHR stimulation (561 nm, 20 Hz) reduced social cFos activation compared to control laser stimulations (473 nm, 20 Hz).

Statistical analyses:

The D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus K2 test for normality was conducted on raw or – for data sets containing zeroes - on y=(y+1) transformed data. When necessary, a logarithmic or square root transformation was applied to achieve normality before performing parametric statistical analyses; figures depict back-transformed data. The Geisser-Greenhouse correction was applied to repeated-measures (RM) and mixed analyses of variance (ANOVA). F tests of homoscedasticity preceded unpaired t tests of between-subject data sets with a single-level factor. For within-subject and mixed designs with multi-level factors, RM one-way, RM two-way ANOVA or mixed two-way ANOVA identified significant interactions and main effects. Significant omnibus tests were followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc comparisons between baseline and factor levels. Statistical analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism v.8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

See Supplement for additional details and experimental group numbers (Table S1).

Results

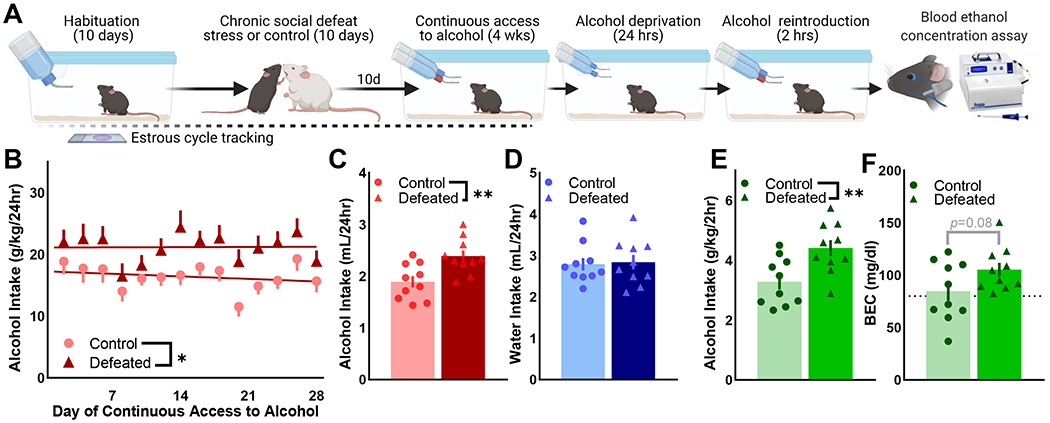

Experiment 1: Social defeat stress-increased chronic alcohol consumption and binge drinking after forced abstinence in female mice:

Chronically socially defeated wild-type B6 females consumed more alcohol compared to non-defeated controls (Fig. 1). Tracking estrous cycling through vaginal cytology revealed that neither stress nor alcohol intake resulted in protracted acyclicity (Fig. S1). Control and defeated mice achieved BECs >80 mg/dL in the two hours of alcohol access following 24-hour forced abstinence (Fig. 1), modeling a pattern of alcohol intake associated with high-risk binge drinking in women (113, 114).

Figure 1. Social stress and forced abstinence increase alcohol drinking in female mice.

(A) Wild-type C57BL/6J female mice were exposure to 10-day chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) or the non-defeated control condition (n=10/condition). Ten days after the final day of CSDS, mice received four weeks of continuous access to 20% ethyl alcohol (EtOH (w/v)) and water in the home cage. Alcohol was removed for 24-hours and reintroduced for 2-hours; submandibular blood was collected to determine blood EtOH concentration (BEC). Estrous cycle phase was tracked throughout (Fig. S1). (B) Defeated female mice consistently consumed more alcohol (g/kg/24hr) than control mice in the four weeks of alcohol access [F(1,18)=8.29, p=0.01]; data depicted as two-day group Means ± SEM. (C) Average daily alcohol intake was greater in defeated mice compared to controls [t(18)=3.22, p=0.0048] whereas (D) water intake was similar across conditions. (E) Defeated mice consumed more alcohol during two-hour access after forced abstinence [t(18)=3.065, p=0.0067], (F) producing a trend of increased BEC in defeated vs. control mice (p=0.08). Average 2-hour BECs were > 80 mg/dL (dotted line), indicative of a binge pattern of alcohol intake in control and defeated mice. (C, D) Data points depict four-week averages for individual mice; bars represent four-week group Mean ± SEM. (E, F) Data points are individual mice; bars represent the group Mean ± SEM. * p <0.05, ** p<0.01 control vs. defeated

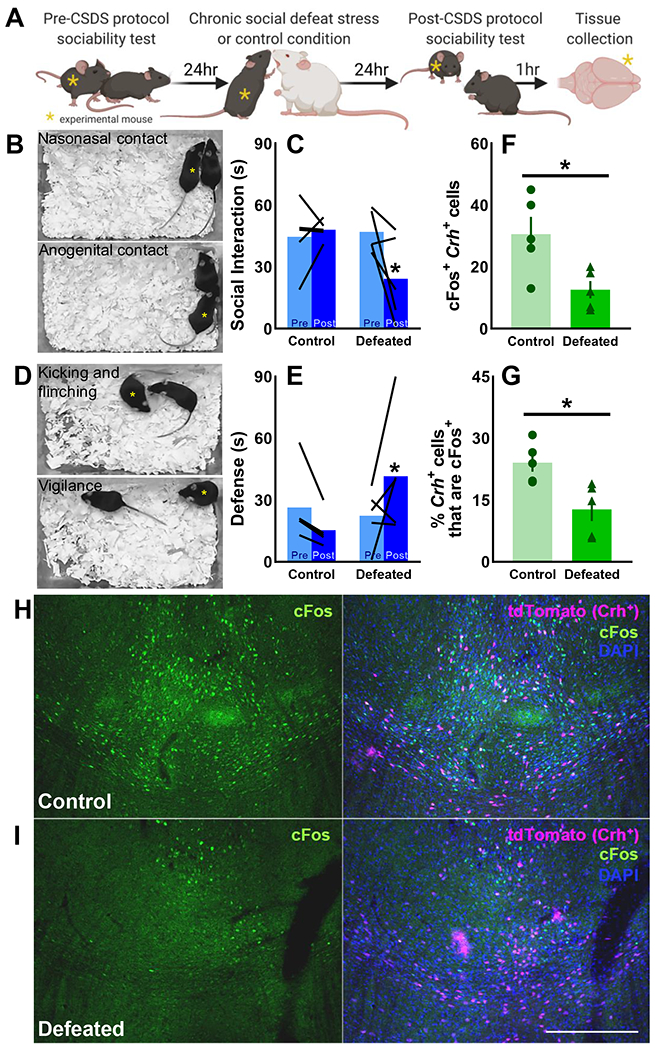

Experiments 2 and 3: CSDS reduced cFos in Crh+ aCMT cells after safe social interactions:

In B6 female mice, CSDS exposure reduced time spent socially interacting, increased defensive behaviors, and reduced the number of cFos+ cells in the anterior central medial thalamus (aCMT) compared to stress-naive control mice (Fig. S2). Colocalization of cFos and the endogenous fluorescent Crh-reporting protein - tdTomato - (Fig. S3, S4) was quantified in control and defeated CRH-ires-Cre/Ai9 mice after safe social interactions. As in wild-type mice (Fig. S2), CSDS reduced social interactions (Fig. 2A–C) and increased defensive behaviors (Fig. 2D–E) in female CRH-ires-Cre/Ai9 mice. Tissue collected from these animals revealed fewer aCMT cells with colocalized cFos and Crh-reporter and a reduction in the percentage of activated Crh+ aCMT cells in defeated compared to control mice (Fig. 2F–I). CSDS had no effect on cFos activation in Crh+ neurons within the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), suggesting a regionally selective effect of CSDS on Crh+ cell populations (Fig. S5).

Figure 2. Chronic social defeat stress blunts social cFos activation in Crh+ aCMT cells.

(A) Female CRH-ires-Cre/Ai9 mice were tested for baseline sociability toward a safe social partner, then exposed to either 10-day chronic social defeat stress (CSDS; n=5 Defeated) or the 10-day control condition (n=5 Control. Sociability was retested the day after 10-day CSDS/control protocol; tissue was collected one hour later to examine colocalization of cFos with the endogenous Crh reporter protein, tdTomato, in anterior central medial thalamic (aCMT) cells. (B, C) CSDS reduced sociability, measured as cumulative nasonasal and anogenital contact time [F(1,8)=5.37, p=0.049] and (D, E) increased defensiveness, measured as total time spent kicking, flinching, and maintaining a vigilant-like pose [F(1,8)=5.56, p=0.046]. (B, D) Yellow asterisks indicate CRH-ires-Cre/Ai9 mice as they engage in representative social and defensive behaviors. (F) Colocalization of cFos and tdTomato in the aCMT was suppressed by CSDS [t(8)=2.87, p=0.021]. (G) A greater percentage of Crh+ aCMT cells were activated by safe social interactions in (H) control mice compared to (I) defeated individuals [t(8)=3.19, p=0.013]; (H, I) representative images taken at 10x magnification of (left panels) cFos (green) and (right panels) cFos colocalization with tdTomato (magenta) and DAPI counterstaining (blue); 200 μm scale bar. Data shown as individual values and as the group Mean ± SEM; *p<0.05 control vs. defeated

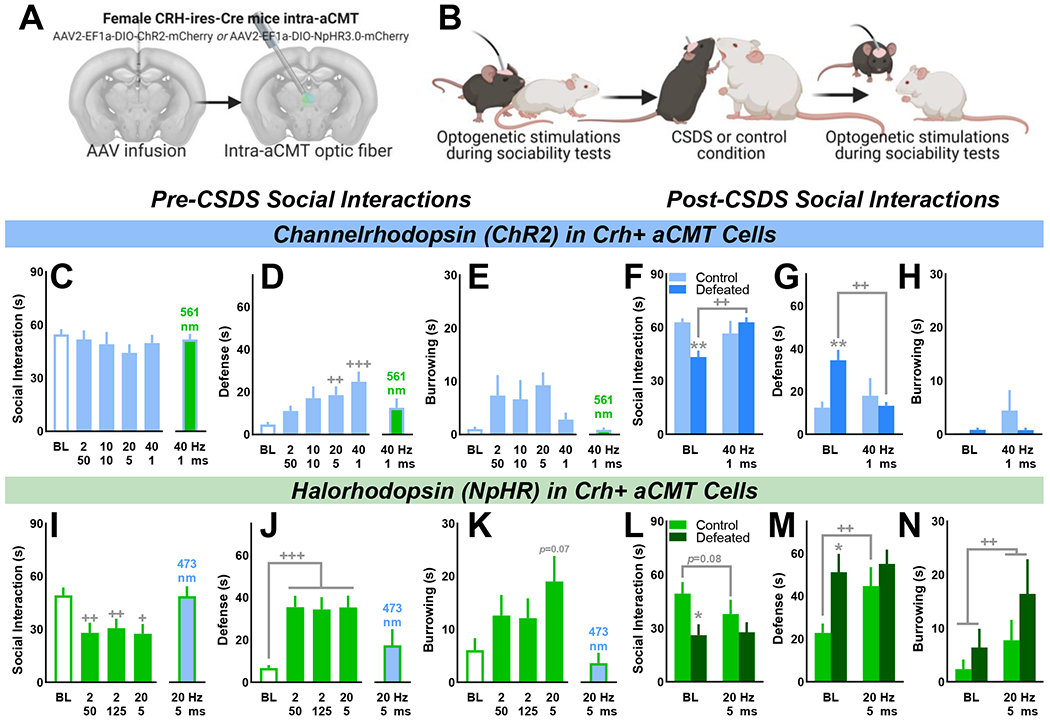

Experiment 4: Crh+ aCMT cell activation recovered sociability in chronically defeated female mice:

Female CRH-ires-Cre mice expressing ChR2 (Fig. 3A–B) received optogenetic stimulation to activate Crh+ aCMT neurons (Fig. S6). Activating these cells during sociability tests produced a frequency-dependent increase in defensiveness without affecting social interaction time, burrowing or walking compared to no-laser baseline (BL); control 561 nm light pulses had no effect on social interaction or walking durations (Fig. 3C–E; Fig. S8A). Defeat stress reduced BL social interactions and increased defensiveness compared to controls; activating Crh+ aCMT cells recovered sociability and reduced defensiveness in stressed mice without affecting burrowing (Fig. 3F–H; Video 1).

Figure 3. Optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT neurons reverses chronic social defeat stress-induced social deficits whereas optogenetic inhibition produces a defeat-like phenotype in stress-naïve female mice.

(A) Female CRH-ires-Cre mice received intra-aCMT AAV to express Cre-dependent channelrhodopsin (ChR2) or halorhodopsin (NpHR) in Crh+ neurons and were implanted with optic fibers targeting the aCMT. (B) Laser pulses were delivered during home cage safe social interactions to activate (ChR2) or inhibit (NpHR) Crh+ aCMT cells before and after 10-day chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) or the 10-day control procedure (ChR2: n=8 Control, n=10 Defeated; NpHR: n=8 Control, n=8 Defeated). (C) Before 10-day CSDS, neither 473 nm laser pulses nor control 561 nm laser pulses affected social interaction times in ChR2-expressing mice as compared with no-laser baseline (BL) tests. (D) Optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT cells produced a frequency-dependent increase in social defensiveness [F(4,68)=6.25, p<0.001] without affecting (E) burrowing. (F-H; BL) Compared with control mice, CSDS suppressed sociability [t(16)=4.35, p<0.001] and increased defensiveness [t(16)=3.70, p=0.002] without affecting burrowing. In defeated mice, Crh+ aCMT cell activation (F) recovered sociability [F(1,16)=11.63, p=0.004], and (G) diminished defensiveness [F(1,16)=9.00, p=0.009] without influencing (H) burrowing. (I) Compared to BL tests, inhibiting Crh+ aCMT cells with 561 nm light pulses reduced the duration of social interactions [F(3,45)=7.61, p<0.001], (J) increased defensive behaviors [F(3,45)=12.24, p<0.001], and (K) increased time spent burrowing [F(3,45)=4.07, p=0.012] whereas 473 nm pulses had no effect. (L-N) Post-CSDS, defeated mice interacted less with a social partner compared to control mice [t(14)=2.61, p=0.021] and were more defensive [t(14)=2.94, p=0.011]. Optogenetic inhibition of Crh+ aCMT cells produced a defeat-like phenotype in control mice by (F) increasing defensiveness [F(1,14)=5.35, p=0.036] while also (G) increasing time spent burrowing [F(1,14)=7.25, p=0.018]. (C-N) Data shown as the Mean ± SEM; Defeat vs. control: *p<0.05, **p<0.01; no stimulation (BL) vs. stimulation: +p<0.05, ++p<0.01, +++p<0.001. (A) Coronal brain images adapted from the Allen Institute Mouse Brain Atlas

Optogenetically inhibiting Crh+ aCMT cells produced a defeat-like phenotype in stress-naïve mice:

CRH-ires-Cre females expressing NpHR received optogenetic stimulations to inhibit Crh+ aCMT cells (Fig. S7). In stress-naïve control mice, inhibiting Crh+ aCMT cells produced a defeat-like phenotype by suppressing social interactions, escalating defensiveness, increasing burrowing, and decreasing walking compared to BL; control 473 nm laser pulses had no effect on sociability or walking (Fig. 3I–K; Fig. S8B; Video 2). CSDS suppressed BL social interactions and increased defensiveness (Fig. 3L, M); as observed prior to CSDS, inhibiting Crh+ aCMT cells increased defensiveness and burrowing and produced a trend toward social avoidance in controls (Fig. 3L–N).

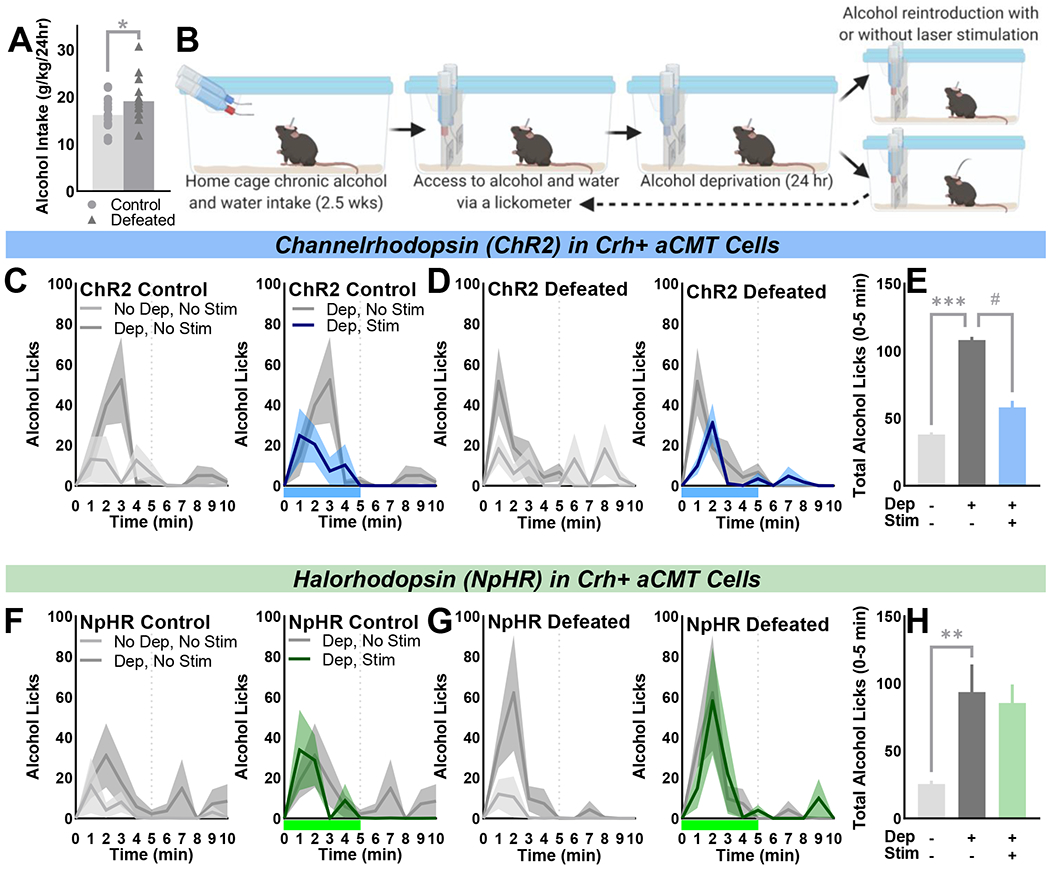

Optogenetically activating Crh+ aCMT cells reduced deprivation-escalated alcohol drinking:

CSDS increased daily home cage continuous access alcohol intake in CRH-ires-Cre mice (Fig. 4A). Drinking was subsequently measured in a lickometer setup (Fig. 4B) during drinking sessions preceded by unrestricted alcohol access (No Dep, No Stim; light grey traces) or beginning with alcohol reintroduction after 24-hour deprivation (Dep, No Stim; dark grey traces). Mice engaged in a pattern of abstinence-induced binge alcohol drinking during the initial five minutes after alcohol reintroduction (Fig. 4C–H; left panels). The effect of deprivation on alcohol intake was evident for up to two hours, particularly in socially defeated female mice (Fig. S9C, Fig. S10B).

Figure 4. Optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT neurons diminishes abstinence-induced binge alcohol drinking in female mice.

(A) Chronically socially defeated female CRH-ires-Cre mice drank more alcohol (g/kg/24hr) than stress-naïve controls [one-tailed: t(33)=1.99, p=0.027] when given (B) continuous access to water (blue bottle) and 20% ethyl alcohol ((w/v); red bottle) in their home cage. Cages were fitted with contact lickometer panels to count alcohol and water bottle licks during unrestricted access (No Dep). Mice were alcohol-deprived (Dep) for 24 hours prior to alcohol reintroduction and optogenetic activation (ChR2) or inhibition (NpHR) of Crh+ aCMT neurons (Dep, Stim) or during sessions without laser stimulations (Dep, No Stim). (C, D, F, G) Average alcohol licks/minute over the first 10 minutes of each drinking session; data shown as the group Mean ± SEM (line ± shaded areas) with light grey lines indicating No Dep, No Stim sessions, dark grey lines indicating Dep, No Stim sessions, blue or green lines denoting Dep, Stim of ChR2 or NpHR sessions, respectively. Blue or green bars beneath x-axes indicate 5-minute stimulation of ChR2 or NpHR, respectively. Vertical dotted lines indicate laser stimulation offset or the matching time point during No Stim sessions. (C, D; left panels) Control (n=8) and defeated (n=10) ChR2-expressing female mice demonstrated deprivation-escalated alcohol drinking during the first five minutes of drinking during Dep vs. No Dep sessions [F(1,16)=17.37, p<0.001]; (C, D; right panels) optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT neurons blunted deprivation-induced binge drinking in both control and defeated mice [F(1,16) = 5.72, p=0.029]. (E) Summarized effects of deprivation and Crh+ aCMT cell activation on the first five minutes of alcohol intake; data shown as Mean ± SEM collapsed over control and defeat conditions. (F, G; left panels) Control (n=9) and defeated (n=8) NpHR-expressing mice exhibited deprivation-escalated alcohol drinking during the first five minutes of Dep vs. No Dep sessions [F(1,15) =11.33, p=0.004]. (F, G, right panels) Optogenetic inhibition of Crh+ aCMT neurons had no effect on deprivation-escalated intake. (H) Summary of effects of alcohol deprivation and optogenetic inhibition on alcohol licking during the first five minutes of each session type in NpHR-expressing mice; data depicted as Mean ± SEM collapsed over control and defeat groups. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 deprivation effect; # p<0.05 stimulation effect.

To examine the effect of Crh+ aCMT cell stimulation on deprivation-escalated drinking, the onset of laser pulse deliveries coincided with alcohol reintroduction (Dep, Stim; blue and green traces; Fig. 4C, D, F, G; right panels). Stimulations occurred for two hours with 8×15-minute trials, each consisting of 5-min laser ON, 10-min laser OFF (Fig. S11). Optogenetically activating Crh+ aCMT cells blunted binge drinking during the first five minutes of alcohol access (Fig. 4C, D; right panels; Fig. S9B). Alcohol intake was suppressed throughout the two-hour stimulation protocol (Fig. S9D) and recovered after cessation of laser pulse deliveries (Fig. S9F, H). Optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT cells had no effect on water consumption (Fig. S9B–H). In NpHR mice, optogenetic inhibition of Crh+ aCMT cells had no effect on deprivation-escalated alcohol consumption or concurrent water intake (Fig. 4F–H; Fig. S10C, D).

cFos was quantified as a readout for laser stimulation effects. ChR2 mice exhibited increased cFos activation in response to 473 nm, 40 Hz stimulations compared to 561 nm pulses (Fig. S6). NpHR mice exhibited reduced cFos during social interactions paired with 561 nm light pulses compared to 473 nm stimulations (Fig. S7). Examination of viral expression revealed Crh+ projections from the midline and intralaminar thalamus (Fig. S12) to the mPFC, NAc, lateral septum, BNST, and BLA (Fig. S13).

Discussion

Traumatic social stress can lead to the development of mood disorders and dysregulated alcohol drinking, particularly among female patient populations (6, 7). Here, a translational model of this disease trajectory revealed a population of Crh+ anterior central medial thalamic (aCMT) cells that are rendered hypoactive – as measured by cFos, a correlate of recent neuronal activity - by social defeat stress exposure in female mice. Optogenetically activating Crh+ aCMT neurons recovered sociability in chronically socially defeated female mice and blunted alcohol abstinence-induced binge drinking. Interestingly, this high-frequency activation of Crh+ aCMT neurons increased defensiveness in stress-naïve mice. These opposing outcomes of high-frequency stimulations could reflect a stress-induced deviation from adaptive Crh+ aCMT cell firing patterns that ultimately shifts the stimulation-effect curve for defensive behaviors. Longitudinal in vivo calcium imaging and electrophysiology studies in both male and female mice will help to explore such predictions and provide greater insight into the real-time effects of ongoing stress exposure and the long-term consequences of social trauma within this cell population.

In stress-naïve female mice, optogenetically inhibiting Crh+ aCMT neurons elicited defensiveness to mimic defeat-like phenotype. The same stimulation conditions reduced exploratory locomotion during social interactions without suppressing other measures of motor activity (e.g., burrowing, defensive behaviors, licking). While locomotor suppression may contribute to the observed reduction in thalamic cFos in defeated mice, it is unlikely that photoinhibition blunts motor activity to produce a defeat-like phenotype. Rather, the present optogenetics studies and examinations of locomotion in stressed females during non-social probes (46) would indicate that diminished locomotor activity is caused by the presence of a social partner. This evidence supports a specific role for stress-sensitive Crh+ aCMT neurons in mediating adaptive sociability in female mice.

Female mice that were subjected to social defeat stress consumed more alcohol compared to stress-naïve individuals, as reported previously in male mouse models (42–45, 115–118). Mice with a history of chronic voluntary alcohol consumption also engaged in intense binge drinking during the initial five minutes of alcohol access after a period of forced abstinence. Optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT neurons reduced abstinence-induced binge drinking without affecting concurrent water intake; this effect was only observed during the two-hour optogenetic stimulation protocol and not in the hours of drinking following cessation of cell activation. Importantly, compensatory drinking bouts did not emerge during the ten-minute durations that separated five-minute epochs of optogenetic activation, suggesting that activation of Crh+ aCMT cells may selectively and persistently lessen the negative affect that motivates binge drinking caused by acute cessation of chronic alcohol consumption. Suppression of alcohol intake during optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT cells was observed in both control and socially defeated mice, indicating that this cell population may be sensitive to a broad range of stressors that yield persistent, maladaptive affective states, including historical social trauma and involuntary abstinence from chronic alcohol consumption. Additional studies are required to further our understanding of relevant stress-sensitive thalamic nuclei; in particular, it will be crucial to determine if thalamic cell populations can be manipulated to counter the negative affective symptoms of alcohol withdrawal that contribute to relapse in patients with alcohol use disorders.

Social avoidance was apparent when Crh+ aCMT neurons were optogenetically inhibited. Easing inhibitory constraints on thalamic cells within thalamo-corticothalamic loops may disinhibit cortical interneurons and blunt corticothalamic afferents. Interestingly, a distinct population of thalamocortical cells - classified by the absence of dopamine D2 receptor gene expression (Drd2−) - is transiently hypoactive in response to acute stressors and social interactions (119). Determining the relationship between thalamic Drd2− and Crh+ cell populations will deepen our understanding of thalamic cell types and the functional and transcriptional characteristics of inherently dynamic, stress-sensitive neural ensembles with specific projection targets (120). Midline and intralaminar thalamic Crh+ cells projected to the mPFC, NAc, lateral septum, BNST, and BLA. Together, these target regions comprise corticolimbic networks that regulate reward and threat processing (121–128). Growing support implicates midline and rILN thalamic nuclei as hubs in a broader stress-sensitive network (e.g., mPFC, NAc, BNST, BLA; 59–79). As such, gene expression profiling could reveal targetable stress-sensitive transcription factors in molecularly defined thalamic cell populations that promote or maintain network-level gene expression changes and downstream behavioral repercussions of trauma (129–131).

The present work identifies a novel social stress-sensitive population of Crh+ aCMT neurons using a highly translational model of social trauma in female mice (46). Targeting this cell population with optogenetics revealed that: 1.) stress-naïve female mice become socially defensive when Crh+ aCMT neurons are inhibited, 2.) sociability is recovered in stress-exposed females that receive laser pulses activating Crh+ aCMT cells, 3.) social defeat stress promotes chronic alcohol consumption in female mice, 4.) acute forced abstinence from chronic alcohol access induces binge drinking when mice regain access to alcohol, and 5.) optogenetic activation of Crh+ aCMT neurons blunts abstinence-induced binge alcohol drinking. Together, the present studies implicate Crh+ aCMT neurons in social avoidance and defensiveness after stress exposure and in binge drinking induced by involuntary abstinence after chronic alcohol drinking. In a broader context, these findings point to Crh+ cells in the aCMT as a novel neuronal population that demands further consideration for its role in maintaining the persistent maladaptive affective states and behavioral repercussions that can result from social trauma and chronic alcohol use.

Supplementary Material

Key Resource Table

| Resource Type | Specific Reagent or Resource | Source or Reference | Identifiers | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add additional rows as needed for each resource type | Include species and sex when applicable. | Include name of manufacturer, company, repository, individual, or research lab. Include PMID or DOI for references; use “this paper” if new. | Include catalog numbers, stock numbers, database IDs or accession numbers, and/or RRIDs. RRIDs are highly encouraged; search for RRIDs at https://scicrunch.org/resources. | Include any additional information or notes if necessary. |

| Antibody | ||||

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-cFos | Millipore Sigma | F7799 | ||

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG AlexaFluor-488-conjugated | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. | 111-545-144 | ||

| Bacterial or Viral Strain | ||||

| AAV2-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-mCherry-WPRE-pA | University of North Carolina Vector Core | N/A | ||

| AAV2-EF1a-DIO-NpHR3.0-mCherry | University of North Carolina Vector Core | N/A | ||

| Chemical Compound or Drug | ||||

| 95% Ethyl Alcohol (ACS/USP Grade) | PHARMCO-AAPER | 111000190 | ||

| Ketamine | VedCo | CAS: 6740-88-1 | KETAVED (KETAMINE HCL 100MG) | |

| Xylazine | Patterson Veterinary | CAS: 7361-61-7 | AnaSed | |

| Carprofen | Patterson Veterinary | CAS: 53716-49-7 | Rimadyl Injectable | |

| Saline | Hospira | 00409-4888-12 | ||

| 4% Paraformaldehyde in 1xPBS | Alfa Aesar | CAS: 30525-89-4 | ||

| Phosphate buffered saline (10x) | Fisher Scientific | BP3991 | ||

| Triton X-100 | Millipore Sigma | CAS: 9002-93-1 | ||

| DAPI | Millipore Sigma | CAS: 28718-90-3 | ||

| Krystalon | Millipore Sigma | 64969 | ||

| Cresyl violet | Millipore Sigma | C5042 CAS: 10510-54-0 | ||

| Commercial Assay Or Kit | ||||

| Alcohol analyzer | Analox | AM1 | ||

| Alcohol analyzer reagent | Analox | GMRD-113 | ||

| Alcohol analyzer standard | Analox | GMRD-110(100) | ||

| Organism/Strain | ||||

| Swiss webster (CFW) mice (male and female) | Charles River Laboratories | 024 | Males castrated by Charles River Laboratories | |

| C57BL/6J mice (female) | The Jackson Laboratory | 000664 | ||

| B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sor tm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J (Ai9) mice | The Jackson Laboratory | 007909 | Bred to CRH-ires-Cre mice in-house | |

| B6(Cg)-Crh tm1(cre)Zjh/J (CRH-ires-Cre) mice | The Jackson Laboratory | 012704 | Experimental mice bred in-house | |

| Software; Algorithm | ||||

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software, Inc | v. 8.0 and v. 9.0 | ||

| The Observer XT | Noldus Information Technology | v. 12.0 | ||

| FIJI ImageJ | Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E et al. (2012): Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676-682, PMID 22743772, doi:10.1038/nmeth.2019 | v. 1.53e | https://imagej.net/Fiji | |

| ZEN Lite | Zeiss | N/A | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/products/microscope-software/zen-lite.html | |

| MATLAB | Mathworks | R2019b | ||

| Med-PC | Med Associates Inc | IV | ||

| Biorender | Biorender | N/A | Biorender.com | |

| Other | ||||

| Optic fiber implants | Doric lenses | MFC_200/240-0.22_5mm_ZF1.25_FLT | ||

| Mating sleeve | Doric lenses | SLEEVE_ZR_1.25_BK | ||

| Patch cords | Doric lenses | MFP FC-FC and FC-ZF1.25 | ||

| Rotary joint | Doric lenses | FRJ_1×1_FC | ||

| Gimbal | Doric lenses | GH_FRJ | ||

| Stereotaxic frame | Kopf | Model 902 | ||

| Stereotaxic syringe pump | World Precision Instruments | UMP3T-2 | ||

| Sub-microliter syringe | World Precision Instruments | NANOFIL (10) | ||

| Microinfusion needles (beveled) | World Precision Instruments | NF35BV-2 | ||

| Submandibular mouse lancet | MEDIpoint Inc. | Goldenrod 3 mm | ||

| Dental cement | Stoelting Co. | 51459 | ||

| Lasers | CrystaLaser | 473 nm, 561 nm | ||

| Pulse generator | A.M.P.I. | Master-8 | ||

| Lickometer insert | Med Associates | ENV-350RM | ||

| Lickometer controller | Med Associates | ENV-250B | ||

| Interface module, connection panel | Med Associates | DIG-716B, SG-716 | ||

| Home cage lickometer panel | Machined in-house | N/A | ||

| Video camera | Logitech | C920 | ||

| Microscope | Zeiss | AxioImager Z1 | ||

| Microscope camera | Zeiss | AxioCam Mrm v.3.0 | ||

| Cryostat | Leica | CM3050 | ||

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant Nos. F31AA025827 and F32MH125634 [to ELN] and Grant Nos. R01AA013983 and R01DA031734 [to KAM]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Elizabeth Holly for her comments during manuscript preparation and Mr. Tom Sopko for his technical expertise. Figure timelines were created in biorender.com.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kessler RC (2003): Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 74:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC (1997): The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol. 48:191–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995): Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 52:1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB (1993): Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord. 29:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL, Schultz LR (1997): Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 54:1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonne SC, Back SE, Zuniga CD, Randall CL, Brady KT (2003): Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Addict. 12:412–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehavot K, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Kaysen D, Simpson TL (2014): Gender differences in relationships among PTSD severity, drinking motives, and alcohol use in a comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 28:42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, Mudar P (1992): Stress and alcohol-use - moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. J Abnorm Psychol. 101:139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT (2010): Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 33:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolen-Hoeksema S (2004): Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clin Psychol Rev. 24:981–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramikie TS, Ressler KJ (2018): Mechanisms of sex differences in fear and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 83:876–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sannibale C, Hall W (2001): Gender-related symptoms and correlates of alcohol dependence among men and women with a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 20:369–383. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinha R (2008): Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1141:105–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinha R (2009): Stress and addiction: A dynamic interplay of genes, environment, and drug intake. Biol Psychiatry. 66:100–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slopen N, Williams DR, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE (2011): Sex, stressful life events, and adult onset depression and alcohol dependence: Are men and women equally vulnerable? Soc Sci Med. 73:615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ (2019): Sex differences and the neurobiology of affective disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 44:111–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas SE, Bacon AK, Randall PK, Brady KT, See RE (2011): An acute psychosocial stressor increases drinking in non-treatment-seeking alcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 218:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uhart M, Chong RY, Oswald L, Lin P-I, Wand GS (2006): Gender differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 31:642–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uhart M, Wand GS (2009): Stress, alcohol and drug interaction: An update of human research. Addict Biol. 14:43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valentino RJ, Bangasser D, Van Bockstaele EJ (2013): Sex-biased stress signaling: The corticotropin-releasing factor receptor as a model. Mol Pharmacol. 83:737–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner FA, Anthony JC (2007): Male-female differences in the risk of progression from first use to dependence upon cannabis, cocaine, and alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 86:191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grucza RA, Norberg K, Bucholz KK, Bierut LJ (2008): Correspondence between secular changes in alcohol dependence and age of drinking onset among women in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 32:1493–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, Ruan WJ, et al. (2017): Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013 results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 74:911–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker JM, Taylor JR (2019): Sex differences in incentive motivation and the relationship to the development and maintenance of alcohol use disorders. Physiol Behav. 203:91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seo S, Beck A, Matthis C, Genauck A, Banaschewski T, Bokde ALW, et al. (2019): Risk profiles for heavy drinking in adolescence: Differential effects of gender. Addict Biol. 24:787–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF (2006): Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 67:247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker JB, Koob GF (2016): Sex differences in animal models: Focus on addiction. Pharmacol Rev. 68:242–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dzirasa K, Covington HE (2012): Increasing the validity of experimental models for depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1265:36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jovanovic T, Norrholm SD, Blanding NQ, Davis M, Duncan E, Bradley B, et al. (2010): Impaired fear inhibition is a biomarker of PTSD but not depression. Depress Anxiety. 27:244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.VanElzakker MB, Dahlgren MK, Davis FC, Dubois S, Shin LM (2014): From Pavlov to PTSD: The extinction of conditioned fear in rodents, humans, and anxiety disorders. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 113:3–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikulina EM, Hammer RP, Miczek KA, Kream RM (1999): Social defeat stress increases expression of mu-opioid receptor mRNA in rat ventral tegmental area. Neuroreport. 10:3015–3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, et al. (2006): Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 311:864–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miczek KA, Yap JJ, Covington HE III (2008): Social stress, therapeutics and drug abuse: Preclinical models of escalated and depressed intake. Pharmacol Ther. 120:102–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2010): Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 13:1161–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golden SA, Covington HE, Berton O, Russo SJ (2011): A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nat Protoc. 6:1183–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Litvin Y, Murakami G, Pfaff DW (2011): Effects of chronic social defeat on behavioral and neural correlates of sociality: Vasopressin, oxytocin and the vasopressinergic V1b receptor. Physiol Behav. 103:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nocjar C, Zhang J, Feng P, Panksepp J (2012): The social defeat animal model of depression shows diminished levels of orexin in mesocortical regions of the dopamine system, and of dynorphin and orexin in the hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 218:138–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holly EN, Boyson CO, Montagud-Romero S, Stein DJ, Gobrogge KL, DeBold JF, et al. (2016): Episodic social stress-escalated cocaine self-administration: Role of phasic and tonic corticotropin releasing factor in the anterior and posterior ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 36:4093–4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holly EN, Shimamoto A, DeBold JF, Miczek KA (2012): Sex differences in behavioral and neural cross-sensitization and escalated cocaine taking as a result of episodic social defeat stress in rats. Psychopharmacology. 224:179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimamoto A, Holly EN, Boyson CO, DeBold JF, Miczek KA (2015): Individual differences in anhedonic and accumbal dopamine responses to chronic social stress and their link to cocaine self-administration in female rats. Psychopharmacology. 232:825–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimamoto A, DeBold JF, Holly EN, Miczek KA (2011): Blunted accumbal dopamine response to cocaine following chronic social stress in female rats: Exploring a link between depression and drug abuse. Psychopharmacology. 218:271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norman KJ, Seiden JA, Klickstein JA, Han X, Hwa LS, DeBold JF, et al. (2015): Social stress and escalated drug self-administration in mice I. Alcohol and corticosterone. Psychopharmacology. 232:991–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwa LS, Holly EN, DeBold JF, Miczek KA (2016): Social stress-escalated intermittent alcohol drinking: Modulation by CRF-R1 in the ventral tegmental area and accumbal dopamine in mice. Psychopharmacology. 233:681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman EL, Leonard MZ, Arena DT, de Almeida RMM, Miczek KA (2018): Social defeat stress and escalation of cocaine and alcohol consumption: Focus on CRF. Neurobiol Stress. 9:151–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newman EL, Albrechet-Souza L, Andrew PM, Auld JG, Burk KC, Hwa LS, et al. (2018): Persistent escalation of alcohol consumption by mice exposed to brief episodes of social defeat stress: Suppression by CRF-R1 antagonism. Psychopharmacology. 235:1807–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newman EL, Covington HE, Suh J, Bicakci MB, Ressler KJ, DeBold JF, et al. (2019): Fighting females: Neural and behavioral consequences of social defeat stress in female mice. Biol Psychiatry. 86:657–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J (1981): Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science. 213:1394–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nemeroff CB (1996): The corticotropin-releasing factor hypothesis depression: New findings and new directions. Mol Psychiatry. 1:336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nemeroff CB, Widerlov E, Bissette G, Walleus H, Karlsson I, Eklund K, et al. (1984): Elevated concentrations of csf corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in depressed-patients. Science. 226:1342–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bremner JD, Licinio J, Darnell A, Krystal JH, Owens MJ, Southwick SM, et al. (1997): Elevated CSF corticotropin-releasing factor concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 154:624–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Binder EB, Nemeroff CB (2010): The CRF system, stress, depression and anxiety-insights from human genetic studies. Mol Psychiatry. 15:574–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salvatore M, Wiersielis KR, Luz S, Waxler DE, Bhatnagar S, Bangasser DA (2018): Sex differences in circuits activated by corticotropin releasing factor in rats. Horm Behav. 97:145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sapolsky RM, Uno H, Rebert CS, Finch CE (1990): Hippocampal damage associated with prolonged glucocorticoid exposure in primates. J Neurosci. 10:2897–2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sgoifo A, Koolhaas JM, Musso E, De Boer SF (1999): Different sympathovagal modulation of heart rate during social and nonsocial stress episodes in wild-type rats. Physiol Behav. 67:733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuchs E, Flugge G (2002): Social stress in tree shrews: Effects on physiology, brain function, and behavior of subordinate individuals. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 73:247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Covington HE, Miczek KA (2005): Intense cocaine self-administration after episodic social defeat stress, but not after aggressive behavior: Dissociation from corticosterone activation. Psychopharmacology. 183:331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koob GF, Volkow ND (2010): Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 35:217–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wood SK (2014): Cardiac autonomic imbalance by social stress in rodents: Understanding putative biomarkers. Front Psychol. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker LC, Cornish LC, Lawrence AJ, Campbell EJ (2019): The effect of acute or repeated stress on the corticotropin releasing factor system in the CRH-IRES-Cre mouse: A validation study. Neuropharmacology. 154:96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merchenthaler I, Vigh S, Schally AV, Stumpf WE, Arimura A (1984): Immunocytochemical localization of corticotropin releasing-factor (CRF)-like immunoreactivity in the thalamus of the rat. Brain Res. 323:119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng J, Long B, Yuan J, Peng X, Ni H, Li X, et al. (2017): A quantitative analysis of the distribution of CRH neurons in whole mouse brain. Front Neuroanat. 11:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Itoga CA, Chen YC, Fateri C, Echeverry PA, Lai JM, Delgado J, et al. (2019): New viral-genetic mapping uncovers an enrichment of corticotropin-releasing hormone-expressing neuronal inputs to the nucleus accumbens from stress-related brain regions. J Comp Neurol. 527:2474–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kinomura S, Larsson J, Gulyas B, Roland PE (1996): Activation by attention of the human reticular formation and thalamic intralaminar nuclei. Science. 271:512–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krout KE, Belzer RE, Loewy AD (2002): Brainstem projections to midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 448:53–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morison RS, Dempsey EW (1943): Mechanism of thalamocortical augmentation and repetition. Am J Physiol. 138:0297–0308. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Groenewegen HJ, Berendse HW (1994): The specificity of the nonspecific midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei. Trends Neurosci. 17:52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berendse HW, Groenewegen HJ (1991): Restricted cortical termination fields of the midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 42:73–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berendse HW, Groenewegen HJ (1990): Organization of the thalamostriatal projections in the rat, with special emphasis on the ventral striatum. J Comp Neurol. 299:187–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Steriade M, Glenn LL (1982): Neocortical and caudate projections of intralaminar thalamic neurons and their synaptic excitation from midbrain reticular core. J Neurophysiol. 48:352–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saalmann YB (2014): Intralaminar and medial thalamic influence on cortical synchrony, information transmission and cognition. Front Syst Neurosci. 8:83–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van der Werf YD, Witter MP, Groenewegen HJ (2002): The intralaminar and midline nuclei of the thalamus: Anatomical and functional evidence for participation in processes of arousal and awareness. Brain Res Rev. 39:107–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yasukawa T, Kita T, Xue Y, Kita H (2004): Rat intralaminar thalamic nuclei projections to the globus pallidus: A biotinylated dextran amine anterograde tracing study. J Comp Neurol. 471:153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li S, Kirouac GJ (2008): Projections from the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus to the forebrain, with special emphasis on the extended amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 506:263–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vertes RP, Hoover WB, Rodriguez JJ (2012): Projections of the central medial nucleus of the thalamus in the rat: Node in cortical, striatal and limbic forebrain circuitry. Neuroscience. 219:120–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hintzen A, Pelzer EA, Tittgemeyer M (2018): Thalamic interactions of cerebellum and basal ganglia. Brain Struct Funct. 223:569–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Giménez-Amaya JM, McFarland NR, De Las Heras S, Haber SN (1995): Organization of thalamic projections to the ventral striatum in the primate. J Comp Neurol. 354:127–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Finch DM (1996): Neurophysiology of converging synaptic inputs from the rat prefrontal cortex, amygdala, midline thalamus, and hippocampal formation onto single neurons of the caudate/putamen and nucleus accumbens. Hippocampus. 6:495–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xia S-h, Yu J, Huang X, Sesack SR, Huang YH, Schlüter OM, et al. (2020): Cortical and thalamic interaction with amygdala-to-accumbens synapses. J Neurosci. 40:7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dong P, Wang H, Shen X-F, Jiang P, Zhu X-T, Li Y, et al. (2019): A novel cortico-intrathalamic circuit for flight behavior. Nat Neurosci. 22:941–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hayes JP, Vanelzakker MB, Shin LM (2012): Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: A review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Front Integr Neurosci. 6:89–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Threlfell S, Lalic T, Platt NJ, Jennings KA, Deisseroth K, Cragg SJ (2012): Striatal dopamine release is triggered by synchronized activity in cholinergic interneurons. Neuron. 75:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rikhye RV, Gilra A, Halassa MM (2018): Thalamic regulation of switching between cortical representations enables cognitive flexibility. Nat Neurosci. 21:1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cover KK, Gyawali U, Kerkhoff WG, Patton MH, Mu C, White MG, et al. (2019): Activation of the rostral intralaminar thalamus drives reinforcement through striatal dopamine release. Cell Rep. 26:1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Francoeur MJ, Wormwood BA, Gibson BM, Mair RG (2019): Central thalamic inactivation impairs the expression of action- and outcome-related responses of medial prefrontal cortex neurons in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 50:1779–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kato S, Fukabori R, Nishizawa K, Okada K, Yoshioka N, Sugawara M, et al. (2018): Action selection and flexible switching controlled by the intralaminar thalamic neurons. Cell Rep. 22:2370–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhu Y, Nachtrab G, Keyes PC, Allen WE, Luo L, Chen X (2018): Dynamic salience processing in paraventricular thalamus gates associative learning. Science. 362:423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zilverstand A, Huang AS, Alia-Klein N, Goldstein RZ (2018): Neuroimaging impaired response inhibition and salience attribution in human drug addiction: A systematic review. Neuron. 98:886–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Levine OB, Skelly MJ, Miller JD, DiBerto JF, Rowson SA, Rivera-Irizarry JK, et al. (2020): The paraventricular thalamus provides a polysynaptic brake on limbic Crf neurons to sex-dependently blunt binge alcohol drinking and avoidance behavior. bioRxiv.2020.2005.2004.075051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Beas BS, Wright BJ, Skirzewski M, Leng Y, Hyun JH, Koita O, et al. (2018): The locus coeruleus drives disinhibition in the midline thalamus via a dopaminergic mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 21:963–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Do-Monte FH, Kirouac GJ (2017): Boosting of thalamic D2 dopaminergic transmission: A potential strategy for drug-seeking attenuation. eNeuro. 4:e0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Do-Monte FH, Quinones-Laracuente K, Quirk GJ (2015): A temporal shift in the circuits mediating retrieval of fear memory. Nature. 519:460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Do-Monte FH, Minier-Toribio A, Qinones-Laracuente K, Medina-Colon EM, Quirk GJ (2017): Thalamic regulation of sucrose seeking during unexpected reward omission. Neuron. 94:388–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hsu DT, Kirouac GJ, Zubieta J, Bhatnagar (2014): Contributions of the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the regulation of stress, motivation, and mood. Front Behav Neurosci. 8:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kirouac (2021): The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus as an integrating and relay node in the brain anxiety network. Front Behav Neurosci. 15: 627633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Padilla-Coreano N, Do-Monte FH, Quirk GJ (2012): A time-dependent role of midline thalamic nuclei in the retrieval of fear memory. Neuropharmacology. 62:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Penzo MA, Gao C (2021): The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus: An integrative node underlying homeostatic behavior. Trends Neurosci. 10.1016/j.tins.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Penzo MA, Robert V, Tucciarone J, De Bundel D, Wang M, Van Aelst L, et al. (2015): The paraventricular thalamus controls a central amygdala fear circuit. Nature. 519:456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rowson SA, Pleil KE (2021): Influences of stress and sex on the paraventruclar thalamus: Implications for motivated behavior. Front Behav Neurosci. 15: 636203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhou K, Zhu L, Hou G, Chen X, Chen B, Yang C, et al. (2021): The contribution of thalamic nuclei in salience processing. Front Behav Neurosci. 15:634618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, et al. (2010): A robust and high-throughput cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 13:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, et al. (2011): A resource of Cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 71:995–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Blanchard DC, Griebel G, Pobbe R, Blanchard RJ (2011): Risk assessment as an evolved threat detection and analysis process. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 35:991–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Duque-Wilckens N, Steinman MQ, Busnelli M, Chini B, Yokoyama S, Pham M, et al. (2018): Oxytocin receptors in the anteromedial bed nucleus of the stria terminalis promote stress-induced social avoidance in female California mice. Biol Psychiatry. 83:203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McLean AC, Valenzuela N, Fai S, Bennett SA (2012): Performing vaginal lavage, crystal violet staining, and vaginal cytological evaluation for mouse estrous cycle staging identification. J Vis Exp.e4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cardin JA, Carlén M, Meletis K, Knoblich U, Zhang F, Deisseroth K (2009): Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature. 459: 663–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gradinaru V, Zhang F, Ramakrishnan C, Mattis J, Prakash R, Diester I (2010): Molecular and cellular approaches for diversifying and extending optogenetics. Cell. 141: 154–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu J, Lee HJ, Weitz AJ, Fang Z, Lin P, Choy M, et al. (2015): Frequency-selective control of cortical and subcortical networks by central thalamus. eLife. 4:e09215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Weitz AJ, Lee HJ, Choy M, Lee JH (2019): Thalamic input to orbitofrontal cortex drives brain-wide, frequency-dependent inhibition mediated by GABA and zona incerta. Neuron. 104: 1153–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sorokin JM, Davidson TJ, Frechette E, Abramian AM, Deisseroth K, Huguenard JR, Paz JT (2017): Bidirectional control of generalized epilepsy networks via rapid real-time switching of firing mode. Neuron. 93:194–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vesuna S, Kauvar IV, Richman E, Gore F, Oskotsky T, Sava-Segal C (2020) Deep posteromedial cortical rhythm in dissociation. Nature. 586:87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Owen SF, Liu MH, Kreitzer AC (2019): Thermal constraints on in vivo optogenetic manipulations. Nat Neurosci. 22:1061–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Newman EL, Gunner G, Huynh P, Gachette D, Moss SJ, Smart TG, et al. (2016): Effects of Gabra2 point mutations on alcohol intake: Increased binge-like and blunted chronic drinking by mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 40:2445–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fillmore MT, Jude R (2011): Defining “binge” drinking as five drinks per occasion or drinking to a 0.08% BAC: Which is more sensitive to risk?. Am J Addict. 20:468–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Holleran KM, Winder DG (2017): Preclinical voluntary drinking models for alcohol abstinence-induced affective disturbances in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 16:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Karlsson C, Schank JR, Rehman F, Stojakovic A, Bjork K, Barbier E, et al. (2017): Proinflammatory signaling regulates voluntary alcohol intake and stress-induced consumption after exposure to social defeat stress in mice. Addict Biol. 22:1279–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kudryavtseva N, Gerrits M, Avgustinovich DF, Tenditnik MV, Van Ree JM (2006): Anxiety and ethanol consumption in victorious and defeated mice: Effect of kappa-opioid receptor activation. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 16:504–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kudryavtseva NN, Madorskaya IA, Bakshtanovskaya IV (1991): Social success and voluntary ethanol-consumption in mice of C57BL/6J and CBA/Lac strains. Physiol Behav. 50:143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nelson BS, Sequeira MK, Schank JR (2018): Bidirectional relationship between alcohol intake and sensitivity to social defeat: Association with Tacr1 and Avp expression. Addict Biol. 23:142–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gao C, Leng Y, Ma J, Rooke V, Rodriguez-Gonzalez S, Ramakrishnan C, et al. (2020): Two genetically, anatomically and functionally distinct cell types segregate across anteroposterior axis of paraventricular thalamus. Nat Neurosci. 23:217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Phillips JW, Schulmann A, Hara E, Winnubst J, Liu C, Valakh V, et al. (2019): A repeated molecular architecture across thalamic pathways. Nat Neurosci. 22:1925–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gilpin NW, Weiner JL (2017): Neurobiology of comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol-use disorder. Genes Brain Behav. 16:15–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Elman I, Upadhyay J, Langleben DD, Albanese M, Becerra L, Borsook D (2018): Reward and aversion processing in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder: Functional neuroimaging with visual and thermal stimuli. Transl Psychiatry. 8:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Huang AS, Mitchell JA, Haber SN, Alia-Klein N, Goldstein RZ (2018): The thalamus in drug addiction: From rodents to humans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Koob G, Kreek MJ (2007): Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 164:1149–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.McEwen BS (2007): Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 87:873–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Price JL, Drevets WC (2010): Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 35:192–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhou T, Zhu H, Fan Z, Wang F, Chen Y, Liang H, et al. (2017): History of winning remodels thalamo-PFC circuit to reinforce social dominance. Science. 357:162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhu Y, Wienecke CFR, Nachtrab G, Chen X (2016): A thalamic input to the nucleus accumbens mediates opiate dependence. Nature. 530:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bagot RC, Cates HM, Purushothaman I, Lorsch ZS, Walker DM, Wang J, et al. (2016): Circuit-wide transcriptional profiling reveals brain region-specific gene networks regulating depression susceptibility. Neuron. 90:969–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.McCullough KM, Chatzinakos C, Hartmann J, Missig G, Neve RL, Fenster RJ, et al. (2020): Genome-wide translational profiling of amygdala Crh-expressing neurons reveals role for CREB in fear extinction learning. Nat Comm. 11:5180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lorsch ZS, Hamilton PJ, Ramakrishnan A, Parise EM, Salery M, et al. (2019) Stress resilience is promoted by Zfp189-driven transcriptional network in prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 22:1413–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.