Abstract

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is not only used to aid the diagnosis of lung cancer, but also help monitor recurrence and determine the prognosis of lung cancer as well as evaluate the therapeutic efficacy for lung cancer. However, studies have also shown that CEA is present at low levels in the serum of patients with benign lung diseases (BLD), which will interfere with the accurate judgment of the disease. Due to difference in sample size, detection methods, cutoff values and sources of BLD, the positive rate of CEA in BLD is different with different literature. Therefore, it is necessary to define CEA levels in patients of different BLD in a large sample study. 4796 patients with BLD were included in this study. The results showed that the CEA levels of 3.1% (149/4796) patients with BLD were elevated, with three cases exceeds 20 ng/mL (0.06%, 3/4796). The results from the literature showed that BLD had a mean positive rate of 5.99% (53/885) and only two cases had CEA above 20 ng/mL. The CEA elevations mainly distributed in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonitis and interstitial lung disease and significantly correlated with age of patients (OR 2.69, 95% CI 1.94–3.73, p < 0.001). Pulmonary tuberculosis (7/1311, 0.53%) had the lowest positive rate of CEA elevations while pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (6/27, 22.22%) had the highest positive rate. The majority of patients with abnormally elevated CEA levels had multiple underlying diseases, mainly diseases of the circulatory system (42.28% [63/149]), endocrine diseases (26.85% [40/149]), and respiratory or heart failure (24.16% [36/149]. In endocrine diseases, 87.5% (35/40) of patients had diabetes. In conclusion, CEA is present at a low positive rate in the serum of patients with BLD, but few exceed 20 ng/mL. For lung disease patients, if CEA levels rise, we should carry out comprehensive analysis of types of lung diseases, age of patients, and comorbid diseases.

Subject terms: Cancer, Medical research, Oncology

Introduction

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was initially used to aid the diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma and other gastrointestinal tumors and monitor progression of these diseases. However, with advances in cancer diagnostics and therapy, CEA has become more widely used clinically beyond gastrointestinal tumors1. It is not only used to aid the diagnosis of lung cancer, but also help monitor recurrence and determine the prognosis of lung cancer as well as evaluate the therapeutic efficacy for lung cancer2. A prospective cohort study has demonstrated that a ≥ 14% reduction in CEA levels could predict objective response and progression-free survival (PFS), but not overall survival (OS)3. Recent studies have shown that CEA is closely associated with EGFR mutational status of lung cancer as well as with the efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKI)4,5. In EGFR-mutated patients, initial CEA levels and CEA levels post progression have different prognostic values6.

Studies have also shown that CEA is present at low levels in the serum of patients with nonmalignant diseases and many factors affect the serum CEA levels, including physiologic, metabolic, and circulatory factors as well as detection methods7. A previous study8 showed that idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients experience a rise in CEA levels. Immunohistochemical study8 have revealed that CEA is expressed in metaplasic bronchial epithelial cells and type II alveolar epithelial cells, indicating that apart from IPF, CEA levels may also increase in other lung diseases. With the application of immunotherapeutic agents and molecularly targeted drugs in lung cancer therapy, drug-associated lung injury and immune pneumonitis could unavoidably lead to changes in CEA levels. Komatsu et al.9 reported that CEA rose from 12.2 to 25.7 ng/mL after everolimus treatment of a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma; CEA declined to 5.9 ng/mL 2 months after discontinuation of everolimus. The authors believe that this was due to everolimus causing grand glass opacities in bilateral lungs. There is wide variation in the proportion of patients with benign lung diseases (BLD) with CEA elevations due to difference in sample size, detection methods, cutoff values and sources of BLD and up to 66.1% of patients with BLD reportedly have elevated CEA levels8,10. Therefore, it is necessary to define CEA levels in patients of different BLD. In the current study, we determined the serum CEA levels of 4,796 hospitalized patients with BLD at our tertiary care hospital.

Patients and methods

Patients

This retrospective study enrolled patients whose lung disease was confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan or X-ray and who received treatment at the Department of Respiratory Medicine or Department of Thoracic Surgery at Daping Hospital, Chongqing, China between January 2007 and December 2017. The main exclusion criteria were (1) malignancy; (2) healthy subjects; (3) incomplete clinical data.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Daping Hospital and conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki. Patient consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Daping Hospital because of the retrospective nature of the study. Patient data were anonymized in this report.

Data retrieval

We retrieved demographics including age, sex, smoking status, CEA value, and clinical data from the electronic hospital’s records system. For patients with CEA > 5 ng/mL, we obtained demographic characteristics (gender, age, and smoking status), hematological results, thyroid function, blood glucose, and liver function, radiological studies including B-ultrasound, CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and chest X-ray and medical history.

The patients with lung nodules were pathologically diagnosed by surgery, biopsy, or fiberoptic bronchoscope. If the patient showed no pathology, the medical records of one year were retrieved to confirm the disease. Malignant tumors diagnosed one year later were defined as unrelated to the tumor marker.

Serum CEA test was determined by LuminexxMAP assays and the cutoff value was set as 5 ng/mL. Nonsmoker was defined as never smoking or cessation more than 5 years.

Data extraction from literature

We searched PubMed using the search words “CEA or carcinoembryonic antigen”, “lung” for literature published between 1995 and the date of the search. We further manually searched the references in the eligible articles for inclusion as well. Articles published in English were included. We excluded studies unrelated to BLD. Articles with no information on CEA or the maximal CEA level in BLD, or with incomplete information were also excluded. Some of the maximal CEA level was estimated from the curve images.

All data were extracted independently by two investigators (MX and IY) using a standardized form. Extracted data included the name of the first author, type of BLD, total number of patients, cutoff value of CEA, the number of patients with CEA above the cutoff value and the maximum value of CEA. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third investigator (HH).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software package (version 16.0) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Measurement data were expressed as median and range. The difference among different groups and the odds ratio were analyzed by Chi square test or one-way ANOVA. Graphs were drawn using Excel software. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Daping Hospital. Patient consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Daping Hospital due to retrospective nature of study.

Results

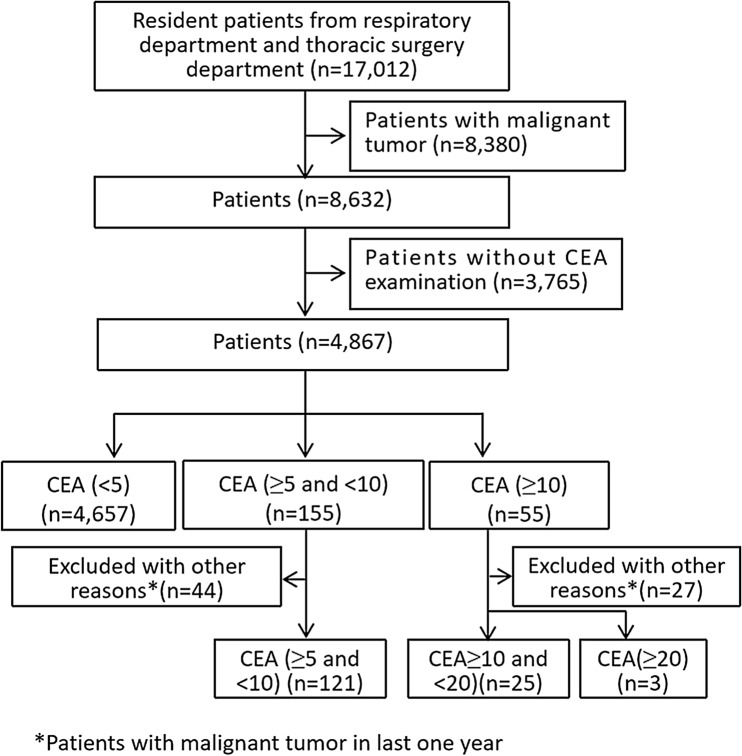

Patient screening and the distribution of benign lung diseases

The study flow chart is shown in Fig. 1. Totally 17,012 cases received treatment between January 2007 and December 2017. We excluded 8380 cancer patients. In addition, 3765 patients with no data on CEA were excluded. Totally 4867 patients met the eligibility requirements. Seventy-one patients were diagnosed with cancer during the course of follow up and were excluded from final analysis. Finally, 4796 patients were included in the final analysis, with 3249 male patients and 1547 female patients. Their median age was 58 years (range 18, 90). Pulmonary tuberculosis was the most frequent benign lung disease (1311, 27.34%), followed by COPD (1270, 26.48%) and inflammatory pseudotumor (1018, 21.23%). The distribution of other benign diseases is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The study flowchart.

Table 1.

Serum CEA contents according types of benign lung diseases.

| Diagnose | N | N of CEA > 5 mg/mL | N of CEA > 10 mg/mL | Maximum value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD | 1270 | 61 (4.80%) | 12 (0.94%) | 17.33 |

| Pneumonitis/COP | 484 | 23 (4.75%) | 3 (0.62%) | 40.12 |

| IP | 1018 | 14 (1.38%) | 1 (0.09%) | 11.22 |

| Tuberculosis | 1311 | 7 (0.53%) | 1 (0.07%) | 10.18 |

| Pulmonary abscess | 290 | 4 (1.38%) | 1 (0.35%) | 11.73 |

| Bronchiectasis | 110 | 5 (4.54%) | 0 | 8.7 |

| Pneumothorax | 62 | 3 (4.83%) | 0 | 6.61 |

| Asthma | 46 | 5 (10.87%) | 2 (4.35%) | 10.04 |

| ILD/CTD-ILD | 115 | 19 (16.52%) | 4 (3.48%) | 24.25 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 63 | 2 (3.17%) | 1 (1.59%) | 11.78 |

| PAP | 27 | 6 (22.22%) | 3 (11.11%) | 28.02 |

| Total | 4796 | 149 (3.11%) | 28 (0.58%) | – |

COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ILD Interstitial lung disease, CTD-ILD Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, PAP Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, IP Inflammatory pseudotumor, COP cryptogenic organizing pneumonia.

In this study, benign lung nodules mainly included inflammatory pseudotumor (n = 1018) and tuberculoma (n = 192). Most of them were confirmed by pathology. Only 3.1% (n = 32) of inflammatory pseudotumor and 9.9% (n = 19) of tuberculoma were diagnosed by patients’ imaging, clinical symptom and laboratory examination. All the lung nodules without pathology have been confirmed by one-year follow-up.

Patient serum CEA contents

The mean serum CEA content was 1.51 ± 1.12 ng/mL (median, 1.39; range 0.02, 40.12). CEA was > 5 ng/ mL in 149 (3.11%) patients, > 10 ng/mL in 28 (0.58%) patients and > 20 ng/mL in 3 (0.06%) patients (Table 1). More males (67.78%) had CEA > 5 ng/mL than females (32.21%). Patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis had the highest positive CEA rate (22.22%), followed by interstitial lung disease (ILD) [including connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD)] (16.52%) and asthma (10.87%). Among benign diseases with more than 1000 cases, pulmonary tuberculosis patients had the lowest positive rate (0.53%, 7/1311) while COPD patients had the highest CEA positive rate (4.8%, 61/1270) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 online).

The highest CEA level in this study was 40.12 ng/mL. This patient had cough and intermittent hemoptysis for one year, and two examinations within 2 months before surgery showed CEA values of 36.1 ng/mL and 40.12 ng/mL, respectively, with a concurrent significant rise in CA125. Two preoperative CT scans revealed obstructive inflammation of the right lower lobe. Bronchofibroscopy suggested mucosal hyperemia in bronchi of various lobes of the right lung, and the lumen became narrowed due to mucosal swelling, especially in the lower right lung. Biopsy suggested chronic mucositis. Finally, wedge resection of the lower lobe of the right lung was carried out and postoperative pathology showed cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), likely due to aspiration-induced coughing a year ago. CEA levels returned to normal after surgery.

Correlates of CEA elevations

When the cutoff value of CEA was set as 5 ng/mL, age > 65 years were 2.69 (95% CI 1.94–3.73, p < 0.001) times more likely to have CEA elevations than patients aged < 65 years (Table 3 and Supplementary data). However, gender (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.71–1.42; p = 0.991) and smoking history (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.80–1.54; p = 0.535) were not significant risk factors for CEA elevations (Table 2).

Table 3.

Summary of CEA levels in benign lung diseases reported in the literature.

| Author | N | Cutoff (ng/mL) | N of CEA > cutoff | Maximum value | Type of disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schneider et al.10 | 106 | 6.4 | 0 | 6.4 | Pneumonitis and COPD |

| Sharma et al.11 | 18 | 5 | 1 (5.56%) | 6.8 | Tuberculosis |

| Wang et al.12 | 87 | 9.8 | 2 (2.3%) | 10.8 | Tuberculosis; pulmonary infection; COPD |

| Kulpa et al.13 | 96 | 4 | 5 (5.2%) | 9.5 | Sarcoidosis; tuberculosis; fibrosis, asthma; hamartoma; noncancerous tumors; pneumonitis |

| Nisman et al.14 | 85 | 5 | 6 (7.05%) | 10a | Infectious lung diseases; diffuse noninfectious lung diseases; COPD |

| Song et al.15 | 124 | 5 | 7 (5.65%) | 8.93 | Tuberculosis; inflammatory pseudotumor; other benign tumors |

| Beržinec et al.16 | 10 | 4.61 | 1 (10%) | 6.37 | Benign respiratory tract diseases |

| Gruber et al.17 | 318 | 12 | 10 (3.14%) | 20a | Tuberculosis; pneumonitis; pleural effusion; sarcoidosis; fibrosis; COPD; Benign lung tumors; others |

| Fahim et al.18 | 41 | 5 | 21 (51%) | 26a | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| Total | 885 | 53 (5.99%) |

COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

aApproximate value.

Table 2.

Risk factors of CEA abnormalities.

| CEA (< 5 ng/mL) | CEA (≥ 5 ng/mL) | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| < 65 | 3298 | 71 | 2.686 | 1.935–3.727 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 65 | 1349 | 78 | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 3148 | 101 | 1.002 | 0.707–1.421 | 0.991 |

| Female | 1499 | 48 | |||

| Smoking status | |||||

| Smoker | 2064 | 70 | 1.109 | 0.800–1.538 | 0.535 |

| Nonsmoker | 2583 | 79 | |||

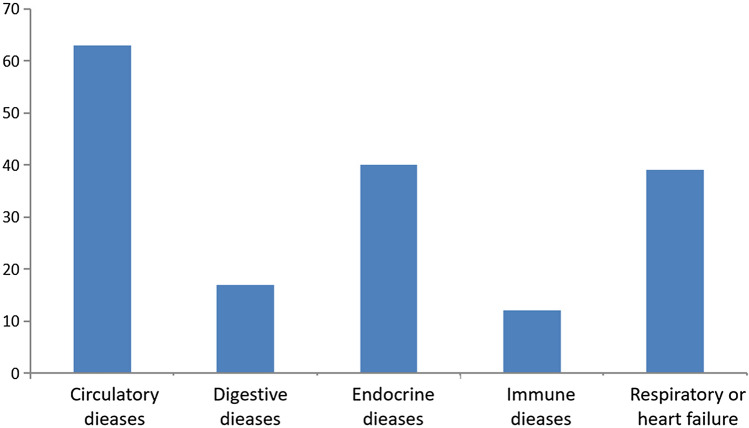

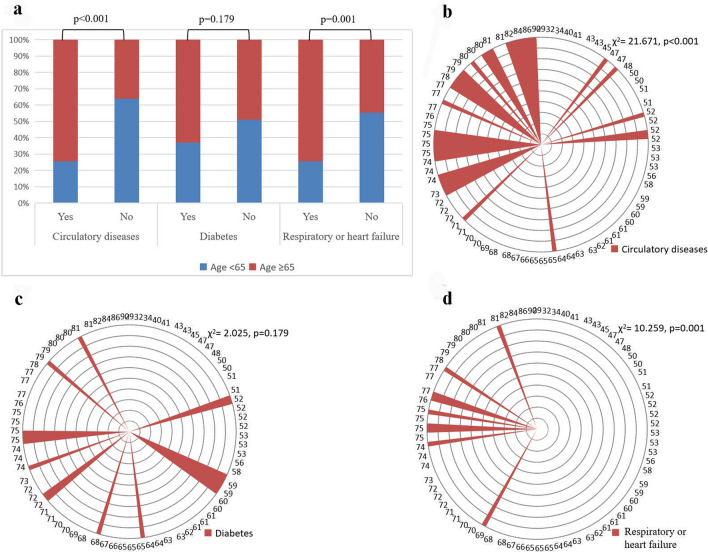

As the CEA elevations may be affected by concomitant diseases, further study was conducted on the concomitant diseases of the patients with CEA elevations. The majority of these patients had multiple underlying diseases, mainly diseases of the circulatory system (42.28% [63/149]), endocrine diseases (26.85% [40/149]), and respiratory or heart failure (24.16% [36/149]. In endocrine diseases, 87.5% (35/40) of patients had diabetes. Diseases of the circulatory system and respiratory or heart failure were highly correlated with age (χ2 = 21.671, p < 0.001; χ2 = 10.259, p = 0.001) while diabetes was not correlated with age. Immune-related diseases and diseases of the digestive system were less common in BLD (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Concomitant diseases in patients with CEA levels above 5 ng/mL.

Figure 3.

Relationship between concomitant diseases and age. (a) Relationship between concomitant diseases and age; (b) Relationship between age and diseases of the circulatory system; (c) Relationship between age and diabetes; (d) Relationship between age and respiratory or heart failure.

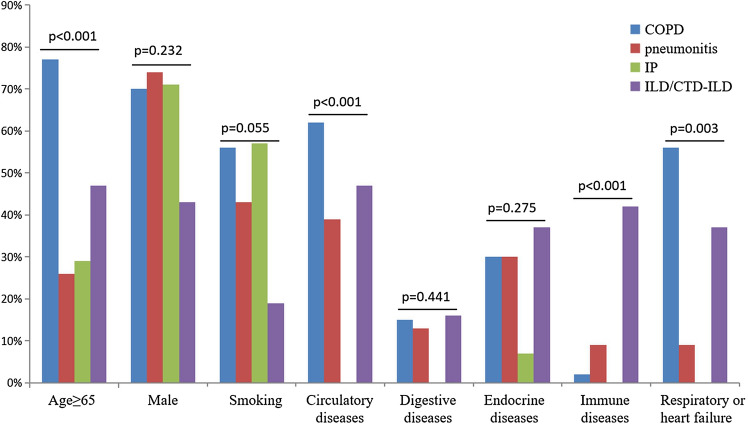

Among patients with COPD, pneumonitis, inflammatory pseudotumor and interstitial lung disease, which had more than 10 cases with CEA elevations, univariate analysis of variance showed no statistical difference in CEA levels (F = 0.925, p = 0.426). Age and comorbid diseases of the circulatory system, immune disease and respiratory or cardiac failure were significantly different among the four groups (χ2 = 24.212, p < 0.001; χ2 = 18.648, p < 0.001; χ2 = 2 8.638, p < 0.001; χ2 = 14.261, p = 0.003). Sex, smoking status, and endocrine diseases including diabetes (χ2 = 2.897, p = 0.408) and diseases of the digestive system showed no statistical difference among the four groups. COPD patients were older (median age = 74 years, ≥ 65 years = 77%) and had a higher rate of diseases of the circulatory system (62.30%) and cardiorespiratory failure (39.34%). ILD patients had a higher proportion of comorbid immune disease (42.11%) and cardiorespiratory failure (36.84%). Inflammatory pseudotumor patients had few comorbidities (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Characteristics of CEA elevations in four types of benign lung disease. COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IP Inflammatory pseudotumor, CTD-ILD Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, ILD Interstitial lung disease.

CEA levels of benign lung diseases in the literature

Our PubMed search found 9 eligible studies from 4191 papers10–18, including 885 cases of BLD. The sample size varied between 10 and 318. The CEA cutoff value ranged between 4 ng/mL and 12 ng/mL in these studies and the positive rate between 0 and 51%. Different studies included different types of benign diseases, but were dominated by pulmonary tuberculosis, COPD, pneumonitis and benign lung tumors in these studies. There were 53 positive cases, and a mean positive rate of 5.99%. Only two cases had CEA above 20 ng/mL (Table 3).

Discussion

CEA is a glycoprotein involved in cell attachment and is produced by intestinal epithelia during fetal development and production is ceased upon birth. CEA, which is detected in very small amounts in the serum in healthy individuals, is used clinically as a serological tumor biomarker, especially colorectal carcinoma, and other cancers that are of adenocarcinoma type including gastric cancer and lung cancer. In addition, CEA levels are also elevated in certain benign diseases, including nonulcerative colitis, pancreatitis, liver cirrhosis, ascites, metabolic abnormalities (diabetes, hypothyroidism etc.), peptic ulcer and pulmonary fibrosis19. Furthermore, smoking and advanced age also lead to CEA elevations20. Hao et al.21 examined CEA in 70,993 patients with 49 types of diseases and found that the median CEA value was significantly different in 42 types of diseases versus healthy subjects, among them, in the descending order, pulmonary fibrosis, pancreatic cancer, uremia, COPD, colorectal carcinoma, Alzheimer’s disease and lung cancer. The study indicated that pulmonary fibrosis (median 4.2 ng/ mL) and COPD (median 3.0 ng/mL) could easily lead to CEA elevations, which in some cases could exceed the median CEA of certain tumors. Literature has shown that 66.1% of IPF patients who were candidates for lung transplant had CEA elevations (cutoff 4.05 ng/mL)8. It has been shown that CEA elevation is closely related with severity of lung diseases8. Consistently, our current study showed that a greater proportion of patients with COPD and ILD had elevated CEA levels than patients with other types of BLD, and a higher proportion of patients with elevated CEA levels had cardiopulmonary failure. The current study also revealed that very few pulmonary tuberculosis patients had CEA elevations while pulmonary alveolar proteinosis had the highest positive rate among BLD. In addition, COPD patients were older and a higher rate of diseases of the circulatory system and cardiorespiratory failure, which may at least partially explain its relatively high CEA positive rate. Moreover, this study found that 23.48% patients with elevated CEA levels had diabetes. Diabetes exhibits no difference among different lung diseases and didn’t correlate with age of patients, indicating that diabetes might be a very important risk of CEA elevation. However, diabetes itself related to many BLD, such as IPF and COPD, which have been reported by literature22. Only 3.11% of our benign lung disease patients had elevated CEA levels, only 0.58% patients had CEA > 10 ng/mL and only 3 (0.06%) patients had CEA above 20 ng/mL. Limited data from currently available literature in PubMed also indicated that only three patients (including one case reprort23) had CEA > 20 ng/mL. Therefore, CEA in patients with BLD infrequently exceed 10 ng/mL and rarely exceeds 20 ng/mL.

Previous studies indicate that smoking is a determinant of CEA levels. Alexander et al.20 measured serum CEA levels in 276 healthy volunteers, including 154 smokers and 122 nonsmokers using Hansen-Z-gel technique, and showed the mean CEA level (2.7 ng/mL) in smokers was markedly higher than that of nonsmokers (1.9 ng/mL) (p < 0.001). Fukuda et al.24 determined CEA levels in 1341 subjects. In male subjects, the mean CEA level in smokers (3.11 ± 1.8 ng/mL) was significantly higher than that of nonsmokers (2.14 ± 1.8 ng/mL; p < 0.01) while in females, there was no difference in CEA levels between smokers (2.11 ± 0.91 ng/mL) and nonsmokers (1.87 ± 2.13 ng/mL). In the current study, for BLD patients, using 5 ng/mL as the cutoff and chi-square test, we found no effect of smoking on CEA positive rate, indicating that smoking may only have insignificant effect on CEA levels.

The mechanisms behind CEA elevated levels in benign lung disease is poorly understood until now. It has been reported that Kupffer cells and alveolar macrophages can endocytose CEA through their surface receptors25,26, and many factors may cause the endocytosis dysfunction of these cells. Tanaka et al.23 reported a 44-year-old man with diagnosis of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. CEA level was markedly elevated in his serum (50.6 ng/mL). It was suggested that type II alveolar epithelial cells were those which produced and secreted CEA into the alveoli, and that the dysfunction of alveolar macrophages was secondary to the overingestion of the proteinaceous material in the alveoli. In addition, it has been reported that alcohol can also damage the endocytosis of CEA by Kupffer cells27.

Certainly, this study is a retrospective study and cannot exhaust all the causes in search of determinants of CEA elevations and therefore cannot fully exclude other possible contributors to CEA elevations, which may impact on the accuracy of this study. In addition, though this is a large sample study, some BLD have a small size because of their low prevalence, which may affect the accuracy of the results. Of course, the current study population was from single center in China and the study findings may not be applicable to other ethnicities. More accurate data depends on global prospective multicenter study with a large sample size.

In summary, for lung disease patients, if CEA levels rise, we should carry out comprehensive analysis of types of lung diseases, age of patients, and comorbid illnesses. For lung cancer patients, CEA elevation in the course of treatment should prompt clinicians to consider the extent of CEA elevation, apart from disease progression. Drug-induced (including chemical drugs, targeted drugs, and immunotherapeutic agents) pneumonitis, interstitial lung disease, radiation pneumonitis or pulmonary fibrosis, and concomitant respiratory failure should be excluded. Meanwhile, for patients with confirmed lung occupying lesions, if CEA exceeds 20 ng/mL, malignancy should be highly suspected; this will provide certain evidence for clinical diagnosis when biopsy is not feasible.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ILD

Interstitial lung disease

- CTD-ILD

Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease

- PAP

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

- IP

Inflammatory pseudotumor

- COP

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

- BLD

Benign lung disease

- IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Author contributions

Y.Y., X.M. and H.H. and undertook most of the work, they should be regarded as co-first author. G.K., L.Y., J.X. and K.X. participated in data collection and analysis. Y.X. designed the study. All authors have contributed to the last version of the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Key projects of Chongqing Health and Family Planning Commission (to Xueqin Yang, 2019ZDXM011).

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yi Yang, Mingfang Xu, and Huan Huang.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-98513-8.

References

- 1.Grunnet M, Sorensen JB. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as tumor marker in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;762:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He G, Jiang Z, Xue S, Sun X, Wang W. Expression of LDH and CEA in serum in the process of targeted therapy of lung adenocarcinoma and the association between them and prognosis. Oncol. Lett. 2019;17:4550–4556. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrieta O, Villarreal-Garza C, Martínez-Barrera L, Morales M, Dorantes-Gallareta Y, Peña-Curiel O, Contreras-Reyes S, et al. Usefulness of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in evaluating response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced non small-cell lung cancer: A prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:254. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamoto T, Nakamura T, Ikeda J. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen as a predictive marker for sensitivity to gefitinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2005;41:1286–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao XC, Wei CH, Zhang RG, Cai Q, He Y, Tong F, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT SUVmax and serum CEA levels as predictors for EGFR mutation state in Chinese patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2020;20:61. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo YS, Zheng MY, Huang MF, Miao CC, Yang LH, Huang TW, et al. Association of divergent carcinoembryonic antigen patterns and lung cancer progression. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:2066. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruibal MA. CEA serum levels in non-neoplastic disease. Int. J. Biol. Markers. 1992;7:160–166. doi: 10.1177/172460089200700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu WS, Lee JG, Paik HC, Kim SJ, Lee S, Kim SY, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen predicts waitlist mortality in lung transplant candidates with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018;54:847–852. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezy170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komatsu H, Izumi N, Tsukioka T, Toda M, Hara K, Miyamoto H, et al. Elevation of serum carcinoembryonic antigen concentration caused by everolimus-induced lung injury: A case report. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018;24:151–153. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.17-00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider J, Philipp M, Velcovsky HG, Morr H, Katz N. Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (ProGRP), neuron specific enolase (NSE), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cytokeratin 19-fragments (CYFRA 21–1) in patients with lung cancer in comparison to other lung diseases. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:885–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma SK, Bhat S, Chandel V, Sharma M, Sharma P, Gupta S, et al. Diagnostic utility of serum and pleural fluid carcinoembryonic antigen, and cytokeratin 19 fragments in patients with effusion from nonsmall cell lung cancer. J. Carcinog. 2015;14:7. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.170662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang B, He YJ, Tian YX, Yang RN, Zhu YR, Qiu H. Clinical utility of haptoglobin in combination with CEA, NSE and CYFRA21-1 for diagnosis of lung cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014;15:9611–9614. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.22.9611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulpa J, Wójcik E, Reinfuss M, Kołodziejski L. Carcinoembryonic antigen, squamous cell carcinoma antigen, CYFRA 21–1, and neuron-specific enolase in squamous cell lung cancer patients. Clin. Chem. 2002;48:1931–1937. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/48.11.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nisman B, Lafair J, Heching N, Lyass O, Baras M, Peretz T, et al. Evaluation of tissue polypeptide specific antigen, CYFRA 21–1, and carcinoembryonic antigen in nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: Does the combined use of cytokeratin markers give any additional information? Cancer. 1998;82:1850–1859. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1850::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song WA, Liu X, Tian XD, Wang W, Liang CY, Zhang T, et al. Utility of squamous cell carcinoma antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, Cyfra 21–1 and neuron specific enolase in lung cancer diagnosis: A prospective study from China. Chin. Med. J. 2011;124:3244–3248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berzinec P, Zuffová H, Letkovicová M, Arpásová M. Serum tumor marker CYFRA 21–1 in the diagnostics of squamous cell lung cancer-comparison with CEA. Neoplasma. 1996;43:159–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber C, Hatz R, Reinmiedl J, Nagel D, Stieber P. CEA, CYFRA 21–1, NSE, and ProGRP in the diagnosis of lung cancer: a multivariate approach. J. Lab. Med. 2008;32:361–371. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fahim A, Crooks MG, Wilmot R, Campbell AP, Morice AH, Hart SP. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen correlates with severity of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2012;17:1247–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chevinsky AH. CEA in tumors of other than colorectal origin. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 1991;7:162–166. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980070309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander JC, Silverman NA, Chretien PB. Effect of age and cigarette smoking on carcinoembryonic antigen levels. JAMA. 1976;235:1975–1979. doi: 10.1001/jama.1976.03260440027017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao C, Zhang G, Zhang L. Serum CEA levels in 49 different types of cancer and noncancer diseases. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019;162:213–227. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khateeb J, Fuchs E, Khamaisi M. Diabetes and lung disease: A neglected relationship. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2019;15:1–15. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2019.15.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka F, Nakamura M, Nakashima H, Suga M, Sugimoto M, Ando M, et al. A case of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis accompanied with the elevation of CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;27:968–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukuda I, Yamakado M, Kiyose H. Influence of smoking on serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels in subjects who underwent multiphasic health testing and services. J. Med. Syst. 1998;22:89–93. doi: 10.1023/A:1022643102208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas P, Zamcheck N. Role of the liver in clearance and excretion of circulating carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) Dig. Dis. Sci. 1983;28:216–224. doi: 10.1007/BF01295116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toth CA, Rapoza A, Zamcheck N, Steele G, Thomas P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of carcinoembryonic antigen by rat alveolar macrophages in vitro. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1989;45:370–376. doi: 10.1002/jlb.45.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohr AM, Gould JJ, Kubik JL, Talmon GA, Casey CA, Thomas P, et al. Enhanced colorectal cancer metastases in the alcohol-injured liver. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2017;34:171–184. doi: 10.1007/s10585-017-9838-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.