Abstract

Transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution with a suitably pre-stored leaving group in the substrate is widely used in organic synthesis. In contrast, the enantioselective allylic C(sp3)-H functionalization is more straightforward but far less explored. Here we report a catalytic protocol for the long-standing challenging enantioselective allylic C(sp3)-H functionalization. Through palladium hydride-catalyzed chain-walking and allylic substitution, allylic C-H functionalization of a wide range of acyclic nonconjugated dienes is achieved in high yields (up to 93% yield), high enantioselectivities (up to 98:2 er), and with 100% atom efficiency. Exploring the reactivity of substrates with varying pKa values uncovers a reasonable scope of nucleophiles and potential factors controlling the reaction. A set of efficient downstream transformations to enantiopure skeletons showcase the practical value of the methodology. Mechanistic experiments corroborate the PdH-catalyzed asymmetric migratory allylic substitution process.

Subject terms: Asymmetric catalysis, Catalytic mechanisms, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Alkene isomerizations and asymmetric C–H functionalizations have been independently studied, but their combination in one protocol is uncommon. Here the authors show a palladium-catalyzed method to iteratively “walk” a terminal alkene along a carbon chain to a position next to styrenes where a soft nucleophile is added asymmetrically.

Introduction

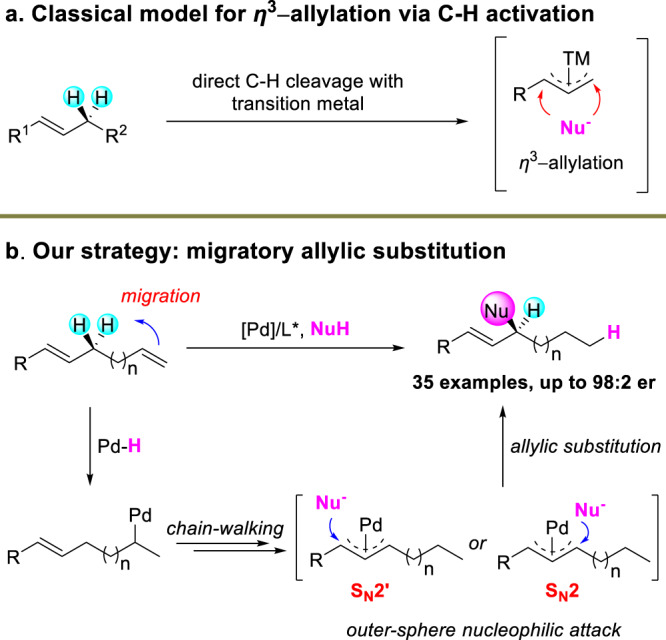

Transition metal-catalyzed enantioselective allylic substitution has emerged as one of the most useful and reliable transformations for precise stereo- and regiocontrol over a target compound in organic synthesis1–6. The constructed carbon−carbon or carbon-heteroatom stereocenter vicinal to a C = C bond can enrich the downstream derivatizations. Diverse transition metals like Pd, Ir, Rh, Ru, Cu, Ni et al have witnessed extensive studies and applications in asymmetric ƞ3-allylic substitution1–6. In general, an alkene prefunctionalized with an allylic leaving group undergoes oxidative addition to a transition metal to furnish a thermodynamically stable ƞ3-π-allyl metal species. Subsequent outer-sphere nucleophilic attack provides the allylation product stereo- and regioselectively. Alternative precursors, such as allenes, alkynes, and 1,3-dienes, for stereoselective allylations have also achieved considerable progress7,8.

In contrast, the corresponding allylic C−H functionalization ought to be more straightforward and economic but is far less developed9,10. In general, the key ƞ3-π-allyl metal intermediate is generated through direct allylic C−H cleavage (Fig. 1a)10. Elegant studies from Rainey11, Trost12,13, Gong14–19 and White20,21 groups et al. have realized the C−H functionalization of the allylic carbon center that usually requires further activation by another vicinal sp2 carbon or heteroatom unit. A few studies have been performed on unactivated allylic C−H bond but generally with moderate enantioselectivities22–25. Therefore, efficient strategies are still highly desired for enantioselective allylic C−H functionalization, especially for functionalization with inert allylic C−H bonds.

Fig. 1. Transition metal-catalyzed allylic C−H substitution.

a Classical model for enantioselective transition metal-catalyzed allylic C−H substitution. b Our strategy: metal migration triggers allylic C(sp3)-H functionalization. NuH, nucleophile.

Metal walking26–35 along an aliphatic chain via iterative β-hydride elimination and alkene hydrometallation has proven to be very effective in realizing activation at a remote C−H bond36–41. Recently, Wu42 and Zhou43 developed enantioselective tandem Heck/Tsuji−Trost reaction of 1,4-cyclohexadienes to prepare difunctionalized cyclohexenes42–49. In 2020, Fang et al. reported a Ni-catalyzed asymmetric hydrocyanation of skipped dienes, providing allyl nitriles via inner-sphere reductive elimination33. Inspired by these elegant studies, we envisioned that with a remote olefin unit prestored in a target allyl compound, the combination of metal hydride-catalyzed50,51 alkene migration to indirectly realize the allylic C−H activation followed by ƞ3-allylation might provide a conceptually different strategy to the challenging allylic C−H functionalization42–49. Specifically, a terminal olefin first inserted into a palladium hydride catalyst52–66 generated facilely in situ and was then transferred to a remote target allylic carbon center via metal walking. The subsequent outer-sphere nucleophilic attack of the resulting ƞ3-allyl palladium species would yield an allylic C−H functionalization product (Fig. 1b). However, this 100% atom-economic C−H allylation process is not straightforward. The merger of stereoselective PdH-catalyzed olefin migration and ƞ3-allylation is unknown, presumably due to issues from the compatibility of two different processes and the stereoselectivity control inside, especially along a flexible acyclic olefin chain.

Here, we show that the merger of PdH-catalyzed chain-walking and ƞ3-allylation serves as an efficient route to the stereoselective activation of the inert allylic C(sp3)−H bond. A series of flexible acyclic nonconjugated dienes undergo the C(sp3)−H allylation in high yields and enantioselectivities (up to 93% yield, generally 90−96% ee) and 100% atom-efficiency. Mechanistic studies further provide evidence for the designed migratory allylation strategy.

Results

Investigation of reaction conditions

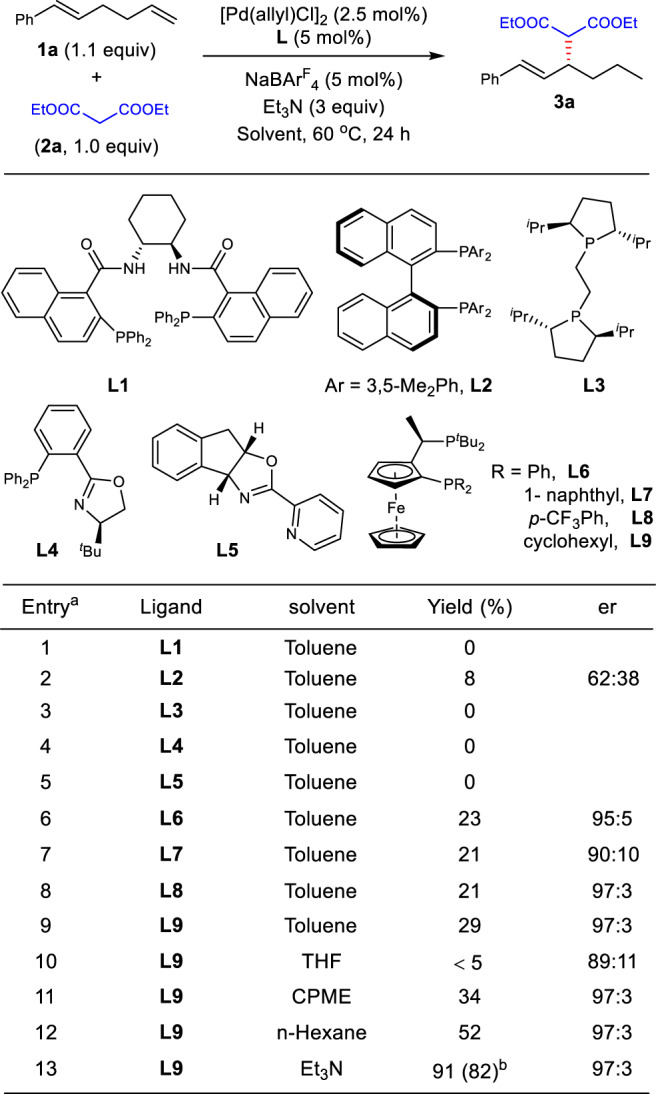

We initiated the migratory allylic functionalization by studying reactions with an acyclic non-conjugated diene 1a as the pre-electrophile, diethyl malonate 2a as the pronucleophile, and Et3N as the base with a palladium catalyst (Fig. 2). A group of chiral ligands were first evaluated for their potential to facilitate both the chain walking and allylic substitution. Trost ligand L1 which was effective in Pd-catalyzed allylation, failed to furnish the target product 3a (entry 1)67. Trace amounts of 3a were observed with bisphosphine ligand L2 in low enantioselectivity, and L3 did not provide any product (entries 2−3). Because oxazoline-type ligands have been widely adopted in Pd-catalyzed chain-walking reactions36–41, we turned to L4 and L5 for the possibility of migratory allylic substitution. However, none of them led to the desired allylation product 3a (entries 4−5). Then a set of JosiPhos-type chiral ligands were further evaluated due to their previous application in Pd-catalyzed asymmetric hydrofunctionalization of conjugated dienes (entries 6−9)58,59. Fortunately, around 20% yield of 3a was observed for all cases, and the enantioselectivities were achieved up to 97:3. The reaction yield was finally raised to 82% when Et3N was used as both the base and solvent, though many other solvents also benefited the yield (entries 10−13). Thus, the optimal condition for migratory allylic functionalization was identified as the combination of the skipped diene 1a (1.1 equiv), nucleophile 2a (1.0 equiv), [Pd(allyl)Cl]2 (2.5 mol%), L9 (5 mol%) and NaBArF4 (5 mol%) in Et3N at 60 oC for 24 h.

Fig. 2. Evaluation of reaction conditions for the migratory allylic substitution.

aThe reactions were run with 2a (0.2 mmol), NaBArF4 (ArF = 3,5-(CF3)2Ph, 5 mol%) in solvent (0.2 mL). Yields were determined by crude 1H NMR. Er values were determined by chiral HPLC. THF, tetrahydrofuran. CPME, cyclopentyl methyl ether. bIsolated yield.

Substrate scope

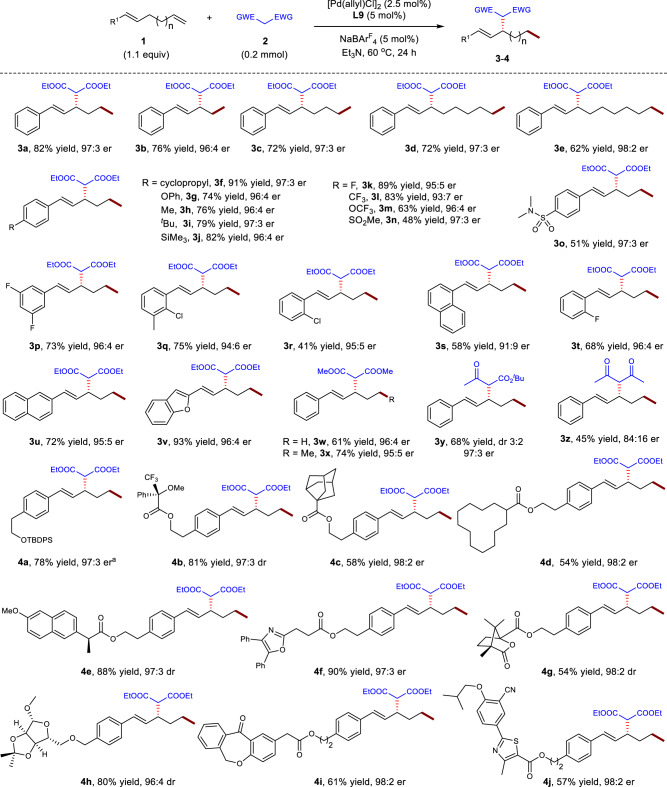

The scope of substituted nonconjugated diene electrophiles was first checked and the results are summarized in Fig. 3. Skipped dienes with interval methylene chains of different lengths had no discernible influence on the reaction yield and enantioselectivity (3a−3e). For example, flexible 1,9-diene as the electrophile delivered C(sp3)−H allylation product 3e in 62% yield and 98:2 er. Aryl units with diverse functional groups, such as alkyl, phenyloxy, strained cyclopropyl, silyl, Cl, CF3, CF3O, and OTBDPS, among others, in nonconjugated diene substrates underwent C(sp3)−H functionalization in 41−91% yield and 91:9−97:3 er (3f−3m, 3p−3u, 4a). Aryl-substituted dienes containing strong electron-withdrawing groups, such as sulfonyl or sulfamoyl units, provided the products in moderate yields but with high enantioselectivities (3n, 3o). The heteroaryl-tethered acyclic diene 1v was also suitable for the C(sp3)−H functionalization reaction, producing product 3v in 93% yield and 96:4 er.

Fig. 3. Scope of the substrates that undergo migratory allylic substitution.

The reactions were run with 1 (0.22 mmol), 2 (0.2 mmol), [Pd(allyl)Cl]2 (2.5 mol%), L9 (5 mol%), NaBArF4 (5 mol%) in Et3N (0.2 mL) at 60 oC for 24 h. EWG, electron-withdrawing group. aThe er value was determined by the HPLC analysis of the desilyl derivative of 4a.

Diverse dicarbonyl derivatives were subsequently tested for migratory allylic functionalization (3w−3z). Dimethyl malonate 2b coupled smoothly with different nonconjugated dienes in good yields and high enantioselectivities without regioselectivity issue60 (3w, 3x). α-Ketoester 2c was found to be an effective nucleophile, delivering 3y in 68% yield and 97:3 er, albeit with low diastereoselectivity because of the facile epimerization of the α-carbon center of the dicarbonyl unit. 1,3-Dione 2d with a lower pKa showed moderate reactivity and yielded allylation product 3z in 84:16 er, suggesting that the migratory allylation might be suitable for nucleophiles with a variety of pKa57.

The utility and robustness of the present protocol were also demonstrated by conducting C(sp3)−H functionalization with a series of dienes derived from complex molecules. Dienes tethered to drugs, such as naproxen, oxaprozin, isoxepac, and febuxostat, efficiently underwent the migratory allylation process to furnish the corresponding products in 57−90% yield with 97:3−98:2 er (4e, 4f, 4i, 4j). Electrophiles bearing a Mosher ester, bridged- or macrocycles, camphanic acid, or ribofuranose derivatives reacted in moderate to good yields with high enantioselectivities (4b−4d, 4g−4h). Notably, all the aforementioned cases underwent migratory allylation with exclusive regioselectivity at the target allylic carbon center. However, tertiary nucleophiles and a couple of other substrates turned out to be ineffective for this transformation (see Supplementary Methods for details).

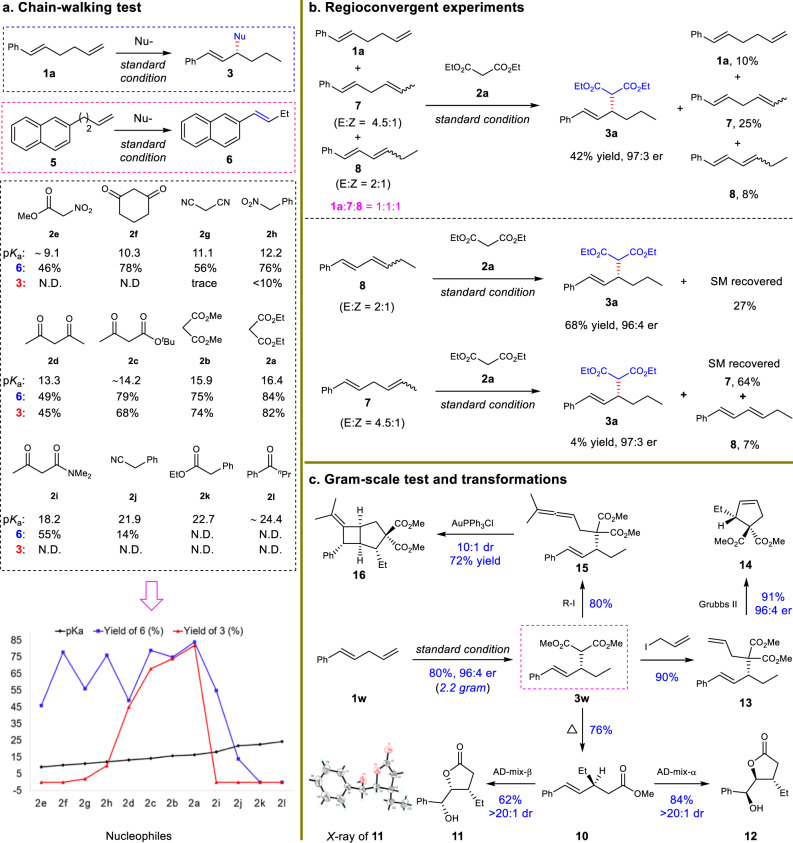

To uncover the pKa range of nucleophiles and the factors controlling reactivity, a series of nucleophiles with pKa ranging from 9 to 24 were evaluated for migratory functionalization reactions (Fig. 4a). The secondary carbon nucleophiles were chosen and evaluated in order to exclude the steric hindrance as a potential interference factor. As the present protocol contained two processes, i.e., chain walking and allylic substitution, alkene 5, which could only undergo chain walking, was adopted to test the walking potential of a chosen nucleophile under standard conditions. Using a nucleophile (2e−2h) with a pKa < 13 resulted in olefin 5 smoothly undergoing chain-walking to produce 6 in 46−78% yield, but little allylation was observed. By contrast, gradually increasing the pKa of the nucleophiles from 18 to 24 (2i−2k), resulted in almost no chain-walking or allylation. Therefore, nucleophiles with pKa between 13 and 18 appear to be suitable for target migratory allylation (2a−2d). Our data suggest that the migratory allylation for nucleophiles with pKa < 13 might be limited by insufficient nucleophilicity, whereas that for nucleophiles with pKa > 18 does not lead to chain-walking because of insufficient acidity to generate the palladium hydride catalyst.

Fig. 4. Scope of nucleophiles and applications.

a Chain-walking test of nucleophiles. The blue color of the curve represents the yield of compound 6. The red color of the curve represents the yield of compound 3. The black color of the curve represents the pKa value of corresponding nucleophiles used. pKa values in DMSO were shown. N.D. not detected. b Regioconvergent experiments. c Gram-scale test and synthetic application.

The mixtures of stereoisomers and regioisomers of skipped dienes underwent regioconvergent migratory allylation in moderate yield and high enantioselectivity (Fig. 4b). To uncover the factor leading to the decreased reactivity, diene 7 or 8 was used as substrate individually under standard condition. The conjugated diene 8 underwent hydrofunctionalization smoothly, giving 3a in good yield and high er, though 27% of 8 remained unreacted. In contrast, the internal skipped diene 7 showed very low reactivity, providing 3a in only 4% yield but with high er. We proposed that the coordination of palladium catalyst with the diene substrate might be a crucial factor controlling the results. It should be easier for palladium catalyst to initiate the reaction by coordinating with diene substrate 1a bearing a terminal olefin than 7 and 8 with sterically bulky internal olefin units. The higher reactivity of 8 than that of 7 was possibly resulted from the quick consumption of the stable π-allyl-Pd intermediate from the migratory insertion of a conjugated diene with Pd−H catalyst.

Transformations

The synthetic value of the migratory allylation was highlighted by a gram-scale test and a series of downstream transformations (Fig. 4c). A total of 2.2 gram of compound 3w were obtained in high yield and enantioselectivity under standard conditions. This compound was then converted to a set of important skeletons in short steps. A combination of decarboxylation and oxidation was used to efficiently prepare γ-lactones 11 and 12 with multiple stereogenic centers, as demonstrated by X-ray crystal analysis. Enantiopure cyclopentene 14 was easily constructed through a metathesis reaction. Moreover, Au(I)-catalyzed [2 + 2] cycloaddition68 enabled the enantioselective construction of complex bicyclo-[3.2.0] motif 16, which exists widely in biologically active molecules69.

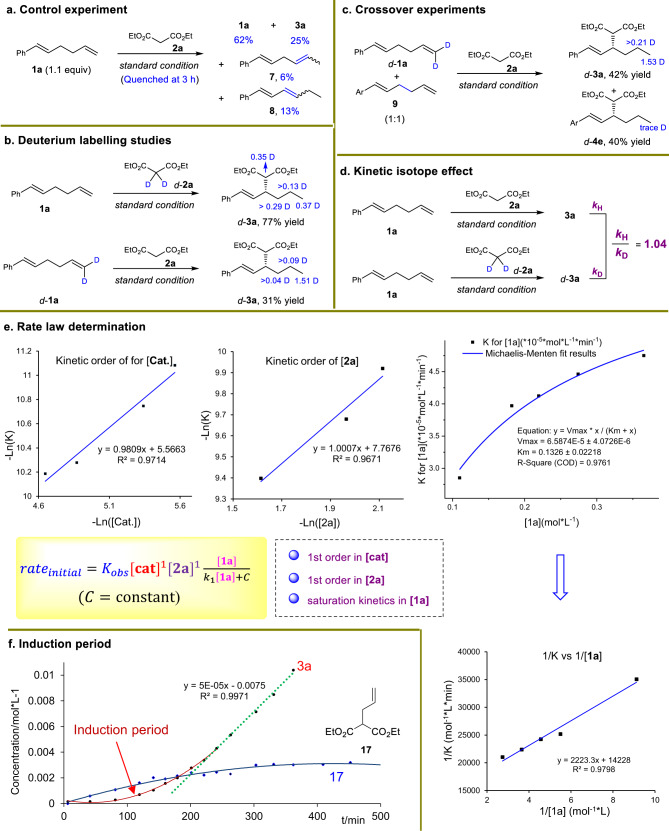

Mechanistic studies

A set of mechanistic studies were conducted to further elucidate the mechanism of the present protocol (Fig. 5). Quenching the model reaction after only 3 h produced compounds 7 and 8 via alkene migration in 6% and 13% yields, respectively, along with a 25% yield of product 3a (Fig. 5a). This fact supports that chain-walking is involved in the reaction, which is further corroborated by the results of deuteration studies showing D labeling of product d-3a at multiple carbon centers (Fig. 5b). Moreover, a crossover experiment using deuterated d-1a and non-deuterated diene 9 as competing electrophiles led to the detection of d-4e (Fig. 5c). The transfer of D atoms from d-1a to d-4e suggests that the PdH catalyst might dissociate from the ligated diene substrate throughout the chain walking process. Considering the very trace deuteration observed in d-4e, we deduced that PdH dissociation from the diene substrate might be a challenging and negligible process38.

Fig. 5. Mechanistic studies.

a Control experiments to uncover the reaction intermediates. b Deuterium labeling studies show the involvement of olefin migration. c Crossover experiments. d Kinetic isotope effect. e Rate law determination to elucidate the rate-determining step. f Initial kinetic studies of 3a and 17 for induction period determination.

Kinetic isotope effect (KIE) was determined to be 1.04, implying that the PdH formation or chain walking process involving hydrogen bond formation or breaking might not be the rate-determining step (Fig. 5d). Further kinetic studies uncovered that the migratory allylation reaction was first order in both [cat] and [2a] (Fig. 5e). However, the kinetic data of diene 1a did not suggest a simple first or zero reaction order, but a saturation kinetics, fitting Michaelis−Menten dynamic model which is commonly used to describe enzymatic reaction70. This observation was further supported by a linear relationship between rate−1 and [1a]−1 (Fig. 5e). In order to corroborate the aforementioned facts, we hypothesized the final allylic substitution was the rate-determining step, and deduced the corresponding initial rate equation (see Supplementary Methods for details). This rate law was consistent with all of the observed kinetic data. Thus, the rate-determining step in the catalytic cycle was determined as the allylic substitution.

In the kinetic studies, an obvious induction period was detected. To elucidate the origin of the induction period, compound 17 from the reaction of nucleophile 2a with [Pd(allyl)Cl]2 was identified (Fig. 5f). The corresponding initial reaction profile of 17 and product 3a clearly showed that the yield of 17 increased along with the slow generation of 3a at the beginning of the reaction. When 17 reached close to the highest 4−5% yield, the reaction rate for 3a arrived at an obviously higher level and maintained stable. Therefore, the induction period derived from the slow formation of active Pd(0) catalyst via off-cycle allylation.

Proposed mechanism

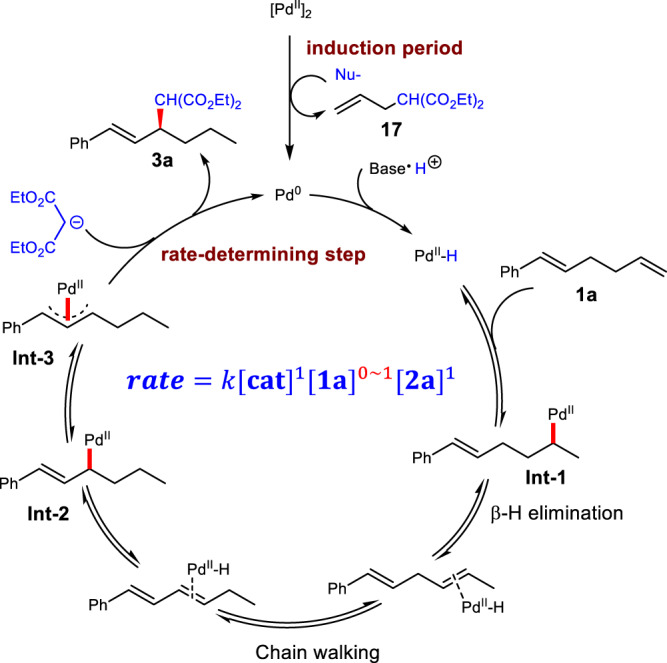

Based on the above facts and reported work on the studies of chain walking36–41, a plausible mechanism was proposed as shown in Fig. 6. The proton would first oxidatively add to Pd(0) to generate PdH species in situ which then inserted into the less sterically hindered alkene to give an unstable alkylpalladium intermediate Int-1. After iterative β-H elimination and hydrometallation, a thermodynamically stable ƞ3-π-allyl Pd species Int-3 was formed. Finally, the regio- and enantioselective outer-sphere nucleophilic substitution was conducted to deliver the allylation product 3a and regenerate the Pd(0) catalyst.

Fig. 6. Proposed mechanism.

Pd-catalyzed migratory allylic substitution with outer-sphere nucleophiles.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have established a reliable protocol to realize challenging enantioselective acyclic allylic C(sp3)−H functionalization. Hydropalladation is used to trigger stereoselective chain-walking, which is combined with ƞ3-allylation to construct a carbon−carbon stereogenic center from an inert C−H bond in high yields and enantioselectivities and 100% atom-efficiency. Studies on the correlation between the pKa of the nucleophiles with the chain-walking and allylation processes showed the origins of the pKa range of nucleophiles (pKa = ~13 to ~18) and the potential factors controlling the reactivity. Importantly, the products could be derivatized to access diverse valuable enantiopure structures of biologically active compounds. Mechanistic studies showcased the designed merger of chain walking and allylic substitution. This strategy might open new avenues for achieving diverse inert C(sp3)−H functionalizations.

Methods

General procedure for the Pd-catalyzed migratory allylic functionalization

To a 4 mL vial in the glovebox under nitrogen were added [Pd(allyl)Cl]2 (1.8 mg, 0.0050 mmol), L9 (5.6 mg, 0.010 mmol), sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaBArF4, 8.8 mg, 0.010 mmol) and dry Et3N (0.2 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 min. Then the skipped diene 1 (0.22 mmol) was added to the solution and the reaction continued to stir for 1 min. Finally, the nucleophile 2 (0.20 mmol) was added to the reaction and the resulting mixture was stirred at 60 oC for 24 h. After this time, the crude mixture was cooled to room temperature, condensed, and crude 1H NMR was obtained with dibromomethane (7 µL, 0.1 mmol) as an internal standard to help determine the regioselectivity and conversion. The reaction was further purified by flash column chromatography to afford the pure allylation product 3−4.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 22071262, 21871284, 91956113), Shanghai Rising-Star program (20QA1411300), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (18401933502), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB 20020100), CAS Key Laboratory of Synthetic Chemistry of Natural Substances, and Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry. We thank Prof. John F. Hartwig (UC Berkeley), Qilong Shen (SIOC), and Zheng Huang (SIOC) for insightful discussions.

Author contributions

Z.-T.H. conceived the project. Y.-W.C., Y.L., and H.-Y.L. performed the experiments, collected and analyzed the data. G.-Q.L. and Z.-T.H. directed this work. Z.-T.H. wrote the paper with the feedback from all authors.

Data availability

For experimental details and procedures, spectra for all unknown compounds, see supplementary files. The X-ray crystallographic data for 11 (CCDC 2076792), have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review informationNature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ye-Wei Chen, Yang Liu.

Contributor Information

Guo-Qiang Lin, Email: lingq@sioc.ac.cn.

Zhi-Tao He, Email: hezt@sioc.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-25978-6.

References

- 1.Trost BM, Vranken Van, Asymmetric DL. transition metal-catalyzed allylic alkylations. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395–422. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu Z, Ma S. Metal-catalyzed enantioselective allylation in asymmetric synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:258–297. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poli, G. et al. Transition Metal Catalyzed Enantioselective Allylic Substitution in Organic Synthesis Vol. 38 (ed Kazmaier, U.) (Springer, 2012).

- 4.Butt NA, Zhang W. Transition metal-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions with unactivated allylic substrates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:7929–7967. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00144G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Süsse L, Stoltz BM. Enantioselective formation of quaternary centers by allylic alkylation with first-row transition-metal catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:4084–4099. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pàmies O, et al. Recent advances in enantioselective Pd-catalyzed allylic substitution: from design to applications. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:4373–4505. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li G, Huo X, Jiang X, Zhang W. Asymmetric synthesis of allylic compounds via hydrofunctionalisation and difunctionalisation of dienes, allenes, and alkynes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49:2060–2118. doi: 10.1039/C9CS00400A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamson NJ, Malcolmson SJ. Catalytic enantio- and regioselective addition of nucleophiles in the intermolecular hydrofunctionalization of 1,3-dienes. ACS Catal. 2020;10:1060–1076. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b04712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang R, Luan Y, Ye M. Transition metal-catalyzed allylic C(sp3)–H functionalization via η3-allylmetal intermediate. Chin. J. Chem. 2019;37:720–743. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.201900140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang P-S, Gong L-Z. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic C−H functionalization: mechanism, stereo- and regioselectivities, and synthetic applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:2841–2854. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chai Z, Rainey TJ. Pd(II)/Brønsted acid catalyzed enantioselective allylic C–H activation for the synthesis of spirocyclic rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:3615–3618. doi: 10.1021/ja2102407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trost BM, Thaisrivongs DA, Donckele EJ. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective allylic alkylations through C–H activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:1523–1526. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trost BM, Donckele EJ, Thaisrivongs DA, Osipov M, Masters JT. A new class of non-C2-symmetric ligands for oxidative and redox-neutral palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylations of 1,3-diketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:2776–2784. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang P-S, Lin H-C, Zhai Y-J, Han Z-Y, Gong L-Z. Chiral counteranion strategy for asymmetric oxidative C(sp3)–H/C(sp3)–H coupling: enantioselective α-allylation of aldehydes with terminal alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:12218–12221. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang P-S, et al. Asymmetric allylic C–H oxidation for the synthesis of chromans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:12732–12735. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin H-C, et al. Highly enantioselective allylic C–H alkylation of terminal olefins with pyrazol-5-ones enabled by cooperative catalysis of palladium complex and Brønsted acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:14354–14361. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang P-S, Shen M-L, Wang T-C, Lin H-C, Gong L-Z. Access to chiral hydropyrimidines through palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic C–H amination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:16032–16036. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin H-C, et al. Nucleophile-dependent Z/E- and regioselectivity in the palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic C–H alkylation of 1,4-dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:5824–5834. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang T-C, Fan L-F, Shen Y, Wang P-S, Gong L-Z. Asymmetric allylic C-H alkylation of allyl ethers with 2-acylimidazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:10616–10620. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b05247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ammann SE, Liu W, White MC. Enantioselective allylic C–H oxidation of terminal olefins to isochromans by palladium(II)/chiral sulfoxide catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:9571–9575. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu W, Ali SZ, Ammann SE, White MC. Asymmetric allylic C–H alkylation via palladium(II)/cis-ArSOX catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:10658–10662. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b05668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Covell DJ, White MC. A chiral Lewis acid strategy for enantioselective allylic C–H oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6448–6451. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. Catalytic asymmetric allylic and homoallylic diamination of terminal olefins via formal C−H activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8590–8591. doi: 10.1021/ja8027394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takenaka K, Akita M, Tanigaki Y, Takizawa S, Sasai H. Enantioselective cyclization of 4-alkenoic acids via an oxidative allylic C–H esterification. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3506–3509. doi: 10.1021/ol201314m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunno Y, Tsukimawashi Y, Kojima M, Yoshino T, Matsunaga S. Metal-containing Schiff base/sulfoxide ligands for Pd(II)-catalyzed asymmetric allylic C−H aminations. ACS Catal. 2021;11:2663–2668. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c05261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werner EW, Mei T-S, Burckle AJ, Sigman MS. Enantioselective Heck arylations of acyclic alkenyl alcohols using a redox-relay strategy. Science. 2012;338:1455–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1229208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mei T-S, Patel HH, Sigman MS. Enantioselective construction of remote quaternary stereocentres. Nature. 2014;508:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nature13231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu S, Niljianskul N, Buchwald SL. A direct approach to amines with remote stereocentres by enantioselective CuH-catalysed reductive relay hydroamination. Nat. Chem. 2016;8:144–150. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruffaerts J, Pierrot D, Marek I. Efficient and stereodivergent synthesis of unsaturated acyclic fragments bearing contiguous stereogenic elements. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:1164–1170. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0123-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Cheng Z, Guo J, Lu Z. Asymmetric remote C-H borylation of internal alkenes via alkene isomerization. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3939. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06240-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, Yuan Q, Toste FD, Sigman MS. Enantioselective construction of remote tertiary carbon–fluorine bonds. Nat. Chem. 2019;11:710–715. doi: 10.1038/s41557-019-0289-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou, F., Zhang, Y., Xu, X. & Zhu, S. NiH-catalyzed remote asymmetric hydroalkylation of alkenes with racemic α-bromo amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.58, 1754−1758 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Yu R, Shanmugam R, Fang X. Enantioselective nickel-catalyzed migratory hydrocyanation of nonconjugated dienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:21436–21441. doi: 10.1002/anie.202008854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross SP, Rahman AA, Sigman MS. Development and mechanistic interrogation of interrupted chain-walking in the enantioselective relay Heck reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:10516–10525. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c03589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, Ding C, Yin G. Catalyst-controlled enantioselective 1,1-arylboration of unactivated olefins. Nat. Catal. 2020;3:951–958. doi: 10.1038/s41929-020-00523-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vasseur A, Bruffaerts J, Marek I. Remote functionalization through alkene isomerization. Nat. Chem. 2016;8:209–219. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommer H, Juliá-Hernández F, Martin R, Marek I. Walking metals for remote functionalization. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018;4:153–165. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kochi T, Kanno S, Kakiuchi F. Nondissociative chain walking as a strategy in catalytic organic synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019;60:150938. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dhungana RK, Sapkota RR, Niroula D, Giri R. Walking metals: catalytic difunctionalization of alkenes at nonclassical sites. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:9757–9774. doi: 10.1039/D0SC03634J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Wu D, Cheng H-G, Yin G. Difunctionalization of alkenes involving metal migration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:7990–8003. doi: 10.1002/anie.201913382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janssen-Müller D, Sahoo B, Sun S-Z, Martin R. Tackling remote sp3 C−H functionalization via Ni-catalyzed “chain-walking” reactions. Isr. J. Chem. 2020;60:195–206. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201900072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, et al. Access to chiral tetrahydrofluorenes through a palladium-catalyzed enantioselective tandem intramolecular Heck/Tsuji–Trost reaction. Chem. Commun. 2019;55:3769–3772. doi: 10.1039/C9CC01379B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu D, et al. Asymmetric three-component Heck arylation/amination nonconjugated cyclodienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:5341–5345. doi: 10.1002/anie.201915864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larock RC, Lu YD, Bain AC, Russell CE. Palladium-catalyzed coupling of aryl iodides, nonconjugated dienes and carbon nucleophiles by palladium migration. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:4589–4590. doi: 10.1021/jo00015a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larock RC, Wang Y, Lu Y, Russell CA. Synthesis of aryl-substituted allylic amines via palladium-catalyzed coupling of aryl iodides, nonconjugated dienes, and amines. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:8107–8114. doi: 10.1021/jo00105a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han, X. & Larock, R. C. Synthesis of highly functionalized polycyclics via Pd-catalyzed intramolecular coupling of aryl/vinylic halides, non-conjugated dienes, and nucleophiles. Synlett1998, 748−750 (1998).

- 47.Larock RC, Han X. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of 2,5-cyclohexadienyl-substituted aryl or vinylic iodides and carbon or heteroatom nucleophiles. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1875–1887. doi: 10.1021/jo981876f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Dong X, Larock RC. Synthesis of naturally occurring pyridine alkaloids via palladium-catalyzed coupling/migration chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:3090–3098. doi: 10.1021/jo026716p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pang H, Wu D, Cong H, Yin G. Stereoselective palladium-catalyzed 1,3-arylboration of unconjugated dienes for expedient synthesis of 1,3-disubstituted cyclohexanes. ACS Catal. 2019;9:8555–8560. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b02747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grushin VV. Hydrido complexes of palladium. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2011–2034. doi: 10.1021/cr950272y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trost BM. When is a proton not a proton? Chem. Eur. J. 1998;4:2405–2412. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3765(19981204)4:12<2405::AID-CHEM2405>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawatsura M, Hartwig JF. Palladium-catalyzed intermolecular hydroamination of vinylarenes using arylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9546–9547. doi: 10.1021/ja002284t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Löber O, Kawatsura M, Hartwig JF. Palladium-catalyzed hydroamination of 1,3-dienes: A colorimetric assay and enantioselective additions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:4366–4367. doi: 10.1021/ja005881o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lutete LM, Kadota I, Yamamoto Y. Palladium-catalyzed intramolecular asymmetric hydroamination of alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1622–1623. doi: 10.1021/ja039774g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou H, Wang Y, Zhang L, Cai M, Luo S. Enantioselective terminal addition to allenes by dual chiral primary amine/palladium catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:3631–3634. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adamson NJ, Hull E, Malcolmson SJ. Enantioselective intermolecular addition of aliphatic amines to acyclic dienes with a Pd−PHOX catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:7180–7183. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adamson NJ, Wilbur KCE, Malcolmson SJ. Enantioselective intermolecular Pd-catalyzed hydroalkylation of acyclic 1,3-dienes with activated pronucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:2761–2764. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nie S-Z, Davison RT, Dong VM. Enantioselective coupling of dienes and phosphine oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:16450–16454. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Q, et al. Stereodivergent coupling of 1,3-dienes with aldimine esters enabled by synergistic Pd and Cu catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:14554–14559. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b07600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park S, Adamson NJ, Malcolmson SJ. Brønsted acid and Pd−PHOX dual-catalyzed enantioselective addition of activated C-pronucleophiles to internal dienes. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:5176–5182. doi: 10.1039/C9SC00633H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, et al. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective thiocarbonylation of styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:12264–12270. doi: 10.1002/anie.201905905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Q, Dong D, Zi W. Palladium-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective hydrosulfonylation of 1,3-dienes with sulfinic acids: scope, mechanism, and origin of selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:15860–15869. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c05976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li M-M, Cheng L, Xiao L-J, Xie J-H, Zhou Q-L. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrosulfonylation of 1,3-dienes with sulfonyl hydrazides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:2948–2951. doi: 10.1002/anie.202012485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu M, Zhang Q, Zi W. Diastereodivergent synthesis of β-amino alcohols through dual-metal-catalyzed coupling of alkoxyallenes with aldimine esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:6545–6552. doi: 10.1002/anie.202014510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao Y-H, et al. Asymmetric Markovnikov hydroaminocarbonylation of alkenes enabled by palladium-monodentate phosphoramidite catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:85–91. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c11249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang S-Q, Wang Y-F, Zhao W-C, Lin G-Q, He Z-T. Stereodivergent synthesis of tertiary fluoride-tethered allenes via copper and palladium dual catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:7285–7291. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c03157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trost BM, Bunt RC. On ligand design for catalytic outer sphere reactions: a simple asymmetric synthesis of vinylglycinol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996;35:99–102. doi: 10.1002/anie.199600991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luzung MR, Mauleón P, Toste FD. Gold(I)-catalyzed [2 + 2]-cycloaddition of allenenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12402–12403. doi: 10.1021/ja075412n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Snider BB, Lu Q. Syntheses of (±)-raikovenal, (±)-preraikovenal, and (±)-epiraikovenal. Synth. Commun. 1997;27:1583–1600. doi: 10.1080/00397919708006097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ainsworth, S. in Steady-State Enzyme Kinetics (Palgrave, 1977).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For experimental details and procedures, spectra for all unknown compounds, see supplementary files. The X-ray crystallographic data for 11 (CCDC 2076792), have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.