Abstract

Fengycin is an important lipopeptide antibiotic that can be produced by Bacillus subtilis. However, the production capacity of the unmodified wild strain is very low. Therefore, a computationally guided engineering method was proposed to improve the fengycin production capacity. First, based on the annotated genome and biochemical information, a genome-scale metabolic model of Bacillus subtilis 168 was constructed. Subsequently, several potential genetic targets were identified through the flux balance analysis and minimization of metabolic adjustment algorithm that can ensure an increase in the production of fengycin. In addition, according to the results predicted by the model, the target genes accA (encoding acetyl-CoA carboxylase), cypC (encoding fatty acid beta-hydroxylating cytochrome P450) and gapA (encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) were overexpressed in the parent strain Bacillus subtilis 168. The yield of fengycin was increased by 56.4, 46.6, and 20.5% by means of the overexpression of accA, cypC, and gapA, respectively, compared with the yield from the parent strain. The relationship between the model prediction and experimental results proves the effectiveness and rationality of this method for target recognition and improving fengycin production.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-021-02990-7.

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis 168, Fengycin, Target prediction, Metabolic network, Genome-scale metabolic model

Introduction

Fengycin, produced by Bacillus subtilis, is composed of a β-hydroxy fatty acid linked to a peptide part comprising ten amino acids, including eight in a cycle (Deleu et al. 2005). Fengycin is biosynthesized by five non-ribosomal peptide synthetases, Fen1–Fen5, respectively, coded by the genes fenA–E (Zhao et al. 2016). More importantly, fengycin has antifungal activity against filamentous fungi and its hemolytic activity is 40 times lower than that of surfactin (Deleu et al. 2005). The biological activity of fengycin is equivalent to that of some chemical pesticides. It can significantly inhibit the growth of plant fungi, but it has no obvious inhibitory effect on yeast and bacteria (Vanittanakom et al. 1986). Non-ribosomal peptide antibiotics such as fengycin generally have relatively unique biological activity. For the microorganisms that can produce such antibiotics themselves, these non-ribosomal peptide antibiotics can help them better adapt to the living environment, especially in when encountering survival and competition with other fungi or bacteria, it can inhibit or kill opponents, greatly improving its own competitiveness. Fengycin has been developed as a variety of antifungal drugs, and strains with mutations or deletions in the fengycin synthase gene have a significant decrease in their antagonistic effect on pathogenic fungi (Deleu et al. 2005), which also proves that fengycin is effective in preventing and treating plants. Recently, the pharmacological importance and wide range of applications of fengycin have attracted increasing attention from many researchers and pharmaceutical companies.

At present, the low production of fengycin is still the bottleneck for further commercialization and industrialization, and a lot of work has been done in strain alteration and culture optimization. Four strategies have mainly been used to improve the production of fengycin: (a) traditional physical and chemical mutagenesis (Henne et al. 2004); (b) genetic engineering methods (Zhao et al. 2016); (c) optimization of the biological production process (Rangarajan et al. 2015); (d) adopting different strain culture conditions (Yaseen et al. 2017). However, mutagenesis, genome shuffling, the optimization of the production process and culture conditions are tiring and complicated processes and sometimes require long durations of work, and the results are unpredictable. In recent years, metabolic engineering technology has demonstrated great advantages in improving the yield of natural products due to its accurate gene target positioning and short operation cycle.

Recently, great effort based on random mutagenesis and gene selection manipulation methods has been devoted to the development of effective fengycin synthesis. As the main bottleneck, the production of fengycin during fermentation is relatively low, which may be due to the limited level of intracellular precursors. Therefore, strains must be engineered to increase the demand of precursors for product formation. Indeed, metabolic engineering could efficiently adjust the key pathways of natural products such as non-ribosomal peptides and polyketides (Dang et al. 2016). For example, it was reported that the inactivation of polynucleotide phosphorylase reduced the production of fengycin in BBG235 and BBG236 strains (Yaseen et al. 2018). Dong et al. (2014) have confirmed that the phoP gene was a positively regulation factor for fengycin production in Bacillus subtilis NCD-2. Tao et al. (2014) knocked out the bmy gene in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Q-426. The experimental results showed that the hemolytic activity and antifungal activity of the fermentation broth was significantly reduced, proving that the bmy gene can significantly affect the production of fengycin and bacillomycin D. Although genetic manipulation in strains can increase the yield of target product precursors, but it is usually uncertain what specific changes will be made to the metabolism of the strain by changing the expression of a gene, so the verification of the target gene is usually uncertain and unpredictable. In addition, because of the complex and interrelated metabolic network of microorganisms, manipulation of the specific gene may affect other metabolic pathways. Therefore, it is challenging to comprehensively evaluate cell behavior at the system level and determine accurate target genes to effectively improve strains. With the increasing maturity of the genome-scale metabolic network model (GSMM) and the continuous improvement of model analysis methods, GSMM based on system biology can comprehensively and accurately analyze the metabolic flux distribution of microorganisms, thereby determining the target of genetic transformation, improving the ability of strains to produce target products, and playing an increasingly important role in strain metabolic engineering (Wang et al. 2017). With the development of high-throughput sequencing technology and the reduction in sequencing costs, more and more microorganisms have been sequenced. The construction of GSMM based on genome sequence annotation and detailed biochemical information integration provides the best platform for global understanding and rational regulation of the physiological and metabolic functions of microorganisms. The complete genome of Bacillus subtilis was sequenced by Kunst et al. (1997), providing the foundation for constructing the genome-scale metabolic model and obtaining integrated insight into Bacillus subtilis physiology. Stoichiometric model-based GSMM can be employed to interpret cellular metabolic response to genetic perturbation and unravel the underlying reasons of undesired phenotypes. This method saves time, research costs, and labor by reducing the number of wet experiments. Currently, GSMMs have been used in the metabolic engineering of many important industrial products, such as amino acids, vitamins, biofuels and secondary metabolites (Park et al. 2007; Alper et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2005; Yim et al. 2011).

Although Bacillus subtilis 168 contains a complete fengycin synthetase gene cluster, it cannot synthesize 4'-phosphopantetheine transferase (PPtase) due to the frameshift mutation of the sfp gene required in the non-ribosomal peptide synthesis pathway, so lipopeptide compounds cannot be synthesized. However, the yield of the 168 strain fengycin, which was only transfected with the sfp gene, was still very low. The reason was that a base T at the position of -10 in the promoter region of degQ gene changed into C, so the strain could not express the degQ gene. The degQ gene is a pleiotropic factor widely present in Bacillus, encoding a 46 amino acid polypeptide that can regulate the expression of a variety of exocrine enzymes and the production of antibacterial substances (LI 2015). In this study, the sfp from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 and the degQ from Bacillus subtilis 168 were cloned to construct the expression vector pHP13-P43-sfp-degQ, which was subsequently transferred to a Bacillus subtilis 168 strain that cannot produce fengycin to give it the ability to produce fengycin. This artificial strain was named BSP000. In addition, a GSMM of BSP000 was reconstructed to simulate the intracellular flux distribution. Guided by FBA and MOMA prediction, several target genes were identified.

Materials and methods

GSMM reconstruction for Bacillus subtilis

The genome-scale metabolic network for Bacillus subtilis 168 was reconstructed according to Kwan et al. (Oh et al. 2007). The first genome sequence draft of Bacillus subtilis 168 has been reported recently. Bacillus subtilis 168 genome length is 4.21 MB, coding 4100 genes, with 43.5% GC content (Kunst et al. 1997), which were stored in the KEGG, NCBI, and other databases. In this study, genes, enzyme complexes, and reactions were identified through the pathway map of the KEGG database, and the sfp and degQ genes were introduced into the bacteria to form an initial metabolic network. We used public databases such as KEGG, BRENDA, and BiGG to manually refine the metabolic network draft. Identifying the gaps in the metabolic network and selecting strong evidence to fill the gaps in the candidate are the biggest challenges for model optimization (Dang et al. 2016). The Gapfind function can identify the gaps of the coarse network model, and the Gapfilling function can provide some alternative responses, which provides convenience for manually optimizing the model (Kumar et al. 2007). Combining the literature and biochemical knowledge allowed us to confirm the gene and response information that filled the gaps. Some responses from the experimental data and published literature were also supplemented in the network. The main metabolic pathways of the constructed Bacillus subtilis model included the glycolytic pathway, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, fengycin biosynthesis, etc. The refined model is shown in File S1 in Supplementary Materials.

Target gene prediction

First, we read the xml format model (file S2 in the supplementary material) on the MATLAB platform, and then used the FBA algorithm to obtain the initial flux distribution with the maximum growth rate as the objective function. Subsequently, we amplified each non-zero reaction flux to some extent (for example, twofold), and used the MOMA algorithm to solve the quadratic programming problem (Segre et al. 2002). Finally, using constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA), overexpression targets for improving fengycin production were identified (Boghigian et al. 2012) through comparing the fPH value. Overexpressing genes with higher fPH was more suitable for manipulation through experiments:

Strains, plasmids, and cultivation conditions

All strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1. E. coli DH5α was used to propagate all plasmids. All B. subtilis mutants were derived from the original B. subtilis 168 strain. E. coli and B. subtilis strains were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 37 °C The vector pHY300PLK integrated with the P43 promoter was used for gene overexpression in Bacillus subtilis.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains or plasmids | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | Wild type | Lab collection |

| B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42 | Wild type | ATCC |

| B. subtilis 168 | Wild type | Lab collection |

| BSP000 | B. subtilis harboring pHP13-P43-sfp-degQ | This work |

| BSP00A | BSP000 harboring pHY300PLK-P43-accA | This work |

| BSP00C | BSP000 harboring pHY300PLK-P43-cypC | This work |

| BSP00G | BSP000 harboring pHY300PLK-P43-gapA | This work |

| BSP002 | BSP000 harboring pHY300PLK-P43-accA-cypC | This work |

| BSP003 | BSP000 harboring pHY300PLK-P43-accA-cypC-gapA | This work |

| BSP004 | B. subtilis harboring pHP13 | This work |

| BSP005 | B. subtilis harboring pHP13 and pHY300PLK | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHP13 | E. coli cloning vector; Cm | Lab collection |

| pHP13-P43-sfp-degQ | pHP13 with P43-controlled sfp and degQ | This work |

| pHY300PLK | E. coli cloning vector; Amp | Lab collection |

| pHY300A | pHY300PLK with P43-controlled accA | This work |

| pHY300C | pHY300PLK with P43-controlled cypC | This work |

| pHY300G | pHY300PLK with P43-controlled gapA | This work |

| pHY300AC | pHY300PLK with P43-controlled accA and cypC | This work |

| pHY300ACG | pHY300PLK with P43-controlled accA, cypC and gapA | This work |

Bacillus subtilis 168 strain stored at − 80 °C was used for inoculation of LB medium for 12 h. Then, we picked the activated bacterial solution and streaked it on agar slant medium and cultivated it at 37 °C for 16 h to obtain a single colony. We picked a single colony and inoculated it in LB liquid medium, and incubated the sample at 37 °C and 220 rpm for 12 h. Then, an 8.5 mL seed culture was transferred into a 250 mL unbaffled shake flask containing 100 mL fermentation medium, and cultured at 37 °C and 190 rpm for 56 h.

The seed medium was composed of 10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast powder, and 10 g/L NaCl, and had a pH of 7.0. The fermentation medium contained 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L tryptone, 0.154 g/L NaH2PO4, 0.4 g/L Na2HPO4·2H2O and 0.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, and had a pH of 7.2.

Gene cloning, plasmid construction, and transformation

Every DNA operation was performed according to the standard protocols (Sambrook and Russell 2001). All primers used in this work are listed in Table 2. When target genes were overexpressed, we selected P43 as a strong promoter for gene expression; P43, accA, cypC, and gapA were amplified from genomic DNA of B. subtilis using primer pairs of P43-F2/P43-R2, accA-F/accA-R, cypC-F/cypC-R, and gapA-F/gapA-R, respectively. The PCR product of P43 gene was digested by restriction enzymes HindIII and BamHI. Then, it was cloned into pHY300PLK, which was digested with the same restriction enzymes to get pHY300P. We used the same method to digest the accA, cypC, and gapA genes with restriction enzymes BglII-XhoI, XhoI-XbaI, XbaI-BamHI, respectively, and cloned them into pHY300P to obtain pHY300A, pHY300C, and pHY300G, respectively. For the construction of pHY300ACG carrying triple genes, the PCR product of cypC was excised with XhoI-XbaI and transferred to the same sites of pHY300A, generating pHY300AC. Then, the PCR product of gapA was digested with XbaI-BamHI and transferred to the XbaI-BamHI sites of pHY300AC, generating pHY300ACG. Each constructed plasmid was transformed into E. coli DH5α, which was subsequently introduced into B. subtilis 168 through spizzen transfer (Chen et al. 2013). The positive exconjugants were verified by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing with primer pair pHY-F/pHY-R. The locations of pHY-F/pHY-R in pHY300PLK are shown in File S3 in Supplementary Materials.

Table 2.

Primers and their sequences used in this work

| Primer | Function | Sequence 5ʹ → 3ʹ |

|---|---|---|

| P43-F1 | Amplification of P43 | CCCAAGCTTGCGGCTTCCTTGTAGAGCTCAGC (HindIII) |

| P43-R1 | CGCGGATCCCTCGAGACGCGTGCATGCTCTAGAAGATCTCTGCAGGTCGACCATGTGTACATTCCTCTC (BamHI) | |

| sfp-F | Amplification of sfp | GCGTCGACCCAAGGAGGGTATAGCTATGAAAATTTACGGAGTATATATG (SalI) |

| sfp-R | GAAGATCTTTATAACAGCTCTTCATACGTTTTC (BglII) | |

| degQ-F | Amplification of degQ | GAAGATCTCCAAGGAGGGTATAGCTATGGAAAAGAAACTTGAAGAAG (BglII |

| degQ-R | CGGAATTCTTTCTCCTTGATCCGGACAGAATC (EcoRI) | |

| P43-F2 | Amplification of P43 | CCAAGCTTTGATAGGTGGTATGTTTTCGCT (HindIII) |

| P43-R2 | CGGATCCCAGTCTAGACACCTCGAGGCGAGATCTCATGTGTACATTC (BamHI) | |

| accA-F | Amplification of accA | GAAGATCTCCAAGGAGGGTATAGCTGTGGCTCCAAGATTAGAATTTG (BglII) |

| accA-R | CCGCTCGAGTTAGTTTACCCCGATATATTG (XhoI) | |

| cypC-F | Amplification of cypC | CGCTCGAGCCAAGGAGGGTATAGCTATGAATGAGCAGATTCCACATG (XhoI) |

| cypC-R | GCTCTAGATTAACTTTTTCGTCTGATTCCG (XbaI) | |

| gapA-F | Amplification of gapA | GCTCTAGACCAAGGAGGGTATAGCTATGGCAGTAAAAGTCGGTATT (XbaI) |

| gapA-R | CGGGATCCTTAAAGACCTTTTTTTGCGATG (BamHI) | |

| pHY-F | Sequencing of overexpressed strains | GGCAGGAACAGGAGAGCGCACGAG |

| pHY-R | GGTTGTTACCTATGGAAGTTGATCAGTC |

Underlined parts: the restriction enzyme cutting site

Analytical methods

We diluted the sample appropriately, measured its absorbance at a wavelength of 600 nm, and recorded it as the OD600. We then centrifuged 10 mL of the bacterial solution (4 °C, 4000 rpm) and washed it with deionized water three times, and then filtered it with filter paper. Subsequently, we dried the filter paper and its cells at 105 °C to a constant weight, and determined the dry cell weight (DCW). The glucose concentration was measured using a biosensor analyzer (Liu et al. 2015). The concentration of fengycin was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (1200; Agilent Technologies, USA) equipped with a Zorbax SB-C18 analytical column (250 mm × 4.6 mm; Agilent Technologies). We took 10 mL of the fermentation broth and centrifuged it at 8000 ×g for 30 min to remove the bacteria, and adjusted the pH to 2.0 with concentrated hydrochloric acid for precipitation overnight. Then, the precipitate was obtained by centrifugation at 8000 ×g for 30 min. The precipitate was extracted with 5 mL of methanol and adjusted to pH 7.0. After 5 h, the extract was taken and centrifuged to remove the precipitate. The crude fengycin sample was prepared by passing the supernatant through a 0.22 μmol·L−1 microporous membrane. We took 20 μL for HPLC analysis. The mobile phase was composed of acetonitrile, water, and trifluoroacetic acid (100:100:1, v/v/v) with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min, using a UV detector at 210 nm, and the column temperature was 30 °C. The concentration of fengycin in the samples was measured using a calibration curve generated by authentic fengycin standards.

Results

GSMM construction for B. subtilis 168

In this study, B. subtilis 168 GSMM was constructed by integrating the genome annotation results and literature data. After refining, a model including 1034 reactions and 1011 metabolites was obtained. Here, by integrating the corresponding results related to other Bacillus in the experiment and references, the biomass composition was obtained (File S1 in the supplementary material). According to previous literature reports, the energy required for growth and metabolism of strains were evaluated (Oh et al. 2007). Subsequently, to achieve the correctness of the model calculation, the constraint conditions of the model calculation were set. Through the fermentation experiments of B. subtilis 168, the relevant fermentation parameters were determined, and finally the specific glucose uptake rate of the strain was set to 0.8 mmol/g DCW/h. The maximum specific growth rate of the strain calculated by the FBA algorithm was 0.1281 h−1, while the maximum specific growth rate of the strain determined by the experiment was 0.1216 h−1. The two were very close and the error was within 5.3%. It also proves that we have built a model with a relatively high accuracy rate.

Target gene identification based on in silico simulations

Preliminary simulation results were obtained using FBA and the MOMA algorithm. Target genes for improving fengycin production were identified with the aid of fPH (Boghigian et al. 2012). Reactions that produced an fPH value greater than 2 were chosen as the potential targets. Figure 1 shows the fPH of several important reactions leading to fengycin overproduction. Among these targets, pnpA had the highest ratio (fPH = 13.2). Yaseen et al. (2018) confirmed that the pnpA gene was involved in the production of fengycin. In addition, accA also had a high ratio (fPH = 11.3), indicating this pathway as a potential overexpression target. In fact, the accA gene encodes acetyl-CoA carboxylase, which catalyzes the synthesis of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which was the initial step of fatty acid synthesis. Fatty acid was an important part of fengycin, and overexpression of this gene would increase the level of fengycin synthesis (Davis et al. 2000). The next target gene to be overexpressed was cypC. Cytochrome P450 enzymes are known to hydroxylate long-chain fatty acids in Bacillus sp (Hlavica and Lehnerer 2010). In fact, cypC encodes fatty acid beta-hydroxylating cytochrome P450 enzyme, which could form 3-hydroxy fatty acid for lipopeptide biosynthesis (Youssef et al. 2011). Similarly, gapA also had a large fPH. The synthesis of fengycin requires the participation of a large number of cofactor NADPH. The metabolic reaction catalyzed by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is a key metabolic pathway regulating the reducing power of fengycin synthesis. Overexpression of gapA gene can provide more NADPH to drive fengycin synthesis.

Fig. 1.

Prediction effect of single gene perturbation on the fPH. The enzymes encoded by these genes are as follows: pnpA polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase); accA acetyl-CoA carboxylase (carboxyltransferase alpha subunit); cypC fatty acid beta-hydroxylating cytochrome P450; gapA glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ppaE non-ribosomal plipastatin synthetase E; hisD histidinol dehydrogenase; phoP two-component response regulator; yhfT putative long-chain fatty-acid-CoA ligase (proofreading for biotin synthesis)

Improving fengycin production by the perturbation of target genes

In the original Bacillus subtilis 168 strain, the sfp and degQ genes could not be expressed normally, resulting in the strain's failure to synthesize lipopeptides (Li et al. 2015). In this study, the sfp gene was introduced exogenously and connected with the P43 promoter gene, degQ gene of Bacillus subtilis 168 strain to the pHP13 expression vector to form the pHP13-P43-sfp-degQ expression vector. The constructed expression vector was introduced into the original strain of Bacillus subtilis 168 to compensate for the gene expression defect of the strain, and a strain capable of producing fengycin (named BSP000) was obtained. After selecting the target genes to be modified through model prediction, the three targets accA, cypC, and gapA were overexpressed under the promoter P43 of Bacillus subtilis 168 by constructing the plasmid pHY300ACG. The plasmid pHY300ACG was transferred into the strain BSP000 to obtain the modified strain (named BSP003). To avoid any unexpected effects due to the presence of multiple copies of the plasmid itself, the parent strain carrying the empty plasmid pHP13 (named BSP004) and the parent strain carrying the empty plasmid pHP13 and pHY300PLK (named BSP005) were used as control strains. When cultured in fermentation medium, there were no differences in morphology and cell growth between the strain BSP004 and the wild-type strain. Similarly, there were no differences in morphology and cell growth between the strain BSP005 and the wild-type strain, and the strains BSP004 and BSP005 (not shown).

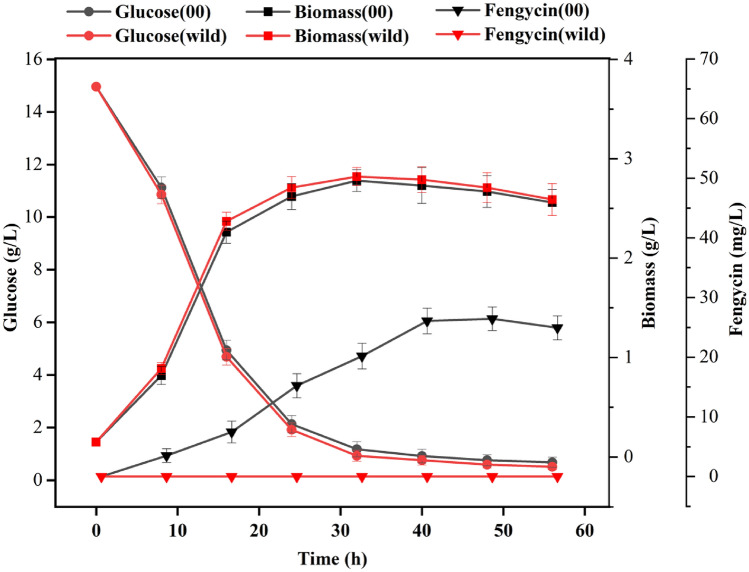

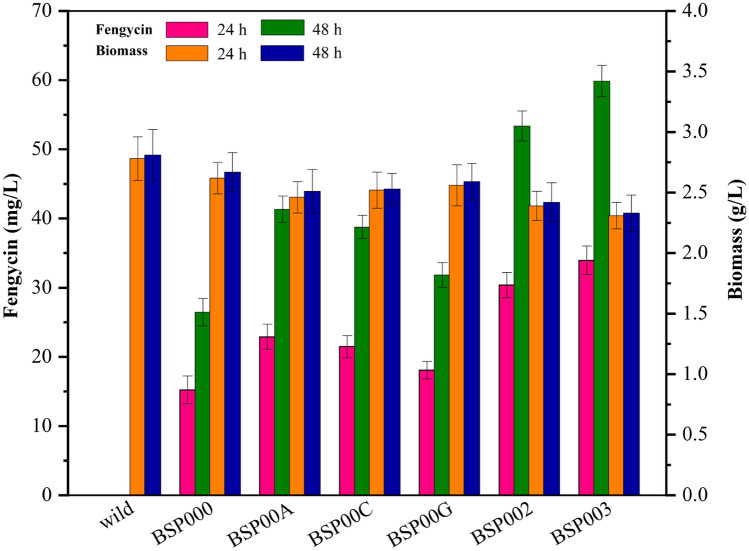

We studied the fermentation kinetic characteristics of the BSP000 strain. As shown in Fig. 2, there was no change in morphological phenotype between BSP000 and the parent strain Bacillus subtilis 168. In addition, the growth of the BSP000 strain was slightly affected, with a lower biomass concentration (2.67 ± 0.16 g/L at 48 h) as compared with the wild-type strain (2.81 ± 0.21 g/L at 48 h) and the residual glucose content of the two strains were relatively close. However, the wild-type Bacillus subtilis 168 cannot produce fengycin, but wild-type Bacillus subtilis 168 that overexpresses sfp and degQ genes (named BSP000) could produce fengycin. The growth of the two strains were synchronized. We speculate that the BSP000 strain may have sacrificed part of the biomass precursor to synthesize fengycin. In the accA-overexpressed strain BSP00A, the yield of fengycin reached 41.34 ± 1.91 mg/L at 48 h, which was 56.4% higher than the yield of BSP000 strain (26.44 ± 1.98 mg/L). The result suggests that accA gene overexpression played a positive role in fengycin production and the fatty acid synthesis pathway may be one of the rate-limited steps in the synthesis of fengycin. As shown in Fig. 3, the BSP002 strain showed an increase in fengycin titer (53.38 ± 2.16 mg/L), which was approximately 101.9% higher than that in the BSP000 strain after 48 h cultivation. BSP002 with co-expression of genes accA and cypC. The cypC gene encoded fatty acid beta-hydroxylating cytochrome P450, which functions to form 3-hydroxy fatty acids for fengycin biosynthesis. The fermentation kinetic characteristics of BSP003 was studied. As shown in Fig. 4, DCW reached 2.33 g/L in engineered strain BSP003 and 2.67 g/L in the BSP000 strain at 48 h. The growths of BSP000 and BSP003 were basically synchronous, but DCW dropped significantly with BSP003. The results show that the intracellular fluxes of BSP003 might be changed to fengycin biosynthesis through biomass precursors, which leads to an increase in fengycin biosynthesis, but a decrease in biomass, probably because cell growth and fengycin synthesis share some common precursors. Although the biomass has been greatly affected, but fengycin production reached 59.87 mg/L in BSP003 at 48 h. Production of fengycin was significantly improved by co-expression of accA, cypC, and gapA. The acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity of the obtained strain BSP00A was 0.41 ± 0.03 and 0.38 ± 0.02 U/mg at 24 and 48 h, respectively, which was approximately 2.3 times that of the wild type (0.18 ± 0.03 and 0.15 ± 0.02 U/mg at 24 and 48 h, respectively) (Table 3). Similarly, the fatty acid beta-hydroxylating cytochrome P450 activity of BSP00C strain was approximately 1.9 times that of the wild strain. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity of BSP00G strain was approximately 1.9 times that of the wild strain. These results indicate that metabolic reconstitution will significantly increase the concentration of the corresponding protein, but has little effect on the concentration of other proteins. In addition, the concentration of carbohydrate glucose of the obtained strain BSP003 was 3.31 ± 0.16 and 1.10 ± 0.23 g/L at 24 and 48 h, respectively, which was approximately 1.8 times that of the wild type (1.92 ± 0.26 and 0.59 ± 0.13 g/L at 24 and 48 h, respectively) (Table 4). This result indicates that metabolic reconstruction increases the concentration of carbohydrates. Compared with wild-type strains, the biomass of metabolic reconstruction strains has decreased, and we predicted that metabolic reconstruction will reduce the concentration of fat.

Fig. 2.

Fermentation characteristics between the wild-type B. subtilis 168 and strain BSP000 under the same culture condition. Wild represents wild-type strain B. subtilis 168, and 00 represents BSP000. The data are the average values of at least three series of three parallel tests, and error bars represent standard deviations

Fig. 3.

Experimental effect of genetic perturbation on fengycin production and cell growth. BSP000 represents the initial strain, BSP00A represents accA overexpressing strain, BSP00C represents cypC overexpressing strain, BSP00G represents gapA overexpressing strain, BSP002 represents accA and cypC co-overexpressing strain, BSP003 represents accA, cypC and gapA co-overexpressing strain. The data are the average values of at least three series of parallel tests, and error bars represent standard deviations

Fig. 4.

Fermentation characteristics between the strain BSP000 and strain BSP003 under the same culture conditions. 00 represents strain BSP000, and 03 represents BSP003. The data are the average values of at least three series of three parallel tests, and error bars represent standard deviations

Table 3.

Enzyme-specific activity of parent strain B. subtilis 168 and recombinants in batch cultures

| Strain | Time (h) | Enzyme activities (U/mg protein) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | Fatty acid beta-hydroxylating cytochrome P450 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | ||

| B. subtilis 168 | 24 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.31 ± 0.03 |

| 48 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | |

| BSP00A | 24 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.04 |

| 48 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | |

| BSP00C | 24 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.31 ± 0.03 |

| 48 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | |

| BSP00G | 24 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.05 |

| 48 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.53 ± 0.03 | |

| BSP002 | 24 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.03 |

| 48 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | |

| BSP003 | 24 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.59 ± 0.05 |

| 48 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | |

Results are represented as mean ± SD of three independent observations

Table 4.

Glucose concentration of parent strain B. subtilis 168 and recombinants in batch cultures

| Strain | Time (h) | Glucose concentration (g/L) |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis 168 | 24 | 1.92 ± 0.26 |

| 48 | 0.59 ± 0.13 | |

| BSP00A | 24 | 2.99 ± 0.31 |

| 48 | 0.97 ± 0.16 | |

| BSP00C | 24 | 2.69 ± 0.25 |

| 48 | 0.93 ± 0.24 | |

| BSP00G | 24 | 2.23 ± 0.26 |

| 48 | 0.86 ± 0.22 | |

| BSP002 | 24 | 3.16 ± 0.31 |

| 48 | 1.02 ± 0.18 | |

| BSP003 | 24 | 3.31 ± 0.36 |

| 48 | 1.10 ± 0.23 |

Results are represented as mean ± SD of three independent observations

Discussion

Compared with other lipopeptide antibiotics, fengycin has very good antifungal activity and a broad industrial application prospect. However, its application was limited because of its less research and low yield. The main purpose of our work was to break the limitation of the low yield of fengycin produced by the strain, and to explore a feasible and efficient method to improve the yield of fengycin of the target strain.

GSMM provides a method for strain optimization—system metabolic engineering. This method can be used to identify target genes when synthesizing target products, so as to increase product yield on the basis of metabolic engineering. In truth, this strategy has been successfully used to identify target genes for the improvement of biochemical products, such as isobutanol, putrescine, and tacrolimus (Li et al. 2012; Park et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2013).

In this work, the GSMM of B. subtilis 168 was constructed and used to establish gene targets for improved fengycin production. In the initial predicted targets, eight overexpression targets were finally established using FBA and the MOMA algorithm proposed by Boghigian et al. (2012). Fengycin production increased by 56.4% with accA gene overexpression. The acetyl-CoA carboxylase encoded by accA played an important role in the flux distribution of fatty acid synthesis pathway. We suggested that overexpression of accA enhanced the synthesis of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which acted as a precursor for fatty acid synthesis and indirectly promoted the synthesis of fengycin. The molecular structure of fengycin was a β-hydroxy fatty acid chain with 14–18 carbon atoms connected to the N-terminus of the peptide to form a hydrophobic tail (Schneider et al. 1999). The target gene cypC encodes the beta-hydroxylating cytochrome P450 enzyme, which functions to form 3-hydroxy fatty acids for lipopeptide biosynthesis (Yaseen et al. 2018). Microbial production of fengycin is a process that consumes reducing power. Overexpression of gapA gene maintains the metabolic balance of intracellular redox cofactors NADH and NADPH (Asanuma et al. 2009), which was a key factor in increasing the production of fengycin-synthesizing bacteria.

At present, there was no report on the specific production of fengycin synthesized by Bacillus subtilis 168, but there were some reports of other Bacillus strains synthesizing fengycin, and the research has been relatively mature. Gancel et al. (2009) added 0.35% ferric ion Fe2+ to the fengycin fermentation medium, and the final yield of Bacillus subtilis ATCC21332 strain changed from 310 to 680 mg/L, an increase of nearly 110%. Chtioui et al. (2012) used a rotating disk reactor to increase the yield of Bacillus subtilis ATCC21332 from the original 393 mg/L to the final 838 mg/L. Although the production of fengycin in this study was much lower than that of Bacillus subtilis ATCC21332, the highest yield of the modified strain was 59.87 mg/L, but the yield was increased by 126.4% compared with the initial strain. This proves that this strategy was feasible in improving the production of fengycin.

According to the prediction of GSMM, the production of fengycin was promoted through the genetic modification of target genes. However, the increase in fengycin productivity measured in the final experiment were different from the predicted increase. These differences might be caused by the failure to consider the influence of the strain's own metabolic regulation on the model during the simulation. Therefore, there were some limitations in the metabolic model based on the constraints of various indicators. Even so, the improvement in the production of fengycin proved the effectiveness of predicting metabolic engineering targets for modification. In addition, as a secondary metabolite, fengycin has a complex biosynthetic pathway, and there may be many rate-limiting steps in the synthesis pathway. If we only focus on a certain genetic modification, the production of fengycin may not be significantly promoted. Recently, multi-gene interference strategies were adopted to increase the yield of microbial products (Dang et al. 2016). The production of fengycin was further promoted by co-overexpression of genes accA, cypC, and gapA.

Conclusions

In this study, the metabolic engineering strategy guided by GSMM was used to increase the fengycin production of Bacillus subtilis 168. The fermentation characteristics of engineered strains with overexpression of accA, cypC, and gapA showed that the production capacity of fengycin was improved. The production of fengycin was further improved through co-expression of target genes accA, cypC, and gapA simultaneously. Compared with the strain BSP000 (26.44 mg/L), the titer of fengycin reached 59.87 mg/L in engineering strain BSP003, which was more than double the original value. Our method for producing fengycin is a successful example that can be used to guide the improvement of other metabolites.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Project No. 2018YFA0902201). We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contribution

MH drafted and edited the manuscript. MH, YY, PW collected the background information, MH implemented the experiment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

References

- Alper H, Jin Y-S, Moxley J, Stephanopoulos G. Identifying gene targets for the metabolic engineering of lycopene biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2005;7:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma N, Yoshizawa K, Hino T. Properties and role of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the control of fermentation pattern and growth in a ruminal bacterium Streptococcus bovis. Curr Microbiol. 2009;58(4):323–327. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boghigian BA, Armando J, Salas D, Pfeifer BA. Computational identification of gene over-expression targets for metabolic engineering of taxadiene production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:2063–2073. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3725-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Liu WX, Fu J, et al. Engineering Bacillus subtilis for acetoin production from glucose and xylose mixtures. J Biotechnol. 2013;168(4):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chtioui O, Dimitrov K, Gancel F, et al. Rotating discs bioreactor, a new tool for lipopeptides production. Process Biochem. 2012;47(12):2020–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dang L, Liu J, Wang C, et al. Enhancement of rapamycin production by metabolic engineering in Streptomyces hygroscopicus based on genome-scale metabolic model. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;44(2):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10295-016-1880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MS. Overproduction of acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity increases the rate of fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(37):32593–32598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleu M, Paquot M, Nylander T. Fengycin interaction with lipid monolayers at the air-aqueous interface implications for the effect of fengycin on biological membranes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;283(2):358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong WX, Li SZ, Lu XY, et al (2014) Regulation of fengycin biosynthase by regulator PhoP in the Bacillus subtilis strain NCD-2. Acta Phytopathologica Sinica

- Gancel F, Montastruc L, Liu T, et al. Lipopeptide overproduction by cell immobilization on iron-enriched light polymer particles. Process Biochem. 2009;44(9):975–978. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2009.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henne A, Chen XH, Liesegang H, et al. Structural and functional characterization of gene clusters directing nonribosomal synthesis of bioactive cyclic lipopeptides in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain FZB42. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(4):1084. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1084-1096.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavica P, Lehnerer M. Oxidative biotransformation of fatty acids by cytochromes P450: Predicted key structural elements orchestrating substrate specificity, regioselectivity and catalytic efficiency. Curr Drug Metabol. 2010;11:85–104. doi: 10.2174/138920010791110881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Li S, Xia M, et al. Genome-scale metabolic network guided engineering of Streptomyces tsukubaensis for FK506 production improvement. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar VS, Dasika MS, Maranas CD. Optimization based automated curation of metabolic reconstructions. BMC Bioinform. 2007;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini AM, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero MG, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390(6657):249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Lee D-Y, Kim TY, Kim BH, Lee J, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for enhanced production of succinic acid, based on genome comparison and in silico gene knockout simulation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7880–7887. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.7880-7887.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Huang D, Li Y, et al. Rational improvement of the engineered isobutanol-producing Bacillus subtilis by elementary mode analysis. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11(1):101. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wu HJ, Zhang Y et al (2015) Function of degQ and sfp and their effects on fengycin productivity of Bacillus subtilis. Chinese Journal of Biological Control

- Liu J, Qi HS, et al. Model-driven intracellular redox status modulation for increasing isobutanol production in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh YK, Palsson BO, Park SM, et al. Genome-scale reconstruction of metabolic network in Bacillus subtilis based on high-throughput phenotyping and gene essentiality data. J Biol Chem. 2007;322(39):32791–32799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Lee KH, Kim TY, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of l-valine based on transcriptome analysis and in silico gene knockout simulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702609104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Park HM, Kim WJ, Kim HU, Kim TY, Lee SY. Flux variability scanning based on enforced objective flux for identifying gene amplification targets. BMC Syst Biol. 2012;6:106. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan V, Dhanarajan G, Sen R. Bioprocess design for selective enhancement of fengycin production by a marine isolate Bacillus megaterium. Biochem Eng J. 2015;99:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2015.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 3. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Taraz K, Budzikiewicz H, et al. The structure of two fengycins from Bacillus subtilis S499. Zeitschrift Fur Naturforschung C. 1999;54(12):859–866. doi: 10.1515/znc-1999-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre D, Vitkup D, Church GM. Analysis of optimality in natural and perturbed metabolic networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:15112–15117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232349399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao SM, Zheng W, Zhao PC, et al (2014) Effects of bmy gene knockout on hemolysis and antifungal activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Q-426. China Biotechnology

- Vanittanakom N, Loeffler W, Koch U, et al. Fengycin-a novel antifungal lipopeptide antibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis F-29-3. J Antibiot. 1986;39(7):888–901. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Liu J, Liu H, et al. A genome-scale dynamic flux balance analysis model of Streptomyces tsukubaensis NRRL18488 to predict the targets for increasing FK506 production. Biochem Eng J. 2017;123:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2017.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen Y, Gancel F, Béchet M, et al. Study of the correlation between fengycin promoter expression and its production by Bacillus subtilis under different culture conditions and the impact on surfactin production. Arch Microbiol. 2017;199(10):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00203-017-1406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen Y, Diop A, Gancel F, et al. Polynucleotide phosphorylase is involved in the control of lipopeptide fengycin production in Bacillus subtilis. Arch Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00203-018-1483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim H, Haselbeck R, Niu W, Pujol-Baxley C, Burgard A, Boldt J, Khandurina J, Trawick JD, Osterhout RE, Stephen R. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:445–456. doi: 10.1038/NCHEMBIO.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef NH, Wofford N, Mcinerney MJ. Importance of the long-chain fatty acid beta-hydroxylating cytochrome P450 enzyme YbdT for lipopeptide biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis strain OKB105. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(3):1767–1786. doi: 10.3390/ijms12031767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zao J, Zhang C, Lu J, Lu Z. Enhancement of fengycin production in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens by genome shuffling and relative gene expression analysis using RT-PCR. Can J Microbiol. 2016;62(5):431–436. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2015-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.