Abstract

There is significant evidence to suggest that intimate partner violence (IPV) is associated with mental health problems including anxiety and depression. However, this research has almost exclusively been conducted through heteronormative and cisgender lenses. The current study is an exploratory, quantitative analysis of the relationship between experiences of IPV and mental health among transgender/gender nonconforming (TGNC) adults. A national sample of 78 TGNC individuals completed a survey online measuring participants’ experiences with IPV and depression, anxiety, and satisfaction with life. Of the sample, 72% reported at least one form of IPV victimization in their lifetime: 32% reported experiencing sexual IPV, 71% psychological IPV, 42% physical IPV, and 29% IPV assault with injury. All four types of IPV were positively associated with anxiety, and all but physical abuse was significantly associated with depression. None of the four types of IPV was associated with satisfaction with life. In a canonical correlation, IPV victimization and mental health had 31% overlapping variance, a large-sized effect. Sexual IPV and anxiety were the highest loading variables, suggesting that TGNC individuals who have experienced sexual IPV specifically tended to have higher levels of anxiety. These findings support previous qualitative, small-sample studies suggesting that IPV is a pervasive problem in the TGNC community. TGNC individuals who have experienced IPV may be at increased risk for mental health problems, and therefore, IPV history may trigger appropriate mental health screenings and referrals for this population in health care settings.

Keywords: transgender, gender nonconforming, anxiety, depression, intimate partner violence

Many people are familiar with statistic from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) that one in five women and 1 in 71 men will be raped in their lifetime (Black et al., 2011). However, fewer people are familiar with the estimate that one in three women and 1 in 10 men will experience intimate partner violence (IPV; Black et al., 2011). The NISVS documented IPV among both same and opposite sex couples (Coston, 2016). IPV is defined as “physical, sexual, economic, and/or emotional abuse perpetrated against an intimate partner” (Goodmark, 2013, p. 62). It can also include threats of violence, stalking, and coercion by either current or previous partners (Langenderfer-Magruder, Whitfield, Walls, Kattari, & Ramos, 2016). To date, the frameworks of IPV have been primarily based on cisgender, heterosexual relationships. There are many similarities between IPV in cisgender and transgender/gender nonconforming (TGNC) populations, including power dynamics, escalation of abuse, and its cyclical nature (Ard & Makadon, 2011). However, there are some elements of IPV unique to TGNC relationships.

TGNC individuals are a diverse group. Current estimates suggest that from 0.3% to 0.6% of U.S. adults identify as TGNC (Flores, Herman, Gates, & Brown, 2016; Gates, 2011). Witten (2016) uses 1% to 3% for population estimates. The terminology used by these individuals, for these individuals, and as self-identifiers is rapidly changing. The term “transgender” has historically been used to refer to a group “who cross or transcend culturally defined categories of gender” (Bockting & Cesaretti, 2001, p. 292). Recently, “trans,” “gender variant,” and “gender nonconforming” are used along with or in lieu of “transgender” as umbrella terms. These umbrella terms—trans(gender), gender variant, and gender nonconforming—include pre-, post-, and nonoperative trans(sexual) individuals, females-to-males trans individuals, males-to-females trans individuals, gender queer, gender fluid, bi-gender, androgynous, agender, two-spirit, drag queens, drag kings, and cross-dressers. Intersex individuals may also identify as TGNC if they also undergo a gender-identity challenge (Witten, 2003). It has been argued that the umbrella terminology of trans or gender variant is in danger of oversimplifying a population of individuals whose identities are denoted by unique combinations of sex assigned at birth, gender (including gender self-perception and gender expression), sex role, and sexual orientation (Bockting & Cesaretti, 2001; Porter, Ronneberg, & Witten, 2013). The experiences and identities encompassed by the TGNC community are varied and diverse.

IPV in TGNC Relationships

Some elements of IPV specific to the TGNC community have been identified by FORGE. FORGE (2017) is an organization started in Wisconsin in 1994 to connect trans-masculine individuals. Overtime, FORGE noticed high rates of sexual violence among the members it served, prompting the organization to investigate members’ experiences with IPV. Through their exploration, FORGE discovered six aspects of IPV particular to the TGNC community: (a) safety, outing, and disclosure, (b) community attitudes, (c) gender stereotypes and transphobia, (d) using or undermining identity, (e) violating boundaries, and (f) restricting access (Cook-Daniels, 2015).

Safety, outing, and disclosure have to do with the negative responses TGNC individuals encounter when people find out about their gender. These responses can range from rudeness to employment discrimination and violence (Cook-Daniels, 2015). In an effort to avoid these negative experiences, TGNC individuals may decide not to share their identity with others. However, TGNC individuals may be threatened with outing, or the intentional disclosure of their identities, as a form of IPV (Calton, Cattaneo, & Gebhard, 2016; Cook-Daniels, 2015; Donovan & Barnes, 2019). It should be noted that safety, outing, and disclosure are also problems for the larger lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) communities, but the experience of concealing a sexual orientation is very different from hiding a gender identity. Community attitudes are another aspect of IPV unique to TGNC relationships. Many TGNC individuals highly value their connection to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT+) communities, and through IPV, TGNC individuals may be kept from the larger LGBT+ communities and resources, or told their abuse would reflect poorly on the communities (Cook-Daniels, 2015).

Another characteristic of IPV in TGNC relationships is gender stereotypes and transphobia. Perpetrators of TGNC IPV may try to undermine or gaslight their TGNC partner’s gender by making them question or doubt their gender expression and presentation, or that the TGNC individual is somehow not a “real” man or woman (Cook-Daniels, 2015). Perpetrators may also try to undermine the TGNC target’s identity through intentional misgendering by using the wrong pronoun or the pejorative “it,” not using the individual’s chosen name, or suggesting that the TGNC target’s identity somehow undermines the perpetrator’s (Cook-Daniels, 2015). Another aspect of IPV is the violation of boundaries. While this characteristic is a common tactic of all abusers, for TGNC individuals, these violations can include not respecting the TGNC individual’s wishes for the terminology to use about their body, touching parts of the body that are deemed off limits, and/or fetishizing the TGNC individual’s body (Cook-Daniels, 2015). The last aspect of IPV FORGE identified is restricting access to medication, items, or resources that aid in a TGNC individual’s gender such as “hiding, destroying, or refusing to pay for hormones, prosthetics, and clothes” (Cook-Daniels, 2015, pp. 129-130).

Prevalence of IPV in the TGNC Community

The scope of IPV in TGNC relationships can be difficult to capture, as it often gets classified as general violence or hate crimes (Goodmark, 2013). This is both a result of institutional barriers to recognizing and classifying violence against TGNC individuals as survivors of IPV, and differentiating IPV from hate crimes, bullying, or ordinary assaults (Goodmark, 2013). As a result, when reporting violence in the TGNC community, it is important to realize that IPV may be captured in other related forms of violence (e.g., harassment, stalking, rape, and assault with or without a weapon). In addition, measures of IPV often look at lifetime prevalence or rates within a given timeframe. For TGNC individuals, this unfortunately does not capture at what point in the individual’s gender journey and transition the violence took place. This can limit the ability to attribute experiences of IPV to being TGNC but does not limit the prevalence or impact of these experiences with violence. Due to these challenges, a range of violent experiences are often reported along with IPV to contextualize the experience of violence in the community.

A few national studies have explored experiences of violence in the TGNC community over the past 20 years. Goodmark (2013) summarized data collected between 1996 and 1997, in which almost 60% of TGNC people experienced either violence or harassment, over half experienced verbal abuse, 23% were stalked or followed, almost 20% were assaulted without a weapon, 10% were assaulted with a weapon, and almost 14% experienced rape or sexual abuse in their lifetime. The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP) releases yearly reports on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) and HIV-affected IPV since 1998. Data are collected from individuals who seek services in states with NCAVP programs. The 2015 report includes information from 1,976 individuals from 17 sites across 11 states (NCAVP, 2016). The report found that 46% of IPV homicides were trans women, all of whom were trans women of color (NCAVP, 2016). Trans women of color are frequently the victims of fatal violence, with 80% of the six reported deaths on record so far in 2018 being trans women of color (Human Rights Campaign, 2018). This is likely an intersectional issue, resulting from the multiple marginalized identities of trans women of color. In addition, although 10% of the survivors in the report identified as trans, trans survivors were three times more likely than cisgender survivors to experience stalking, and trans women were three times more likely than cisgender women to report sexual violence and financial violence (NCAVP, 2016).

In addition, in a 2015 meta-analysis, lifetime IPV prevalence rates for TGNC individuals were between 31.3% and 50% (Brown & Herman, 2015; Yerke & DeFeo, 2016). In the 2011 National Transgender Discrimination Survey (N = 6,450), 61% had been the victim of physical assault, 64% had experienced sexual assault, and 19% had experienced domestic violence (DV) by a family member because of their gender (Grant et al., 2011). Those who had experienced DV reported four times the rate of homeless, were four times more likely to engage in sex work, had double the rates of HIV, and were twice as likely to have attempted suicide (Grant et al., 2011). In the follow-up 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (N = 27,715), 10% had experienced family violence (this may include experiences of IPV), 47% had been sexually assaulted in their lifetime, 10% had been sexually assaulted in the past year, and 54% had experienced IPV (James et al., 2016). In comparison to non-TGNC sexual minorities, in a study of lifetime prevalence of IPV among non-TGNC sexual minority men, participants reported as follows: 34.8% sexual abuse, 38.2% physical abuse, 69.7% psychological abuse, and 28.1% suffered an IPV-related injury (Goldberg-Looney, Perrin, Snipes, & Calton, 2016). Among a sample of non-TGNC sexual minority women, the following lifetime prevalence of IPV was reported: 25.3% sexually victimized, 34% physically victimized, 76% psychologically victimized, and 29.3% injured because of IPV (Sutter et al., 2019). These studies show similar patterns of IPV victimization (higher levels of psychological victimization and lower levels of IPV related injury), but with some differences which may require further investigation. Taken together, this research indicates that TGNC individuals experience IPV in their relationships and trans women may be at greater risk of financial violence, sexual violence, and homicide.

IPV Services

Individuals who are experiencing or have experienced IPV may need support services. In extreme situations, emergency/temporary housing or shelter services are required to help individuals avoid IPV. However, many of these services are sex-segregated, making shelters inaccessible, and sometimes dangerous, to TGNC individuals (Cook-Daniels, 2015; Guadalupe-Diaz & Jasinski, 2017). When TGNC survivors seek mainstream women’s IPV services, they are often met with three primary patterns of responding: outright denial, only accepting those whose presentation “pass” (for TGNC women as sufficiently feminine or TGNC men having to present as women), or having a policy that is inclusive of individuals regardless of their gender (Tesch & Bekerian, 2015). Trans women have issues accessing shelter services, as they are not deemed feminine enough to pass, and trans men have issues accessing shelter services as there are fewer options for masculine presenting victims of IPV and they may be forced to present as their birth gender. For example, in a study of 380 male-to-female TGNC individuals, due to discriminatory practices and attitudes, 29% had been turned away from services (Carlson, 2016; Nemoto, Operario, & Keatley, 2005). Similarly, the 2015 NCAVP report found that 44% of survivors were denied access to shelters, and the most common reason cited (71%) was gender (NCAVP, 2016). When TGNC individuals do get access to services, they are often not culturally competent (Ard & Makadon, 2011). In a 2013 assessment of Los Angeles IPV prevention and resources, service providers reported they had little or no training for LGBT+ IPV; however, almost 50% indicated in the past year helping “sometimes” or “often” LGBT+ individuals (Ford, Slavin, Hilton, & Holt, 2013). In addition, 92% of the service providers also reported that the agency/program they worked for did not have dedicated staff for working with LGBT clients (Ford et al., 2013). Unsupportive care can lead to the re-traumatization, which can result in the TGNC individual either not seeking further support or returning to their partner (Ard & Makadon, 2011).

Mental Health in the TGNC Community

It has been fairly well documented that TGNC individuals experience higher rates of suicide, depression, anxiety, and overall psychological distress (Carmel, Hopwood, & dickey, 2014; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014; McKay, 2011; Mollon, 2012). There are a range of problems classified as anxiety disorders, with overall lifetime prevalence among non-TGNC individuals in the general U.S. population estimated around 25% (Carmel et al., 2014). It is thought that these rates are even higher among TGNC individuals (Carmel et al., 2014). Estimates of the lifetime prevalence of depression for TGNC individuals range from 50% to 67%, whereas in non-TGNC individuals in the general U.S. population, lifetime prevalence is around 9.1% (Carmel et al., 2014). TGNC individuals also are more likely to deal with suicidal ideation, with lifetime prevalence estimates ranging from 48% to 82% (Carmel et al., 2014; James et al., 2016). It is further estimated that between 21% and 41% of TGNC individuals will attempt suicide at some point during their lifetime, compared with 4.6% of non-TGNC adults in the general U.S. population (Carmel et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016). In the U.S. Trans Survey, 40% of the 27,715 respondents reported having attempted suicide at some point in their lifetime (James et al., 2016). Among those with a reported suicide attempt, 71% had attempted suicide more than once, and 46% reported three or more suicide attempts (James et al., 2016). Of the respondents who took part in the U.S. Trans Survey, 39% reported currently experiencing serious psychological distress, compared with an estimated 5% of the general U.S. population (James et al., 2016). Even the lower range estimates show that the TGNC population experience significantly higher rates of mental health issues than the general population.

Mental Health and IPV

There is significant evidence to suggest that IPV is independently associated with a variety of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, suicide attempts, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Calvete, Corral, & Estévez, 2008; Clay, 2014; Devries et al., 2013; Lagdon, Armor, & Stringer, 2014; Ouellet-Morin et al., 2015; Shorey et al., 2011). Although it has been demonstrated that women who experience IPV develop depression and anxiety at heightened rates compared with men, both have more negative mental health outcomes after experiencing IPV (Shorey et al., 2011). In a systematic review of 58 studies, Lagdon et al. (2014) found support for IPV experiences increasing adverse mental health symptomology. The most commonly associated mental health issues were depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Lagdon et al., 2014). The severity and extent of IPV exposure can impact mental health (Lagdon et al., 2014). In a longitudinal study by Ouellet-Morin et al. (2015), women who experienced IPV had an increased risk for new onset depression than their cohort peers who had not experienced abuse. Finally, in a study of college students, shame and guilt were shown to have a moderating effect on mental health symptoms among some types of IPV (Shorey et al., 2011). However, these studies were done in cisgender women and men populations.

The majority of work in relation to the larger LGBT population has focused on prevalence (e.g., Ard & Makadon, 2011; Badenes-Ribera, Frias-Navarro, Bonilla-Campos, Pons-Salvador, & Monterde-i-Bort, 2015; Langenderfer-Magruder et al., 2016) and unique features of IPV in same-sex or nonbinary relationships (e.g., Cook-Daniels, 2015; FORGE, 2017; Goodmark, 2013), with very few focusing on outcomes of IPV such as mental health (Coston, 2016). In a systematic review by Buller, Devries, Howard, and Bacchus (2014), men who have sex with men (MSM) who experienced IPV were more likely to have depressive symptoms, be HIV positive, engage in substance use, and engage in unprotected sex. In a cross-sectional study of university students, Wong et al. (2017) found that dating violence partially mediated the effect of sexual minority status on mental health. In a longitudinal study of LGBT youth, those who experienced IPV were found to be at greater risk for future depression and anxiety (Reuter, Newcomb, Whitton, & Mustanski, 2017). Although the mental health disparities for the TGNC population are well documented (e.g., Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014; McKay, 2011; Mollon, 2012), there is extremely limited work linking mental health in TGNC populations to IPV.

In summary, rates of lifetime IPV prevalence for TGNC individuals are reported between 31.3% and 50%, which exceed the 10% of non-TGNC men and are similar to or exceed the 33% of non-TGNC women who experience IPV (Black et al., 2011; Brown & Herman, 2015; Yerke & DeFeo, 2016). Trans survivors of IPV are three times more likely than non-TGNC survivors to experience stalking, sexual violence, and financial violence (NCAVP, 2016). Individuals who are experiencing or have experienced IPV may need support services. When TGNC survivors seek mainstream women’s IPV services, they are often met with the following: outright denial, only accepting those whose presentation is appropriately gendered, or an inclusive policy regardless of gender (Tesch & Bekerian, 2015). It is also well documented that TGNC individuals experience higher rates of suicide, depression, anxiety, and overall psychological distress (Carmel et al., 2014; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014; McKay, 2011; Mollon, 2012). There is significant evidence to suggest that IPV is independently associated with a variety of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, suicide attempts, and PTSD symptoms (Calvete et al., 2008; Clay, 2014; Devries et al., 2013; Lagdon et al., 2014; Ouellet-Morin et al., 2015; Shorey et al., 2011). The majority of work regarding IPV in relation to the larger LGBT population has focused on prevalence (e.g., Ard & Makadon, 2011; Badenes-Ribera et al., 2015; Langenderfer-Magruder et al., 2016) and unique features of IPV in same-sex or nonbinary relationships (e.g., Cook-Daniels, 2015; FORGE, 2017; Goodmark, 2013), with very few focusing on outcomes of IPV such as mental health (Coston, 2016). Although the mental health disparities for the TGNC population are well documented (e.g., Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014; McKay, 2011; Mollon, 2012), there is extremely limited work linking mental health in TGNC populations to IPV.

The Current Study

The purpose of the current study is to explore the relationships between types of IPV experienced (psychological aggression, sexual coercion, physical assault, and assault with injury) and various indices of mental health (depression, anxiety, and satisfaction with life) in TGNC individuals. Very little research has examined IPV in TGNC populations, and the extant research has generally tended to be qualitative in nature. Based on past evidence that IPV is associated with negative mental health outcomes in the general population (Calvete et al., 2008; Lagdon et al., 2014; Ouellet-Morin et al., 2015; Shorey et al., 2011), it is hypothesized that increased experiences of IPV will be associated with reduced mental health in TGNC individuals.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 78) were recruited via convenience sampling to complete this national, online survey on TGNC adults. To be included, participants had to be at least 18 years old and self-identify as a transgender, gender nonconforming, or some other non-cisgender gender. Participants had a mean age of 29.6 years (SD = 10.46 years). The sample included 26 trans men (33.3%), 29 trans women (37.2%), and 23 various self-identified gender minority identities (29.5%). Information about sexual orientation, racial/ethnic identity, social class, education, and relationship status are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information.

| Demographics | % |

|---|---|

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 15.4 |

| Gay/lesbian | 12.8 |

| Bisexual | 15.4 |

| Queer | 41.0 |

| “Other” | 15.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White/European American (non-Latino) | 61.5 |

| Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander | 10.3 |

| Black/African American (non-Latino) | 9.0 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 2.6 |

| American Indian/Native American | 1.3 |

| Multiracial/Multiethnic | 12.8 |

| Social class | |

| Upper class | 1.3 |

| Upper middle class | 30.8 |

| Lower middle class | 34.6 |

| Working class | 12.8 |

| Lower class | 20.5 |

| Education | |

| High school/GED | 6.4 |

| Some college (no degree) | 35.9 |

| 2-year/technical degree | 7.7 |

| 4-year college degree | 34.6 |

| Master’s degree | 14.1 |

| Doctorate degree | 1.3 |

| Relationship status | |

| Long-term relationship (>12 months) with one person | 38.5 |

| New relationship (<12 months) with one person | 11.5 |

| Dating/in a relationship with more than one person | 11.5 |

| Not currently dating or in a relationship | 38.5 |

Note. GED = General Educational Development.

Measures

Participants completed the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist–25 (HSCL-25; Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, 1974) to assess depression and anxiety, the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) to measure life satisfaction, and the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale short-form (Straus & Douglas, 2004) to measure experiences with IPV. Demographic information was gathered via a researcher-created questionnaire.

HSCL-25.

Depression and anxiety symptoms were evaluated using the HSCL-25 (Derogatis et al., 1974). The HSCL-25 is a self-report measure consisting of 15 items for depression and 10 items for anxiety, for a total of 25 items. These items assess how much over the course of the previous week an individual was distressed or bothered by their symptoms. Responses to these items ranged from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely), with higher scores signaling greater symptoms. For each subscale, a clinical cutoff of 1.75 is used to identify significant symptoms (Sandanger et al., 1999). Validity of the HSCL-25 has been demonstrated by correlations with medical doctors’ assessment of psychological distress and additional measures of emotional symptoms (Hesbacher, Rickels, Morris, Newman, & Rosenfeld, 1980).

SWLS.

The SWLS is a five-item self-report measure of global subjective well-being without specific time parameters. There are five possible response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Each item looks at satisfaction from a different domain to create an overall satisfaction score (Diener et al., 1985). A score of 5 to 9 is considered extremely dissatisfied, a score of 10 to 14 is dissatisfied, 15 to 19 is slightly dissatisfied, 20 to 24 is average, 25 to 29 is considered a high score, and 30 to 35 is highly satisfied (Pavot & Diener, 2013). The total scale has a high reported internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .87; Diener et al., 1985).

Revised Conflict Tactics Scale short-form (CTS2S).

The CTS2S is a 10-item measure that assesses one’s experiences as a target of IPV (Straus & Douglas, 2004). The items assess how often a participant’s partner behaved a certain way, and these items corresponded to four types of IPV: psychological aggression, sexual coercion, physical assault, and assault with injury. There were eight response options. Responses 1 (“once in the past year”) to 6 (“more than 20 times in the past year”) indicate abuse in the past year, while response 7 (“not in the past year, but it did happen before”) suggests lifetime prevalence, and a response of 8 (“this has never happened”) suggests a lack of abuse. For this study, a response of 1 to 7 was recoded as 1 (“lifetime prevalence”), while a response of 8 was recoded as 0 (“absence”). A summative score was then created for each category of IPV, resulting in scores of 0 (“no IPV”), 1, or 2. This scale has been used widely used in IPV literature (e.g., Edwards, Dixon, Gidycz, & Desai, 2014; Hines & Douglas, 2016; Lyons, Bell, Frechette, & Romano, 2015; Udo, Lewis, Tobin, & Ickovics, 2016).

Procedure

Online forums and groups were used to recruit participants for this study. With open groups and forums, study information and recruitment details were posted directly to community message boards. For closed groups, information was sent to the moderators for posting. Details about the study and information about recruitment was also emailed to both regional and national LGBT+ organizations. Screening of interested parties was done by the research coordinator to determine study eligibility. A link to the study survey and code was emailed to those who met the study criteria. Participant data were deleted from the survey software if any of the following criteria was met: there was an impossible response pattern (e.g., selecting the same response for every single item), participants did not correctly respond to four out of six (66.6%) of the validation questions, or if there were indications of false responding or computer responding (e.g., the survey was completed too quickly or took too long to complete). The specific number of deleted responses is unknown, as this was a requisite automatic process by the host institution’s information security officer to prevent the fraudulent use of state funds. Inclusion criteria for the current study required that the participant be at least 18 years old and self-identified a gender minority. Individuals were not allowed to participate if they did not meet inclusion criteria, provided illogical responses, or appeared to be a computer program. Participants were given a US$15 electronic Amazon.com gift card as compensation for completing this study. The study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from participants.

Data Analysis Plan

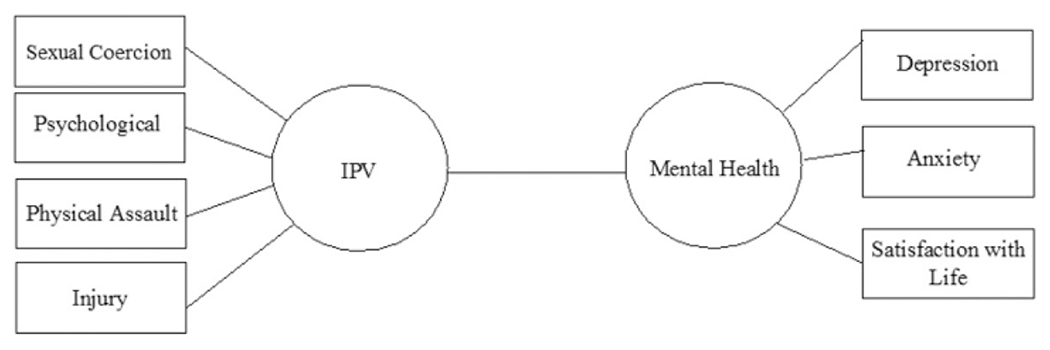

First, rates of IPV in the sample were obtained. Second, descriptive statistics for the mental health variables were calculated and presented. Third, a bivariate correlation table showing the relationships between all primary variables in the study were computed. Finally, to assess which forms of IPV were most associated with which aspects of mental health, a canonical correlation analysis was performed (Figure 1). A canonical correlation analysis evaluates the association between two sets of variables, which in this study were IPV and mental health. The overlap from both sets of variables combines to create a canonical correlation coefficient (r) indexing the size of the relationship between the two variable sets. For each canonical correlation analysis, a number of canonical correlations are generated equal to the number of variables in the smaller of the two sets (in this case, mental health with three variables). Typically, the first canonical correlation is the largest and most significant. As a result, only the first canonical correlation was interpreted, although information on the second and third canonical correlations is presented for reference. All statistical tests were run using IBM SPSS 24 statistics software.

Figure 1.

Canonical correlation model of IPV and mental health. Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

Results

IPV and Mental Health Levels

IPV was examined in terms of the lifetime prevalence of four subcategories (psychological aggression, sexual coercion, physical assault, and assault with injury). Of the four types of IPV, 70.6% of the sample reported experiencing psychological abuse, 32.1% sexual abuse, 42.3% physical abuse, and 29.4% reported experiencing assault with injury. Three mental health outcomes were examined in this study—depression, anxiety, and satisfaction with life. For depression and anxiety, a clinical cutoff of 1.75 is used to identify significant symptoms, with a minimum score of zero and maximum score of three (Sandanger et al., 1999). For anxiety, the mean score was 0.94 (SD = 0.67), with 69 (88.5%) participants below the clinical cutoff of 1.75. For depression, the mean score was 1.16 (SD = 0.74), with 63 (80.8%) participants below the clinical cutoff of 1.75. For the SWLS, a higher score indicates greater satisfaction. Possible scores range from 5 to 35. The mean score for satisfaction with life was 17.56 (SD = 7.68), meaning that the average was “slightly dissatisfied.” Out of all the participants, the majority (60.3%) were slightly to extremely dissatisfied.

Correlation Matrix

A correlation table was calculated showing all of the bivariate relationships among variables in the current study (Table 2). All four types of IPV were significantly and positively associated with anxiety, and all but physical abuse was significantly associated with depression. None of the four types of IPV was associated with satisfaction with life.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Between IPV and Mental Health.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Psychological abuse | |||||||

| 2. | Sexual abuse | .571** | ||||||

| 3. | Physical abuse | .736** | .658** | |||||

| 4. | Injury | .646** | .695** | .811** | ||||

| 5. | Anxiety | .396** | .457** | .451** | .469** | |||

| 6. | Depression | .245* | .227* | .210 | .270* | .730** | ||

| 7. | Satisfaction with life | −.011 | .009 | −.066 | −.005 | −.386** | −.551** |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed).

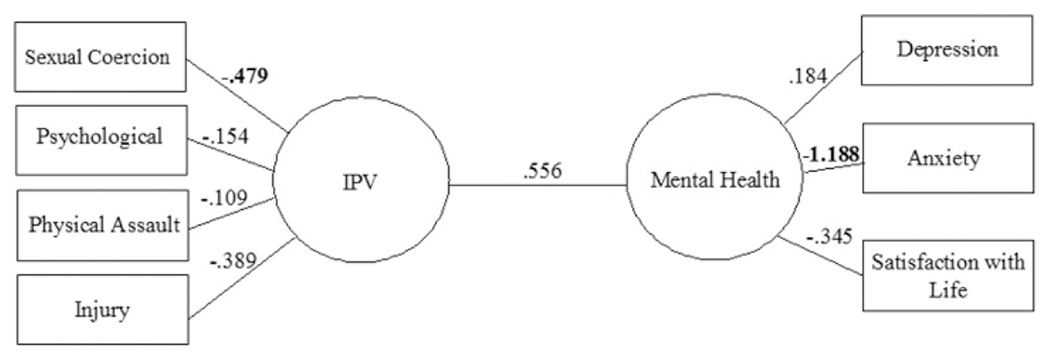

Canonical Correlation Analysis

The first canonical correlation examining the association between experiences with IPV and mental health was r = .556 (30.9% overlapping variance), λ = .641, χ2(12) = 32.44, p = .001, a large-sized effect. Standardized canonical coefficients were used to examine the relative contribution of each variable to the overall canonical correlations (Table 3). In the first canonical correlation (Figure 2), the standardized canonical coefficients for IPV showed that sexual coercion (−0.479) followed in magnitude by injury (−0.389), psychological aggression (−0.154), and physical assault (−0.109). Because the coefficient reflecting sexual coercion was above the conventional cutoff of .40, this will be focused on for interpretation. For the mental health variables, anxiety loaded most highly (−1.188), followed by satisfaction with life (−0.345) and depression (0.184). This pattern of shared variance suggests that TGNC individuals experienced higher levels of anxiety symptoms when they had experienced sexual coercion.

Table 3.

Standardized Canonical Coefficients of Correlations One, Two, and Three.

| Connonical Correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intimate partner violence | _ 1 _ | _ 2 _ | _ 3 _ |

| Sexual coercion | −0.479 | −0.096 | −1.262 |

| Psychological aggression | −0.154 | 0.869 | 0.630 |

| Physical assault | −0.109 | −1.892 | 0.499 |

| Injury | −0.389 | 1.145 | 0.267 |

| Mental health | _ 1 _ | _ 2 _ | _ 3 _ |

| Depression | 0.184 | 1.463 | 0.670 |

| Anxiety | −1.188 | −0.772 | −0.367 |

| Satisfaction with life | −0.345 | 0.924 | −0.682 |

Note. Coefficients in bold tended to cluster together and were focused on interpretation.

Figure 2.

Standardized canonical loadings for the first canonical correlation with loadings in bold that surpassed the .40 cutoff. Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

The second canonical correlation was r = .263 (6.92% overlapping variance), λ = .928, χ2(6) = 5.492, p = .482; and the third was r = .058 (0.34% overlapping variance), λ = .997, χ2(2) = 0.249, p = .883. The standardized canonical coefficients appear in Table 3 for reference.

Discussion

Out of 78 participants, 56 (71.8%) reported experiencing at least one form of IPV in their lifetime. The most common type was psychological abuse (70.6%), followed by physical abuse (42.3%), followed by sexual abuse (32.1%), with injury being the least reported (29.4%). The overall rate is slightly higher than found in other studies with LGBTQ and TGNC samples (31.3%-54%; Brown & Herman, 2015; James et al., 2016; Yerke & DeFeo, 2016), which may be a result of the high rate of reported psychological abuse. Further investigation needs to be done to determine whether TGNC individuals are more likely to experience psychological abuse, or whether unique aspects of IPV victimization are captured by the psychological abuse subscale (i.e., threats of outing, misgendering, undermining the TGNC individual’s gender and expression).

Depression, anxiety, and satisfaction with life were measured as indicators of mental health. Of note, 80.8% of participants fell below cutoff for clinically significant depression symptomology. This is well below the estimate that 50% to 67% of TGNC individuals will experience depression at some point in their lifetime (Carmel et al., 2014). Similarly, 88.5% of participants were below the cutoff for clinically significant anxiety symptoms. It is estimated that a quarter of the general population will experience some form of anxiety and that the rate among TGNC individuals will be higher (Carmel et al., 2014). However, these estimates come primarily from self-report measures, which may not meet the threshold for clinical significance. In addition, the HSCL-25 only captures symptoms from the week prior to when it was taken and does not reflect whether a person has ever experienced depression or anxiety in their lifetime. Thus, it is possible that some participants who have struggled with clinically significant depression or anxiety in the past did not meet clinical cutoff for these diagnoses at the time they completed the survey.

Although participants did not report high levels of depression and anxiety symptomology, 60.3% of participants were slightly to extremely dissatisfied with their lives. There are several possible explanations for this. First, the SWLS measure is not bound by the same timeframe considerations as the HSCL-25 is for anxiety and depression. Second, this reflects prior research that indicates satisfaction with life is related to but independent of positive emotions and/or a lack of negative emotions (Diener, Oishi, & Lucas, 2003). Because satisfaction with life entails a person’s cognitive evaluation of life, it can differ from recent emotional experiences. For example, it is possible for people to experience depression when aspects of their lives are objectively good (e.g., secure job, supportive family).

Third, the fact that few participants had clinically significant depression and anxiety despite much higher levels of dissatisfaction with life may reflect a level of resilience within this population. Prior research suggests factors such as effective coping skills and social support from LGBTQ communities (Bariola et al., 2015; Breslow et al., 2015) can foster resilience in the face of life stressors. There are also many formative experiences for TGNC individuals which may operate as risk or resilience factors for later experiences including IPV. A common protective factor is social support (McConnell, Birkett, & Mustanski, 2015; Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010), and one’s family of origin can be one support network. Family acceptance for LGBT adolescence has been linked to greater self-esteem and general health, and it protects against depression, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation (Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010). Among respondents of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 60% who were out to the immediate family they grew up with reported that they had supportive family members (James et al., 2016). However, 10% reported that an immediate family member had behaved violently toward them because they were transgender, and 15% had run away or been kicked out of the house because they were transgender (James et al., 2016). Half of all respondents who were out to their family had experienced at least one form of rejection from their immediate family (James et al., 2016). In the 2011 Transgender Discrimination Survey, 57% reported experiencing some form of family rejection, but 88% of respondents’ family bonds were as strong or they were able to maintain most of their family bonds after coming out (Grant et al., 2011). Although it was common—half or more—to experience some form of family rejection, 60% to 88% of TGNC individuals had supportive family members and strong family bonds (Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016). Peers can be another early form of social support. In school, of respondents to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey who were out or were perceived as transgender in K-12, 54% were verbally harassed and 24% were physically attacked (James et al., 2016). Reports of physical assault (35% vs. 24%) were down from the 2011 Transgender Discrimination Survey, yet more respondents in 2015 reported having to leave school than in 2011 because of mistreatment (17% vs. 15%; Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016). However, in the 2015 survey, 56% of participants whose classmates knew they were transgender reported that their classmates’ level of support was either “supportive” or “very supportive,” and only 5% reported their classmates were “unsupportive” or “very unsupportive” (James et al., 2016). While many TGNC youth experience some form of harassment in school, 56% of TGNC individuals had supportive peers (James et al., 2016). This suggests the families and school peers of TGNC individuals, for some, may be a good source of social support. TGNC individuals may develop ways of coping with negative circumstances that mitigate their impact on mental health.

In the correlation matrix, none of the four types of IPV was associated with satisfaction with life; but all four types were associated with anxiety, and all but physical abuse was significantly associated with depression. As none of the four types of IPV was associated with satisfaction with life, this suggests that other factors may have weighed more heavily into current satisfaction with life. Given the many potential stressors that TGNC population may face, it is possible that a host of other variables, such as stigma toward TGNC people and lack of access to TGNC-affirming medical treatments (e.g., hormones), are impacting their satisfaction with life. In addition, because IPV was measured in terms of its lifetime prevalence, future studies that use more current measures of IPV may show greater relationships to current life satisfaction. Furthermore, factors such as the severity, extent, and time since the IPV experience may all impact individual outcomes. The four types of IPV being significantly associated with anxiety and depression—except for physical abuse and depression—support existing literature that IPV is associated with negative mental health outcomes (Buller et al., 2014; Calvete et al., 2008; Lagdon et al., 2014; Ouellet-Morin et al., 2015; Reuter et al., 2017; Shorey et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2017).

The first canonical correlation showed an overall large-sized association between experiences of IPV and mental health. In demonstrating the overall relationship, this suggests IPV is one source or contributor to the mental health disparities shown in this population (Carmel et al., 2014; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014; McKay, 2011; Mollon, 2012) and identifies TGNC individuals who have experienced IPV of potentially being at risk for future mental health issues. Of the types of IPV, sexual coercion loaded most highly, followed by injury, psychological aggression, and physical assault. For the mental health variables, anxiety was the largest in magnitude, followed by satisfaction with life and depression. This pattern of shared variance suggests that TGNC individuals reported higher levels of anxiety when they had experienced sexual coercion in the context of an intimate relationship. Further research investigating the nature of the relationship between anxiety and sexual coercion is necessary, as there may be some TGNC specific issues contributing to this relationship. For example, violating boundaries is a common tactic in TGNC IPV (Cook-Daniels, 2015); this can include not respecting wishes regarding what terminology to use in regard to the TGNC individual’s body, touching parts of the body that are deemed off limits, and/or fetishizing the body.

Implications for Research and Practice

Understanding the relationship between IPV and mental health in the TGNC community can help inform both how service providers screen for IPV and tailor services to meet the needs of this population. The four types of IPV assessed (psychological, sexual coercion, physical abuse, and injury) were associated with anxiety, and all but physical abuse was significantly associated with depression. Because of the relationship between IPV and mental health—particularly between sexual victimization and anxiety—TGNC individuals screening positive for or seeking services for IPV might also be considered for referral to a mental health professional. Service providers at sexual assault hotlines, domestic violence shelters, and domestic violence hotlines may be the first to interact with TGNC individuals as they seek help for IPV. If a domestic violence center or hotline does not have a trained LGBTQ advocate on staff, it may be helpful to consult with and/or refer TGNC survivors to a local LGBTQ anti-violence organization or advocacy center that is knowledgeable about TGNC-specific needs and affirming practices. For example, the National LGBTQ Institute on IPV provides resources, consultation, and training on LGBTQ IPV to mainstream domestic violence organizations (National LGBTQ Institute on IPV, 2017).

For TGNC individuals who experience IPV, it is important that these referrals allow them to access sensitive and culturally competent care. Although some aspects of IPV are similar, there may be unique characteristics of IPV for TGNC individuals (Cook-Daniels, 2015; FORGE, 2017). In addition, it is necessary to consider the historic relationship between TGNC individuals and mental health providers. TGNC individuals have been pathologized in psychology and medicine (Bauer et al., 2009; Stroumsa, 2014; White Hughto, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015). Because of the negative mental health consequence of IPV, these individuals may be in greater need of mental health services but also may be more hesitant to seek them out, given the historical and current pathologizing in mental health services of TGNC individuals. However, TGNC individuals should not only have access to mental health care services, but access to quality and culturally competent mental health care. TGNC survivors may feel more comfortable speaking about their mental health needs with other members of the TGNC community, and they may seek referrals for mental health providers who have been clearly established as TGNC-affirming. Local LGBTQ anti-violence organizations and advocacy centers can be invaluable in making these connections.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to the present study which suggest directions for future research. The sample size, albeit including some diversity, was slightly small, which limits the generalizability of the results. Some researchers have suggested using 20 to 60 times the number of cases as variable for the analysis (Barcikowski & Stevens, 1975). So, while with the current sample size a significant result was detected, a greater sample size may be beneficial. This implies a replication with a larger sample of the findings is warranted.

Another limitation includes the measures chosen for measuring the IPV experiences. While psychological aggression, sexual coercion, physical assault, and injury are all present features in IPV in the TGNC community, those measures mirror the dominant IPV narrative and may not capture the unique TGNC experiences (e.g., outing, gaslighting, and identity threat). Also, this measure assumes a dyadic relation, which may not necessarily be reflective of an individual’s relationship formation (11.5% of the sample stated that they were dating/in a relationship with more than one person). Moreover, the CTS2 has been criticized for measuring violence “out of context,” insomuch that it does not assess the subjective or symbolic meaning of a violent act within a relationship and only surveys one partner (Shrader, 2001). The IPV measure also collapses all experiences of IPV into limited categories: has never happened, has happened in the past year, or has occurred in the lifetime of the individual. A couple who experiences IPV on a daily basis versus a couple who has a few experiences a month would score the same, but have very different outcomes.

A further limitation is that this study did not ask when the IPV occurred/was occurring. By aggregating the variable into lifetime prevalence, and not asking about when it occurred in relation to transition, there might be some valuable information missing about the TGNC community. Are individuals experiencing higher rates of IPV prior to coming out, right after coming out, early in transition, or later in transition? In other words, at what point in their gender formation and development are they at most risk for experiencing IPV? A related issue might be that of “passing” and “visibility.” The notion of “passing” is that the gender expression and/or presentation is read as cisgender. There is evidence indicating that the less an individual passes—or the less their identity conforms to hegemonic social norms—the more likely they are to be targets of violence (Herek, 1992, 1995; Serano, 2009). This suggests that a future direction is investigating the ways in which psychological abuse in IPV may encompass use of emotional/control tactics specifically around romantic partners’ attempts at forcing their TGNC partner to fit neatly into the traditional gender binary. Given the high rates of IPV in the TGNC community, knowing if there is a stage at which a TGNC individual might be more vulnerable to experiencing various types of IPV and how well they are perceived to pass with regard to gender binaries may allow for more targeted IPV screening, intervention, and support at different stages of transition or across diverse gender presentations.

Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the relationship between experiences of IPV (psychological aggression, sexual coercion, physical assault, and assault with injury) and mental health (depression, anxiety, and satisfaction with life) in a TGNC population. As with cisgender population, depression and anxiety were found to be significantly correlated with experiences of IPV. However, there are many unique features of IPV for TGNC individuals that require further investigation (e.g., outing, gaslighting, and identity threat), as well as how TGNC individuals access services. In the sample, with 32.1% having experienced sexual abuse, 70.6% having experienced psychological abuse, 42.3% having experienced physical abuse, and 29.4% having experienced injury (which are comparable rates to other studies), it is clear IPV in TGNC populations is a pervasive problem. This is an important area for research, and studies such as this can help with the designing of future interventions aimed at improving the lives of those who have experienced IPV in the TGNC community.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The survey software for this study was funded by award number UL1TR000058 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Biographies

Author Biographies

Richard S. Henry, MA, is a 2nd year graduate student in the Health Psychology program at Virginia Commonwealth University. His work focuses on health disaparities, aging, disability, and underserved populations.

Paul B. Perrin, PhD, is an associate professor and the director of the Health Psychology Doctoral Program at Virginia Commonwealth University. He received his PhD in Counseling Psychology from the University of Florida, and his research area is social justice in health.

Bethany M. Coston, PhD, is an assistant professor of health and queer studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, is a sociologically-trained activist scholar who has spent time in the midwest and on the east coast educating, protesting, and participating in research on the making of sexual identities, violence, health and wellness and community-based organizing. She spends most of their time with grassroots organizations/groups that work to end LGBTQ+ intimate partner violence and make victims’/survivors’ lives better in the process. She is a former pre-doctoral population health fellow with the National LGBT Health Education Center at Fenway Health and currently a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation New Connections scholar.

Jenna M. Calton, PhD, completed undergraduate degrees in psychology and women’s studies at The University of Florida. She earned her PhD in clinical psychology from George Mason University. She is currently a post-doctoral fellow at The Tree House Child Advocacy Center of Montgomery County, Maryland, where she delivers evidence-based trauma-focused treatment to children and adolescents who have experienced trauma. Her research interests include intimate partner violence (IPV) prevention and intervention efforts, IPV survivors’ perceptions of procedural and distributive justice, as well as barriers to help-seeking for survivors of intimate partner violence.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ard KL, & Makadon HJ (2011). Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 630–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenes-Ribera L, Frias-Navarro D, Bonilla-Campos A, Pons-Salvador G, & Monterde-i-Bort H (2015). Intimate partner violence in self-identified lesbians: A Meta-analysis of its prevalence. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(1), 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Barcikowski R, & Stevens JP (1975). A Monte Carlo study of the stability of canonical correlations, canonical weights, and canonical variate-variable correlations. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 10, 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariola E, Lyons A, Leonard W, Pitts M, Badcock P, & Couch M (2015). Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with psychological distress and resilience among transgender individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 2109–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, Hammond R, Travers R, Kaay M, Hohenadel KM, & Boyce M (2009). “I don’t think this is theoretical; This is our lives”: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 20, 348–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, & Stevens MR (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/NISVS_Report2010-a.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, & Cesaretti C (2001). Spirituality, transgender identity, and coming out. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 26, 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow AS, Brewster ME, Velez BL, Wong S, Geiger E, & Soderstrom B (2015). Resilience and collective action: Exploring buffers against minority stress for transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2, 253–265. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TNT, & Herman JL (2015). Intimate partner violence and sexual abuse among LGBT people: A review of existing research. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Intimate-Partner-Violence-and-Sexual-Abuse-among-LGBT-People.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Buller AM, Devries KM, Howard LM, & Bacchus LJ (2014). Associations between intimate partner violence and health among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 11(3), e1001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calton JM, Cattaneo LB, & Gebhard KT (2016). Barriers to help seeking for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer survivors of intimate partner violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17, 585–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Corral S, & Estévez A (2008). Coping as a mediator and moderator between intimate partner violence and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Violence against Women, 14, 886–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R (2016). Shelter response to intimate partner violence in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community (Master of social work clinical research papers). Retrieved from http://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/563

- Carmel T, Hopwood R, & dickey l. m (2014). Mental health concerns. In Erickson-Schroth L (Ed.), Trans bodies, trans selves: A resource for the transgender community (pp. 305–332). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clay RA (2014). Suicide and intimate partner violence. Monitor on Psychology, 45, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Daniels L (2015). Intimate partner violence in transgender couples: “Power and control” in a specific cultural context. Partner Abuse, 6, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Coston BM (2016). Breaking the silence: Lesbian, gay, and bisexual experiences of intimate partner violence and health-related effects. Eastern Michigan University Equality Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.emich.edu/equality/research/research-reports.php [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, & Covi L (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, Child JC, Falder G, Petzold M, & Watts CH (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine, 10, e1001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Oishi S, & Lucas RE (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan C, & Barnes R (2019). Domestic violence and abuse in lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or transgender (LGB and/or T) relationships. Sexualities. , 22(5-6), 741–750. doi: 10.1177/1363460716681491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Dixon KJ, Gidycz CA, & Desai AD (2014). Family-of-origin violence and college men’s reports of intimate partner violence perpetration in adolescence and young adulthood: The role of maladaptive interpersonal patterns. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15, 234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, & Brown TNT (2016). How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute. Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many-Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, Slavin T, Hilton KL, & Holt SL (2013). Intimate partner violence prevention services and resources in Los Angeles: Issues, needs, and challenges for assisting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients. Health Promotion Practice, 14, 841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORGE. (2017). Our mission and history. Retrieved from http://forge-forward.org/about/our-mission-and-history/

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Simoni JM, Kim HJ, Lehavot K, Walters KL, Yang J, … Muraco A (2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? The Williams Institute. Retrieved from https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg-Looney LD, Perrin PB, Snipes DJ, & Calton JM (2016). Coping styles used by sexual minority men who experience intimate partner violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 3687–3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodmark L (2013). Transgender people, intimate partner abuse, and the legal system. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 48(1), 51–104. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, & Keisling M (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Retrieved from http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Guadalupe-Diaz XL, & Jasinski J (2017). “I wasn’t a priority, I wasn’t a victim”: Challenges in help seeking for transgender survivors of intimate partner violence. Violence against Women, 23, 772–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (1992). The social context of hate crimes: Notes on cultural heterosexism. In Herek GM & Berrill KT (Eds.), Hate crimes: Confronting violence against lesbians and gay men (pp. 89–104). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (1995). Psychological heterosexism in the United States. In D’ Augelli AR & Patterson CJ (Eds.), Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities over the lifespan: Psychological perspectives (pp. 321–324). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hesbacher PT, Rickels K, Morris RJ, Newman H, & Rosenfeld H (1980). Psychiatric illness in family practice. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 41(1), 6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, & Douglas EM (2016). Relative influence of various forms of partner violence on the health of male victims: Study of a help seeking sample. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(1), 3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. (2018). Violence against the transgender community in 2018. Retrieved from https://www.hrc.org/resources/violence-against-the-transgender-community-in-2018

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, & Anafi M (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. Retrieved from http://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS%20Full%20Report%20-%20FINAL%201.6.17.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lagdon S, Armour C, & Stringer M (2014). Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenderfer-Magruder L, Whitfield DL, Walls NE, Kattari SK, & Ramos D (2016). Experiences of intimate partner violence and subsequent police reporting among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer adults in Colorado: Comparing rates of cisgender and transgender victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31, 855–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J, Bell T, Frechette S, & Romano E (2015). Child-to-parent violence: Frequency and family correlates. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 729–742. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell EA, Birkett MA, & Mustanski B (2015). Typologies of social support and associations with mental health outcomes among LGBT youth. LGBT Health, 2, 55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay B (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health issues, disparities, and information resources. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 30, 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollon L (2012). The forgotten minorities: Health disparities of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs. (2016). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and HIV-Affected Intimate Partner Violence in 2015. Retrieved from http://avp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2015_ncavp_lgbtq-ipvreport.pdf

- National LGBTQ Institute on IPV. (2017, September21). About us. Retrieved from http://lgbtqipv.org/about-us/

- Nemoto T, Operario D, & Keatley J (2005). Health and social services for male-to-female transgender persons of color in San Francisco. International Journal of Transgenderism, 8(2/3), 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet-Morin I, Fisher HL, York-Smith M, Fincham-Campbell S, Moffitt TE, & Arseneault L (2015). Intimate partner violence and new-onset depression: A longitudinal study of women’s childhood and adult histories of abuse. Depression and Anxiety, 32, 316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, & Diener E (2013). The satisfaction with life scale (SWL). Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Science. Retrieved from http://www.midss.org/sites/default/files/understanding_swls_scores.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Porter KE, Ronneberg CR, & Witten TM (2013). Religious affiliation and successful aging among transgender older adults: Findings from the Trans MetLife Survey. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging, 25, 112–138. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter TR, Newcomb ME, Whitton SW, & Mustanski B (2017). Intimate partner violence victimization in LGBT young adults: Demographic differences and associations with health behaviors. Psychology of Violence, 7, 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, & Sanchez J (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23, 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandanger I, Moum T, Ingebrigtsen G, Sørensen T, Dalgard OS, & Bruusgaard D (1999). The meaning and significance of caseness: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview II. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34(1), 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serano J (2009). Whipping girl: A transsexual woman on sexism and the scapegoating of femininity. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Sherman AE, Kivisto AJ, Elkins SR, Rhatigan DL, & Moore TM (2011). Gender differences in depression and anxiety among victims of intimate partner violence: The moderating effect of shame proneness. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 1834–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrader E (2001). Methodologies to measure the gender dimensions of crime and violence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/19590 [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, & Douglas EM (2004). A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims, 19, 507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroumsa D (2014). The state of transgender health care: Policy, law, and medical frameworks. American Journal of Public Health, 104(3), e31–e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter M, Rabinovitch AE, Trujillo MA, Perrin PB, Goldberg-Looney L, Coston BM, & Calton JM (2019). Patterns of intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization among sexual minority women: A latent class analysis. Violence against Women, 25(5), 572–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesch PB, & Bekerian DA (2015). Hidden in the margins: A qualitative examination of what professionals in the domestic violence field know about transgender domestic violence. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 27, 391–411. [Google Scholar]

- Udo I, Lewis J, Tobin J, & Ickovics J (2016). Intimate partner victimization and health risk behaviors among pregnant adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 1457–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto J, Reisner S, & Pachankis J (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten TM (2003). Transgender aging: An emerging population and an emerging need. Sexologies, 12, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Witten TM (2016). The intersectional challenges of aging and being a gender nonconforming adult. Generations, 40(2), 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wong J, Choi E, Lo H, Wong W, Chio J, Choi A, & Fong D (2017). Dating violence, quality of life and mental health in sexual minority populations: A path analysis. Quality of Life Research, 26, 959–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerke AF, & DeFeo J (2016). Redefining intimate partner violence beyond the binary to include transgender people. Journal of Family Violence, 31, 975–979. [Google Scholar]