Introduction

Pretibial myxedema (PTM) is a dermatological manifestation of autoimmune thyroiditis, most commonly Graves' disease, due to intradermal deposition of mucin.1 PTM has a prevalence of 1% to 5% in patients with Graves' disease, and it is more prevalent (25%) in those with exophthalmos.2 Orbital fibroblasts and the pretibial dermis share antigenic sites that underlie the autoimmune pathophysiology that causes Graves' disease.1 While no cure exists for the orbitopathy or pretibial myxedema associated with Graves' disease, several effective treatments have been studied, such as topical and intralesional corticosteroids,2 combined pentoxifylline and intralesional triamcinolone,1 rituximab, plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin.2 Additionally, intralesional octreotide, which has insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) antagonist properties, has demonstrated a beneficial effect on PTM, likely suppressing hyaluronic acid secretion by fibroblasts through IGF-1 inhibition.3 These therapies have been shown to at least partially alleviate Graves' ophthalmopathy and/or PTM. However, current definitive treatments are lacking and can cause dose-limiting adverse reactions.4

Recently, teprotumumab, a human monoclonal antibody inhibitor of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R), has been shown to reduce proptosis in patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy.5 One case has been reported in which a patient underwent treatment of Graves' associated ophthalmopathy with teprotumumab and had coincidental improvement in her PTM.6 However, there is little data on its long-term efficacy, and it is not considered standard of care. We present a patient with treatment-refractory PTM who had improved outcomes with teprotumumab therapy.

Case report

This patient is a 50-year-old white woman with a past medical history of Graves' disease with significant extrathyroidal manifestations including ophthalmopathy, acropachy, and biopsy-proven PTM predominately affecting her distal anterior and lateral legs. Past treatments include topical and intralesional corticosteroids, compression wraps, intravenous immunoglobulin methotrexate, glucocorticoids, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and intralesional hyaluronidase, with minimal improvement.

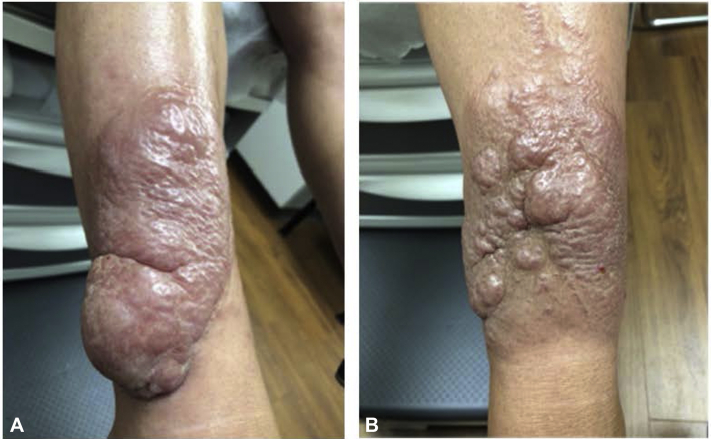

The patient was transferred to our care in March 2020. At that time, she reported worsening plaques on her lower extremities as well as pain and weakness in her legs. Physical examination showed multilobular, red-brown infiltrated plaques to bilateral anterior distal lower extremities (Fig 1). Laboratory findings at that time were significant for an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 23 mm/hr, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.27 mIU/ml, free thyroxine of 1.38 ug/dL, and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin of 3.9 IU/ml.

Fig 1.

Right (A) and left (B) lower portions of extremity before teprotumumab therapy.

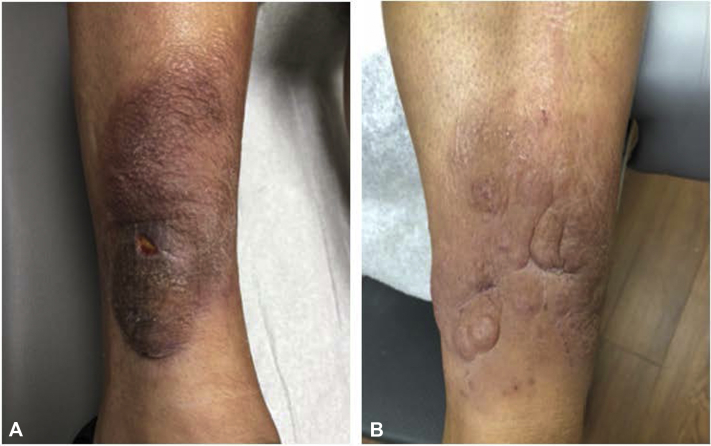

She was subsequently started on levothyroxine 75 mcg, methimazole 5 mg, and pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times per day per endocrinology recommendations. Methimazole was continued despite the patient's euthyroid state due to her persistent elevation in thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin. In consultation with Mayo Clinic, she was started on intravenous infusions of teprotumumab at 10 mg/kg/dose for 1 dose, then 20 mg/kg/dose for the remaining doses. A total of 8 infusions were given every 3 weeks. After completing her first infusion of teprotumumab, the patient had improvement of PTM with softening and decreased size of plaques on her lower extremities, which continued to reduce throughout treatment (Fig 2). During treatment, the more indurated lesions softened and formed small mucin-containing bullae. Incision and drainage (I&D) of these bullae was performed following the fifth, sixth, and eighth teprotumumab infusion, as well as 1 month posttreatment. The lesions were stable at 2 months posttreatment. However, by 5 months posttreatment, the lesions on her lower extremities were increasing in size. She is maintained on pentoxifylline and methimazole daily. The patient initially smoked 1 pack of cigarettes per day and tapered during treatment. She quit smoking after her sixth dose of teprotumumab.

Fig 2.

Right (A) and left (B) lower portions of the extremity after 6 and 5 teprotumumab infusions, respectively.

Discussion

This patient with treatment-resistant PTM had significant softening and shrinking of plaques on her lower extremities after treatment with teprotumumab, an IGF-1R inhibitor. The thyrotropin receptor is uniquely targeted in Graves' disease by thyroid-stimulating autoantibodies; however, these autoantibodies are undetectable in some patients with ophthalmopathy, suggesting that other autoantigens may be involved.5 Immunoglobulins that activate IGF-1R signaling have been detected in patients with Graves' disease, and IGF-1R inhibitory antibodies have been shown to attenuate the actions of thyrotropin and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins isolated from patients with Graves' disease.5 Given the evidence that the IGF-1R and TSH receptor form a physical and functional complex in orbital fibroblasts6 and that IGF-1R is overexpressed by orbital fibroblasts7 in Graves' disease, the clinical benefits of teprotumumab on ophthalmopathy may result from attenuation of pathogenic signaling mediated through both IGF-1R and the thyrotropin receptor.

The mechanism of IGF-1R suppression in the alleviation of both ophthalmopathy and PTM remains unknown. It is possible that teprotumumab attenuates the actions of both IGF-1 and TSH in fibrocytes, specifically by blocking the induction of proinflammatory cytokines by TSH.8 It is also possible that either IGF-1R expression on fibroblasts or the affinity to IGF-1 is upregulated, resulting in oversecretion of hyaluronic acid in response to IGF-1.3 These hypothesized rationales should be investigated in future studies. Potential confounding variables in this patient's improvement on teprotumumab include concurrent treatment with pentoxifylline and methimazole. The patient's smoking reduction during treatment is another potential confounder as smoking can exacerbate PTM.2 I&D for the treatment of PTM is rarely described in the literature but was described by Grais in 1949, who treated a patient's left leg with injected hyaluronidase and the right leg with I&D.9 Hydrolysis of hyaluronic acid in the injected leg and mechanical drainage in the I&D leg caused the plaques to recede in size bilaterally. Although I&D was performed during our patient's treatment, a reduction in the size of the plaques was observed before. These treatments were adjunctive to remove small amounts of remaining mucin and did not cause a significant reduction in the size of the plaques seen during therapy. Finally, the bullous lesions developed due to softening of the patient's PTM and may be an expected response during teprotumumab therapy. At 5 months posttreatment, recurrence of the patient's PTM was noted with hardening and increased size of plaques on her lower extremities. This may highlight a temporary effect of teprotumumab on the treatment of PTM. Further studies need to be performed on the long-term efficacy of teprotumumab in the treatment of PTM and the safety of repeat treatments.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Engin B., Gümüşel M., Ozdemir M., Cakir M. Successful combined pentoxifylline and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide treatment of severe pretibial myxedema. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13(2):16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolognia J.L., Schaffer J.V., Cerroni L., Callen J.P., Rongioletti F. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018. Mucinosis. essay. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shinohara M., Hamasaki Y., Katayama I. Refractory pretibial myxoedema with response to intralesional insulin-like growth factor 1 antagonist (octreotide): downregulation of hyaluronic acid production by the lesional fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(5):1083–1086. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisti E., Coco B., Menconi F. Intravenous glucocorticoid therapy for Graves' ophthalmopathy and acute liver damage: an epidemiological study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(3):269–276. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith T.J., Kahaly G.J., Ezra D.G. Teprotubmumab for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1748–1761. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varma A., Rheeman C., Levitt J. Resolution of pretibial myxedema with teprotumumab in a patient with Graves disease. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(12):1281–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsui S., Naik V., Hoa N. Evidence for an association between thyroid-stimulating hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors: a tale of two antigens implicated in Graves' disease. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):4397–4405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H., Mester T., Raychaudhuri N. Teprotumumab, an IGF-1R blocking monoclonal antibody inhibits TSH and IGF-1 action in fibrocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(9):E1635–E1640. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grais M.L. Local injections of a preparation of hyaluronidase in the treatment of localized (pretibial) myxedema. J Invest Dermatol. 1949;12(6):345–348. doi: 10.1038/jid.1949.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]