Significance

In the United States, Black households and White households have very different conversations about race. After the death of George Floyd, Black parents were even more likely to have such conversations with their children and to prepare their children to experience racial bias than they were before Floyd’s death. White parents were less likely to talk about being White and more likely to socialize their children toward colorblindness. In addition, White parents remained relatively unconcerned that their children may experience or perpetrate racial bias.

Keywords: racial inequality, parents, children, racial socialization, colorblindness

Abstract

Research has shown that Black parents are more likely than White parents to have conversations about race with their children, but few studies have directly compared the frequency and content of these conversations and how they change in response to national events. Here we examine such conversations in the United States before and after the killing of George Floyd. Black parents had conversations more often than White parents, and they had more frequent conversations post-Floyd. White parents remained mostly unchanged and, if anything, were less likely to talk about being White and more likely to send colorblind messages. Black parents were also more worried than White parents—both that their children would experience racial bias and that their children would perpetrate racial bias, a finding that held both pre- and post-Floyd. Thus, even in the midst of a national moment on race, White parents remained relatively silent and unconcerned about the topic.

Mom, I love you. I love you. Tell my kids I love them. I’m dead. I can’t breathe.

—George Floyd

As George Floyd lay dying on the street in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25, 2020, the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin on his neck, he called out for his mother and children.

For Black Americans, such violence is inherently familial and has been since the beginning of the United States when Africans were forced into slavery. Today, systemic racism remains a core aspect of the Black American experience (1), reinforcing racial inequality across major sectors of life, from education and employment to housing and health (2–5). Consequentially, Black parents frequently have “the talk” with their children, seeking to prepare them to experience and combat the biases that could one day kill them (6–8).

White Americans are not only less likely to be harmed by systemic racism than Black Americans, they are often advantaged by it (9, 10). In contrast to Black parents, White parents are less likely to talk with their children about race (11, 12), and when they do, despite decades of research documenting the pitfalls of colorblindness (13–15), they often tell their children that race is inconsequential, a privilege Black parents do not feel they can afford (12, 16).

Sampling nearly 1,000 parents—half recruited shortly before Floyd’s death and half recruited shortly after—we provide here a rare window into how Black and White parents in the United States talk about race and racism (see Table 1 for sample demographics). A handful of studies suggest that in the wake of a racially charged killing (e.g., Trayvon Martin), Black parents will talk with their children about that specific killing (17, 18). Other studies suggest that White parents mostly do not (19, 20). Our research goes further by systematically comparing the socialization practices of Black and White parents both before and after George Floyd’s death, a death that was followed by one of the largest racial justice movements in United States history.

Table 1.

Parent and child demographics

| Sample demographics M (SD) | ||||||

| Parent race | Time | n | Parent age (y) | Child age (y) | Parent gender (% male) | Child gender (% male) |

| Black | Pre-Floyd | 260 | 37.1 (10.8) | 10.2 (4.9) | 40.8 (4.9) | 52.7 (5.0) |

| Post-Floyd | 190 | 36.7 (9.6) | 10.3 (5.0) | 37.9 (4.9) | 55.3 (5.0) | |

| White | Pre-Floyd | 279 | 38.3 (7.4) | 11.2 (5.0) | 43.0 (5.0) | 58.4 (4.9) |

| Post-Floyd | 234 | 39.6 (8.9) | 10.9 (4.7) | 39.3 (4.9) | 55.6 (5.0) | |

Demographics of the sample, broken down by parent race (Black or White) and time period (pre-Floyd or post-Floyd). Values are means (unless otherwise noted), with SDs in parentheses.

One possibility is that the unprecedented response to Floyd’s death (e.g., international protests, media campaigns, calls for criminal justice reform) resulted in increased conversations about race and racism among Black and White families (21). Alternatively, these conversations may have increased in Black families but not in White families. For Black families, witnessing the killing of an ingroup member is a traumatic experience that is central to ingroup identity and is therefore discussed and processed with ingroup members, especially loved ones; whereas for White families, witnessing the killing of an outgroup member may not elicit the need to have such discussions (22, 23). Our data allow us to test these possibilities, thereby giving us insight into the potential impact of a national “moment.”

We also move beyond prior research by not only focusing on parents’ broad conversations about race, but their conversations about racial inequality and racial identity (i.e., being Black or White) as well, which are interconnected and tap into meaningful aspects of the United States experience (10). Thus, whereas previous research has focused either on a specific killing after the fact or on generic conversations about race decontextualized from the timing of those conversations, here we provide insight into Black and White parents’ conversations about race, inequality, and identity both before and after a racially charged killing. Doing so provides a rare and more comprehensive glimpse into the role of such killings in parents’ racial socialization practices.

Results

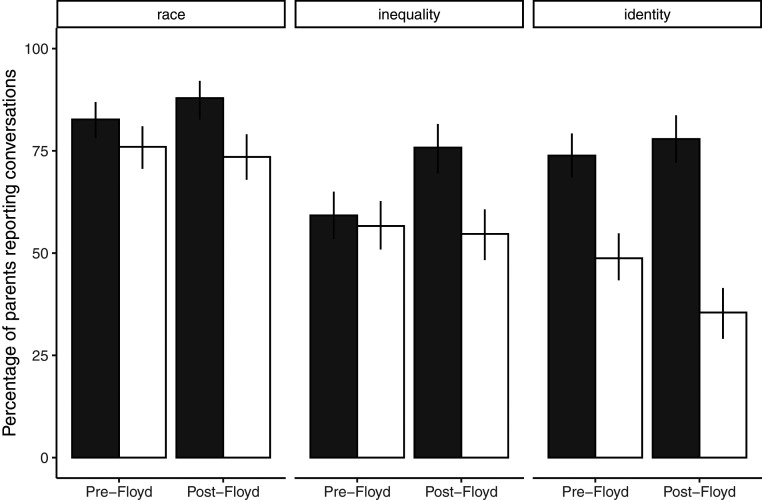

We first examined the proportion of parents engaged in conversations about race, racial inequality, and racial identity (Fig. 1). More Black parents, compared to White parents, reported conversations about all three topics (χ2s = 23.16 to 129.88, Ps < 0.001). But conversations about inequality and identity varied with time. Black parents’ conversations about inequality increased from pre-Floyd to post-Floyd (χ2 = 12.73, P < 0.001), whereas White parents were unchanged (χ2 = 0.12, P = 0.73). Indeed, differences between Black and White parents were nonsignificant pre-Floyd (χ2 = 0.27, P = 0.60), but significant post-Floyd (χ2 = 19.37, P < 0.001). Black parents’ conversations about being Black remained high and unchanged from pre-Floyd to post-Floyd (χ2 = 0.77, P = 0.38), whereas White parents’ conversations about being White decreased from pre-Floyd to post-Floyd (χ2 = 8.63, P = 0.003). Black and White parents differed significantly pre-Floyd (χ2 = 34.55, P < 0.001) and post-Floyd (χ2 = 74.40, P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Rates of conversation. Percentages of Black (gray bars) and White (white bars) parents reporting conversations across topics pre-Floyd and post-Floyd. Error bars represent bootstrapped SEs.

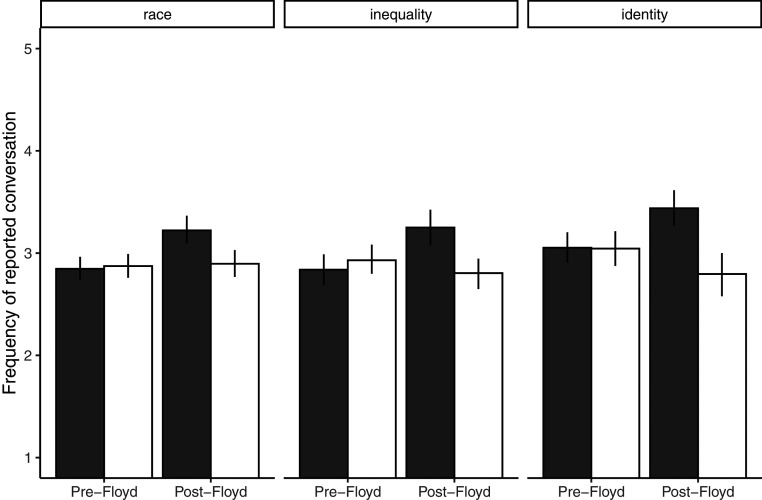

We next focused on parents who talked about race (n = 766), inequality (n = 584), and identity (n = 559), and examined the frequency of those conversations (Fig. 2). Pre-Floyd, Black and White parents reported similar frequencies of conversation across topics (ts = −0.07 to 0.87, Ps ≥ 0.38). Post-Floyd, Black parents increased their frequency (ts = 3.24 to 3.96, Ps ≤ 0.001), whereas White parents remained unchanged (ts = 0.26 to −1.80, Ps ≥ 0.07). Indeed, post-Floyd, Black parents reported more frequent conversations than White parents (ts = 3.34 to 4.58, Ps < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Frequencies of conversations. Reported frequencies of conversations among Black (gray bars) and White (white bars) parents who report conversations across topics pre-Floyd and post-Floyd. Error bars represent bootstrapped SEs.

We next focused on the content of parents’ conversations. Because there were few differences by topic, we present the findings here collapsed across topic (see SI Appendix for analyses by topic). Black parents were more likely than White parents to prepare their children to experience bias, both pre-Floyd (43% of conversations vs. 1% of conversations, χ2 = 257.69, P < 0.001) and post-Floyd (62% vs. 1%, χ2 = 347.98, P < 0.001), and were more likely to do so post-Floyd (χ2 = 37.56, P < 0.001), whereas White parents remained unchanged (χ2 = 0.07, P = 0.80). In contrast, White parents were more likely than Black parents to give their children colorblind messages, both pre-Floyd (14% of conversations vs. 6% of conversations, χ2 = 18.31, P < 0.001) and post-Floyd (21% vs. 6%, χ2 = 37.74, P < 0.001), and were more likely to do so post-Floyd (χ2 = 7.24, P = 0.007), whereas Black parents remained unchanged (χ2 = 0.03, P = 0.87). Here are two illustrative quotes, one from a Black parent preparing their child to experience bias, and another from a White parent socializing their child to be colorblind:

I told him about my godfather. He was driving…and police shot the car up thinking it was stolen. They pulled [him] out the car and beat his dead body. His story was never on the news. – Black parent to their 6-y-old child.

Everyone is treated equal. The color of your skin doesn’t matter. – White parent to their 6-y-old child.

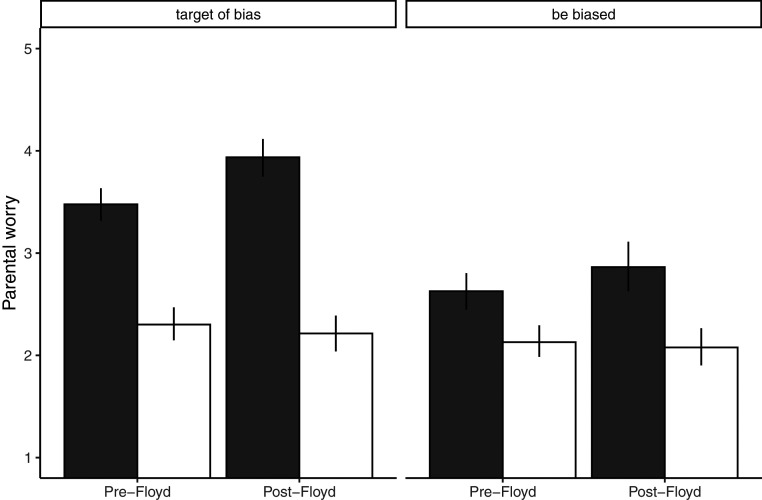

Finally, we focused on parents’ worries about whether their children might be targets of racial bias or biased themselves. Black parents were more worried than White parents that their children would be targets of bias, both pre-Floyd (t = 10.29, P < 0.001) and post-Floyd (t = 13.36, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3), and their high worry increased post-Floyd (t = 3.73, P < 0.001), while White parents’ low worry remained unchanged (t = −0.73, P = 0.47). Interestingly, Black parents were also more worried than White parents that their children would be racially biased, both pre-Floyd (t = 4.06, P < 0.001) and post-Floyd (t = 5.18, P < 0.001), and this worry didn’t change post-Floyd for either group (Black: t = 1.53, P = 0.13; White: t = −0.44, P = 0.66). We theorized that Black parents’ higher worry compared to White parents might explain their higher overall likelihood of having conversations with their children. Indeed, for both Black and White parents, increased worry on both measures predicted increased likelihood and frequency of conversations (collapsed across topic) (SI Appendix, Table S4). Critically, though, White parents’ worry stayed low and flat from pre- to post-Floyd, paralleling their relatively low rates of conversation and lack of change post-Floyd.

Fig. 3.

Parental worry. Reported worry that their child will be a target of bias (Left) or will be biased (Right) among Black (gray bars) and White (white bars) parents pre-Floyd and post-Floyd. Error bars represent bootstrapped SEs.

Discussion

Overall, these data reveal how Black and White parent–child conversations about race and racism changed (or remained unchanged) in the wake of George Floyd’s death. After Floyd’s death, Black parents had more frequent conversations about race and racism, were more likely to prepare their children to experience bias, and indeed, were more concerned that their children would experience bias. White parents, in contrast, remained mostly unchanged, and if anything became more likely to socialize their children toward colorblindness. Colorblindness may be a well-intentioned socialization strategy, but can backfire by reducing children’s ability to identify and combat racial inequality (13). Thus, even in the wake of national attention toward race relations, White parents maintained a relatively ineffective approach to discussing race and racism with their children, an approach that can allow racism to remain unaddressed and underrecognized (10). Thus, the results reported here call into question the broader role of national moments to drive widespread social change on their own.

Because we relied on parental self-reports (which are not necessarily predictive of children’s attitudes) (24), the present data may overstate the actual rates of parental racial socialization. Indeed, although over 70% of White parents reported conversations about race, only 50% or fewer reported conversations about inequality or identity, which are central to the United States racial experience (10). Additionally, after asking White parents about the content of those conversations, we found that over 50% of the conversations fell outside of our coding scheme, often because they were uninformative (e.g., “nothing really”) or vague (e.g., “I told him everything he needed to know”). Thus, although a high proportion of White parents reported conversations about race, a much smaller proportion engaged in conversations that they could recount or that were focused and effective (also see refs. 16 and 25).

Relatedly, Black parents were more worried than White parents that their children would experience bias, and they were even more worried post-Floyd, which aligns with research showing that in the wake of Floyd’s killing, Black Americans experienced an unprecedented decline in emotional and mental health (26; see also ref. 22). Meanwhile, White parents not only expressed little worry that their children might experience bias, but that they could be biased and this predicted lower rates and frequencies of conversations about race, whether those conversations occurred before or after Floyd’s death. This link between worry and conversations suggests that one way to encourage White parents to have these conversations may be to increase their awareness that their children may exhibit bias and that bias can lead to harm. Until White parents begin to talk with their children about racial biases, Black parents may have no choice but to continue to prepare their children to experience them.

Lack of worry may not be the only barrier to talking about race. Even for White parents motivated to have such conversations, little research offers guidance on how to do so effectively. Theoretical work (27) and work with adults (15) suggest possible avenues toward effective conversations, but little empirical work exists to pinpoint specific strategies that parents can use to reduce children’s racial biases (28). How might the scientific literature guide parents toward effective ways to have conversations with children about race? What does an effective conversation even look like? Given the reality and brutality of racism and racial inequality, the time to answer these questions, and to have these conversations, is now.

Materials and Methods

In 2020, we recruited two mutually exclusive samples of Black and White United States parents, one in April (∼6 wk before Floyd’s death) and one in June (∼3 wk after Floyd’s death). Each sample consisted of both monoracial Black parents of monoracial Black children (n1 = 260; n2 = 190) and monoracial White parents of monoracial White children (n1 = 279; n2 = 234; for full demographics see SI Appendix, Table S1). We recruited parents of children aged 0 to 18 y to better understand socialization practices across development (due to space limitations we do not explore effects of child age or other demographic variables in the main text, but our full models are available in SI Appendix). All procedures were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board and all participants completed informed consent before beginning the study.

Parents at both time points completed identical surveys that assessed their racial socialization practices. The survey was split into three sections (i.e., conversations about race, racial inequality, racial identity). Within each, there were three major questions. First, parents were asked whether or not they have conversations with their child about the section’s topic. Second, parents who answered “yes” were then asked how frequently they have those conversations (1 = never, 5 = daily). Third, parents were asked to share a recent conversation with their child. These open-ended responses, which allowed parents to use their own vocabularies and provide unconstrained responses, were coded by trained research assistants. Thus, we examined whether parents had these conversations, how frequently they did, and what those conversations were about. Finally, parents were asked how worried they were that their child might be: 1) a target of racial bias, and 2) racially biased (1 = not at all worried, 5 = extremely worried). We used these questions to probe possible motivations for parents’ conversations, as parents worried about the impact of race on their child may be more likely to discuss it. Here, we highlight our most important findings, but all data are publicly accessible via the SI Appendix (29).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Noah Bartelt, Claire Lund, James Márquez, Jeong Shin, and Griffin Somaratne for assistance with qualitative coding; and Sakaria Auelua-Toomey, Carmelle Bareket-Shavit, Elizabeth Mortenson, and Kheshawn Wynn for their feedback on previous versions of this manuscript. This research was funded by a Stanford University grant (to S.O.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2106366118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All data, code, and materials are publicly available online at Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/esbpk.

References

- 1.Roberts S. O., Bareket-Shavit C., Wang M., The souls of Black folks (and the weight of Black ancestry) in U.S. Black Americans’ racial categorization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eberhardt J. L., Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice that Shapes What We See, Think, and Do (Penguin Books, New York, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krieger N., Discrimination and health inequities. Int. J. Health Serv. 44, 643–710 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okonofua J. A., Walton G. M., Eberhardt J. L., A vicious cycle: A social–psychological account of extreme racial disparities in school discipline. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11, 381–398 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pager D., Shepherd H., The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 34, 181–209 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes D., Chen L., When and what parents tell children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Appl. Dev. Sci. 1, 200–214 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes D., et al., Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Dev. Psychol. 42, 747–770 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas A. J., Speight S. L., Racial identity and racial socialization attitudes of African American parents. J. Black Psychol. 25, 152–170 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salter P. S., Adams G., Perez M. J., Racism in the structure of everyday worlds: A cultural-psychological perspective. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 27, 150–155 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts S. O., Rizzo M. T., The psychology of American racism. Am. Psychol. 76, 475–487 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loyd A. B., Gaither S. E., Racial/ethnic socialization for White youth: What we know and future directions. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 59, 54–64 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pahlke E., Bigler R. S., Suizzo M. A., Relations between colorblind socialization and children’s racial bias: Evidence from European American mothers and their preschool children. Child Dev. 83, 1164–1179 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apfelbaum E. P., Pauker K., Sommers S. R., Ambady N., In blind pursuit of racial equality? Psychol. Sci. 21, 1587–1592 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonilla-Silva E., Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plaut V. C., Thomas K. M., Hurd K., Romano C. A., Do color blindness and multiculturalism remedy or foster discrimination and racism? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 27, 200–206 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vittrup B., Color blind or color conscious? White American mothers’ approaches to racial socialization. J. Fam. Issues 39, 668–692 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas A. J., Blackmon S. K. M., The influence of the Trayvon Martin shooting on racial socialization practices of African American parents. J. Black Psychol. 41, 75–89 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Threlfall J. M., Parenting in the shadow of Ferguson: Racial socialization practices in context. Youth Soc. 50, 255–273 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abaied J. L., Perry S. P., Socialization of racial ideology by White parents. Cult. Divers. Ethn Min. 27, 431–440 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Underhill M. R., Parenting during Ferguson: Making sense of white parents’ silence. Ethn. Racial Stud. 41, 1934–1951 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayers J. W., et al., Quantifying public interest in police reforms by mining internet search data following George Floyd’s death. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e22574 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bor J., Venkataramani A. S., Williams D. R., Tsai A. C., Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet 392, 302–310 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown R., Kulik J., Flashbulb memories. Cognition 5, 73–99 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes D., et al., “How to catch a moonbeam: A mixed-methods approach to understanding ethnic socialization in ethnically diverse families” in Handbook of Race, Racism, and Child Development, Quintana S., Mckown C., Eds. (Wiley, 2008), pp. 226–277. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesane-Brown C. L., Brown T. N., Tanner-Smith E. E., Bruce M. A., Negotiating boundaries and bonds: Frequency of young children’s socialization to their ethnic/racial heritage. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 41, 457–464 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eichstaedt J. C., et al., The emotional and mental health impact of the murder of George Floyd on the US population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2109139118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bigler R. S., Liben L. S., Developmental intergroup theory: Explaining and reducing children’s social stereotyping and prejudice. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 16, 162–166 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott K. E., Shutts K., Devine P. G., Parents’ role in addressing children’s racial bias: The case of speculation without evidence. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 1178–1186 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan J. N., Eberhardt J. L., Roberts S. O., Parent race talk & George Floyd. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/esbpk. Deposited 11 March 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data, code, and materials are publicly available online at Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/esbpk.