Graphical abstract

Keywords: Epidemiology, HDV, hepatitis D, Liver transplantation

Abstract

Introduction

Hepatitis D Virus (HDV) infection is vanishing in Italy. It is therefore believed that hepatitis D is no longer a medical problem in the domestic population of the country but remains of concern only in migrants from HDV-endemic areas.

Objectives

To report the clinical features and the medical impact of the residual domestic HDV infections in Italy.

Methods

From 2010 to 2019, one hundred ninety-three first-time patients with chronic HDV liver disease attended gastroenterology units in Torino and San Giovanni Rotondo (Apulia); 121 were native Italians and 72 were immigrants born abroad. For this study, we considered the 121 native Italians in order to determine their clinical features and the impact of HDV disease in liver transplant programs.

Results

At the last observation the median age of the 121 native Italians was 58 years. At the end of the follow-up, the median liver stiffness was 12.0 kPa (95% CI 11.2–17.4), 86 patients (71.1%) had a diagnosis of cirrhosis; 80 patients (66.1%) remained HDV viremic. The ratio of HDV to total HBsAg transplants varied from 38.5% (139/361) in 2000–2009 to 50.2% (130/259) in 2010–2019, indicating a disproportionate role of hepatitis D in liver transplants compared to the minor prevalence of HDV infections in the current scenario of HBsAg-positive liver disorders in Italy.

Conclusion

Though HDV is vanishing in Italy, a legacy of ageing native-Italian patients with advanced HDV liver disease still represents an important medical issue and maintains an impact on liver transplantation.

Introduction

Since the discovery of the Hepatitis D Virus (HDV) in the 1970 s, the prevalence of this infection and the medical impact of hepatitis D have much diminished in the Western World [1]. Critical to the control of the infection was the implementation of vaccination against the Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), which has led to the depletion of carriers of the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) necessary for the HDV to disseminate.

Italy has been central to the monitoring of the epidemiology of HDV infection throughout the last four decades [2], [3], [4]. The country was the first among industrialized countries to introduce in 1991 universal HBV vaccination for neonates and 12-years-old adolescents [5]; by 2020, almost all 40 years old Italians are protected from the HBV and by default from hepatitis D.

The prevalence of the antibody to the HDV (anti-HD) in HBsAg carriers with liver disease diminished in Italy from 24.6% in 1983 to 8.15% at the end of the last century [6], [7]. It has then remained stable due to the input of new infections brought into the country by HDV-infected immigrants; among 786 HBsAg carriers collected in 2019, the overall prevalence of anti-HD was 9.9% and it was 6.4% in Italian-natives and 26.4% in immigrants [8].

We report in this study the clinical features and current medical impact of the residual population of native HDV-infected Italians.

Patients and methods

Study population

A total of 193 patients with chronic HDV infection were newly referred from 2010 to 2019 to the Gastroenterology Units of the University of Torino and of the Ospedale Casa Sollievo Sofferenza - IRCCS of San Giovanni Rotondo (SGR), in Northern and Southern Italy; 121 of the patients were born in Italy (native-Italians) and 72 were born abroad and immigrated to Italy. For the purpose of this study we considered only the 121 native-Italian patients.

All the 121 patients were HBsAg and anti-HD seropositive, and had a chronic liver disease diagnosed by clinical and biochemical evaluation and/or by liver elastography (FibroScan®, Echosens™, Paris, France). Their medical histories were reviewed and the medical/virological features and clinical course from presentation to the last follow-up time were determined and compared throughout a median follow-up of 8 year (range 1–9) during which they were submitted to several visits with collection of serum samples at each visit.

In addition, we analyzed data from 269 HDV liver transplants performed from 2000 to 2019 at the Liver Transplant Unit of Torino which is a national referral center for HDV transplantation; the demographic features, the ratio of HDV to HBV transplants and the reasons for transplantation were retrieved from the Torino Liver Transplant Registry.

Ethics statement

All the patients signed an informed consent to allow access to medical data, collected for research projects and which were approved by the ethic committees in the participating centers (Comitato Etico Interaziendale A.O.U. Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino - A.O. Ordine Mauriziano - A.S.L. Città di Torino, approval no. CEI-690 and Comitato Etico Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, approval no. 50/CE). All the procedures described in the present work were carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Serology and virology

The ARCHITECT-QT assay (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA) was used for the determination of human serum HBsAg [9]. HBV DNA was detected and quantified in plasma with the COBAS/AmpliPrepCOBAS TaqMan HBV test, version 2.0 (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ, USA) [10]. Total, predominantly IgG anti-HD were assessed by ETI-AB-DELTAK-2 enzyme immunoassay and IgM anti-HD by ETI-DELTA-IGMK-2 (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy). HDV RNA was detected by Real Time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) as previously described [11]. The assay was calibrated in International Units against the 1st WHO International Standard for HDV RNA [12]; it showed a linearity of quantification ranging from 2 × 102 to 2 × 109 IU/ml and a sensitivity of 293 IU/ml. The HDV genotype was determined by direct sequencing (BMR-GENOMICS, Padova, Italy) and multiple alignements using CLUSTAL-X software with the reference sequences of the eight HDV genotypes retrieved from GenBank.

Statistical analysis

Data distribution was checked by D'Agostino-Pearson normality test. Pairwise comparison of continuous variables was performed by Wilcoxon test while categorical data were compared by McNemar test or chi-squared test where appropriate. Fisher’s exact test or Mann-Whitney test were used to compare data from independent groups. For all analyses, a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc software version 18.9 (MedCalc bvba, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

HDV patients recruited from 2010 to 2019

Demographic features and risk factors

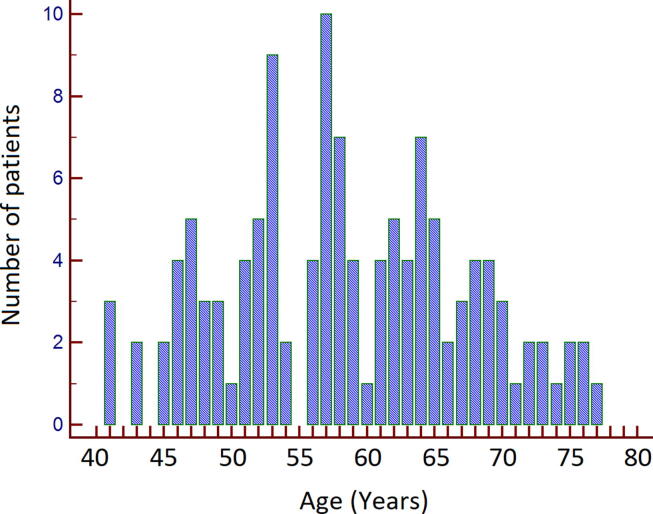

The median age at presentation and at the end of the follow-up was 50 (32–71) and 58 (41–77) years respectively; the age distribution of the patients at the end of the follow-up is shown in Fig. 1. The male to female ratio was 83/38. The median body mass index was 25.0 (18.7–38.6) Kg/m2. Thirtheen patients were obese (BMI ≥ 30 Kg/m2); 8 patients (6.6%) admitted abuse of alcohol. Only four patient had type 2 diabetes requiring therapy. Risk factors for HDV infection could be identified in 57 patients (47.1%); household and intrafamily exposure to the HDV was predominant, 15 patients (26.3%) reported intravenous drug abuse or mercenary sex.

Fig. 1.

Age distribution of the 121 native-Italians patients at the last follow-up.

Virologic and biochemical features

At recruitment, 112 (92.6%) patients were HDV-RNA seropositive; 9 patients were HDV RNA seronegative, but previous laboratory records documented that they had been previously HDV RNA positive. The genotype of HDV, determined in 25 patients, was genotype 1 in all. All the patients remained positive for anti-HD throughout the follow-up. None was or became positive for antibodies to the human immunodeficiency virus. Eight patients were positive for antibodies against the Hepatitis C Virus; none was positive for serum HCV RNA, five had previously eradicated the virus with specific antiviral treatments. The virologic, biochemical and clinical features at first observation and last observation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 121 native Italian patients at the first observation and at the last follow-up observation.

| First observation | Last follow-up | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serologic and virologic parameters | |||

| Anti-HD IgM positive, n (%) | 74 (61.2%) | 46 (38.0%) | <0.001b |

| HBsAg positive, n (%) | 121 (100%) | 112 (92.6%) | 0.003b |

| HDV RNA positive, n (%) | 112 (92.6%) | 80 (66.1%) | <0.001b |

| HDV RNA positive (<2000 IU/mL), n (%) | 16 (14.3%) | 18 (22.5%) | |

| HDV RNA positive (2000–100000 IU/mL), n (%) | 24 (21.4%) | 26 (32.5%) | <0.001c |

| HDV RNA positive (>100000 IU/mL), n (%) | 72 (64.3%) | 36 (45.0%) | |

| HBV DNA positive, n (%) | 107 (88.4%) | 67 (55.4%) | <0.001b |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| ALT (U/L), median (range) | 76 (14–410) | 49 (13–565) | 0.002d |

| AST (U/L), median (range) | 64 (20–186) | 48 (12–248) | 0.026d |

| Platelet count (x 109/L), median (range) | 149 (46–298) | 121 (23–331) | 0.026d |

| INR, median (range) | 1.10 (0.91–1.51) | 1.15 (0.90–1.94) | 0.380d |

| Albumin (g/dL), median (range) | 4.3 (3.5–5.1) | 4.0 (2.2–4.9) | 0.011d |

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Liver stiffness (kPa), median (95% CI)a | 11.0 (7.0–12.5) | 12.0 (11.2–17.4) | 0.081d |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 65 (53.7%) | 86 (71.1%) | <0.001b |

| Ascites, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (25.6%) | <0.001b |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; anti-HD, antibodies to the HDV; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; INR, international normalized ratio; N, number

performed in 83 patients (68.6%).

calculated by McNemar test.

calculated by chi-squared test.

calculated by Wilcoxon test.

From the first observation to the end of the follow-up, 28 out of 74 patients (37.8%) lost IgM antibodies to HDV and 9 (7.4%) became HBsAg seronegative. Among viremic patients, the median serum HDV RNA decreased from 268250 IU/mL (95% CI 114508–1137672) to 81900 IU/mL (95% CI 33383–149683) (P < 0.001); 32 of 112 (28.6%) became HDV RNA negative. The percentage of the patients with HDV RNA positive below 2000 IU/mL and between 2000 and 100000 IU/mL increased by 8.2% and 11.1%, respectively, while the percentage of patients with HDV RNA above 100000 IU/mL decreased by 19.5%. The number of HBV DNA positive patients diminished from 107 (88.4%) to 67 (55.4%), with a median value HBV DNA of 40 IU/mL (95% CI 22–94) at the last observation.

Clinical features

A past diagnosis of severe active hepatitis or cirrhosis was recorded in 93 patients (76.9%) The other 28 patients (23.1%) had been symptom-free and they were either unaware until recently of a viral liver disease or reported a past diagnosis of only minor and apparently irrelevant liver alterations; there were 7 patients belonging to a subgroup of 13 who had a histological diagnosis of mild chronic hepatitis D (CHD) (Ishak score: staging ≤ 2, grading ≤ 3) made in Torino in the 1980–1990 s [3]; as their liver tests remained normal or borderline for up to 8 years of follow-up, they had been dismissed from further surveillance [3].

At presentation to this study, the median liver stiffness of the patients was 11.0 kPa (95% CI 7.0–12.5); a cirrhosis had been diagnosed by histology in 13 of 36 (29.8%) patients who underwent a liver biopsy, and by liver stiffness (≥12.5 kPa) or clinical features (i.e. nodular hepatomegaly, splenomegaly) in 52 other patients.

Throughout the follow-up, the median value of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), platelet count and albumin diminished significantly; the INR did not change. Thirty-two patients (26.4%) underwent nucleos(t)ide analogues treatment to prevent possible recrudescence of hepatitis B. Nineteen patients (15.7%) were treated with Peg-IFN; nine attained a sustained response, five lost the HBsAg. In four patients, the HBsAg cleared spontaneously from serum. Other 23 patients became spontaneously HDV RNA negative during the follow-up; 11 had been previously given IFN-based treatment without achieving viral eradication.

At the last follow-up observation, the median liver stiffness value was 12.0 kPa (95% CI 11.2–17.4). Thirty-one (25.6%) patients developed ascites and 20 (16.5%) a hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Eleven died; 27 (22.3%) underwent liver transplantation, 13 (48.1%) for HCC and 14 (51.9%) for liver failure.

HDV liver transplants from 2000 to 2019

One thousand three hundreds ninety-one and 1255 liver transplants were performed in Torino in the decade 2000–2009 and 2010–2019 respectively, of which 361 (25.9%) and 259 (19.0%) in HBsAg carriers; 139 (38.7%) and 130 (50.2%) of the HBsAg-positive patients were coinfected with the HDV. The demographic and clinical data are reported in Table 2. The 269 HDV-positive recipients were significantly younger than the 351 HBV monoinfected recipients (51.1 [50.0–52.7] years vs. 56.4 [55.7–57.1]; P < 0.001). The ratio of HDV to total HBsAg transplants was 38.5% (139/361) in 2000–2009, and 50.2% (130/259) in 2010–2019 (P = 0.004). The prevalent indication for transplantation was liver failure in the HDV coinfected patients (191/269; 71.0%) and HCC in the HBV monoinfected (212/351; 60.3%) (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

HDV and HBV transplants performed in Torino from 2000 to 2019.

| 2000–2009 |

2010–2019 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | HDV positive | HBV monoinfected | Overall | HDV positive | HBV monoinfected | |

| LT, N (%) | 361 | 139 (38.5%) | 222 (61.5%) | 259 | 130 (50.2%) | 129 (49.8%) |

| Age (years), median (95% CI) | 52.8 (51.9–54.1) | 48.6 (46.6–50.7) | 55.3 (54.2–56.1) | 56.7 (55.6–57.2) | 54.3 (52.3–55.7) | 58.0 (57.1–59.8) |

| Gender, M/F | 303/58 | 102/37 | 201/21 | 211/48 | 95/35 | 116/13 |

| Indication for transplantation: | ||||||

| HCC | 29/139 (20.9%) | 121/222 (54.5%) | 49/130 (37.7%) | 91/129 (70.5%) | ||

| Liver failure | 110/139 (79.1%) | 101/222 (45.5%) | 81/130 (62.3%) | 38/129 (29.5%) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; N, number; M/F, male to female ratio; LT, liver transplantation.

Discussion

This is the last of four surveys [2], [3], [4] which reported the natural history of HDV infection as it unfolded in Italy from the discovery of the virus in the late 1970 s to the present time. From the first report in 1983 [2] to the second in 1999 [3] the perception of CHD changed from a severe disease frequently predisposing to liver failure to a picture including also minor liver disorder, and in the third report in 2010 [4] the mean age of the patients and the prevalence of cirrhosis had significantly increased.

Now and then, the patients were collected in the same reference gastroenterology units in Torino and Apulia but in the meanwhile the diagnostic methodology has changed; in the previous series the diagnosis was based on a liver biopsy but in the present series it was based primarily on positive HDV serology and abnormal liver elastography.

In keeping with the epidemiologic demise of the HDV among native Italians, we have not observed new and fresh forms of CHD but only advanced liver diseases. The infection is outliving in ageing patients, whose disease is diminishing in viral and inflammatory activity; at the end of the follow-up their median age was 58 years, i.e. 8 years older than the patients recruited in the 1991–2005 survey [4], and the median ALT level, the rate of IgM anti-HD-positivity and the percentage of viremic patients had consistently diminished. Though one fourth of the patients cleared serum HDV-RNA and 7.4% cleared the HBsAg, 71.4% of the 80 patients who remained viremic maintained a consistent titer of serum HDV RNA, with a median of 81900 IU/mL. The changes in HD viremia were mostly spontaneous; only 9 of the 19 patients treated with Peg-IFN in this study lost the HDV RNA and 5 of them lost also the HBsAg.

Many patients had already accumulated important liver scarring at recruitment into the present survey and the liver fibrosis has further advanced during the follow-up to a median liver stiffness of 12.0 kPa; in comparison with the patients recruited in the 1991–2005 survey [4], the proportion with overt cirrhosis had increased from 56.4% to 71.1% and the percentage with HD viremia had diminished from 71.8% to 66.1%.

The disease was complicated by ascites and/or by an HCC in 44 (36.4%) patients while the clinical course was apparently uneventful in 63.6%; however, during the follow-up the median serum albumin concentration and blood platelets count diminished significantly also in the latter, indicating that portal hypertension had developed in many.

The long-term survival of cirrhotic patients with the HDV would seem surprising, as this virus causes the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis [13]. This was previously explained by a peculiar biphasic course of CHD; though in many patients CHD rapidly progressed to cirrhosis within a few years with a steep decrease in survival curves, in patients who outlived the disease abated, consenting a normal existence for decades [3]. Surprisingly, however, we found that cirrhosis had developed insidiously also in 23% of the patients of this survey who did not report a previous history of significant liver damage, suggesting that advanced HDV disease may result not only from burnt-out cirrhosis but also from an originally unassuming liver injury that progressed slowly over decades; by reason of their long natural history and survival advantage minor but insidiously progressive CHDs accumulating over time are likely to contribute an important share to the current scenario of HDV cirrhotics. The issue is of clinical relevance; in common practice, testing for HDV is often neglected in minor forms of chronic HBsAg liver disease on the belief that HDV is associated only with serious liver disease [14]. However the recognition that also these forms of are prone to evolve if related to the HDV, requires that reflex testing for anti-HD is performed in all cases of HBsAg patients; this becomes more compelling with the perspective of new therapies that promise to control hepatitis D over the long-term [15].

A perception of the residual medical burden of HDV comes also from liver transplantation registries. The number of HDV transplants performed in the decade 2010–2019 in Torino and the ratio of HDV to HBV transplants did not diminish compared to the previous decade, pointing to a disproportionate number of HDV transplants versus the minor epidemiologic weight of the infection in the contemporary HBsAg scenario [16].

The same is true from the European Liver Transplant registry. Though the residual prevalence of the HDV in the continent is much lower than the HBV, in the last 15 years the percentage of HBsAg/HDV to total HBsAg transplants amounted to 27% with a 2% increase from the 25% ratio of the previous decade [17]. The paradox may be explained by the different impact of therapy in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and in CHD. While the only therapy available for CHD remains the time-honored but low-performing alfa Interferon that failed to control HDV infection in many patients [18], the efficacious antiviral treatments used in CHB in the last 20 years have prevented in over 90% of cases the progression of CHB to terminal disease [19], drastically reducing the need for liver transplantation. Consonant with this conclusion, in the last decade 62.3% of the HDV patients were transplanted for liver failure and 37.7% for hepatocellular carcinoma while only 29.5% of the HBV patients were transplanted for liver failure and 70.5% were transplanted for a hepatocellular carcinoma, the development of which was not prevented by antiviral therapy.

In conclusion, though the HDV is vanishing in indigenous Italians, chronic HDV disease still outlives in a cohort of ageing domestic cirrhotics and maintains an impact on liver transplantation programs. The residual tail of HDV infections is bound to spontaneously extinguish in a generation time, yet with a mean age of 58 years, it will remain a medical issue for years to come.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Gian Paolo Caviglia: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing - original draft. Silvia Martini: Investigation, Data curation. Alessia Ciancio: Investigation, Data curation. Grazia Anna Niro: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Antonella Olivero: Data curation, Investigation. Rossana Fontana: Data curation, Investigation. Francesco Tandoi: Investigation, Data curation. Chiara Rosso: Software, Visualization. Renato Romagnoli: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Giorgio Maria Saracco: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Antonina Smedile: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Mario Rizzetto: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Rizzetto M., Hepatitis D. In: Clinical Epidemiology of Chronic Liver Diseases. Wong E.J., Gish R.G., editors. Springer Nature; Switzerland: 2019. Virus; pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzetto M., Verme G., Recchia S., Bonino F., Farci P., Aricò S. Chronic HBsAg hepatitis with intrahepatic expression of the delta antigen. An active and progressive disease unresponsive to immunosuppressive treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98(4):437–441. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-4-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosina F., Conoscitore P., Cuppone R., Rocca G., Giuliani A., Cozzolongo R. Changing pattern of chronic hepatitis D in southern Europe. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(1):161–166. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70563-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niro G.A., Smedile A., Ippolito A.M., Ciancio A., Fontana R., Olivero A. Outcome of chronic delta hepatitis in Italy: a long-term cohort study. J Hepatol. 2010;53(5):834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanetti A.R., Tanzi E., Romanò L., Grappasonni I. Vaccination against hepatitis B: the Italian strategy. Vaccine. 1993;11(5):521–524. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90222-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smedile A., Lavarini C., Farci P., Aricò S., Marinucci G., Dentico P. Epidemiologic patterns of infection with the hepatitis B virus-associated delta agent in Italy. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117(2):223–229. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaeta G.B., Stroffolini T., Chiaramonte M., Ascione T., Stornaiuolo G., Lobello S. Chronic hepatitis D: a vanishing Disease? An Italian multicenter study. Hepatology. 2000;32(4 Pt 1):824–827. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroffolini T., Ciancio A., Furlan C., Vinci M., Fontana R., Russello M. Migratory Flow and Hepatitis Delta Infection in Italy: A New Challenge at the Beginning of the Third Millennium. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27(9):941–947. doi: 10.1111/jvh.13310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burdino E., Ruggiero T., Proietti A., Milia M.G., Olivero A., Caviglia G.P. Quantification of hepatitis B surface antigen with the novel DiaSorin LIAISON XL Murex HBsAg Quant: correlation with the ARCHITECT quantitative assays. J Clin Virol. 2014;60(4):341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tandoi F., Caviglia G.P., Pittaluga F., Abate M.L., Smedile A., Romagnoli R. Prediction of occult hepatitis B virus infection in liver transplant donors through hepatitis B virus blood markers. Dig Liver Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.07.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niro G.A., Smedile A., Fontana R., Olivero A., Ciancio A., Valvano M.R. HBsAg kinetics in chronic hepatitis D during interferon therapy. On treatment prediction response. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(6):620–628. doi: 10.1111/apt.13734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chudy M., Hanschmann K.M., Bozsayi M., Kress J., Nubling C.M. Collaborative study to establish a World Health Organization International Standard for hepatitis D virus RNA for nucleic acid amplification technology (NAT)-base assays. WHO Report. 2013 (accessed 25 Jun 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farci P., Niro G.A. Clinical features of hepatitis D. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32(3):228–236. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizzetto M., Ciancio A. Epidemiology of hepatitis D. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32(3):211–219. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang C., Syed Y.Y. Bulevirtide: First Approval. Drugs. 2020;80(15):1601–1605. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroffolini T., Sagnelli E., Sagnelli C., Russello M., De Luca M., Rosina F. Hepatitis delta infection in Italian patients: towards the end of the story? Infection. 2017;45(3):277–281. doi: 10.1007/s15010-016-0956-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adam R., Karam V., Cailliez V., O Grady J.G., Mirza D., Cherqui D. 2018 Annual Report of the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR) - 50-year Evolution of Liver Transplantation. Transpl Int. 2018;31(12):1293–1317. doi: 10.1111/tri.13358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizzetto M., Yurdaydin C. In: Hepatitis D: Virology, management and methodology. Rizzetto M., Smedile A., editors. Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore; Rome: 2019. Interferon and nucleic acid polymers in the therapy of chronic hepatitis D; pp. 303–315. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong V.W., Chan H.L. Chronic hepatitis B: a treatment update. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33(2):122–129. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1345715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]