Abstract

Background and objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced universities to move the completion of university studies online. Spain’s National Conference of Medical School Deans coordinates an objective, structured clinical competency assessment called the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), which consists of 20 face-to-face test sections for students in their sixth year of study. As a result of the pandemic, a computer-based case simulation OSCE (CCS-OSCE) has been designed. The objective of this article is to describe the creation, administration, and development of the test.

Materials and methods

This work is a descriptive study of the CCS-OSCE from its planning stages in April 2020 to its administration in June 2020.

Results

The CCS-OSCE evaluated the competences of anamnesis, exploration, clinical judgment, ethical aspects, interprofessional relations, prevention, and health promotion. No technical or communication skills were evaluated. The CCS-OSCE consisted of ten test sections, each of which had a 12-min time limit and ranged from six to 21 questions (mean: 1.1 min/question). The CCS-OSCE used the virtual campus platform of each of the 16 participating medical schools, which had a total of 2829 students in their sixth year of study. It was jointly held on two dates in June 2020.

Conclusions

The CCS-OSCE made it possible to bring together the various medical schools and carry out interdisciplinary work. The CCS-OSCE conducted may be similar to Step 3 of the United States Medical Licensing Examination.

Keywords: OSCE, Objective structured clinical examination, Online, Computer-based case simulation, Spain

Abstract

Antecedentes y objetivos

La pandemia de la COVID-19 ha obligado a completar los estudios universitarios online. La Conferencia Nacional de Decanos de Facultades de Medicina coordina una prueba de evaluación de competencias clínicas objetiva y estructurada (ECOE) de 20 estaciones presenciales a los estudiantes de sexto del grado. Como consecuencia de la pandemia se ha diseñado una ECOE sustitutoria con casos-clínicos computarizados simulados (ECOE-CCS). El objetivo del artículo es describir la elaboración, la ejecución y el desarrollo de la prueba.

Materiales y métodos

Estudio descriptivo de la ECOE-CCS conjunta desde su gestación en abril 2020 hasta su ejecución en junio 2020.

Resultados

La ECOE-CCS evaluó las competencias de anamnesis, exploración, juicio clínico, aspectos éticos, relaciones interprofesionales, prevención y promoción de la salud. No se evaluaron habilidades técnicas ni de comunicación. La ECOE-CCS consistió en 10 estaciones de 12 minutos de duración, con un número de preguntas de seis a 21 (media: 1,1 minutos/pregunta). En la ECOE-CCS se utilizó la plataforma virtual del campus de cada una de las 16 facultades de Medicina que participaron, con un total de 2.829 estudiantes de sexto curso. Se realizó de una forma conjunta en dos fechas de junio del 2020.

Conclusiones

La experiencia de la ECOE-CCS permitió llevar a cabo una integración y el trabajo interdisciplinar de las diferentes facultades de Medicina. La ECOE-CCS realizada podría asemejarse al Step 3 CCS de la United States Medical Licensing Examination.

Palabras clave: ECOE, Examen clínico objetivo y estructurado, Virtual, Casos clínicos computarizados simulados, España

Introduction

Throughout history, clinical competence has been evaluated using instruments such as an examination before a real patient. This traditional form of evaluation, however, makes it difficult to explicitly assess all components that comprise clinical competence1. In 1975, Harden began direct observation through multiple structured stations with a list of assessable aspects: the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE)2, 3, 4.

Spain’s National Conference of Medical School Deans (CNDFME, for its initials in Spanish) established shared criteria for a 20-station OSCE-type test that all sixth-year medical students must take5. This test, which is practical in nature, is aimed at evaluating the student’s professional competence in accordance with the specific competences of a degree in medicine established by Order ECI/332/20086, published in Spain’s Official State Gazette on 02/15/2008, through the resolution of clinical cases and demonstration of skills5.

Medical schools (MS) generally hold the OSCE in a clinical setting. The test explores competences through different methods and the stations include standardized patients, mannequins, short-answer questions, the conduct of additional tests according to the case, the writing of clinical reports, a structured oral examination, skills and procedures, and stations with a computer or simulators7, 8, 9.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed our lives in 2020. The state of alarm that was declared made it necessary to complete university studies online10. Therefore, the CNDFME’s national committee for the test approved holding substitute virtual tests. Within the agreements regarding the test, 16 MS decided to develop a computer-based case simulation OSCE (CCS-OSCE) to be administered via each university’s online campus platform as part of a joint project for innovation.

The aim of this article is to describe the creation, development, and administration of the CCS-OSCE.

Methods

Study type

This work is a descriptive study of the process of creating, developing, and administering the CCS-OSCE since its inception in April 2020 to its administration in June 2020.

Creation of the CCS-OSCE

On March 25, 2020, with the state of alarm already in force, the National Committee for the OSCE-CNDFME test agreed to form working groups to create a database of cases and questions for a virtual OSCE test that could be simultaneously administered in each MS (see Supplementary material).

Two weeks later, two sets of working groups were formed. Of the 40 MS who should have done the OSCE-CNDFME test in the 2019–2020 school year, 21 (52.5%) decided to join one of the groups to share a common test. Of these, 16 MS (76.2%) developed and shared the CCS-OSCE that is the subject of this work and five MS (23.8%) joined the working group which used the Fundación Practicum-Script® platform.

Starting on April 25, weekly online meetings were held with the 16 MS who participated in the CCS-OSCE with shared common cases. Other coordinators from the remaining MS joined to share experiences and discuss organizational aspects. The project began by establishing a competency map, the number of stations necessary, and the number of items per competence. The dates for administering the exam were set.

In Table 1 , the competency map of the CCS-OSCE and of the CNDFME’s in-person OSCE are shown. Although the technical skills and communication skills competences could not be adequately evaluated via an online test, virtual questions could be developed for the remaining competences: anamnesis, physical examination, clinical judgment, prevention and health promotion, and ethical-legal aspects. As per a consensus among all the MS participating in the test and as endorsed by the CNDFME Permanent Commission, the competence of clinical judgment went from representing 20%–35% of points on the test and that of prevention and public health and of ethical/legal aspects and professionalism from 10% to 15%.

Table 1.

Competency map and number of evaluation items of the OSCE of the CNDFME and the CCS-OSCE.

| Competency map | OSCE | CCS-OSCE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage out of the test total | Range of items per competence | Different stations | Percentage out of the test total | |

| Anamnesis | 20 | 50–100 | More than 8, preferably 10 | 20 |

| Physical examination | 15 | 50–90 | Minimum 8 | 15 |

| Technical/procedural skills | 10 | 50–90 | Minimum 3 | 0 |

| Communication skills | 15 | 50–90 | Minimum 8, preferably 10 | 0 |

| Clinical judgment, diagnostic and therapeutic management plan | 20 | 50–90 | Minimum 8 | 35 |

| Prevention and public health | 10 | 20–50 | Minimum 4 | 15 |

| Ethical/legal aspects and professionalism | 10 | 23–50 | Pending | 15 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

OSCE: Objective Structured Clinical Examination; CCS-OSCE: substitute test; MS: medical schools.

Initially, stations that could be done via online platforms were requested from the MS. Forty-four virtual stations classified according to the clinical specialties included in module V of the medical degree curriculum were submitted. In the end, ten stations were selected for each exam day, taking into account the different competences and clinical specialties that had to be evaluated in order to meet the curricular requirements that allow for the degree in medicine to be recognized as a Master’s-level degree. Therefore, it was decided to select clinical cases from gynecology (n = 1), pediatrics (n = 1), psychiatry (n = 1), surgery and orthopedic surgery (n = 2), internal medicine (n = 3), and primary care (n = 2).

Testing the CCS-OSCE

A trial run of the CCS-OSCE was conducted on May 16, 2020, which was three or five weeks before the students’ test day. It consisted of an initial station and three simulated station and was designed so that the student could have examples of the questions he or she would find in the CCS-OSCE stations. It was held on a Saturday afternoon in order to simulate the pressure of a simultaneous common examination on the IT services of each MS’s virtual platform.

A total of 2829 students participated. The test began with a station that contained a welcome video, an explanation of what the test consists of, and that it may contain questions on ethics. Next, four stations appeared sequentially. Once the trial run was finished, the possibility of repeating the last station on subsequent days was offered so that students could familiarize themselves with the types of questions. The duration of the test was about 30 min. Thirteen MS conducted the test on the Moodle platform, two on Sakai, and one on Blackboard.

Terms used in creating the CCS-OSCE

The terms used in creating the CCS-OSCE are defined as follows:

-

1)

Station: group of questions about a clinical case.

-

2)

Question: prompt presented to the student on the screen with a variable number of evaluable and neutral items that, once completed, was submitted and could not be changed. In the majority of questions on the anamnesis and physical examination, the possibility of verification was added: this allowed the student to view the patient’s response to what was asked in the anamnesis in text format or as an image or video in the case of examinations.

-

3)

Evaluable items: elements that were asked about and able to be positively or negatively scored.

Results

Administration of the CCS-OSCE

The CCS-OSCE was held on two dates: June 6 and June 20, 2020. Thirteen MS with 2463 students participated on the first day and three MS with 366 students on the second day. The test started simultaneously in all MS at 7:00 p.m. The CCS-OSCE was designed with the same cases, the same questions, and the same weighting of competences. In Table 2 , the universities, virtual platforms used, and number of students are shown.

Table 2.

Medical schools which participated in the CCS-OSCE.

| University | Number of students |

Virtual platform | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 16 | June 6 | June 20 | ||

| Alfonso X el Sabio, Madrid | 125 | 125 | Moodle | |

| Autónoma de Barcelona | 267 | 267 | Moodle | |

| Cádiz | 104 | 104 | Moodle | |

| Católica de Murcia | 86 | 86 | Sakai | |

| Córdoba | 125 | 125 | Moodle | |

| La Laguna | 155 | 145 | 10 | Moodle |

| Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | 123 | 123 | Moodle | |

| Málaga | 173 | 173 | Moodle | |

| Miguel Hernández de Elche | 128 | 128 | Moodle | |

| Murcia | 207 | 207 | Sakai | |

| País Vasco | 280 | 280 | Moodle | |

| Rey Juan Carlos | 137 | 137 | Moodle | |

| Rovira i Virgili | 10 | 10 | Moodle | |

| Salamanca | 216 | 214 | 2 | Moodle |

| Santiago de Compostela | 375 | 375 | Moodle | |

| Sevilla | 318 | 318 | Blackboard | |

| Total | 2829 | 2463 | 366 | |

Each CCS-OSCE from June 6 and June 20, 2020 presented different situations, though they shared four stations: two with the same clinical case content and the other two with the same initial situation but with a different clinical case (Table 3 ). Students were convened 30 min before the start of the test. The test started with station 0, or the presentation station, followed by ten stations and, to finish, there was a satisfaction survey regarding the test.

Table 3.

CCS-OSCE stations on June 6, 2020.

| Area module V/specialty | Anamnesis |

Physical examination |

Clinical judgment |

Prevention and public health |

Ethical/legal aspects and professionalism |

Total |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialtya | NQ | D | NEI | P | NEI | P | NEI | P | NEI | P | NEI | P | NEI | P |

| Gynecology (1) | 10 | 12 | 8 | 24 | 3 | 19 | 2 | 20 | 4 | 32 | 1 | 5 | 20 | 100 |

| Pediatrics (1) | 10 | 12 | 14 | 25 | 18 | 50 | 6 | 25 | 35 | 100 | ||||

| Psychiatry (1) | 6 | 12 | 5 | 20 | 4 | 40 | 6 | 30 | 4 | 10 | 19 | 100 | ||

| Surgery and orthopedic surgery (2) | 19 | 24 | 12 | 32 | 15 | 25 | 38 | 111 | 9 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 74 | 200 |

| Internal medicine (3) | 31 | 36 | 21 | 65 | 13 | 100 | 16 | 85 | 5 | 30 | 2 | 20 | 57 | 300 |

| Primary care (2) | 32 | 24 | 18 | 30 | 6 | 25 | 32 | 145 | 56 | 200 | ||||

| Total, NEI, and points | 108 | 120 | 78 | 196 | 35 | 184 | 86 | 321 | 23 | 119 | 39 | 180 | 261 | 1000 |

| CNDFME proposal | 100 | 120 | 50 | 200 | 50 | 150 | 50 | 350 | 20 | 120 | 23 | 180 | 193 | 1000 |

The clinical cases on June 6 were: gynecology (vaginal itching), pediatrics: (respiratory illness), psychiatry (psychiatric interview), surgery and orthopedic surgery: (polytrauma and digital rectal exam), primary care (X assault_injury report and right to information), medicine (lower back pain, facial paralysis, and abdominal distention), primary care (X assault_injury report and right to information).

The clinical cases from June 20 were: gynecology (pelvic floor), pediatrics (exanthem), psychiatry (psychiatric interview), surgery and orthopedic surgery (rear-end collision and digital rectal examination), medicine (red eyes, facial paralysis, and sarcoidosis), primary care (cardiovascular risk and right to information).

NQ: number of questions; NEI: number of evaluable items; D: duration of the station; P: points.

In parenthesis: the number of stations per specialty and the clinical cases.

The CCS-OSCE was designed so that each student would complete the stations in a different sequence (50 different variations) to dissuade copying or sharing information. Each station lasted 12 min. The stations opened when the previous station was turned in. If the student did not finish in the allotted 12 min, the station was automatically turned in and exited and the student’s next station according to his or her particular sequence started. The maximum total duration of the test was 120 min. Within each station, the questions were presented sequentially and returning to previous questions was not allowed.

Composition of the CCS-OSCE

On June 6, 2463 students from 13 MS took the exam. The ten stations included three from internal medicine; two from primary care; two from surgery and orthopedic surgery; and one each from gynecology, pediatrics, and psychiatry. The number of questions per station ranged from six to 21, which corresponded to a mean of 1.1 min per question. The total number of evaluable items was 261. Anamnesis was included in nine stations, physical examination in five, clinical judgment in nine, prevention and health promotion in five, and ethical-legal aspects in six. Of the ten stations, almost all contained the five areas of competence evaluated but with a different weighting. Table 3 shows the cases, number of points, and number of evaluable items in all the competences as well as the CNDFME’s proposal for the CCS-OSCE.

On June 20, 2020, 366 students from three MS and some students from other MS who were not available on June 6 took the test. Of the ten stations, four were the same clinical cases as on June 6, 2020: two were identical and two had the same initial situation (right to information and facial paralysis) but with a different course. Six cases were new (Table 3 footer). On this test, the areas of competence were similar to the previous test.

Type of stations and questions

Each station had an initial situation that presented the context of the clinical case. Then there was a set of instructions on the tasks and the general content of the questions that had to be answered. All stations had one or more questions with images and several included a video.

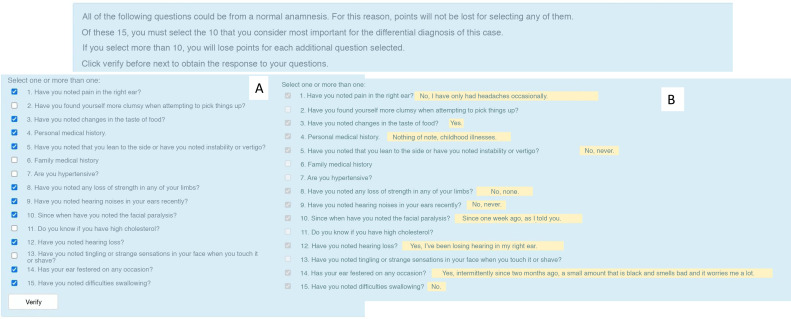

The majority of anamnesis questions were multiple choice with multiple responses, with each item weighted differently. According to the possibilities offered by the platform, the questions included specific feedback, showing the student the patient’s response to the selected items (Moodle) or showing a brief summary in the other two platforms (Fig. 1 A and B).

Figure 1.

Example of a question with feedback to evaluate anamnesis competence used in the CCS-OSCE.

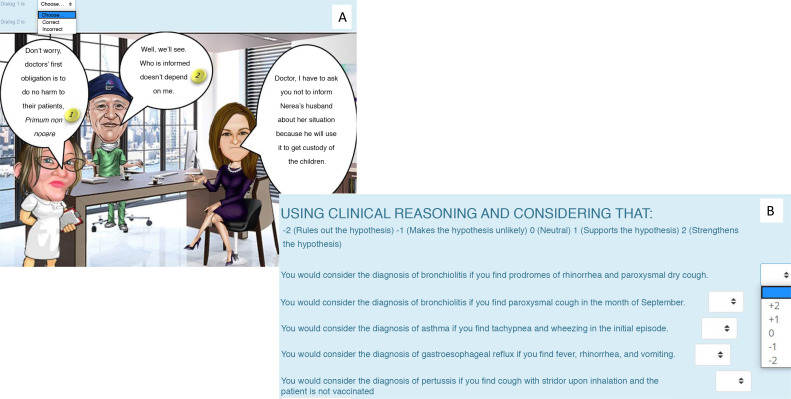

A primary care station was created regarding the right to information, with comic strips and binary questions (correct or incorrect) on ethical aspects (Fig. 2 A). A significant percentage of the clinical judgment questions were script-type reasoning or organization of clinical knowledge into concept maps (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Example of a question to evaluate in (A) cartoon-type ethical competence and in (B) to evaluate script-type clinical judgment competence used in the CCS-OSCE.

Satisfaction survey

The majority of the MS included a satisfaction survey at the end as station 11. Eight schools conducted a common survey on Moodle which consisted of 60 questions (from five to ten possible responses) (see Supplementary material). In a preliminary analysis of the 1437 survey responses, regarding the items that analyzed the general parameters, the majority of students were satisfied, very satisfied, or extremely satisfied with the trial run.

Regarding the test evaluated, the majority of students (52%) indicated that they had a fairly high level of stress beforehand. Despite that, they evaluated as adequate or better the prior information received (70%), the test day organization (83%), the preparation received during their degree (67%), the prior knowledge they had acquired (88%), and the type of medical problems presented compared to the content seen during the degree (76%). Most considered the test to be a good learning experience (75%).

Discussion

This innovative experience allowed for integration and interdisciplinary work among the various MS in the preparation of a joint test that, though we acknowledge it is not the same as the traditional OSCE, has allowed for evaluating a large part of the competences the OSCE must contain in order to be recognized by the CNDFME.

The CCS-OSCE, as designed and described in this article, is a strategy that can be used in upcoming years and can be administered as part of the CNDFME’s OSCE test. It is recommended that the CNDFME’s OSCE test have between 16 and 20 stations with six to eight simulated patient encounters and three to five skills stations5.

In the future, one possibility is for the CNDFME’s OSCE test to be done in two parts: one part with 12 stations in the form of standardized simulated patient encounters and/or skills and procedures stations and a second part of eight to 12 stations, like this year’s CCS-OSCE, in which all students are evaluated using the same clinical cases and, simultaneously, on the competences described in this article.

If this two-part model were to be implemented, our system would be more similar to two components of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE). The CNDFME’s OSCE test would be similar to the USMLE’s Step 2 CS Clinical Skills, in which simulated patient encounters are presented for 12 different clinical cases, and the CCS-OSCE would be equivalent to Step 3 CCS Computer-based Case Simulation, in which the candidate faces computer-simulated clinical cases11, 12. This may facilitate the recognition of our curriculum in accreditation in the USA.

In addition, in upcoming years, this academic year’s experience allows us to also approach administering multiple-choice tests similar to the exam for resident physicians. These are similar to the USMLE’s Step 2 CK Clinical Knowledge and Step 3 MCQ multiple-choice questions. Furthermore, we can now simultaneously administer them using these platforms.

In order to avoid mass travel during the COVID-19 era as well as the necessary close contact with simulated patients, Step 2 CS was canceled this academic year in the United States of America as well as in Spain. The USMLE established a collaboration with 29 schools that served as centers for the virtual Step 1 and Step 2 CK examinations13.

As a consequence of COVID-19, adaptation of the OSCE to the virtual environment also proliferated in Europe14, 15. It is very possible that this will become common practice in the final evaluation of medical students and students from other health science disciplines who take the OSCE as part of their degree.

It should be noted that this type of comprehensive test, beyond the conventional resident physician multiple-choice test, was able to be created thanks to the availability of online educational platforms such as Moodle, Blackboard, and Sakai16, which are the leading platforms for online medical education17.

The clinical cases developed for the evaluation are a highly valuable training tool in the learning process; indeed, training with virtual cases may soon become a widespread teaching tool18, 19. In the survey, the students themselves considered the test to be a good learning experience.

One limitation of the CCS-OSCE is that it does not evaluate areas of competence that are essential in clinical practice, such as communication and technical skills, which are among the key competences for a physician during the anamnesis and examination. Performing these tasks on a standardized simulated patient is not the same as a multiple-choice exercise, even if it is a multiple-choice question with specific feedback on the items. An anamnesis and examination of a patient are also essential for evaluating communication.

In upcoming years, when we have an evaluation of the same students on competences that are common to both the patient examination and the CCS-OSCE, we may be able to compare them to determine what similarities and differences can be found.

A second limitation of the CCS-OSCE is that the student body’s opinion was not available prior to carrying out this project for the digital transformation of the OSCE as a result of the pandemic, though a survey was created to learn their opinion regarding the future.

Lastly, MS’ participation in the tests required agreements with students and schedule changes that led to only half of MS in Spain participating in the CCS-OSCE in 2020. However, in 2021, nearly all will participate and in 2022, we hope that all can include it in their schedule before beginning the academic year.

Conclusions

The CCS-OSCE made it possible to bring together the various medical schools and carry out interdisciplinary work in a crisis situation such as the one lived through. This allowed for creating a OSCE test that meets the requirements of a level 3, or Master’s degree level, qualification according to the Spanish Qualifications Framework for Higher Education.

In addition, the CCS-OSCE may be more similar to the USMLE’s Step 3 CCS and the CNDFME’s OSCE could be equivalent to Step 2 CS. This may facilitate equivalence between a medical degree in Spain and the United States of America in upcoming years.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work had no funding sources.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of the CNDFME for allowing for the creation of an innovative tool for the CNDFME’s OSCE test as well as the entire team of Deans and the coordinators of the OSCE test from all the MS who participated in this trail-blazing, unifying experience.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: García-Seoane JJ, Ramos-Rincón JM, Lara-Muñoz JP. Cambios en el examen clínico objetivo y estructurado (ECOE) de las facultades de Medicina durante la COVID-19. Experiencia de una ECOE de casos-clínicos computarizados simulados (ECOE-CCS) conjunta. Rev Clin Esp. 2021;221:456–463.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rceng.2021.01.006.

Contributor Information

CCS-OSCE working group of the CNDFME:

Antonio López-Román, Narcís Cardoner-Álvarez, Antonio Lorenzo-Peñuelas, Manuel Párraga-Ramírez, Luis Jiménez-Reina, Emilio J. Sanz-Álvarez, Antonio Naranjo-Hernández, Pedro Valdivielso-Felices, José Manuel Ramos-Rincón, Gracia Adánez-Martínez, Miguel García-Salom, José Vicente Lafuente-Sánchez, Agustín Martínez-Ibargüen, Teresa Fernández-Agulló, Antoni Castro-Salomó, María Consuelo Sancho-Sánchez, Álvaro Hermida-Ameijeiras, and Jesús Ambrosiani-Fernández

Appendix A. Members of the CNDFME’s CCS-OSCE working group (by alphabetical order of the university name)

Antonio López-Román (Universidad Alfonso X el Sabio). Narcís Cardoner-Álvarez (Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona). Antonio Lorenzo-Peñuelas (Universidad de Cádiz). Manuel Párraga-Ramírez (Universidad Católica de Murcia). Luis Jiménez-Reina (Universidad de Córdoba). Emilio J. Sanz-Álvarez (Universidad de La Laguna). Antonio Naranjo-Hernández (Universidad Las Palmas de Gran Canaria). Pedro Valdivielso-Felices (Universidad de Málaga). José Manuel Ramos-Rincón (Universidad Miguel Hernández). Gracia Adánez-Martínez y Miguel García-Salom (Universidad de Murcia). José Vicente Lafuente-Sánchez y Agustín Martínez-Ibargüen (Universidad del País Vasco). Teresa Fernández-Agulló (Universidad Rey Juan Carlos). Antoni Castro-Salomó (Universidad Rovira i Virgili). María Consuelo Sancho-Sánchez (Universidad de Salamanca). Álvaro Hermida-Ameijeiras (Universidad de Santiago de Compostela). Jesús Ambrosiani-Fernández (Universidad de Sevilla).

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Trejo Mejía J.A., Martínez González A., Méndez Ramírez I., Morales López S., Ruiz Pérez L.C., Sánchez Mendiola M. Clinical competence evaluation using the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in medical internship at UNAM. Gac Med Mex. 2014;150:8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harden R.M., Stevenson W.M., Doynie W., Wilson G.M. Assessment of clinical competence using an objective structured examination (OSCE) Br Med J. 1975;1(5955):447–451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5955.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regehr G., Freeman R., Robb A., Missiha N., Heisey R. OSCE performance evaluations made by standardized patients: comparing checklist and global rating scores. Acad Med. 1999;74 10 Suppl:S135–S137. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199910000-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sloan D.A., Donelly M.B., Schwartz R.W., Strodel W.E. The objective structured clinical examination. The new gold standard for evaluating postgraduate clinical performance. Ann Surg. 1995;222:735–742. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.García-Estañ López L. Prueba Nacional de Evaluación de Competencias Clínicas de la Conferencia Nacional de Decanos de Facultades de Medicina de España. FEM. 2013;16 Supl 3:S1–S70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.ORDEN ECI/332/2008, de 13 de febrero, por la que se establecen los requisitos para la verificación de los títulos universitarios oficiales que habiliten para el ejercicio de la profesión de Médico. Boletín Oficial del Estado. 2008;40:8351–8354. https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2008/02/15/pdfs/A08351-08355.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kronfly Rubiano E., Ricarte Díez J.I., Juncosa Font S., Martínez Carretero J.M. Evaluation of the clinical competence of Catalonian medicine schools 1994–2006. Evolution of examination formats until the objective and structured clinical evaluation (ECOE) Med Clin. 2007;129:777–784. doi: 10.1157/13113768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García-Puig J., Vara-Pinedo P., Varga J.A. Implantación del Examen Clínico Objetivo y Estructurado en la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Educ Med. 2018;19:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.edumed.2017.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos J.M., Asunción Martínez-Mayoral M., Sánchez-Ferrer F., Morales F., Sempere T., Belinchón I., et al. Análisis de la prueba de Evaluación Clínica Objetiva Estructurada (ECOE) de sexto curso en la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche. Educ Med. 2019;20:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.edumed.2017.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millán Núñez-Cortes J. Educación médica durante la crisis por Covid-19. Educ Med. 2020;21:157. doi: 10.1016/j.edumed.2020.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali J.M. The USMLE step 2 clinical skills exam: a model for OSCE examinations? Acad Med. 2020;95:667. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouyang W., Harik P., Clauser B.E., Paniagua M.A. Investigation of answer changes on the USMLE® step 2 clinical knowledge examination. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:389. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1816-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Completes first testing event with medical school support. USMLE. 2020;3:202. https://covid.usmle.org/announcements/usmle-completes-first-testing-event-medical-school-support [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donn J., Scott J.A., Binnie V., Bell A. A pilot of a Virtual Objective Structured Clinical Examination in dental education. A response to COVID-19. Eur J Dent Educ. 2020;00:1–7. doi: 10.1111/eje.12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara S., Foster C.W., Hawks M., Montgomery M. Remote assessment of clinical skills during COVID-19: a virtual, high-stakes, summative pediatric Objective Structured Clinical Examination. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20:760–761. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbert C., Velan G.M., Pryor W.M., Kumar R.K. A model for the use of blended learning in large group teaching sessions. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:197. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Memon A.R., Rathore F.A. Moodle and Online Learning in Pakistani Medical Universities: an opportunity worth exploring in higher education and research. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68:1076–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig C., Kasana N., Modi A. Virtual OSCE delivery: the way of the future? Med Educ. 2020;54:1185–1186. doi: 10.1111/medu.14286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang H.W., Kim K.J. Use of online clinical videos for clinical skills training for medical students: benefits and challenges. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:56. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.