Abstract

Background

Incidentally diagnosed terminal ileitis [IDTI] has been reported among asymptomatic persons undergoing non-diagnostic colonoscopy. The purpose of our study was to determine the prevalence and long-term outcomes of asymptomatic terminal ileitis.

Methods

We performed a systematic review using three biomedical databases [Medline, Embase, and Web of Science] and relevant scientific meeting abstracts. We identified observational studies that reported the prevalence of IDTI in adults undergoing screening or polyp surveillance colonoscopy and/or the long-term outcomes of such lesions. A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted to determine the pooled prevalence rate of IDTI. The progression of IDTI to overt Crohn’s disease [CD] was also described.

Results

Of 2388 eligible studies, 1784 were screened after excluding duplicates, 84 were reviewed in full text, and 14 studies were eligible for inclusion. Seven studies reported the prevalence of IDTI in 44 398 persons undergoing non-diagnostic colonoscopy, six studies reported follow-up data, and one study reported both types of data. The pooled prevalence rate of IDTI was 1.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.1–21.8%) with significant heterogeneity [I2 = 99.7]. Among patients who had undergone non-diagnostic colonoscopy and had follow-up data [range 13–84 months reported in five studies], progression to overt CD was rare.

Conclusions

IDTI is not uncommon on non-diagnostic colonoscopies. Based on limited data, the rate of its progression to overt CD seems low, and watchful waiting is likely a reasonable strategy. Further long-term follow-up studies are needed to inform the natural history of incidental terminal ileitis, factors that predict progression to CD, and therapeutic implications.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel diseases, Crohn’s disease, terminal ileitis, incidental, asymptomatic, prevalence, progression, meta-analysis

1. Background

Colonoscopy for colorectal cancer [CRC] screening is recommended consistently for average-risk persons ≥ 50 years of age, and increasingly for those ≥ 45 years of age,1,2 and for surveillance as needed.3The proportion of persons undergoing endoscopies for CRC screening in the USA has increased from 38.9% in 2000 to 62.6% in 2009 in adults aged ≥ 50 years,4 and continues to rise. Similarly, CRC awareness and screening colonoscopies are increasing in other parts of the world.5,6 With routine use of non-diagnostic colonoscopy for screening and surveillance indications, incidentally diagnosed terminal ileitis [IDTI] may be identified with increasing frequency in otherwise healthy and asymptomatic persons. How frequently IDTI is found on non-diagnostic colonoscopy is uncertain. In addition, the clinical implications of IDTI are unknown and there are no clear data on long-term outcomes.

The purpose of this study was to describe the prevalence of IDTI in individuals undergoing non-diagnostic colonoscopy and to characterise long-term outcomes, including progression to overt CD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study identification

Identification and retrieval of studies was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA] statement.7 A comprehensive search strategy, which employed both subject headings and keywords, was run in MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid, and Web of Sciences databases from the date of database inception though June 12, 2019. We hand-searched relevant meeting abstracts that were not indexed in the above databases from the past 5 years. We also searched references of all included studies, as well as pertinent reviews. The full search query for all biomedical platforms is available in Appendix A available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online. Search results were exported and de-duplicated into the Covidence platform.8 The review protocol is registered with PROSPERO [CRD42019138597].

2.2. Eligibility criteria

We included observational studies [cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort] that reported the prevalence of IDTI or long-term outcomes of IDTI found on colonoscopy for colorectal cancer [CRC] screening or colorectal polyp surveillance. We applied a filter for observational studies, adapted from the Observational Studies search filter developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN].9 We also included colonoscopies done following a positive faecal occult blood test [FOBT] or faecal immunochemical test [FIT] if these were done for colon cancer screening in otherwise asymptomatic persons. Study designs that did not fit this description were excluded. We excluded patients who underwent colonoscopy for any symptom such as abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, diarrhoea, weight loss, or for evaluation of anaemia or abnormal imaging. If studies reported data on both non-diagnostic and diagnostic colonoscopy, we included only the former subset of patients. IDTI was defined as any macroscopic erythema, erosion, ulceration, or non-specific inflammation noted on terminal ileal intubation. Microscopic evidence of inflammation was part of the IDTI definition in some, but not all studies.

If multiple studies reported data from the same cohort, we included the most recent study, the one with the longest duration of follow-up, or the one with the largest sample size, in this order of priority. Studies published in a language other than English were excluded.

2.3. Study selection and data abstraction

Study selection and data extraction were performed by three investigators [MA, MBM, RU] independently using the Covidence platform.8 Any conflict during abstract or full-text screening was resolved by review of the pertinent study jointly, with an additional arbiter when needed. Data were extracted into REDCap per the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group’s template.10 The following elements were recorded: the name and year of the study, the country and region where it was conducted, study period and design, definition of IDTI, the size of the overall cohort and the subset of eligible patients when applicable, number of IDTI cases, follow-up data including progression to overt CD [per study definition], resolution of IDTI, variables associated with progression, and interpretation.

2.4. Risk of bias and study quality

The risk of bias and quality of studies were evaluated by two investigators independently [MA, MBM], and jointly in case of discrepancy, using either the cohort or modified cross-sectional studies instrument of the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale [NOS].11,12 Studies were evaluated in three domains: selection, comparability, and outcome, and were awarded a maximum of four [five if cross-sectional], two, or three points, respectively. A total score of seven or higher indicated a high-quality study.

2.5. Qualitative and quantitative analysis

We conducted a random-effects meta-analysis to determine the pooled prevalence rate of IDTI, with 95% confidence intervals [CI]. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 score. Meta-analysis was performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software [version 3, Biostat, Inc.]. Reported data on long-term outcomes were limited and heterogeneous, and in several studies were not differentiated by indication for colonoscopy [non-diagnostic versus diagnostic], which precluded meaningful quantitative analysis. Therefore, a qualitative synthesis of data was performed to describe long-term outcomes of patients with IDTI and, when available, variables associated with progression to overt CD.

3. Results

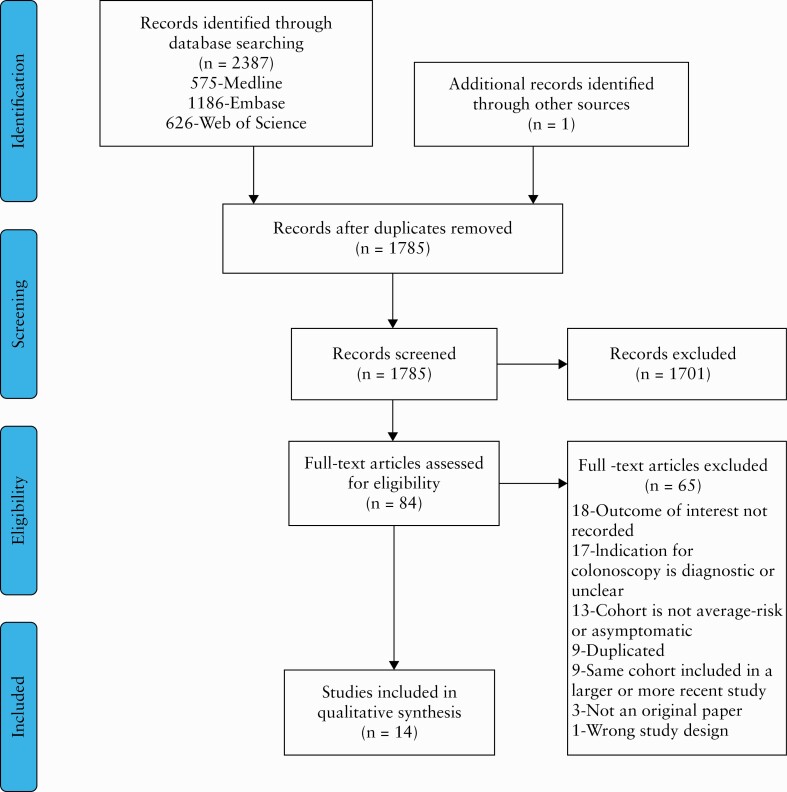

We identified a total of 2388 eligible studies upon execution of our search strategy in all relevant platforms, and one study on hand-searching of meeting abstracts, of which 1785 remained after excluding duplicates [Figure 1]. Of these, 1701 were excluded based on title and abstract review. The remaining 84 studies were reviewed in full and 14 studies met inclusion criteria. Of these, eight were peer-reviewed manuscripts and six were meeting abstracts. Seven studies reported the prevalence of IDTI in 44 398 persons undergoing non-diagnostic colonoscopy [Table 1]. Eight studies reported follow-up data. Of these, one study reported both prevalence and follow-up data13 [Table 2]. Using the NOS, one study was awarded 7 points, indicative of its high quality,13 and the remaining 13 studies were awarded ≤ 6 points [Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online].

Figure 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA] diagram.

Table 1.

Studies reporting the prevalence of incidentally diagnosed terminal ileitis.

| Author | Study location | Study period | Study design | IDTI endoscopic criteria [histological criteria] | Total sample size | Mean age [years] ± SD | Total n included in the meta-analysis | Number with IDTI | Prevalence of IDTI [%] | NSAID use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meral M et al. | Dokuz Eylul University Hospital, Turkey | 2/2014 and 6/2015 | Cross-sectional | Hyperaemic/oedematous mucosa, aphthous ulcer or erosion, ileal ulcer, polypoid or granular appearance, and miscellaneous [acute ileitis] | 1032 | 55.8 ± 14.3a | 486 | 13 | 2.7 | 4b |

| Melton S et al. | Endoscopy centres across the USA | 1/1/2008– 12/31/2009 | Cross-sectional | Erythema, friability, granularity, erosions, and/or ulcers, other abnormalities such as nodules, nodularity, mucosal abnormalities not otherwise described, or stricture [NR] | 9785 | 46 ± NRa | 758 | 480 | 63.3 | 4a |

| McDonnell M et al. | UK Bowel Cancer Screening Programme | 7/2012‐10/2014 | Cross-sectional | Terminal ileal ulceration [NR] | 327 | NR | 325 | 22 | 6.8 | 5 of 24c |

| Zwas FR et al. | Greenwich Hospital, CT, USA | NR | Cross-sectional | Aphthous ulcers [cryptitis] | 138 | NR | 66 | 1 | 1.5 | NR |

| Rodriguez-Lago I et al. | Basque Country, Spain | 2009–2014 | Retrospective cohort | Erythema, erosions, and ulcers [per ECCO criteria] | 31005 | NR | 31005 | 15 | 0.05 | NR |

| Butcher RO et al. | UK Bowel Cancer Screening Programme | 2/2007‐8/2012 | Retrospective cohort | NR | 5350 | NR | 5350 | 16 | 0.3 | NR |

| Kennedy G et al. | The Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA | 1/1/2002– 12/31/2005 | Retrospective cohort | Ulcerated lesions [NR] | 6408 | 63 ± NR | 6408 | 29 | 0.5 | NR |

ECCO, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation; NR, not reported; IDT, incidentally diagnosed terminal ileitis; ASA, aspirin; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; UK, United Kingdom; CT, Connecticut; MN, Minnesota; SD, standard deviation.

aIn total cohort, including those who underwent both non-diagnostic and diagnostic colonoscopies.

bIn total cohort, composite of ASA/NSAID use, hypersensitivity reaction, and infection.cThe denominator includes the two patients with previously diagnosed Crohn’s disease.

Table 2.

Studies reporting long-term outcomes of incidentally diagnosed terminal ileitis.

| Author | Region where study was conducted | Study period | Study design | IDTI endoscopic criteria [histological criteria] | Total n | Mean age [years ± SD] | Non-diagnostic colonoscopy [n] | IDTI [n] | NSAID use [n] | Median follow-up [range] months | Follow-up over time [n] | Diagnostic criteria for overt CD | No progression of IDTI [n] | Resolution of IDTI [n] | Progression to CD [n] | Persons who were treated [n] | Treatment (n, median duration in months [IQR]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodriguez-Lago I et al. | Basque Country, Spain | 2009‐2014 | Retrospective cohort | Erythema, erosions, and ulcers [per ECCO criteria] | 31005 | NR | 31005 | 15 | NR | 37.5 [25–55]b | 21d | NR | NR | NR | NR | 18d | Oral mesalamine [13, 3 [1–7]], topical mesalamine [1, NR], corticosteroids (8, 4 [1.5–11.7]), thiopurines (3, 15 [13–48]) methotrexate [1, 20] and anti-TNF [1, 23] |

| Bezzio C et al. | Milan, Italy | 9/2013 ‐8/2018 | Retrospective cohort | NR | 2062 | 60.8 ± 7.4a | 2062 | 23d | 0 | 13 [2–59] | 23d | NR | NR | NR | 7d | 3d | Corticosteroids followed by vedolizumab [1, NR], corticosteroids followed by azathioprine [1, NR], 5-aminosalicylates [1, NR] |

| Wang WF et al. | Beijing, China | 2000 and 2005 | Retrospective cohort | Non-specific ulcers [NR] | 7 | 76 ± NR | 1 | 1 | 0 | 84 | 1 | Based on laboratory studies, small bowel imaging, endoscopy, pathology | 1 | NR | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Zhang FB et al. | Zhengzhou, China | 2005‐2010 | Prospective cohort | Isolated terminal ileal lesions [NR] | 34 | NR | 3 | 3 | 0 | NR | 3 | Based on symptoms, endoscopy, pathology | 1 | 2 | 0 | NR | NR |

| Kang YM et al. | Seoul, Republic of Korea | 1/2007 ‐5/2018 | Retrospective cohort | Isolated terminal ileal lesions [non-specific chronic inflammation] | 88 | NR | 64 | 64 | 0 | NR | 81c | NR | NR | NR | 1c | NR | NR |

| Courville EL et al. | Lebanon, NH, USA | 1995 and 2003 | Retrospective cohort | Aphthous ulcers/erosion, deep mucosal ulcers, erythema, nodularity, and exudate [focal or chronic active ileitis] | 29 | 60 ± NR | 14 | 14 | 4 | 63.6 [26.4–122.4] | 14c | Based on endoscopy and pathology | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR |

| Castano R et al. | Medellin, Colombia | NR | Retrospective cohort | Isolated terminal ileitis [NR] | 43 | 53.3c | 9 | 9 | 16c | NR | 9c | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR |

| Siddiki H et al. | Scottsdale, AZ, USA | 2010‐2011 | Retrospective cohort | Ileal ulceration, erosions, nodularity, erythema, cobblestoned appearance [NR] | 32 | 53 ± 15.3c | 11 | 11 | 12c | 38.4 [1–61]c | 32c | Unresolving/worsening inflammation, persistent symptoms, based on colonoscopy, pathology, imaging | NR | NR | 3c | NR | NR |

ECCO, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation; NR, not reported; NA, not applicable; IDTI, incidentally diagnosed terminal ileitis; ASA, aspirin; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; CD, Crohn’s disease; NH, New Hampshire; AZ, Arizona;TNF, tumour necrosis factor; SD, standard deviation.

aIncluding both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients.

bInterquartile range.

cIn total cohort, including those who underwent both non-diagnostic and diagnostic colonoscopies.

dIncludes those with lesions in intestinal segments besides the terminal ileum.

3.1. IDTI prevalence

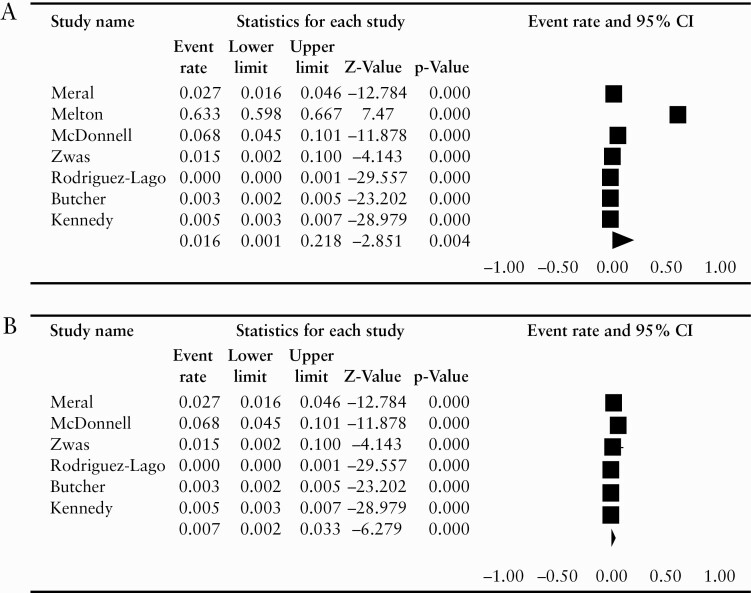

Of the seven studies reporting IDTI prevalence, four were cross-sectional14–17 and three were retrospective cohort studies.13,18,19 One study reported the incidental diagnosis of all CD, including colonic disease,20 and we excluded this from the quantitative analysis of IDTI prevalence. Out of a total of 44 398 persons who underwent non-diagnostic colonoscopy, 576 persons were found to have IDTI. The total number of persons undergoing non-diagnostic colonoscopy in each study varied between 66 and 31 005, and the prevalence rate of IDTI varied between 0.04% and 6.77% in all studies but one. The diagnostic criteria for IDTI varied across studies, but macroscopic erosions or ulcers were included in most. Histological findings were reported in two of seven studies. Melton et al. reported a prevalence rate of 63.3%,15 which is significantly higher compared with other studies. The pooled prevalence of IDTI was 1.6% [95% CI 0.1–21.8%], with significant heterogeneity [I2 = 99.7]. On repeating the analysis after excluding the Melton study, we found the pooled prevalence of IDTI was lower, but it was still associated with considerable heterogeneity [pooled prevalence 0.7%, 95% CI 0.2–3.3%, I2 = 98.1%, Figure 2a and b]. Similarly, whereas the funnel plot and Egger’s regression intercept indicated significant bias when including all studies, this was not the case upon exclusion of Melton et al. study [Supplementary Figure 1, available as Supplementary data at ECCO-JCC online, with Egger’s regression intercept -23.6 and 0.27, respectively].

Figure 2.

Forest plot [a] including all studies; [b] excluding Melton et al. study.

3.2. Long-term outcomes of IDTI

A total of 147 persons with asymptomatic terminal ileitis in eight studies had long-term follow-up data. Follow-up duration was reported in five studies and ranged between 13 and 84 months.13,20–23 In the four studies that reported on diagnostic work-up for overt CD,21–24 the diagnosis was based on varying combinations of clinical, blood-based biomarkers, endoscopic, histological, and imaging findings, and was specified in only one study as worsening or lack of resolution of these findings.21 Below, we summarise the overall findings of each study that reported long-term outcomes of IDTI and granular details are reported in Table 2.

In the study by Rodriguez-Lago et al., of 21 patients including those with IDTI and CD-like features in other ileocolonic segments, six developed diarrhoea after a median of 4 (interquartile range [IQR] 1–9) months; 18 of 21 patients were treated, although most of them before development of symptoms. The three persons who were not treated continued to remain asymptomatic.13 Temporal change in endoscopic findings was not reported in this study.

Bezzio et al. reported findings consistent with CD in 23 people, among whom a definitive diagnosis of CD was made in seven [six male, mean age 61.3 +/- 7.1 years] on follow-up for a median of 13 [range 2–59] months.20 These included ileal [n = 3], ileocolonic [n = 1], and colonic [n = 3] inflammation.

Wang et al. reported seven cases of small bowel ulcers on ileocolonoscopy or enteroscopy, including those who underwent both non-diagnostic and diagnostic colonoscopies. One person, a 76 year-old man, was diagnosed with incidental lesions on surveillance colonoscopy, which were persistent but asymptomatic with no treatment over a 7-year follow-up.23

In the study by Zhang et al., of 34 patients with isolated terminal ileal lesions, the indication for colonoscopy was non-diagnostic in three patients.24 Of these three, TI lesions resolved in two patients within 5 years, and persisted in one with no significant change over 3 years.

In the study by Kang et al., the proportion of the cohort [n = 88] that had IDTI is not clear as the investigators included those who underwent both non-diagnostic [n = 24] and diagnostic colonoscopy [n = 64].25 After excluding patients who were diagnosed with overt CD [n = 5] and tuberculosis [n = 2] on initial colonoscopy, among the remaining 81 patients, lesions resolved in 58 patients, were present and did not progress in 23 patients, and progressed to CD in one patient.

In the study by Courville et al., of 14 persons who were found to have asymptomatic lesions [12 on non-diagnostic colonoscopy, two on colonoscopy for FOBT-positive stool done for CRC screening], none progressed to overt CD clinically on a median follow-up of 5.3 [range 2.2 to 10.2 years].22 Of six persons who had a second endoscopy and biopsy on follow-up, these were normal in four patients and unchanged in two, both of whom were on daily aspirin.

In the study by Castano et al., of nine persons who underwent screening colonoscopy, none progressed to overt CD on long-term follow up.26

Last, Siddiki et al. reported that of 32 persons all with terminal ileal lesions [non-diagnostic colonoscopy in 11 of 32], three patients progressed to overt CD.21 No factor that predicted the risk of progression of IDTI to overt CD was reported in any study with follow up data.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we quantitatively synthesised the existing literature on the prevalence of IDTI in persons undergoing non-diagnostic colonoscopy, and describe long-term outcomes including progression to overt CD or resolution of lesions. The pooled estimated prevalence of IDTI was 1.6%. Among the studies with follow-up data, the rate of disease progression was low.

The one outlier study [Melton et al.] in which IDTI prevalence was 63% in those undergoing non-diagnostic colonoscopy, contributed to significant heterogeneity, as noted on meta-analysis estimates with and without the study.15 Surprisingly, the prevalence of terminal ileal abnormalities in patients undergoing work-up for CD in this study was lower at 39.6%. In the overall cohort, endoscopic ileitis was reported in 1325 [13.5%] patients, ulcers or erosions in 1015 [10.4%] patients, and other abnormalities in 798 [8.1%] patients, although ‘other abnormalities’ are not described further. The NOS grade assigned to this study is 3, which indicates inadequate quality. The authors acknowledge that the rate of IDTI in this study is unexpectedly high. This may be due to referral or selection bias [as these data were obtained from a specialised gastrointestinal laboratory that received specimens from endoscopy centres across the USA], misclassification of colonoscopies as non-diagnostic, or heterogeneity in the definition of IDTI. However, even after exclusion of this study, there is significant heterogeneity in our pooled analysis. This can be due to multiple reasons. The diagnostic criteria for IDTI varied widely across studies, and included microscopic features of ileitis in some, but not all studies. The studies varied in terms of the study populations and centres, leading to diverse baseline characteristics and endoscopy/TI intubation practices. Similarly, differences in study design, inclusion criteria, and reporter bias limit comparability. Last, the outcome IDTI is rare, which is reflected in the lack of robust studies.

In addition, the overall IDTI prevalence in our study is likely to be an underestimate of that in the general population. Non-diagnostic colonoscopy for CRC screening and surveillance is indicated in persons ≥ 45 or 50 years of age. Whereas the number of persons undergoing colonoscopies for colorectal cancer screening in the USA has increased from 38.9% in 2000 to 62.6% in 2009 in adults aged ≥ 50 years,4 and continues to rise, younger persons, in whom CD is diagnosed more frequently, are less likely to be eligible for non-diagnostic colonoscopy. Consistent with this, the patient populations in the current study tended to be older, which may somewhat underestimate the true prevalence of IDTI. Additionally, the detection of IDTI is dependent on the practice of routine TI intubation, which is not a necessary component of routine screening or surveillance colonoscopy and varies widely across providers.27 The increase in procedure time and overall low yield of ileal intubation are likely the main reasons for this practice.27

In some studies, colonoscopies were done after a positive CRC screening using an FOBT or FIT test,13,16,19 but the prevalence of IDTI in these studies is not significantly different from those in which persons underwent screening colonoscopy only. The sensitivity and specificity of non-invasive stool tests, such as occult blood testing, for IDTI diagnosis should be investigated in future studies.

The clinical significance of IDTI remains to be determined. Although IDTI can occur in the context of other aetiologies such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] use and rheumatological diseases,28,29 it could also represent clinically silent or pre-clinical CD.28 Early and asymptomatic CD has been reported in nearly 25% of persons with spondyloarthropathies.30 NSAIDs have been linked with CD incidence and exacerbation.31,32 Whether these lesions represent early CD or transient terminal ileitis due to a secondary aetiology, such as NSAID use, is not clear. NSAID use was reported in a minority of patients in some studies and was an exclusion criterion in others [Table 2]. Low prevalence and lack of predictors of progression further limit our understanding of the natural history of IDTI. None of the studies that reported follow-up of patients with IDTI identified factors predicting progression to overt CD. Interestingly, of those studies that included patients undergoing both non-diagnostic and diagnostic colonoscopy, three reported that presence of abdominal pain at the time of colonoscopy was a predictor of disease progression. This subset of patients is excluded from our study, but further studies to identify symptoms on follow-up of patients with IDTI would be informative. Longitudinal changes in endoscopic and histological findings, inflammatory biomarkers, and cross-sectional imaging findings would also be important in delineating the natural history of IDTI and identifying risk factors for progression to overt CD.

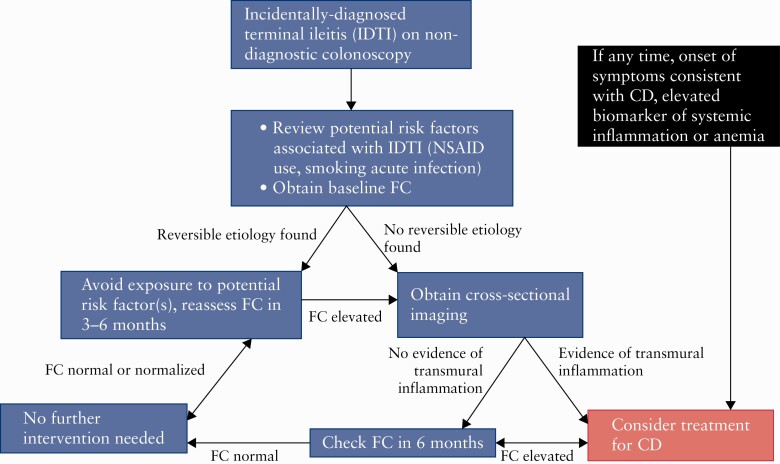

We describe our current practice in approaching IDTI, based on limited data and expert opinion, in Figure 3. In brief, we recommend ruling out reversible causes of IDTI and checking faecal calprotectin [FC]. If no reversible a is found and FC is elevated, we recommend obtaining cross-sectional imaging and repeating FC longitudinally. The majority of these patients can be managed with watchful waiting. However, if there is any concern for the disease being more extensive than IDTI, persistently elevated FC, or the patient develops any symptom or elevated biomarker suggestive of systemic inflammation on longitudinal follow-up, we would consider initiating therapy for CD.

Figure 3.

Proposed management of incidentally-diagnosed terminal ileitis. NSAID,non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; FC, faecal calprotectin; CD. Crohn’s disease.

There are several strengths of our study. We have summarised the existing literature, albeit limited, to report the composite prevalence of IDTI as well as data on long-term outcomes of such lesions and granular description of progression to CD. We report the prevalence of IDTI and its unlikely progression to overt CD, which offers practical clinical guidance to clinicians. Future long-term observational studies are needed to further define prevalence and in particular risk factors for progression of lesions to overt CD, and to understand which patients represent early CD and may warrant early treatment and/or closer monitoring.

We also acknowledge several limitations. This is a meta-analysis of observational studies that are highly heterogeneous, as described above. This limitation is common with meta-analyses and emphasises caution in application of their results to clinical practice and research. However, this is one of the first studies to synthesise the existing literature and draw attention to the paucity of high-quality data on this relevant topic. Our study is limited to those over 45–50 years of age, and lack on data on younger persons limits generalisability. However, due to lack of screening tests in younger patients, this is a limitation inherent to any study on IDTI. Additionally, some studies reported composite long-term follow-up data on terminal ileitis in patients who underwent both non-diagnostic and diagnostic colonoscopy, precluding quantitative analysis. Finally, the impact of NSAIDs on prevalence and progression warrants future long-term follow-up studies.

In summary, in this meta-analysis we report that the prevalence of IDTI in persons undergoing non-diagnostic colonoscopy is low but not infrequent. Based on limited data, the rate of progression to overt CD also appears to be low, and watchful waiting could be a reasonable strategy in such patients. Future studies are needed to identify risk factors for progression to CD and strategies for the best management of IDTI.

Funding

RCU is supported by an NIH K23 Career Development Award [K23KD111995-01A1].

Conflict of Interest

MA receives research support from the Dickler Family Fund, New York Community Trust, and the Helmsley Charitable Trust Fund for SECURE-IBD. NN holds a McMaster University Department of Medicine Internal Career Award and has received honoraria from Janssen, Abbvie, Takeda, Pfizer, Merck, and Ferring. JFC reports receiving research grants from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda; receiving payment for lectures from AbbVie, Amgen, Allergan, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Shire, and Takeda; receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Enterome, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Landos, Ipsen, Medimmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, Tigenix, Viela bio; and holding stock options in Intestinal Biotech Development and Genfit. RCU has served as a consultant and/or advisory board member for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer ;and Takeda; has received research support from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim; and Pfizer.

Author Contributions

MA, MBM: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; SW: search strategy design and execution, data management; NN: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; JFC, RU: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for colorectal Cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016;315:2564–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:250–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2012;143:844–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang DX, Gross CP, Soulos PR, Yu JB. Estimating the magnitude of colorectal cancers prevented during the era of screening: 1976 to 2009. Cancer 2014;120:2893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burr NE, Derbyshire E, Taylor J, et al. Variation in post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer across colonoscopy providers in English National Health Service: population based cohort study. BMJ 2019;367:l6090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Li N, Ren J, et al. ; group of Cancer Screening Program in Urban China [CanSPUC]. Participation and yield of a population-based colorectal cancer screening programme in China. Gut 2019;68:1450–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page MJ, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews 2020. metaArXiv Preprints 2020. doi: 10.31222/osf.io/v7gm2. [DOI]

- 8.Covidence. Better Systematic Review Management 20202020. https://www.covidence.org/home. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- 9.SIGN. Observational Studies Search Filter Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN]. https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/search-filters-observational-studies.docx. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 10.Ryan R, Synnot A, Prictor M, Hill S. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group Data Extraction Template for Included Studies.Melbourne, VIC: La Trobe University, 2020. https://opal.latrobe.edu.au/articles/journal_contribution/Data_extraction_template/6818852. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [NOS] for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2020.

- 12.Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodríguez-Lago I, Merino O, Azagra I, et al. Characteristics and progression of preclinical inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwas FR, Bonheim NA, Berken CA, Gray S. Diagnostic yield of routine ileoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:1441–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melton SD, Feagins LA, Saboorian MH, Genta RM. Ileal biopsy: clinical indications, endoscopic and histopathologic findings in 10,000 patients. Dig Liver Dis 2011;43:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonnell M, Al Badri A, Burningham S, Gordon J. Incidence of endoscopically and histologically confirmed ileal ulceration in a sequential cohort of patients undergoing screening colonoscopy as part of the UK Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:S422–S3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meral M, Bengi G, Kayahan H, et al. Is ileocecal valve intubation essential for routine colonoscopic examination? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;30:432–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy G, Larson D, Wolff B, Winter D, Petersen B, Larson M. Routine ileal intubation during screening colonoscopy: a useful maneuver? Surg Endosc 2008;22:2606–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butcher RO, Mehta SJ, Ahmad OF, et al. Incidental diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in a British bowel cancer screening cohort: a multi-centre study. Gastroenterology 2013;144[Suppl 5]: S630–S1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bezzio C, Arena I, della Corte C, Devani M. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] in a colorectal cancer population screening program. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13[Suppl 1]:S500. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siddiki H, Lam-Himlin D, Pasha SF, Gurudu SR, Leighton JA. Terminal ileitis of unknown significance: long-term follow-up and outcomes in a single cohort of patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110[Suppl 1]: S768–S9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courville EL, Siegel CA, Vay T, Wilcox AR, Suriawinata AA, Srivastava A. Isolated asymptomatic ileitis does not progress to overt Crohn disease on long-term follow-up despite features of chronicity in ileal biopsies. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang WF, Wang ZB, Yang YS, Linghu EQ, Lu ZS. Long-term follow-up of nonspecific small bowel ulcers with a benign course and no requirement for surgery: is this a distinct group? BMC Gastroenterol 2011;11:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang FB, Hao WW, Zhao WG, Zheng C, Chu YJ, Xu F. The analysis of factors associated with progression of isolated terminal ileal lesions. PLoS One 2014;9:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang YM, Kim YS, Woo YM, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of isolated terminal ileal lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;33[Suppl 4]: 552. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castano R, Puerta J, Restrepo J, Escobar J, Ruiz M. Long follow-up of patients with isolated ileal erosions and its relationship with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17[Suppl 1]: S31. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leiman DA, Jawitz NG, Lin L, Wood RK, Gellad ZF. Terminal ileum intubation is not associated with colonoscopy quality measures. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020. PMID: 32003060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greaves ML, Pochapin M. Asymptomatic ileitis: past, present, and future. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006;40:281–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altomonte L, Zoli A, Veneziani A, et al. Clinically silent inflammatory gut lesions in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathies. Clin Rheumatol 1994;13:565–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leirisalo-Repo M, Turunen U, Stenman S, Helenius P, Seppälä K. High frequency of silent inflammatory bowel disease in spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ananthakrishnan AN, Higuchi LM, Huang ES, et al. Aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and risk for Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:350–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Long MD, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Chen W, Anton K, Sandler RS. Role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50:152–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.