Abstract

The extraordinariness of COVID-19 occurred in a world that was completely unprepared to face it. To justify this, sometimes literature proposes positive associations between concentrations of some air pollutants and SARS-CoV-2 mortality and infectivity. However, several of these studies are affected by incomplete data analysis and/or incorrect accounts of spread dynamics that can be attributed to respiratory viruses.

Based on separate analyses involving all the USA states and globally all the world countries suffering from the pandemic, this communication shows that commercial trade seems to be a good indicator of virus spread, being proposed as a surrogate of human-to-human interactions.

The results of this study strongly support the conclusion that this new indicator could result fundamental to model (and avoid) possible future pandemics, strongly suggesting dedicated studies devoted to better investigate its significance.

Keywords: COVID-19 spread, SARS-CoV-2, Air pollution, PM2.5, Commercial trade

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic had impacted the world in 2003, but it resulted relegated to some areas. It was followed by other disease outbreaks (like the H1N1 influenza in 2009), putting in evidence the need for active actions to prevent possible pandemics. However, the resources and efforts devoted to the containment of these past disease outbreaks were limited. This had probably persuaded that also in 2019 the occurrence of a pandemic could have been improbable, then not considered at the same level of concerns of as threats of war, nuclear disaster, terrorism, or global economic instability.

The consequences of SARS-CoV-2 underestimated diffusion are now evident at global level. Currently, the origins, aspects, and main repercussions of the COVID-19 diffusion are at the centre of several studies, because they are fundamental not only to model the pandemic diffusion but also to avoid similar diseases in the future.

However, literature production has shown a gap between the available (and often not complete) data about SARS-CoV-2 spread and efforts to understand and model the outbreak in a complex and fast-moving pandemic. In particular, the discussion about the airborne transmission of respiratory droplets (Greenhalgh et al., 2021) originated by infected people, has alimented the hypothesis of existing mechanisms of virus diffusion other than human-to-human transmission, as the people exposure to air pollutants. For example, the dynamics of an epidemic, which can be expressed by the basic reproduction number R0 (average number of people that an infected individual can infect) has been associated with the PM2.5 exposure levels in USA, but no attention was devoted to the fact that the values of yearly-resolved concentrations of this pollutant were lower than 9 μg/m3 (Chakrabarty et al., 2021).

The negative role of air pollution on humans' health, including the derived respiratory problems, has already been recognized. However, its association with pandemic diffusion needs more rigor and solid scientific analysis (Marquès and Domingo, 2022), to avoid the establishment of dangerous myths (Bontempi, 2020), that may induce people to limit outdoor activities, where the virus has been recognized to be more diluted (in comparison to indoor).

The spread of a virus is dependent on several factors, like for example its transmissibility, the human interactions, the contact rates, the applied restriction measures to limit its diffusion, and the duration of infectiousness.

The use of pollution and/or environmental determinants of spreading to justify the COVID-19 incidence need to define the bonding conditions or specify study limitations, to be sure that confounding influence of the other reported factors are accounted or to clearly declare that they are completely neglected (Villeneuve and Goldberg, 2021). In addition, the geographical border of the study must be selected taking into account the real population exposition, as for example the residential mobility connected to work locations, that often occur when people live in small villages (Villeneuve and Goldberg, 2020). The social, geographical, and economic characteristics of a specific region (or country) can affect the transmission dynamics, which can be basically associated with the main recognized way of virus spread (i.e. people interactions (Villeneuve and Goldberg, 2020)). Moreover, the economic and mobility activities can also be associated to increased air pollution, having in mind that the air quality is a consequence of industrial and residential activities (e.g. residential heating technologies) and mobility (see for example Bontempi and Coccia, 2021). As a result, the attribution of an active role in mechanisms of COVID-19 spread to the air quality may be an indirect consequence of other exposition factors, with the pollution acting as a surrogate for urbanicity, making the association controversial (Heederik et al., 2020).

Indeed, it was recently shown that the mean country PM2.5 concentrations cannot seem to be directly linked to virus diffusion (Bontempi et al., 2020) if several countries are compared.

In this frame, a new recently proposed multidisciplinary approach, that has in the explanation of HIV diffusion in Africa a pioneering example (Oster, 2012), has proposed that commercial trade can be considered an indicator of SARS-CoV-2 diffusion (Bontempi et al., 2021). This was suggested also by other authors reporting that viruses seem to spread faster during economic booms (Adda, 2016). Indeed, the global increase of trade is linked to the economic growth and to an evolution of the economy toward a global dimension, suggesting that commercial trade can represent a surrogate of social interaction (The Economy ebook, 2017), making this parameter suitable to follow a disease dynamic (Bontempi and Coccia, 2021).

This approach was recently validated for COVID-19 not only in a single country (considering all the 107 Italian provinces) (Bontempi and Coccia, 2021), but also at the European level, comparing all the France, Italy, and Spain regions (totally 52 regions) (Bontempi et al., 2021).

The aim of this short communication paper is to propose the use of this indicator in all the studies devoted to investigating the role of pollution (mainly air pollution) in the virus spread diffusion, as a surrogate of social interactions. This is supported by an analysis of cumulated reported COVID-19 cases for all the USA states and globally for all the world countries, discussed based on the newly proposed indicator.

2. Materials and methods

The data used in this work (and their availability) are reported in the following:

-

-

Import and export trade data by country from 2003 to 2017 (the last published data) are available at the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) website: https://wits.worldbank.org/about_wits.html

-

-

United States import and export trade data by country from 2017 to 2020 (the last published data) are available at United States Census Bureau website: https://www.census.gov/about.html

-

-

World detected COVID-19 infection cases (data are updated on July 05, 2021) are available at the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) of the Johns Hopkins University: https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19

-

-

United States detected COVID-19 infection cases and deaths (data are updated on July 02, 2021) can be found at COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) of the Johns Hopkins University: https://github.com/CSSEGISandData

3. Discussion

Almost all the models used to analyse the COVID-19 spread are based on temporal analysis, with limited comparisons discussing the potential COVID-19 spread sources and the possibility to directly compare different cities, regions, states, and countries.

The analysis of a possible correlation between SARS-CoV-2 diffusion and commercial trade data can be applied (for the first time) to all the USA states.

Fig. 1a shows the 2017 International trade data (the sum of the total amount of import and export) expressed in US$, for all the USA states (2017 international trade data are the last available data for all world countries). Fig. 1(b–c) show the geographical distribution of the cumulative COVID-19 detected cases and deaths in the corresponding states of Fig. 1a (on July 02, 2021). An impressive correlation between the geographical distribution of the COVID-19 detected infection cases and the international trade data is evident, demonstrating that for all the USA states the international trade can be considered a strong indicator of COVID-19 spread. The results of Pearson analysis are reported in Table 1 , where also the correlations considering the more recent international trade data available for the USA (2020) are reported, suggesting that the proposed indicator is robust.

Fig. 1.

a) 2017 International trade data (the sum of total amount of import and export) expressed in US$, for all the USA states; b) cumulative detected COVID-19 infection cases in all the USA states (on July 02, 2021); c) cumulative detected COVID-19 deaths in all the USA states (on July 02, 2021).

Table 1.

Pearson correlation (R) between the international trade data (for 2017 and 2020) and detected cases on July 02, 2021, for all the USA States (Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, and District of Columbia are also considered). The Pearson correlation between commercial trade and reported deaths is also shown.

| n = 53 |

Cumulative detected COVID-19 cases on July 02, 2021 |

Cumulative confirmed COVID-19 deaths on July 02, 2021 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| International trade for all the USA states | R (95% CI) | p-value (2 sided) | R (95% CI) | p-value (2 sided) |

| Data of 2017 | 0.933 (0.886–0.961) | 2.93E-12 | 0.863 (0.772–0.919) | 5.08E-17 |

| Data of 2020 | 0.937 (0.893–0.963) | 5.58E-25 | 0.878 (0.797–0.928) | 5.60E-18 |

This may open a question concerning the reasons that can justify the differences in the impact and diffusion of SARS-CoV-2, if compared to previous epidemics.

Comparing the current situation with SARS epidemic, it is fundamental to highlight some differences, that cannot be relegated only to SARS-CoV-2 characteristics (it is a fast-moving pathogen resulting transmissible also with symptoms absence), but that must also consider that the world has changed in the last years, reaching an underestimated globalization level.

Indeed, the current globalization situation is different if compared to 2003 (during the SARS epidemic). For example, data about international commercial trade show that for almost all the world counties, the amount of import and export (evaluated in US$) is doubled comparing 2017 and 2003. Instead, considering the same period, a dramatic increase in international exports occurred in China, with a total value of $2.263 trillion in 2017, which is more than five times higher than the corresponding value of 2003. This makes China, where SARS-CoV-2 originated, the world's major player in international trade supply (Zhang et al., 2020).

Thus, it is important to analyse the variable pattern of the pandemic across countries to be able to globally compare data, to better understand the epidemic diffusion mechanisms and the efficacy of proposed responses.

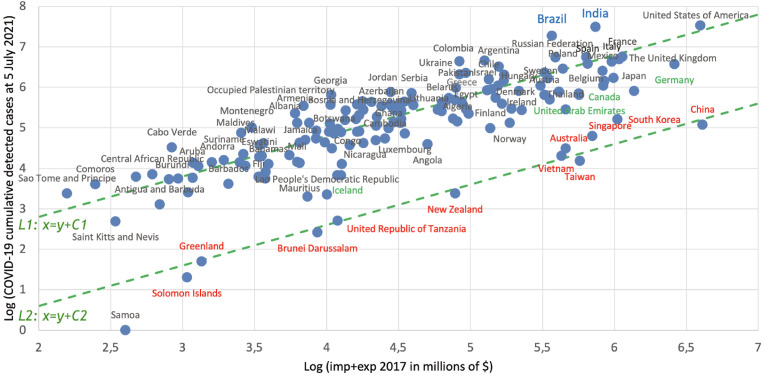

Data about the geographical distribution of the COVID-19 detected infection cases versus the corresponding country's international trade considering all the world are shown in Fig. 2 . In this case, the USA (United States of America) is considered as a single country. These data seem to follow two mains' distributions, considering the proposed x-axis (international commercial trade data expressed in US$), that can be fitted by two linear trends. Countries with higher infection cases can be fitted by L1 line. On the contrary, countries with lower virus spread (if compared to the other countries), can be interpolated by L2 line. L1 and L2 have different intercepts. These behaviours can be analysed in terms of different COVID-19 severity. The countries names, corresponding to data that can be interpolated by L1 are reported in black. It is evident that this data distribution shows a great dispersion, with countries showing higher infection cases (and countries showing lower infection cases) in comparison to the interpolating line. Then it is also possible to highlight countries that can be found on the upper (reported in blue colour) and lower (reported in green colour) limits of this distribution. This allows discussing some differences in the pandemic spread that can be also attributed to the introduction of restriction measures.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative detected COVID-19 infection cases in all the world countries (on July 05, 2021) versus the 2017 international trade data (the sum of the total amount of import and export) expressed in US$. For both axes, the data are reported in a logarithmic scale. Countries distribution with the higher infection cases can be interpolated by L1 line (the names are reported in black colour). On the contrary, countries' distribution corresponding to lower virus spread can be interpolated by L2 line (the names are reported in red colour). L1 and L2 have different intercepts (C1 and C2). Some country's names corresponding to L1 distribution are highlighted: the names reported in blue colour (in the top) indicate countries with higher COVID-19 diffusion (for example Brazil and India) and the names reported in green (in the bottom) indicate some countries that can be also mentioned (for example Germany and Canada). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

In particular, countries with the poorest results in addressing COVID-19 (with the higher infection case numbers) generally denied the potential impact of the pandemic and responded with uncoordinated measures that often were not based on a scientific approach, with the result to delay suitable, effective, and comprehensive actions. As a clear example, Brazil and India represent two of the countries with the worse situation (as supported by literature), being in the upper part of data distribution fitted by L1. Other countries, that can be found in the lower limits of this distribution, are highlighted in green colour in Fig. 2: Canada seemed to better meet the local epidemiological needs, in comparison to other counties (like the USA) due to its flexible decentralized approach (Unruh et al., 2021). Despite its proximity to Italy and France, Germany better managed the first pandemic wave in Europe, due to its quick containment efforts and the availability of a large amount of intensive care beds. Iceland was an example in the quick introduction of a free broad testing and contact-tracing regime and the United Arab Emirates imposed stringent social distancing constrictions (lockdowns, also banning public prayers and celebrations) and impressive disinfection campaigns.

On the bottom part of Fig. 2, a limited number of countries showed lower virus spread, in comparison to the others, supporting the conclusion that they better managed the pandemic (the data are distributed along L2 interpolating line, and the country's name is represented in red). Indeed, Asian and Pacific countries like China, South Korea, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam (Lewis, 2020), generally adopted aggressive containment strategies, often due to the existence of a coordinated and centralized governance structure. For example, Taiwan and Singapore response to the pandemic was prompt and effective: their political authorities chosen to be supported by the technology to ensure a strong transmission monitoring activity. South Korea adopted extensive testing, isolation, contact tracing, and real-time tracking of infective people. New Zealand closed its borders less than three weeks after the first contagious case detection. Australia also imposed early and strict measures to better control transmission, limiting travel non only in the country but also from outside.

Fig. 2 clearly shows in a single graph a message that was already recognized by the scientific community but using different approaches and several evaluation parameters: the countries that responded earlier and aggressively to the pandemic had better outcomes in terms of outbreak diffusion. The best responding countries were able to early introduce suitable measures, acting in a precautionary way, being able to take as example the other countries, like Wuhan where the stringent lockdown restrictions demonstrated the potentialities to buy time and drop the infection.

Finally, it is also interesting to highlight that South Korea and China showing air pollution levels far greater than the USA and Canada (the 2017 PM2.5 mean annual exposition for South Korea and China was respectively 32 and 53 μg/m3 and for the USA and Canada was respectively 7 and 6 μg/m3) (Bontempi et al., 2020), better managed the COVID-19 disease.

4. Concluding remarks

The results presented in this short communication highlight the significant and priority role of human-to-human interactions in the spread of COVID-19, and that they can be modelled by considering a single indicator. This does not exclude the possible secondary role of other factors (for example pollution and/or environmental factors), but an eventual causal effect must be investigated with more rigorous approaches.

The implications of these results can be summarised in the following:

-

-

commercial trade has been demonstrated to be an interesting and promising new indicator to model and understand virus transmission dynamics;

-

-

countries with high commercial interactions result to be more exposed to import and/or export of contagious;

-

-

all the studies aimed to understand the role of pollution and climatic parameters in the virus diffusion, cannot be realised whiteout considering the fundamental role of human-to-human interactions;

-

-

the already published studies discussing the pandemic diffusion on the basis of pollution-to-human transmission mechanism should be reconsidered and revised in accord with the presented study;

-

-

the commercial trade liaison with globalisation should be investigated in further detail, in order to understand their substantial dependence;

-

-

the possibility to identify the potential more vulnerable countries, is fundamental to design suitable strategies and to avoid eventual future pandemics.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares that she has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The graphical abstract was realised with BioRender.com.

References

- Adda J. Economic activity and the spread of viral diseases: evidence from high frequency data. Q. J. Econ. 2016;131:891–941. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjw005. 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E. Commercial exchanges instead of air pollution as possible origin of COVID-19 initial diffusion phase in Italy: more efforts are necessary to address interdisciplinary research. Environ. Res. 2020;188:109775. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E., Coccia M. International trade as critical parameter of COVID-19 spread that outclasses demographic, economic, environmental, and pollution factors. Environ. Res. 2021;201:111514. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E., Vergalli S., Squazzoni F. Understanding COVID-19 diffusion requires an interdisciplinary, multi-dimensional approach. Environ. Res. 2020;188:109814. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E., Coccia M., Vergalli S., Zanoletti A. Can commercial trade represent the main indicator of the COVID-19 diffusion due to human-to-human interactions? A comparative analysis between Italy, France, and Spain. Environ. Res. 2021;201:111529. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty R.K., Beeler P., Liu P., et al. Ambient PM2.5 exposure and rapid spread of COVID-19 in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;760:143391. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Jimenez J.L., Prather K.A., Tufekci Z., Fisman D., Schooley R. Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2021;397:1603–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00869-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heederik D.J.J., Smit L.A.M., Vermeulen R.C.H. Go slow to go fast: a plea for sustained scientific rigour in air pollution research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;56:2001361. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01361-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. Why many countries failed at COVID contact-tracing — but some got it right. Nature. 2020;588:384–387. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquès M., Domingo J.L. Positive association between outdoor air pollution and the incidence and severity of COVID-19. A review of the recent scientific evidences. Environ. Res. 2022;203:111930. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster E. Routes of infection: exports and HIV incidence in sub-saharan Africa. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2012;10:1025–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01075.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Economy Ebook Developed by CORE Project 2017. https://www.core-econ.org/the-economy/index.html

- Unruh L., Allin S., Marchildon G., et al. Health Policy; Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States of America: 2021. A Comparison of Health Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve P.J., Goldberg M.S. Methodological considerations for epidemiological studies of air pollution and the SARS and COVID-19 coronavirus out- breaks. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020;128(9) doi: 10.1289/EHP7411. PMID: 32902328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve P.J., Goldberg M.S. Re: links between air pollution and COVID-19 in England. Environ. Pollut. 2021;274:116576. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Luo J., Zhang C.Y., Lee C.K.M. The joint effects of information and communication technology development and intercultural miscommunication on international trade: evidence from China and its trading partners. Ind. Market. Manag. 2020;89:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]