Abstract

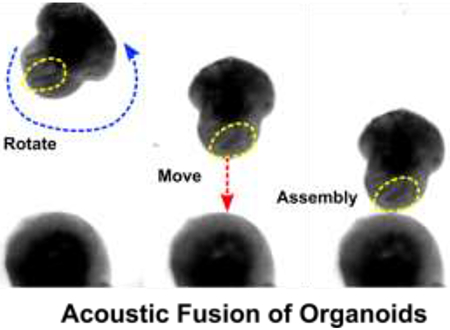

The fusion of human organoids holds promising potential in modeling physiological and pathological processes of tissue genesis and organogenesis. However, current fused organoid models face challenges of high heterogeneity and variable reproducibility, which may stem from the random fusion of heterogeneous organoids. Thus, we developed a simple and versatile acoustofluidic method to improve the standardization of fused organoid models via a controllable spatial arrangement of organoids. By regulating dynamic acoustic fields within a hexagonal acoustofluidic device, we can rotate, transport, and fuse one organoid with another in a contact-free, label-free, and minimal-impact manner. As a proof-of-concept to model the development of the human midbrain-to-forebrain mesocortical pathway, we acoustically fused human forebrain organoids (hFOs) and human midbrain organoids (hMOs) with the controllable alignment of neuroepithelial buds. We found that post-assembly, hMO can successfully project tyrosine hydroxylase neurons towards hFO, accompanied by an increase of firing rates and synchrony of excitatory neurons. Moreover, we found that our controllable fusion method can regulate neuron projection (e.g., range, length, and density), projection maturation (e.g., higher firing rate and synchrony), and neural progenitor cell (NPC) division in the assembloids via the initial spatial control. Thus, our acoustofluidic method could serve as a label-free, contact-free, and highly biocompatible tool to effectively assemble organoids and facilitate the standardization and robustness of organoid-based disease models and tissue engineering.

Keywords: Human Brain Organoid, Organoid Fusion, Acoustofluidics, Neural Circuity, Mesocortical pathway

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Human organoids, or organ-like 3D cultures, are formed through the spontaneous self-organization and differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) or human tissue-derived progenitor cells.1 Human organoid cultures provide a promising platform to recapitulate key histological features of human healthy and diseased organs, holding great potential in organ developmental research, disease modeling, drug screening, and translational medicine. Compared with 2D in vitro cell cultures, the human organoid cultures recapitulate key physiological features and complexity of human tissues and organs. Compared with animal models, human organoids represent human-specific genetics, epigenetics, and transcriptomics.2, 3 So far, a variety of human organoids have been developed for optic cup, intestine, kidney, lung, pancreas, thymus, various types of tumors as well as brain tissues.4–6 Moreover, the fused human organoids have been explored to recapitulate the complete organ makeup or to study inter-organ cross-talks.7–11 For example, brain assembloids, the cultures of fused human brain region-specific organoids, have been generated to model complex cell-cell interactions and neural circuit formation (e.g., cortico-striatal, cortical-thalamic, and cortico-hippocampal circuits) in the human nervous system.12 Additionally, brain organoids can also be fused with glioblastoma spheroids to model tumorigenesis and invasion.13, 14 The fused human organoid models have tremendous potential in etiology and drug development with multi-organ crosstalk modeling including brain-colorectal assembloids to model brain-gut axis, brain-pituitary gland organoids to model neuro-endocrine axis, etc.

Despite the promising applications of current assembloid models, high heterogeneity and variable reproducibility limit its application potentials. Current human organoids have high heterogeneity in size, shape, and spatial distribution of asymmetric features such as neuroepithelial buds in brain organoids.15 Recently, efforts have been made to address the technological challenges in generating robust, reproducible, and reliable human organoid and fused human organoid models. One strategy is to generate standardized human organoids as well as improve the quality control of organoid cultures. For example, the Pașca group developed a directed differentiation method for the reliable generation of human cortical organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) by modulating the differentiation protocol.16 Besides tighter control of differentiation fate with defined morphogens, bioengineering methods have shown great potential to optimize organoid culture and reduce heterogeneity.17–19 Ingber group has developed lung and intestine-on-a-chip devices for standardized organ model culture to recapitulate tissue-to-tissue interfaces.20, 21 Lancaster group has demonstrated that using microfilament as a scaffold for organoid culture can improve tissue architecture and reduce heterogeneity.22 Lutolf and his colleagues employed micro-engineered devices, controlled mechanical cues from ECM, patterned growth factors, and automated systems for high throughput generation of organoids with reduced heterogeneity.23–26 Qin research team developed micropillar arrays and droplet microfluidics for high throughput organoid fabrication and perfusable microfluidic chips for organoid culture.27–29 Ming group developed 3D printed mini-bioreactors for scalable brain organoid culture with reduced heterogeneity.30 Recently, we reported a one-stop microfluidic culture method that minimized cerebral organoid size-variation and hypoxia.31 Thus, the generation of standardized organoids becomes an important research area in the field of organoids and regenerative medicine.

In addition to reduce intra organoid heterogeneity, current assembloid models fuse two or more organoids with random orientation disregarding the distribution of asymmetric features such as neuroepithelial buds in brain organoids. The neuroepithelial buds, or ventricular zone/subventricular zone (VZ/SVZ), are unique brain tissue structures that dictate the distribution of cell types, the arrangement of development layers, and the gradient of growth factors, enabling the direction of the neuron projection.32 It is known that the assembloids with randomly spatially-arranged neuroepithelial buds develop variable neuron projections. 10, 33, 34 Thus, we hypothesized that the assembloid’s neuron projection can be regulated by controlling neuroepithelial buds’ spatial arrangement during the initial fusion of organoids. To test this hypothesis, a versatile and robust tool is required for the controllable fusion of cell spheroids and/or organoids. So far, several attempts were reported on the arrangement and fusion of cell spheroids and/or organoids using microfluidic and engineering approaches. The most commonly used cell spheroid fusion methods employ gravity to get two or more cell spheroids in contact with each other at nonadherent wells with curved bottoms or hanging drops.35, 36 Recently, Tomasi and coworkers have developed a microfluidic droplet array for the formation and culture of one cell spheroid per droplet, and the merging of two cell spheroids via the droplet trapping, pairing, and fusion.37 Additional to these passive fusion methods, the Pasqualini group has reported an active method for levitation and fusion of magnetic labeled cell mass or spheroids by spatially controlling the magnetic field.38 However, these spheroid fusion methods rely on the random cell spheroid contact, and cannot precisely manipulate the orientation and spatial distribution of cell spheroids or organoids for the formation of controllable assembloids.

The recent advance of acoustofluidics39–41 may provide an alternative solution to achieve the controllable fusion of cell spheroids or organoids. This technology merges acoustics and microfluidics to manipulate suspended solid objects and liquids for basic and translational research in biomedical sciences.42–44 Superior to other technologies that employ gravity, magnetic, and mechanical forces, this technique can manipulate biological specimens from micro to macro-scale in a label-free, contact-free, and highly biocompatible manner.45–49 Efforts have been made on the development of acoustofluidics for the cell spheroid and organoid studies. For example, Chen and his colleagues have employed acoustic surface standing waves or Faraday waves for patenting and assembling large amounts of cell spheroids into different geometries.50, 51 Our group has developed a series of surface acoustic wave-based acoustofluidic devices for the fabrication of cell spheroids,52–55 as well as the trapping, patterning, and fusion of cell spheroids.56 Despite acoustofluidics provide a unique method for label-free, contact-free fusion or assembly of cell spheroids, it still lacks precise control over the orientation and spatial arrangement of cell spheroids. Recent attempts have been made on engineering the dynamic acoustic field to achieve rotational manipulation. For example, Marzo and his coworkers employed holographic acoustics57, 58 to form trapping vortex in the air to rotate droplets or particles.59 Moreover, acoustic streaming60, 61 has been used in the microfluidic environment for rotational manipulation. For example, the Huang group employed acoustically-oscillating bubbles and surface acoustic waves to develop a series of acoustic streaming-based devices for the rotational manipulation of single cells and Caenorhabditis elegans.62, 63 However, there are still tremendous needs to develop acoustofluidic technology for the fusion or assembly of cell spheroids and organoids with precise control over the orientation and spatial arrangement.

Herein, we developed a new acoustofluidic technique for the controllable fusion of organoids by regulating the dynamics acoustic field within a hexagonal acoustofluidic device. Our acoustofluidic method has several advantages: (1) This technology allows us to dexterously rotate, transport, and fuse one organoid with the other with the desired orientation in precision. (2) In contrast to the traditional organoid assembly method requiring meticulous pipetting and micromanipulation which could damage the organoids, the acoustic assembly process is gentle and contact-free. (3) The assembly process requires no special pre-labeling or medium, which can be broadly applied for many organoid based bioengineering models. As a proof-of-concept application, we used our novel method to establish a controllable fusion of organoids to study the development of neural circuitry such as the human mesocortical pathway.

2. Results and discussion

Modeling the human mesocortical pathway using acoustically-fused organoids.

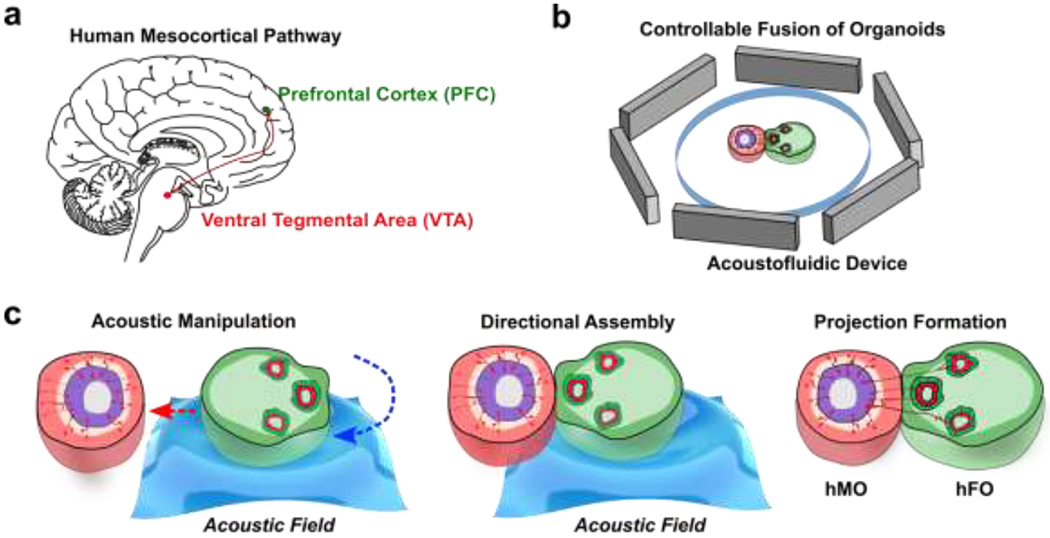

During human neural development, neurons from different brain regions project with specific morphogen and chemokine cues to form neural circuitries such as the cortico-striatal, the cortico-thalamic, and the mesocorticolimbic circuitry.64 Among these, dopaminergic pathways hold special significance, as they regulate key learning and reward-related behaviors. Moreover, disturbance of the dopaminergic pathway during early brain development can lead to neurological diseases such as schizophrenia, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism spectrum disorder (ASD).65 In the developing human midbrain, dopaminergic neurons (mDA) develop within the substantia nigra (SN) area and the ventral tegmental area (VTA). The mDA from the VTA, commonly showing OTX2+, CALB1+, TH+ phenotype, then projects towards the forebrain prefrontal cortex (PFC) to form the mesocortical pathway (Figure 1a).66 However, human assembloid models have not been employed to recapitulate the development of this important pathway. As a proof-of-concept application, we developed acoustofluidic devices (Figure 1b) and manipulation strategy for the controllable fusion of human forebrain organoids (hFOs) and human midbrain organoids (hMOs). The acoustically fused hFO-hMO assembloids is expected to model the human mesocortical pathway development, which consists of dopaminergic neuron projections from the midbrain ventral tegmentum (VTA) area to the forebrain prefrontal cortex (PFC) area.67 To model this projection, we generated hFOs and hMOs derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESC, WA01) and assembled them together to observe tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) neuron projection from hFO and hMO. Using an acoustofluidic device, we could rotate and transport the organoids to align the hFO neuroepithelial buds towards or away from hMO to observe differential neuron projection and maturation under various orientations (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. The controllable fusion of hMOs and hFOs to model the mesocortical pathway.

(a) Representation of VTA-PFC projection in a human brain. (b) Schematic of acoustofluidic device for the controllable fusion of organoids. (c) The acoustic fusion of an hMO and an hFO into an hMO-hFO assembloid with precision control over organoid arrangement and neuroepithelial bud location.

Fabrication of brain region-specific organoids.

To recapitulate human VTA-PFC projection in the mesocortical pathway, we adopted a brain region-specific organoids fabrication protocol (Table S1–3).68 We derived hFO by dual-SMAD inhibition followed by GSK3β inhibition, the hFO developed successfully with a well-defined ventricular/subventricular zone (VZ/SVZ) consists of PAX6+ neural progenitor cells and cortical plate (CP) consists of MAP2+ mature neurons (Figure S1). To mimic VTA development, we adopted a midbrain organoid protocol with initial treatment of dual-SMAD inhibition together with Shh/Fgf8 pathway agonist followed by GSK3β inhibition. We were able to generate human midbrain organoids (hMOs) with floor-plate progenitors and TH neurons. Upon closer examination, our hMOs showed preferential expression of VTA progenitor markers (OTX2) over substantia nigra (SN) progenitor markers (SOX6),69 as well as higher expression of VTA neuron marker (CALB1) over SN neuron marker (ALDHA1), validating its “VTA-like” phenotype (Figure S2).70 To note, OTX2 and SOX6 expression cannot exclusively distinguish midbrain neuron identity as both VTA and SN contain mixed cell types which can be further classified into 5-6 groups by single-cell RNA-seq.71–73 Thus, the heterogeneity within our hMO showing mixed expression OTX2+ and SOX6+ could be partially attributed to intrinsic heterogeneity within the developmental program. In addition to VTA cellular identity, we further confirmed our hMOs express mature mDA neuron markers including TH and NURR1 by qPCR, confirming successful neuron differentiation and maturation inside our hMOs (Figure S3).

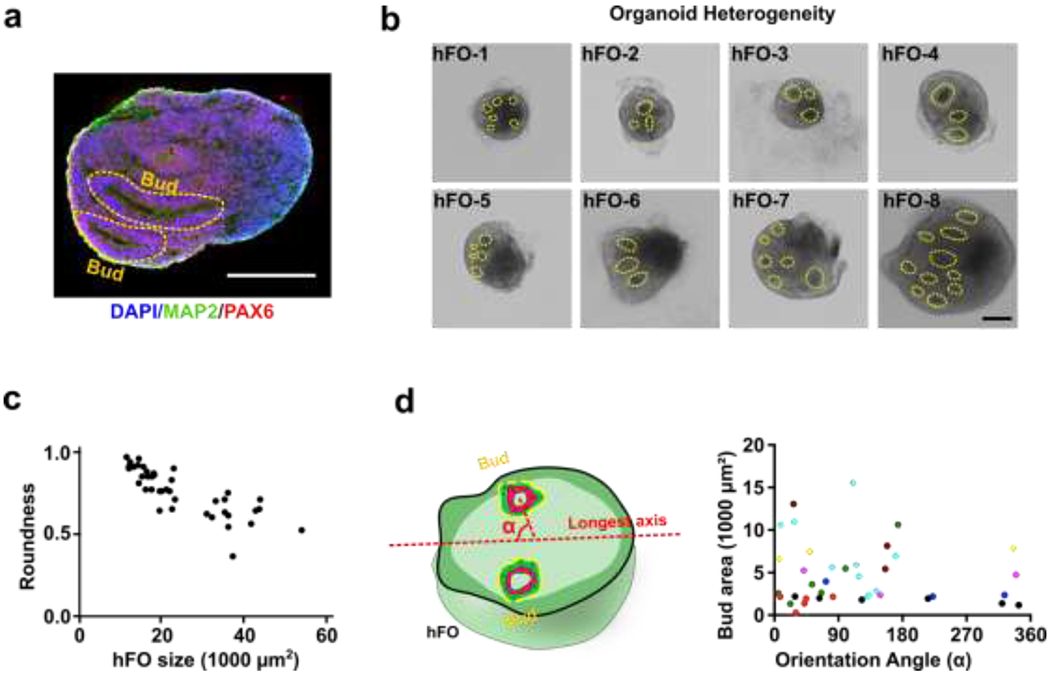

Characterization of heterogeneity in human forebrain organoids.

We then characterized the baseline heterogeneity of the hFO organoids in size, morphology, distribution of asymmetric features such as neuroepithelial buds (referred to as “bud” in following denotations). We found vast heterogeneity in these organoids (Figure 2a, and b). For example, we observed 18-day-old hFOs with highly variable sizes and shapes (size ranging from 11,543 ¼m2 to 54,508 ¼m2; roundness ranging from 0.37 to 0.98; n=40) (Figure 2c). Moreover, we also found the number, size, location, and orientation of neuroepithelial buds (indicated by yellow circles) vary dramatically in-between organoids. This indicated the uneven distribution of underlying VZ/SVZ regions within these organoids as they align with bud distribution. We analyzed these hFOs to quantify the variation of bud sizes and orientation (orientation angle α, 119.0 ± 101.2°; bud size, 4654 ± 3617 ¼m2; n=40) (Figure 2d). Given such heterogeneity, the uncontrolled fusion of heterogeneous hFOs and hMOs will likely introduce significant heterogeneity to the formation of hFO-hMO assembloids.

Figure 2. The heterogeneity of hFOs.

(a) The neuroepithelial bud presents the structure of the subventricular zone (neural progenitor marker PAX6, in red; neuron marker MAP2, green; cell nucleus DAPI, blue). (b) Eight hFOs generated from one bench have the random number and location of neuroepithelial buds (in yellow circle). (c) The size and shape heterogeneity of hFOs from the same batch (n=40). (d) Representative bud localization in forebrain organoids, indicated by size and orientation angle from the longest axis- α. Localization of each bud is indicated by the deviation angle α, which is the orientation angle between the longest axis of the organoid and the line linking the geometric center of the bud and the geometric center of the forebrain organoid. Buds from the same hFO are shown in the same color (n=8). Scale bar: 200 μm

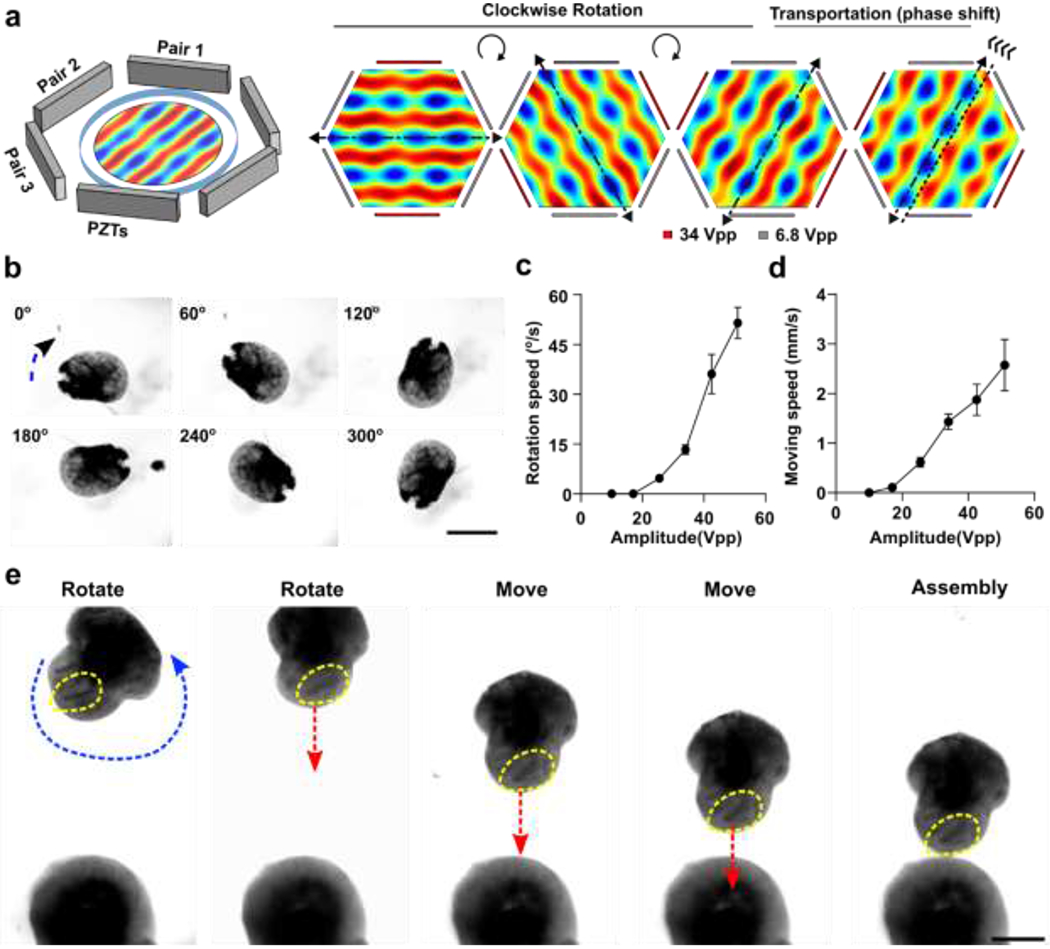

Acoustofluidic manipulation of organoids.

To interrogate whether the initial arrangement of buds affects hMO to hFO projection, we developed an acoustofluidic method to manipulate and fuse organoids with excellent control over the spatial arrangement of hFO and hMO. By regulating dynamic acoustic fields within a hexagonal acoustofluidic device, we can rotate, transport, and fuse one hFO with one hMO in a contact-free, label-free, and highly-biocompatible manner. The hexagonal acoustofluidic device consists of pairs of piezoelectric transducers (PZT, lead zirconate titanate), and an organoid chamber (Figure 3a, Figure S4). By independently tuning the phase and amplitude of input radio frequency (RF) signals, the generated dynamic pattern of acoustic fields can enable the rotational and transportational manipulation of single organoids. To predict and optimize human organoid handling, we simulated the acoustic fields generated within the hexagonal acoustofluidic device. By sequentially increasing the amplitude of RF signals applied to one selected PZT pair within the three pairs, the orientation of periodically-distributed pressure nodes (blue nodes) rotated accordingly in a clockwise direction (Figure 3a, Movie S1). By tuning the phase-angle between two PZT transducers with the selected pair, the position of periodically-distributed pressure nodes (blue nodes) moved along the PZT pair direction forward or backward accordingly (Figure 3a, Movie S2). Then, after trapping an hFO within pressure nodes in our hexagonal acoustofluidic device, we rotated the trapped organoid from 0° to 60°, 120°, 180°, 240°, and 300° (Figure 3b, Movie S3) by sequentially rotating the orientation of pressure node patterns. We further quantified the rotational speed of the trapped organoid by modulating the amplitudes of RF signals applied to the three PZT pairs (Pair1 = 6.8 Vpp, Pair2 = 6.8 Vpp, Pair3 = 10 ~ 40 Vpp). By increasing the amplitude of the PZT pair, the rotational speed of the trapped organoid increased accordingly (Figure 3c). Moreover, our method can achieve the on-demand rotation angle by controlling the time and amplitudes of the applied RF signals to the three PZT pairs. Similarly, by modulating the amplitude, phase-angle, and duration of RF signals applied to the three PZT pairs, the trapped organoid can be transported to the desired distance along the PZT pair direction with a moving speed ranging from 0 to 3 mm/s (Figure 3d). Thus, by combining the rational and transportational manipulation of organoids, we can trap, move, and/or rotate the selected organoid to the target location with the desired orientation within our organoid chamber.

Figure 3. Acoustic manipulation and assembly of organoids.

(a) Schematics of the acoustic device, and simulation of Gor’kov potential fields for the rotational and transportational manipulation of organoids. (b) Corresponding experimental results (optical microscopy images) were taken for the three amplitudes combinations. The organoid was trapped along 30, 90, 120, 180, 240, and 300º (to the vertical direction) respectively. (c) Experimental results showing the dependence of the rotational angular speeds on the input amplitudes. (d) Experimental results showing the dependence of the manipulation movement speed on the input amplitudes. (e) Demonstration of acoustic directional assembly of hFO and hMO. Scale bars, 500 μm

The controllable fusion of hFO and hMO.

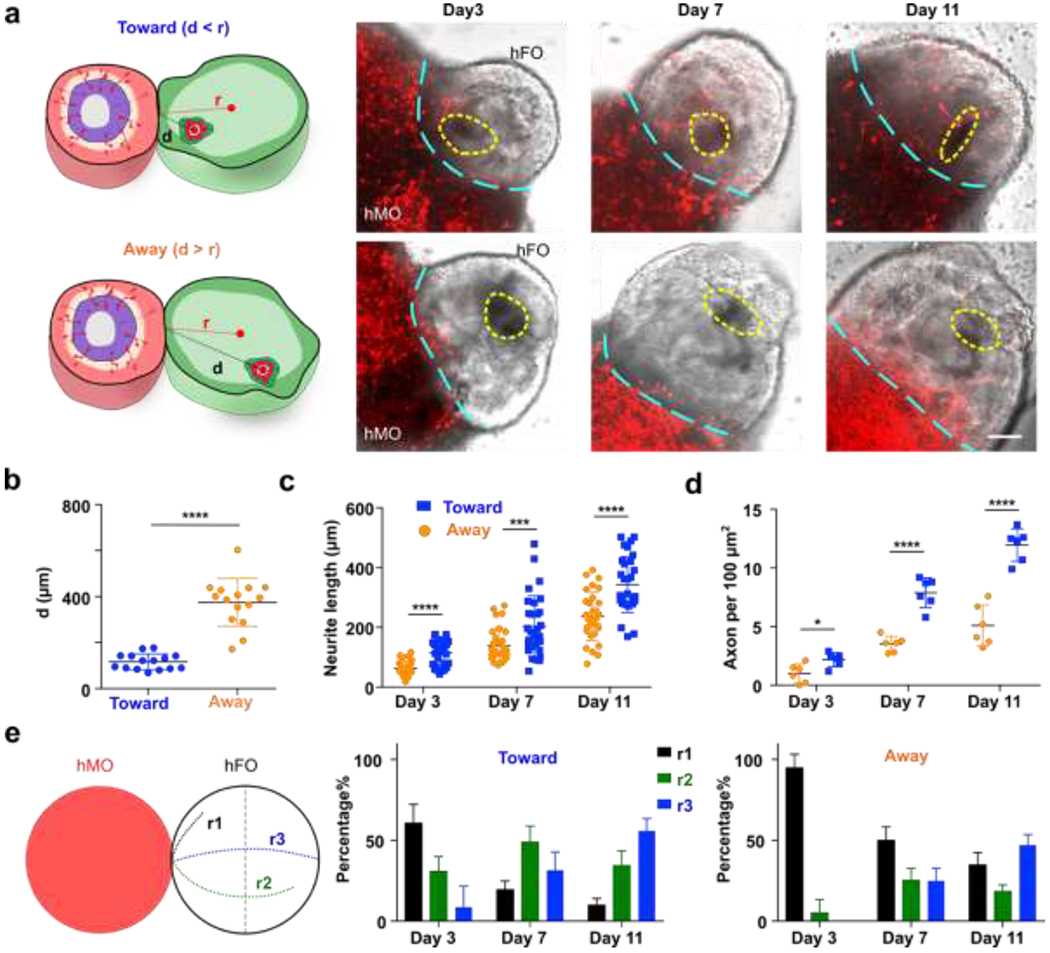

We further applied our acoustofluidic method for the directional fusion of hFOs and hMOs. To demonstrate orientation control during hFO-hMO fusion, we first rotated an hFO via amplitude modulation, the neuroepithelial bud (indicated by yellow dotted circles) within the hFO was rotated to face toward to the hMO. Then, the organoids were transported along the vertical direction step by step towards the immobilized hMO in the organoid chamber while maintaining the same relative orientation of the neuroepithelial bud. By further tuning the phase, the hFO finally contacted with the hMO with the desired orientation for neuroepithelial bud alignment (Figure 3e, Movie S4). Using this highly biocompatible method (Figure S5), we then interrogated the effect of the initial orientation of hFO buds on organoid fusion. We first defined the distance between the hMO-hFO contact point and the geometric center of the hFO “bud” and as “d”, and its distance from the geometric center of the whole hFO as “r”. We then manipulated the fusion of hFOs and hMOs to generate a “Toward group” with all hFO buds rotated towards hMO (d < r, short d) and an “Away group” with all hFO buds rotated away from hMO (d > r, long d, Figure 4a, Figure S6). In the cases where hFO buds were more evenly distributed and could not be rotated into one side of the midline, we excluded those hFOs. This generated distinct hFO bud-to-hMO distances between the two groups (Toward group, 121.3 μm; Away group, 391.5 μm; p < 0.001, Figure 4b).

Figure 4. Fusion dynamics of controllable hMO-hFO assembloids.

(a) hFO was rotated to have all bud toward (d<r) or away (d>r) from hMO. hMO neuron projections labeled with mCherry expression (red) were imaged and recorded under a fluorescent microscope, buds are marked with dotted yellow circles, and the interface between hMO and hFO is marked with cyan dotted lines. (b) Comparison of hFO bud distance from hMO in the toward and away group. (n=15, p<0.001). (c) Distribution of projection neurite length over time (n=30, p<0.001) (d) Average axon density and its dynamic change in the toward and away groups over time (n=6, p<0.001). (e) Definition of range index in hMO-hFO projection. hMO neurite projections that did not reach midline of hFO are scored as r1; hMO neurite projections past midline of FO but did not reach the very end of hFO are scored as r2; hMO neurite projections that reached the very end of hFO are scored as r3. Distribution of range index and the dynamic change over time was different in the toward and away group (n=6). Scale bar: 100 μm

Projection dynamics characterization of controllable fused hFO-hMO assembloids.

We then characterized the neuron projection dynamics right after the acoustic fusion of hMOs and hFOs in both the “Toward” and “Away” groups. During the neuron projection formation processes, we characterized the projection neurite length, density, and range index in both the Toward and Away groups. To visualize the hMO neurons, we transfected hMOs with mCherry to track their projecting axons towards hFOs in the acoustically-fused organoids. We validated the mCherry transfection successfully labeled >90% of the midbrain TH+ neurons by immunofluorescence (Figure S7a). We analyzed projection mCherry+ neuron length, density and range index using Image J and compared the hMO-hFO projections in the Toward and Away groups, following a reported method.10 We found that the Toward group has significantly longer neurites than the Away group (e.g., Toward group, 343.3 ± 93.8 μm; Away group, 236.5 ± 81.3 μm; p < 0.001, n = 30, at day 11, Figure 4c). In addition, the Toward group also has significantly higher neurite density than the Away group (e.g., Toward group, 11.9 ± 1.4 per 100 μm2; Away group, 5.1 ± 1.8 per 100 μm2; p < 0.001, n = 6, at day 11, Figure 4d). Furthermore, we quantified the range index74 as following: projecting midbrain neurons that did not cross the midline of hFOs were scored with a range index of r1; neurons crossing midline but did not reach the furthest end of hFOs were scored as r2; neurons projected to the very end of hFOs were scored as r3. We observed that within the Toward group, 31.5 ± 11.3% neurons projected to the very end of hFOs (r3) at day 7, and 55.8% ± 7.7% neurons scored r3 on day 11. In contrast, in the Away group only 25.0% ± 7.1% reached r3 by day 7 and 47.0% ± 6.6% at day 11 (Figure 4e). To conclude, we observed that the Toward group has a greater length, higher density, and faster formation of projection neurites than the Away group, indicating the initial orientation contributes significantly to the fusion dynamics of hFO and hMO. This is likely due to the initial proximity as well as higher concentrations of TH neuron axonal guidance molecules.75

Functionality study of controllable fused hFO-hMO assembloids.

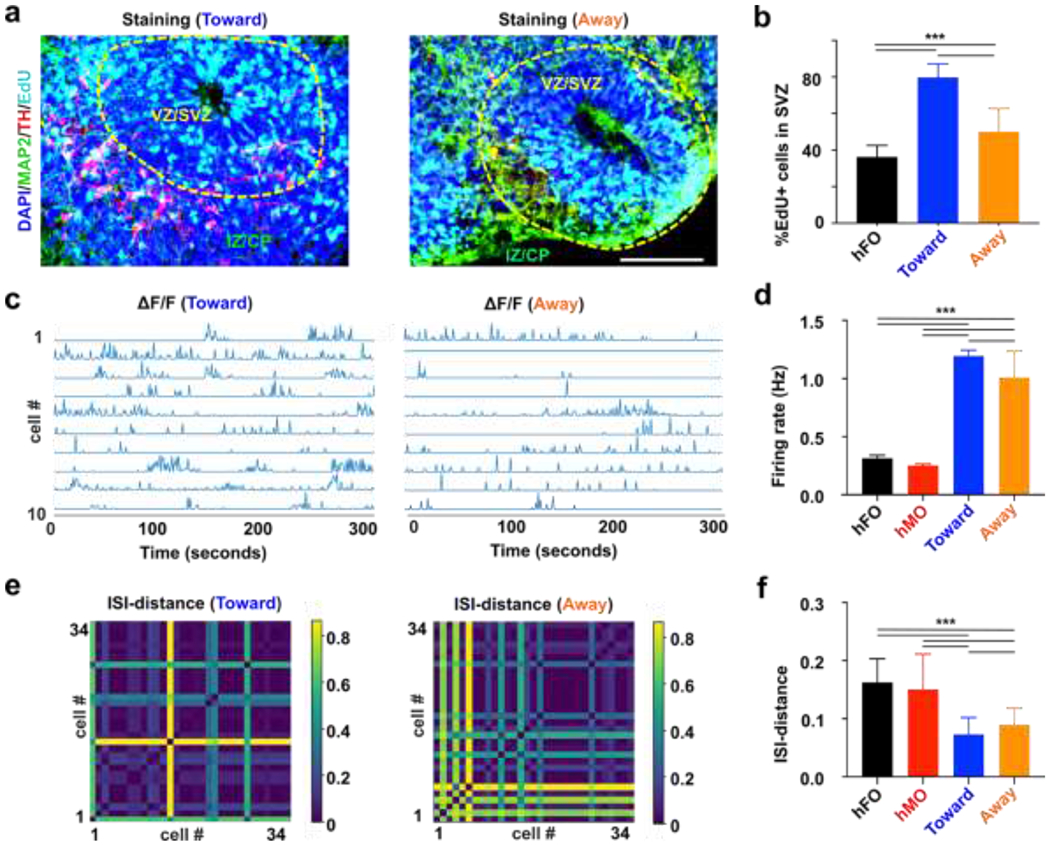

We further characterized how the differential initial orientation affects the functionality of hFO-hMO assembloids. The tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) neurons are a key subtype of midbrain dopamine (mDA) neurons, which is born in the midbrain and then projecting to the striatum and prefrontal cortex in a developing human brain.76 Additionally, it was reported that TH neuron projections outside VZ/SVZ promote the proliferation of neural progenitor cells inside VZ/SVZ both prenatally and postnatally.77 Thus, we validated the establishment of midbrain-to-forebrain projection in our hFO-hMO assembloids by staining the projection of TH neurons. We confirmed the projection TH neurons are hMO derived by co-staining to label TH and mCherry, as mCherry viral labeling was only done to hMO. We found that the TH staining overlaps with mCherry staining (Figure S7b), confirming the origin of TH neurons. Additionally, we did not identify any TH positive neurons in the hFO alone, consistent with our qRT-PCR data, excluding the possibility of hFO origin of TH neurons (Figure S7c). We then characterized TH neuron projection in our hFO-hMO assembloid model. We found that TH neurons in our hFO-hMO assembloids could preferably project from hMO to the thin layer outside of VZ/SVZ of hFOs (Figure 5a), recapitulating the pattern seen in vivo in rodents and human.78 We then analyzed the proliferation of neural progenitor cells (NPC) (EdU+) in hFOs. We found that NPCs proliferate faster in hFO-hMO assembloids as compared with hFO alone. More importantly, the Toward group see an even higher proliferation rate as compared with the Away group (hFO alone group, 36.2 ± 6.4%; Toward group, 79.8 ± 7.4%; Away group 50.0 ± 12.8%; p < 0.005, n = 6, Figure 5b). This demonstrated the importance of controlling initial bud orientation and distribution during the organoid assembly.

Figure 5. Projection formation in controllable hMO-hFO assembloids.

(a) Representative immunofluorescence image of hMO-hFO assembloid in the toward group (Cell nucleus-DAPI-blue; Dopamine neurons-TH-red; Forebrain neurons-MAP2-green; proliferative cells-EdU-cyan). (b) Percentage of newly proliferated cells (EdU+) cells in hFO, hMO-hFO assembloid in the toward and away group (p<0.005, n=6). (c) Representative calcium traces of ten active neurons extracted from movies of toward and away group. (d) Average firing rate of excitatory neurons in the hFO, hMO and assembloids in the toward and away groups. (e) ISI-distance matrix of 34 extracted calcium traces of excitatory neurons in the assembloids in the toward and away groups. (f) Average ISI-distance of excitatory neurons in hFO, hMO and the toward and away groups of hMO-hFO assembloids. Scale bar: 100 μm

Additionally, we also examined the electrophysiology of acoustically-fused hMO-hFO assembloids. In vivo, dopaminergic inputs from midbrain VTA was shown to modulate firing patterns and local field potential (LFP) oscillatory activity in PFC.79 Activation of dopamine receptor-D1 positive PFC neurons also activates its burst firing, as indicated by higher firing rates and lower inter-spike intervals (ISIs).80 To examine whether our hMO-hFO could recapitulate key in vivo electrophysiological features, we recorded and analyzed the spontaneous firing in hFOs and acoustically fused hFO-hMO assembloids by calcium imaging (Movie S5). Briefly, hMO-hFO assembloids were transfected with adenovirus expressing GCaMP6s calcium reporter under either a CAMKII promoter (for hFO and hFO-hMO assembloids), limiting the calcium reporter expression in excitatory neurons or under a Synapsin promoter to label general active neurons for hMO calcium imaging. We analyzed the spontaneous firing rate (Figure 5c) and ISI distances (Figure 5e) of excitatory neurons in 1-month-old hFO-hMO assembloids (Toward and Away groups), and hFOs (5 per group). They had significantly different spontaneous firing as hFO-hMO assembloids showed higher firing rate, especially in the Toward group (hFOs alone, 0.31 ± 0.03 Hz, # of neurons = 63; Toward group, 1.19 ± 0.05 Hz, # of neurons = 312; Away group, 1.01 ± 0.23 Hz, # of neurons = 287; p < 0.005, Figure 5d). Moreover, shorter ISI distances indicating higher synchrony were observed in assembloids, especially in the Toward group (hFOs alone, 0.16 ± 0.04, # of neurons = 63; Toward group, 0.073 ± 0.029, # of neurons = 312; Away group, 0.089 ± 0.029, # of neurons = 287; p < 0.005, Figure 5f). These pieces of evidence together demonstrate that initial contact orientation of bud distribution is an important factor in organoid fusion dynamics.

3. Conclusions

In summary, we reported an acoustofluidic method to controllably rotate and assemble brain-region specific organoids. We demonstrated that the rotation and directional assembly of hFOs and hMOs could facilitate and manipulate the neuron projection and function in the hFO-hMO assembloids for modeling midbrain to forebrain projections in the mesocortical pathway. Taking the unique advantage of acoustics and microfluidics, this technique allows high-precision organoids or 3D in vitro cultures in a contact-free, label-free, highly compatible fashion. Moreover, this acoustofluidic technology is simple, versatile, and effective for engineering the fusion of organoids, which could be applicable for various organoids and 3D cultures with variable morphological features. We believe this tool can be broadly applied for human organoid-based organ developmental research, disease modeling, drug screening, and translational medicine.

4. Experimental

Device fabrication and operation.

The acoustic assembly device consists of six PZTs) embedded into a laser-cut substrate and a cell culture dish. A 9 mm thick acrylic sheet was laser cut into the substrate of the device with an inner chamber of 40mm x 40mm and four small outer chambers for four embedded PZTs. The PZTs (20 × 10 × 3mm, 1MHz resonant frequency) were affixed to the outer chambers with epoxy, and a 3 mm thick acrylic sheet was glued to the substrate bottom to allow the chamber to contain DI water. The opposite two PZTs were wired together to a pair, and two pairs of PZTs were driven independently by two unsynchronized 1MHz RF signals. The RF signals were generated by a function generator (TGP3152, Aim TTi) and amplified by power amplifiers (LZY-22+, Minicircuit) to drive the acoustic assembly device. A cell culture dish (35mm, Greiner Bio) was employed to contain cell solutions and avoid contamination during the acoustic assembly process, the water-filled acrylic chamber was used to guide acoustic wave into the petri dish. In the acoustic assembly experiment, brain region-specific organoids were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplied with 5% Gel-MA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% Irgacure D-2959 (Sigma-Aldrich) were introduced into the acoustic pattern chamber. RF signals (1MHz, 17Vpp) were applied to the PZTs to generate acoustic trapping patterns. After acoustic patterning to ensure the correct positioning of the organoids, the solution was crosslinked for 30 seconds using ultraviolet light (365 nm, 6 mW cm−2). The crosslinked solution containing assembloids was transferred to a glass-bottom 24-well plate (MatTek Corporation) for confocal imaging and cultured in the corresponding culture medium.

Simulation of acoustic fields.

The numerical simulation of the acoustic field in our acoustofluidic manipulation device was conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics 5.2a. To save the computational cost, we simplified the 3D realistic problem to a 2D computational problem. In Figure S4b, our numerical model considered the interaction of propagating acoustic waves in the hexagon fluidic chamber, and the three pairs of PZTs were considered as plane acoustic waves radiation boundaries located at the six edges of the hexagon chamber. The 2D model with predefined plane waves radiation boundaries conditions was solved using the frequency domain of predefined pressure acoustics solver in the COMSOL. The corresponding simulation of rotation and 2D manipulation was conducted via modification of amplitudes and phase shift as described in the main text (Figure S4c).

Fabrication of brain-region specific organoids.

Human embryonic stem cell line WA01 was purchased from WiCell. Cells were maintained on Matrigel (Corning) coated 6 well plates and cultured in mTeSR plus medium (Stemcell Technologies) with a medium change every other day using a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. WA01 cells were passaged once every week using ReLeSR (Stemcell Technologies). Brain region-specific organoids were fabricated using an adapted protocol.30 Briefly, 9,000 WA01 cells were suspended in each well of a spheroid formation plate (Corning) to form embryonic bodies (EBs). EBs were then exposed to the forebrain, midbrain brain organoid development strategy respectively following medium composition. The detailed medium composition can be found in Supplementary Table S2 and S3. Forebrain organoids were embedded in 33% Matrigel (Corning) on day 7, with Matrigel removal on day 14. Midbrain organoids were cultured in suspension and subject to orbital shaker rotation on Day 14. To rotate organoids in an orbital shaker, 6-10 organoids were set in 1 well of a 6-well plate on a standard orbital shaker (Thermo Fisher) and the shaker was set at a speed of 80 rpm.

Fluorescence protein labeling of midbrain neuron projections:

To visualize midbrain neuron projection from hMO to hFO, 1-week-old hMOs were incubated with a titer > 1X109 vg/mL AAV2-hSyn-mCherry for 24 hours to label hMO neurons. hMOs were allowed 1 week or longer to express mCherry before assembled with hFO to study neuron projection.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Brain region-specific organoids and assembloids were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. The fixed organoids were then washed twice in 1X phosphate-buffered saline (1XPBS) (Gibco) and transferred to 30% sucrose (w/v) to cryoprotect at 4°C overnight. After cryoprotection, the organoids were then embedded in O.C.T. compound (Fisher healthcare) and froze at −80°C. The frozen blocks were then be sectioned into 20μm thickness slices and adhered to charged glass slides (Fisher Scientific). The slices were then blocked with a blocking buffer made with 5% normal goat serum (Abcam) and 0.3 % Triton™ X-100 (Sigma) in 1XPBS (Gibco) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by primary antibody incubation at 4°C overnight. Detailed antibody information can be found in Supplementary Table S1. The slides were then washed with 1XPBS 3 times and incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:500 for 1 hour. The stained slides were washed with 1XPBS 3 times and counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). To stain proliferative cells with EdU, organoids were labeled with EdU-Alexa 647cell proliferation kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, forebrain organoids or assembloids were incubated with 10 μM of EdU for 12 hours. The EdU labeled organoids were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and cryoprotected 30% sucrose (w/v) overnight. Organoids were then embedded in O.C.T. compound (Fisher healthcare) and cryo-sectioned into 20μm thickness slices. Sectioned slices were first subjected Click-iT reaction cocktail to label the EdU+ cells with Alexa 647. The labeled slices were then subject to primary and secondary antibody staining as described above.

qRT-PCR.

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed by extracting total RNA from day 1 EB (baseline control) or day 35 organoids (n=3) using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen). The extracted RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (applied biosystems). The cDNA was then analyzed by qPCR using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (applied biosystems). Primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table S1. The fold change (FC) is calculated by normalizing gene expression against housekeeping gene GAPDH and then compare them with gene expression level in day 1 EB.

Ca2+ imaging and data processing.

To image hFO excitatory neuron firing, hFOs or hFO-hMO assembloids were transfected with pAAV.CamKII.GCaMP6s.WPRE.SV40. hMOs were transfected with pAAV.Syn.GCaMP6s.WPRE.SV40. After transfection at a titer > 1X109 vg/mL for 24 hours, the assembloid were allowed 3 days to fully express the GCaMP6s reporter. The assembloid was then imaged under an Olympus OSR spinning disk microscope at a frame rate of 10 Hz for 5 minutes. The data processing was conducted using a custom processing package based on Python. The processing pipeline included: (i) Motion correction, (ii) source extraction, (iii) activity deconvolution, and (iv) following analysis. The first three steps were performed using CaImAn software to get the deconvoluted Ca2+ activity traces. We run CaImAn with default parameters except for some parameters adjusted to fit our records: imaging frame rate in frames per second, half-size of the patches in pixels, overlap between patches in pixels, the number of components per patch, expected half-size of neurons in pixels. The following analysis was performed with extracted Ca2+ activity traces. The ISI-distance matrixes were calculated using PySpike.

Statistical analysis.

The statistics to compare the difference between the two groups were conducted using the students’ t-test using GraphPad Prism 7. Statistical significance was denoted as following: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005. ****p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

6. Acknowledgments

Z.A. and H.C. contributed equally to this work. F.G. acknowledges the departmental start-up funds of Indiana University Bloomington, and funding support from the National Institute of Health (1R03EB030331). H.W. acknowledges funding support from the National Institute of Health (1K01MH117490). The authors thank the Indiana University Imaging Center (NIH1S10OD024988) and Nanoscale Characterization Facility for use of their instruments.

Footnotes

5. Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lancaster MA and Knoblich JA, Science, 2014, 345, 1247125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo C, Lancaster MA, Castanon R, Nery JR, Knoblich JA and Ecker JR, Cell Rep, 2016, 17, 3369–3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Lullo E and Kriegstein AR, Nat Rev Neurosci, 2017, 18, 573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schutgens F and Clevers H, Annu Rev Pathol, 2020, 15, 211–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasai Y, Eiraku M and Suga H, Development, 2012, 139, 4111–4121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clevers H, Cell, 2016, 165, 1586–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paşca SP, Science, 2019, 363, 126–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagley JA, Reumann D, Bian S, Lévi-Strauss J and Knoblich JA, Nat Methods, 2017, 14, 743–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birey F, Andersen J, Makinson CD, Islam S, Wei W, Huber N, Fan HC, Metzler KRC, Panagiotakos G, Thom N, O’Rourke NA, Steinmetz LM, Bernstein JA, Hallmayer J, Huguenard JR and Pasca SP, Nature, 2017, 545, 54–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, Cakir B, Patterson B, Kim KY, Sun P, Kang YJ, Zhong M, Liu X, Patra P, Lee SH, Weissman SM and Park IH, Cell stem cell, 2019, 24, 487–497.e487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, Patterson B, Kang YJ, Govindaiah G, Roselaar N, Cakir B, Kim KY, Lombroso AP, Hwang SM, Zhong M, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Naegele JR, Lee SH, Weissman SM and Park IH, Cell Stem Cell, 2017, 21, 383–398.e387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marton RM and Pașca SP, Trends in Cell Biology, 2020, 30, 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linkous A, Balamatsias D, Snuderl M, Edwards L, Miyaguchi K, Milner T, Reich B, Cohen-Gould L, Storaska A, Nakayama Y, Schenkein E, Singhania R, Cirigliano S, Magdeldin T, Lin Y, Nanjangud G, Chadalavada K, Pisapia D, Liston C and Fine HA, Cell reports, 2019, 26, 3203–3211.e3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogawa J, Pao GM, Shokhirev MN and Verma IM, Cell Reports, 2018, 23, 1220–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marx V, Nature Methods, 2020, 17, 961–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon SJ, Elahi LS, Pasca AM, Marton RM, Gordon A, Revah O, Miura Y, Walczak EM, Holdgate GM, Fan HC, Huguenard JR, Geschwind DH and Pasca SP, Nat Methods, 2019, 16, 75–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuster B, Junkin M, Kashaf SS, Romero-Calvo I, Kirby K, Matthews J, Weber CR, Rzhetsky A, White KP and Tay S, Nature Communications, 2020, 11, 5271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velasco V, Shariati SA and Esfandyarpour R, Microsystems & Nanoengineering, 2020, 6, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tissue Engineering Part A, 2020, 26, 656–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasendra M, Tovaglieri A, Sontheimer-Phelps A, Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, Bein A, Chalkiadaki A, Scholl W, Zhang C, Rickner H, Richmond CA, Li H, Breault DT and Ingber DE, Scientific Reports, 2018, 8, 2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huh D, Matthews BD, Mammoto A, Montoya-Zavala M, Hsin HY and Ingber DE, Science, 2010, 328, 1662–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lancaster MA, Corsini NS, Wolfinger S, Gustafson EH, Phillips AW, Burkard TR, Otani T, Livesey FJ and Knoblich JA, Nature Biotechnology, 2017, 35, 659–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandenberg N, Hoehnel S, Kuttler F, Homicsko K, Ceroni C, Ringel T, Gjorevski N, Schwank G, Coukos G, Turcatti G and Lutolf MP, Nat Biomed Eng, 2020, DOI: 10.1038/s41551-020-0565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorrentino G, Rezakhani S, Yildiz E, Nuciforo S, Heim MH, Lutolf MP and Schoonjans K, Nature Communications, 2020, 11, 3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broguiere N, Lüchtefeld I, Trachsel L, Mazunin D, Rizzo R, Bode JW, Lutolf MP and Zenobi-Wong M, Advanced Materials, 2020, 32, 1908299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nikolaev M, Mitrofanova O, Broguiere N, Geraldo S, Dutta D, Tabata Y, Elci B, Brandenberg N, Kolotuev I, Gjorevski N, Clevers H and Lutolf MP, Nature, 2020, 585, 574–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Wang Y, Wang H, Zhao M, Tao T, Zhang X and Qin J, Advanced Science, 2020, 7, 1903739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Wang L, Guo Y, Zhu Y and Qin J, RSC Advances, 2018, 8, 1677–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Y, Wang L, Yu H, Yin F, Wang Y, Liu H, Jiang L and Qin J, Lab on a Chip, 2017, 17, 2941–2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian X, Jacob F, Song MM, Nguyen HN, Song H and Ming G-I, Nature Protocols, 2018, 13, 565–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ao Z, Cai H, Havert DJ, Wu Z, Gong Z, Beggs JM, Mackie K and Guo F, Analytical Chemistry, 2020, 92, 4630–4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadoshima T, Sakaguchi H, Nakano T, Soen M, Ando S, Eiraku M and Sasai Y, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2013, 110, 20284–20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lennington JB, Pope S, Goodheart AE, Drozdowicz L, Daniels SB, Salamone JD and Conover JC, The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2011, 31, 13078–13087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prestoz L, Jaber M and Gaillard A, Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 2012, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim TY, Kofron CM, King ME, Markes AR, Okundaye AO, Qu ZL, Mende U and Choi BR, Plos One, 2018, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Susienka MJ, Wilks BT and Morgan JR, Biofabrication, 2016, 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomasi RFX, Sart S, Champetier T and Baroud CN, Cell Rep, 2020, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Souza GR, Molina JR, Raphael RM, Ozawa MG, Stark DJ, Levin CS, Bronk LF, Ananta JS, Mandelin J, Georgescu MM, Bankson JA, Gelovani JG, Killian TC, Arap W and Pasqualini R, Nat Nanotechnol, 2010, 5, 291–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friend J and Yeo LY, Reviews of Modern Physics, 2011, 83, 647–704. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozcelik A, Rufo J, Guo F, Gu Y, Li P, Lata J and Huang TJ, Nat Methods, 2018, 15, 1021–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ding XY, Li P, Lin SCS, Stratton ZS, Nama N, Guo F, Slotcavage D, Mao XL, Shi JJ, Costanzo F and Huang TJ, Lab on a Chip, 2013, 13, 3626–3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo F, Xie Y, Li S, Lata J, Ren L, Mao Z, Ren B, Wu M, Ozcelik A and Huang TJ, Lab on a Chip, 2015, 15, 4517–4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo F, Zhou W, Li P, Mao Z, Yennawar NH, French JB and Huang TJ, Small, 2015, 11, 2733–2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo F, Li P, French JB, Mao Z, Zhao H, Li S, Nama N, Fick JR, Benkovic SJ and Huang TJ, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112, 43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo F, Li P, French JB, Mao Z, Zhao H, Li S, Nama N, Fick JR, Benkovic SJ and Huang TJ, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2015, 112, 43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo F, Mao Z, Chen Y, Xie Z, Lata JP, Li P, Ren L, Liu J, Yang J, Dao M, Suresh S and Huang TJ, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2016, 113, 1522–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li F, Cai F, Zhang L, Liu Z, Li F, Meng L, Wu J, Li J, Zhang X and Zheng H, Physical Review Applied, 2020, 13, 044077. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo F, Mao Z, Chen Y, Xie Z, Lata JP, Li P, Ren L, Liu J, Yang J, Dao M, Suresh S and Huang TJ, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016, 113, 1522–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lata JP, Guo F, Guo J, Huang PH, Yang J and Huang TJ, Adv Mater, 2016, 28, 8632–8638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen P, Güven S, Usta OB, Yarmush ML and Demirci U, Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2015, 4, 1937–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen P, Luo ZY, Guven S, Tasoglu S, Ganesan AV, Weng A and Demirci U, Adv Mater, 2014, 26, 5936–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai H, Ao Z, Hu L, Moon Y, Wu Z, Lu H-C, Kim J and Guo F, Analyst, 2020, 145, 6243–6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen B, Wu Y, Ao Z, Cai H, Nunez A, Liu Y, Foley J, Nephew K, Lu X and Guo F, Lab on a Chip, 2019, 19, 1755–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu Y, Ao Z, Bin C, Muhsen M, Bondesson M, Lu X and Guo F, Nanotechnology, 2018, 29, 504006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen K, Wu M, Guo F, Li P, Chan CY, Mao Z, Li S, Ren L, Zhang R and Huang TJ, Lab on a Chip, 2016, 16, 2636–2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cai H, Wu Z, Ao Z, Nunez A, Chen B, Jiang L, Bondesson M and Guo F, Biofabrication, 2020, 12, 035025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Melde K, Mark AG, Qiu T and Fischer P, Nature, 2016, 537, 518–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marzo A and Drinkwater BW, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2019, 116, 84–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marzo A, Seah SA, Drinkwater BW, Sahoo DR, Long B and Subramanian S, Nat Commun, 2015, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin Y, Gao C, Gao Y, Wu MR, Yazdi AA and Xu J, Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical, 2019, 287, 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cai HW, Ao Z, Wu ZH, Nunez A, Jiang L, Carpenter RL, Nephew KP and Guo F, Analytical Chemistry, 2020, 92, 2283–2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang JX, Yang SJ, Chen CY, Hartman JH, Huang PH, Wang L, Tian ZH, Zhang PR, Faulkenberry D, Meyer JN and Huang OJ, Lab on a Chip, 2019, 19, 984–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ahmed D, Ozcelik A, Bojanala N, Nama N, Upadhyay A, Chen YC, Hanna-Rose W and Huang TJ, Nat Commun, 2016, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tau GZ and Peterson BS, Neuropsychopharmacology, 2010, 35, 147–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ayano G, J Ment Disord Treat, 2016, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- 66.La Manno G, Gyllborg D, Codeluppi S, Nishimura K, Salto C, Zeisel A, Borm LE, Stott SR, Toledo EM and Villaescusa JC, Cell, 2016, 167, 566–580. e519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nestler EJ, Nature neuroscience, 2005, 8, 1445–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qian X, Jacob F, Song MM, Nguyen HN, Song H and Ming GL, Nat Protoc, 2018, 13, 565–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Panman L, Papathanou M, Laguna A, Oosterveen T, Volakakis N, Acampora D, Kurtsdotter I, Yoshitake T, Kehr J, Joodmardi E, Muhr J, Simeone A, Ericson J and Perlmann T, Cell Reports, 2014, 8, 1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poulin J-F, Gaertner Z, Moreno-Ramos OA and Awatramani R, Trends in Neurosciences, 2020, 43, 155–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hook PW, McClymont SA, Cannon GH, Law WD, Morton AJ, Goff LA and McCallion AS, The American Journal of Human Genetics, 2018, 102, 427–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poulin J-F, Zou J, Drouin-Ouellet J, Youn K, Kim A, Cicchetti F and Awatramani RB, Cell Reports, 2014, 9, 930–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tiklová K, Björklund ÅK, Lahti L, Fiorenzano A, Nolbrant S, Gillberg L, Volakakis N, Yokota C, Hilscher MM, Hauling T, Holmström F, Joodmardi E, Nilsson M, Parmar M and Perlmann T, Nature Communications, 2019, 10, 581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xiang Y, Tanaka Y, Cakir B, Patterson B, Kim K-Y, Sun P, Kang Y-J, Zhong M, Liu X, Patra P, Lee S-H, Weissman SM and Park I-H, Cell stem cell, 2019, 24, 487–497.e487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brignani S and Pasterkamp RJ, Front Neuroanat, 2017, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Van den Heuvel DM and Pasterkamp RJ, Prog Neurobiol, 2008, 85, 75–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lao CL, Lu C-S and Chen J-C, Glia, 2013, 61, 475–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhong S, Zhang S, Fan X, Wu Q, Yan L, Dong J, Zhang H, Li L, Sun L, Pan N, Xu X, Tang F, Zhang J, Qiao J and Wang X, Nature, 2018, 555, 524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lohani S, Martig AK, Deisseroth K, Witten IB and Moghaddam B, Cell Rep, 2019, 27, 99–114.e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seong HJ and Carter AG, The Journal of Neuroscience, 2012, 32, 10516–10521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.