Abstract

Myo-inositol is a six-carbon sugar that is essential for the growth of mammalian cells and must be obtained through either extracellular uptake or de novo biosynthesis. The physiological importance of myo-inositol stems from its incorporation into phosphoinositides and inositol phosphates, which serve a variety of signaling, regulatory, and structural roles in cells. To study myo-inositol metabolism and function, it is essential to have a reliable method for assaying myo-inositol levels. However, current approaches to assay myo-inositol levels are time-consuming, expensive, and often unreliable. This article describes a simple new myo-inositol bioassay that utilizes an auxotrophic strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to measure myo-inositol concentration in solutions. The accuracy of this method was confirmed by comparing assay values to those obtained by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). It is easy to perform, inexpensive, does not require sophisticated equipment, and is specific for myo-inositol.

Keywords: Myo-inositol, bioassay, yeast

Introduction

Myo-inositol is a six-carbon cyclitol that is required for the growth and viability of eukaryotic cells (1–4). To remain viable, cells must obtain myo-inositol through either 1) transporter-mediated uptake of exogenous inositol or 2) de novo biosynthesis from glucose-6-phosphate (5). Myo-inositol synthesis and metabolism are conserved from yeast to humans. The first and rate-limiting step of myo-inositol synthesis is the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to inositol-3-phosphate (I3P) by the enzyme myo-inositol-3 phosphate synthase (MIPS) (6). I3P is dephosphorylated by inositol monophosphatase to myo-inositol. Phosphatidylinositol synthase catalyzes the interaction of myo-inositol and cytidine diphosphate diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) to generate phosphatidylinositol (PI) (6). Sequential phosphorylation of the inositol ring of PI produces diverse species of phosphoinositides, including phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), in the plasma membrane (6). PIP2 is hydrolyzed via phospholipase C (PLC) to generate the signaling molecules myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) (7). IP3 binds to IP3 receptors in the ER membrane, which induces conformational changes in the receptors and calcium release into the cytosol (8). The released calcium functions as a cofactor for several enzymes that regulate cell metabolism and proliferation (9).

Myo-inositol metabolism is connected to many aspects of cell function. Therefore, it is not surprising that myo-inositol imbalance is associated with several human diseases, including epilepsy, bipolar disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, and polycystic ovarian syndrome (10–12). The cyclitol is especially important for brain function, where the concentration can reach levels 20 times higher than in the blood (5). Myo-inositol is incorporated into phosphoinositides that are critical for many cellular functions, including intracellular vesicular transport of lipids and proteins, endo- and exocytosis of signaling ligands, regulation of the cytoskeleton, modulation of ion channels, and maintaining the structural integrity of membranes (5,13–15). Furthermore, specific proteins that function as hydrolytic enzymes or in cell-cell adhesion require phosphatidylinositol to remain anchored to cell membranes (16). Inositol phosphates are also derivatives of inositol and function as second messengers in cell signaling, energy metabolism, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional regulation (5,17,18). In yeast cells, myo-inositol supplementation alters the expression of hundreds of genes (19). Thus, the importance of studying the regulation of myo-inositol biosynthesis is emerging as an important frontier in biology research. In accordance with its importance for supporting cell growth, myo-inositol is included as a component of most commercially available mammalian cell culture media formulations and is naturally present in fetal bovine serum (F.B.S.) (2). Clearly, a reliable assay of inositol concentration is essential for studying inositol function.

The most widely used methods currently available for assaying myo-inositol levels include various biochemical assays, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Biochemical assays can be used in-house by most labs, data can be generated relatively quickly, and there is little constraint on how many samples can be run at a given time. However, many biochemical assay readouts rely on the enzymatic conversion of substrate to produce a fluorescent signal, which often results in noisy data that are susceptible to non-specific enzyme activity (20–22). LC-MS offers the benefit of being a direct measurement of myo-inositol. Experts typically perform the technique in MS core facilities, thus reducing the likelihood of technical error. However, many cores do not include myo-inositol in the standard list of metabolites assayed, thus requiring time-consuming and costly method development. Additionally, as with many core services, turnaround time can vary, and the price adds up quickly as the number of samples increases. Some cores also require that a minimum number of samples be submitted for each project. One additional concern relevant to both of the aforementioned methods is the difficulty distinguishing myo-inositol from other similar compounds, mainly glucose, which has an identical molecular mass and is a shared substrate of the enzymatic reaction used by most myo-inositol assay kits (21–23). HPLC can be used to measure myo-inositol and has the advantage of being precise, sensitive, and highly reproducible (24–26). However, access to an HPLC system is often limited, and the resources required to purchase, maintain, and train personnel on a new system make this a less-feasible option for many labs.

In light of the limitations outlined above, we developed an alternative approach for assaying myo-inositol that utilizes the auxotrophic phenotype of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain ino1Δ, in which the myo-inositol biosynthetic gene INO1 coding for myo-inositol 3-phosphate synthase is deleted (27). This method takes advantage of the dose-dependent relationship between the myo-inositol concentration in the growth medium and the maximal yeast culture growth density. Previous studies have described methods of utilizing yeast to estimate myo-inositol levels (28,29). However, these methods were published long before technologies such as mass spectrometry could be used to rigorously evaluate their sensitivity. The current approach validates and improves upon previous studies in several aspects. First, the well-characterized myo-inositol auxotrophic strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ino1Δ, was used for this assay, which enabled reliable measurements of myo-inositol levels. Second, the assay was adapted to a 96-well format, which allows the measurement of myo-inositol levels in many samples simultaneously while using minimal sample volumes. Third, this assay is specific for myo-inositol, as the other inositol isomers cannot support growth of the mutant. Lastly, the validity and reliability of the assay were directly demonstrated by comparing values obtained for the same samples using tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). This assay provides a simple, reliable, and affordable method for quantifying myo-inositol levels that will be valuable and accessible to any research group studying myo-inositol metabolism and function.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains

The yeast strains used in this study are from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4741 background and were obtained from Invitrogen. These include: wild-type (MATa, his 3Δ1, leu 2Δ0, met 15Δ0, ura3Δ0) and ino1Δ (MATa, his 3Δ1, leu 2Δ0, met 15Δ0, ura3Δ0ino1Δ::KanMX4).

Culture medium

Cells were maintained on YPD plates (2% bactopeptone, 1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, 2% agar) and cultured in synthetic complete (SC) medium, which contains glucose (20 gr/liter), ammonium sulfate (2 gr/liter), yeast nitrogen base (0.69 gr/liter), adenine (20.25 mg/liter), arginine (20 mg/liter), histidine (10 mg/liter), leucine (60 mg/liter), lysine (20 mg/liter), methionine (20 mg/liter), threonine (300 mg/liter), tryptophan (20 mg/liter), and uracil (40 mg/liter) and myo-inositol-free vitamin mix.

Bioassay procedure

The schematic diagram in Fig. 1 summarizes the following bioassay procedure:

Figure 1. Overview of yeast bioassay methodology.

(1) Grow ino1Δ yeast in a series of myo-inositol dilutions. (2) Track A550 of cultures over 40 hours. (3) Generate standard curve by plotting maximal A550 values against culture myo-inositol concentration. Fit curve with a linear model. (4) Grow ino1Δ yeast supplemented with dilutions of the unknown sample. (5) Plot maximal A550 against dilution factor. (6) Select an A550 value from the linear range and plot against standard curve model to determine myo-inositol concentration in unknown sample. Figure created using BioRender.com

Pre-culture ino1Δ in 10 mL of S.C. medium supplemented with 75 μM myo-inositol in a shaking incubator at 30°C until the stationary phase.

Pellet cells and wash three times with dH2O, then suspend in 10 mL dH2O.

Measure A550 and dilute cell culture to 0.05 A550 in S.C. medium.

Add 180 μL of the 0.05 A550 cell suspension to an appropriate number of wells in the 96-well transparent flat-bottom plate to be used for both the standard curve and testing of unknown samples.

Prepare a series of dilutions of myo-inositol ranging from 10–100 μM in dH2O in intervals of ~10 μM.

Add 20 μL from each of the myo-inositol dilutions (in triplicate) to the cell suspension wells designated for the standard curve.

Prepare a series of dilutions of each unknown sample to be tested using a recommended dilution factor range of 1–100.

Add 20 μL from each of the unknown sample dilutions (in triplicate) to the cell suspension wells designated for unknown sample testing.

Add 200 μL of fresh S.C. medium to three empty wells to be used as blanks.

Incubate at 30 °C with shaking until stationary phase (approximately two days).

Measure A550 using a plate reader and subtract the blank absorbance from all measurements.

Generate a standard curve of ino1Δ growth, measured as A550, relative to myo-inositol concentration.

Fit the standard curve with a linear regression model.

- Determine the myo-inositol concentration in the unknown sample(s) by comparing the A550 of each sample to the modeled standard curve.

- An appropriate dilution for this calculation is determined experimentally. The appropriate dilution(s) will yield an A550 value that falls within the linear range of the myo-inositol standard curve.

Troubleshooting notes:

Lack of access to a shaking incubator or temperature-controlled plate reader: Seeded assay plates can be grown in a stationary incubator and removed to take periodic absorbance readings. When tested, incubation of plate cultures without shaking had no observable effect on maximal culture growth density.

No growth of ino1Δ: If the final myo-inositol concentration in the medium after adding the unknown is below the detection limit of the assay (1 uM), there will be no observable growth of ino1Δ. In this case, it might be necessary to concentrate the sample by drying or using a centrifuge-based concentrator (e.g., a SpeedVac). Alternatively, the ratio of unknown to culture medium could be increased, but this adjustment would need to be corrected for when calculating the absolute inositol concentration.

Assay of myo-inositol using LC-MS/MS

Myo-inositol levels were measured using LC-MS/MS (Pharmacology and Metabolomics Core, Wayne State University). 200 μL of each sample were mixed with 800 μL of MeOH. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 14000 rpm (21952 rcf) for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was dried in a SpeedVac vacuum centrifuge and reconstituted in 300 μL of 80% acetonitrile/20% ddH2O on the day of the assay. A mixture of myo-inositol was prepared to make a standard curve ranging from 5 nM to 20 μM. 100 μL of each sample was mixed with 5 μL of 20 μM myo-inositol-IS (D6) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (C.I.L.) DLM-2725-PK). The samples were analyzed using Waters Xevo TQ-XS coupled with an Acquity H-Class UPLC system. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Waters X-bridge Amide Column (4.6mmX100 mm,3.5 μm) using a gradient elution consisting of mobile phase A (1 mM ammonium acetate, pH 9.0 in 50% ddH2O/50% acetonitrile) and mobile phase B (1 mM ammonium acetate, pH 9.0 in 10% ddH2O/90% acetonitrile),at a flow rate of 0.8mL/min. The elution gradient program was as follows (shown as the time (min), (% mobile phase B)): 0, 50%; 0.4, 50%; 3.3, 0%;3.8, 0%;3.9, 50%; 7, 50%. The column oven temperature was maintained at 50°C. To minimize the carryover, 50% MeOH/50% ddH2O was used as a needle wash solution. Elution of myo-inositol and myo-inositol-D6 were monitored at mass transitions 178.9 > 86.9 and 184.9 > 86.9, respectively. The dwell time, cone voltage, and collision energy of both transitions were set at 0.15 s, 10 V, and 15 eV. The data were acquired and analyzed using Masslynx 4.2 and TargetLynx XS software.

Results

Standard curve of ino1Δ yeast in response to a range of concentrations of myo-inositol

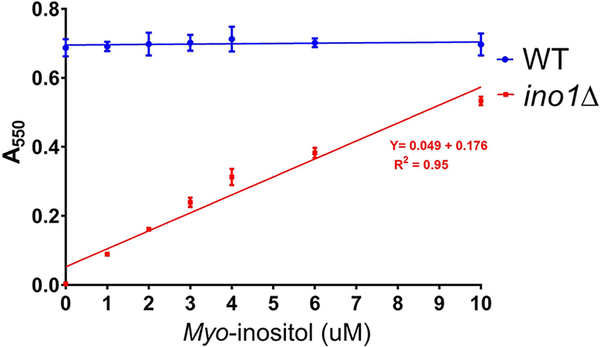

To test the suitability of ino1Δ yeast for the bioassay, cells were cultured in a synthetic complete (S.C.) medium supplemented with a range of myo-inositol concentrations. A550 of each culture was measured at 20 min intervals over 40 hours using a SpectraMax i3x plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA), running an automated growth curve protocol (Fig. 2). The maximal growth density of each culture during the stationary phase was determined using the growth curves in Fig. 2. This was defined as the point at which the increase between subsequent A550 values dropped to less than 0.3% of the previous value for three sequential readings. Next, a standard curve was generated by plotting the maximal growth density values for each culture against the myo-inositol concentration in the corresponding culture medium (Fig. 3). The resulting data demonstrated a positive correlation between the maximal growth density of the yeast culture and the concentration of myo-inositol in the medium (ranging from 0–10 μM; Fig. 3). This relationship showed strong linearity when fitted with a linear regression model (R2 = 0.95). A wild-type (W.T.) yeast strain from the same genetic background was used as a control.

Figure 2. Growth curves of ino1Δ at different myo-inositol concentrations.

Cells were cultured at ~0.05 A550 in 200 μL of SC medium at 30 °C and supplemented with different myo-inositol concentrations as indicated. A550 was measured at 20 min intervals using an automated plate reader protocol. Each data point represents the average A550 of three replicates.

Fig. 3. Standard curve of maximal growth of W.T. and ino1Δ at different myo-inositol concentrations.

W.T. and ino1Δ strains were cultured at 30 °C from a starting density of 0.05 A550 in 96-well plates and supplemented with the indicated myo-inositol concentrations. The maximal attainable growth for each myo-inositol concentration is represented by the A550 reading recorded when the culture reached the stationary growth phase, defined as the point at which the increase between subsequent A550 values from the growth curve (Fig. 2) dropped to less than 0.3% of the previous value for three sequential readings. Each data point represents the average of three replicates ± SD.

As seen in Fig. 3, the growth of W.T. yeast is mostly independent of the medium myo-inositol concentration due to their ability to perform de novo inositol synthesis (Fig. 3). Based on this dose-dependent relationship between ino1Δ yeast growth and myo-inositol concentration, the growth of this strain can be used as a proxy for measuring myo-inositol concentration in unknown samples.

Proof of principle for the bioassay approach was demonstrated using the ino1Δ standard curve shown in Fig. 3 to measure the myo-inositol concentration in various commercially available mammalian cell culture reagents (Table 1). First, the ino1Δ standard curve was fitted with a linear regression to model the relationship between myo-inositol and culture growth. To optimize the fit, data points corresponding to A550 measurements taken after the culture had reached stationary growth were excluded. Next, yeast cultures were set up and supplemented with different dilutions of the selected reagents in water (dilution factors ranged from 1 – 100). The growth of these cultures was tracked until they reached the stationary growth phase, and the maximal A550 value at this point was plotted against the corresponding dilution factor (Fig. 4A). To calculate the myo-inositol concentration for a given reagent, a data point was selected from Fig. 4A that fell within the linear range of the relationship between the dilution factor and the maximal A550 value (bracket above the curve in Fig. 4A). The A550 value for this data point was then plotted on the modeled standard curve from Fig. 3, and the corresponding myo-inositol concentration was determined from the graph (Fig. 4B). To obtain exact values from the model, the A550 value was substituted for y in the linear regression equation and then solved for x using Excel, taking care to correct for the dilution factor.

Table 1.

Myo-inositol levels in cell culture media and sera.

| Sample name | Manufacturer and catalog number | Myo-inositol concentration (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported concentration | Yeast bioassay | (LC-MS/MS) | ||

| DMEM | GIBCO (31053028) | 40 | 37.4 ± 8.13 | 36.50 ± 0.94 |

| Inositol-free DMEM | MP Biomedicals (091642954) | 0 | BD* | BD* |

| Medium 199 | GIBCO (11043023) | 0.278 | BD* | 0.34 ± 0.03 |

| F.B.S. | HyClone, Cytiva (29489343) | - | 29.18 ± 2.90 | 24.92 ± 0.82 |

| Dialyzed F.B.S. ** | HyClone, Cytiva (29489343) | - | B.D.* | B.D.* |

BD: below detection (< 20 nM) for LC-MS/MS analysis) and (< 1 μM) for the yeast bioassay)

Dialysis was performed against water using dialysis membrane tubing Spectra/Por 3 (Repligen) with a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 3.5 kDa for 48 hours. The water in the dialysis container was replaced three times a day.

Figure 4. Calculation of myo-inositol concentration in samples.

A. To calculate the myo-inositol concentration in the sample, yeast cultures are supplemented with increasing dilutions of the unknown sample and the maximum A550 is plotted against the dilution factor. B. Standard curve of maximum A550 against the myo-inositol concentration in the medium. The A550 value to be used for calculating the myo-inositol concentration should fall within the linear range of the standard curve (Fig. 3). Note that the concentration obtained by solving the model for this A550 value should be multiplied accordingly to correct for the dilution factors of both the unknown sample and the standard curve setup. In the example above, this would be 25 for the unknown dilution and 10 for the standard curve (because 20 μL of myo-inositol were added to 180 μL of medium), for a final concentration of 7 μM x 25 × 10 = 1750 μM.

This was repeated for all the reagents in Table 1, and the calculated concentrations were compared to LC-MS/MS analysis and to the manufacturer’s reported myo-inositol concentration (when available) for the same reagent samples. The results demonstrate that the bioassay approach reliably reflects the values obtained through LC-MS/MS. The assay is sensitive in the range of 1 μM to 10 μM.

Discussion

Myo-inositol is essential for the growth and viability of eukaryotic cells (2,30). Myo-inositol is incorporated into inositol phosphates and phosphoinositides, which play a critical role in cell signaling and lipid metabolism (31). Current methods for assaying myo-inositol often suffer from poor data reproducibility, limited instrument accessibility, or high operating costs. Therefore, there is a need for a simple and reliable method for assaying myo-inositol levels.

The ino1Δ yeast strain provides a powerful tool to measure myo-inositol levels in samples because of its dependence on exogenous myo-inositol. The bioassay described here enables the measurement of myo-inositol from various crude sources and is readily adapted to a 96-well plate format for high-throughput measurements. This assay is specific for determining myo-inositol levels, as previous studies have demonstrated that different inositol isomers are not able to support the growth of ino1Δ yeast (32). One caveat of this methodology is that the functional readout is yeast growth, which can potentially be influenced by other components in an unknown sample (e.g., carbon sources, amino acids, toxins, etc.) (33). Nonetheless, comparing the values obtained from this bioassay to those obtained from LC-MS/MS analysis confirmed that the bioassay could consistently determine myo-inositol concentrations in the sensitivity range of 1 μM – 10 μM (Table. 1). This bioassay serves as a reliable and economical tool for assaying myo-inositol levels and will facilitate the rapidly expanding field of research into the regulation and function of myo-inositol biosynthesis.

Highlights.

Myo-inositol is an important metabolite for cell growth

There is a need for a simple, economical method for assaying myo-inositol levels

The yeast ino1Δ strain can be utilized in a novel bioassay approach to measure myo-inositol concentration

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant number R01GM125082 (to M.L.G) and a Rumble Fellowship from the Department of Biological Sciences, Wayne State University (to M.S.). This study utilized the Pharmacology and Metabolomics Core that is supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health grant number P30CA022453 to the Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dominguez A, Villanueva JR, and Sentandreu R (1978) Inositol deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae NCYC 86. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 44, 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eagle H, Oyama VI, and Freeman A (1957) Myo-Inositol as an essential growth factor for normal and malignant human cells in tissue culture. Journal of Biological Chemistry 226, 191–205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry SA, Atkinson KD, Kolat AI, and Culbertson MR (1977) Growth and metabolism of inositol-starved Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 130, 472–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei Y, Iyer S, Costa S, Yang Z, Kramer M, Adelman E, Klingbeil O, Demerdash O, Polyanskaya S, and Chang K (2020) In vivo genetic screen identifies a SLC5A3-dependent myo-inositol auxotrophy in acute myeloid leukemia. bioRxiv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bizzarri M, Fuso A, Dinicola S, Cucina A, and Bevilacqua A (2016) Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of inositol(s) in health and disease. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 12, 1181–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Case KC, Salsaa M, Yu W, and Greenberg ML (2020) Regulation of Inositol Biosynthesis: Balancing Health and Pathophysiology. Handbook of experimental pharmacology 259, 221–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berridge MJ (2014) Calcium signalling and psychiatric disease: bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Cell and Tissue Research 357, 477–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ooms LM, Horan KA, Rahman P, Seaton G, Gurung R, Kethesparan DS, and Mitchell CA (2009) The role of the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases in cellular function and human disease. Biochem J 419, 29–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berridge MJ (2016) The Inositol Trisphosphate/Calcium Signaling Pathway in Health and Disease. Physiol Rev 96, 1261–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artini PG, Di Berardino OM, Papini F, Genazzani AD, Simi G, Ruggiero M, and Cela V (2013) Endocrine and clinical effects of myo-inositol administration in polycystic ovary syndrome. A randomized study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 29, 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papaleo E, Unfer V, Baillargeon JP, De Santis L, Fusi F, Brigante C, Marelli G, Cino I, Redaelli A, and Ferrari A (2007) Myo-inositol in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: a novel method for ovulation induction. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 23, 700–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frej AD, Otto GP, and Williams RS (2017) Tipping the scales: Lessons from simple model systems on inositol imbalance in neurological disorders. European journal of cell biology 96, 154–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falkenburger BH, Jensen JB, Dickson EJ, Suh BC, and Hille B (2010) Phosphoinositides: lipid regulators of membrane proteins. J. Physiol. 588, 3179–3185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logan MR, and Mandato CA (2006) Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton by PIP2 in cytokinesis. Biol Cell 98, 377–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Craene JO, Bertazzi DL, Bar S, and Friant S (2017) Phosphoinositides, Major Actors in Membrane Trafficking and Lipid Signaling Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 18, 634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Homans SW, Ferguson MA, Dwek RA, Rademacher TW, Anand R, and Williams AF (1988) Complete structure of the glycosyl phosphatidylinositol membrane anchor of rat brain Thy-1 glycoprotein. Nature 333, 269–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah A, Ganguli S, Sen J, and Bhandari R (2017) Inositol Pyrophosphates: Energetic, Omnipresent and Versatile Signalling Molecules. J Indian Inst Sci 97, 23–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y, Azab AN, Thompson MN, and Greenberg ML (2006) Inositol phosphates and phosphoinositides in health and disease. in Biology of inositols and Phosphoinositides, Springer. pp 265–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jesch SA, Zhao X, Wells MT, and Henry SA (2005) Genome-wide analysis reveals inositol, not choline, as the major effector of Ino2p-Ino4p and unfolded protein response target gene expression in yeast. Journal of Biological Chemistry 280, 9106–9118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weissbach. (1958) The enzymic determination of myo-inositol. Biochim Biophys Acta 27, 608–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Islam MO, Selvam P, Appukuttan Pillai R, Watkins OC, and Chan SY (2019) An enzymatic assay for quantification of inositol in human term placental tissue. Anal. Biochem. 586, 113409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashizawa N, Yoshida M, and Aotsuka T (2000) An enzymatic assay for myo-inositol in tissue samples. J Biochem Biophys Methods 44, 89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung KY, Mills K, Burren KA, Copp AJ, and Greene ND (2011) Quantitative analysis of myo-inositol in urine, blood and nutritional supplements by high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 879, 2759–2763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence J (1987) Advantages and limitations of HPLC in environmental analysis. Chromatographia 24, 45–50 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong C, You C, Wei P, and Zhang Y-HP (2017) Thermal cycling cascade biocatalysis of myo-inositol synthesis from sucrose. ACS Catalysis 7, 5992–5999 [Google Scholar]

- 26.You C, Shi T, Li Y, Han P, Zhou X, and Zhang YP (2017) An in vitro synthetic biology platform for the industrial biomanufacturing of myo-inositol from starch. Biotechnology and bioengineering 114, 1855–1864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinz FI, Choi MS, Villa-García MJ, and Henry SA (2006) Functional Screening of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Deletion Collection for Ino- and Opi- Phenotypesxs. Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norris F, and Darbre A (1956) The microbiological assay of inositol with a strain of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Analyst 81, 394–400 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woolley D (1941) A method for the estimation of inositol. Journal of Biological Chemistry 140, 453–459 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atkinson K, Kolat A, and Henry S (1976) Mechanism of inositol-less death in yeast. in GENETICS, 428 EAST PRESTON ST, BALTIMORE, MD: 21202 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frej AD, Otto GP, and Williams RSB (2017) Tipping the scales: Lessons from simple model systems on inositol imbalance in neurological disorders. European journal of cell biology 96, 154–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaldubina A, Ju S, Vaden D, Ding D, Belmaker R, and Greenberg M (2002) Epi-inositol regulates expression of the yeast INO1 gene encoding inositol-1-P synthase. Molecular psychiatry 7, 174–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Serio M, Aramo P, De Alteriis E, Tesser R, and Santacesaria E (2003) Quantitative analysis of the key factors affecting yeast growth. Industrial & engineering chemistry research 42, 5109–5116 [Google Scholar]