Abstract

Background

Despite evidence that individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) have a lower risk of mortality when using evidence-based medications for OUD (MOUD), only 20% of people with OUD receive MOUD. Black patients are significantly less likely than White patients to initiate MOUD. We measured the association between various facilitators and barriers to initiation, including criminal justice, human services, and health care factors, and variation in initiation of MOUD by race.

Methods

We used data from a comprehensive, linked data set of health care, human services, and criminal justice programs from Allegheny County in Western Pennsylvania to measure disparities in MOUD initiation by race in the first 180 days after an OUD diagnosis, as well as mediation by potential facilitators and barriers to treatment, among Medicaid enrollees. This is a cross-sectional analysis.

Results

Among 6,374 Medicaid enrollees who met study criteria, Black enrollees were 18.2 percentage points less likely than White enrollees to start MOUD after controlling for gender, age, and Medicaid eligibility (95% CI: −21.5% - −14.8%). Each day in the emergency department or county jail was associated with a decrease in the likelihood of initiation, as was the presence of a non-OUD substance use disorder diagnosis or participation in intensive non-MOUD treatment. Mediators accounted for approximately one-fifth of the variation in initiation related to race.

Conclusions

Acute care facilities and settings in which people with OUD are incarcerated may have an opportunity to increase the use of MOUD overall and close the racial gap in initiation.

Keywords: medication treatment for opioid use disorder, opioid use disorder, racial disparities

1. Introduction

Despite evidence that individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) have a lower risk of all-cause and overdose mortality when using medications for OUD (MOUD) (buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone), only one in five people with OUD receives MOUD (National Academies of Sciences et al., 2019; Park-Lee et al., 2017). The use of MOUD varies by demographic group, geographic communities, and health status. Racial disparities that are widespread in other areas of health are prominent in OUD treatment, and despite the fact that overdose deaths have been rising faster among Black than White Americans, the opioid crisis is still conceptualized as a White epidemic (James and Jordan, 2018). Black patients are significantly less likely than White patients to initiate MOUD — Black patients with OUD may have half the odds of White patients of using buprenorphine or any OUD treatment service (Hadland et al., 2017; Weinstein et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2016).

Racial disparities in OUD treatment may arise from racial differences in interactions with health, human services, and criminal justice systems that are undergirded by structural racism in those systems. For example, racial differences in access to care, interpersonal racism by clinicians, racial differences in criminal justice involvement, and risk of housing instability have all been implicated as potential drivers of disparities in OUD treatment (Kerr et al., 2005; Krawczyk et al., 2017; McKenzie et al., 2012; Mennis and Stahler, 2016). A variety of clinical diagnoses, including diagnoses of mental health disorders, Hepatitis-C Virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may be associated with MOUD initiation (Bodkin et al., 1995; Chan et al., 2014; Dreifuss et al., 2013; Kerr et al., 2005; Lo et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2015; Weinstein et al., 2017). Very little empirical work has examined the extent to which these factors may mediate the relationship between race and MOUD initiation. For example, racial differences in criminal justice system involvement due to racial bias in arrest and incarceration rates are well known, but the extent to which disparities in criminal justice system involvement exacerbate racial disparities in MOUD initiation has not been estimated (The Sentencing Project, 2018; U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2018).

Using comprehensive, linked data that combines individual-level data from health, human services, criminal justice, and other data systems from Allegheny County in western Pennsylvania, this study examines whether the relationship between race and initiation of MOUD is associated with contacts with health and human services and criminal justice systems. We focused on Medicaid enrollees because of the important role Medicaid plays in financing treatment for OUD, especially in states that have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. In 2017, 38% of adults with OUD were covered by Medicaid (Orgera and Tolbert, 2019).

2. Methods

2.1. Data

We used data from the Allegheny County Department of Human Services Data Warehouse from January 1, 2015 to March 31, 2018 (Allegheny County Department of Human Services, 2018). The Data Warehouse links individual-level data from several of the county’s own programs, including two courts and the Allegheny County Jail, and from other data sources, including Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (Appendix). Demographic data on enrollees, including race, age, gender, and Medicaid eligibility pathway were also obtained from the Data Warehouse.

2.2. Study Cohort

Our sample included Allegheny County residents ages 18-64.5 years who were diagnosed with OUD between April 1, 2015 and October 1, 2017, with no recorded diagnosis of OUD in the prior three months. The analysis is limited to enrollees with 180 days of Medicaid enrollment in the days following the index OUD diagnosis.

Due to the demographics of Allegheny County and sample size considerations, we included only non-Hispanic White and Black Medicaid enrollees in this study. Population estimates for Allegheny County in 2019 indicate that 80% of the population is White, 13.4% is Black, 4.1% is Asian, and 2.2% is Hispanic or Latinx. Once study inclusion criteria were applied, the Asian and Latinx populations were too small to support statistical analyses.

2.3. Outcomes

We examined the proportion of enrollees who initiated MOUD in the 180 days after an index OUD diagnosis, categorized by race. This time period both allowed adequate follow-up time and minimized loss to disenrollment from Medicaid. MOUD included buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone and was identified using a combination of physical health, behavioral health, and pharmacy claims paid by Pennsylvania Medicaid and by Allegheny County. Buprenorphine and naltrexone initiation were identified using a mixture of HCPCS procedure codes and NDC codes from physical health, behavioral health, and pharmacy claims. Methadone initiation was identified using procedure codes in behavioral health claims alone, so as to capture methadone dispensed in opioid treatment programs rather than methadone dispensed in pharmacies for treatment of pain (Appendix).

2.4. Covariates

2.4.1. Potential Mediators

Mediation analysis typically implies a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables, which is not appropriate in this analysis; i.e. race is not a cause of initiation of MOUD. Instead, we use mediation methods to understand how much facilitators or barriers to treatment explain variation in the relationship between race and initiation. We constructed mediators based on a review of evidence on 1) the association between race and health diagnoses and public service system contact, and 2) the association between diagnosesand public service system contact and initiation of MOUD. Mediators were measured during the 180-day study period, as this is when they were most likely to impact initiation during that period. We identified three categories of potential mediators of the relationship between race and initiation: criminal justice-related, health-related, and human services. Further detail about the construction of these mediators is available in the Appendix.

Criminal justice-related mediators included days spent in the Allegheny County Jail and days of county court appearances (Magisterial Court and the Court of Common Pleas) for both drug- and non-drug related offenses, including offenses related to driving under the influence, motor vehicles, person, property, public order, weapons, or other criminal or misdemeanor activity. We hypothesized that days spent in the Allegheny County Jail and days with court appearences would decrease the likelihood of initiation. Time spent in jail is a known barrier to MOUD initation, and judges in Allegheny County drug courts do not permit the use of MOUD (Benzing; Krawczyk et al., 2017; Lord).

Human services mediators included a count of months of interaction with county child welfare services, as well as a count of months of interaction with county housing services (including housing assistance, case management, prevention, and outreach provided by DHS and DHS-contracted providers due to a housing crisis) or the receipt of public housing assistance through the City of Pittsburgh or the Allegheny County Housing Authority (Allegheny County Department of Human Services, 2018). We hypothesized that interactions with the child welfare system may have increased the likelihood of MOUD initiation as people attempt to decrease their illicit opioid use and increase their likelihood of retaining custody of their children, and that the receipt of public housing assistance would decrease the likelihood of initiation, as some housing programs or homeless shelters require that residents not use any kind of opioids, including methadone and buprenorphine (Chatterjee et al., 2018; Hall et al., 2016; National Academies of Sciences, 2018; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019).

Health-related mediators included diagnoses of mental health conditions, non-OUD substance use disorders, HCV, and HIV, assessed using ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes available in physical and behavioral health claims, as well as county-funded behavioral health services claims. While literature is mixed on association between HCV and HIV, we hypothesized that the existing relationships with a health care provider would be associated with a greater likelihood of MOUD initiation (HIV InSite; HIV InSite; Murphy et al., 2015; Weinstein et al., 2017). We also included emergency department (ED) visits and inpatient stays, identified using Medicaid claims and county-funded behavioral health services claims. Based on limited existing linkages between acute care settings and opioid treatment providers, we hypothesized that ED visits and inpatient stays would be associated with a lower likelihood of MOUD initiation (Frazier et al., 2017; Larochelle et al., 2018).

We used physical and behavioral health Medicaid claims, as well as county-funded behavioral health services claims, to measure the existence and intensity of non-MOUD SUD-related service use during the study period. We used the Pennsylvania Client Placement Criteria to separate substance use disorder services into “light” treatment (outpatient, intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, and halfway house) and “intensive” treatment (medically monitored detoxification, short-term residential treatment, long-term residential treatment, and medically managed detoxification) categories (PA Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs). Use of non-MOUD treatment for OUD and other SUDs may be related to the severity of OUD or patient or provider preference for certain treatment modalities, or may be related to use of MOUD during the non-MOUD treatment. While the direction of this relationship may vary, we hypothesized that the presence of both light and intensive treatment, as opposed to no treatment, would be associated with an increased likelihood of initiating MOUD.

2.4.2. Controls

Gender and age at the time of OUD diagnosis were identified in enrollment data. Enrollees were classified as qualifying for Medicaid through one of three pathways: the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion, the receipt of Social Security Income (SSI), or another enrollment pathway, primarily composed of enrollees who received Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, time-limited income assistance for families with children) and categorically needy enrollees (who were aged, blind, disabled, or pregnant).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

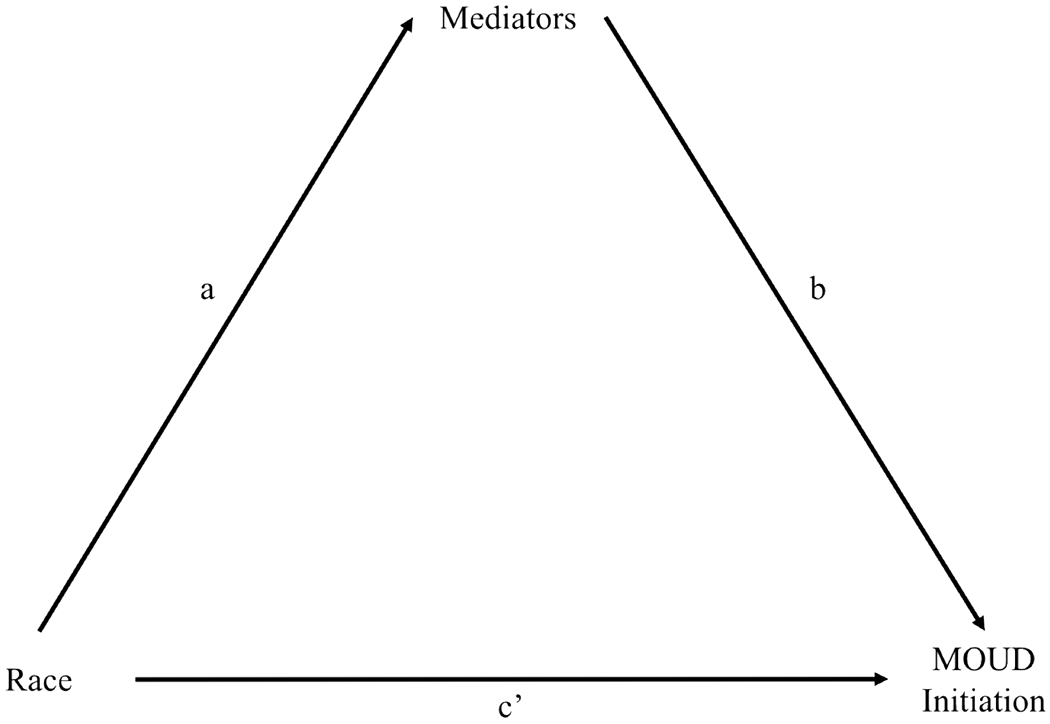

We described demographic characteristics of the cohort and used chi-square tests and t-tests to compare characteristics by race (Table 1). Using a linear probability model (Table 2), we regressed MOUD initiation on a binary race variable, as well as possible mediators of the relationship between MOUD initiation and race, in 5 separate models. In model 1, we regressed initiation on race alone (path c’ in Figure 1). In model 2, we added control variables. In models 3a-1 through 3a-11 (appendix), we regressed race on mediators and on control variables (path a in Figure 1), and in models 3b-1 through 3b-11 (path b in Figure 1), we regressed mediators on the outcome variable. Mediators with which race had a significant relationship in models 3a and a significant association with initiation in models 3b – that is, they were significantly related both to race and to the outcome variable in the presence of controls – were included in model 4, in which we regressed initiation on all relevant mediators and control variables. In model 5, we added interaction terms between possible mediators and race to identify any moderation effect by race. We report coefficients, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values for these coefficients.

Table 1:

Cohort Demographics by Race

| Total | Black | White | p-value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n or mean | % or SD | n or mean | % or SD | n or mean | % or SD | ||

| Size of Groups | 6,374 | 100 | 1,070 | 17.0 | 5,304 | 83.0 | - |

|

| |||||||

| Outcome | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Patient received MOUD within 180 days of OUD diagnosis (n, %)† | 3,004 | 47.1 | 318 | 29.7 | 2,686 | 50.6 | 0.000 * |

|

| |||||||

| Controls | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Gender (n, %) | |||||||

| Female | 2,906 | 45.6 | 411 | 38.4 | 2,495 | 47.0 | 0.000 * |

| Male | 3,468 | 54.4 | 659 | 61.6 | 2,809 | 53.0 | |

| Age Group (n, %) | |||||||

| 18-29 | 1,811 | 28.4 | 189 | 17.7 | 1,622 | 30.6 | 0.000 * |

| 30-39 | 2,183 | 34.2 | 228 | 21.3 | 1,955 | 36.9 | |

| 40-49 | 1,156 | 18.1 | 256 | 23.9 | 900 | 17.0 | |

| 50-64 | 1,224 | 19.2 | 397 | 37.1 | 827 | 15.6 | |

| Eligibility Group (n, %) | |||||||

| Expansion | 2,325 | 36.5 | 299 | 27.9 | 2,026 | 38.2 | 0.000 * |

| SSI | 1,737 | 27.3 | 481 | 45.0 | 1,256 | 23.7 | |

| Other | 2,312 | 36.3 | 290 | 27.1 | 2,022 | 38.1 | |

|

| |||||||

| Potential Mediators in 180 Days After OUD Diagnosis § | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Mental Health Diagnosis (n, %) | 2,266 | 35.6 | 400 | 37.4 | 1,866 | 35.2 | 0.170 |

| Non-OUD SUD Diagnosis (n, %) | 1,710 | 26.8 | 428 | 40.0 | 1,282 | 24.2 | 0.000 * |

| HIV Diagnosis (n, %) | 8 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.012 * |

| HCV Diagnosis (n, %) | 340 | 5.3 | 40 | 3.7 | 300 | 5.7 | 0.011 * |

| Any SUD treatment utilization (non-MOUD) (n, %) | 4,368 | 68.5 | 728 | 68.0 | 3640 | 68.6 | 0.705 |

| Intensive SUD treatment utilization (non-MOUD) (n, %) | 2,367 | 37.1 | 420 | 39.3 | 1947 | 36.7 | 0.116 |

| Days in Allegheny County Jail (Mean, SD) | 8.93 | 31.4 | 14.18 | 40.4 | 7.87 | 29.1 | 0.000 * |

| Days in Court, Drug Offenses (Mean, SD) | 0.12 | 0.4 | 0.08 | 0.3 | 0.13 | 0.4 | 0.001 * |

| Days in Court, Nondrug Offenses (Mean, SD) | 0.21 | 0.5 | 0.18 | 0.5 | 0.22 | 0.6 | 0.029 * |

| Months with Child Welfare Involvement (Mean, SD) | 0.31 | 1.2 | 0.41 | 1.4 | 0.29 | 1.2 | 0.004 * |

| Months with Housing Support (Mean, SD) | 0.39 | 1.4 | 0.99 | 2.1 | 0.27 | 1.2 | 0.000 * |

| Days in Inpatient Setting (Mean, SD) | 0.84 | 4.1 | 1.27 | 5.9 | 0.75 | 3.7 | 0.002 * |

| Days in ED (Mean, SD) | 1.39 | 2.8 | 1.91 | 4.1 | 1.28 | 2.5 | 0.000 * |

P-value for differences in proportions between Black and White enrollees in the cohort. Differences were assessed using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Asterisks indicate statistical significant, p<.05.

MOUD included buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone and was identified using a combination of physical health, behavioral health, and pharmacy claims paid by Pennsylvania Medicaid and by Allegheny County.

We constructed mediators based on a review of evidence on 1) the association between race and health diagnoses and public service system contact, and 2) the association between health status measures and public service system contact and initiation of MOUD.

Table 2:

Initiation Models

| Model Number | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 1 + Controls | 2 + Mediators | 4 + Interactions | |

|

|

||||

| Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | |

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |

| Black race (vs. White) | −0.209** | −0.182** | −0.139** | −0.145** |

| (−0.242 - −0.177) | (−0.215 - −0.148) | (−0.172 - −0.106) | (−0.194 - −0.095) | |

|

| ||||

| Controls: | ||||

| Ages 30-39 (vs. 18-29) | 0.033* | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| (0.003 - 0.064) | (−0.010 - 0.050) | (−0.010 - 0.050) | ||

| Ages 40-49 (vs. 18-29) | 0.047* | 0.031 | 0.031 | |

| (0.010 - 0.084) | (−0.005 - 0.067) | (−0.005 - 0.068) | ||

| Ages 50-64 (vs. 18-29) | 0.053** | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| (0.014 - 0.092) | (−0.023 - 0.054) | (−0.022 - 0.055) | ||

| Male (vs. Female) | −0.035** | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| (−0.060 - −0.010) | (−0.035 - 0.015) | (−0.035 - 0.015) | ||

| SSI Medicaid eligibility | −0.149** | −0.148** | −0.147** | |

| (−0.182 - −0.116) | (−0.180 - −0.116) | (−0.179 - −0.115) | ||

| Expansion Medicaid eligibility | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.017 | |

| (−0.008 - 0.050) | (−0.011 - 0.046) | (−0.012 - 0.046) | ||

|

| ||||

| Possible Mediators: † | ||||

| Non-OUD SUD Diagnosis | −0.049** | −0.039* | ||

| (−0.077 - −0.021) | (−0.070 - −0.007) | |||

| Days in Allegheny County Jail | −0.003** | −0.003** | ||

| (−0.003 - −0.002) | (−0.003 - −0.002) | |||

| Months with Housing Support | −0.009 | −0.006 | ||

| (−0.017 - 0.000) | (−0.017 - 0.005) | |||

| Days in ED | −0.010** | −0.012** | ||

| (−0.015 - −0.006) | (−0.018 - −0.007) | |||

| Intensive SUD treatment utilization (non-MOUD) | −0.080** | −0.082** | ||

| (−0.106 - −0.054) | (−0.110 - −0.054) | |||

|

| ||||

| Black race (vs. White) Interacted with… § | ||||

| Non-OUD SUD Diagnosis | −0.048 | |||

| (−0.116 - 0.021) | ||||

| Days in Allegheny County Jail | 0.001 | |||

| (−0.000 - 0.002) | ||||

| Months with Housing Support | −0.005 | |||

| (−0.023 - 0.013) | ||||

| Days in ED | 0.006 | |||

| (−0.003 - 0.015) | ||||

| Intensive SUD treatment utilization (non-MOUD) | 0.016 | |||

| (−0.051 - 0.083) | ||||

| Constant | 0.506** | 0.524** | 0.602** | 0.603** |

| (0.493 - 0.520) | (0.495 - 0.552) | (0.571 - 0.632) | (0.572 - 0.635) | |

|

| ||||

| Observations | 6,374 | 6,374 | 6,374 | 6,374 |

| R-squared | 0.025 | 0.043 | 0.085 | 0.086 |

| R-squared Adj. | 0.025 | 0.043 | 0.085 | 0.086 |

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Mediators with which race had a significant relationship in models 3a (appendix) and a significant association with initiation in models 3b (appendix) were included in model 4, in which we regressed initiation on all relevant mediators and control variables.

Interaction terms between possible mediators and race to identify any moderation effect by race.

Figure 1:

Mediation Model

Mediation Model. The total relationship between race and MOUD initiation is identified using pathways a, b, and c’. The direct effect is c’. The indirect effect is the product of pathways a and b.

In mediation analyses, we calculated the direct effect (the amount of variation in initiation related to race, taking into account relevant mediators), the indirect effect (the variation in initiation related to race that is explained by mediators), and the total effect (the variation in initiation associated with race without accounting for mediators). We also calculated the proportion of the total effect that goes through the indirect effect (VanderWeele and Vansteelandt, 2014). Confidence intervals for direct, indirect, and total effects, as well as the proportion of indirect to total effect, were bootstrapped. SAS 9.4 and Stata 15.1 were used for data management and statistical analyses (SAS, 2013; StataCorp, 2017).

2.6. Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to confirm the robustness of our primary analysis. First, we used logistic regression instead of a linear probability model to ensure results were robust to model specification. Second, unlike in the primary analysis, in which we included all events that occurred between the date of the OUD diagnosis and 180 days later, this sensitivity analysis modeled initiation by counting only events that occurred between the date of OUD diagnosis and the date of MOUD initiation, including an exposure variable for the days between them (set to 180 for enrollees who did not initiate MOUD). This allowed us to look at exposure to mediators that occurred only prior to initiation as predictors of initiation. Third, we conducted an analysis that incorporated the Medicaid eligibility pathway of the enrollee as a mediator rather than a control. Unlike other mediators, Medicaid eligibility pathway is measured at the start of the study period and is not an occurance during the 180 days. However, the state underlying the pathways (income level, for example) may change over time as is therefore not nearly as immutable as other control variables. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that did not require that the index OUD diagnosis be new.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

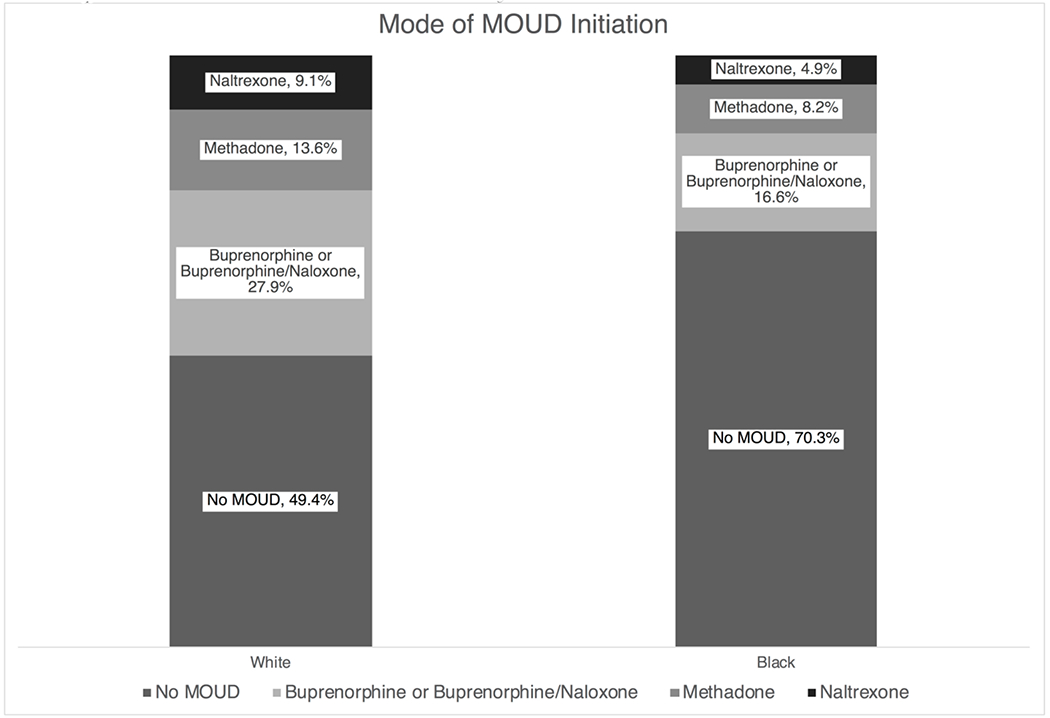

Sample characteristics, stratefied by race, are available in Table 1. Among 6,374 enrollees who met study criteria, 17.0% were Black and 83.0% were White (compared to 40.9% and 42.0% of overall Medicaid enrollees, respectively). Initiation of MOUD differed significantly between racial groups, with 29.7% of Black enrollees initiating MOUD within 180 days of an OUD diagnosis compared to 50.6% of non-Hispanic White enrollees. A majority of enrollees who initiated MOUD used buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone on the first day of MOUD initiation. Among those who initiated MOUD, there are no significant differences in the mode of MOUD initiation between Black and White enrollees (Figure 1). Enrollees were majority male (54.4%) and predominantly between the ages of 30 and 39 (34.2%); however, Black enrollees were much older on average than White enrollees (37.1% of Black enrollees ages 50-64, compared to 15.6% of White enrollees). Black enrollees were more likely than White enrollees to be enrolled in Medicaid through an SSI pathway and less likely through an expansion pathway. On average, Black enrollees spent .63 more days in the ED and .52 more in inpatient settings than White enrollees, and were more likely to be diagnosed with an additional substance use disorder. Black enrollees also spent more days in the Allegheny County Jail (14.2 vs. 7.9), and had .72 more months, on average, of public housing support than their non-Hispanic White counterparts, as well as .12 additional months of interaction with child welfare services. Black enrollees were significantly more likely to have an index diagnosis in the ED, versus inpatient, residential, or other settings (data not shown).

3.2. Models 1-2

Race was significantly associated with the likelihood of initiating MOUD, with Black enrollees 20.9 percentage points less likely to initiate MOUD (29.7% vs. 50.6%, 95% CI: −24.2% - −17.7%, 41.3% less likely) and 18.2 percentage points less likely after gender, age, and Medicaid eligibility controls were added to the model (95% CI: −21.5% - −14.8%) (Table 2, Models 1 and 2).

3.3. Models 3-5

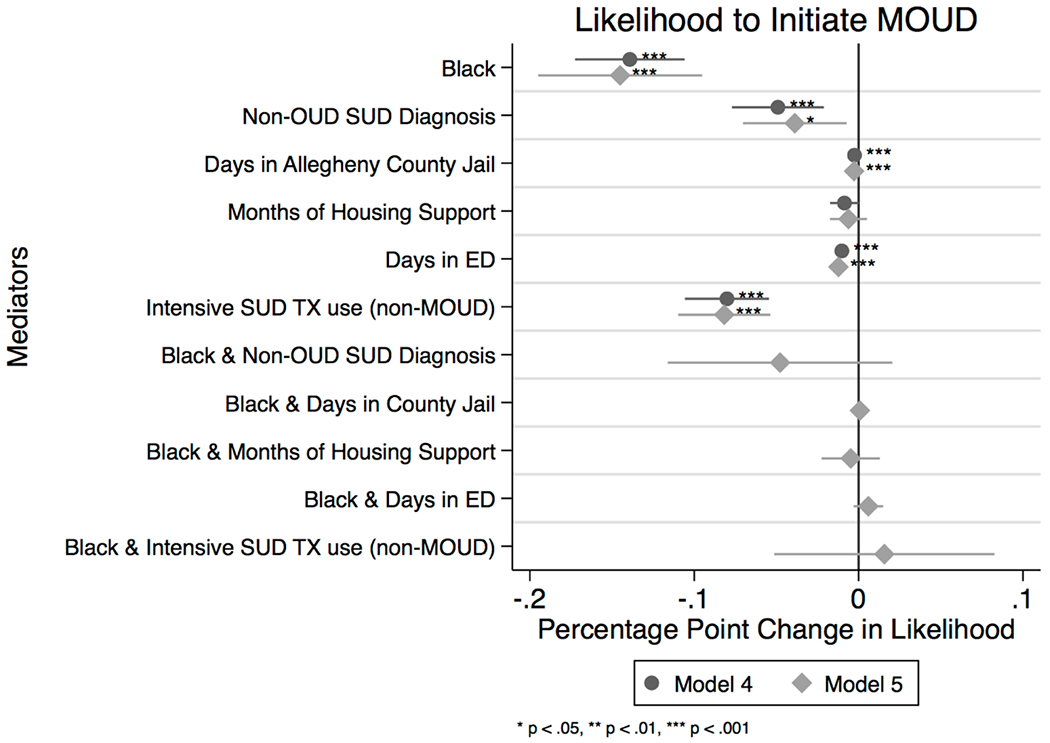

Five mediators met the criteria for being including in the mediation models: having a non-OUD SUD diagnosis, days in Allegheny County Jail, months with housing support, days in the ED, and use of intensive non-MOUD SUD treatment (Appendix). All mediators were associated with Black race (vs. White) and decreased likelihood of MOUD initiation. Having a mental health diagnosis and any use of non-MOUD SUD treatment are associated with increases in the likelihood of MOUD initiation but were not significantly different between Black and White enrollees and therefore did not meet inclusion criteria. When eligible mediators were added to the model, Black enrollees were 13.9 percentage points less likely to initiate MOUD (95% CI: −17.2% - −10.6%) than White enrollees (Table 2, Figure 2). Enrolling in Medicaid through the SSI pathway was associated with a 15 percentage point decrease in the likelihood of initiation (.148, 95% CI: −.180 - −.116), the only statistically significant control. Each day in the ED was associated with a 1 percentage point decrease in likelihood of initiation, and each day in jail was associated with a .3 percentage point decrease. Having a non-OUD SUD diagnosis was associated with a .05 percentage point decrease in initiation, and use of intensive non-MOUD SUD treatment was associated with a .08 percentage point decrease. Together, the mediators account for 23.4% (95% CI: 16.5% - 30.5) of the variation in initiation related to race (Table 3).

Figure 2:

Mode of MOUD Initiation by Enrollee Race

Mode of MOUD initiation by race. A majority of enrollees who initiated MOUD used buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone on the first day of MOUD initiation. Among those who initiated MOUD, there are no significant differences between Black and White enrollees (p>.05).

Table 3:

Mediation Analysis

| Model Number | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 1 + Controls | 2 + Mediators | 4 + Interactions | |

|

|

||||

| Total Indirect Effect (Bootstrapped 95% CI)† | - | - | −0.042** | −0.036* |

| - | - | (−0.053 - −0.031) | (−0.071 - −0.001) | |

| Direct Effect (Bootstrapped 95% CI)§ | - | −0.182** | −0.139** | −0.145** |

| - | (−0.211 - −0.153) | (−0.170 - −0.109) | (−0.196 - −0.095) | |

| Total Effect (Bootstrapped 95% CI)‡ | - | −0.182** | −0.182** | −0.182** |

| - | (−0.211 - −0.153) | (−0.211 - −0.153) | (−0.211 - −0.153) | |

| Proportion of Indirect to Total Effect (Bootstrapped 95% CI)‖ | - | - | 0.233** | 0.201 |

| - | - | (0.163 - 0.303) | (−0.002 - 0.404) | |

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Variation in initiation related to race that is explained by mediators

Variation in initiation related to race, taking into account relevant mediators

Variation in initiation associated with race without accounting for mediators

Proportion of the total effect that goes through the indirect effect

Model 5 included the five mediators included in Model 4, as well as these mediators interacted with the race variable. Black enrollees were 14.5 percentage points less likely to initiate MOUD than White enrollees (95% CI: −19.4% - −9.5%) in this model. Statistically significant mediators from model 4 remained significant in model 5 with only slight changes in coefficient value. None of the mediator-race interactions were statistically significant. Together, all mediators and mediator-race interactions accounted for 20.1% (95% CI: −0.2% - 40.4%) of variation related to race (Table 3)

3.4. Sensitivity Analyses

Using a logistic specification, mediators were identical to those used in Models 4 and 5, and coefficients were the same sign and statistical significance level. We calculated predicted probabilities for race in 4 models and found that that difference between predicted probabilities was nearly identical to the race coefficient in each model (Appendix). Given their similarities, we have retained the linear regression in the main analysis for interpretability.

We modeled initiation by including only events that occurred between the date of OUD diagnosis and the date of initiation and including an exposure variable for the days between them (Appendix). Results supported initial findings that days in the Allegheny County Jail are related to variation in initiation by race. Seven additional mediators are associated with a decreased likelihood of initiating MOUD, including having a health care visit with a mental health, SUD, or HCV diagnosis, days in court for drug-related or non-drug-related offenses, months with child welfare involvement, and any non-MOUD SUD treatment, although some of these effects were slightly attenuated for Black enrollees.

We included Medicaid eligibility pathway as a mediator rather than a control. Results support initial findings that individuals who receive Medicaid via receipt of SSI were 15 percentage points (.148, 95% CI: −.180 - −.115) less likely to initiate MOUD, although this effect was mitigated by 10 percentage points (.101, 95% CI: .023 - .178) for Black enrollees.

Finally, we conducted this analysis with a cohort of individuals whose diagnosis of OUD may not have been new to the previous 3 months, increasing our sample size to 9,421 enrollees. Results were very similar to our primary analysis, indicating that days in the ED, days in the Allegheny County Jail, and time spent in intensive non-MOUD SUD treatment were all associated with a lower probability of initiation MOUD. In addition, Black enrollees with a non-OUD SUD diagnosis were significantly less likely than others to initiate MOUD.

4. Discussion

In Allegheny County, controlling for gender, age, and Medicaid eligibility pathway, there was an 18-percentage point gap between White and Black Medicaid enrollees in the initiation of MOUD. This gap is smaller than estimates in previous research, but differences are still notable (Hadland et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2016). A non-OUD SUD diagnosis, days in the Allegheny County Jail, days in the ED, and the use of intensive non-MOUD SUD treatment were all associated with decreases in MOUD initiation. Using administrative data from the Allegheny Department of Human Services, we were able to explain over 20% of the difference by race in the use of MOUD.

Evidence indicates that MOUD is effective for all subgroups diagnosed with OUD, and there is no apparent clinical reason for a gap in use between Black and White Medicaid enrollees. Our findings underscore the need to focus on acute care facilities to close this gap. Decreases in initiation associated with time spent in EDs may be a proxy for severe OUD or limited engagement in ambulatory care treatment for OUD, as they may be direct consequences of opioid use or withdrawal even if they are not billed as such, or may demonstrate a lack of coordination between these settings and patients’ other providers (Frazier et al., 2017; Larochelle et al., 2018). It is also possible that ED visits are for complications of OUD resulting from a lack of MOUD. Ideally, EDs could provide an opportunity for initiating OUD treatment. A randomized trial of individuals with opioid-positive urine tests found that individuals given buprenorphine in the ED had a higher rate of treatment engagement two months later compared to those who only received a referral to treatment (D’Onofrio et al., 2017). Warm handoffs between the ED and outpatient providers may also alleviate barriers for the patient (Duber et al., 2018). Taking advantage of these opportunities is of paramount importance for improving both overall access to MOUD and racial equity in MOUD initiation because Black enrollees had more days in the ED than White enrollees during the study period. Structural racism has been shown to contribute to differential care in the ED setting and may also contribute to lower rates of MOUD initiation among Black Medicaid enrollees (Corbin et al., 2020; Schnitzer et al., 2020).

Intensive non-MOUD treatment is also associated with lower rates of MOUD initiation. Black enrollees were more likely to receive intensive non-MOUD treatment than White enrollees, which may reflect preferences on the part of patients or providers, or interpersonal and structural racism manifesting in provider bias, and differences in referral to intensive treatment in facilities that do not offer MOUD. Intensive non-MOUD treatment included medically monitored detoxification, short-term residential treatment, and long-term residential treatment. The goal of detoxification programs is often total abstinence from opioids, including opioid agonists like buprenorphine or methadone; however, research suggests high failure rates for medical detoxification within one year (Bailey et al., 2013). And while MOUD is increasingly being offered in residential treatment centers, it is still relatively uncommon, and its use is even more uncommon among Black patients (Mojtabai et al., 2019; Stahler et al., 2021). Increasing the use of MOUD in these facilities will both increase overall access and decrease the racial gap in initiation. An additional SUD diagnosis, also a mediator of the race-initiation relationship and associated with lower probability of initiation, may also be associated with the use of non-MOUD treatment.

A sensitivity analysis demonstrates that a diagnosis of mental illness or HCV between OUD diagnosis and initiation of MOUD are associated with lower likelihood of initiation and mediate the variation by race, contrary to our hypotheses. In particular, while there are mixed findings in the literature regarding the relationship between HCV and MOUD initiation, our study adjusts for a number of non-health care setting factors that may also influence rates of treatment and may not have been available in other studies. These results suggest that other health care providers may have an opportunity to refer their patients to treatment and close the medication treatment disparity between Black and White patients. However, a 2019 survey indicated that only two-thirds of primary care physicians perceived MOUD to be safe for long-term use or more effective than non-medication treatment, and that only one in five were interested in treating patients with OUD (McGinty et al., 2020). Additionally, these diagnoses only reflect the recording of a diagnosis by a provider rather than the presence of a condition, which may itself be subject to racial bias.

Our findings point to time spent incarcerated as a barrier to initiating MOUD. Enrollees who spent 15 or more days in Allegheny County Jail had a predicted 4 percentage point decrease in likelihood of MOUD initiation associated with jailtime alone. Even though MOUD in correctional settings reduces illicit opioid use post-release, as of 2016, Allegheny County Jail, like most jails and prisons across the country, did not offer MOUD (Moore et al., 2019; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019; Silber, 2016). More recently, many jails and prisons, including some in Rhode Island, Vermont, and Massachusetts, are beginning to implement the use of MOUD in these settings, with support from organizations like the National Sheriffs’ Association, the American Correctional Association, and the National Governor’s Association, among others (National Council for Behavioral Health and Vital Strategies, 2020). As the jail incarceration rate for non-Hispanic Black Americans is 3.5 times that for non-Hispanic White Americans, providing access to MOUD in jail and prison settings — and reexamining racial bias in arrests — are important intervention points for limiting racial disparities in MOUD initiation (The Sentencing Project, 2018). As Black Americans also typically receive longer sentences than White Americans for similar crimes, diversion from incarceration settings for those with drug-related crimes or a substance use disorder may also mitigate the racial disparity in MOUD initiation (Rehavi and Starr, 2014).

Research on the factors associated with racial disparities in MOUD can be advanced by increased availability of linked health and human services and other data systems. The United States Department of Health and Human Services has made “better data” part of its five-point strategy to combat the opioid epidemic and recommends, where possible, linking national surveys, claims and electronic health records, and mortality data, among others (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services et al., 2018). In addition to Allegheny County, some state and local governments, including Washington, Maryland, and Massachusetts, have invested in collecting and linking administrative data systems from publicly administered health, human services, and criminal justice systems to inform operational and policy decisions on the opioid crisis and other public health problems.

This study had several limitations. First, the data used in this study are specific to Allegheny County and results may have limited generalizability to other regions, which may not share Allegheny County’s population characteristics or health system features. Second, our analysis relies on administrative data available to Allegheny County during the study period. We cannot account for any additional care received by enrollees that was not financed by Medicaid or Allegheny County. Third, there are many factors unrelated to MOUD that may impact initiation, and some of these may be associated with otherwise unexplained variation by race. We are unable to measure factors like patient and provider preferences and attitudes or within-provider variation, and we are also unable to measure how the impact of region- and neighborhood-level barriers to care varies across racial groups (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019). Accessibility to different modes of MOUD has been shown to vary across neighborhoods, for example (Goedel et al., 2020). These and other ways society fosters structural racism, including compounded stigma around MOUD for Black Americans and the lack of culturally responsive treatment systems, should be explored in future research to better understand and eliminate the racial disparity in MOUD initiation (Allen et al., 2019; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Office of Behavioral Health Equity, 2020). Fourth, due to sample size limitations, we are unable to examine facilitators and barriers to MOUD for Medicaid enrollees who identify as neither non-Hispanic White nor Black. Fifth, this study relies on data from service systems that are likely prone to bias in how services are allocated, treatment is delivered, and diagnoses are assigned. This may introduce bias of an unknown direction into this analysis. Sixth, while we include clinical diagnoses as mediators, there are known racial disparities and evidence of bias in the diagnoses of some conditions, particularly mental health conditions, which may impact our analysis. Finally, this is a cross-sectional study, and this analysis should be interpreted as associative rather than causal.

Factors unrelated to the need for MOUD may impact initiation of MOUD and may be associated with otherwise unexplained variation by race. Using linked administrative data from publicly administered health, human services and criminal justice systems allowed us to explain over 20% of the variation in initiation related to race, but the majority of this variation continues to go unexplained. While additional research explores patient and provider attitudes and within-and between-provider variation, policymakers and payers may consider offering incentives for medication treatment of OUD, particularly in acute care settings and among incarcerated adults, to both increase use of MOUD overall and to close the racial gap.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3:

Likelihood to Initiate MOUD

Mediators of the likelihood to initiate MOUD. A non-opioid SUD diagnosis, days in the Allegheny County Jail, days in the ED, and intensive use of non-MOUD SUD treatment were all associated with a lower likelihood of initiating MOUD in the 180 days after an index OUD diagnosis. All of these conditions were more likely for Black enrollees; however, they do not explain all of the association between race and likelihood to initiate MOUD, as Black enrollees are still >14 percentage points less likely to initiate than White enrollees.

Highlights:

Black Medicaid enrollees 18 percentage points less likely than Whites to start MOUD

Each day in ED or county jail associated with decrease in likelihood of initiation

Mediators accounted for one-fifth of the variation in initiation related to race

Policymakers should focus on acute care and incarceration to close the racial gap

Funding

Dr. Hollander was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health training grant (T32 MH 109436). Dr. Douaihy receives research funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), SAMHSA, HRSA, and Alkermes. This work was partially supported by a grant from the Richard King Mellon Foundation, and pilot funds from the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

Role of Funding Source

The funding sources did not play a role in the conceptualization or writing of this paper.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Douaihy is an employee of the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and receives research funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), SAMHSA, HRSA, and Alkermes. He receives royalties for academic books from Oxford University Press, Springer, and PESI Publishing & Media.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/alleghenycountypennsylvania. (Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Allegheny County Department of Human Services, 2018. Allegheny County Data Warehouse. https://www.alleghenycountyanalytics.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/18-ACDHS-20-Data-Warehouse-Doc_v6.pdf.

- Allen B, Nolan ML, Paone D, 2019. Underutilization of medications to treat opioid use disorder: What role does stigma play? Subst Abus 40(4), 459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey GL, Herman DS, Stein MD, 2013. Perceived relapse risk and desire for medication assisted treatment among persons seeking inpatient opiate detoxification. J Subst Abuse Treat 45(3), 302–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzing J, Allegheny County drug courts render justice, but conflict with some national standards, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Bodkin JA, Zornberg GL, Lukas SE, Cole JO, 1995. Buprenorphine treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 15(1), 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YF, Huang H, Bradley K, Unutzer J, 2014. Referral for substance abuse treatment and depression improvement among patients with co-occurring disorders seeking behavioral health services in primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat 46(2), 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, Yu EJ, Tishberg L, 2018. Exploring opioid use disorder, its impact, and treatment among individuals experiencing homelessness as part of a family. Drug Alcohol Depend 188, 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin TJ, Tabb LP, Rich JA, 2020. Commentary on Facing Structural Racism in Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med 27(10), 1067–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Busch SH, Owens PH, Hawk K, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA, 2017. Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine for Opioid Dependence with Continuation in Primary Care: Outcomes During and After Intervention. Journal of General Internal Medicine 32(6), 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreifuss JA, Griffin ML, Frost K, Fitzmaurice GM, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Selzer J, Hatch-Maillette M, Sonne SC, Weiss RD, 2013. Patient characteristics associated with buprenorphine/naloxone treatment outcome for prescription opioid dependence: Results from a multisite study. Drug Alcohol Depend 131(1–2), 112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duber HC, Barata IA, Cioe-Pena E, Liang SY, Ketcham E, Macias-Konstantopoulos W, Ryan SA, Stavros M, Whiteside LK, 2018. Identification, Management, and Transition of Care for Patients With Opioid Use Disorder in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med 72(4), 420–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier W, Cochran G, Lo-Ciganic WH, Gellad WF, Gordon AJ, Chang CH, Donohue JM, 2017. Medication-Assisted Treatment and Opioid Use Before and After Overdose in Pennsylvania Medicaid. JAMA 318(8), 750–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedel WC, Shapiro A, Cerda M, Tsai JW, Hadland SE, Marshall BDL, 2020. Association of Racial/Ethnic Segregation With Treatment Capacity for Opioid Use Disorder in Counties in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 3(4), e203711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland SE, Wharam JF, Schuster MA, Zhang F, Samet JH, Larochelle MR, 2017. Trends in Receipt of Buprenorphine and Naltrexone for Opioid Use Disorder Among Adolescents and Young Adults, 2001–2014. JAMA Pediatr 171(8), 747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MT, Wilfong J, Huebner RA, Posze L, Willauer T, 2016. Medication-Assisted Treatment Improves Child Permanency Outcomes for Opioid-Using Families in the Child Welfare System. J Subst Abuse Treat 71, 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV InSite, Interactions with Buprenorphine (Suboxone) and Antiretrovirals. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/insite?page=ar-00-02&post=8¶m=89. (Accessed February 3, 2020.

- HIV InSite, Interactions with Methadone and Antiretrovirals. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/insite?page=ar-00-02&post=8¶m=42. (Accessed February 3, 2020.

- James K, Jordan A, 2018. The Opioid Crisis in Black Communities. J Law Med Ethics 46(2), 404–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Marsh D, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E, 2005. Factors associated with methadone maintenance therapy use among a cohort of polysubstance using injection drug users in Vancouver. Drug Alcohol Depend 80(3), 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk N, Picher CE, Feder KA, Saloner B, 2017. Only One In Twenty Justice-Referred Adults In Specialty Treatment For Opioid Use Receive Methadone Or Buprenorphine. Health Aff (Millwood) 36(12), 2046–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, Stopka TJ, Wang N, Xuan Z, Bagley SM, Liebschutz JM, Walley AY, 2018. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder After Nonfatal Opioid Overdose and Association With Mortality: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 169(3), 137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo A, Kerr T, Hayashi K, Milloy MJ, Nosova E, Liu Y, Fairbairn N, 2018. Factors associated with methadone maintenance therapy discontinuation among people who inject drugs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 94, 41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord R, Drug courts divided on approaches to addiction recovery, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, PA. [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Bachhuber MA, Barry CL, 2020. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder: A National Survey of Primary Care Physicians. Ann Intern Med 173(2), 160–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie M, Zaller N, Dickman SL, Green TC, Parihk A, Friedmann PD, Rich JD, 2012. A randomized trial of methadone initiation prior to release from incarceration. Substance abuse 33(1), 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Stahler GJ, 2016. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Outpatient Substance Use Disorder Treatment Episode Completion for Different Substances. J Subst Abuse Treat 63, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Mauro C, Wall MM, Barry CL, Olfson M, 2019. Medication Treatment For Opioid Use Disorders In Substance Use Treatment Facilities. Health Aff (Millwood) 38(1), 14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KE, Roberts W, Reid HH, Smith KMZ, Oberleitner LMS, McKee SA, 2019. Effectiveness of medication assisted treatment for opioid use in prison and jail settings: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat 99, 32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Dweik D, McPherson S, Roll JM, 2015. Association between hepatitis C virus and opioid use while in buprenorphine treatment: preliminary findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 41(1), 88–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK534504/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy, Committee on Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder, 2019. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. National Academies Press; (US: ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019. Medications for opioid use disorder save lives. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Behavioral Health, Vital Strategies, 2020. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in Jails and Prisons: Lessons from the Field. [Google Scholar]

- Orgera K, Tolbert J, 2019. The Opioid Epidemic and Medicaid’s Role in Facilitating Access to Treatment. Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-opioid-epidemic-and-medicaids-role-in-facilitating-access-to-treatment/. [Google Scholar]

- PA Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs, Pennsylvania Client Placement Criteria, Third Edition. http://www.pacdaa.org/Documents/2016CMC/Presentations%20and%20Handouts/2016%20CMC%203B%20and%203C.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Park-Lee E, Lipari RN, Hedden SL, Kroutil LA, Porter JD, 2017. Receipt of services for substance use and mental health issues among adults: results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, CBHSQ Data Review. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; (US: ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehavi MM, Starr SB, 2014. Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Sentences. Journal of Political Economy 122(6), 1320–1354. [Google Scholar]

- SAS, 2013. SAS 9.4. SAS Institute, Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer K, Merideth F, Macias-Konstantopoulos W, Hayden D, Shtasel D, Bird S, 2020. Disparities in Care: The Role of Race on the Utilization of Physical Restraints in the Emergency Setting. Acad Emerg Med 27(10), 943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silber M, 2016. Jail officials, doctors divided on care of opioid-addicted inmates, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Stahler GJ, Mennis J, Baron DA, 2021. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and their effects on residential drug treatment outcomes in the US. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp, 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Behavioral Health Equity, 2020. The Opioid Crisis and the Black/African American Population: An Urgent Issue. No. PEP20-05-02-001. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP20-05-02-001_508%20Final.pdf.

- The Sentencing Project, 2018. Report of The Sentencing Project to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance: Regarding Racial Disparities in the United States Criminal Justice System, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities/.

- U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2018. Prisoners in 2016. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p16.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Health Policy, 2018. Data Sources and Data-Linking Strategies to Support Research to Address the Opioid Crisis. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/259641/OpioidDataLinkage.pdf.

- VanderWeele TJ, Vansteelandt S, 2014. Mediation Analysis with Multiple Mediators. Epidemiol Methods 2(1), 95–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ZM, Kim HW, Cheng DM, Quinn E, Hui D, Labelle CT, Drainoni ML, Bachman SS, Samet JH, 2017. Long-term retention in Office Based Opioid Treatment with buprenorphine. J Subst Abuse Treat 74, 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Zhu H, Swartz MS, 2016. Treatment utilization among persons with opioid use disorder in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend 169, 117–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.