Abstract

bcl-x is a member of the bcl-2 family of genes. The major protein product, Bcl-xL, is a 233-amino-acid protein which has antiapoptotic properties. In contrast, one of the alternatively spliced transcripts of the bcl-x gene codes for the protein Bcl-xS, which lacks 63 amino acids present in Bcl-xL and has proapoptotic activity. Unlike other proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members, such as Bax and Bak, Bcl-xS does not seem to induce cell death in the absence of an additional death signal. However, Bcl-xS does interfere with the ability of Bcl-xL to antagonize Bax-induced death in transiently transfected 293 cells. Mutational analysis of Bcl-xS was conducted to identify the domains necessary to mediate its proapoptotic phenotype. Deletion mutants of Bcl-xS which still contained an intact BH3 domain retained the ability to inhibit survival through antagonism of Bcl-xL. Bcl-xS was able to form heterodimers with Bcl-xL in mammalian cells, and its ability to inhibit survival correlated with the ability to heterodimerize with Bcl-xL. Deletion mutants of Bax and Bcl-2, which lacked BH1 and BH2 domains but contained a BH3 domain, were able to antagonize the survival effect conferred by Bcl-xL. The results suggest that BH3 domains from both pro- and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members, while lacking an intrinsic ability to promote programmed cell death, can be potent inhibitors of Bcl-xL survival function.

Like several other Bcl-2 gene family members, including bcl-2 and bax, the bcl-x gene can encode several protein products as a result of alternative splicing. The longest reading frame encodes Bcl-xL, a protein with high homology to Bcl-2 (1). Like Bcl-2, Bcl-xL has four bcl-2 homology (BH) domains, a region of low homology between BH3 and BH4, the loop domain, and a transmembrane domain at the C terminus. Three other transcripts, known as bcl-x ΔTM, bcl-xβ, and bcl-xγ, are similar to bcl-xL except that these transcripts lack a transmembrane domain at the C terminus (11, 13, 37). These alternatively spliced transcripts produce proteins that are also antiapoptotic. In contrast, the smallest transcript, bcl-xS, which differs from bcl-xL by having 189 bases spliced out, encodes a proapoptotic protein. As a result of this deletion, Bcl-xS lacks BH1 and BH2 domains but still contains BH3, BH4, loop, and transmembrane domains.

Bcl-xS exhibits a more limited tissue distribution than Bcl-xL, which appears to be the most ubiquitously expressed isoform. Bcl-xS has been detected by Western blot analysis in human tonsil, prostate, testis, ovary, and oviduct, as well as in murine basal ganglia (21). bcl-xS mRNA levels have been reported to increase prior to apoptosis in involuting mammary epithelial cells and in ischemic rat brains (8, 15).

Bcl-xS has been shown, in several experimental systems, to be capable of promoting apoptosis. Coexpression of Bcl-xS with Bcl-xL or Bcl-2 reversed the protected phenotype of these transfected cells in response to growth factor deprivation and chemotherapeutic treatment (1, 24, 34). Transgenic mice overexpressing Bcl-xS in keratinocytes demonstrated an increased susceptibility to apoptosis in the skin induced by UV irradiation (28). Infection with an adenoviral vector engineered to encode Bcl-xS resulted in an increased susceptibility of tumor cells to apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo (5, 9, 10). These data all demonstrate the efficacy of Bcl-xS as a negative modulator of cell survival. Bcl-xS lacks the BH1 and BH2 domains, which have been shown to be important in mediating the antiapoptotic function of Bcl-xL (38). These two domains are important not only for heterodimerization with proapoptotic members, such as Bax and Bak, but also for pore-forming properties (30, 31). Like many other proapoptotic family members, Bcl-xS maintains an intact BH3 domain. Unlike any other proapoptotic family member, Bcl-xS also contains a BH4 domain, which has been shown to be important for the antiapoptotic properties of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (16, 17).

To investigate the domain(s) of Bcl-xS necessary to potentiate apoptosis, deletion mutants of Bcl-xS were generated and tested for function in a transient-transfection system. The BH3 domain of Bcl-xS was found to be necessary for the inhibition of the antiapoptotic function of Bcl-xL. The BH3 domains of several other Bcl-2 family proteins were tested and found to share the ability to suppress the survival function of Bcl-xL. These data suggest that the ability to inhibit the antiapoptotic action of proteins such as Bcl-xL is a feature shared by all BH3 domains, including BH3 domains which reside in proteins with antiapoptotic function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

Deletion mutations were generated by PCR mutagenesis and confirmed by sequencing. All Bcl-xS wild-type and deletion constructs had either a FLAG epitope (MDYKDDDDK) or a hemagglutinin (MDYPYDVPDYA) epitope added to the 5′ end by PCR. These constructs were cloned into the plasmid pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene) and subcloned into the EcoRI restriction site of the mammalian expression plasmids pSFFV-Neo and pCDNA 3 (Invitrogen).

Cell culture and transfection.

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s media supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Transfections were carried out in either six-well plates or 10-cm-diameter plates. All death assays were conducted in six-well plates. Cells were seeded at approximately 30% confluency and transfected 24 h later by standard calcium phosphate protocols with the indicated amounts of DNA plus 50 ng of the pEGFP plasmid (Invitrogen), which expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). The quantity of DNA transfected was kept constant for each well or dish transfected throughout each individual experiment. Following transfection, cells were harvested at 15 h for Western blot analysis or 24 h for viability assays. Both adherent and nonadherent cells were collected for cell harvesting. Adherent cells were detached from the plates by incubation with a sterile solution of 5 mM EDTA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Viability assays.

Supernatants and cells were harvested 24 h following transfection. Cells were pelleted and fixed in 1 mM paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Following fixation, cells were repelleted and resuspended in 75% cold ethanol. After a minimum of 1 h of incubation at 4°C, fixed cells were pelleted and resuspended in propidium iodide (PI) staining buffer (3.8 mM sodium citrate, 0.125 mg of RNase A per ml, and 0.01 mg of PI per ml) and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry to measure PI staining of the EGFP-positive cells (22).

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

Cells were harvested 15 h posttransfection. Cells in suspension and adherent cell fractions were combined and pelleted. Cells were lysed in either radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) or NET-N (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris, 0.2% Nonidet P-40) for immunoprecipitations. Lysates were supplemented with 8 μg of aprotinin per ml, 2 μg of leupeptin per ml, and 170 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride per ml. After cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, protein concentrations were assayed by colorimetric bicinchoninic acid analysis (Pierce). Western blot analyses were performed as described previously (2). For FLAG epitope Western blots, membranes were incubated with 1 μg of M2 mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (Kodak) per ml. Bcl-x expression was assayed with either the S-18 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz) at 250 ng/ml or the 13.6 polyclonal antibody at a 1:5,000 dilution. Bax was probed with the N-20 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz) at 250 ng/ml. The 12CA5 mouse monoclonal antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) was used at 1 μg/ml to detect hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tags. Immunoprecipitations were carried out as described previously (2). Briefly, cells were harvested and lysed in NET-N buffer (pH 8.0). Lysates were precleared and incubated with antibody and then incubated with protein G-agarose. Immunoprecipitated proteins were then separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). For every 100 μg of protein, FLAG immunoprecipitations were carried out with 1 μg of M2 antibody per ml, and HA immunoprecipitations utilized 12CA5 antibody (10 μg/ml).

Immunofluorescence staining.

Cells were harvested and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde at 15 h posttransfection. Fixed cells were washed with a 0.03% saponin solution in PBS. M2 antibody staining was conducted with 1 μg/106 cells in a 0.3% saponin solution in PBS supplemented with 20% goat serum. Cells were stained with M2 antibody for 1 h at 4°C, washed with 0.03% saponin, and then incubated with an anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody in 0.3% saponin for 1 h at 4°C. Following secondary-antibody incubation, cells were washed twice with a 0.03% saponin solution, followed by a wash with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter buffer (PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.01% sodium azide). Cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry for fluorescein isothiocyanate expression.

In vitro fluorescence titration assay.

Recombinant BH3 peptide was purchased from PeptidoGenic Research & Co. (Livermore, Calif.) and purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a C8 column. For titration, the fluorescence emission of the Trp residues of Bcl-xL was monitored as a function of increasing peptide concentration. The fluorescence measurements were done on a Shimadzu RF5000U spectrofluorometer with excitation and emission wavelengths of 290 and 340 nm, respectively. The Trp fluorescence intensity was fitted with the equation ΔIobs = Xb × ΔI(b − f), where ΔIobs is the difference between the observed intensity and the fluorescence intensity of the free protein, Xb is the mole fraction of the bound state, and ΔI(b − f) is the fluorescence difference between the bound and free forms of the protein. Mole fractions were calculated from a dissociation constant, Kd, by using the known initial concentrations of the protein and peptide. A least-squares analysis was then performed with systematic variations of Kd and ΔI(b − f). A linear correction for peptide fluorescence was applied to the BH3 peptide prior to data analysis.

Yeast culture and Bax toxicity assay.

Yeast studies were carried out with Saccharomyces cerevisiae W303 (ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1). The yeast cells were maintained on selective synthetic complete medium (1.5 g of U.S. Biological yeast nitrogen base per liter, 5 g of ammonium sulfate per liter, 2 g of amino acid powder mix lacking histidine per liter). Human cDNAs for Bax, the Bax α2 domain, Bcl-xS, and the Bcl-xS α2 domain, all with an N-terminal HA tag, were cloned into the multicopy expression plasmid p423 GALL (histidine selection) controlled by a galactose-inducible promoter (26). Yeast cells were transformed with the p423 GALL expression plasmids by the lithium acetate method and selected on histidine-deficient plates (12). For the Bax toxicity assay, yeast cells were grown at 30°C for 24 h on histidine-deficient plates containing 2% dextrose as a carbon source, after which they were resuspended in histidine-deficient liquid media containing 2% raffinose. The yeasts were then normalized to an optical density of 0.3 at 600 nm, spotted at 10-fold serial dilutions on both histidine-deficient dextrose and histidine-deficient 2% galactose–2% raffinose plates, and allowed to grow at 30°C for 3 to 4 days.

RESULTS

Bcl-xS fails to promote cell death but can reverse Bcl-xL protection.

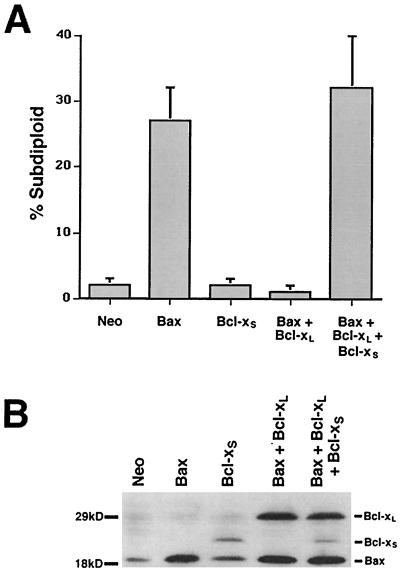

In order to investigate the proapoptotic function of Bcl-xS, the human embryonic 293 kidney epithelial cell line was transiently transfected by using calcium phosphate with expression constructs of various Bcl-2 family members. Cells were cotransfected with an EGFP expression plasmid as a marker for transfection. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were harvested, and the DNA content of the EGFP-positive cells was measured by staining them with PI, followed by flow cytometric analysis (22). For each transfection, 1 μg of each expression construct was used and a quantity of a control vector (Neo) was added to maintain total DNA quantity at 3 μg per transfection. At the concentrations used, Bax induced a sixfold-higher percentage of subdiploid cells than the Neo control vector (Fig. 1A). Equal or greater amounts of Bcl-xS (up to 3 μg per transfection) had no effect on cell viability. The ability of 1 μg of Bax to induce apoptosis was blocked by cotransfection with an equal amount of Bcl-xL. When all three plasmids were cotransfected at 1 μg each, the presence of Bcl-xS reversed the ability of Bcl-xL to inhibit Bax-induced apoptosis. Cotransfection of Bcl-xS with Bax did not enhance Bax-induced apoptosis, and the transfection of Bcl-xL and/or Bcl-xS in the absence of Bax transfection was indistinguishable from that of the Neo control (data not shown). To confirm that the alterations in cell viability correlated with the expression of the transfected proteins, cell lysates of the transfectants were analyzed for protein expression (Fig. 1B). Western blotting confirmed that the expected proteins were observed following transfection and that the levels of individual proteins were similar whether transfected singly or in combination. Although the levels of Bax relative to those of Bcl-xL and Bcl-xS are difficult to estimate since those proteins are detected with distinct antibodies, the levels of Bax transfected alone consistently induced death in 293 cells. In addition, we have found that the levels of Bcl-xS detected by Western blotting with anti-Bcl-x polyclonal antisera relative to those Bcl-xL are consistently underestimated (see below).

FIG. 1.

Bcl-xS can prevent Bcl-xL rescue of Bax-induced cell death. (A) 293 cells, plated in six-well dishes, were transiently transfected with the indicated combinations of constructs, each at 1 μg per transfection. The amount of total DNA per transfection was maintained at 3 μg. Cells were harvested 24 h posttransfection, and the subdiploid percentage of the subpopulation of cells expressing the marker for transfection, EGFP, was measured. Means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments are shown. (B) Transfections were conducted as for panel A, but cells were harvested at 15 h posttransfection. Cells were lysed, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were blotted with a polyclonal anti-Bcl-x antibody and a polyclonal anti-Bax antibody.

The BH3 domain is necessary for the proapoptotic phenotype of Bcl-xS.

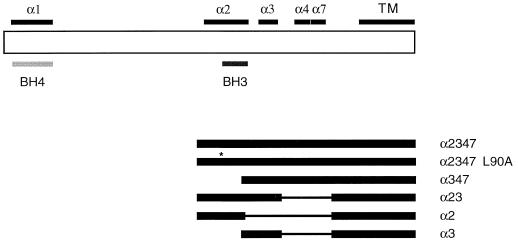

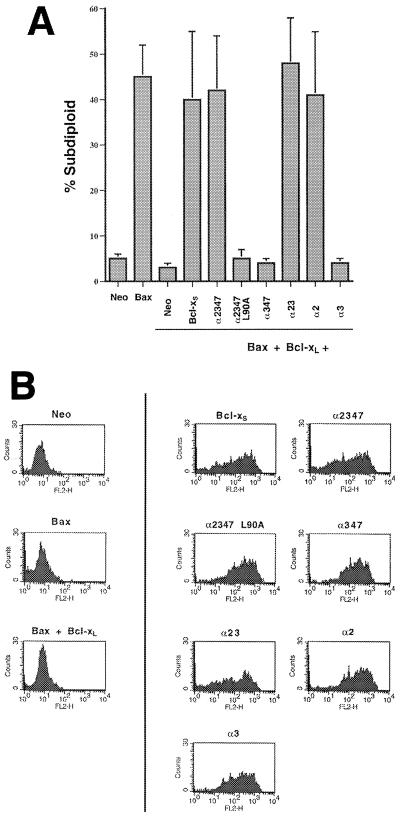

To identify the regions of Bcl-xS important for its inhibition of Bcl-xL function, a series of deletion mutants of Bcl-xS were generated and tested for function in the 293 assay (Fig. 2). With the previously solved structure of Bcl-xL used as a reference, the deletion mutants of Bcl-xS were designed to test the significance of secondary-structure elements found in Bcl-xS. The 63 amino acids in Bcl-xL that are not found in Bcl-xS encompass the core hydrophobic alpha-helices 5 and 6 in Bcl-xL. The primary sequences of the other amphipathic helices are little affected by this deletion and are predicted to maintain their secondary structure in Bcl-xS. The deletion mutants of Bcl-xS were designed to test the contribution of the remaining alpha-helices (α1, α2, α3, and α4) to proapoptotic function. All Bcl-xS constructs contained an N-terminal FLAG epitope tag (MDYKDDDDK) and the wild-type transmembrane domain. Previous work with the Bcl-xL homologue Bcl-2 demonstrated that the C-terminal hydrophobic domain was necessary and sufficient for proper membrane targeting (27). When transfected in the absence of other Bcl-2 family members (at 1 μg per transfection), as in the case of wild-type Bcl-xS, none of the deletion mutants were able to induce apoptosis (data not shown). The Bcl-xS mutants were then tested for their ability to inhibit cell survival in the presence of Bcl-xL and Bax. One microgram each of Bax, Bcl-xL, and the various Bcl-xS deletion mutants was transiently transfected into 293 cells. Analysis of the Bcl-xS deletion mutants revealed that most of the Bcl-xS molecule is dispensable for its proapoptotic function, including the BH4 domain and the loop domain (Fig. 3A). The only region essential for function appeared to be the α2 helix, which encompasses the BH3 domain. Furthermore, a point mutant of Leu 90 in the BH3 domain, which is completely conserved in the BH3 domains of all mammalian Bcl-2 family proteins, is sufficient to inactivate construct α2347. To ensure that differential expression of the deletion constructs was not responsible for the results, the transfectants were intracellularly stained with an anti-FLAG antibody. No significant differences were detected in the expression levels of the different mutants (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of Bcl-xS with deletion mutants of Bcl-xS. (Top) Schematic of Bcl-xS with alpha-helical domains (based on homology to Bcl-xL) highlighted above. TM, transmembrane domain at the C-terminal end of Bcl-xS. (Bottom) Deletion mutants used in this study. Thin lines represent gaps of sequence missing from the deletion constructs. The asterisk identifies the Leu 90-to-Ala point mutation. All constructs, including Bcl-xS, have N-terminal FLAG epitope tags.

FIG. 3.

The BH3 domain is necessary for the proapoptotic phenotype of Bcl-xS. (A) Bax, Bcl-xL, Bcl-xS, and mutants of Bcl-xS were transfected in equal quantities (1 μg each) as indicated. Cells were harvested at 24 h posttransfection, and the subdiploid percentage of the EGFP-positive population was measured. Means and standard deviations of three independent experiments are shown. (B) Transfections were conducted as for panel A. Cells were harvested at 24 h posttransfection, and intracellular staining with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (M2) was performed. Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

The BH3 domains of Bak and Bad were previously shown to be necessary for heterodimerization with Bcl-xL. Furthermore, Bad, the first identified BH3-only-containing family member, is a potent inhibitor of antiapoptotic proteins and manifests its function only through heterodimerization. It seemed highly likely that Bcl-xS, which contains a BH3 domain but does not have a BH1 or BH2 domain, might also mediate its antisurvival phenotype through heterodimerization. Previous reports have yielded conflicting data regarding the heterodimerization capacity of Bcl-xS. Yeast two-hybrid studies suggested that Bcl-xS could heterodimerize with Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 (29, 32). However, Bcl-xS had failed to coprecipitate with Bcl-xL in FL5.12 cell lines (24).

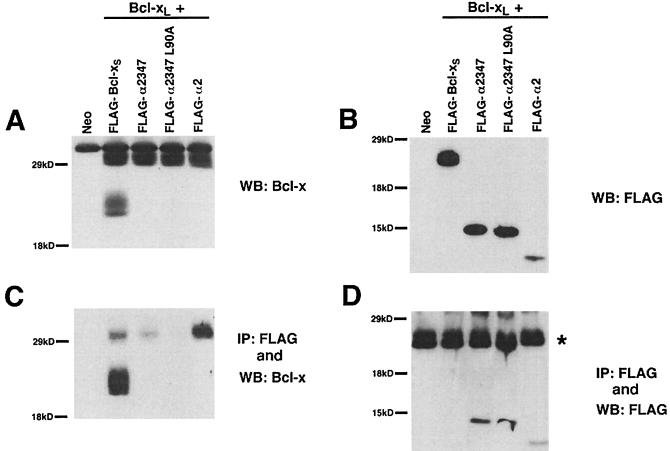

Bcl-xS heterodimerizes with Bcl-xL through its BH3 domain.

To determine whether heterodimerization with Bcl-xL correlated with the phenotype of the various Bcl-xS mutants, equal amounts of Bcl-xL and various Bcl-xS constructs were cotransfected into 293 cells. In addition to wild-type Bcl-xS, three deletion mutants of Bcl-xS were chosen for this assay. Constructs α2347 and α2347 L90A differ only by a point mutation that abolishes α2347 function. The mutant α2, containing the BH3 domain, is the minimal construct which still facilitates apoptosis when coexpressed with Bax and Bcl-xL. Cells were harvested 15 h posttransfection, and the Bcl-xS mutants were immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG antibody against the FLAG epitope present on these constructs. Western blot analyses were performed on both whole-cell lysates and immunoprecipitated proteins to examine the degree of coassociation of Bcl-xL with the Bcl-xS mutants (Fig. 4). In contrast to the results shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 4 shows that the anti-Bcl-x antibody S-18 recognizes Bcl-xS and Bcl-xL equivalently, confirming that roughly equivalent levels of Bcl-xL and Bcl-xS are achieved under these transfection conditions. Unfortunately, this antibody also interacts nonspecifically with a 32-kDa protein. In Fig. 4, the amount of Bcl-xL expressed is constant in all lanes. Since the anti-Bcl-x antibody, S-18, used in these experiments binds to the α1 helix of Bcl-x, it did not recognize the deletion mutants of Bcl-xS. The Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG antibody demonstrated that all the Bcl-xS constructs are expressed roughly equivalently with the exception of α2, which is expressed at a lower level. Immunoprecipitations with the anti-FLAG antibody, followed by Western blotting with the same antibody, demonstrated that the three deletion mutants of Bcl-xS were immunoprecipitated in the same relative ratio as expressed in the whole-cell lysates. As shown in Fig. 4D, Bcl-xS migrated alongside the immunoglobulin light chain of the anti-FLAG antibody used for the immunoprecipitation. This prevented the visualization of Bcl-xS in the anti-FLAG Western blot. Western blot analysis with the S-18 antibody demonstrated the presence of Bcl-xS in the immunoprecipitation. The two functional mutants of Bcl-xS, α2347 and α2, as well as wild-type Bcl-xS, heterodimerized with Bcl-xL, whereas the nonfunctional α2347 L90A mutant did not. Interestingly, the minimal α2 construct, even though underexpressed, heterodimerized with significantly more Bcl-xL than did the other two functional constructs.

FIG. 4.

Heterodimerization with Bcl-xL correlates with the presence of the BH3 domain in Bcl-xS. Cells were transfected with equal amounts of Bcl-xL and Bcl-xS or Bcl-xS deletion mutants. All Bcl-xS constructs had an N-terminal FLAG epitope. Cells were harvested and lysed after 15 h. (A) Western blot analysis of the whole-cell lysates visualized with an anti-Bcl-x antibody (S-18). Note that the deletion mutants of Bcl-xS lack the S-18 epitope. (B) Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates with an anti-FLAG antibody. (C) Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG, and immunoprecipitates were blotted with an anti-Bcl-x antibody (S-18). (D) Western blot analysis with M2 (anti-FLAG) of immunoprecipitates following immunoprecipitation with M2. Note that the immunoglobulin light chain (∗) comigrates with Bcl-xS. WB, Western blot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

Previous in vitro studies failed to find an association of Bcl-xL with a 16-mer peptide encompassing the BH3 domain of Bcl-x. An extended 25-mer peptide spanning the sequence found in the α2 construct (minus the transmembrane domain) was synthesized and tested in the in vitro fluorescence titration assay. Titrations with a 25-mer peptide encompassing the BH3 domain of Bcl-x (residues 80 through 104) bound to Bcl-xL with a Kd of 0.49 ± 0.28 μM, which is of a magnitude comparable to the binding constant of the 16-mer peptide of Bak BH3 to Bcl-xL. This value is 3 orders of magnitude greater than that of the Bcl-x 16-mer peptide composed of residues 84 to 99, which had a Kd of 325 μM. Thus, as was observed with the BH3 domain of Bad, although a minimal BH3 peptide of Bcl-x did not heterodimerize with Bcl-xL, extension of the peptide to encompass the entire alpha-helical domain (α2) resulted in high-affinity binding.

It is possible that Bcl-xS interacts with other Bcl-2 family members, particularly Bax. Bid, another BH3-only family member, has been reported to heterodimerize with Bcl-2 and Bax, leading to the inactivation of Bcl-2 and the potentiation of Bax-induced death (35). To test whether Bcl-xS and Bax interacted, 293 cells were transfected with either FLAG-Bcl-xL or FLAG-Bcl-xS, and the lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody and Western blotted with either anti-Bcl-x antibody or anti-Bax antibody. Bcl-xL interacted with endogenous Bax, as shown previously. However, no significant amount of Bax was detectable in the Bcl-xS immunoprecipitation (data not shown), supporting the yeast two-hybrid data that demonstrated the interaction of Bcl-xS with Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 but not with Bax (32).

BH3 domains from both pro- and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins exhibit an intrinsic antisurvival phenotype.

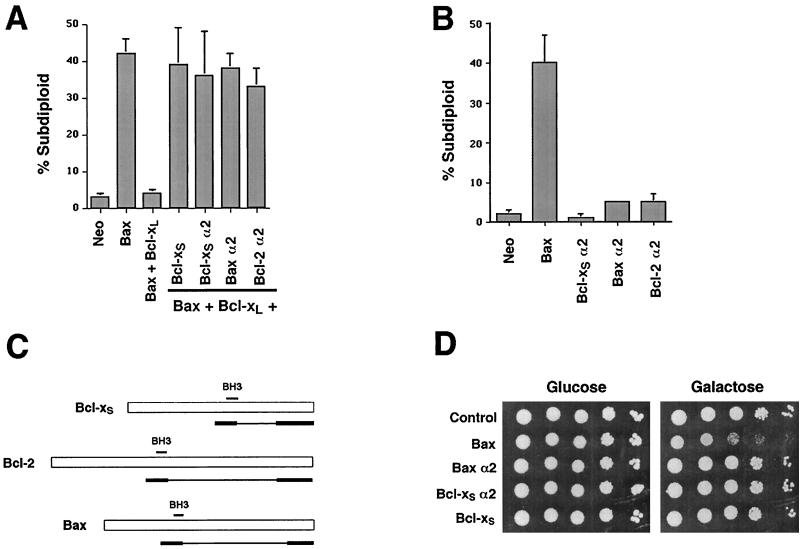

Most studies of the function of BH3 domains have focused on the BH3 domains found in proapoptotic proteins, such as Bak, Bax, and Bad. The studies presented here demonstrate that the BH3 domain found in Bcl-xS, which is identical to the BH3 domain of Bcl-xL, can also antagonize survival through the inactivation of Bcl-xL. This suggested that all BH3 domains might have an intrinsic ability to inhibit survival through heterodimerization with antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members, resulting in their inactivation. To test this possibility, we generated deletion mutants of two additional Bcl-2 family members, Bax and Bcl-2. Relying on the homology between Bcl-xL and these two proteins, the new mutants were designed both to be analogous to α2 (the smallest Bcl-xS deletion mutant which still retained function) and, like Bcl-xS α2, to contain the BH3 domain as well as the putative C-terminal transmembrane domain (Fig. 5). These mutants, designated Bax α2 and Bcl-2 α2, were tested for their ability to antagonize the ability of Bcl-xL to block Bax-induced death in 293 cells (Fig. 5A). As demonstrated previously, wild-type Bcl-xS and the Bcl-xS α2 construct prevented Bcl-xL from protecting against Bax-induced apoptosis. As expected, the α2-containing deletion construct of Bax also prevented Bcl-xL from exerting its survival properties in the presence of Bax. Surprisingly, however, the α2-containing deletion mutant of Bcl-2, an antiapoptotic protein, was also able to block Bcl-xL function under these conditions. As observed with the deletion mutants of Bcl-xS, none of the transfected α2 mutants of Bax and Bcl-2 led to significant apoptosis in the absence of cotransfected Bax, even when the concentration of transfected plasmid was increased threefold (Fig. 5B and data not shown).

FIG. 5.

The α2 helices of Bcl-x, Bax, and Bcl-2 all antagonize Bcl-xL. (A) Cells in six-well dishes were transfected with the indicated constructs, all at 1 μg per transfection. Total DNA concentration was maintained at 3 μg per transfection. The EGFP-positive, subdiploid percentage was measured 24 h after transfection. Means and standard deviations of three independent experiments are shown. (B) Cells were transfected with 1 μg of each indicated construct per transfection. Two micrograms of control vector was used in each transfection. (C) α2 constructs of Bcl-xS, Bcl-2, and Bax. Bold lines represent regions of cDNAs retained in deletion constructs. (D) Yeast cells expressing either Bax, Bax α2, Bcl-xS, or Bcl-xS α2 under the control of a galactose-inducible promoter were grown in the presence of glucose or galactose.

These data demonstrate that a minimal BH3 domain is sufficient to antagonize Bcl-xL, but inadequate in promoting death independently. However, since most mammalian cell lines express multiple Bcl-2 family members, we sought to confirm our results in an independent system in which Bax had been shown to induce cell death in the absence of other coexpressed family members. The yeast S. cerevisiae does not express any known homologues of Bcl-2, and previous work has shown that Bax overexpression in yeast leads to toxicity and growth arrest (39, 40). This toxicity can be blocked by coexpressed Bcl-xL (25). As previously reported, yeast cells overexpressing Bax because of an inducible promoter exhibited a reproducible growth deficit relative to control yeast cells. In contrast, the overexpression of Bcl-xS or the α2 constructs of Bax or Bcl-xS under similar conditions had no effect on the growth of yeast (Fig. 5D). These data support the results obtained in 293 cells, which suggest that BH3-only-containing constructs lack the ability to directly promote cell death.

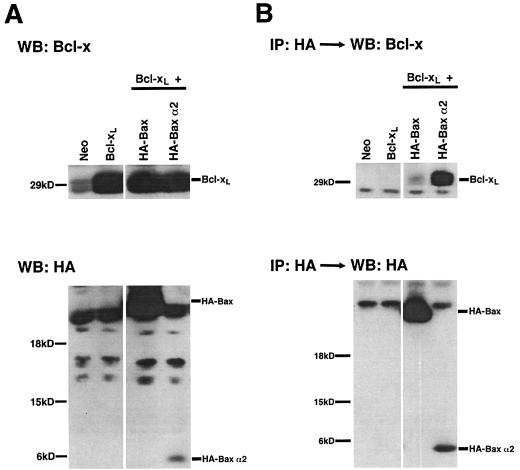

BH3 domain of Bax shows higher affinity for Bcl-xL but cannot promote death independently.

As noted previously, the immunoprecipitation of the α2 construct of Bcl-xS coprecipitated a significantly greater amount of Bcl-xL than did either Bcl-xS or α2347, particularly when the lower levels of expression of α2 relative to the other constructs are taken into account. This fact suggested that the minimal α2 construct might have a higher affinity for Bcl-xL, perhaps due to the lack of steric hindrance which might otherwise be imposed upon the BH3 domain by other domains present in Bcl-xS. To investigate whether increased binding by minimal BH3 domains is a general characteristic of Bcl-2 family proteins, we compared binding affinities of Bax and Bax α2 for Bcl-xL. Both Bax and Bax α2 were N-terminally tagged with the HA epitope. Equal quantities of Bcl-xL and either Bax or Bax α2 expression constructs were cotransfected. Cells were harvested, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with the anti-HA antibody 12CA5. A nonspecific band comigrated with HA Bax to about 21 kD. Similar to the α2 construct of Bcl-xS, the Bax α2 protein was underexpressed relative to wild-type Bax (Fig. 6). The Bax α2 protein heterodimerized with more Bcl-xL than did the wild-type Bax protein. Despite this increased ability to associate with Bcl-xL, Bax α2 lacked the independent cell-killing function in 293 cells displayed by wild-type Bax (Fig. 5). Thus, in this assay, the ability of proapoptotic proteins to heterodimerize with Bcl-xL correlated with an ability to reverse the functional effects of Bcl-xL, but did not appear to reflect a direct proapoptotic function. In contrast, full-length Bax did not require the presence of Bcl-xL to promote death.

FIG. 6.

The α2 helix of Bax heterodimerizes with Bcl-xL to a greater degree than wild-type Bax. (A) Cells plated in 10-cm dishes were transfected with a total of 20 μg of constructs per transfection (10 μg of each construct per transfection). Both Bax and Bax α2 had an N-terminal HA epitope tag. WB, Western blot. There is a nonspecific band in all lanes that migrated close to HA-Bax. (B) Lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted with anti-Bcl-x and anti-HA antibodies. The top panel shows the amount of Bcl-x which coimmunoprecipitates with Bax and Bax α2. The bottom panel is an anti-HA Western blot. The light chain migrated near HA-Bax.

DISCUSSION

The proapoptotic product of the bcl-x gene, Bcl-xS, is a potent antagonist of the antiapoptotic function of Bcl-xL and Bcl-2. Although much work has focused on elucidating the role of the major product of the bcl-x gene, Bcl-xL, relatively little attention has been directed towards Bcl-xS. The studies described here have examined the mechanism of action of Bcl-xS and have identified the BH3 domain as necessary for its function. Furthermore, it was found that BH3 domains, in general, have an ability to block Bcl-xL from functioning. This ability, however, is not sufficient to account for the proapoptotic, death-inducing action of Bax.

It is interesting that Bcl-xS did not induce apoptosis whereas Bax was able to do so. Previous reports have suggested that Bcl-xS can induce apoptosis (5). Furthermore, other family members which lack BH1 and BH2 domains, such as Bik and Hrk, were shown to be able to induce apoptosis in other cell lines by a similar transient transfection protocol (14, 18). However, the overexpression of Bcl-xS at levels that completely inhibit Bcl-xL did not induce apoptosis on its own. This discrepancy in apoptotic induction could be due to many different factors. The simplest explanation might be the differing levels of endogenous apoptosis-regulatory factors in different cell lines. The 293 cells, which were established by adenoviral transformation, express the viral homologue of Bcl-2, the E1B 19,000-molecular-weight (19K) protein. E1B 19K has previously been shown to be resistant to inhibition by Bcl-xS (23). This, however, cannot be the only explanation for the failure of Bcl-xS to cause death independently. Unlike Bax, which contains BH1 and BH2 domains in addition to a BH3 domain, Bcl-xS is unable to induce cell death when overexpressed in 293 cells or when expressed in yeast.

We have shown that the association of Bcl-xS with Bcl-xL is dependent on an intact BH3 domain. The other domain present in Bcl-xS, BH4, is dispensable for its proapoptotic phenotype. As in the case of BH3-only family members, such as Bad, Bik, and Hrk, which lack BH1 and BH2 domains, the proapoptotic function of Bcl-xS appears to be dependent on its ability to heterodimerize and inactivate antiapoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-xL.

The ability of Bcl-xS to heterodimerize had, hitherto, been in dispute. Although the yeast two-hybrid data suggested that Bcl-xS could heterodimerize with Bcl-xL, in vivo experiments failed to show evidence of such interactions (24). There are several significant differences between the experiments described in this study and those previously described. Previous studies on interactions were carried out with the FL5.12 cell line and stable transfectants. The present studies used both a different cell line and a transient-transfection assay, which may have allowed the introduction of higher levels of expression than can be maintained by stable expression. In the FL5.12 cell line, clones expressing high levels of Bcl-xS could not be isolated, whereas clones with highly expressed Bcl-xL were easily generated, suggesting that high levels of Bcl-xS put cells at a growth disadvantage even in the absence of growth factor withdrawal, perhaps due to increased susceptibility to environmental stresses. Furthermore, FL5.12 cells express relatively high levels of endogenous Bax protein, a strong binder of Bcl-xL, which could serve as a possible competitive inhibitor for Bcl-xL–Bcl-xS interactions. In addition, interactions could be influenced by C terminus-dependent targeting. Recent evidence has suggested that the ability of the carboxy terminus to induce the membrane localization of Bax can be regulated in at least some cell lines (36). Finally, the interactions detected in 293 cells were weak in comparison with Bax–Bcl-xL interactions assayed in 35S-labeled FL5.12 cells.

Previous findings demonstrated that Bad, a BH3-only-containing Bcl-2 family member, lacked heterodimerization-independent cell death-promoting activity. Neither wild-type E1B 19K, which does not heterodimerize with Bad, nor functional point mutants of Bcl-xL that failed to bind to Bad were inhibitable by the overexpression of Bad (3, 19). Mutants of Bcl-xS lacking an ability to heterodimerize with Bcl-xL could not reverse the survival function of Bcl-xL, suggesting that heterodimerization is the mechanism through which BH3-only proteins exert their antisurvival properties. Thus, BH3-only proteins may lack independent proapoptotic activity.

Unlike Bcl-xS, proapoptotic proteins with BH1 and BH2 domains, such as Bax, can induce apoptosis irrespective of their ability to associate with antiapoptotic proteins (33). Bcl-xS failed to induce death in 293 cells even when transfected at high levels. Although Bcl-xS and Bax can heterodimerize with and inactivate Bcl-xL, only Bax has the ability to induce apoptosis independently in 293 cells and to cause a growth defect in yeast. Furthermore, the Bax deletion mutant, Bax α2, which lacks the BH1 and BH2 domains of Bax but contains a BH3 domain, has an even greater ability to heterodimerize with Bcl-xL than with wild-type Bax but is unable to induce apoptosis in 293 cells or delayed growth in yeast when expressed alone. Bax α2 is still a functionally active proapoptotic entity, as it was able to antagonize the ability of Bcl-xL to inhibit Bax. These data clearly demonstrate that the death-inducing activity of Bax requires more than heterodimerization to Bcl-xL. One possibility is that the heterodimerization-independent activity and the death-inducing activity of Bax are both dependent on pore formation. Since pore formation is predicted to be dependent on the α5 and α6 helices encompassing the BH1 and BH2 domains (31), which are absent in Bcl-xS and Bax α2, these two constructs would be predicted to lack the ability to form channels in lipid bilayers. Recent data suggest that point mutations in the α5 and α6 helices affect pore-forming properties which can, in turn, influence apoptotic regulation by these proteins (25). Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the deletion of these two helices can have significant effects on the ability of these proteins to independently regulate cell death.

The ability of the BH3 domains from Bax, Bcl-x, and Bcl-2 to facilitate apoptosis to a similar degree suggests that all BH3 domains have an intrinsic ability to inactivate inhibitors of apoptosis (20). An earlier finding demonstrated that the BH3 domains of the proapoptotic proteins Bak, Bax, and Bid, but not that of Bcl-2, could promote apoptosis in Xenopus egg extracts (7). However, the BH3 peptides used in that system were 15-mers, while the minimal α2 constructs used in our assays contained a sequence flanking the α2 helix. As the fluorescence-quenching experiments with Bad and Bcl-x peptides of various lengths demonstrate, the ability of BH3-containing peptides to bind to Bcl-xL can depend on the sequence outside the α2 helix (19). Whether this additional sequence is necessary for specific binding interactions or simply for the stabilization of the core α2 helix is unclear.

The ability of the BH3 domain of Bcl-xS and Bcl-2 to inhibit cell survival in the presence of Bax and Bcl-xL presents an interesting problem. The BH3 domain of Bcl-xS is identical to the BH3 domain of Bcl-xL. Furthermore, unlike Bcl-xS, Bcl-2 has no known alternative-splicing variants which are proapoptotic, yet it still contains a proapoptotic BH3 domain. Clearly, this proapoptotic function of BH3 is subordinate to the antiapoptotic effects of intact Bcl-2. The conversion by caspase cleavage of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL from antiapoptotic to proapoptotic proteins, as recently reported, could be due to enhancement in function or the availability of the BH3 domain resulting from a confirmational change (4, 6). Alternatively, a BH3 domain-only construct may act as a dominant negative. For example, it may be that the BH3 domain is critical for dimerization but additional regions of the protein, including BH1 and BH2, are necessary for prosurvival function. The inactivation of the survival function of Bcl-2 by point mutations in BH1 and BH2 support this possibility (38). BH1 and BH2 domains have been shown to play a critical role in the formation of the hydrophobic binding pocket of Bcl-xL (30). In addition, these domains are necessary for the pore-forming properties of Bcl-xL. Further experiments will need to be conducted to determine if one or both of these functional properties play an important role in the proapoptotic function of Bax or the antiapoptotic function of Bcl-xL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.S.C. and A.K. made equal contributions to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boise L H, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Postema C E, Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka L A, Mao X, Nunez G, Thompson C B. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang B S, Minn A J, Muchmore S W, Fesik S W, Thompson C B. Identification of a novel regulatory domain in Bcl-xL and Bcl-2. EMBO J. 1997;16:968–977. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen G, Branton P E, Yang E, Korsmeyer S J, Shore G C. Adenovirus E1B 19-kDa death suppressor protein interacts with Bax but not with Bad. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24221–24225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.24221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng E H-Y, Kirsch D G, Clem R J, Ravi R, Kastan M B, Bedi A, Ueno K, Hardwick J M. Conversion of Bcl-2 to a Bax-like death effector by caspases. Science. 1997;278:1966–1968. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke M F, Apel I J, Benedict M A, Eipers P G, Sumantran V, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Doedens M, Fukunaga N, Davidson B, Dick J E, et al. A recombinant bcl-xs adenovirus selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells but not in normal bone marrow cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11024–11028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clem R J, Cheng E H, Karp C L, Kirsch D G, Ueno K, Takahashi A, Kastan M B, Griffin D E, Earnshaw W C, Veliuona M A, Hardwick J M. Modulation of cell death by Bcl-xL through caspase interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:554–559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosulich S C, Worall V, Hedge P J, Green S, Clarke P R. Regulation of apoptosis by BH3 domains in a cell-free system. Curr Biol. 1997;7:913–920. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00410-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon E P, Stephenson D T, Clemens J A, Little S P. Bcl-xshort is elevated following severe global ischemia in rat brains. Brain Res. 1997;776:222–229. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dole M G, Clarke M F, Holman P, Benedict M, Lu J, Jasty R, Eipers P, Thompson C B, Rode C, Bloch C, Nunez G, Castle V P. Bcl-xS enhances adenoviral vector-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5734–5740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ealovega M W, McGinnis P K, Sumantran V N, Clarke M F, Wicha M S. bcl-xs gene therapy induces apoptosis of human mammary tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1965–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang W, Rivard J J, Mueller D L, Behrens T W. Cloning and molecular characterization of mouse bcl-x in B and T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1994;153:4388–4398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gietz D, St. Jean A, Woods R A, Schiestl R H. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1425. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.6.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Garcia M, Garcia I, Ding L, O’Shea S, Boise L H, Thompson C B, Nunez G. bcl-x is expressed in embryonic and postnatal neural tissues and functions to prevent neuronal cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4304–4308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han J, Sabbatini P, White E. Induction of apoptosis by human Nbk/Bik, a BH3-containing protein that interacts with E1B 19K. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5857–5864. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heermeier K, Benedict M, Li M, Furth P, Nunez G, Hennighausen L. Bax and Bcl-xs are induced at the onset of apoptosis in involuting mammary epithelial cells. Mech Dev. 1996;56:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)88032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang D C, Adams J M, Cory S. The conserved N-terminal BH4 domain of Bcl-2 homologues is essential for inhibition of apoptosis and interaction with CED-4. EMBO J. 1998;17:1029–1039. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter J J, Bond B L, Parslow T G. Functional dissection of the human Bcl2 protein: sequence requirements for inhibition of apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:877–883. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inohara N, Ding L, Chen S, Nunez G. harakiri, a novel regulator of cell death, encodes a protein that activates apoptosis and interacts selectively with survival-promoting proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. EMBO J. 1997;16:1686–1694. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelekar A, Chang B S, Harlan J E, Fesik S W, Thompson C B. Bad is a BH3 domain-containing protein that forms an inactivating dimer with Bcl-xL. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7040–7046. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelekar A, Thompson C B. Bcl-2-family proteins: the role of the BH3 domain in apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:324–330. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Shabaik A, Wang H G, Irie S, Fong L, Reed J C. Immunohistochemical analysis of in vivo patterns of Bcl-X expression. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5501–5507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamm G M, Steinlein P, Cotten M, Christofori G. A rapid, quantitative and inexpensive method for detecting apoptosis by flow cytometry in transiently transfected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4855–4857. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.23.4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinou I, Fernandez P A, Missotten M, White E, Allet B, Sadoul R, Martinou J C. Viral proteins E1B19K and p35 protect sympathetic neurons from cell death induced by NGF deprivation. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:201–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minn A J, Boise L H, Thompson C B. Bcl-xS antagonizes the protective effects of Bcl-xL. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6306–6312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minn A J, Kettlun C S, Liang H, Kelekar A, Vander Heiden M G, Chang B S, Fesik S W, Fill M, Thompson C B. Bcl-xL regulates apoptosis by heterodimerization-dependent and -independent mechanisms. EMBO J. 1999;18:632–643. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Regulatable promoters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison of transcriptional activity and their use for heterologous expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5767–5768. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen M, Millar D G, Yong V W, Korsmeyer S J, Shore G C. Targeting of Bcl-2 to the mitochondrial outer membrane by a COOH-terminal signal anchor sequence. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25265–25268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pena J C, Fuchs E, Thompson C B. Bcl-x expression influences keratinocyte cell survival but not terminal differentiation. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:619–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato T, Hanada M, Bodrug S, Irie S, Iwama N, Boise L H, Thompson C B, Golemis E, Fong L, Wang H G, et al. Interactions among members of the Bcl-2 protein family analyzed with a yeast two-hybrid system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9238–9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sattler M, Liang H, Nettesheim D, Meadows R P, Harlan J E, Eberstadt M, Yoon H S, Shuker S B, Chang B, Minn A J, Thompson C B, Fesik S W. Structure of Bcl-xL/Bak peptide complex reveals how regulators of apoptosis interact. Science. 1997;275:983–986. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schendel S L, Xie Z, Montal M O, Matsuyama S, Montal M, Reed J C. Channel formation by antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5113–5118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedlak T W, Oltvai Z N, Yang E, Wang K, Boise L H, Thompson C B, Korsmeyer S J. Multiple Bcl-2 family members demonstrate selective dimerizations with Bax. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7834–7838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simonian P L, Grillot D A M, Merino R, Nunez G. Bax can antagonize Bcl-xL during etoposide and cisplatin-induced cell death independently of its heterodimerization with Bcl-xL. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22764–22772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sumantran V N, Ealovega M W, Nunez G, Clarke M F, Wicha M S. Overexpression of Bcl-xS sensitizes MCF-7 cells to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2507–2510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang K, Yin X M, Chao D T, Milliman C L, Korsmeyer S J. BID: a novel BH3 domain-only death agonist. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2859–2869. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolter K G, Hsu Y-T, Smith C L, Nechushtan A, Xi X-G, Youle R J. Movement of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1281–1292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X F, Weber G F, Cantor H. A novel Bcl-x isoform connected to the T cell receptor regulates apoptosis in T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:629–639. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80384-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin X M, Oltval Z N, Korsmeyer S J. BH1 and BH2 domains of Bcl-2 are required for inhibition of apoptosis and heterodimerization with Bax. Nature. 1994;369:321–323. doi: 10.1038/369321a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zha H, Fisk H A, Yaffe M P, Mahajan N, Herman B, Reed J C. Structure-function comparisons of the proapoptotic protein Bax in yeast and mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6494–6508. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zha H, Reed J C. Heterodimerization-independent functions of the cell death regulatory proteins Bax and Bcl-2 in yeast and mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31482–31488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]