Abstract

Simple Summary

Polyphagous leaf-mining flies of the genus Liriomyza are pests that pose a serious threat to agricultural and horticultural industries. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia has been proposed as a useful biocontrol strategy for managing pests, but few studies have so far examined Wolbachia in leafminers. We find a high incidence of related Wolbachia in a survey of infections in 13 dipteran leafminer species collected from Australia and elsewhere which could potentially be useful for the incompatible insect technique (IIT) of pest suppression. We performed curing and crossing experiments on L. brassicae to demonstrate the presence of cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) needed for IIT, providing a foundation for future transfection of CI Wolbachia from L. brassicae to other Liriomyza pests. Overall, these findings highlight a high incidence of Wolbachia in leaf-mining Diptera, potential horizontal transmission events and possible applications of Wolbachia-based biocontrol strategies for Liriomyza pests.

Abstract

The maternally inherited endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis, plays an important role in the ecology and evolution of many of its hosts by affecting host reproduction and fitness. Here, we investigated 13 dipteran leaf-mining species to characterize Wolbachia infections and the potential for this endosymbiont in biocontrol. Wolbachia infections were present in 12 species, including 10 species where the Wolbachia infection was at or near fixation. A comparison of Wolbachia relatedness based on the wsp/MLST gene set showed that unrelated leaf-mining species often shared similar Wolbachia, suggesting common horizontal transfer. We established a colony of Liriomyza brassicae and found adult Wolbachia density was stable; although Wolbachia density differed between the sexes, with females having a 20-fold higher density than males. Wolbachia density increased during L. brassicae development, with higher densities in pupae than larvae. We removed Wolbachia using tetracycline and performed reciprocal crosses between Wolbachia-infected and uninfected individuals. Cured females crossed with infected males failed to produce offspring, indicating that Wolbachia induced complete cytoplasmic incompatibility in L. brassicae. The results highlight the potential of Wolbachia to suppress Liriomyza pests based on approaches such as the incompatible insect technique, where infected males are released into populations lacking Wolbachia or with a different incompatible infection.

Keywords: leaf-mining diptera, agromyzidae, Wolbachia, wsp, MLST, cytoplasmic incompatibility

1. Introduction

The genus Liriomyza is one of the most widely studied and well-documented groups in the Agromyzidae. Since the 1990s, three polyphagous species-Liriomyza huidobrensis (Blanchard), Liriomyza trifolii (Burgess) and Liriomyza sativae Blanchard-have colonized many new areas around the globe [1,2], likely through an increasing international trade in vegetable and horticultural products which has led to their spread on infested plant material [3]. Introduced leaf-mining pests are prone to outbreaks and rapidly become uncontrollable, which has allowed the establishment of these species in most countries [3,4,5,6,7]. This includes Australia, where L. sativae and L. huidobrensis have become established pests and L. trifolii has recently invaded, posing a significant economic threat to Australian agricultural and horticultural industries [8,9,10].

Adults and larvae of Liriomyza flies cause damage to host plants. Female flies damage plants by puncturing the epidermis of host plant leaves with their ovipositor for feeding and egg-laying [11,12]. The leaf punctures also provide entry sites for plant pathogenic bacteria and fungi [13,14,15]. Males and female flies feed on the exudates from the punctures made by females [11]. Most damage is caused by the larval stage tunneling through the palisade and spongy mesophyll cells, producing serpentine mines and reducing the photosynthetic capacity of plants [16], with severely infested leaves falling off plants.

Liriomyza spp. are classic secondary pests, triggered by pest management approaches to control leafminer pests, which routinely rely on insecticide applications [17,18]. Indiscriminate use of broad-spectrum insecticides such as methomyl, methamidophos and permethrin has led to adults evolving insecticide resistance [19,20,21], while larvae are inaccessible to many insecticides because they are embedded in the foliar tissue and pupate in soil [12,22]. There is a higher activity of detoxification enzymes in larvae in comparison to adults, leading to rapid detoxification or sequestration of insecticides [23]. Translaminar insecticides such as abamectin and cyromazine can provide effective chemical control as they penetrate the leaves and kill larvae [24,25]. However, these insecticides have been reported to impact beneficial parasitoid populations [24], they are more expensive than older broad-spectrum insecticides and resistance to these chemicals has been documented [20,21].

Biological control is a safe and sustainable approach that exploits natural enemies (microorganisms, parasitoids, predators and pathogens) to reduce or suppress pest populations [26,27,28]. Augmentative releases of the eulophid parasitoid, Diglyphus isaea (Walker), are widely used for Liriomyza control in ornamental and vegetable greenhouses worldwide [29,30]. The system works well in many vegetable crops because Liriomyza spp. do not attack the harvested produce, and it can also be used successfully for some ornamental crops where mined lower leaves are removed at harvest [30]. In these cases, early releases of parasitoids prevent mining on the upper leaves close to the flowers [30]. Despite this, it can be difficult to establish D. isaea in winter in greenhouses when growth lights attract and kill adult parasitoids [31]. Another challenge is that the sex ratios of commercially reared D. isaea may be extremely male-biased (up to 77% male) [32], resulting in high costs which can make augmentative biological control of leafminers expensive [33,34]. This has led to interest in developing additional control strategies. For instance, releases of sterile L. trifolii males could be undertaken in combination with releases of D. isaea, with synergistic effects suggested in trials on potted chrysanthemums [35].

The incompatible insect technique (IIT) involves endosymbiont-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) when males with an infection mate with females lacking the infection and cause embryonic mortality in filial generations; the CI generated from the repeated release of infected males then leads to a gradual suppression of a target population [36]. Wolbachia represent a group of intracellular endosymbiotic bacteria which are considered the most ideal candidate for IIT. This bacterium can cause CI, male-killing, feminization of genetic males and parthenogenesis induction [37,38]. Among these, CI is the most common phenotype that Wolbachia impose on their hosts [39] and can be either unidirectional or bidirectional [40]. Unidirectional CI can occur when infected males from one strain mate with uninfected females from a different strain while the reciprocal cross is compatible; bidirectional CI can occur when both strains are infected with different Wolbachia and crosses in both directions are incompatible [40].

The ability of Wolbachia to cause CI along with its widespread nature has led to interest in its use as a potential environmentally-friendly biocontrol agent. Studies on IIT to control populations of insect disease vectors and agricultural pests have achieved encouraging results both in the field and laboratory. These include field experiments on Aedes polynesiensis in the South Pacific islands [41], on Culex quinquefasciatus in the south-western Indian Ocean islands [42], on Aedes albopictus in riverine islands in Guangzhou, China [43], and on Ae. aegypti in semi-rural village settings in Thailand [44]. They also include laboratory experiments targeting the medfly Ceratitis capitata [45]. Compared with other sterile insect techniques (SIT) which involve radiation or genetic modification of males, Wolbachia-based IIT seems to impose a relatively low fitness burden on released males and the method is not governed by challenging regulatory pathways [46].

Even though Wolbachia endosymbionts have not yet been used in the control of leaf-mining insects, they have been described from some leafminers including L. trifolii where they cause CI [47,48]. Apart from affecting the reproduction of hosts, Wolbachia may also have other important effects on the life history of leaf-mining herbivorous insects. For instance, in the phytophagous leaf-mining moth, Phyllonorycter blancardella (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) Wolbachia affects host plant physiology, producing the ‘green-island’ phenotype (photosynthetically active green patches) that enhances larval fitness [49]. In addition, Wolbachia can alter mtDNA haplotypes and potentially cause reproductive isolation in leafminers, as recently documented in Phytomyza plantaginis Goureau (Diptera: Agromyzidae) where two mtDNA haplotypes separate parthenogenic and bisexual populations both infected by Wolbachia [50].

Given the potential applications of endosymbionts in pest control, we set out to investigate the incidence of Wolbachia in 13 dipteran leaf-mining species and (by comparing the relatedness of Wolbachia strains against a host phylogeny) the occurrence of horizontal transmission in the Liriomyza group (c.f. Drosophila [51]). We then investigated Wolbachia in Liriomyza brassicae (Riley), a non-pest agromyzid from southern Australia, where we identified a similar Wolbachia as present in the three pest Liriomyza species. We were unable to have cultures of these three species as they are not present in southern Australia. In L. brassicae, we considered Wolbachia density across developmental stages and sexes, and the ability of Wolbachia to generate CI. This initial work represents a first step in a longer-term goal of exploring the feasibility of using Wolbachia-induced CI as a novel environmentally friendly tool for the control of Liriomyza pests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Materials, L. brassicae Cultures and Antibiotic Treatments

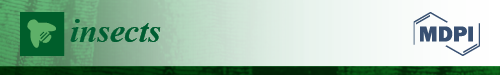

Six agromyzid leaf-mining species (Liriomyza brassicae, Liriomyza chenopodii, Phytomyza plantaginis, Phytomyza syngenesiae, Phytoliriomyza praecellens and Cerodontha milleri) and two drosophilid leafminers (Scaptomyza australis and Scaptomyza flava) were collected from different locations in Australia. Liriomyza brassicae collections were also supplemented by overseas collections from collaborators. Specimens of L. sativae, L. trifolii, L. huidobrensis, L. chinensis and L. bryoniae were obtained from multiple locations and various hosts around the world (Figure 1, Table S1). Specimens were preserved in 95% ethanol and stored at −80 °C or for a few days at −20 °C until use. Species identifications were confirmed by Mallik Malipatil (Agriculture Victoria, AgriBio, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Australia) and verified by DNA barcoding based on mitochondrial COI [8].

Figure 1.

Sampling locations for leaf-mining species in this study. Sampling sites less than 200 km apart were merged, and the colors represent different leaf-mining species. (A) Overall sampling map; (B) Enlarged view of the red frame in (A).

A laboratory-reared strain of Wolbachia-infected L. brassicae was established from individuals collected from Flemington Bridge (latitude −37.787, longitude 144.939) in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. The strain was reared on bok choy (Brassica rapa ssp. chinensis) at 25 °C, 60–70% relative humidity under a photoperiod of 16L:8D in 30 × 30 × 62 cm insect-proof cages. Bok choy was grown from seeds (Eden Seeds, Beechmont, Australia). Plants at 6–7 true leaf stage at one month old (Growth Stage 1–Leaf Production) were used for rearing flies. This population had been maintained in the laboratory for over a year (around 18 generations) at the time of the experiments.

To develop an uninfected L. brassicae strain, we placed a bunch of petioles of developed and healthy bok choy true leaves in 1 mg/mL tetracycline hydrochloride solution in a container (6.5 cm diameter base, 8 cm high) for two days to let leaves fully absorb the solution. The container was wrapped in foil to avoid tetracycline photodegradation. Meanwhile, 20 unmated infected pairs were placed in 35 mL vials (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA) separately and covered with mesh, with honey streaked on the mesh as a food source. Two days later, leaves in good condition (i.e., turgid, unwilted) were provided to 20 pairs of flies separately in polypropylene cups (6.5 cm diameter base, 9 cm diameter top, 14 cm high). The lids of the cups were perforated and covered with mesh. Honey was streaked on the mesh to increase the longevity of mating pairs. We collected female and male individuals from the cups after three days to detect their Wolbachia infection status by using quantitative PCR (qPCR) (see below). Mined bok choy leaves were placed in fresh tetracycline solution until pupae were collected. When the next generation emerged, we selected a subset of flies to check their Wolbachia infection status, and the remaining flies were treated with tetracycline for two further generations following the methods described above. We then established 20 iso-female lines and generated lines from the offspring of parents which were completely cured of Wolbachia as assessed by qPCR (see below, no Wolbachia signal detected). We cultured these lines for another three generations to expand the Wolbachia cured colony.

2.2. Wolbachia Detection in 13 Dipteran Leaf-Mining Species

DNA was extracted from single individuals using the Chelex® 100 resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) method [8]. To confirm infection status, conventional PCR was performed, and the amplification of the wsp (Wolbachia surface protein) gene was taken as evidence of the presence of Wolbachia. The universal primer set was used to obtain wsp sequences, and the amplification was performed following an established protocol (http://pubmlst.org/wolbachia (accessed on 1 June 2021)) [52]. For the species P. plantaginis and P. syngenesiae, new Wolbachia-specific primers were designed to increase the specificity of wsp sequences given that universal primers were not specific enough (Table S2). The PCR thermal conditions were the same as above. PCR products were sent to Macrogen (Seoul, Korea) for purification and Sanger sequencing. Wolbachia infected leafminer specimens verified by sequencing were always included as positive controls, and water was used as a negative control in all Wolbachia screening.

2.3. MLST System for Wolbachia Classification

Wolbachia supergroup designations are routinely used to describe the major phylogenetic subdivisions of this bacterial group [52]. Phylogenetic analyses based on wsp remain the primary methods for Wolbachia supergroup designations [53]. However, due to the level of recombination in Wolbachia pipientis and close relatives, reliable Wolbachia strain characterization requires a multi-locus strain typing (MLST) approach [52,54]. Here, we selected two agromyzid species (P. praecellens and L. brassicae) and used a standard multi-locus strain typing (MLST) approach to validate their supergroup status as determined from the wsp gene. We identified the Wolbachia strains by comparing results with the MLST database. The MLST sequences of these two species were concatenated into a supergene alignment with 2079 nucleotides based on five housekeeping genes (gatB, coxA, hcpA, ftsZ and fbpA), which were amplified with universal primers and the methods followed the published protocol (http://pubmlst.org/wolbachia (accessed on 1 June 2021)) [52]. PCR products were sequenced directly as described earlier.

2.4. Wolbachia Density Estimation in L. brassicae

For rapid monitoring of Wolbachia in L. brassicae, we developed a robust screening assay that was able to simultaneously detect Wolbachia infection and quantify density in L. brassicae. We selected actin as a housekeeping gene due to its stability across developmental stages and sexes [55]. The sequences of the L. sativae actin gene [56] (GenBank No. DQ452369) and L. brassicae wsp gene from this study (GenBank No. MW047082) were used to design specific qPCR primers through an online primer designing tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/ (accessed on 1 June 2021)). A standard curve and sensitivity analyses were applied to assess the performance of the qPCR assay and estimate its efficiency (Figures S1 and S2).

Wolbachia density of L. brassicae in different developmental stages and different generations were quantified using qPCR. Genomic DNA was extracted from F0, F1 and F2 generations of L. brassicae, including the 3rd instar larvae (24 individuals), 5-day-old pupae (24 individuals) and adult flies emerged within 24 h (12 females and 12 males). DNA was extracted as described above and then diluted 1: 2 with DEPC treated water. 2 μL of this diluted DNA was used as a template in real-time quantitative PCR using actin and wsp primers (Table S2). PCR reactions were performed using a Roche LightCycler® 480 system following the cycling conditions outlined by Lee and colleagues [57], except that the annealing temperature was 55 °C for 20 s instead of 58 °C for 15 s (the optimal annealing temperature was determined by conventional gradient PCR in this study). Each sample had three technical replicates, and Cp average values were applied for analyses. Differences between the Cp of the wsp and actin of L. brassicae individuals were transformed by 2[(Cp of actin) − (Cp of wsp)] to obtain approximate estimates of Wolbachia density.

2.5. Crossing Experiments

Individual puparia collected from infected lines and treated lines were put in separate 1.7 mL centrifuge tubes to emerge. In different crossing conditions, crosses were established with a single male and a single female. Sexes of adults were identified under a dissecting microscope, and crosses were performed within 24 h of adult emergence. For each cross, a pair of virgin individuals were put in 35 mL vials (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA). Vials were covered with mesh and honey was streaked onto the mesh to prolong the lifespan of flies. To increase the chance of mating (which normally occurs 10–12 h after emergence [58]), pairs were left for 48 h and then transferred to insect-proof cages (20 cm × 17.5 cm × 12.5 cm) with two developed and healthy bok choy true leaves (one-month-old) placed in a 5.5 cm diameter base × 4 cm diameter top × 10 cm high conical bottle containing water and sealed with parafilm to avoid flies drowning in the water. The lids of cages were cut out and partly covered with mesh so honey could spread on the surface. Three days later, live pairs of flies were placed in 100% ethanol for subsequent validation of the Wolbachia status. The mined leaves were kept in 150 mL polypropylene boxes (FPA Australia Pty Ltd., Melbourne, Australia) lined with paper towel and monitored every day. The number of 1st instar larvae (determined under the microscope), puparia and adults of each sex were counted. Each cross was replicated six times.

2.6. Data Analyses

The wsp sequences were aligned and edited with Geneious 9.1.8 [59]. For phylogenetic analysis, sequences of the wsp gene and MLST genes from a range of species were retrieved from GenBank and analyzed together with our data. The MLST sequences were concatenated into a supergene alignment with 2079 nucleotides. Nucleotide diversity was calculated using DnaSP 6 [60]. The haplotypes detected in the present study were compared with published sequences. Identical sequences were removed from the final data set so that each haplotype was only represented once. The relationship of leafminer species and their corresponding Wolbachia infection was analyzed with maximum likelihood (ML) inference using IQtree 1.4.2 [61]. To assess nodal support, we performed 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates and a SH-aLRT test with 1000 replicates. A MLST phylogenetic tree was generated using the Neighbour-Joining (NJ) method [62] through MEGA X [63] based on Kimura 2-parameter distances with 1000 replicates of bootstrapping [64]. DNA sequences from the present study have been submitted to GenBank.

Statistical analyses of experimental data were performed using SPSS statistics version 24.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Wolbachia densities in the larval and pupal stages of L. brassicae were analyzed using general linear models (GLMs), with life stage and generation included as factors. We performed a separate analysis for Wolbachia density in adults, with sex and generation included as factors. Pairwise comparisons between life stages within a generation were undertaken with t tests. For crossing experiments of L. brassicae, the normal distribution of data was checked with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in Graphpad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). We then used one-way ANOVA tests to compare offspring numbers and sex ratios (after arcsin transformation) between crosses, excluding the cross between Wolbachia-infected males and uninfected females which produced no offspring. We also ran pairwise comparisons (t-tests) to test the effect of tetracycline treatment on the offspring number and sex ratio of offspring from infected and uninfected female parents (when mated with uninfected males) and offspring from infected and uninfected male parents (when mated with uninfected females) to assess any potential effects of antibiotic treatments.

3. Results

3.1. Wolbachia Detection Based on wsp Sequences This Population Had Been Maintained

Leaf-mining species from different populations were tested for Wolbachia infection status through the amplification of a fragment of the wsp gene. We found that all individuals of L. huidobrensis, L. chinensis, L. bryoniae, L. brassicae, L. chenopodii, P. plantaginis, P. syngenesiae, P. praecellens, S. australis and S. flava tested were positive for Wolbachia, while all C. milleri individuals tested negative. For L. trifolii, individuals from four countries (USA (a laboratory colony), Kenya, Timor-Leste and Fiji) were positive for Wolbachia, but those from Indonesia (a recent incursion) were negative. For L. sativae, Wolbachia frequencies differed between populations (Table 1 and Table S1). Of the 27 populations tested for this species, four populations (Sao Bay-Vietnam, Vero Beach-USA (a laboratory colony), Liquisa–Timor-Leste and Ermera-Timor-Leste) showed a high proportion of individuals (>90%) positive for Wolbachia. An additional three populations (Thursday Island–Australia, Seloi Kraik-Timor-Leste and Seloi Malere-Timor-Leste) had only a single individual positive for Wolbachia.

Table 1.

Overall Wolbachia infection rates in leafminer species at the population and individual levels.

| Species | Populations Tested | Populations Positive for Wolbachia | Individuals Tested | Individuals Positive for Wolbachia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liriomyza sativae | 27 | 7/27 | 328 | 44/328 |

| Liriomyza trifolii | 7 | 6/7 | 63 | 51/63 |

| Liriomyza huidobrensis | 4 | 4/4 | 45 | 45/45 |

| Liriomyza bryoniae | 1 | 1/1 | 20 | 20/20 |

| Liriomyza chinensis | 1 | 1/1 | 12 | 12/12 |

| Liriomyza brassicae | 11 | 11/11 | 342 | 342/342 |

| Liriomyza chenopodii * | 5 | 5/5 | 120 | 120/120 |

| Phytomyza plantaginis | 7 | 7/7 | 173 | 173/173 |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | 9 | 9/9 | 360 | 360/360 |

| Phytoliriomyza praecellens * | 1 | 1/1 | 8 | 8/8 |

| Cerodontha milleri * | 2 | 0/2 | 24 | 0/24 |

| Scaptomyza australis * | 3 | 3/3 | 72 | 72/72 |

| Scaptomyza flava | 2 | 2/2 | 12 | 12/12 |

* Species native to Australia.

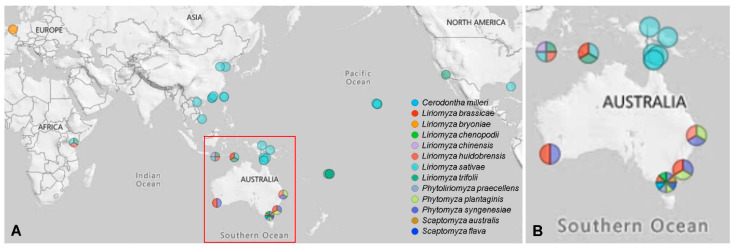

We constructed a maximum likelihood (ML) tree to link different leaf-mining species and their Wolbachia by using the 3′ region of COI for species and partial sequences of the wsp gene. Prior published wsp sequences from other insect species were included to allocate the new infections to Wolbachia supergroups [52] (Figure 2). The sequence alignment based on the wsp sequences suggests the same leaf-mining species can be infected with different Wolbachia strains (Figure 2, Table 2 and Table S3). We found four different wsp alleles (wLsatA, wLsatB, wLsatC and wLsatD) in L. sativae from different populations, which span phylogenetic supergroups A and B. The wsp alleles of L. sativae from Sao Bay (Vietnam) was wLsatC which belongs to Wolbachia subgroup A. On the other hand, wsp alleles of L. sativae from Timor-Leste (containing two Wolbachia alleles: wLsatA and wLsatB) and Thursday Island (wLsatD) belonged to Wolbachia subgroup B. Additionally, the alignment of wsp sequences showed that L. trifolii detected in Kirinyaga (Kenya) was wLtriA, which was different to L. trifolii USA, Fiji and Japan (wLsatD) and Timor-Leste (wLsatA). Furthermore, we found the wsp alleles of L. huidobrensis from Bali (Indonesia) and Nairobi County (Kenya) were wLhuiA, whereas the wsp allele detected in L. huidobrensis from Tarome and Kalabar (Australia) was wLsatA.

Figure 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree to reveal relationships among Wolbachia strains and leafminer species. The phylogeny is inferred by IQTREE based on 3′ end COI sequences of leaf-mining species, and wsp sequences of Wolbachia detected from corresponding leaf-mining species. Published wsp sequences from other insect species were included to allocate the infections to Wolbachia supergroups (the Wolbachia wsp alleles in this study are labeled in bold, additional wsp alleles refer to Baldo et al. [52]). Numbers beside nodes are IQTREE ultrafast bootstrap and SH-aLRT values. ML bootstrap values > 60% are shown on branches.

Table 2.

Wolbachia infection supergroup allocation and allele names corresponding to host species based on Wolbachia wsp sequences.

| Species | Country | Location | Wolbachia Supergroup | Wolbachia wsp Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liriomyza sativae | Timor-Leste | Seloi Malere, Aileu | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza sativae | Timor-Leste | Seloi Kraik, Alieu | B | wLsatB |

| Liriomyza sativae | Timor-Leste | Liquisa, Dato | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza sativae | Timor-Leste | Ermera, Mertutu | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza sativae | Vietnam | Sao Bay | A | wLsatC |

| Liriomyza sativae | Australia | Thursday Island, QLD | B | wLsatD |

| Liriomyza trifolii | USA | California | B | wLsatD |

| Liriomyza trifolii | Kenya | Kirinyaga County | B | wLtriA |

| Liriomyza trifolii | Japan | Shizuoka, Hamamatsu | B | wLsatD |

| Liriomyza trifolii | Timor-Leste | Bazartete, Leoreka | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza trifolii | Japan | Miyagi | B | wLsatD |

| Liriomyza trifolii | Fiji | Qereqere, Sigatoka Valley | B | wLsatD |

| Liriomyza trifolii | Fiji | Wainibokasi, Nausori | B | wLsatD |

| Liriomyza trifolii | Fiji | Koronivia, Nausori | B | wLsatD |

| Liriomyza huidobrensis | Indonesia | Bali | A | wLhuiA |

| Liriomyza huidobrensis | Kenya | Nairobi County | A | wLhuiA |

| Liriomyza huidobrensis | Australia | Tarome, QLD | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza huidobrensis | Australia | Kalabar, QLD | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza bryoniae | Netherlands | Berkel en Rodenrijs | B | wLbryA |

| Liriomyza bryoniae | Japan | Hamamatsu, Shizuoka | B | wLbryB |

| Liriomyza chinensis | Indonesia | Tabanan Regency, Bali | B | wLchiA |

| Liriomyza brassicae | Timor-Leste | Seloi Malere | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza brassicae | Timor-Leste | Seloi Kraik | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza brassicae | Australia | Melbourne locations, VIC a | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza brassicae | Australia | Bruce, ACT | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza brassicae | Australia | Lesmurdie, WA | B | wLsatA |

| Liriomyza chenopodii | Australia | Melbourne locations, VIC b | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza plantaginis | Australia | Flemington Bridge, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza plantaginis | Australia | Glenrowan, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza plantaginis | Australia | Stanhope, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza plantaginis | Australia | Elmore, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza plantaginis | Australia | Romsey, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza plantaginis | Australia | Lismore, NSW | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza plantaginis | Australia | Bruce, ACT | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Flemington Bridge, VIC | A/B | wLsatC/wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Werribee South, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Glen Waverley, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Fitzroy North, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Werribee VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Bruce, ACT | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Yanakie, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Lesmurdie, WA | B | wLsatA |

| Phytomyza syngenesiae | Australia | Ballina, NSW | B | wLsatA |

| Phytoliriomyza praecellens | Australia | Royal Park, VIC | A | wLsatC |

| Scaptomyza flava | Australia | Flemington Bridge, VIC | A | wLhuiA |

| Scaptomyza flava | Australia | Shoreham, VIC | A | wLhuiA |

| Scaptomyza australis | Australia | Royal Park, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Scaptomyza australis | Australia | Flemington Bridge, VIC | B | wLsatA |

| Scaptomyza australis | Australia | Shoreham, VIC | B | wLsatA |

a Includes Flemington Bridge, Gladstone Park, Northcote, Fitzroy North, Thomastown, Werribee and Werribee South populations. b Includes Flemington Bridge, Werribee, Werribee South, Glen Waverley, Fitzroy North and Werribee populations. QLD = Queensland, VIC—Victoria, ACT = Australian Capital Territory, WA = Western Australia, NSW = New South Wales.

At the same time, our results suggest that different leaf-mining species may share the same Wolbachia strain (Figure 2, Table 2 and Table S3). The sequence alignment results based on wsp indicated that Wolbachia alleles from P. praecellens from Royal Park (Australia) and L. sativae from Sao Bay (Vietnam) were both wLsatC. wLsatA was the most common allele, shared by eight leaf-mining species (L. huidobrensis, L. sativae, L. trifolii, L. brassicae, L. chenopodii, P. plantaginis, P. syngenesiae and S. australis). We also found that the Wolbachia allele in L. trifolii (California-USA, and Fiji) and in L. sativae (Thursday Island-Australia) were identical to the sequence from L. trifolii mentioned in Tagami et al. [47] when comparing their wsp sequences (wLsatD). It is worth noting that there is only a single base-pair difference between wLsatA and wLsatD. Moreover, the wsp allele of L. huidobrensis (Indonesia and Kenya) and S. flava (Australia and Hawaii) were both wLhuiA, which suggests that L. huidobrensis and S. flava may share the same Wolbachia strain. Interestingly, Wolbachia superinfections were detected in P. syngenesiae in one population (Flemington Bridge–Australia) based on sequencing data; we found 192 individuals were infected with wLsatA as determined from screens with primers specific to this infection, but three of these individuals were diagnosed as having two different wsp alleles (wLsatA and wLsatC) based on universal primers. In eight other Australian populations, only one allele (wLsatA) was found in P. syngenesiae (Table 2 and Table S3).

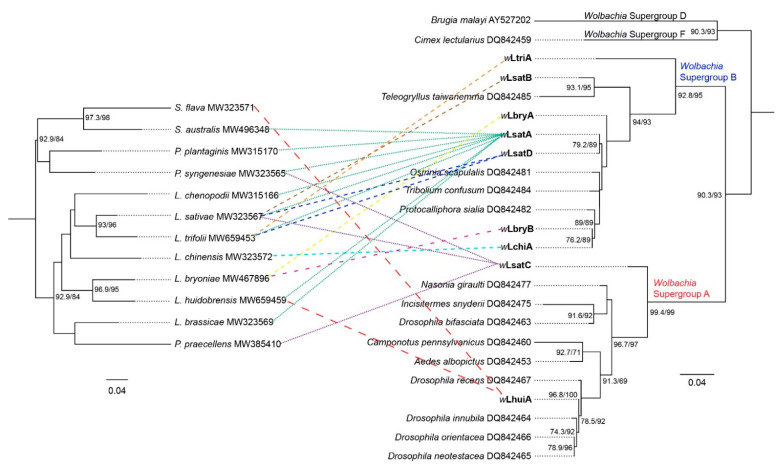

3.2. MLST System for Wolbachia Classification

Our study demonstrates that the MLST phylogenetic analyses were consistent with the above wsp phylogenetic analyses; the Wolbachia from P. praecellens was allocated to the A-supergroup, and the infection from L. brassicae was allocated to the B-supergroup (Figure 3). Allelic profiles for the five housekeeping genes of Wolbachia from P. praecellens were (22) gatB, (23) coxA, (24) hcpA, (3) ftsZ and (23) fbpA. A comparison of sequences from the five MLST genes with those in the databases was consistent with the notion that the Wolbachia strain detected in P. praecellens represents Dsim_A_wRi, which was also identified in Drosophila simulans and shows CI [52,65]. For L. brassicae, the five allelic profiles were (9) gatB, (280) coxA, (40) hcpA, (7) ftsZ and (9) fbpA. A comparison of sequences from the five MLST genes with those in the databases suggested that this Wolbachia strain represented a new strain, which we have named Lbra_B_1.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic placement of Wolbachia from two leaf-mining species (Phytoliriomyza praecellens and Liriomyza brassicae) collected in Australia based on MLST genes within a collection of insects taken from Baldo et al. [52]. The neighbor-joining tree (K2P model, 1000 bootstrap replicates) is based on multiple alignments of concatenated DNA sequences encoding the coxA, fbpB, ftsZ, gatB and hcpA genes. Bootstrap values are shown for all nodes. ML bootstrap values > 60% are shown on branches. The two species included in this study are shown in bold.

3.3. Wolbachia Density Estimation in L. brassicae

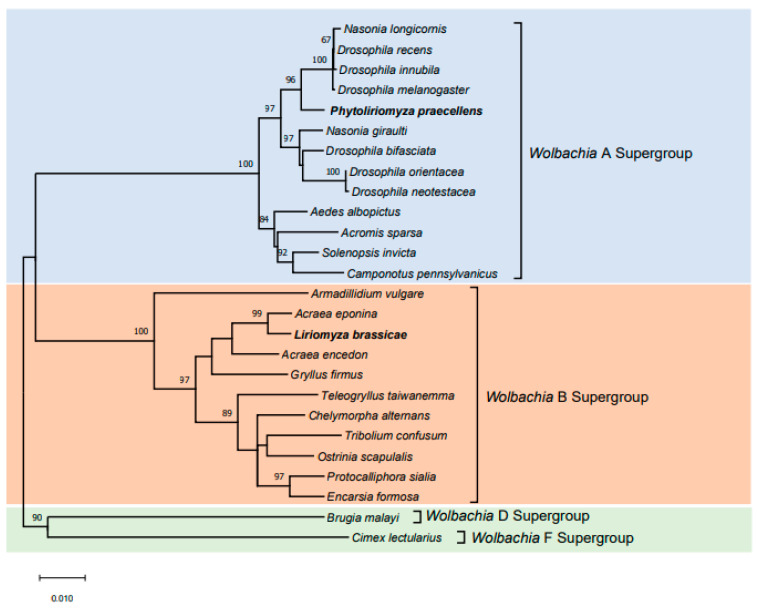

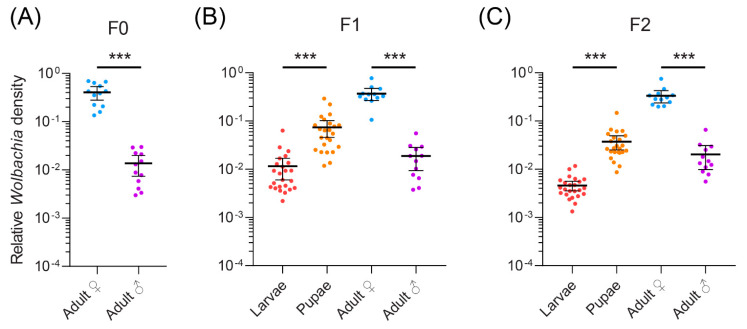

Given that Wolbachia strain Lbra_B_1 is prevalent among different leaf-mining species, we selected L. brassicae as a model species to investigate its Wolbachia density across different generations and developmental life stages. Wolbachia density was quantified using qPCR. In adults, Wolbachia density was stable across three generations, with no significant effect of generation on density (General Linear Model: F2,66 = 0.194, p = 0.824). However, Wolbachia density differed between the sexes, with females having a higher density than males (F1,66 = 416.216, p < 0.001) (Figure 4). This difference was evident in each generation (Figure 4). Wolbachia density increased during development, with higher densities in puparia compared with larvae (F1,92 = 186.528, p < 0.001), a difference that was evident in both the F1 and F2 generations (Figure 4) There was also a significant effect of generation in this comparison, with higher densities in the F1 generation compared with the F2 generation (F1,92 = 18.274, p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Wolbachia density in (A) F0, (B) F1 and (C) F2 generations across different developmental stages and sexes of Liriomyza brassicae. Dots represent data from individual flies while horizontal lines and error bars are means and 95% confidence intervals. Data are shown on a log scale. Significance levels for comparisons between sexes and life stages within a generation are shown (t-tests, ***, p < 0.001).

3.4. Crossing Experiment of L. brassicae

To determine the influence of Wolbachia infection on L. brassicae, we performed reciprocal crosses between Wolbachia-infected and treated individuals. High hatching rates were observed when the crosses were performed between the same strains or between infected females and treated males (Table 3). The number of larvae/puparia/adults did not differ between crosses when the incompatible cross was excluded (One-way ANOVA: larvae: F2,15 = 0.413, p = 0.669; puparia: F2,15 = 0.566, p = 0.580; Adults: F2,15 = 0.448, p = 0.648). The emergence rate of adults in these crosses was also relatively high, while sex ratios did not differ significantly from 1:1 in any cross where flies emerged (t-test, theoretical mean of 50% males or females, all p > 0.05). However, no leafmines were observed in crosses between infected males and treated females, and no offspring emerged, indicating complete CI (Table 3).

Table 3.

Crossing experiments to detect the influence of Wolbachia infection on Liriomyza brassica offspring. The number of 1st instar, pupae and adults are shown, along with the percent emergence of puparia and the percent of offspring that were female. The difference between offspring from uninfected and infected females (when mated to uninfected males) and the difference between offspring from uninfected males and infected males (when mated with infected females) was also assessed via t-tests (on arcsin proportions in the case of proportional data) and are included below.

| Cross | Female | Male | 1st Instar a | Pupae a | Adults a | Percent Emergence of Puparia | Percent of Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uninfected b | Uninfected b | 148.1 ± 29.3 | 136.1 ± 29.1 | 114.5 ± 27.5 | 83.8 ± 5.7 | 56.6 ± 7.6 |

| 2 | Infected | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | |

| 3 | Infected | Uninfected b | 138.8 ± 26.9 | 125.6 ± 24.2 | 103.0 ± 18.3 | 82.4 ± 6.4 | 46.1 ± 3.9 |

| 4 | Infected | 133.5 ± 28.4 | 119.6 ± 27.9 | 102.8 ± 26.5 | 85.8 ± 6.1 | 54.1 ± 4.6 | |

| Statistical comparisons (t-test statistic, df, p value) | |||||||

| 1 versus 3 | 0.573, 10, 0.579 | 0.678, 10, 0.512 | 0.851, 10, 0.414 | 0.399, 10, 0.698 | 2.973, 10, 0.014 | - | |

| 3 versus 4 | 0.333, 10, 0.745 | 0.396, 10, 0.699 | 0.012, 10, 0.990 | 0.920, 10, 0.378 | 3.216, 10, 0.009 | - | |

a Mean ± Standard Deviation; b Antibiotic-treated uninfected strain.

4. Discussion

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the biology of Wolbachia and its application as a tool for the management or modification of insect populations. The distribution of Wolbachia among its dipteran leafminer hosts represents an important first step in developing such applications. This study presents the first broad-scale study to screen natural populations of leaf-mining flies for Wolbachia, mainly focusing on the Agromyzidae from Australia. Our results indicate that Wolbachia is present in 10 agromyzid species (L. sativae, L. huidobrensis, L. trifolii, L. bryoniae, L. chinensis, L. brassicae, L. chenopodii, P. plantaginis, P. syngenesiae and P. praecellens) and two drosophilid species (S. flava and S. australis).

While the Australian specimens we considered were largely adventive species, the specimens of P. praecellens, C. milleri, L. chenopodii and S. australis represent indigenous species. Both groups clearly show a potentially high incidence of Wolbachia infection. More extensive sampling of these species is required to establish the incidence of Wolbachia across the geographic range of these species, since Wolbachia infection frequencies in leafminers and other insects can be quite variable. In Japan, Tagami et al. [48] previously found that 40 L. trifolii individuals were infected out of 226 tested. They detected Wolbachia in only one out of eight field collections and found infections present at different frequencies within laboratory colonies, consistent with our results showing a variable incidence of Wolbachia in this species. Tagami et al. [48] also found that five collections of L. sativae (116 individuals) were uninfected, which contrasts with the fact that we found several infected L. sativae populations. Overall, our field collections suggest that the incidence of Wolbachia across leafminers species and within species is high, with only C. milleri uninfected by Wolbachia, but the L. sativae and L. trifolii results also highlight the potentially high level of polymorphism present in some species.

The phylogenetic tree based on wsp sequences obtained from all agromyzid and drosophilid species analysed indicates seven Wolbachia strains (wLsatA, wLsatB, wLsatD, wLbryA, wLbryB, wLchiA and wLtriA) belonging to Wolbachia subgroup B and two Wolbachia strains (wLhuiA and wLsatC) belonging to Wolbachia subgroup A. Tagami et al. [47,48] detected two strains of Wolbachia in L. trifolii and L. bryoniae (both from Wolbachia B supergroups) and showed that one strain of Wolbachia (wLsatD) induced strong CI in L. trifolii. In our study, wLsatA was the most common strain shared by eight different leaf-mining flies and only one base-pair different from wLsatD based on wsp. MLST analysis indicates that the wLsatA based Wolbachia strain of L. brassicae is a new Wolbachia strain (Lbra_B_1), and the crossing experiments indicate that this strain causes strong CI effect on hosts. Additionally, we note that the sequence of the wsp allele wLsatC (found in P. praecellens and P. syngenesiae) is the same as the Wolbachia wRi strain. This Wolbachia strain was detected in Drosophila simulans in the 1980s in southern California and has been shown to induce strong CI [65].

The presence of Wolbachia in the vast majority of leafminers surveyed here and the fact it is near fixation in many species, suggests that Wolbachia spreads relatively easily in this group through horizontal transmission. Natural Wolbachia infections can spread from low initial frequencies [51]. “Super spreader’’ Wolbachia, aided by reproductive manipulations such as CI, tend to spread readily due to low fitness costs in novel hosts and high maternal transmission rates [51]. In this study, the superinfection (wLsatA and wLsatC) we detected at one site in P. syngenesiae based on the wsp sequencing suggests that phylogenetically distant Wolbachia strains may be readily maintained in the same leaf-mining species. This suggests that at least some species of agromyzids would be ready recipients of Wolbachia infections, increasing the likely success of microinjections. A high rate of natural horizontal transfer of Wolbachia in leafminers may account for the presence of similar Wolbachia strains in unrelated species. Plant-mediated horizontal transmission might explain the high Wolbachia infectious rate within phytophagous leaf-mining species and the presence of identical strains in evolutionarily distant species [66]. All of these findings point to the presence of Wolbachia strains with strong CI and high rates of horizontal transmission in leafminers suitable for future manipulations.

For L. sativae, prior studies have suggested that all members of the L. sativae-A clade (22 specimens tested) were infected with a single Wolbachia subgroup A strain [4], whereas none of the members of the L. sativae-W+L clades (86 specimens tested) had this infection. Parish et al. [67] found no Wolbachia infections in L. sativae (Clade-B) from Brazil (64 specimens tested). However, our study indicates that some populations of the L. sativae-W clade are infected by the Wolbachia subgroup A strain, while others are infected by the subgroup B strain. Moreover, we found that L. sativae (haplotype S.01, Clade-A) from Florida was infected with Wolbachia (NCBI blast tool showed ~93% similar to Wolbachia endosymbiont of Aptinothrips stylifer, GenBank: MT224213) although we excluded this sample due to poor sequence quality. Our Wolbachia screening results are therefore consistent with Scheffer and Lewis [4] in indicating that L. sativae-A clade is infected with Wolbachia. Detection of Wolbachia in other clades may depend on geographical context and perhaps sample size. Parish et al. [67] did not find Wolbachia infections in L. brassicae (12 specimens) (note the CO1 haplotypes of L. brassicae in Brazil are B.02-B.05, while the haplotype from Australia and Timor-Leste is B.01), L. huidobrensis (6 specimens) and Calycomyza malvae (6 specimens). These results contrast with our findings on larger samples of L. brassicae and L. huidobrensis, with all populations of these species that were tested having Wolbachia. Some populations of L. sativae, L. trifolii and L. huidobrensis shared the same wsp allele wLsatA, and it is possible that populations of these species are infected with Wolbachia strain Lbra_B_1 and cause CI.

Selection on Wolbachia tends to operate via the female host to favor strong maternal transmission to the female generation, while a low level of Wolbachia in males could reduce any deleterious fitness effects associated with the Wolbachia infection [68]. Consistent with this prediction and the pattern seen in some Drosophila [68], we found that Wolbachia in L. brassicae differed substantially between the sexes and this may be a consequence of sex-specific selection associated with transmission. It remains to be seen if this sex difference in density is also present in other Liriomyza species. It would be interesting to compare the competitiveness of male flies with natural Wolbachia infections against those sterilized through irradiation.

Following the incursion of L. sativae and L. huidobrensis into Australia, there have been recent detections of L. trifolii in the Torres Strait (QLD, Australia), in Kununurra (WA, Australia) and in the Northern Peninsula Area of Cape York Peninsula in 2021 [10]. It will be worth tracking the Wolbachia status of all these incursions in a range of locations, and to establish patterns of CI across infections from these species to test for the feasibility of an IIT strategy. Tagami et al. [47] raised several challenges that would need to be overcome for an IIT approach against leafminers. In particular, IIT may be too expensive if flies are raised on plants rather than on artificial media, and an efficient sex sorting system would need to be developed. Sultan et al. [69] looked at mechanical sorting of puparia of L. trifolii but this proved difficult, and a genetic sexing method may be required. IIT would likely be restricted to greenhouses initially given costs. IIT may also be more feasible if used against small populations early in the growing season, and if IIT is combined with parasitoids such as Dacnusa sibirica, which is often released early in the growing season overseas to supplement overwintering D. sibirica [70]. In these systems, D. isaea is then released weekly once leafminer numbers build up later in the season [71]. As apparent from experience with SIT, an IIT method will likely need to be combined with other IPM strategies such as parasitoid releases, which represent an effective way of suppressing Liriomyza pests [35,71]. Additionally, the combination of an IIT approach with traditional insecticides seems cost-effective and promising, where insecticides are used to reduce the population to a lower level before using an IIT approach.

Overall, results from this study provide information for understanding Wolbachia infections in different leaf-mining species, as well as patterns of variation within species. Our findings indicate a high incidence of infection within and across species and suggest that transfections across species are likely to have a high chance of success when using other Liriomyza or dipteran species as infection sources. Our results provide a starting point for developing Wolbachia as a future biocontrol agent. Future work could consider further genomic analysis of the Wolbachia strains from different leafminers species, tissue localization of the Wolbachia infection and the generation of transinfections to investigate incompatibility relationships among the Wolbachia from the different leafminers species.

Acknowledgments

We thank Komivi Senyo Akutse, Glenn Bellis, Ching-Chin Chien, Sally Cowan, Fuatino A. Fatiaki, Scott Ferguson, Nhung Le, Wanxue Liu, Jessica Lye, Colby Maeda, Mallik Malipatil, Mani Mua, Levi Odhiamb Ombura, Olivia Reynolds, Shiuh-Feng Shiao, I Wayan Supartha, John Trumble, Lihsin Wu, Kris Wyckhuys and Le Xuan Vi for their help in sourcing international samples for this paper. Qiong Yang, Weibin Jiang, Nancy Endersby-Harshman and Marianne Coquilleau for technical advice and assistance, and Mallik Malipatil for confirmation of morphological identifications.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects12090788/s1, Table S1: Information on leaf-mining fly specimens collected in this study and their Wolbachia infection status. “Number +/− for Wolbachia” indicates fly numbers that were positive/negative to Wolbachia; Figure S1: Estimation of qPCR amplification efficiencies of actin and wsp of Liriomyza brassicae. The original DNA concentration was 1 ng/μL. Standard curves of qPCR used threefold serial dilutions (10 µL of dilution added to 20 µL of H2O) of L. brassicae DNA on three separate occasions under identical conditions; Figure S2: Agarose electrophoresis gel of conventional PCR (actin and wsp) of Liriomyza brassicae. Lanes 1–8: DNA diluted from 3−1 to 3−8 (threefold serial dilutions), Lane 9: negative control (water); Table S2: Specific primers used for quantitative PCR and DNA barcoding of the leafminer species and Wolbachia. For other species, universal primers from Baldo et al. [1] were used; Table S3: Taxonomic information of leaf-mining flies and Wolbachia wsp sequences. Allele names correspond to the taxonomic placement of the host species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X., P.M.R., P.A.U. and A.A.H.; sample collection: X.X., E.P. and P.M.R.; methodology, X.X. and A.G.; software, X.X. and P.A.R.; investigation, X.X.; data curation, X.X., A.G. and P.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, A.A.H., P.M.R., P.A.U., A.G., P.A.R. and E.P.; supervision, A.A.H., P.M.R. and P.A.U.; funding acquisition, A.A.H., P.A.U. and P.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by funding provided by Hort Innovation, using the vegetable and nursery research and development levies, and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Murphy S., LaSalle J. Balancing biological control strategies in the IPM of New World invasive Liriomyza leafminers in field vegetable crops. Biocontrol. News Inf. 1999;20:91N–104N. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weintraub P.G., Scheffer S.J., Visser D., Valladares G., Correa A.S., Shepard B.M., Rauf A., Murphy S.T., Mujica N., MacVean C., et al. The invasive Liriomyza huidobrensis (Diptera: Agromyzidae): Understanding its pest status and management globally. J. Insect Sci. 2017;17:1–27. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iew121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reitz S.R., Gao Y., Lei Z. Insecticide use and the ecology of invasive Liriomyza leafminer management. In: Trdan S., editor. Insecticides—Development of Safer and More Effective Technologies. InTech; Rijeka, Croatia: 2013. pp. 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheffer S.J., Lewis M.L. Mitochondrial phylogeography of vegetable pest Liriomyza sativae (Diptera: Agromyzidae): Divergent clades and invasive populations. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2005;98:181–186. doi: 10.1603/0013-8746(2005)098[0181:MPOVPL]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheffer S.J., Lewis M.L. Mitochondrial phylogeography of the vegetable pest Liriomyza trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae): Diverged clades and invasive populations. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2006;99:991–998. doi: 10.1603/0013-8746(2006)99[991:MPOTVP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Y., Reitz S., Xing Z., Ferguson S., Lei Z. A decade of leafminer invasion in China: Lessons learned. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2017;73:1775–1779. doi: 10.1002/ps.4591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minkenberg O.P.J.M. Dispersal of Liriomyza trifolii. EPPO Bull. 1988;18:173–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2338.1988.tb00362.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X., Coquilleau M.P., Ridland P.M., Umina P.A., Hoffmann A.A. Molecular identification of leafmining flies from Australia including new Liriomyza outbreaks. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021 doi: 10.1093/jee/toab143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liriomyza huidobrensis (Serpentine Leafminer) in New South Wales and Queensland. [(accessed on 30 July 2021)]. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/en/countries/australia/pestreports/2021/07/liriomyza-huidobrensis-in-new-south-wales-and-queensland/

- 10.Liriomyza trifolii (American Serpentine Leafminer) in Queensland and Western Australia. [(accessed on 30 July 2021)]. Available online: https://www.ippc.int/en/countries/australia/pestreports/2021/07/liriomyza-trifolii-american-serpentine-leafminer-in-queensland-and-western-australia/

- 11.Bethke J.A., Parrella M.P. Leaf puncturing, feeding and oviposition behavior of Liriomyza trifolii. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1985;39:149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1985.tb03556.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parrella M.P. Biology of Liriomyza. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1987;32:201–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.32.010187.001221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matteoni J., Broadbent A. Wounds caused by Liriomyza trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae) as sites for infection of chrysanthemum by Pseudomonas cichorii. Can. J. Plant. Pathol. 1988;10:47–52. doi: 10.1080/07060668809501763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deadman M., Khan I., Thacker J., Al-Habsi K. Interactions between leafminer damage and leaf necrosis caused by Alternaria alternata on potato in the Sultanate of Oman. Plant. Pathol. J. 2002;18:210–215. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.2002.18.4.210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zitter T., Tsai J. Transmission of three potyviruses by the leafminer Liriomyza sativae (Diptera: Agromyzidae) Plant. Dis. Rep. 1977;61:1025–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson M., Welter S., Toscano N., Ting P., Trumble J. Reduction of tomato leaflet photosynthesis rates by mining activity of Liriomyza sativae (Diptera: Agromyzidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 1983;76:1061–1063. doi: 10.1093/jee/76.5.1061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hidrayani, Purnomo, Rauf A., Ridland P.M., Hoffmann A.A. Pesticide applications on Java potato fields are ineffective in controlling leafminers, and have antagonistic effects on natural enemies of leafminers. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 2005;51:181–187. doi: 10.1080/09670870500189044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trumble J.T., Toscano N.C. Impact of methamidophos and methomyl on populations of Liriomyza species (Diptera: Agromyzidae) and associated parasites in celery. Can. Entomol. 1983;115:1415–1420. doi: 10.4039/Ent1151415-10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parrella M.P., Keil C.B. Insect pest management: The lesson of Liriomyza. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1984;30:22–25. doi: 10.1093/besa/30.2.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leibee G.L., Capinera J.L. Pesticide resistance in Florida insects limits management options. Fla. Entomol. 1995;78:386–399. doi: 10.2307/3495525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson J.S. Development and stability of insecticide resistance in the leafminer Liriomyza trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae) to cyromazine, abamectin, and spinosad. J. Econ. Entomol. 2004;97:112–119. doi: 10.1093/jee/97.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mujica N., Kroschel J. Leafminer fly (Diptera: Agromyzidae) occurrence, distribution, and parasitoid associations in field and vegetable crops along the Peruvian coast. Environ. Entomol. 2011;40:217–230. doi: 10.1603/EN10170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Askari-Saryazdi G., Hejazi M.J., Ferguson J.S., Rashidi M.-R. Selection for chlorpyrifos resistance in Liriomyza sativae Blanchard: Cross-resistance patterns, stability and biochemical mechanisms. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2015;124:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weintraub P.G., Horowitz A.R. Effects of translaminar versus conventional insecticides on Liriomyza huidobrensis (Diptera: Agromyzidae) and Diglyphus isaea (Hymenoptera Eulophidae) populations in celery. J. Econ. Entomol. 1998;91:1180–1185. doi: 10.1093/jee/91.5.1180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leibee G. Toxicity of abamectin to Liriomyza trifolii (Burgess) (Diptera: Agromyzidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 1988;81:738–740. doi: 10.1093/jee/81.2.738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Lenteren J.C., Bolckmans K., Köhl J., Ravensberg W.J., Urbaneja A. Biological control using invertebrates and microorganisms: Plenty of new opportunities. BioControl. 2018;63:39–59. doi: 10.1007/s10526-017-9801-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lacey L.A., Frutos R., Kaya H.K., Vail P. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: Do they have a future? Biol. Control. 2001;21:230–248. doi: 10.1006/bcon.2001.0938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smart G., Jr. Entomopathogenic nematodes for the biological control of insects. J. Nematol. 1995;27:529–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Lenteren J.C. The state of commercial augmentative biological control: Plenty of natural enemies, but a frustrating lack of uptake. BioControl. 2012;57:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10526-011-9395-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chow A., Heinz K.M. Biological control of leafminers on ornamental crops. In: Heinz K.M., Van Driesche R.G., Parrella M.P., editors. Biocontrol in Protected Culture. Ball Publishing; Batavia, IL, USA: 2004. pp. 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuijderwijk M., van den Hoek C., Mostert J. Creating crop solutions in chrysanthemums by using the combined strengths of beneficials and chemicals. IOBC WPRS Bull. 2008;32:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heimpel G.E., Lundgren J.G. Sex ratios of commercially reared biological control agents. Biol. Control. 2000;19:77–93. doi: 10.1006/bcon.2000.0849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chow A., Heinz K. Control of Liriomyza langei on chrysanthemum by Diglyphus isaea produced with a standard or modified parasitoid rearing technique. J. Appl. Entomol. 2006;130:113–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2005.01028.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chow A., Heinz K.M. Using hosts of mixed sizes to reduce male-biased sex ratio in the parasitoid wasp, Diglyphus isaea. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2005;117:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2005.00350.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaspi R., Parrella M.P. Improving the biological control of leafminers (Diptera: Agromyzidae) using the sterile insect technique. J. Econ. Entomol. 2006;99:1168–1175. doi: 10.1093/jee/99.4.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mateos M., Martinez Montoya H., Lanzavecchia S.B., Conte C., Guillén K., Morán-Aceves B.M., Tsiamis G. Wolbachia pipientis associated with tephritid fruit fly pests: From basic research to applications. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1080. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Werren J.H., Baldo L., Clark M.E. Wolbachia: Master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:741–751. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Neill S.L., Hoffmann A.A., Werren J.H. Influential Passengers: Inherited Microorganisms and Arthropod Reproduction. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffmann A.A., Turelli M. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. In: O’Neill S., Hoffmann A., Werren J., editors. Influential Passengers: Microorganisms and Invertebrate Reproduction. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1997. pp. 42–80. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engelstädter J., Telschow A. Cytoplasmic incompatibility and host population structure. Heredity. 2009;103:196–207. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connor L., Plichart C., Sang A.C., Brelsfoard C.L., Bossin H.C., Dobson S.L. Open release of male mosquitoes infected with a Wolbachia biopesticide: Field performance and infection containment. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6:e1797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atyame C.M., Pasteur N., Dumas E., Tortosa P., Tantely M.L., Pocquet N., Licciardi S., Bheecarry A., Zumbo B., Weill M., et al. Cytoplasmic incompatibility as a means of controlling Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus mosquito in the islands of the south-western Indian Ocean. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011;5:e1440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng X., Zhang D., Li Y., Yang C., Wu Y., Liang X., Liang Y., Pan X., Hu L., Sun Q., et al. Incompatible and sterile insect techniques combined eliminate mosquitoes. Nature. 2019;572:56–61. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kittayapong P., Ninphanomchai S., Limohpasmanee W., Chansang C., Chansang U., Mongkalangoon P. Combined sterile insect technique and incompatible insect technique: The first proof-of-concept to suppress Aedes aegypti vector populations in semi-rural settings in Thailand. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019;13:e0007771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zabalou S., Riegler M., Theodorakopoulou M., Stauffer C., Savakis C., Bourtzis K. Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a means for insect pest population control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15042–15045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403853101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pagendam D.E., Trewin B.J., Snoad N., Ritchie S.A., Hoffmann A.A., Staunton K.M., Paton C., Beebe N. Modelling the Wolbachia incompatible insect technique: Strategies for effective mosquito population elimination. BMC Biol. 2020;18:161. doi: 10.1186/s12915-020-00887-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tagami Y., Doi M., Sugiyama K., Tatara A., Saito T. Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in Liriomyza trifolii and its possible use as a tool in insect pest control. Biol. Control. 2006;38:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2006.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tagami Y., Doi M., Sugiyama K., Tatara A., Saito T. Survey of leafminers and their parasitoids to find endosymbionts for improvement of biological control. Biol. Control. 2006;38:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2006.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaiser W., Huguet E., Casas J., Commin C., Giron D. Plant green-island phenotype induced by leaf-miners is mediated by bacterial symbionts. Proc. Royal Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010;277:2311–2319. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coquilleau M.P., Xu X., Ridland P.M., Umina P.A., Hoffmann A.A. Variation in sex ratio of the leafminer Phytomyza plantaginis Goureau (Diptera: Agromyzidae) from Australia. Austral Entomol. 2021;60:610–620. doi: 10.1111/aen.12557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turelli M., Cooper B.S., Richardson K.M., Ginsberg P.S., Peckenpaugh B., Antelope C.X., Kim K.J., May M.R., Abrieux A., Wilson D.A., et al. Rapid global spread of wRi-like Wolbachia across multiple Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:963–971. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baldo L., Dunning Hotopp J.C., Jolley K.A., Bordenstein S.R., Biber S.A., Choudhury R.R., Hayashi C., Maiden M.C., Tettelin H., Werren J.H. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:7098–7110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00731-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou W., Rousset F., O’Neill S. Phylogeny and PCR–based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1998;265:509–515. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lo N., Paraskevopoulos C., Bourtzis K., O’Neill S.L., Werren J., Bordenstein S., Bandi C. Taxonomic status of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia pipientis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. 2007;57:654–657. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang Y.-W., Chen J.-Y., Lu M.-X., Gao Y., Tian Z.-H., Gong W.-R., Zhu W., Du Y.-Z. Selection and validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis under different experimental conditions in the leafminer Liriomyza trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae) PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0181862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang L.H., Kang L. Cloning and interspecific altered expression of heat shock protein genes in two leafminer species in response to thermal stress. Insect Mol. Biol. 2007;16:491–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee S.F., White V.L., Weeks A.R., Hoffmann A.A., Endersby N.M. High-throughput PCR assays to monitor Wolbachia infection in the dengue mosquito (Aedes aegypti) and Drosophila simulans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:4740–4743. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00069-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beri S.K. Biology of a leaf miner Liriomyza brassicae (Riley) (Diptera: Agromyzidae) J. Nat. Hist. 1974;8:143–151. doi: 10.1080/00222937400770101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., Stones-Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S., Buxton S., Cooper A., Markowitz S., Duran C., et al. Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rozas J., Ferrer-Mata A., Sánchez-DelBarrio J.C., Guirao-Rico S., Librado P., Ramos-Onsins S.E., Sánchez-Gracia A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34:3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen L.-T., Schmidt H.A., Von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoffmann A.A., Turelli M., Simmons G.M. Unidirectional incompatibility between populations of Drosophila simulans. Evolution. 1986;40:692–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1986.tb00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li S.-J., Ahmed M.Z., Lv N., Shi P.-Q., Wang X.-M., Huang J.-L., Qiu B.-L. Plant-mediated horizontal transmission of Wolbachia between whiteflies. ISME J. 2017;11:1019–1028. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parish J.B., Carvalho G.A., Ramos R.S., Queiroz E.A., Picanço M.C., Guedes R.N., Corrêa A.S. Host range and genetic strains of leafminer flies (Diptera: Agromyzidae) in eastern Brazil reveal a new divergent clade of Liriomyza sativae. Agric. For. Entomol. 2017;19:235–244. doi: 10.1111/afe.12202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richardson K.M., Griffin P.C., Lee S.F., Ross P.A., Endersby-Harshman N.M., Schiffer M., Hoffmann A.A. A Wolbachia infection from Drosophila that causes cytoplasmic incompatibility despite low prevalence and densities in males. Heredity. 2019;122:428–440. doi: 10.1038/s41437-018-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sultan M., Buitenhuis R., Murphy G., Scott-Dupree C.D. Development of a mechanical sexing system to improve the efficacy of an area-wide sterile insect release programme to control American serpentine leafminer (Diptera: Agromyzidae) in Canadian ornamental greenhouses. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2017;73:830–837. doi: 10.1002/ps.4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Minkenberg O.P. Reproduction of Dacnusa sibirica (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), an endoparasitoid of leafminer Liriomyza bryoniae (Diptera: Agromyzidae) on tomatoes, at constant temperatures. Environ. Entomol. 1990;19:625–629. doi: 10.1093/ee/19.3.625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walker C. Ph.D. Thesis. Imperial College London; London, UK: 2013. The Application of Sterile Insect Technique against the Tomato Leafminer Liriomyza bryoniae. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.