Abstract

Pancreatic carcinoma (PC) is greatly induced by the KRAS gene mutation, but effective targeted delivery for gene therapy has not existed. Small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) serves as an advanced therapeutic modality and holds great promise for cancer treatment. However, the development of a non-toxic and high-efficiency carrier system to accurately deliver siRNA into cells for siRNA-targeted gene silencing is still a prodigious challenge. Herein, polyethylenimine (PEI)-modified hydroxyapatite (HAp) nanoparticles (HAp-PEI) were fabricated. The siRNA of the KRAS gene (siKras) was loaded onto the surface of HAp-PEI via electrostatic interaction between siRNA and PEI to design the functionalized HAp-PEI nanoparticle (HAp-PEI/siKras). The HAp-PEI/siKras was internalized into the human PC cells PANC-1 to achieve the maximum transfection efficiency for active tumor targeting. HAp-PEI/siKras effectively knocked down the expression of the KRAS gene and downregulated the expression of the Kras protein in vitro. Furthermore, the treatment with HAp-PEI/siKras resulted in greater anti-PC cells’ (PANC-1, BXPC-3, and CFPAC-1) efficacy in vitro. Additionally, the HAp-PEI exhibited no obvious in vitro cytotoxicity in normal pancreatic HPDE6-C7 cells. These findings provided a promising alternative for the therapeutic route of siRNA-targeted gene engineering for anti-pancreatic cancer therapy.

Keywords: hydroxyapatite, siRNA delivery, pancreatic cancer cells, KRAS gene, gene silence, anticancer

1. Introduction

Pancreatic carcinoma (PC) is the most severe type of human melanoma that caused secondary neural microenvironment and has the highest mortality among all diagnosed tumors [1,2,3]. The available treatments such as chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy can only enhance 5.0–70 months, and a 5-year survival rate is about 4% in PC patients [4,5,6]. Even for some patients diagnosed at early stages and who received intensive treatment the 5-year survival rate is lower than 20% [7,8]. Additionally, the mortality rate (48,220) of PC patients is nearly close to the rate of incidence (60,430) due to the absence of effective treatment. Therefore, advanced therapy is essential in uncovering the disease in its infancy [9]. Further, several factors are involved in PC induction and progression, and among them KRAS proto-oncogene activation mutation is the most crucial in diagnosed patients [10]. Almost 95% of cases of PC have point mutation at G12, G13, and Q61 codons in the KRAS activation domain as a result of the mutant Kras protein generation, which provokes growth and proliferation of pancreatic tumors [11,12]. However, KRAS-based targeting is a challenging assignment. Thus, improvement in PC diagnosis, treatment, and prevention requires interdisciplinary cooperation and novel trial designs [13].

Recently, RNA interference is considered a promising therapeutic alternative in the treatment of PC. It is the most sophisticated post-transcriptional gene silencing therapy by small interfering double-stranded RNA (siRNA) that can induce sequence-specific silencing of about 80% of the targeted protein’s mRNA to effectively inhibit tumor cell proliferation [14,15,16,17]. Further, it is an emerging genetic technique that deals with several kinds of human melanomas. For instance, in KRAS-dependent mutant cancer, dual knockout of RhoA/Rho kinase (ROCK) and polp-like kinase-1 by siRNA enhanced the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase, which ultimately impaired the growth of KRAS-mutant cells’ proliferation [18]. Guan et al. [19] successfully induced apoptosis of PC2 PC cell lines by inhibiting the expression of the apoptosis-related gene Survivin using RNA interference technology. However, siRNA is a hydrophilic biological macromolecule with a molecular weight of about 1.3 × 104, along with a large size and high negative surface charge, which makes it difficult to cross the same electronegative cell membrane [20]. Meanwhile, free siRNA cannot escape from the extensive cell nuclei in the bloodstream and active renal clearance, which makes it almost impossible for exogenous free siRNA existence to conduct RNA interference independently [21,22]. Therefore, the development of a low-toxicity and high-efficiency carrier system that accurately delivers siRNA into the cells is still a huge challenge for siRNA-based targeted gene silencing.

Nano-hydroxyapatite (nHAp), a naturally occurring calcium and phosphorus-based inorganic material, is currently widely used for biomedical applications [23]. nHAp showed appealing possibilities in tissue engineering due to its unique physio-chemical features. A study was reported regarding the suitability of Fe/Sr co-substituted HAp nanoparticles for tissue engineering. These nanoparticles were appropriated for human mesenchymal cells and demonstrated high blood compatibility, enhanced drug release capability, and an improved tissue-repair profile [24]. The previous study reported that a HAp-laminin composite showed the optimal neural stem cells (NSCs) adhesion and well-spread cell morphology, and also supported NSCs proliferation without causing any cytotoxicity, which is promising for neural-related applications [25]. Additionally, nHAp has aroused extensive interest in drug delivery research due to its high biocompatibility, low cytotoxicity, better biodegradability, and favorable affinity to plenty of molecules such as chemotherapy drugs, pDNA, and siRNA. In particular, it gained remarkable potential as a gene delivery system in tumor treatment and therapy [26]. Gu et al. [27] reported that the NR2B siRNA-loaded HAp nanoparticle could not only eliminate the formalin-induced tetanic response but also significantly downregulate the expression of NR2B protein in mice. However, nHAp has weak positive surface charges that lead to a feeble loading and low transfection ability of siRNA [28]. Therefore, modification in surface charges is crucial for siRNA-targeted gene silencing, which can be achieved by developing a simple and effective modification strategy.

Earlier reports were concordant with KRAS activation mutation and highly significantly associated with the development of metastasis pancreatic carcinoma [29]. Recently, a siRNA-mediated knockout mechanism was implicated in the regulation of protein overexpression [30]. Therefore, KRAS silencing-based siRNA might provide a promising option for the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

In this study, HAp nanoparticles were prepared by a chemical precipitation method and modified by polyethyleneimine (PEI), a commonly used cationic polymer. PEI-modified HAp nanoparticles (HAp-PEI) were used as the carrier of KRAS siRNA. The loading and transfection ability of siRNA was examined by agarose gel electrophoresis and observed by confocal microscope, respectively. The biocompatibility, as well as the effect of pancreatic cancer-related gene silencing and cancer-cell inhibition after carrying siRNA were also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ca(NO3)2, Na2HPO4, NaOH, polyethylene glycol-400 (PEG-400) and polyethyleneimine (PEI, M.W. 70,000) were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). We purchased 3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), Trypsin-EDTA solution, LysotrackerTM Red and the QuantiChromTM calcium ion detection kit from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). High glucose Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) and Roswell park memorial institute-1640 (RPMI-1640) were obtained from BioInd (Beit-Haemek, Israel). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gibco (Sidney, Australia). Fluorescently labeled siRNA-FAM, negative control siRNA (siNC, sense strand, 5′-UUC UCC GAA CGU GUC ACG UTT-3′), KRAS siRNA (siKras, sense strand, 5′-CAC CAU UAU AGA GAA CAA ATT-3′), and commercial transfection reagent siRNA-Mate were obtained from Genpharm (Shanghai, China). Other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

Human pancreatic cancer cells PANC-1, BXPC-3, CFPAC-1, and human pancreatic ductal epithelial cell HPDE6-C7 were purchased from the cell bank of Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). PANC-1 and CFPAC-1 were grown in high glucose DMEM, and HPDE6-C7 were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium. Cells were incubated with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of HAp and HAp-PEI

HAp nanoparticles were synthesized as following: 10 mL 3.74 mmol/L (NH4)2HPO4 aqueous solutions were added dropwise to 10 mL 6.25 mmol/L Ca(NO3)2, and the pH was adjusted to 10~13 by adding ammonia solution. After incubation for 30 min, 100 μL dispersant PEG-400 was added to the suspension and incubated for another 3 h. The nanoparticle suspension was centrifuged (8000 rpm × 3 min), and HAp precipitate was collected.

Then, 100 μL of 10 mg/mL PEI was added to the HAp suspension to synthesize HAp-PEI nanoparticles. After 3 h, the mixture was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 3 min to remove the residual PEI and obtained HAp-PEI precipitate.

The morphology, structure, and chemical composition of HAp and HAp-PEI were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM), dynamic light scattering (DLS), X-ray diffraction measurement (XRD), fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy, thermogravimetry (TG), and Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS).

2.3. In Vitro Degradation of HAp-PEI

The 90 mg of HAp-PEI was incubated in 10 mL of PBS (pH value of 5.6, 6.5 and 7.4) under gentle shaking at 37 °C for various times up to 90 days. The pH value of 5.6, 6.5 and 7.4 was used to simulate human cell lysosome, tumor and normal fluid microenvironment, respectively. At specific time points, the supernatant was withdrawn by centrifugation and replaced by the same volume of fresh PBS. The concentration of Ca2+ in the clear supernatant was detected by the QuantiChromTM calcium ion detection kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All the tests were carried out in triplicate, and the average values were shown in the form of tables and graphs.

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of HAp-PEI and HAp was evaluated by MTT assay. Human pancreatic cancer cell PANC-1, BXPC-3, CFPAC-1 and human pancreatic ductal epithelial cell HPDE6-C7 were seeded in 96-well plates (San Diego, BD American) at a density of 5000 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. HAp-PEI and HAp of various concentrations were added in medium and incubated for another 48 h. Then, 10 μL of MTT (5 mg/mL in pH 7.4 PBS) was added in the medium and incubated for 4-h, after which the medium was replaced with 150 μL DMSO to solubilize the formazan crystals. The UV absorbance intensity of cells, which can be converted to the number of viable cells, was measured by Microplate Reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland) at λ = 490 nm.

2.5. siRNA Loading and Transfection

2.5.1. siRNA Loading

The complexes of HAp-PEI/siRNA were formed by incubating siRNAs with HAp-PEI at room temperature for 20 min after gentle mixing for 10 times. The loading efficiency of siRNA to HAp-PEI was evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The 2 μg of siRNA negative control (siNC) was added into 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 μg of HAp-PEI suspension in DEPC H2O, respectively (Table 1). Afterwards, the supernatant was loaded into the wells of 1% agarose gel. The images were acquired using a gene genius bioimaging system.

Table 1.

Amounts of HAp-PEI and siRNA with the different weight ratios.

| Groups | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAp-PEI/siRNA (w/w) | / | 1/1 | 2/1 | 4/1 | 6/1 | 8/1 | 10/1 | 12/1 |

| HAp-PEI (μg) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 |

| siRNA (μg) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

2.5.2. siRNA-FAM Transfection

PANC-1 cells were seeded on a cell petri dish at a concentration of 2 × 104 cells/well in 2 mL medium and then incubated overnight. Then, siRNA-FAM (green fluorescence), siRNA-Mate/siRNA-FAM and HAp-PEI/siRNA-FAM (the weight ratio of HAp-PEI and siRNA is 8/1) in DEPC H2O were added to the cells and incubated for 8 h by keeping 5 μL siRNA-FAM in each group. siRNA-Mate was utilized as a commercial siRNA transfection reagent that served as a positive control compared with the HAp-PEI carrier. Further, the inversed fluorescent microscope (IFM) (Olympus, Japan) was used to confirm intracellular uptake, and lysosomes staining of LysotrackerTM Red (red fluorescence) was employed to locate siRNA-FAM. Briefly, after siRNA transfection for a predetermined time, cells were washed 3 times with PBS followed by the addition of 50 nM LysotrackerTM Red (lysosomes maker). After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, the cells were washed 3 times with PBS and then observed under a fluorescent microscope, with excitation and emission of green (Ex/Em 494/530 nm for siRNA-FAM) and red (Ex/Em 577/590 nm for LysotrackerTM Red) fluorescence.

2.5.3. KRAS siRNA Transfection

Pancreatic cancer cells (PANC-1 and CFPAC-1) were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and incubated overnight. The cells were treated with HAp-PEI/siKras in the culture medium while other wells were treated with DEPC H2O, free siKras, HAp-PEI, HAp/siKras, siRNA-Mate/siKras at equivalent siRNA concentration for 48 h, respectively. The cellular levels of Kras mRNA and protein were assessed using RT-qPCR and Western blot, respectively.

2.6. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Pancreatic cancer cells (PANC-1 and CFPAC-1) were collected, and total RNA from transfected cells was isolated using a total RNA extraction reagent (Genpharm, Shanghai, China). The relative expression of Kras mRNA was detected by a custom gene RT-qPCR quantitation kit (Shanghai, China). The sense primer sequence of KRAS gene was 5′-AAC TTG TGG TAG TTG GAG C-3′, and the antisense primer sequence was 5′-GGA TCA TAT TCG TCC ACA AAA TG-3′. Similarly, the sense primer sequence of GAPDH was 5′-CAT GAG AAG TAT GAC AAC AGC CT-3′, and the antisense primer sequence was 5′-AGT CCT TCC ACG ATA CCA AAG T-3′. The standard curves were generated, and relative gene expression of KRAS was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method using GAPDH as the reference gene.

2.7. Western Blot

The transfected PANC-1 and CFPAC-1 cells were washed twice with PBS and then were lysed by 60 μL of lysis buffer with 1 mmol/L phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride for 30 min on ice. Total protein was acquired after centrifuging at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min, and the concentration of protein was determined by BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The total soluble protein was separated on SDS-PAGE and then transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane. After incubation in primary mouse anti-Kras antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at 1:1000 dilutions and secondary antibody HRP-labeled Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) at 1:500 dilutions in succession, the specific blot was visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Tanon5500, Shanghai, China).

2.8. In Vitro Anti-Pancreatic Tumor Cell Assay

The viability of HAp-PEI/siKras treated pancreatic cancer cells (PANC-1, CFPAC-1 and BXPC-3) was evaluated by MTT assay as described. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5000 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. The cells were treated with HAp-PEI/siKras, DEPC H2O, free siKras, HAp-PEI, HAp/siKras, siRNA-Mate/siKras, and HAp-PEI/siNC at equivalent siRNA concentrations, respectively, for 72 h and then their viabilities were evaluated.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was determined using Student’s paired t-test, and the value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All presented data were as the mean ± SD.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of HAp-PEI

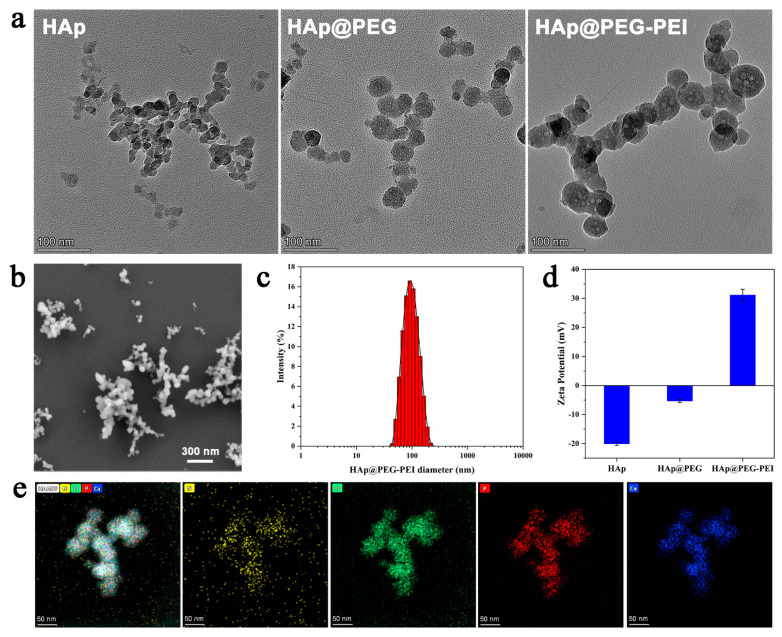

HAp-PEI nanoparticles were synthesized with the regulation of PEG and then modified by PEI. Structural characterizations were observed by TEM (Figure 1a) and FE-SEM (Figure 1b), and results showed that pure HAp, HAp with PEG regulation (HAp@PEG) and then PEI-modified NPs (HAp@PEG-PEI) are all in spherical shape. TEM images showed HAp nanoparticles with homogeneous size, and the dispersion of the particles was obviously improved after PEG treatment. HAp@PEG and HAp@PEG-PEI NPs revealed a more uniform and slightly larger size as compared with pure HAp. DLS measurements (Figure 1c) indicated a narrow, monomodal particle distribution with an intensity average hydrodynamic diameter of about 95.76 nm (PDI 0.198) for the HAp@PEG-PEI sample. Moreover, the zeta-potential (Figure 1d) of the prepared PEG-coated HAp NPs changed from −20.03 ± 0.55 mV to −5.30 ± 0.57 mV, and a significant increase was found in the HAp@PEG-PEI sample, indicating that the PEI modification has an obvious effect on the surface of NPs by electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged HAp@PEG NPs and positively charged PEI, which can be beneficial to deliver siRNA with high negative surface charge into the cells for siRNA-based targeted gene silencing. To examine elemental confirmation of the prepared HAp@PEG-PEI NPs, STEM element analysis was achieved and the results are depicted in Figure 1e. The corresponding element mapping analysis clearly endorses the construction of NPs mainly composed of N (yellow), O (green), P (red) and Ca (blue), which further confirms the successful PEI-modification on HAp NPs.

Figure 1.

(a) TEM images of HAp, HAp@PEG and HAp@PEG-PEI, (b) SEM image, (c) hydrodynamic size distributions, (d) zeta potential, and (e) TEM elemental color mapping of HAp@PEG-PEI. Elements: N (yellow), O (green), P (red) and Ca (blue).

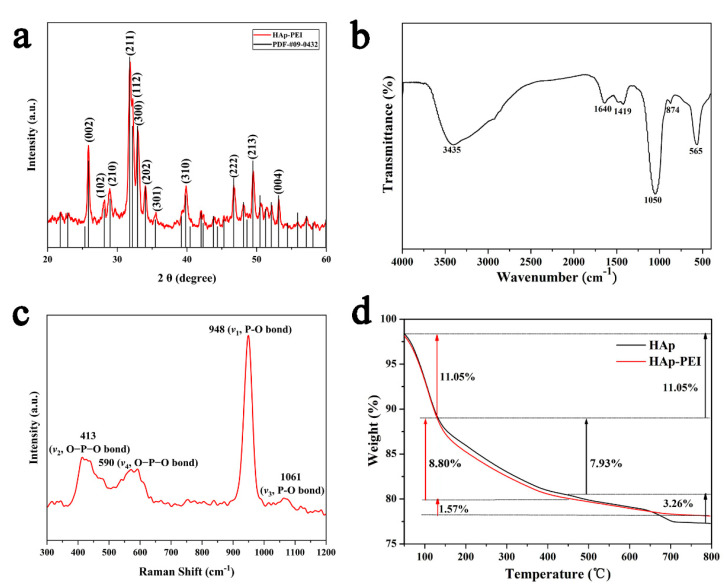

Furthermore, the XRD technique was used to observe the crystal phase and for purity identification of the prepared HAp-PEI NPs. Figure 2a shows the crystal patterns of HAp-PEI. The diffraction spectra of the prepared calcium phosphate are well matched with the XRD standard card of hydroxyapatite (JCPDS#09-0432), and the sharp diffraction peaks indicate the good crystallinity and the hydroxyapatite phase purity. Further, the average crystalline size of HAp-PEI NPs was calculated by the Scherrer equation to be about 36.1 nm. The lattice parameters of HAp-PEI NPs were calculated and the obtained values were a = b = 9.421, c = 6.896 Å, which are consistent with the standard values. In addition, the functional groups in HAp-PEI were characterized by FTIR spectra (Figure 2b). The intense absorption band located at 1050 cm−1 is ascribed to the stretching vibration (ν3) of the phosphate (PO43−) groups, and the absorption band located at 565 cm−1 is attributed to the bending vibration (ν4) of the PO43− groups [31,32]. The absorption bands located at 3445 cm−1 and 1640 cm−1 are attributed to the hydroxyl group and adsorbed water, respectively. Moreover, the appearance of CO32− absorption peaks at 874 cm−1 (ν2) and 1419 cm−1 (ν3) indicates the obtained HAp-PEI is a typical carbonated calcium phosphate [33,34]. Moreover, the HAp-PEI NPs were investigated by Raman spectroscopy. The Raman spectrum (Figure 2c) of HAp-PEI has a characteristic very strong PO43− peak at 948 cm−1 (ν1, P-O bond), which corresponds to a totally symmetric stretching mode of the tetrahedral. Apart from this peak, 413 cm−1 (ν2, O-P-O bond), 590 cm−1 (ν4, O-P-O bond), and 1061 cm−1 (ν1, P-O bond) peaks were also resolved. All bands are assigned to internal vibrational modes of the PO43− groups [35]. The Raman spectrum confirms the XRD pattern and FTIR spectra. The mass loss curve of the HAp-PEI was further carried out by TG analysis, and the curve is roughly divided into three steps (Figure 2d). For HAp and HAp-PEI, the weight loss of 11.05% in the heating process from 20 °C to 130 °C is due to the volatilization of adsorbed water. The weight loss of 7.93% in HAp at 130–450 °C corresponds to the decomposition of the PEG. The weight loss of 8.80% in HAp-PEI is indicating that the polymer content (PEG and PEI) in HAp-PEI is around 8.80%. The difference between HAp and HAp-PEI is about 0.87%, which may be due to the modification of HAp by PEI. The mass loss resulting from further heating represents the decomposition of the hydroxyapatite itself.

Figure 2.

(a) XRD pattern, (b) FTIR and (c) Raman spectra of HAp-PEI, and (d) TG curves of HAp and HAp-PEI.

3.2. In Vitro Degradation of HAp-PEI

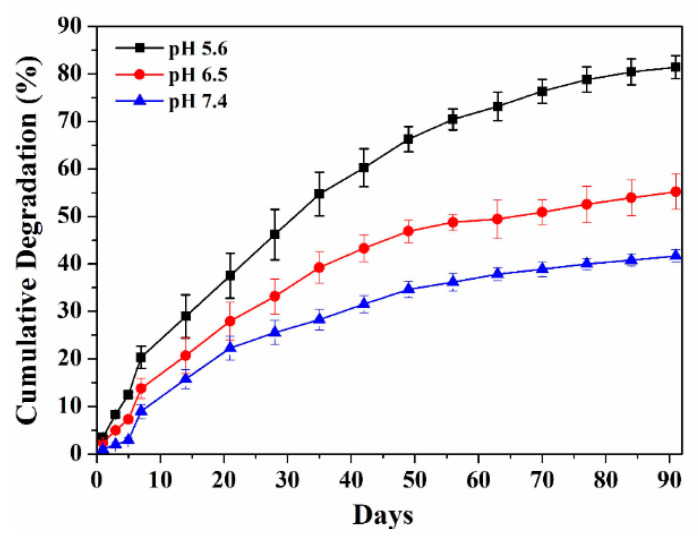

In vitro degradation of HAp-PEI was performed by immersing in PBS with various pH values of 5.6, 6.5, and 7.4 under gentle shaking at 37 °C for 90 days. The particles need to be degraded quickly after going inside the lysosomes (pH 5.6) to release the siRNA and activate the siRNA-based gene silencing in cancer cells. Therefore, in vitro degradation behavior of HAp-PEI in PBS with pH values of 5.6 was performed. The degradation behavior under pH 6.5 and 7.4 was additionally investigated to confirm the pH-dependent biodegradability of HAp. The degradation behavior for 90 days was to check the long-term behavior of the prepared NPs. As shown in Figure 3, the in vitro degradation behavior of HAp-PEI exhibited a similar trend at different pH values.

Figure 3.

In vitro degradation profiles of HAp-PEI in PBS with various pH values of 5.6, 6.5 and 7.4 at 37 °C.

After a 90-day degradation profile, the cumulative degradation amount of HAp-PEI in PBS with pH of 5.6, 6.5, and 7.4 reached about 80%, 50%, and 40%, respectively. It is obvious that the degradation rate of HAp-PEI increases significantly with a decrease in pH from 7.4 to 5.6, indicating a sustained and pH-responsive degradation behavior. Therefore, the HAp-PEI nanoparticles possess excellent in vitro degradation ability and could be a promising siRNA carrier for siRNA-targeted gene silencing applications.

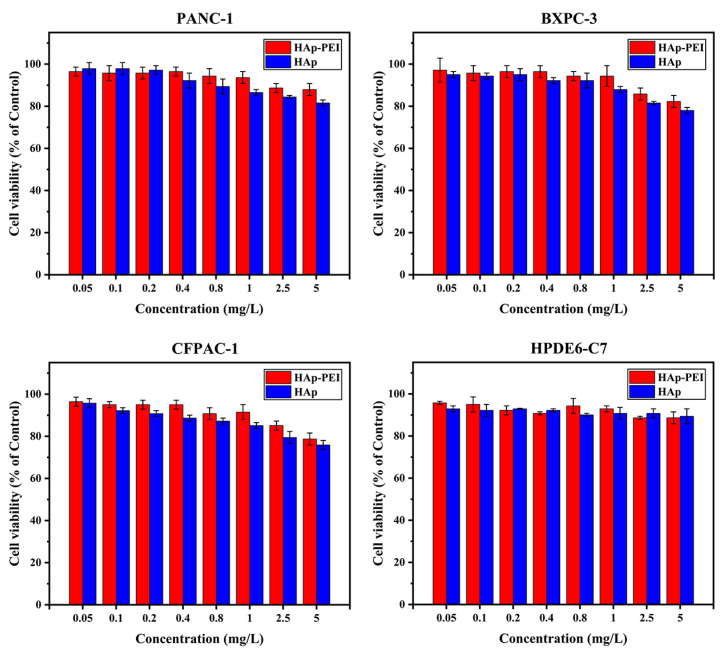

3.3. In Vitro Biocompatibility of HAp-PEI

Further, in vitro biocompatibility of HAp and HAp-PEI was investigated by MTT assay. The cytotoxicity in human PC cells (PANC-1, BXPC-3, and CFPAC-1) and human pancreatic ductal epithelial cell HPDE6-C7 was evaluated. As shown in Figure 4, MTT assay of cells with various concentrations (0.05 mg/L–5 mg/L) of HAp and HAp-PEI treatment revealed that cell viability compared with control was over 80%, indicating that the HAp and HAp-PEI demonstrate good biocompatibility on both human PC and normal cells, which lays the foundation for its use as an anticancer gene carrier.

Figure 4.

Cell viability of pancreatic cancer cells (PANC-1, BXPC-3, CFPAC-1) and pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (HPDE6-C7) co-incubated with HAp-PEI and HAp at various concentrations (0.05 mg/L–5 mg/L) for 48 h.

3.4. siRNA Loading Capability

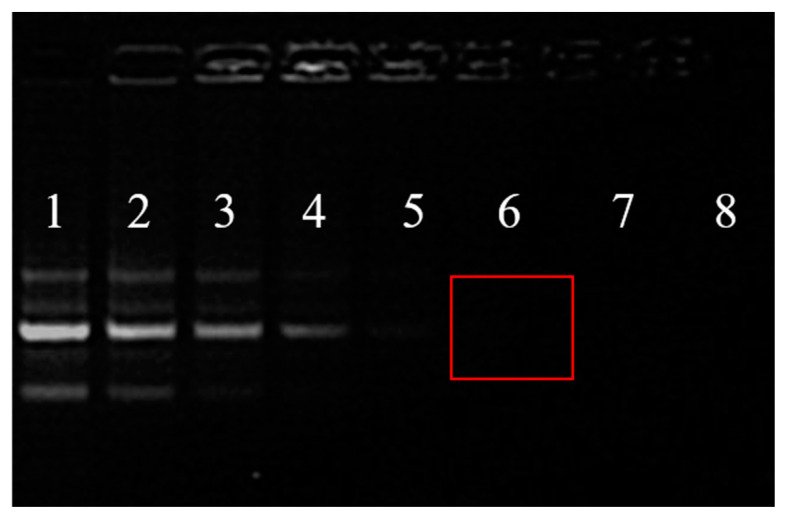

The agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to investigate the siRNA loading capability of HAp-PEI. As shown in Figure 5, with the increment in HAp-PEI concentration, siRNA bands are significantly shallow, and the siRNA band has disappeared when the mass of HAp-PEI is up to 16 μg (group 6, red rectangular marked), which represents that siRNA had been completely adsorbed by HAp-PEI. Thus, the siRNA could be loaded efficiently by HAp-PEI, and the best weight ratio of HAp-PEI and siRNA for loading was 8/1.

Figure 5.

Agarose gel electrophoresis map of siRNA in different groups of siRNA loading. The mass of siRNA was 2 μg, and HAp-PEI were 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 μg, respectively, in 1 to 8 groups. The weight ratios of HAp-PEI and siRNA (HAp-PEI/siRNA) were 0, 1/1, 2/1, 4/1, 6/1, 8/1, 10/1, and 12/1, respectively, in 1 to 8 groups. Group 1–5: siRNA bands are gradually shallow; Red rectangular marked group 6: HAp-PEI/siRNA (w/w) = 8/1, siRNA band has disappeared.

3.5. In Vitro Transfection of siRNA

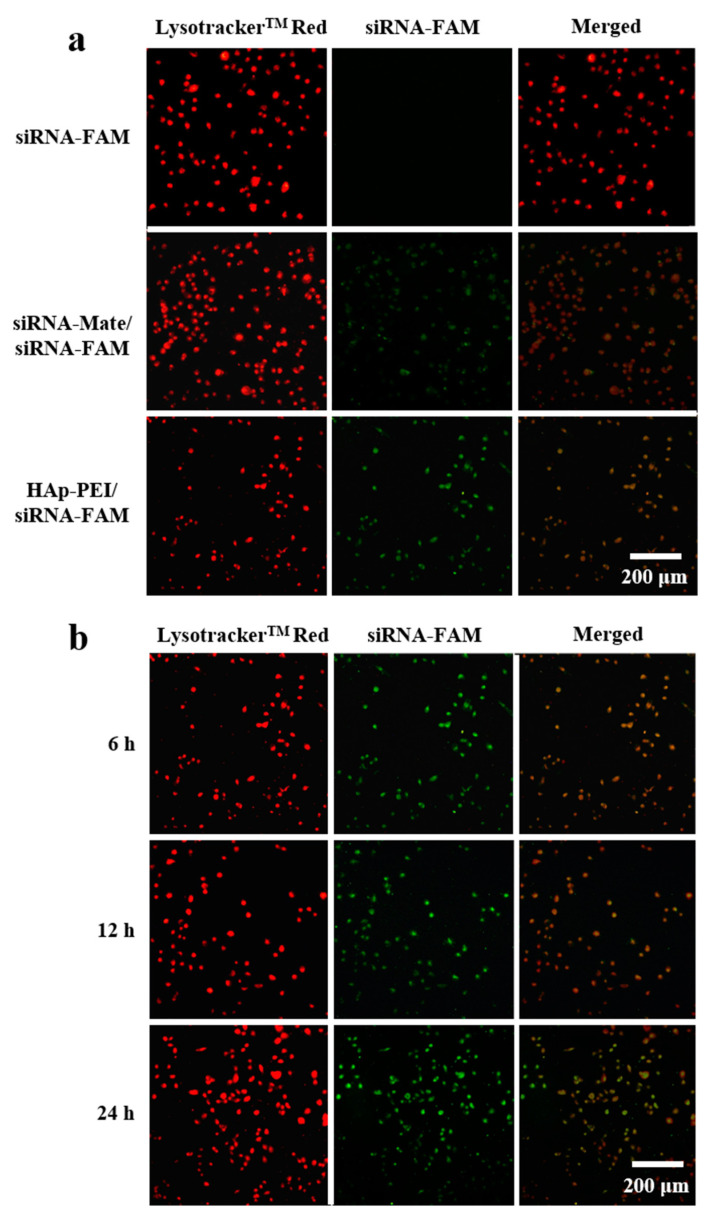

In vitro transfection is closely related to siRNA delivery efficiency [36]. In general, high transfection of siRNA leads to the high efficiency of gene silencing. In this study, a fluorescent microscope was used to observe the intracellular uptake of siRNA-FAM (green fluorescence) in PANC-1 cells. As shown in Figure 6a, free siRNA-FAM could not enter into cells due to its negative charge, demonstrating no green fluorescence. Compared with the transfection effect of commercial transfection reagent (siRNA-Mate), siRNA-FAM could be transfected effectively by HAp-PEI and showed no significant difference. Moreover, the green fluorescence (siRNA-FAM) and red fluorescence (lysosome, staining of LysotrackerTM Red) reached almost overlapping, indicating that HAp-PEI has successfully entered into the lysosome of cells after carrying siRNA-FAM, which provides strong support for the RNA interference in cancer cells. Significant visible fluorescence (Figure 6b) is observed after 6-h transfection and existed after 24 h. In addition, the intensity of the fluorescence in HAp-PEI/-siRNA-FAM treatment groups increased as the incubation time prolonged from 6 h to 24 h, suggesting the transfection of siRNA guided by HAp-PEI is effective and lasts for a very long time, which will facilitate siRNA-based gene silencing in cancer cells.

Figure 6.

The pancreatic cancer cell PANC-1 transfected siRNA-FAM (green fluorescence) by (a) siRNA-Mate and HAp-PEI for 8 h and (b) HAp-PEI for 6, 12, and 24 h. Cell lysosome was stained with LysotrackerTM Red (red fluorescence).

3.6. KRAS Gene Silencing Effect

KRAS gene mutation has a strong relationship with the incidence of PC, and various strategies have been developed to inhibit KRAS gene expression to counteract the growth of pancreatic cancer cells. Earlier researchers reported that many designed nanoparticles served in gene and siRNA delivery. Diverse methods such as covalent chemical bonding have been applied to modified nanoparticles to improve gene and siRNA transfection efficiency. However, the typical chemical approach requires tedious cross-linking procedures with organic chemical solutions, which may destruct the gene and siRNA feature, and affect gene therapy function. We have developed a biocompatible HAp-PEI nanoparticle as an efficient carrier to deliver KRAS-siRNA for anti-pancreatic cancer therapy by a simple and effective electrostatic interaction strategy. In this study, KRAS siRNA (siKras) was transferred into pancreatic cancer cells by HAp-PEI, and the HAp-PEI/siKras based gene-silencing effect was evaluated by RT-qPCR and Western blot assay.

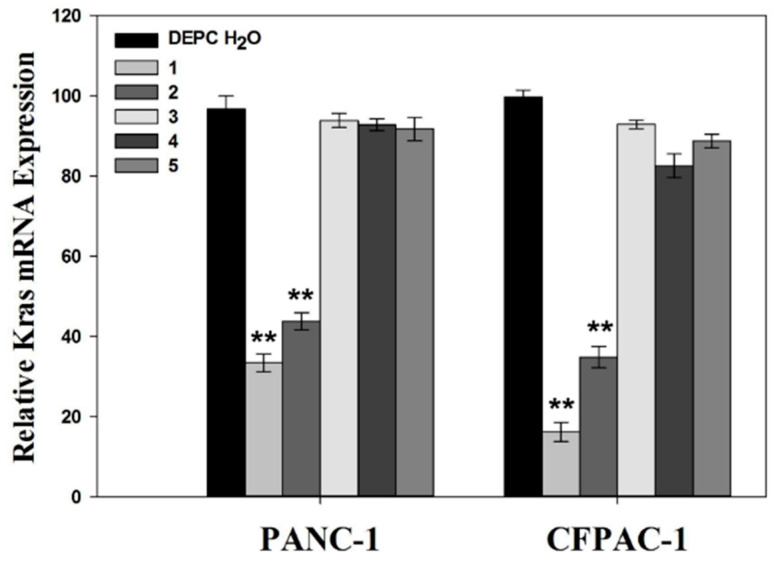

The prepared HAp-PEI was utilized to deliver siKras into PC cells (PANC-1 and CFPAC-1) and knock down the expression of the KRAS gene. After siKras transfection by HAp-PEI and siRNA-Mate for 48 h, the expression of Kras mRNA was evaluated by RT-qPCR. Figure 7 (1. siRNA-Mate/siKras, 2. HAp-PEI/siKras group) revealed that the expression of Kras mRNA is significantly downregulated in PANC-1 cells and CFPAC-1 cells (p < 0.01), while KRAS gene silencing failed in the DECP H2O and (3) siKras, (4) HAp-PEI, and (5) HAp/siKras groups. It is obvious that free siKras (3. siKras group) showed no significant effect of KARS gene silencing (p > 0.05), which is consistent with the fluorescence siRNA-FAM transfection result. As predicted, the (2) HAp-PEI/siKras group showed a stronger ability to silence the Kras mRNA expression compared with the (5) HAp/siKras group, indicating that the modification of PEI could greatly increase the siRNA transfection efficiency by pure HAp.

Figure 7.

Expression of Kras mRNA in PANC-1 and CFPAC-1 cells after treatment by (1) siRNA-Mate/siKras, (2) HAp-PEI/siKras, (3) siKras, (4) HAp-PEI, and (5) HAp/siKras for 48 h. DECP H2O was used as control. Values are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance relative to the group of control: ** p < 0.01.

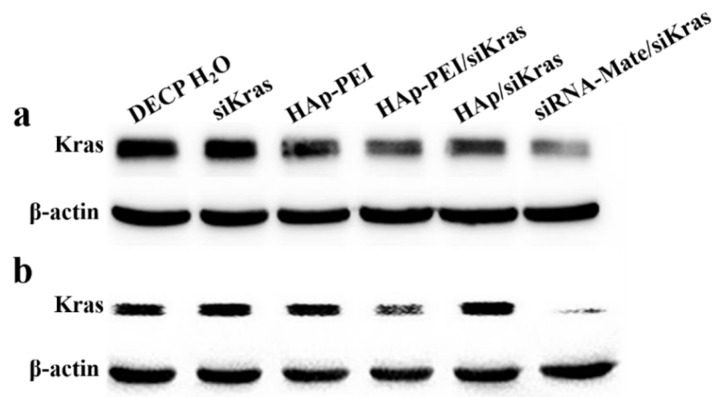

Next, the expression level of Kras protein in PANC-1 and CFPAC-1 cells was evaluated via Western blot assay after different treatments to clarify the gene silencing potency of HAp-PEI/siKras. As shown in Figure 8, compared with other groups, the siRNA-mate/siKras group and HAp-PEI/siKras group showed significant downregulation of the expression level of Kras protein. ImageJ software was used to have a relative quantitative analysis of Kras protein expression level. DECP H2O treatment was used as a control. As listed in Table 2, the decrease of Kras protein expression level in both PANC-1 and CFPAC-1 cells showed a trend with siRNA-mate/siKras > HAp-PEI/siKras > HAp/siKras, while other treatments, including free siKras, did not display significant influences, which is also consistent with the downregulation expression of Kras mRNA as shown in Figure 7. The results of both RT-qPCR and Western blot demonstrated that the HAp-PEI/siKras could significantly silence the expression of the KRAS gene. Therefore, HAp-PEI, as a powerful carrier, is promising for siRNA-based gene silencing in anti-pancreatic cancer.

Figure 8.

Expression of Kras protein in (a) PANC-1 and (b) CFPAC-1 cells after siKras transfection for 48 h by HAp-PEI, Hap, and siRNA-Mate. DECP H2O, siKras and HAp-PEI treatment were used as control.

Table 2.

Relative quantification of Kras protein expression.

| DEPC H2O | siKras | HAp-PEI | HAp-PEI/siKras | HAp/siKras | siRNA-Mate/siKras | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANC-1 | 100% | 97.65% | 96.46% | 51.52% | 74.13% | 22.22% |

| CFPAC-1 | 100% | 106.15% | 104.03% | 67.04% | 105.10% | 32.87% |

3.7. In Vitro Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Effect

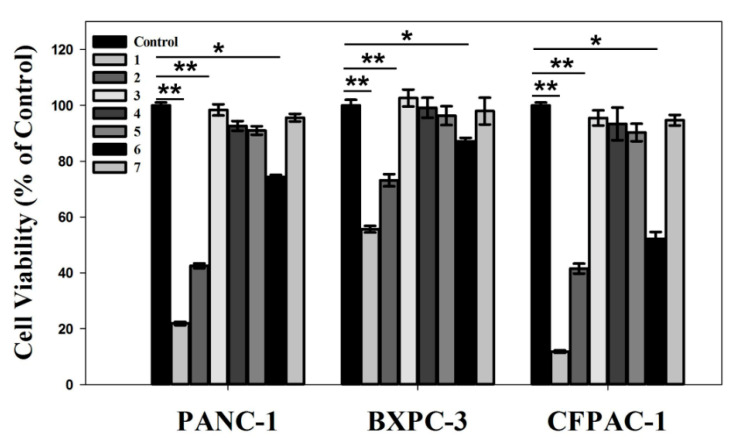

KRAS gene silencing through RNA interference can inhibit the growth of pancreatic cancer cells, which is promising for gene therapy of pancreatic adenocarcinoma disease. The prepared HAp-PEI/siKras in this study is proven to have an effective KRAS gene silencing effect (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Thus, we evaluated the in vitro anti-pancreatic cancer effect in PC cells (PANC-1, BXPC-3 and CFPAC-1) via MTT assay. Cells were treated with (1) siRNA-Mate/siKras, (2) HAp-PEI/siKras, (3) DEPC H2O, (4) siKras, (5) HAp-PEI, (6) HAp/siKras, and (7) siNC/HAp-PEI, respectively, for 72 h. Untreated cells served as the control groups. According to the MTT assay results, the cell viabilities in HAp-PEI/siKras-treated PANC-1, BXPC-3and CFPAC-1 cells were about 40%, 65%, and 40%, respectively, in comparison with the untreated cells, suggesting significantly high cytotoxicity of PC cells (Figure 9, p < 0.01). The HAp-PEI/siKras nanoparticles degraded quickly after going inside the lysosomes (pH 5.6) to release the siRNA and activated the siRNA-based gene silencing in cancer cells, which shows positive results in mRNA and protein expression level, and pancreatic cancer cells were killed. These results may confirm the stability of siRNA in different physiological conditions. Moreover, the cytotoxicity of HAp and HAp-PEI in the normal pancreatic cell HPDE6-C7 evaluated by MTT is shown in Figure 4, and the cell viability remained over 90%, indicating their low toxicity and side effects.

Figure 9.

In vitro anti-pancreatic cancer effect. PANC-1, BXPC-3, and CFPAC-1 cell viability after treatment by (1) siRNA-Mate/siKras, (2) HAp-PEI/siKras, (3) DEPC H2O, (4) siKras, (5) HAp-PEI, (6) HAp/siKras, and (7) HAp-PEI/siNC for 72 h. Untreated cells were used as control. Values are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance relative to the group of control: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we developed a biocompatible HAp-PEI nanoparticle as an efficient carrier to deliver KRAS-siRNA for anti-pancreatic cancer therapy. The active tumor-targeted HAp-PEI/siKras nanoparticle exhibited high siRNA transfection efficiency comparable to a commercial transfection reagent siRNA-Mate, effectively knocked down the expression of KRAS gene, and downregulated the expression of Kras protein in vitro. Meanwhile, HAp-PEI/siKras was able to inhibit the PC cells’ (PANC-1, BXPC-3 and CFPAC-1) proliferation. Moreover, no obvious in vitro cytotoxicity was observed of HAp-PEI-treated normal pancreatic cell HPDE6-C7, suggesting its good compatibility in such a gene delivery system. Finally, these studies provided a potential strategy of siRNA-targeted gene therapy for anti-pancreatic cancer therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L., X.X. and X.K.; methodology, D.L., X.X. and J.F.; software, D.L., X.X. and Q.Z. (Quan Zhang); validation, Q.Z. (Qingwei Zhao), R.Z. and Q.Z. (Quan Zhang); formal analysis, M.Z.I., P.Z. and J.F.; investigation, R.Z., X.X. and P.Z.; resources, Q.Z. (Qingwei Zhao) and P.Z.; data curation, D.L. and M.Z.I.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L. and M.Z.I.; writing—review and editing, D.L., M.Z.I. and J.F.; visualization, Q.Z. (Qingwei Zhao), R.Z. and Q.Z. (Quan Zhang); supervision, X.K.; project administration, X.K.; funding acquisition, X.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by Zhejiang Key Project for Science and Technology (2021C01180), Zhejiang International Science and Technology Cooperation Project (2019C04020) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51272236, 51672250).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mizrahi J.D., Surana R., Valle J.W., Shroff R.T. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2020;395:2008–2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30974-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawla P., Sunkara T., Gaduputi V. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: Global trends, etiology and risk factors. World J. Oncol. 2019;10:10–27. doi: 10.14740/wjon1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan X., Sivakumar S., Bednarsch J., Wiltberger G., Kather J.N., Niehues J., de Vos-Geelen J., Valkenburg-van Iersel L., Kintsler S., Roeth A. Nerve fibers in the tumor microenvironment in neurotropic cancer—pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2021;40:899–908. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01578-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bengtsson A., Andersson R., Ansari D. The actual 5-year survivors of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma based on real-world data. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16425. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73525-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuigan A., Kelly P., Turkington R.C., Jones C., Coleman H.G., McCain R.S. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4846–4861. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i43.4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strobel O., Neoptolemos J., Jäger D., Büchler M.W. Optimizing the outcomes of pancreatic cancer surgery. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019;16:11–26. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qadan M., Ma Y., Visser B.C., Kunz P.L., Fisher G.A., Norton J.A., Poultsides G.A. Reassessment of the current American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014;218:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haqq J., Howells L.M., Garcea G., Metcalfe M.S., Steward W.P., Dennison A.R. Pancreatic stellate cells and pancreas cancer: Current perspectives and future strategies. Eur. J. Cancer. 2014;50:2570–2582. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fuchs H.E., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biankin A.V., Waddell N., Kassahn K.S., Gingras M.-C., Muthuswamy L.B., Johns A.L., Miller D.K., Wilson P.J., Patch A.-M., Wu J., et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. 2012;491:399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Che Y., Siprashvili Z., Kovalski J.R., Jiang T., Wozniak G., Elcavage L., Khavar P.A. KRAS regulation by small non-coding RNAs and SNARE proteins. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5118. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13106-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deramaudt T., Rustgi A.K. Mutant KRAS in the initiation of pancreatic cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 2005;1756:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neoptolemos J.P., Kleeff J., Michl P., Costello E., Greenhalf W., Palmer D.H. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer: Current and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;15:333–348. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannon G.J. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bobbin M.L., Rossi J.J. RNA interference (RNAi)-based therapeutics: Delivering on the promise? Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016;56:103–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pecot C.V., Calin G.A., Coleman R.L., Lopez-Berestein G., Sood A.K. RNA interference in the clinic: Challenges and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreutzer J.N., Ruzzene M., Guerra B. Enhancing chemosensitivity to gemcitabine via RNA interference targeting the catalytic subunits of protein kinase CK2 in human pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:440. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J., Hu K., Guo J., Cheng F., Lv J., Jiang W., Lu W., Liu J., Pang X., Liu M. Suppression of KRas-mutant cancer through the combined inhibition of KRAS with PLK1 and ROCK. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11363. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan H.-T., Xue X.-H., Dai Z.-J., Wang X.-J., Li A., Qin Z.-Y. Down-regulation of survivin expression by small interfering RNA induces pancreatic cancer cell apoptosis and enhances its radiosensitivity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2901–2907. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i18.2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yonezawa S., Koide H., Asai T. Recent advances in siRNA delivery mediated by lipid-based nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020;154:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roma-Rodrigues C., Rivas-García L., Baptista P.V., Fernandes A.R. Gene therapy in cancer treatment: Why go nano? Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:233. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12030233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giger E.V., Castagner B., Räikkönen J., Mönkkönen J., Leroux J.C. siRNA transfection with calcium phosphate nanoparticles stabilized with PEGylated chelators. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2013;2:134–144. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang D., He B., Mi P. Calcium phosphate nanocarriers for drug delivery to tumors: Imaging, therapy and theranostics. Biomater. Sci. 2019;7:3942–3960. doi: 10.1039/C9BM00831D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ullah I., Gloria A., Zhang W., Ullah M.W., Wu B., Li W., Zhang X. Synthesis and characterization of sintered Sr/Fe-modified hydroxyapatite bioceramics for bone tissue engineering applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019;6:375–388. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo D., Ruan S., Liu A., Kong X., Lee I.S., Chen C. Laminin functionalized biomimetic apatite to regulate the adhesion and proliferation behaviors of neural stem cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018;13:6223–6233. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S176596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mushtaq A., Zhao R., Luo D., Dempsey E., Wang X., Iqbal M.Z., Kong X. Magnetic hydroxyapatite nanocomposites: The advances from synthesis to biomedical applications. Mater. Design. 2020;197:109269. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2020.109269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu Y.H., Yan X.B., Huang D., Han R., Wu L.X. NR2B-siRNA mediated by hydroxyapatite nanoparticles relieves for Malin-induced pain of mice. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012;343:926–932. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.343-344.926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu X., Li Z., Zhao X., Keen L., Kong X. Calcium phosphate nanoparticles-based systems for siRNA delivery. Regen. Biomater. 2016;3:187–195. doi: 10.1093/rb/rbw010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin R., Bao X., Wang H., Zhu S., Liu Z., Chen Q., Ai K., Shi B. TRPM2 promotes pancreatic cancer by PKC/MAPK pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:585. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei Y., Tang L., Xie Y., Xianyu Y., Zhang L., Wang P., Hamada Y., Jiang K., Zheng W., Jiang X. Gold nanoclusters-assisted delivery of NGF siRNA for effective treatment of pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15130. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu S., Shi J., Feng D., Yang L., Cao S. Hollow hierarchical hydroxyapatite/Au/polyelectrolyte hybrid microparticles for multi-responsive drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2014;2:6500–6507. doi: 10.1039/C4TB01066C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai W., Chen C., Ren X., Lee I.-S., Jiang G., Kong X. Hydrothermal fabrication of porous hollow hydroxyapatite microspheres for a drug delivery system. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. 2016;62:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson R.M., Dowker S.E., Elliott J.C. Rietveld refinements and spectroscopic structural studies of a Na-free carbonate apatite made by hydrolysis of monetite. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4682–4692. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng D., Shi J., Wang X., Zhang L., Cao S. Hollow hybrid hydroxyapatite microparticles with sustained and pH-responsive drug delivery properties. RSC Adv. 2013;3:24975–24982. doi: 10.1039/c3ra44609c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koutsopoulos S. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite crystals: A review study on the analytical methods. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002;62:600–612. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y., Malcolm D.W., Benoit D.S. Controlled and sustained delivery of siRNA/NPs from hydrogels expedites bone fracture healing. Biomaterials. 2017;139:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.